Impure means lead to an impure end.

A long, long time ago there lived a distant descendant of the gods. No one knows his original name, but the Greeks called him Jason. I’ll have to make do with this name since I don’t know any other. Now Jason was no ordinary man, for blue blood ran in his veins. His father was King Aison of Iolchos in Thessalia. But, as so often in mythology, Jason had a wicked stepbrother who deprived him of the throne when he was still an infant. Jason’s father arranged for his small offspring to be brought up by a centaur. Others say that it was his mother who took him to the centaur, but that is not the important thing here.1, 2 The centaurs were a curious cross-breed, with a man’s head and upper torso and arms, but the body of a horse. A truly astonishing phenomenon. And Jason must have had a rather unusual kind of upbringing!

Jason is connected with an oracle, for anyone who was anything in ancient Greece had something to do with an oracle. The prophecy in this case warned of a man with just one sandal. As the disreputable king, Jason’s stepbrother was one day holding a celebratory buffet on the beach, when a tall, beautiful young man came striding along. This was Jason, and he was wearing only one sandal because he had lost the other in the mud of a river. Jason was clothed in a leopard’s skin and a leather tunic. The king did not recognize the stranger and asked irritably who he was. Jason, smiling, answered that his foster-father the centaur called him Jason, but that his real name was Diomedes, and he was the son of King Aison.

Jason soon realized with whom he was talking, and quickly demanded the throne back, which was rightfully his. Surprisingly the king agreed, but on one condition—which, he assumed, could not be fulfilled. He said that Jason must free his kingdom from a curse, which had been laid both on him and on the whole country. He must fetch the Golden Fleece that was guarded by a dragon in a faraway place. This dragon never slept. Only when this deed had been accomplished would the king relinquish his kingdom.

Jason agreed, and thus began the most incredible science-fiction story. First, Jason went in search of an extraordinary shipbuilder, who would construct the most amazing ship of all time. This man was called Argos, and scholars disagree about where he came from. What is certain is that Argos must have been an outstanding engineer, for he built Jason a ship unlike any that had ever been seen before. Naturally, Argos had unusual connections, for none other than Athene herself gave him advice, and under her direction a vessel was built from a kind of wood which “never rots.”3Not content with that, Athene personally contributed an unusual sort of beam and built this in to the ship’s bows. It must have been an astonishing piece of wood, for it could speak. Even as the ship left the harbor, the beam shouted out in gladness because the journey was starting, and later it warned the ship’s company of many dangers. Argos, the shipbuilder, christened the mighty ship Argo, which in ancient Greek means roughly “fast” or “fleet-footed.”4 The ship’s company were thus called “Argonauts,” and the whole story is called the Argonautica. (Our astronauts and cosmonauts take their name indirectly from the Greek Argonauts.)

The Argo had room for 50 men, who must all have been specialists in various fields. That is why Jason had sent messages to every royal house in his search for a team of volunteers with particular abilities. And they came, all heroes and offspring of the gods. The list of the original crew is only partially preserved, and scholars say that other names were added by later authors.5, 6, 7 The crew must have been quite phenomenal, and it included the following people: Melampus, a son of Poseidon; Ancaeus of Tegeg, also a Poseidon offspring; Amphiarus the seer; Lynceus the look-out; Castor of Sparta, a wrestler; lphitus, the brother of the king of Mycenae; Augeias, the son of the king of Phorbas; Echion the herald, a son of Hermes; Euphemus of Tainaron, the swimmer; Heracles of Tiryns, the strongest man; Hylas, the beloved of Heracles; Idmon the Argive, a son of Apollo; Acastus, a son of King Pelias; Calais, the winged son of the Boreas; Nauplius, the sailor; Polydeuces, the prizefighter from Sparta; Phalerus, the archer; Phanus, the Cretan son of Dionysus; Argos, the builder of the Argo; and Jason himself, the leader of the enterprise.8, 9

The various authors who described the journey of the Argo more than 2,000 years ago added other names. At different points in Greek history, writers or historians concerned with the Argonauts assumed that this or that famous character must also have been there. The oldest list is in the Pythian Poem IV, recorded by a writer called Pindar (roughly 520–446 BC). This contains only ten names: Heracles, Castor, Polydeuces, Euphemnus, Periclymenus, Orpheus, Echion, and Eurytus (both sons of Hermes, the messenger of the gods), as well as Calais and Zetes. 10, 11 Pindar continually emphasizes that all these heroes were of divine descent.

The best and also most detailed description both of the whole journey and the heroes taking part in it, comes from Apollonius of Rhodes. He lived at some point between the 3rd and 4th centuries BC. Now Apollonius was certainly not the originator of the Argonautica. Various scholars assume that he must have drawn the basic story from much older sources.12, 13 Apollonius writes in his “First Song” that poets before him had told how Argos, guided by Pallas (Athene), had built the ship. Fragments of the Argonautica can be traced back as far as the 7th century BC. Scholars do not exclude the possibility that the story actually originated in ancient Egypt.

The Argonautica by Apollonius was translated into German in 1779. In quoting from the story, I will mainly draw upon this translation, now over 200 years old. The 1779 translation is not yet imbued with our modernist attitudes, and reflects Apollonius’ original flowery style. An excerpt from the list of names, written down roughly 2,400 years ago, goes as follows:

Polyphemus, the Elatid, came from Larissa. Long ago he had stood shoulder to shoulder with the Lapiths, fighting in battle against the wild centaurs…

Mopsus came too, the Titaresian, who had learned from Apollo to interpret the flight of birds…

Iphitus and Clytias were also of his party, the sons of wild Eurytus, to whom the god who shoots far had given the bow…

Alcon had sent his son, although no son now remained in his house…

Of the heroes who left Argos14 Idmon was the last. He learned from the god [Apollo] the art of watching the flight of birds, of prophecy and of reading the meaning of the fiery meteors…

Lynceus came also…his eyes were unbelievably sharp. If the rumor is true, he could see deep into the earth…

Afterwards came Euphemus from the walls of Tenaros, the most fleet of foot… two other sons of Neptune came too….15

Whichever list of names is closest to the original, the Argonauts were, at any rate, a hand-picked company of gods’ sons, each with his own astonishing gifts and special expertise. This extraordinary group gathered in the harbor of Pagasai on the Magnesia peninsula, to set off with Jason in his quest for the Golden Fleece.

Before the journey began, they held a feast in honor of Zeus, the father of the gods,16 and then the whole team marched on board, through a crowd of thousands of inquisitive observers. Apollonius describes it as follows:

Thus did the heroes pass through the town and make their way down to the ship…. With them and around them ran a great, foolish mob. The heroes shone like stars in the sky between the clouds…17

The people hailed the brave seafarers and wished them success in all their undertakings and a safe homecoming, while anxious mothers pressed their children to their breasts. The whole town was in uproar until the Argo finally sailed over the horizon and vanished from sight.

And why all this effort? Because of the Golden Fleece. But what is this slightly bizarre object of desire? Most encyclopedias I consulted describe the Golden Fleece as the “fleece of a golden ram.”18, 19, 20, 21 So this whole Argonaut crew is supposed to have set sail because of a fleece? The greatest ship of the time is supposed to have been built, and sons of gods and kings to have freely offered their services, in the quest of a ridiculous bit of fur? And a curse—one that needed such effort to combat—was supposed to hang over the country because of this? And a dragon, who “never sleeps,” was meant to guard this lousy fleece day and night. Surely not!

No, definitely not, for the Golden Fleece was a very particular skin with astonishing properties. It could fly!

The legend tells that Prixos, a son of King Athamas, had suffered a great deal because of his wicked stepmother, until his real mother snatched him and his sister away. She placed the children on the back of a winged golden ram, which the god Hermes had once given her, and on this miraculous beast the two flew through the air over land and sea, finally landing in Aia, the capital of Colchis. This was a kingdom at the farthest end of the Black Sea. The king of Colchis is described as a violent tyrant who easily broke his word when it suited him, and who wanted to hang on to this “flying ram.” The Golden Fleece was thus nailed firmly to a tree. In addition, the services of a fire-spitting dragon which never slept were enlisted to guard it.

So the Golden Fleece was some kind of flying machine that had once belonged to the god Hermes. It must on no account remain in the hands of a tyrant, who might have misused it for his foul purposes—hence the top-class crew with their various expertise, and the help of the gods’ descendants. They all wanted to regain what had been the property of the Olympians.

Hardly had they embarked when the Argonauts elected a leader in democratic manner. Heracles, the strongest of all men, was chosen, but he turned down the job. He declared that this honor belonged to Jason alone, the initiator of the whole expedition. The ship passed swiftly out of Pagasai harbor and rounded the peninsula of Magnesia.

After a few harmless adventures, the crew reached the Capidagi peninsula, which is connected to the mainland by a strip of land. There lived the Dolion people, whose young king Cyzicus asked the Argonauts to tie up in the harbor in the bay of Chytos—somehow forgetting to warn them about the giants with six arms who also lived there. The unsuspecting Argonauts climbed a nearby mountain to get their bearings.

Only Heracles and a few men remained to guard the Argo. The six-armed monsters immediately attacked the ship—unaware, however, of Heracles, who saw them coming and killed a few of them with his arrows before the battle even began. Meanwhile the other Argonauts returned, and thanks to their special talents, butchered the attackers. Apollonius writes of these giants: “Their body has three pairs of sinewy hands, like paws. The first pair hangs on their gnarled shoulders, the second and third pairs nestle at their horrible hips…”22

Giants? Nothing more than the fantasy of a story-teller? In our forefathers’ ancient literature, at least, such beings are not uncommon Any Bible reader will remember the fight between David and Goliath. And in Genesis it says: “There were giants in the earth in those days, and also after that, when the sons of God came in unto the daughters of men, and they bare children to them….”23

Other passages in the Bible which speak of giants are Deuteronomy 3:3-11; Joshua 12:4; 1 Chronicles 20:4-5; Samuel 2 1:16. And in the book of the prophet Enoch there is an extensive description of giants. In Chapter 14 one can read: “Why have you done as the children of earth and brought forth the Sons of giants?”24

In the Apocrypha of Baruch we even find numbers: “The Highest brought the flood upon the earth, and did away with all flesh and also the 4,090,000 giants.”25 This is confirmed in the Kebra Negest, the story about the Ethiopian kings:

Those daughters of Cain, however, with whom the angels had done indecent acts, became pregnant, but could not give birth, and died. And of those in their wombs, some died and others came out by splitting the bodies of their mothers…as they grew older and grew up these became giants.26

And in the books containing the “tales of the Jews in ancient times”27one can even read about the different races of these giants. There were the “Emites” or “Frightful Ones,” then the “Rephaites” or “Gargantuans”; there were the “Giborim” or the “Mighty Ones,” the “Samsunites” or the “Sly Ones”; and finally the “Avides” or “Wrong Ones” and the “Nefilim” or “Spoilers.” And the book of Eskimos is quite certain on this point: “In those days there lived giants on the earth.”28

I could carry on quoting such passages, but I would prefer not to repeat material from earlier books. Giants’ bones have also been found, although some anthropologists still try to insist that these are the bones of gorillas.29In 1936 the German anthropologist Larson Kohl discovered the bones of giant people on the shores of the Elyasi Lake in Central Africa. The German paleontologists Gustav von Königsberg and Franz Weidenreich were astonished to find several giants’ bones in Hong Kong chemists’ shops in 1941. The discovery was published and scientifically documented in the American Ethnological Society’s annual report of 1944.

About 3.5 miles (6 km) from Safita in Syria archaeologists dug up hand axes which could only have been used by people with giant hands. The stone tools which came to light in Ain Fritissa (East Morocco), measuring 12.5 × 8.5 inches (32 × 22 cm), must also have belonged to some hefty people. If they were able to wield such tools, which weigh up to 9.5 pounds (4.3kg), they must have been over 13 feet (4 m) tall. The discoveries of giants’ skeletons in Java, South China, and Transvaal (South Africa) are well known from specialist literature. Both Professor Weidenreich30 and Professor Saurat31 carefully documented their scientific research into giants. And the former French representative of the Prehistorical Society, Dr. Louis Burkhalter, wrote in the 1950 edition of the Revue du Musee de Beyrouth: “We want to make clear that the existence of giant people [in ancient times]…must be regarded as a scientifically certain fact.”

The Epic of Gilgamesh from Sumeria also tells of giants, as does, at the other end of the world, the Popol Vuh of the Mayans. The Nordic and Germanic myths, too, are peopled by giants. So why would the ancient world have so many stories about beings who never existed?

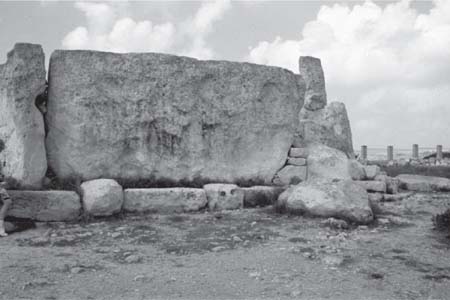

Image 1: The Gigantia temple on the Mediterranean island of Gozo is of unknown date.

Image 2: Who or what shifted this 69-foot-long stone? Giants? At the Gigantia temple on Gozo.

In the epic world of the Greeks, we hear about giants not only in the Argonautica but also in the later tale of Odysseus, who did battle with them. These powerfully-built figures are supposed to have been the fruit of a sexual union between men and gods. I have good reasons to believe that these same giants were responsible for the huge megalithic constructions which intrigue archaeologists, such as on the small islands of Malta and Gozo. The mighty ruins of a temple there still bear the name “Gigantia” (see Images 1 and 2).

The Argo continued its journey without any more major upsets, except that a sea-god called Glaucos shot up to the surface suddenly like a submarine from the depths. He brought the Argonauts a message from Zeus, for Heracles and his darling Hylas. Then Glaucos dived quickly under and sank down to the depths. Around him the waves frothed in many spiraling circles and poured over the ship.

In Salmydessos, the Argonauts encountered an old king who stank to high heaven, and was also starving. The poor fellow was called Phineus. He possessed the gift of prophecy, and had clearly divulged too many of the gods’ plans. The punishment they meted out to him was of a strange kind: whenever Phineus wanted to eat something, two winged creatures swooped down from the clouds and snatched the food away from him. Whatever they didn’t snatch they covered in filth so that it stank and was inedible. When the Argonauts arrived the old man hardly had the strength to move. He asked the Argonauts for help and promised to reward them by warning them of approaching dangers. Not of all dangers, though, for Phineus suspected that this was precisely what the gods didn’t want. The Argonauts felt sorry for him and prepared for themselves and the stinking king a luxurious feast. Just as the king was about to eat, the flying creatures—Harpies—swooped down from clear skies upon the food. But this time things turned out differently. Two of the Argonauts had the ability to fly, and pursued the fleeing Harpies into the air. The airborne Argonauts soon returned and told the king he now had nothing more to fear from the Harpies. They had been in hot pursuit behind them and would easily have been able to kill them—but the goddess Iris had commanded that they spare them, for they were the “dogs of Zeus.”

Just pure invention and fairy tale, one may be tempted to say. Someone rises up to the surface of the sea and makes the water spin, two Argonauts take off into the air with incredible speed, and Zeus, the father of the gods, possesses flying dogs. But this is only the modest beginning of a baffling science-fiction story from ancient times. Things get much more confusing!

The king, who by now smelled perfectly nice and was finally able to eat in peace, kept his promise and told the Argonauts of a few impending dangers. He described the route to Colchis which now lay before them, and warned particularly of two giant cliff walls which opened and shut like doors and crushed every vessel that did not get through at the right place and the right moment. The old king advised them to take a dove with them, and let it fly before them through the gap in the cliff walls. Apollonius says:

Now they steered into the foaming Bosphorus sound. The waves rose up like hills, threatening to collapse into the ship, often rising higher than the clouds. No one imagined that they would escape with their lives…but however terrible the waves, they become tame when a clever, experienced pilot has the tiller in his hand….32

The word “pilot” is not my invention. It appears in the 1779 translation of Apollonius. The king had described the route to the Argonauts down to the last detail; clearly he knew every bay and mountain, as well as the names of the countries and their rulers. Strangely enough, the king refers twice to the danger of the Amazons:

Further on you will come to the lands of Doan and the towns of the Amazons…. Do not for a moment think of coming ashore at a deserted place, where you will have trouble driving off the most unashamed birds who swoop around the island in great flocks. It is here that the rulers of the Amazons…have built their god a temple….33

The aging ruler even knows all about the Golden Fleece:

When you pass up-river through the estuary, you will have Aietes’ tower before you, and the shady grove of Mars, where the Fleece is…. It is guarded by a Lindworm, a terrible wonder. Neither day nor night does sleep press down its lids, never does he cease his constant watch….34

This lindworm, or dragon, reminds one of a kind of robot with a multitude of sensors. What kind of animal is it which has no bodily needs, never sleeps, and constantly watches everything around it? Similar creatures are described in other ancient texts, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, which was found in the hill of Kujundshik, the former Nineveh. The clay tablets on which it was written came from the library of the Assyrian king Assurpanipal. This epic describes how Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu climb up the mountain of the gods, on the top of which stood the shining white tower of the goddess Irnini. Just before they reach it, the fearful being Chumbaba approaches them. Chumbaba had paws like a lion, his body was covered in iron scales, his feet were armed with claws, horns shone upon his head, and his tail ended in a snake’s mouth. He must have been a frightful monster. The two companions shot arrows at him and threw spears, but all their missiles glanced off. From the mountain of the gods, bolts of lightning flared up: “a fire flamed up, it rained death. The brightness passed, the fire went out. All that had been struck by lightning turned to ash.”35

A little later Enkidu dies of an incurable illness. Terribly concerned, Gilgamesh asks: “Were you perhaps poisoned by the breath of the sky creature?” Whatever this “sky creature” was, it seems to have caused Enkidu’s death. During the further course of the story, “a door speaks like a person”! The speaking beam in the Argo does the same thing. And then there is the “Park of the Gods” that is guarded by two ugly mixed beings, gigantic “scorpion people.” Only their chests are visible above the earth, the rest of their bodies being anchored in the ground: “Horrible, frightful they look, and their gaze means death. The dreadful flashing of their eyes makes mountains roll down to the valleys.”36

Nevertheless, the scorpion people in the Epic of Gilgamesh have intelligence, more than can really be said of the lindworm and dragon guardians. Gilgamesh can talk with them, and they warn him of approaching dangers both on land and sea, just as King Phineus did to the Argonauts.

Phineus advises the Argonauts to take Euphemus with them on board. He was the one who let the dove fly between the two cliff walls, and who was also able to speed over water without getting his feet wet.

For 40 days the Argonauts relaxed in Phineus’ kingdom. (In the Epic of Gilgamesh, it takes 40 hours to reach the “Mountain of Cedars.”) A group of Argonauts slept on board the Argo, the others in the king’s palace. They restocked their provisions and set up an altar in honor of Jupiter. On the 41st day, the Argo set off down a winding river or canal. The Argonauts soon caught sight of the “swimming islands” with the dangerous cliff walls, and Euphemus sprang into action:

They steered slowly and with great care. Their ears were already deafened from afar by the crash of the rocks falling shut above. And loudly crashed back the echo of the wave-churning shores. Now Euphemus raised himself to the gable of the ship, holding the dove in his hand…. Yet they were afraid. Euphemus released the dove, they all raised their heads to watch it fly. But the cliff walls crashed together again from both sides, a deafening noise. From the sea great breakers of water sprayed upwards and the air hurtled around and around…the current dragged the ship backwards. The sharp rocks of the cliff just sheared off the dove’s outermost feathers, but she herself came through unharmed. The sailors cried aloud for joy…now the rock-walls tore far open again…since an unexpected wave rose up suddenly…when they saw it they were afraid it would swamp their vessel. But Tiphys eased them with a quick turn, so that the wave burst upon the good ship’s figure-head, then lifted it right up above the rocks, so that it floated gracefully there in the air…. Now the ship hung there like a hanging beam, but Minerva pressed her left hand against the rock and with her right gave the ship a push. Swift as a feathered arrow it flitted past the cliff…. This was meant to be, it was destiny.37

Tiphys, the Argo’s steersman, calmed his overwrought companions. Though they had escaped the terrible danger of the cliff walls, this miracle had only been possible with the help of the gods. Minerva had lent a helping hand, and the goddess Athene had given advice during the building of the ship, so that the Argo was “joined together by strong brackets and made unsinkable.”38

It was clear that the dangers could not have been overcome without divine aid. Now and then the Olympians also showed themselves. Shortly after their adventure with the crashing cliff walls, the Argonauts caught sight of the god Apollo flying over the Argo on his way from Lycia. This happened en route to the land of the Hyperboreans, which lay on the other side of the North Winds. Apollo was visiting “peoples of another race,” and the islands echoed to the sound of his flying boat. This once more shook the Argonauts to their core, so that they were moved to build him an altar. Soon after this Tiphys, the experienced pilot of the Argo, fell ill and died. His fellow voyagers raised a pyramid over his grave—astonishing really, as burial pyramids were not supposed to have appeared until the Egypt of the pharaohs.

During the following days, the Argonauts sailed around the “many bays on the cape of the Amazons.”39 A mighty river is described, unlike any other on earth, for a hundred other rivers are said to flow into it. Yet this river flows only from a single source, which comes down from the “Amazonian mountains.” The river, it is said, flows backward and forward through many provinces and (in Apollonius’ version):

No one knows for sure how many of its tributaries creep away through the land…. If the noble travellers had stayed longer on its banks, they would have had to do battle with the women, and blood would have been spilled, for the Amazons are swift and pay little heed to justice. They love war above all, and take pleasure in using force. They descend from Mars and Harmonia.40

The crew was not that keen on picking a fight with these Amazons, who ran down to the shore in full battle gear the moment they saw the Argo. The Argonauts had not forgotten the old King Phineus’ words, warning them of the Amazons. The old man had also spoken of “disaster in the sky,” and this followed a few days after they had left the bays of the Amazons.

As they landed on a lonely shore, the Argo was suddenly attacked by birds, which shot sharp and deadly arrows down on the Argonauts. The latter defended themselves by raising their shields over their heads, so forming one big protective barrier the length of the Argo. Other members of the crew began to utter a terrible noise which irritated the birds and sent them flying off.

The Argonauts went ashore. The whole region was dried up and there was no real reason for staying. Yet suddenly there appeared four stark-naked, emaciated figures, suffering from hunger and thirst, who only just had the strength to beg Jason for help. They said they were brothers, had been shipwrecked, and had clung on to bits of wreckage until being washed up on this island the night before. The Argonauts realized that these were the four sons of Prixos, who had once flown to Colchis with his sister on the Golden Fleece. They were a wonderful addition to the Argo’s crew, for they knew all about the grove where the Golden Fleece was held, and how to get there. One of the four sons of Prixos was called Argos, and it was he who, in the dead of night, guided the Argo to the Colchis coast, and from there to the mouth of the Phasis River. On its shore lay the town of Aia, with the king’s palace and—some way off—the grove where the Golden Fleece was.

What was the best way to proceed? Jason thought they could try the gentle approach first, and talk to the tyrant King Aietes who ruled the land of Colchis. The Argonauts knew that King Aietes was a violent ruler who did not keep his word, but on the other hand they had saved the lives of Prixos’ four sons, who were his nephews. The Argonauts built an altar and asked the gods for advice.

Some of the gods—the names are confusing and not important here—asked the young god of love Eros to arrange for the daughter of the tyrant, pretty Medeia, to fall hopelessly in love with Jason. This would lead her to help the Argonauts even against the will of her evil father. The goddess Hera joined in this “divine conspiracy” and shrouded the men who went to visit the palace in a kind of mist. This made the heroes invisible, so that they suddenly stood before the palace without having been noticed by soldiers and guards. The gods also made sure that Medeia would be the first person to catch sight of Jason. At the same moment Eros shot his arrow into the girl’s heart, so that she could not stop gazing at him.

What else could King Aietes do but welcome his uninvited guests? After all, they were bringing back his lost nephews, and his own daughter was asking him to arrange a meal with them. Jason tried to be diplomatic. He mentioned the fact that they were all related to each other through the race of gods, and that he had come to ask for the Golden Fleece.

King Aietes no doubt thought he had misheard. He had never for a moment dreamed of even putting the Golden Fleece on display, and now here was this young whippersnapper daring to ask for the greatest treasure of his kingdom. Aietes laughed aloud, and said, cunningly, that Jason could have the Golden Fleece if he passed three tests.

Outside the grove where the Golden Fleece was nailed, said sly Aietes, there were also caves where fire-spitting bulls lived. Jason must harness these bulls to a plough and till the field with them. Then he must sow dragon’s teeth in the furrows, which would quickly grow into frightful figures who must be fought and conquered. Jason would also have to deal with the fire-spitting dragon who never slept.

The shifty ruler knew very well that no one could do this. He did not think he was in the remotest danger of losing the Golden Fleece. However, he had reckoned without the “divine conspiracy.” After the evening feast Jason and his friends returned rather glumly to the Argo. They too thought the task was beyond them. Jason complained bitterly to his companions about the dreadful king’s conditions:

He says he has two untameable bulls on the field of Mars. Their feet are iron, they breathe flames. With these I must plough four acres of land. Then he wants to give me seed from the mouth of a dragon. From them, he says, armoured men will grow, whom I must kill before the day is done.41

But Jason’s new lover, the king’s daughter Medeia, knew how to help. She possessed a strange ointment with unusual effects. This miracle cure came from a medicinal herb that had grown from the blood of Prometheus the Titan. She told Jason to rub it all over his body and on his weapons. The ointment would protect him from heat and fire so that the fire-spitting bulls could not harm him. His weapons would also become invincibly strong, and give him superhuman powers.

Jason passed a quiet night, then washed himself thoroughly, made a sacrifice to the gods, smeared himself and his weapons all over with the miracle ointment, and pulled on his clothes. Soon after began the strangest battle described anywhere in ancient literature:

Suddenly, from the secret cavern, the locked stall, the whole air was full of acrid smoke. The two bulls shot forth, breathing fire from their nostrils. The heroes were seized with fright when they saw them. But Jason stood firm, his feet steady, and waited for their attack. He held his shield before him as they bellowed and at the same time struck him with their strong horns, but they were unable to move him even an inch from his position. As when the bellows in the blacksmith’s stove sets the fire fiercely roaring with a fearful rush and noise of heat, so the bulls blew flames from their mouths and bellowed at the same time. The heat engulfed the hero like a bolt of lightning, but the lady’s ointment protected him. And now he seizes the nearest bull by the point of its horns, and draws it by sheer force to the iron yoke. Then he trips up the iron foot with his own foot and floors the beast.42

As King Aietes had demanded, Jason ploughed the field with these unruly, fire-spitting animals, then threw the dragon’s teeth upon the furrows. Soon dreadful figures sprouted up everywhere on the battlefield, armed with metal spikes and shining helmets, and the soil beneath them shone white hot and lit up the night.

Jason took a mighty lump of stone, so large that even four men couldn’t have raised it, and threw it in the midst of the swelling ranks of monsters. They were confused and did not know where the attack was coming from. This gave Jason the chance to wreak havoc:

From the scabbard he drew the sword and with it stabbed whatever came his way. Many who were up to their navels in the ground still, and others who were still up to their shoulders. There were others, too, who had just got up on their feet, and then a whole crowd who had run into the battle too soon. They fought and fell…. Thus Jason mows them down…the blood ran in the furrows like streams of spring water…some fell on their faces and got mouthfuls of soil, others on their backs, others on their sides and arms. Of great girth they were, monstrous as whales.43

Jason made a clean sweep of them. But the worst was still to come: the dragon who never slept, who guarded the Golden Fleece. Together with his lover, Jason went to the grove where the Golden Fleece was fastened to a beech tree:

So they looked around for the shady beech and the Fleece upon it…it shone like a cloud that is illumined by the setting rays of the sun. But the Lindworm on the tree, who never sleeps, stretched out its long neck. It whistled in a horrible way. The hills and the deep grove rang with the sound…clouds of smoke filled the flaming wood, wave after wave of bright smoke snaked up out of the earth into the upper air, like the monster’s lengths of knotty tail, which were covered in hard scales.44

Jason could not see how to get around this monster, but once more his lover helped him. She smeared an elder branch with her special ointment and waved it around in front of the dragon’s glowing eyes. At the same time she spoke magic words, and the monster grew visibly slower and more soporific, until it finally laid its head upon the ground. Jason climbed the tree and released the Golden Fleece. The strange object glowed red, and was too large for Jason to carry on his shoulders. The ground below the Golden Fleece also shone the whole time that Jason was fleeing with it back to the Argo.

Once back on board, everyone wanted to touch the Golden Fleece, but Jason forbade this and covered it with a great blanket. There was no time for feasting or celebrations. Jason and the king’s daughter were afraid that King Aietes would do all in his power to get this unique treasure back. The Argonauts sailed as fast as they could down the river, and out to the open sea.

King Aietes, who had never meant to keep his word, ordered up a great fleet, which he divided so as to come at Jason and the Argonauts from both sides. Aietes’ ship reached a country whose inhabitants had never seen such travellers, and who therefore believed them to be sea monsters. (There is a similar story in the Ethiopian “Book of Kings,” the Kebra Negest, which tells how Baina-lehkem steals the greatest treasure of the time from his father Solomon: the Ark of the Covenant. Solomon sends his warriors to get it back. The chase is pursued—partly by flying machines—from Jerusalem to the [modem-day] town of Axum in Ethiopia.)

After a few minor adventures, which are described differently in various versions of the Argonautica, the Argo reached the “amber islands.” The talking beam in the prow of the ship warned the crew of the wrath of Zeus. (In the meantime the ship’s keel began to talk with audible voice.) The father of the gods was furious, for Jason had managed to kill the brother of his beloved. This did not occur through jealousy, but because Medeia had spun an intrigue. Later on in the story Jason was absolved of this murder, and Zeus was satisfied. On various islands and in many different lands the Argonauts raised altars and memorials. At some point the Argo ran far up into the rivers of Eridian. Astonished, one learns that “This is where Phaethon fell from the sun chariot down into the deepest sea when Jove’s flaming thunderbolt half burned him. This sea still stinks of sulphur…no bird spreads its wings and flies over it.”45

This is a strange reference. The story of Phaethon and his sun chariot is very ancient, and has not been precisely dated. The Roman poet Ovid gives it in full in his Metamorphoses, though Ovid lived about 40 years before Christ, at a time when the Argonautica has already existed for centuries. According to this tale, Phaethon was a son of the sun god Helios. One day Phaethon visited his father in the sky and asked him to fulfill one wish, because the earth-dwellers did not believe that he was really related to the sun god. He asked to be allowed to drive the sun chariot. His father was horrified and continually warned his offspring to give up the idea, telling him that to drive the sun chariot required quite particular knowledge. Typically, Phaethon didn’t want to heed these warnings. His father had unwittingly promised to fulfill his every wish, and so couldn’t get out of it now. The fiery horses were therefore refueled with four-star ambrosia, and harnessed up to the wagon.46

The sun chariot raced out into the sky, but the horses soon noticed that their driver couldn’t control them. They broke out of their usual course, rose high up into the sky then sped at dizzying speed down toward the earth again. This went on for a while—up, down, and all over the place—until the sun chariot started to get closer and closer to the earth. The clouds started steaming and whole forests and stretches of land caught fire. But the air in the heavenly vehicle also got hotter and hotter so that Phaethon could hardly breathe. As the fire engulfed his hair and skin, there was nothing left for him to do but leap out of the chariot, and his body was said to have fallen into the Eridanos River. His sisters, the Heliades, went there and wept so long that their tears turned to amber, which one still finds on the river’s banks. The heavenly chariot crashed with a shower of sparks into a lake.

Nowadays the tale of Phaethon is seen as a double parable. On the one hand is the sun which has the power to burn up whole stretches of land, on the other the young man who thinks that he can do anything his father can. I doubt whether this story was originally regarded by those who told it simply as a parable. Too many of its elements are too logical and show parallels with modern space travel technology. But this is equally true of other parts of the Argonautica.

After all, it is not just a matter of course if amphibious vehicles turn up in a tale that is millennia old. Apollonius tells us, “Out of the sea leapt a horse of unusual size, and came ashore. Its mane was golden, its head was high, and it shook off the salty foam from its sides. Then it ran off on feet as swift as the wind.”47

This amphibious horse is meant to have been one of Poseidon’s horses. Poseidon was the god of the sea, but also the god of Atlantis. We’ll come to that story later on. So what was going on here? Is Poseidon’s horse an isolated episode, something that only the Argonauts saw? Far from it.

In the Bible, in the book of the Prophet Jonah (Chapter 2), we can read the episode in which Jonah survived for three days and nights in the belly of a whale. Theologians say that this is meant prophetically, in reference to the three days from Jesus’ death to His resurrection. An absurd ideal. One learns more in Volume III of the book Die Sagen der Juden (“Tales of the Jews From Ancient Times”). Here we read that Jonah entered the jaws of the fish just as “a man enters a room.” It must have been a strange fish because its eyes were like “windows, and also shone inwards.” Of course, Jonah was able to speak with the fish, and through its eyes—portholes!—he could see, “bathed in light, as in the midday sun,” all that was happening in the sea and on the ocean floor.48

There is a parallel to this prehistoric submarine in the Babylonian Oannes Tale. Around 350 BC, a Babylonian priest wrote three works. He was called Berossus and served his god Marduk (also called Bel or Baal). The first volume of his book, the Babylonic, deals with the creation of the world and the starry firmament, the second volume with the Babylonian kingdom, and the third was a proper history. Berossus’ books are only preserved in fragments, but other ancient historians quote from them, such as the Roman Seneca, or Flavius Jospehus, a contemporary of Jesus. And in the 1st century after Christ, Alexander Polyhistor of Milet wrote about the Babylonians. Thus bits and pieces of Berossus’ work have survived the millennia.

This Babylonian priest also described a curious being, Oannes, that came out of the Eryteian Sea beside Babylon. This creature, he said, had the shape of a fish, but with a human head, human feet, and a tail, and had spoken like a human being. During the day Oannes had conversed with people, without eating anything. He had taught them not only knowledge of written signs and sciences, but also how to build towns and erect temples, how to introduce laws and measure the land, and everything else they might need to know. Since this time, no one had invented anything which exceeded his teaching. Before departing, Oannes had given the people a book containing his instructions.

Not bad for a teacher from the water. Of course, one can dismiss the Oannes tale as fantasy, as with every incredible story, but Oannes also forms part of the traditional tales of other ancient peoples. The Parsees call the teacher from the water “Yma,”49 the Phoenicians call it “Taut,” and there is even a monster with the body of a horse and the head of a dragon who rises up out of the depths of the ocean at the time of the Chinese emperor Fuk-Hi. This must have been a strange creature indeed, for its body was adorned with written signs.50

The amphibious horse in the Argonautica also turned out to be a speaking creature. The heroes and their vessel had come to a lake which had no opening to the sea. The team kept going by towing the Argo over land—probably with the help of wooden rollers. Finally they made an offering to the gods of a tripod which Jason was supposed to have received in Delphi, and straight away the amphibious creature reappeared. It was apparently called Eurypylus, another son of Poseidon. Eurypylus first appeared in the form of a beautiful and friendly youth, with whom one could have excellent conversations. He wished the Argonauts good luck on their further travels, showed them which way the sea was, and walked off with the tripod into the cold water. Then he grasped hold of the Argo’s keel and pushed the ship off into the current:

The god took pleasure in the worship afforded him, rose out of the depths and appeared in the shape of body natural to him. As a man will lead a horse into the swiftest course…he took hold of the Argo’s keel and led it gently into the sea…. But his lower body was divided into two separate fish tails. He beat the water with the pointed ends, which appeared crescent-shaped like the horns of the moon, and led the Argo until they came to the open sea. Then he suddenly vanished down into the depths. The heroes raised a loud shout when they saw this wonder.51

The “shout” of the Argonauts was quite understandable. When earthly forces don’t help, super-earthly ones have to. Jason’s friends carried on sailing and rowing for home, passing many countries on their way. On the heights of Crete they wanted to replenish their stocks of water, but this was prevented by Talos, who was endowed with an invulnerable, metal body. He is described as a “bronze giant,”52 or as a being whose “whole body was covered in bronze.”53 According to Apollonius, Talos encircled the island three times in a year, but all other ancient authors speak of “three times a day.”54 With his magic eyes he caught sight of every vessel which approached Crete, then pelted it from a great distance, apparently with rocks, with great accuracy. He also had the ability to radiate heat, drawing boats toward him and letting them go up in flames. Talos was said to have been made by the god Hephaestus, who was a son of Zeus. The Romans worshipped him as the god of fire, and named him Vulcanus. For the Greeks Hephaestus was both god of fire and protector of blacksmiths.

Zeus was said to have given Talos to his former beloved Europa, who once lived with this father of the gods on Crete. The reason they had gone there is shrouded in mythology. The Greeks assumed that Europa was the daughter of King Tyrros. When she was a girl, and playing with her animals, Zeus had come by and fallen for her. Zeus changed himself into a young and handsome bull, and Europa had gently got up on his back. This bull must have been another kind of amphibious machine, for hardly had Europa taken her seat than it plunged into the sea and swam with its lovely cargo to Crete. There, I assume, it turned back into a man, who made love to Europa. But gods are not constant in love; divine business required Zeus to leave Crete, and he gave Talos to his beloved, to guard the island from undesired visitors.

Although Talos was invulnerable, he did have a weak spot. On his ankle was a sinew covered in tanned skin, and under it lay a bronze nail or a golden screw. If this bolt was opened, then colorless—other writers say white or festering—blood poured out, and Talos would be incapacitated.

Jason and his Argonauts tried to approach Crete, but Talos spied the Argo and began to fire upon it. Once more it was Medeia, by now Jason’s wife, who suggested rowing out of range. She said that she knew a magic way of putting Talos out of action. Apollonius tells us:

They would gladly have sailed to Crete, but Talos, the steel man, prevented the noble ones tying up on shore with the dew still on their mast. For he hurled stones at them. Talos was one of the iron race of the earthly ones… a half god, a half man. Jupiter gave him to Europa to defend the island. Three times in each year he circled Crete with feet of iron. Ironclad and invincible was his body, but he had a vein of blood on the ball of his foot under the ankle, lightly covered by skin. This is where death lurked close to his life.55

The Argonauts quickly rowed away from the bombardment and out to the open sea. Medeia began to recite magic spells and to call upon the spirits of the abyss, which, once they have been called up, split the air. Then she cast a spell on Talos’ eyes so that imaginary pictures filled his gaze. Irritated, Talos knocked the sensitive place on his ankle against a cliff, and blood flowed out of the wound like molten lead:

Although he was made of iron, he succumbed to the magic…so he knocked his ankle against a sharp stone, and a sap like molten lead flowed out of him. He could no longer stand upright and fell over, just as a pine tree falls from the summit of a mountain…. Then he picked himself up again and stood upon his huge feet—but not for long for he fell to the ground again with a mighty crash.56

Talos tumbled helplessly back and forth, trying to right himself, but then lost his balance altogether and plunged with a horrific noise into the sea.

Now the Argo came to Crete’s shores and could anchor safely. But the Argonauts were longing for home by now, and after all they had a trophy to show—the Golden Fleece. After a short sojourn on Crete they headed off again to sea, and suddenly everything around them became dark. No star was visible any longer, and they seemed to be in some sort of underworld. The air was black as pitch—no spark of light, and no glint of moon. Jason begged Apollo not to leave them now, so near to their destination; he promised to offer many gifts in the temples of their homeland. Apollo shot down from the sky and lit up the whole surroundings with bright arrows. In their light the Argonauts caught sight of a small island, close to which they anchored. They set up a holy place in honor of Apollo, and called the islet Anaphe.

The rest of the story is quickly told.

The Argo sailed past several Greek islands and reached the harbor of Pagasai, where their journey had begun, without further problem. Jason and his crew were given a heroes’ welcome. Then follow a few family intrigues. Jason is said to have turned his attentions to another young lady, behavior which his wife Medeia frowned upon. She poisoned her children, put a curse on Jason’s girlfriend, and the poor fellow threw himself on his sword in desperation. So our divine hero ends the story rather unfittingly with suicide.

And what happened with the Golden Fleece? Below what castle or fortress does the skin of the flying ram lie buried? Who used it? Did it reappear again? In which museum can one admire it? The greatest voyage of ancient times took place because of the Golden Fleece. The thing must have been of enormous value to its new owner. But there is nothing more to be found in ancient literature; the trail of the Golden Fleece disappears in the mists of time.

Many authors and brilliant historians have told tales of the Argonauts, and the historians and exegetes of today have tried to understand the journey of the Argo. Where did the ship go? Where did the adventures take place? On which coasts, on which islands and mountains might one find the many altars and memorials which the Argonauts raised? Apollonius often gives us very precise geographical locations in his Argonautica, with many accompanying descriptions. My emphases in the following examples show how detailed Apollonius’ account is, and how seriously he takes his geography:

At Pytho, in the fields of Ortigern…they sailed with the wind behind them past the outermost horn, the Capes Tisae…behind them vanished the dark land of the Pelasges.

From there they sailed to Meliboa, and saw the wild waves breaking upon its rocky coast. And with the new day saw Homola which is built beside the sea. They left it behind them, and also soon passed the river mouth leading from the water of Amyrus. Then they caught sight of the plains of Eurymenas, and the deep folds of Olympus. Also Canastra…. In the twilight of evening, they glimpsed the peak of Mount Atho, whose shadow covers the island of Lemnos.

Until they came once more to the coasts of the Dolions…where they saw the Macriades rocks, and in front of them the land of Thrace. Also the airy mouth of the Bosphorus, the hill of Mysen, and in the other direction the Aesaps and Nepeia River.

To the welcome mouth of the Calichor river. It was here that Bacchus once celebrated his orgies, when the hero returned to Thebes from the peoples of India.

Then they came to the land of Assyria…the early rays of dawn caressed the snowy peaks of the Caucasus.

In those days the Deucalides ruled the land of the Pelasges. But Egypt, the mother of the oldest race of men, was already growing in notoriety and fame…

They sailed further and dawn found them in the Land of the Hyllers. A large number of islands lay before them, and it is dangerous for ships to pass through them.

Iris descended from Olympus, ploughing through the air with outstretched wings, and alighting at the Aegean Sea.

Here rose Scylla from the waters…there roared Charybdis.57

These are only a few examples, which show that Apollonius knew very well in what part of the world the heroes of the Argo were conducting their adventures. Not only rivers, islands or specific regions are mentioned, but also seas or mountain ranges like the Caucasus. Ought it not to be very easy to plot the Argonauts’ journey?

Of course, this has been done—with very variable results. The two French professors Emile Delage and Francis Vian drew up clear maps,58, 59according to which Jason and his crew journeyed from the Caucasus at the eastern end of the Black Sea along the river Istros (the Danube) to the Adriatic, passing other tributaries on their way. In the Fo valley there were many small and larger rivers, which the Argonauts somehow managed to use to sail round the Alps, and to reach the Rhine and the Rhōne. In the region of present-day Marseilles they arrived at the Mediterranean again, and passed through the straits of Messina—the supposed Scylla and Charybdis. Finally they turned east in the direction of the (present) Ionian islands, then turned south and headed straight for the Great Syrtis of Libya. From there they sailed home via Crete. And where is the place where Phaethoe’s heavenly chariot crashed to earth? Not far from the western edge of Switzerland, in the Marais de Phaýton (Marsh of Phaethon)!

Reinhold and Stephanie Glei60, 61 provided still more exact maps. But I have problems with these; how does one get from the river Istros or Danube to the Adriatic, and from there via the Eridanos River in the Po valley to the “Celtic seas” of present-day France? After all, the Argo was not some rubber dinghy, but the greatest vessel of the age, with a crew of 50. It cannot be denied that there may have been waterways in those days which no longer exist—which would once more throw up the question of the date of the original Argonautica. At which geological epochs did navigable waterways exist where now there is only dry land?

A consul general of France, Monsieur R. Roux, compares the wanderings of Odysseus, described in great detail by the Greek poet Homer, with the Argonautica: “One must never forget the great precision and differentiation of Strabo: the Odyssey takes place in the western ocean, the Argosy in the eastern.”62

Christine Pellech has a quite different view. Her very thorough study also compares Odysseus’ wanderings with the Argonautica, concluding that “the Odyssey partly overlaps with the journey of the Argonauts.” She says that Odysseus actually sailed right round the world—millennia before Columbus—and puts forward the view that the Egyptians had drawn on Phoenician sources, and it was this “Phoenician-Egyptian mixture that was taken over wholesale by the Greeks.” The content of both the Argonautica and the Odyssey derives from Egypt, according to Pellech, and she substantiates this by the fact that Apollonius of Rhodes grew up in Alexandria, visited the library there, and only left Egypt after falling out with his teacher.63

Christine Pellech’s arguments read like well-documented research, and she also succeeds in identifying many points on the journey with actual places on the globe. Many questions still remain, however.

If what she says is true, then most of the geographical indications given by Apollonius must be wrong, and many scholars would have been wasting their time. What could the explanation be? Let us assume that Apollonius really brought the core of the Argonaut story from Egypt to Greece. Then, to conjure up a fuller picture for himself, he might well have adorned it with geographical details from his own experience. To do this, though, he would have to have had an extensive knowledge of the wide realms of the Greek world in those days, and also many rivers, coasts, and mountains beyond Greece. But even then we are left with difficulties; how, for instance, can one explain passages by Apollonius such as the following:

In the evening they came ashore on the Atlantides Island. Orpheus begged them not to spurn the solemnities of the island, nor the secrets, the laws, customs, the religious rites and works. If they observed these they would be assured of the love of heaven on their further voyage over the dangerous ocean. But to speak further of these things I do not dare.64

Let’s not forget that Atlantis was the island of the god Poseidon, that two of Poseidon’s sons were said to have travelled on the Argo, and that the amphibious vehicles which had surfaced from the sea had been the work of Poseidon. But how does Apollonius know about Atlantis—if that is what the word “Atlantides” refers to? He writes at least of solemnities which one should not spurn, but also of secrets, laws, and customs. And, though everywhere else he gives each little geographic detail, he now refrains from saying anything further about such things. Something doesn’t quite fit here, and I will return to the Atlantis story later.

Did the Argo journey ever actually take place? As long as we have no older sources to draw on than the ones cited here, we will probably never know. But I have been chasing the trail of the gods for the past 40 years, convinced that many elements of the Argonautica cannot have simply been invented. Imagination is a fine thing, and even millennia ago people enjoyed their flights of fancy. But fantasy is always based on something; it takes its starting point from events which once occurred, from circumstances which cannot be understood, from riddles which our reason cannot neatly pigeon-hole. Nowadays we try hard to put a psychological slant on the “imagination” of the ancients, using the old, worn-out schema of natural phenomena such as lightning and thunder, stars, silence and infinity, volcanic eruptions and earthquakes. But as the history of exegesis or commentary demonstrates, every scholar just thinks in terms of his own experience, conditioned by the time in which he lives. Our so-called “zeitgeist” narrows our perspective and dictates what is “reasonable” or “scientific.” My diligent secretary hauled 92 books on the Argonautica theme from Bern University library to my study. As usual, one nearly drowns in the miles of commentary written by high-powered academics at different periods—but no one really knows the truth. And every one puts forward a different argument.

I still stand by my basic conviction—on which I have elaborated in 32 books since 1968. All that I try to do is relate new arguments to my original theory, in the process of which the gaps in the mosaic get smaller and smaller, and the overall picture becomes increasingly more convincing. However, I admit that my theory has its blemishes, and that some of what I propose could be explained differently. But at the end of the day, what is the truth? Are the analyses by commentators in the past 100 years correct? Their conclusions convincing? Do they provide—as the scientific community simply assumes—a proven body of knowledge? Or is what they view as scientifically sound just an interpretation dictated by contemporary perspectives?

Here of course I lay myself right open to attack. What, people will say, is Erich von Däniken doing other than interpreting things from his contemporary perspective? That is true. But shouldn’t we have learned by now that we are only one living speck of dust in the depths of the universe? That the world and the cosmos are far more fantastic than our school learning tells us. Isn’t it time that, given the wealth of material, we admit that something is not quite right with our view of the early history of mankind? And that received views are wrong because they sweep thousands of pointers and hints under the carpet, and refuse even to contemplate them? I do have one advantage over the commentators: I know their arguments, but they don’t (care to) know mine.

New readers need to hear my old theories briefly. Sometime or other, many millennia ago, an alien crew landed upon earth. Our forefathers didn’t have a clue what was going on; they didn’t know anything about technology, let alone space travel. Their simple minds must have regarded the aliens as “gods”—although we all know that there aren’t any gods. The aliens first studied small groups and tribes of human beings, just as ethnologists do today. Here and there they gave advice for creating an ordered civilization. There was no language problem between people and “gods,” both because our civilization has always managed to pick up totally foreign languages, and because the first Homo sapiens sapiens probably learned their language from the “gods” in the first place.

Finally a rift and even mutiny occurred amongst the aliens. They broke the laws of their world of origin and their space commanders, and had sex with pretty daughters of men. Mutants resulted from these unions: huge monsters, the Titans of olden times. Another group of ETs undertook genetic engineering, and created mutants of all kinds. It must have been a real Frankenstein horror scenario. Then the mother spaceship departed with the “good” aliens, back into the depths of the cosmos—though not without having first promised to return at some point in the future.

The “gods” remaining behind on the earth squabbled amongst themselves. They still had bits and pieces of their original technology, and doubtless retained their original knowledge. They knew, for instance, how to work iron, make alloys, create dreadful weapons or robots. But they also knew how to make a hot-air balloon fly, or charge up a sun-powered battery. These “gods” produced children and naturally taught their offspring some of their technological knowledge.

These offspring spread over the earth, inhabiting different regions, which were ruled over in each case either by a single ruler or a family dynasty. They misused their subjects, the human beings, as work-horses, as food-producers, as serviceable idiots. But they also taught them a good deal, and set up the best of them as administrators, so-called kings.

The “gods” basically watched their subjects jealously: “Thou shalt have no other gods before me” was one of their laws. And when it came to battles and blows, the “gods” often supported their subjects with terrible weapons. The sons of the gods and their descendants from third and fourth generations often did battle with another.

So that is my theory, which I backed up from so many sources that the cross references alone turned into a whole book,65 and all my books together grew not only into an encyclopedia,66 but also into a CD-ROM. 67, 68 Not to mention the hundreds of books which other authors across the globe have published on the same theme. It is therefore quite natural that I am familiar with all the counter-arguments imaginable, and that I have long since dealt with them to my satisfaction.

What can the Argonautica have to do with extraterrestrials? What are the constituent elements which can hardly have just leapt out of the imagination of a group of people who lived X millennia ago? And let me be quite clear on this point: we’re not talking about the imagination of some Apollonius, or any other Greek poet, who wrote down their accounts 2,500 years ago. No, the core of the Argonautica story comes from a time about which we have no historical records—and this is simply because all the really ancient libraries were destroyed. Unless, of course, some unexpected treasure chamber is about to be opened in Egypt.

So what is it about the Argonautica which makes us sit up and take notice?

1. Quite a few of the voyagers are offspring of the gods, from the third and fourth generation. They possess superhuman characteristics.

2. “Mixed beings” are described, such as centaurs, giants with six arms, or the “winged dogs” of Zeus.

3. A goddess makes the Argo unsinkable.

4. The same goddess furnishes the ship with a “speaking beam.” This talkative piece of wood must have some hotline to someone, for it warns of approaching dangers.

5. A being called Glaucus surfaces from the waves like a submarine, and brings a message from one of the gods.

6. Cliff walls open and shut as in the tale of Ali Baba and the 40 thieves (“open sesame”).

7. King Phineus knows all about the dangers which will be encountered along the route. How?

8. Aietes’ tower near the town of Aia.

9. A god (Apollo) flies with noise and commotion over the ship. He is on the way to the land of the “Hyperboreans,” and visits “people of another race.”

10. Birds shoot deadly arrows, but are irritated by noise.

11. A goddess uses “mist” to make the men invisible.

12. An ointment gives superhuman powers and creates a heat-resistant shield.

13. A dragon which never sleeps, observes everything, has no physical needs, can spit fire, and never dies.

14. Fire-spitting bulls with metal legs.

15. A vehicle of the gods, which needs great experience to drive and control. As it crashes it sets fire to whole stretches of land, and the “pilot” must get out because of the unbearable heat inside it.

16. Various talking amphibious beings.

17. A god who lights up the night by means of “arrows of light.”

18. A metallic robot who circles an island. His eyes see ships coming, and he hurls missiles, bums up assailants, and has blood like molten lead.

19. A woman from the race of gods who manages to confuse this robot with “dream images.”

Even if we assume that the whole thing is just a tall tale engendered in the head of a dreamer, and later expanded and added to by poets of each succeeding age, does this mean that all questions must fall silent? Is there then no mystery to solve?

Even a tall tale has content. Its original inventor would have had to tell at least a halfway feasible story, for things have to have some cohesion and sense. The basic framework of the story is simple: One or several people set off to seek a unique and extremely valuable object. This object is guarded by an incomprehensible monster, and this all has something to do with the gods.

It doesn’t matter much whether the poet also puts in a love story somewhere, which ends happily. But where does the metal monster come from, which attacks ships, shoots things down, radiates heat, and had lead for blood? And where on earth did they get the idea of the fire-spitting dragon? Such creatures never existed in the whole evolution of this planet. No one could have just dreamed it up. There are therefore neither “archetypal” explanations, nor any dim, ancient “memories” at work here. And why does this race of dragons appear time and again in the tales of ancient peoples? The oldest Chinese stories tell of the dragon kings who descended from heaven to earth at the dawn of time. These are no products of fantasy or silly tales, for the dragon kings founded the first Chinese dynasty. No human weapon was able to harm them, and with their fire-spitting dragons they ruled the skies. The dragon kings’ flying machines made a terrible noise, and the founder of the first dynasty bore the name “Son of the Red Dragon.”69

None of this is mythology for, after all, the motif of the fire-spitting dragon influenced all of Chinese art for thousands of years, right up to our own times. And whoever still complains that such things cannot have been true, and that the dragon must be understood in psychological terms, should perhaps take a trip to Beijing and take a look at the great Red Square. What can be seen all along one side of it? The temple of the heavenly emperor!

Doesn’t it gradually occur to you that something is odd here? That all the accounts from antiquity are not just legends, myths, or imaginary fairy-tales, but a former reality? This far-off reality, however, can be proven in another way too: by following the trail of time itself.