Chapter 5

The Changing of the Guard

1960–1969

Prelude

In many ways the decade of the 1960s was one of the twentieth century’s most turbulent, a time that began with the optimistic ascendancy of John F. Kennedy to the White House and ended with the horrifying reality of Vietnam. In between there were several assassinations of political and religious leaders, plus racial tensions in America’s largest cities that led to full-blown riots in the summers of 1964 through 1967. In this decade there were tumultuous developments in the world of entertainment, not only in popular music but also in the TV and film industries.

Popular Music

In popular music the 1960s can be characterized as the decade of the “British Invasion.” When the Beatles arrived in New York on February 7, 1964, the four Liverpudlians were greeted by thousands of screaming young fans, who caused riotous outbreaks at the sites of their first American concerts, including one at Carnegie Hall. The notoriety of the Beatles was enhanced by two appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show. With Beatles songs broadcast live into millions of American homes, parents found themselves on the opposite side of the generational fence from their teenage children. The Beatles craze grew to even greater proportions with the release of the film A Hard Day’s Night that summer.

Although Beatlemania continued throughout the decade, the Beatles themselves remained a group for only a few years. Their last live concert took place in 1966, and by 1970 John, Paul, George, and Ringo went their separate ways, never again to reach the level of acclaim that they had achieved together as the “Fabulous Four.” Other English rock groups like the Rolling Stones, The Who, and Led Zeppelin gained millions of loyal fans; but no matter how successful these groups became, none ever eclipsed the Beatles.

Even the Broadway stage was not immune to the sounds of rock-‘n’-roll. Despite the popularity of such traditionally conceived musicals as Hello, Dolly! (1964) and Funny Girl (1964), which made Barbra Streisand a major singing star, one of the most influential stage musicals of the 1960s was Hair, with music by Galt MacDermot, which was advertised as “an American tribal love-rock musical” when it first opened off Broadway in late 1967. Six months later, a revamped and enlarged production reached the Broadway stage and caused a sensation because of its rebellious attitude toward the war in Vietnam, its frankness about sex, and a nude scene. Hair included a number of songs that became popular, especially “Aquarius” and “Let the Sunshine In,” both of which became hits through a recorded medley made by one of the decade’s most popular singing groups, the Fifth Dimension.

In the late 1960s, the Beatles as well as other performers got caught up in a countercultural phenomenon based on such drugs as heroin and LSD. By 1969, when the first Woodstock music festival took place on a farm in New York State, millions of young people were part of the drug culture, which accompanied the anti-war protests then going on. Such dynamic performers as Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and The Doors’ Jim Morrison, all of whom eventually succumbed to their drug addiction, were among the icons who rebelled against American entanglement in an unpopular war.

Television

With the war in Vietnam continuing to escalate throughout the 1960s, several news telecasts began to run coverage of major events in the conflict. The most successful of these programs was CBS’s 60 Minutes, which debuted in 1968 (and is extant as of this writing). This Sunday evening news hour featured top news correspondents, some of whom reported from locations in Southeast Asia.

In addition to network news programs, TV viewers were often subjected to strong doses of political satire during the 1960s. Two shows in particular dared to ruffle the feathers of corporate sponsors. The first of these was the short-lived That Was the Week That Was, which ran from January 1964 to May 1965. This provocative show was followed in February 1967 by the even more irreverent Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, which included so much unbridled spoofing of everything from politics to religion and beyond that CBS executives suddenly cancelled the show in June 1969.

TV comedy during the 1960s began to reflect a broad spectrum of cultural attitudes. In contrast with such pioneering sitcoms of the ’50s as I Love Lucy and The Honeymooners, many of the newer comedies concentrated on fantasy; this was the case with Bewitched (1964–1972); Gilligan’s Island (1964–1967); and I Dream of Jeannie (1965–1970). Homespun humor was represented by The Andy Griffith Show (1960–1968) and The Beverly Hillbillies (1962–1971). Some 1960s sitcoms were aimed at a more sophisticated audience; this is especially true of The Dick Van Dyke Show (1961–1966), which introduced one of TVs most enduring comediennes, Mary Tyler Moore. This show also set a standard for strong ensemble casts, with support from Morey Amsterdam, Rose Marie, and Carl Reiner, who created the series.

The most successful comedy show at the end of the decade was Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-in, which brilliantly spoofed everything in America and beyond through a quick series of blackouts and short skits. With its rampant one-liners and nonstop gags, this show’s irreverence was in stark contrast to the dire events being reported in the nightly news.

The Carol Burnett Show, though not politically motivated, provided viewers with diversion from newscasts through a variety of entertaining skits and musical numbers. One of TVs finest comedy ensembles, which included Carol Burnett herself, Harvey Korman, Tim Conway, Vicki Lawrence, and Lyle Waggoner, created great hilarity.

Although comedy seemed to dominate prime time TV during the 1960s, a few dramatic programs were successful. In addition to the Westerns such as Gunsmoke, Bonanza, and The Virginian, ABC’s The Fugitive (1963–1967) offered an engrossing series of episodes in which Dr. Richard Kimble (David Janssen) attempted to elude capture as he hunted for a one-armed man whom he believed to be his wife’s murderer. Two series with hospital settings, Dr. Kildare and Ben Casey (both 1961–1966), also furnished viewers with something more substantial than comic relief. In both shows the dramatic content was enhanced by strong background musical themes, provided in the first instance by a neophyte (Jerry Goldsmith) and in the other by a veteran (David Raksin).

The most influential sci-fi series in TV history is Star Trek, which began in 1966 and lasted for three seasons in prime time. Following its cancellation the show began to attract a cult following. “Trekkies” held nostalgic conventions, and by the end of the 1970s, Paramount would launch several feature-length films that reunited most of the original cast members. Additionally, four syndicated TV series would eventually be spun off from the original show.

A major development in TV broadcasting during the 1960s was the gradual conversion to color. Although programs in color had been introduced during the previous decade, it was in the ’60s that a growing home audience of TV viewers began to view prime time shows in color (provided that they could afford the very expensive color TV sets). Even though only 3.1 percent of U.S. households had color TV sets by 1964, that number would increase drastically by the end of the decade.1 The rise of color TV broadcasting was enhanced greatly when NBC announced in mid-1965 that its upcoming fall schedule would primarily be in color. By 1967 the other two networks joined the conversion.

Two other major developments included the transition from live broadcasts to either filmed or videotaped shows and the scheduling of theatrical films in prime time programming. Because of the high cost of buying broadcast rights to major films, movies began to be made specifically for television. By the end of 1966, NBC had struck a deal with Universal to produce a series of original films, which were to be broadcast without prior theatrical showing. By early 1967 all three networks were broadcasting two nights of movies per week.

With the rise of made-for-TV movies, a greater amount of work became available to film composers who could work within the tight time lines and budgets of these productions. Only on rare occasions would musicians be granted the time and the budget to create works on a scale as elaborate as their scores for theatrical films. Even within the restrictions required by this hybrid film genre, many composers contributed some genuinely fine work.

Movies

As the 1960s began, the major movie studios had already started to divest themselves of almost all their production facilities. They remained as corporate entities to oversee the financing of films and often acted as releasing companies for independently produced movies.

Without the rigid controls of the old studio system, feature films made in the 1960s often cost more than $10 million apiece. Because of the impressive box-office returns of such 1950s epics as The Ten Commandments and Ben-Hur, Hollywood producers often fell victim to a belief in “the bigger, the better.” A number of expensive 1960s films drove movie studios to the brink of bankruptcy. Especially ruinous was 20th Century Fox’s production of Cleopatra, which cost about $40 million and failed to show a profit until its TV rights were sold.2

The 1960s may be regarded as the beginning of the end for the screen musical; but, even though song-and-dance films were pretty much a thing of the past, four of the Oscar-winning pictures of the ’60s were musical films. The fact that all four were adapted from highly acclaimed and long-running stage musicals may have contributed to their success. In any case, West Side Story (1961), My Fair Lady (1964), The Sound of Music (1965), and Oliver (1968) were all big hits at the box office, with The Sound of Music becoming the all-time box-office champion (until The Godfather surpassed it in 1972).

So few movies were being shot in black-and-white that the Oscar categories were changed in 1967 to remove any distinction between color and black-and-white filming (which affected the areas of cinematography, art direction, and costuming). Meanwhile, CinemaScope and other processes were replaced as the favored wide-screen technique by Panavision in the early part of the decade. The Cinerama process, used by MGM for two feature films in the early 1960s, was subsequently simplified to a single-projector technique, but was still phased out of existence by the end of the decade.

The 1960s are noteworthy for the arrival of adult films which presented a challenge to the old motion picture production code. When Mike Nichols directed the film version of Edward Albee’s controversial play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in 1966, the code was already outmoded. In 1968, the Motion Picture Association of America replaced the old code with a system of self-regulation, which gave ratings to all forthcoming films. Once this new policy was in place, films with bold, adult themes could be released without fear of being suppressed. Thus, another weapon in the ongoing media war was put in place, as Hollywood began making films that could not be shown uncut on network TV.

For film composers, the 1960s represents the changing of the guard, with some of the noted film pioneers—in particular the three godfathers—composing their last scores during those years. Max Steiner’s declining health, including failing eyesight, forced him to retire in 1965, after thirty-five years of film scoring. His last scores did little to enhance his reputation, and when he died on December 28, 1971, he would be chiefly remembered for the scores of the many exceptional films of the 1930s and ’40s that had given him the opportunity to develop the technique of film scoring to such a high level of artistry. Dimitri Tiomkin composed his last original film score in 1968, for the forgettable comedy Great Catherine. His last involvement with film scoring was arranging the music for the biographical movie Tchaikovsky (1971), which he coproduced in Russia. He lived in retirement for the last years of his life, and died on November 11, 1979. Meanwhile, although Alfred Newman never officially retired, he reached the final chapter in his illustrious film career with the score of Airport whose release coincided with the composer’s death on February 17, 1970.

Franz Waxman, younger than these three pioneers of film scoring, nevertheless preceded all of them in death. Having composed several masterful film scores in the first three years of the decade, including the powerful music of Taras Bulba (1962), he was not much in demand from 1963 on. He succumbed to cancer in 1967 at the age of sixty.

Two other composers, Bronislau Kaper and André Previn (b. 1929), whose film-scoring careers came to an end in the 1960s, had both been affiliated with MGM for most of their Hollywood years. Although Kaper wrote a magnificent score for his last MGM picture, the expensive remake of Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), he began to lose interest in the profession in which he had been involved for almost three decades. He composed six scores between 1964 and 1968, but then turned his attention to other musical pursuits. Although he lived on until cancer claimed him on April 25, 1983, he would make no further contributions to film music.

André Previn’s disdain for the Hollywood atmosphere has been well documented in a number of books, including his own No Minor Chords, an often witty 1991 memoir in which he vividly describes the lack of musical insight shown by Hollywood producers. The title itself alludes to a frequently repeated anecdote about Irving Thalberg, who, having been informed by an assistant that the problems with his newest film stemmed from the composer’s use of minor chords, sent an interoffice memo to the MGM music department in which he instructed all of that studio’s music employees henceforth to avoid the use of minor chords in their scores.3 Despite his increasingly negative attitude, Previn still managed to create some masterful scores for films made in the ’60s, including Elmer Gantry (1960) and Dead Ringer (1964). Previn did four scores for Billy Wilder films between 1961 and 1966, but during this period he began to concentrate on orchestra conducting in the concert hall.

A few efforts in the jazz vein appeared in the 1960s, by composers as divergent as André Previn (The Subterraneans, 1960), Elmer Bernstein (Walk on the Wild Side, 1962), Quincy Jones (The Pawnbroker, 1965), Chico Hamilton (Repulsion, 1965), Herbie Hancock (Blow-Up, 1966), and Michel Legrand (The Picasso Summer, 1969). Because of an increasing tendency toward scores of a jazz or pop sound, the majority of film scores of the 1960s no longer needed composers with a symphonic background. For this reason such masters of the art of film music as Bernard Herr-mann and Miklós Rózsa found themselves being employed less often as the ’60s progressed. Alfred Hitchcock hired Bernard Herrmann for several films in the early ’60s, but by 1965 their relationship ended abruptly with a rift that led Herrmann to leave Hollywood altogether, though he subsequently composed several excellent scores for films made in Europe.

1960

Elmer Bernstein: The Magnificent Seven

The rousing music that Elmer Bernstein composed for The Magnificent Seven, John Sturges’s Western adaptation of Akira Kurosawa’s classic film Seven Samurai, established a sound that energized the scores of many Western films during the 1960s.

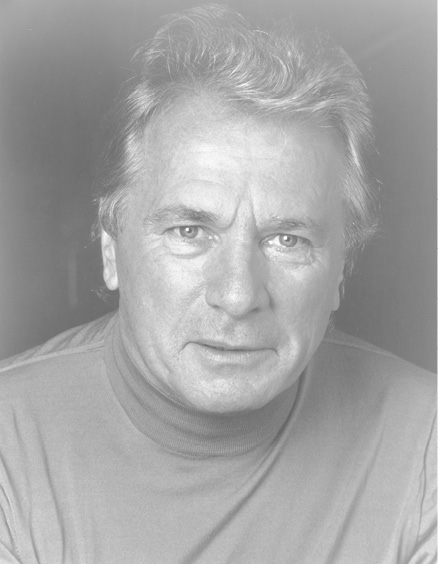

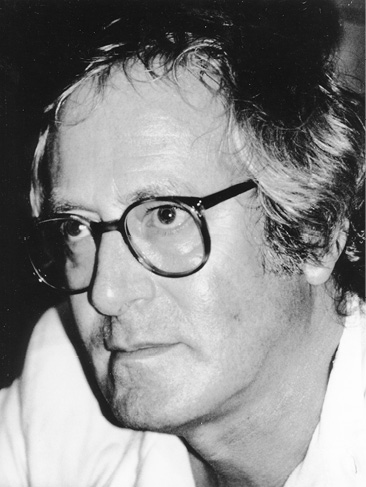

Elmer Bernstein (1922–2004)

Bernstein was born in New York on April 4, 1922. As an only child, he was raised with an appreciation of the arts, and took up painting, dancing, and piano playing. At twelve he received a scholarship to study the piano with Henrietta Michelson at Juilliard and remained her private student until 1949. After graduating from the Walden School in 1939, he went to New York to become a concert pianist. With encouragement from Aaron Copland, Bernstein progressed as a composer by studying with Israel Citkowitz, Roger Sessions, and Stefan Wolpe.* Bernstein also enrolled in composition classes at New York University, but World War II intervened. During a stint in the U.S. Army Air Corps Bernstein was assigned to compose music for radio programs; he also worked as an arranger for Glenn Miller’s Army Air Corps Band.

After the war he tried again to be a concert pianist, but a series of fortuitous events soon paved his way to Hollywood. According to Tony Thomas:

In 1949 [Bernstein] was offered the job of writing a score for the United Nations Radio Service for a program concerning the armistice achieved by the UN in Israel. The program was carried by NBC and was heard by the writer-producer Norman Corwin, who engaged Bernstein to write a score for one of his dramatic productions.†

Sidney Buchman, who was then vice president of Columbia Pictures, heard these shows and invited Bernstein to score two films, Saturday’s Hero and Boots Malone (both 1951).

In 1952, Bernstein produced an unusually modernistic score for Sudden Fear. This score would have cemented Bernstein’s Hollywood career, but his leftist political views proved problematic, due to the ongoing HUAC hearings. Bernstein found himself unable to get big-studio scoring assignments, and in 1953 he wrote music for a pair of films that marked the low point of his career. Ironically Robot Monster and Cat Women of the Moon have both achieved cult status. Fortunately, Bernard Herrmann recommended him for the 1955 20th Century Fox drama The View from Pompey’s Head, which in turn led Cecil B. DeMille to choose him to replace the ailing Victor Young as composer of The Ten Commandments. DeMille’s film rescued Bernstein’s career, which then began to soar with the jazz score of The Man with the Golden Arm, which won for Bernstein his first Oscar nomination.

By the end of the 1950s Bernstein started working with such esteemed directors as Delbert Mann, Anthony Mann, Robert Mulligan, and Vincente Minnelli. In 1960 his work for John Sturges’s Western remake of The Magnificent Seven elevated him to the front ranks of Hollywood composers. Bernstein then achieved great success with To Kill a Mockingbird, The Great Escape, and Hawaii. In the late 1970s he became known for comedy films beginning with National Lampoon’s Animal House. Airport and Ghostbusters also featured Bernstein’s lighthearted music. In the 1980s he started writing small-scale scores such as My Left Foot and Da, which featured the eerie sounds of the ondes Martenot. In 1993 Bernstein wrote one of his finest scores for Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence. He died in 2004 at age eighty-two.

Photo: D’Lynn Waldron

*Tony Thomas, Film Score: The Art & Craft of Movie Music (Burbank, Calif.: Riverwood, 1991), p. 239.

†Ibid., pp. 239–40.

When Sturges decided to adapt Kurosawa’s film, for which he paid a small fee for the rights and received the Japanese director’s blessing, he obtained backing from the Mirisch Brothers at United Artists, but with the provision that he cast a known star in the lead role. Despite his middle-European accent, Yul Brynner was perceived as being a strong, silent presence and thus suitable for the role of Chris, who aids the villagers against a small army of bandits that continually pillages their supplies. Sturges began filming The Magnificent Seven, with its setting shifted from medieval Japan to late-nineteenth-century Mexico. Once Bernstein was hired to do the score, the obvious question was whether there should be a Tiomkin-style ballad. Tiomkin was then the accepted master of the Western genre, having scored High Noon and Sturges’s own Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957). The decision to eschew a song as a vocal background was wise because of this film’s episodic structure. Bernstein’s main-title music sweeps the viewer into a world of roisterous adventure. After some boldly syncopated opening chords, the main theme is heard, with a rising pattern of fifths that is used several times over a continually hard-driving rhythmic accompaniment. This theme, which is heard periodically throughout the film, is associated with Chris and the other six gunmen who have been hired to ward off the bandits. The second most prominent theme is a dramatic idea for brass and drums which begins with three repeated tones, followed by five more that move in a confined melodic range. This music is associated with Calvera (Eli Wallach), the bandit leader.

Though most of the score is up-tempo, especially during the many riding scenes where Bernstein’s music purposefully plays at a faster tempo than the leisurely movement on-screen (another example of the DeMille lesson), there are also moments of a quieter and calmer nature. One especially effective moment occurs when one of the gunfighters, Vin (Steve McQueen), engages Chris in a philosophical discussion of the latter’s motives for helping the villagers. Here the main theme is played more slowly, with an oboe carrying the melody over a background of strings and harp. Elsewhere there are dance pieces for the villagers, as they celebrate moments of respite from Calvera’s attacks. Guitar music can be heard prominently in some of the film’s quieter moments. Tony Thomas’s evaluation of the film is particularly apt:

The Magnificent Seven should not be made the subject of academic discussions. It’s an adventure yarn with some fine action sequences, good color photography by Charles Lang, Jr. of rugged Mexican settings and most conspicuously a music score by Elmer Bernstein that is not so much background as up-front. The music is an integral part of the spirit of the picture and its rhythmic, lilting main theme—later used on television commercials as the Marlboro Country music—remains one of the most popular tunes ever written for the movies, and deservedly so.4

Elmer Bernstein wrote scores for three other films in 1960, each different from the others. These include a score for the documentary Israel with strains of Jewish music, which was written and produced by Leon Uris, author of the best-selling novel Exodus, and the jazz-flavored music for Robert Mulligan’s Rat Race, in which Bernstein was able to further his interests in contemporary jazz sounds for which he had shown so much flair in The Man with the Golden Arm and Sweet Smell of Success (1957). Last, Bernstein composed the romantic background music for the film version of John O’Hara’s From the Terrace. Curiously, the sweepingly lyrical main theme begins with a melodic pattern that is similar to the beginnings of both Jule Styne’s title song from Three Coins in the Fountain and the love theme of Bernard Herrmann’s score of North by Northwest. Despite the similarities, Bernstein’s theme soars in a romantic direction that is all its own. Taken together, these scores indicate Elmer Bernstein’s enormous talent as a film composer, and also show him to be one of the most versatile musicians in Hollywood.

Scores for Historical Epics

The year 1960 was a big one for lavishly produced wide-screen historical dramas that contain memorable background music. For The Alamo, John Wayne’s sprawling epic about the ill-fated Texan stand against a Mexican attack, Dimitri Tiomkin produced a beautiful score with a lot of choral backgrounds. The song “The Green Leaves of Summer,” which Tiomkin wrote for this film, is heard toward the end of the film in an extended arrangement for a cappella voices. Considering the bombastic nature of much of Tiomkin’s music, his understatement in this sometimes meandering but always watchable film is laudable.

Another lavish film is Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus, in which Alex North’s music brilliantly depicts the notable slave revolt against the Roman Empire in 73 BC. Kubrick later disowned his work on Spartacus; but what cannot be denied is the astonishingly detailed action sequences, such as the scene wherein Spartacus (Kirk Douglas) brings together hundreds of fellow ex-slaves in a march to the sea and a final escape from the pursuing Roman army. Alex North’s dramatic score, one of his finest, combines moments of classical beauty with elements of contemporary dissonance. The brilliant piling up of brass tones during the march-like main-title theme provides a strong hint of the overall quality of this score. Two additional pieces of exceptional beauty are the love theme for Spartacus and Varinia (Jean Simmons) and a lyrical serenade for strings and mandolin, which is heard during a peaceful interlude in the camp, where ex-slaves and their families have congregated. This score is arguably the pinnacle of North’s career, though he would continue to write excellent film accompaniments for almost three more decades.

André Previn: Elmer Gantry

Richard Brooks’s dramatically compelling adaptation of Elmer Gantry, Sinclair Lewis’s provocative novel about Bible-toting evangelists during the 1920s, features a powerful performance by Burt Lancaster in the title role. For Gantry, composer André Previn produced one of the most modern of film scores in terms of its dissonant harmony. The dramatically charged main theme, which is based on a seven-note motif, appears throughout the film in a variety of guises. Previn’s music mainly serves to sum up Elmer’s hyperkinetic personality and his impact on the crowds that flock to the tent to hear him preach. The harmony is especially dissonant during the film’s opening credits, where the seven-note idea is accompanied by a series of powerful brass chords.

Among the score’s other original themes, especially noteworthy is the blues tune that is associated with Elmer’s former girlfriend-turned-prostitute, Lulu Bains (Shirley Jones). For the revival meeting scene, old gospel songs such as “Stand Up for Jesus” and “At the River” are sung by Patti Page, who plays Sister Rachel. Finally, when Elmer makes romantic advances toward the evangelist Sister Sharon (Jean Simmons), his motif is slowed down to become less bold and, at the same time, more lyrical.

Short Cuts

Ernest Gold. The Academy Award–winning score of 1960 was Ernest Gold’s dramatic music for Otto Preminger’s lengthy modern epic Exodus. Based on Leon Uris’s novel, Exodus presents a fictionalized version of the events that led to the formation of the modern state of Israel. Its soaring main theme permeates the score with its heroic melody, which is associated with Ari (Paul Newman), Uris’s fictional hero. There is also a lovely theme for the tragic Karen (Jill Haworth) and an occasional reference to “Hatikvah,” the Israeli national anthem.

The Apartment. Billy Wilder’s Oscar-winning movie The Apartment includes one of the year’s most popular musical themes. The score’s composer, Adolph Deutsch, cannot be given credit for this theme since it is based on the 1949 piano piece “Jealous Lover,” by British composer Charles Williams. According to the film’s star, Jack Lemmon, Wilder had a great memory for old songs, even though he couldn’t carry a tune. He remembered this music when The Apartment was being shot, and suggested that it be used as the romantic background theme. It took United Artists some time to track it down. Both The Apartment and the Exodus themes became enormously popular in 1960 through a pair of recordings made by the piano duo of Arthur Ferrante and Louis Teicher for United Artists Records.

Bernard Herrmann. For Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, with Anthony Perkins as Norman Bates, Bernard Herrmann’s often imitated “black-and-white” music, written for strings only, begins with a rhythmically charged idea associated with Marion (Janet Leigh), who flees Phoenix with a bundle of money and drives to California, where she winds up at the Bates Motel. In the film’s most famous sequence, the shower scene, Herrmann devised a series of screechy violin sounds that suggest repeated stabbings with a butcher knife, as Marion is brutally attacked by a shadowy figure. This same music is also used for the second murder, when the investigator, Mr. Arbogast (Martin Balsam), goes snooping around the old house on the hill behind the motel. High-pitched violin harmonics are heard as Arbogast ascends the stairs. When Mrs. Bates jumps out of her bedroom armed with a butcher knife, the screechy sounds return.

Manos Hadjidakis. A new sound in film scoring that became immensely popular in the early 1960s emanated from the background score of Jules Dassin’s Never on Sunday. The film features Dassin’s wife, Melina Mercouri, as Ilya, the fun-loving prostitute of Piraeus, who takes Sundays off so she can read the great Greek plays. The Oscar for Best Song went to the vocal version of this catchy tune, which made Manos Hadjidakis (1925–1994) a composer to be reckoned with. With this infectious score, the Greek bouzouki became an established film-music instrument; it would be heard from several more times, especially in 1964, with Hadjidakis’s music for Topkapi and his fellow countryman Mikis Theodorakis’s flavorful score for Zorba the Greek.

1961

The Henry Mancini–Blake Edwards Collaboration

Of the many long-term collaborations that have existed in the movie business between composers and directors, few have lasted longer nor resulted in more film scores than the thirty-seven-year partnership of composer Henry Mancini and director Blake Edwards.

Henry Mancini (1924–1994)

Mancini was born in Cleveland, where his parents had emigrated from the Abruzzo region of Italy. Mancini grew up mostly in West Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, where he attended local schools. His father introduced him to the flute at age eight, and he also took piano lessons. Mancini decided at an early age that he wanted to compose film music. He described the very day of his decision in his memoir, Did They Mention the Music? After seeing Cecil B. DeMille’s The Crusades in Pittsburgh at age eleven, his already fertile musical imagination was fired.* Subsequent studies at Carnegie Tech and Juilliard involved his taking up the flute as a performance instrument, plus courses in composing and arranging. In 1946, after serving in World War II, he landed a job as a pianist and arranger with the newly reformed Glenn Miller Orchestra led by Tex Beneke.

In 1952 he landed a job at Universal as a member of the music staff. He described the many tasks assigned to him and to others on the staff by Universal music director Joseph Gershenson, who would farm out sections of films to different people.

The music department consisted of Joe Gershenson; his assistant, Milt Rosen; composers Frank Skinner and Hans Salter, who were given complete pictures to score; and, at my level, composers who were assigned the overflow, several of us working on various parts of the same picture. It also included an excellent orchestrator named David Tamkin, who in working on our scores gave us all lessons in orchestration, and a music librarian named Nick Nuzzi.†

Mancini describes the method by which he and fellow staff member Herman Stein were assigned their film-scoring projects:

I would get my five reels and Herman his five. If the love theme fell in his half of the picture, he’d write it, and if he used it in the first half of the picture, I would use it in the second half, and vice versa. The theme, whichever of us wrote it, would be just a melody line, which we would then arrange and give to David Tamkin for orchestration.‡

Mancini admitted that many of the studios’ low-budget films included scores that were compiled by cribbing the music of earlier Universal pictures. Since the studio owned the rights to its movie scores, the original composer had no say in the matter. He indicated that the music librarian would hand off a stack of scores by various composers; the assigned musician would then proceed to make a new score out of them. One score that stands out from Mancini’s days at Universal is the music for Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil (1958). Even though the film was taken away from Welles and reedited, with the music shifted around, Mancini regarded it as one of his proudest moments in film scoring.§

Toward the end of his six-year stint at Universal, Mancini worked on three pictures made by Blake Edwards, including Mister Cory (1957) with Tony Curtis. Edwards and Mancini got on well together, and when Edwards went to NBC with his Peter Gunn project, Mancini scored the series with swingy, jazz-inflected background music. The series debuted in the fall of 1958 and became an immense hit; the music itself became an even bigger success. Mancini produced two albums of Peter Gunn music and won the first of several Grammys. In 1959 Mancini scored Edwards’ second TV series, Mr. Lucky, which won for Mancini two more Grammies.** In the 1960s Mancini scored feature films again, including several directed by Blake Edwards, including Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Days of Wine and Roses, and The Pink Panther. Mancini continued working with Edwards for the next thirty years; he also scored dozens of films for other directors and recorded many successful albums of film music for RCA Victor. Mancini’s career came to an abrupt end with his death from cancer in 1994.

Photo: Photofest

*Henry Mancini, with Gene Lees, Did They Mention the Music? (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1989), p. 75.

†Ibid., p. 63.

‡Ibid., p. 70, 71.

§ Ibid., p. 82.

**Jon Burlingame, TV’s Biggest Hits (New York: Schirmer Books, 1996), pp. 32–33.

The most successful result of their collaboration was Breakfast at Tiffany’s, which was planned as a vehicle for Audrey Hepburn in the role of Holly Golightly, a free-spirited young woman living in New York City. The film’s success was largely based on the song “Moon River,” which was intended for a scene in which Hepburn was to sing while seated on a window ledge strumming a guitar.

The first problem Mancini faced in scoring the film was to convince the producers that he should be allowed to compose the song himself. At that time it was customary to farm out such songwriting jobs to more experienced musicians, but Edwards managed to talk his producers into letting Mancini write it himself. Since Audrey Hepburn was not a trained singer, there was the built-in problem of composing something that she could handle. In his book Mancini tells how he skirted this issue:

Audrey was not known as a singer. There was a question of whether she could handle it. Then, by chance, I sat watching television one night when the movie Funny Face (1957) came on, with Fred Astaire and Audrey. It contains a scene in which Audrey sings “How Long Has This Been Going On?” I thought, You can’t buy that kind of thing, that kind of simplicity. I went to the piano and played the song. It had a range of an octave and one, so I knew she could sing that. I now felt strongly that she should be the one to sing the new song in our picture—the song I hadn’t written yet. . . . It took me a month to think it through. . . . One night at home . . . [I] sat down at the piano, and all of a sudden I played the first three notes of a tune. . . . I built the melody in a range of an octave and one. It was simple and completely diatonic: in the key of C, you can play it entirely on the white keys. It came quickly. It had taken me one month and half an hour to write that melody.5

This was the genesis of “Moon River.” Johnny Mercer’s lyrics, with the enchanting line “Waitin’ ’round the bend, my huckleberry friend,” made the song even more memorable.

The score of Breakfast at Tiffany’s depends mightily on the melody of “Moon River,” which is first heard in an instrumental version during the opening credits, where it is played by a solo harmonica, with guitar, strings, and wordless voices. It is also used in a couple of dramatic scenes to add an emotional quality, especially when Holly tells her upstairs neighbor Paul (George Peppard) how she left home at fourteen. Later it comes in again to underscore the emotional scene where Doc Golightly (Buddy Ebsen), who still thinks he’s married to Holly although the marriage was annulled long ago, gets on a bus to go back to Texas. She tells him that she’s not Lula Mae anymore (that’s her real name!), and that she has a new life in New York. The most crucial use of “Moon River” occurs in the scene, to which Mancini alludes in his book, where Holly is sitting on her windowsill; while accompanying herself on the guitar she sings a serenade for Paul, who listens from an upstairs window.

There is much more to the music, such as the up-tempo jazz numbers and a cha-cha tune for the extended party scene in Holly’s apartment, which ends abruptly when her Japanese landlord Mr. Yunioshi (Mickey Rooney, in a hilarious role) calls the police. Then there’s the “walking” theme, a catchy tune for wordless voices, strings, and xylophone, which accompanies Holly and Paul as they traipse around Manhattan. First they go to Tiffany’s, then to a library, and finally to a dime store, where they shoplift a pair of Halloween masks, put them over their faces, and then slowly walk out of the store without being detected.

One of the score’s most noteworthy features is a stinger chord (one that draws the viewer’s attention) which punctuates several scenes, with a vibrato effect created by the use of vibraphone plus several other instruments, including piano and harp. The score of Breakfast at Tiffany’s succeeds in capturing the many moods of New York, with an instrumentation that would lead to other scores in which the conventional orchestration would be replaced by a jazzier, swing band type of sound. This aspect of the score was illuminated in 1987 by Gene Lees in his preface to Mancini’s book Did They Mention the Music?

In Breakfast at Tiffany’s Mancini was revealed as an inventive and original writer who enormously expanded the vocabulary of modern orchestration. An awareness of classical orchestration was wedded to a fluency in American big band writing, to sometimes startling effect. This combination made Mancini the first film composer to emerge from the anonymity of that profession and become a public figure, a man known worldwide.6

The two Oscars Mancini won, for the film’s score and for “Moon River,” guaranteed him a long-lasting career in Hollywood. He continued to write film scores for the next three decades, during which he collected two more Oscars (for the 1962 title song for Days of Wine and Roses and for the song score of the 1982 Victor/Victoria). Perhaps the most successful fruits of the Mancini-Edwards collaboration began with The Pink Panther (1964), which spawned a series of films featuring Peter Sellers as the bumbling Inspector Clouseau. In all, Mancini composed the scores for eight Pink Panther films.

Miklós Rózsa: Scoring Samuel Bronston’s Epics

Because of the slow but steady decline of the studios during the 1950s, combined with the gradual dissolution of the studio music departments, the selection of composers to score films became the independent producer’s responsibility by the beginning of the 1960s. This development would ultimately hurt film scoring because those holding the purse strings were often not musically informed. One master composer who still did get called on was Miklós Rózsa, who scored King of Kings and El Cid, both produced by Samuel Bronston released in 1961. The music of King of Kings is marked by a direct, emotional approach to the Christ story, with a stirring main theme that ties the various episodes of the picture together. Unlike Rózsa’s earlier Ben-Hur score with its spectacular brass scoring, this film score primarily features strings.

For El Cid, starring Charlton Heston as the legendary Spanish hero, Rózsa traveled to Madrid to do research. He later described this experience:

There was research to do, because I knew nothing of Spanish music of the Middle Ages. The historical adviser on the film was the greatest authority on the Cid, Dr. Ramon Menendez Pidal, aged ninety-two. It was he who introduced me to the twelfth-century Cantigas of Santa Maria, in one of what must have been at least ten thousand books in his vast and beautiful library. . . . I spent a month in intense study of the music of the period. I also studied the Spanish folk songs which Pedrell had gone about collecting in the early years of this century. With these two widely differing sources to draw upon, I was ready to compose the music. As always, I attempted to absorb these raw materials and translate them into my own musical language.7

The finished product is a masterpiece of symphonic film music that harks back to the Golden Age. The prelude, used for the opening credits, is a showcase for two of the score’s principal themes. The first is an upward-arching melody that conveys the heroic character of Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar, known in legend as “El Cid,” or Cid Campeador (Lord Conqueror). The second is an inspired love theme, which compares with the many lyrical themes Rózsa composed for his earlier epic scores, such as for Quo Vadis and Ben-Hur. Scattered throughout the film’s background music are several majestic fanfares, played by an expanded brass section, and dramatic marches, including the “El Cid March” and “Entry of the Nobles.” With this epic score and the dramatic King of Kings music, Rózsa rightfully regarded 1961 as “the climax and watershed of my film career.”8

Elmer Bernstein: Both in and out of the Saddle

Continuing in his Western vein, Elmer Bernstein created a rousing background for Michael Curtiz’s last film, The Comancheros, with John Wayne as a Texas Ranger. While this score’s principle melodic idea resembles the Magnificent Seven theme, it avoids being a carbon copy.

Bernstein’s other film-music accomplishments in 1961 include a romantic-styled background for By Love Possessed; the rhythmically driven modernistic music for the potent hospital drama The Young Doctors; and his best score of the year, the Oscar-nominated music for Peter Glenville’s film adaptation of Tennessee Williams’s Summer and Smoke.

This last film, a colorfully produced period drama set in a small Mississippi town in 1916, concerns the sexual frustration of Alma Winemiller (Geraldine Page), a minister’s daughter who cannot openly express her feelings for her neighbor John Buchanan (Laurence Harvey), a restless medical student who feels pressured to follow in his physician father’s footsteps. Bernstein’s main theme features a melody that defines the character of Alma. Over a restless harmonic background Bernstein designed a widely arching melodic line which features tones that leap upward, only to fall back down in pitch. The prevailingly downward spiral of this melody conveys an unavoidable sense of melancholy—a key to the underlying tragedy of the frustrated love that causes the destruction of Alma’s fragile personality. A series of solemn brass chords with accompanying pairs of soft woodwind tones is also featured as punctuation for this theme, the various elements of which add poignancy to Williams’s story. The depth of Bernstein’s perception of Alma may be heard throughout this emotionally moving score.

Short Cuts

Bernard Herrmann. The Charles Schneer–Ray Harryhausen film Mysterious Island features a turbulent Bernard Herrmann score. Although the resulting music isn’t as tuneful as his 7th Voyage of Sinbad, there are stunningly dramatic moments featuring an expanded brass section of eight horns and four tubas, plus lots of percussion. The prelude is a bombastic piece consisting of long, sustained chords played by brass and woodwinds, with punctuating drums and cymbal crashes. The opening scene, in which a small group of fugitives escapes from a Confederate prison in an observation balloon, features a wildly rhythmic piece, with swirling woodwind figures in triplet rhythm accompanying heavy brass chords and percussion effects.

The most ingenious parts of the score accompany scenes on an uncharted island in which gargantuan species are encountered: for a giant crab, the music features the eight horns plus more pounding chords by brass and percussion; for a giant bee, the orchestra becomes a buzzing machine, with string tremolos, woodwind trills, and flutter-tonguing in the brass; and for a giant bird there is a Baroque-style fugue that begins in the low woodwinds and eventually features several different instrumental colors in a wildly inventive orchestral romp.

Dimitri Tiomkin. One of the biggest box-office hits of 1961 was the World War II action adventure The Guns of Navarone, the first and best of several films based on stories by Alistair MacLean. Dimitri Tiomkin, in a respite from Western films, gave this score a very driving beat, as in the main-title music, known as the “Legend of Navarone,” in which the trumpets boldly proclaim an emotionally stirring march-like melody, followed by a second theme of heroic character featuring soaring strings.

Hugo Friedhofer. The troubled Marlon Brando film One-Eyed Jacks emerged as a major disappointment in 1961, despite some fine acting moments, but Hugo Friedhofer produced one of his finest scores on its behalf, with a main theme of noble character played by trumpets over a background of strings. Friedhofer, one of the most underrated of all film composers, would write only six film scores in the entire decade.

Laurence Rosenthal. One of the younger composers in films, Detroit native Laurence Rosenthal (b. 1926), wrote a fine score for Daniel Petrie’s memorable film version of Lorraine Hansberry’s stage play A Raisin in the Sun. Rosenthal produced a highly sympathetic accompaniment for the plight of a proud black woman, Lena Younger (Claudia McNeil), who wants to use the insurance money left behind by her late husband to move her family from their cramped Chicago apartment. Rosenthal’s principal theme features a melody of noble simplicity, which climbs upward by thirds (C–E–G–B flat) before returning down the scale. The upward reaching of the pitches is an indication of Lena’s dogged determination to make a better life for her family.

1962

Maurice Jarre: Lawrence of Arabia

At the end of the 1950s, a group of young French filmmakers, known as La Nouvelle Vague (the New Wave), including François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Jean-Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer, and Louis Malle, favored a more personal, free style of filmmaking, as opposed to the older, more formally structured films. By the early 1960s, many of these films were being shown on American screens.

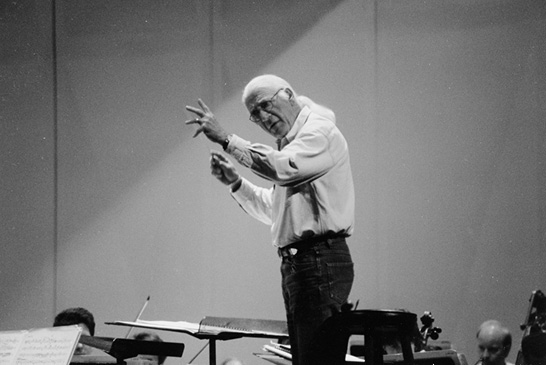

Maurice Jarre (1924–2009)

Maurice Jarre, who was born in Lyon, did not come from a musical background; his father was a technical director for a local French radio station. Maurice’s formal introduction to film music came at age sixteen when he played percussion instruments in a music ensemble. He enrolled at the Paris Conservatory as a percussion student, and numbered Louis Aubert and the renowned Arthur Honegger among his teachers.* During military service Jarre played percussion in a naval band, and he later became a timpanist with a Paris orchestra.

Jarre’s composing career began with music for the stage. In 1950 French actor Jean Vilar relaunched the Théatre Nationale Populaire, and asked Jarre to compose scores for such plays as Richard III, Don Juan, and Macbeth. In 1952 film director Georges Franju hired Jarre to compose a score for his short documentary film Hotel des Invalides. Franju retained Jarre’s services for the rest of the decade, by which time Jarre had composed music for several ballets and concert works, including his Concerto for Percussion and Strings (1956).

Through the 1950s Jarre scored films by several prominent French directors; in 1960 he wrote the music for his first English-language film, Richard Fleischer’s Crack in the Mirror, which starred Orson Welles. Shortly thereafter, Jarre scored the film Sundays and Cybele, which led to an invitation to compose the score for David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia.

After winning the Oscar for this score Jarre became one of the most in-demand composers in Hollywood. He wrote music for all of Lean’s subsequent films, including Doctor Zhivago, and scored many other prestigious films throughout a career that extended almost a half century. In the 1980s he pioneered in the use of multiple synthesizers to score films; the Maurice Jarre Synthesizer Ensemble is credited with performing his music for such films as Witness and Fatal Attraction. His last film score was for the TV movie Uprising, made in 2001. Jarre died in 2009.

Photo: Private collection of Laurence E. MacDonald

* Ann Mills, liner notes, Maurice Jarre at Royal Albert Hall, Milan CD no. 73138 35793-2.

One of the side effects of the New Wave was the creation of musical scores by several French composers, some of whom had scored documentary short subjects in the early 1950s, but by the end of the decade had made the transition to scoring feature-length films. Among these were four who became internationally famous during the 1960s: Georges Delerue (1925–1992), Michel Legrand (b. 1932), Francis Lai (b. 1932), and Maurice Jarre (1924–2009). All of them eventually won Oscars for English-language films. Jarre won a total of three Academy Awards, including one for Lawrence of Arabia.

In 1962 Maurice Jarre scored the French film Sundays and Cybele, which won the 1962 Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. His music for this film so impressed producer Sam Spiegel that he invited Jarre to take part in composing the score for Spiegel’s epic saga about T. E. Lawrence that was being directed by David Lean.

During the filming of Lawrence of Arabia, with newcomer Peter O’Toole as the enigmatic hero, Spiegel informed Jarre that three composers were going to contribute music to the film. Armenian composer Aram Khachaturian was to write the Arabian music while Benjamin Britten was to compose the British music. Spiegel wanted Jarre to compose the dramatic music for the balance of the film. Jarre was perplexed by this arrangement and was relieved when he learned that neither Khachaturian nor Britten was available.9

Spiegel had yet another composer up his sleeve—Richard Rodgers, with limited dramatic underscoring experience. When the film had been edited down from the forty hours of rough cut to its final running length of just less than four hours, Spiegel gathered together Lean, Jarre, and a pianist, who was called upon to demonstrate some of Rodgers’s themes. When Lean expressed his dislike for this music, Jarre was asked to demonstrate his own music. Lean was so pleased with the grandiose main theme for Lawrence that he urged Spiegel to give Jarre the entire scoring job. There were only four weeks remaining before the premiere. Jarre remembers the exhausting task of completing the project: “Working like crazy, day and night, I barely survived this experience, having to do everything in such a short time. I was only sleeping two or three hours per night.”10

The most obvious thing about Lawrence of Arabia’s music is its sheer size. To construct a score which would have a sense of grandeur comparable to the wide-screen images of the desert vistas, Jarre employed an enlarged orchestra, plus the electronic ondes Martenot, the eerie sounds of which were used to suggest the eternal mystery of the Arabian desert expanse. He also used an old string instrument called the kithara, which is a type of lyre, the string tones of which contribute an exotic flavor to the score.

The main theme, which makes repeated use of a descending fourth (C–G), lends a romantic aura to Lawrence’s adventures as a British soldier sent into the Arabian desert in 1916 in order to organize the Arabs against the Turkish army. Although Robert Bolt’s script never quite solves the riddle of who Lawrence really was, Jarre’s music, with its combined British and Arabic elements, indicates that he had divided loyalties. The British flavor is brought out in the “Home” theme, which suggests his British roots. The Arabic flavor comes across in the “Arab” theme, which suggests Middle Eastern music through the use of scales with lowered tones. As a nod to the British flavor, Jarre was persuaded to incorporate a borrowed march theme, “The Voice of the Guns,” written by Kenneth J. Alford.

Spiegel insisted on using famed conductor Adrian Boult to lead the London Philharmonic in the recording sessions for the film, but Boult conducted only the overture, with Jarre doing the rest. In the film’s credits, Boult is listed as the conductor of the entire score, whereas, on the film’s soundtrack recording, Jarre is listed as the sole conductor.

Even before the release of Lawrence, Jarre became involved with another wide-screen epic, Darryl Zanuck’s meticulously staged re-creation of the D-day invasion, The Longest Day, which at the time was the most expensive black-and-white film ever made at a cost of $8.5 million.11 Although the main march theme is based on a song composed for the film by one of its costars, Paul Anka, Jarre was commissioned to compose additional music and to do the orchestral arrangements of Anka’s tune. The result was an appropriately patriotic score.

Because of the combined box-office successes of The Longest Day and Lawrence of Arabia, plus Lawrence’s seven Oscars (including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Music Score—Substantially Original), Jarre was virtually assured of more scoring projects. And because of his friendship with David Lean, one of these projects was one of the most eagerly anticipated films of the decade: Leans’s epic version of the Boris Pasternak novel, Doctor Zhivago.

Two by Elmer Bernstein

One of the finest scores of the 1960s is from Robert Mulligan’s film of Harper Lee’s autobiographical Pulitzer Prize–winning novel To Kill a Mockingbird. Elmer Bernstein’s lyrically inspired, often gentle music reflects the childlike wonder that is at the heart of this story of two small children in Alabama during the Depression and their reactions to the dire events that occur around them. Especially serious is the trial of a black man, falsely accused of raping a white woman. He is defended by the children’s father, Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck).

Although there are some melodramatic plot turns, including an assault on the children by one of the white townspeople, the score is filled with charming moments. The main-title theme is a lilting tune first played by solo piano, and then by a flute with a repeated harmonic motif on the accordion, followed by strings which swell up in a full thematic statement. For the scene in which Scout (Mary Badham) is curled up in an old tire and rolls up to the porch of the house where the feared Boo Radley lives, the music has a Coplandesque flavor, with many syncopated chords and sudden pauses. The music conveys a great sense of compassion for the children in this film, which is narrated by Scout as an adult (with the voice of Kim Stanley). This is a film full of wondrous things, not the least of which is Bernstein’s memorably eloquent music.

Bernstein also composed a noteworthy score for a film set in New Orleans, Walk on the Wild Side, the main theme of which (with lyrics by Mack David) received an Oscar nomination as Best Song. It is most memorably heard in a bluesy instrumental version played over the film’s clever opening credits, during which several cats are seen slowly prowling about. The music of Walk on the Wild Side is a worthy companion to such earlier jazz-inflected Bernstein scores as those for The Man with the Golden Arm and Sweet Smell of Success.

Two Scores by Bernard Herrmann

The music in J. Lee Thompson’s thriller Cape Fear invites comparison with much of Herrmann’s music for Alfred Hitchcock films. In the main-title theme, Herrmann utilized a dramatic four-note melodic idea that recurs throughout the film—an ominous series of brass tones that descend through the octave. These tones suggest the menacing presence of Max Cady (Robert Mitchum). Cady is stalking the family of his defense attorney (Gregory Peck), whose purposely botched defense of the dangerous Cady caused him to be imprisoned. The score overall is taut and compelling, filled with tensely dramatic chords.

Herrmann’s other 1962 score is also one of his most romantic. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night was made into a handsomely produced film by veteran director Henry King, who had earlier made The Snows of Kilimanjaro, which includes another eloquent score by Herrmann. This time, Herrmann’s creativity was impaired somewhat by the use of a title song composed by Sammy Fain and Paul Francis Webster. Herrmann’s cues feature a few references to this melody along with several of his own lyrical ideas. Overall, the romantic qualities in Herrmann’s music suggest that he excelled in a genre far different from the thrillers with which he is so often associated.

Short Cuts

André Previn. One of the most dramatic scores of 1962 was André Previn’s lushly orchestrated music for MGM’s expensively mounted remake of The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Despite the many deficiencies of this film, the main-title theme, with a pounding drumbeat accompanying the full orchestra, creates a powerful impact. The other principal musical idea is a rhapsodic love theme, with a solo violin sounding above sustained orchestral chords.

Bronislau Kaper. MGM’s other mammoth 1962 movie was another remake, Mutiny on the Bounty. Like Four Horsemen, it required a big orchestral score. The main theme is a magnificent musical tapestry that conjures up the drama of the sea, sailing ships, and the expectancy of setting sail for the South Pacific as Captain Bligh prepares an expedition to find the tropical breadfruit plant and take specimens of it back to England.

Although the film itself is thrown off course by Marlon Brando’s bizarre interpretation of Fletcher Christian as an English dandy, Kaper’s score remains a work of superbly dramatic eloquence, with a terrifically dynamic accompaniment for the storm sequence, plus a lyrically exotic melody for the scenes on Tahiti. The melody is called “Love Song from Mutiny on the Bounty (Follow Me),” with words by Paul Francis Webster. One of the most memorable uses of this theme occurs when a group of Tahitian natives sings it as a native chant in a cappella style.

Jerry Goldsmith. Goldsmith, who had been writing film music since 1957, began to show significant signs of artistic growth with the scores of two films made by Universal in 1962. He demonstrated a remarkable ability to adapt his style to whatever genre seemed appropriate for the film at hand. For example, in Lonely Are the Brave, a compelling drama of a cowboy (Kirk Douglas) at odds with modern technology, Goldsmith’s music seems to emulate the Western style of Elmer Bernstein’s Magnificent Seven, whereas in Freud, one of his most dissonant scores, he chose to flavor the film with Herrmannesque sustained brass chords accompanied by faster-moving strings. This score, for which he received his first Oscar nomination, is uncannily vague in terms of tonality. It seems to mirror the atonal works of Arnold Schoenberg, which emanated from the time when Sigmund Freud was upsetting the medical community in Vienna with his revolutionary theories about the subconscious.

Franz Waxman. Nearing the end of his career, Franz Waxman contributed fine scores for the 1962 films Taras Bulba and Hemingway’s Adventures of a Young Man. The former is distinguished by a romantic large-scale orchestra score, which flavors this Nikolai Gogol story of a Cossack family. Especially memorable is the scene in which the Cossacks gather a fighting force as they ride en masse to the city of Dubno. The “Ride to Dubno” music begins softly, but soon grows to a wild, full-orchestra tumult.

The Hemingway score is smaller in scale, but has some compelling dramatic moments, including the theme for Billy Campbell (Dan Dailey), whose alcoholic character is musically accompanied by a piece called the “D. T. Blues,” featuring a bizarrely out-of-tune piano set against the harmony of strings. For the soundtrack recording, the piano part was played by John Williams, who at the time frequently found employment recording film scores by other composers.

Henry Mancini. Two of the scores that Henry Mancini composed in 1962 continued his collaboration with Blake Edwards. Experiment in Terror employs tense, stark background music; Days of Wine and Roses is an early example of the monothematic score, that is, a score built on a single melodic idea—that of the song Mancini wrote for the film with lyricist Johnny Mercer. This melancholy ballad went on to win for Mancini and Mercer their second consecutive Best Song Oscars. Throughout this engrossing drama, the melody is heard in a variety of tempos to accompany the story of Joe Clay (Jack Lemmon), who introduces his wife Kirsten (Lee Remick) to drink. Eventually they both become alcoholics. While Joe learns to handle his dependency through Alcoholics Anonymous, Kirsten refuses to stop drinking and they become separated, with Debbie, their younger daughter (Debbie McGowan), in Joe’s custody. In the final scene, when Kirsten visits Joe in a hotel room where he and Debbie reside, Joe tries one more time to convince Kirsten to get help, but she refuses the offer. Here Mancini’s slow-moving melody contributes an almost heartbreaking poignancy to this tragic story of a marriage that is destroyed by alcohol.

Mancini also produced a memorable score for Howard Hawks’s Hatari!, in which he accompanied the adventures of big-game hunters in Africa. Most notable is the music entitled “Baby Elephant Walk,” which features a boogie-woogie bass accompanying a tune played on an electric calliope.

Laurence Rosenthal: The Miracle Worker. Following his emotion-charged music for A Raisin in the Sun, Rosenthal produced another memorable score for the film version of William Gibson’s award-winning play, The Miracle Worker. Director Arthur Penn allowed Rosenthal’s music to set the mood at the very opening, as young Helen Keller (Patty Duke) is first seen meandering blindly among rows of sheets hanging on an outdoor clothesline. Here the folk tune “Hush, Little Baby” is cleverly interwoven with Rosenthal’s original theme; this blended music provides an emotional quality to many ensuing scenes as the Keller family entrusts a teacher named Anne Sullivan (Anne Bancroft) with the arduous task of educating their terribly impaired daughter.

In the film’s climactic scene, as Helen discovers a way to say “water,” with Anne reacting with great amazement, the music crescendos to a highly intense level. Rosenthal’s music is also very effective in the film’s quieter moments, especially at the end, when Anne holds Helen in her lap and assures the child of her love.

Footnote To 1962

In 1962, the first film based on the spy novels of Ian Fleming appeared. Although the music for Dr. No is credited to an English songwriter named Monty Norman, there is controversy about the authorship of the now-famous James Bond theme. The difficulty stems from Norman’s guitar melody, which was turned over to John Barry (1933–2011) for a makeover. Barry shifted the melody down an octave and added both a rhythmically driven accompaniment and a brash countermelody for trumpets. Norman subsequently demanded sole credit for this theme and received a legal ruling in his favor. Despite Norman’s claim, Barry deserves much of the credit for the effectiveness of this theme, which has been featured in almost every James Bond movie.

1963

John Addison: Tom Jones

In 1963, the relatively obscure John Addison (1920–1998) became the third English composer to win an Oscar (after Brian Easdale in 1948 and Malcolm Arnold in 1957)—for Tom Jones.

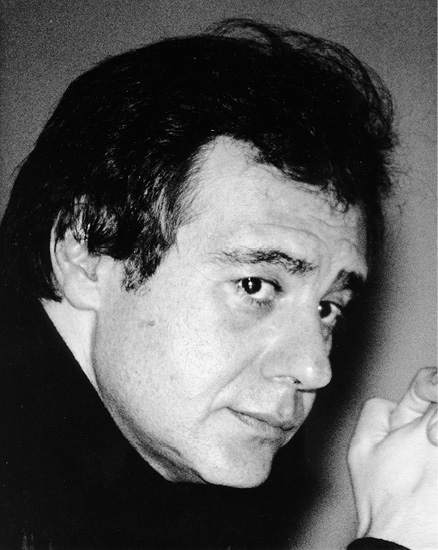

John Addison (1920–1998)

Addison is one of the most prolific British film composers of the twentieth century, with a résumé of over sixty scores for films and TV shows written over a period of more than forty years. As the son of a British Army colonel, the young Addison received his basic education at Wellington College, a school for sons of the military. At sixteen he enrolled in the Royal College of Music, where he studied composition with Gordon Jacob, oboe with Léon Goossens, and clarinet with Frederick Thurston. His studies were interrupted by World War II, in which he served with the British XXX Corps in the 23rd Hussars. He was a tank commander in the Battle of Normandy and wounded at Caen.* He then took part in Operation Market Garden, a failed military deployment that was commemorated in the film A Bridge Too Far (1977), which features Addison’s music.

After the war he returned to college, received his degree, and taught composition at the Royal College. A chance meeting with a war buddy, Roy Boulting, led to his first film score, which was written for the Boulting Brothers’ production Seven Days to Noon (1950).

During the 1950s Addison divided his composition time between writing film scores and composing concert pieces. In 1959, not only was his ballet music for Carte Blanche performed at the Edinburgh Festival, but he scored the film version of Look Back in Anger, produced by the newly formed Woodfall Film Productions, which was spearheaded by playwright John Osborne and director Tony Richardson. For the film The Entertainer (1960), Addison created the score by adapting the songs he had written for the stage production. Subsequent Woodfall productions included A Taste of Honey and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, both of which featured Addison’s music. These projects led to the film that elevated all of these creative people to celebrity status: the 1963 Oscar-winning film based on Henry Fielding’s bawdy novel Tom Jones.

This film paved the way for many other popular films; in 1965 Addison was chosen to replace Bernard Herrmann’s score for Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain. His lyrical saxophone theme was a far cry from Herrmann’s bombastic French horn music. He also filled in for Herrmann as composer of The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (1976), which was in production when Herrmann died. Addison achieved late recognition as composer of many episodes of the TV series Murder She Wrote. He retired a few years before his death in 1998.

Photo: Gay Goodwin Wallin

*Tony Thomas, Film Score: The Art & Craft of Movie Music (Burbank, Calif: Riverwood, 1991), p. 134

Although the novels of Henry Fielding (1707–1754) have been widely read for several centuries, until the Woodfall production of Tom Jones, no film adaptation of Fielding’s work had ever been attempted. Part of the problem may have been the lusty sexual humor in Fielding’s stories, which satirize eighteenth-century society and its social conventions. The new openness of the cinema in the early 1960s convinced the makers of Tom Jones that they could adapt this story without emasculating its substance. The finished film proved them to be right: as directed by Tony Richardson from John Osborne’s script, and with John Addison’s richly textured musical score, Tom Jones became the movie sensation of 1963. All three of these individuals were rewarded on Oscar night in early 1964, when Tom Jones collected a total of four Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Direction, Best Screenplay, and Best Music Score.

In the film, Tom (Albert Finney) grows up as an illegitimate child who has been raised by the prosperous Squire Allworthy (George Devine) at the latter’s country estate. Tom’s prospects, which are limited because of his dubious background, seem to take a turn for the better when he falls in love with Sophie Western (Susannah York), but her father, Squire Western (Hugh Griffith), objects to the match. Tom then sets out to see the world, and after many adventures (and misadventures) he is found to be of noble birth and can take Sophie as his bride.

What ultimately makes Tom Jones work so well is that Addison played along totally with Richardson’s freewheeling directorial style. Addison tried such novel ideas as the combination of an out-of-tune piano with a harpsichord for the opening silent sequence. After establishing the main theme, a rapid-paced idea full of repeated notes, Addison introduced the film’s love theme, a lilting idea for piano in the style of a waltz. In addition to the score’s two primary themes, there is a jaunty idea for saxophone, guitar, and various woodwinds, which appears several times. There is also a comical reference to the hymn “O God Our Help in Ages Past.” Overall, Addison’s music is an eclectic mixture of styles, but it works wonderfully in this rollicking film.

There would be further film adaptations of eighteenth-century novels, including The Amorous Adventures of Moll Flanders (1965), based on Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders and directed by Terence Young, the first James Bond director, and Joseph Andrews (1977), based on the Fielding novel, which Richardson himself directed. Despite the physical beauty of these productions, and despite John Addison’s witty music for them, they do not compare favorably with Tom Jones, which remains a cinematic romp.

Alfred Newman: How the West Was Won

By 1963, few Hollywood producers were inclined to utilize the talents of composers who had been around since the early days of the talkies. Fortunately, when MGM launched its wide-screen production of How the West Was Won, the second Cinerama film to feature a continuous scenario rather than a travelogue format, Alfred Newman was chosen to do the scoring. The movie covers several generations of pioneers who braved the elements to move westward across the American frontier. The resultant score is definitely old-school in its design, but still makes a powerfully dramatic contribution to this episodic but entertaining film.

Newman’s main theme is a heroic melody, which is first stated by French horns, with support by the full orchestra. This is followed by a variety of themes, both new and borrowed. Debbie Reynolds, one of the film’s stars, sings a number of songs, including “Home in the Meadow,” with a melody based on the English folk song “Greensleeves.” Additionally, there is a lot of choral singing, provided by the Ken Darby Singers. For the initial reserved-seat showings of this film Newman and Darby collaborated on two extended choral pieces, an overture and an entr’acte, in which such old American songs as “Shenandoah,” “I’m Bound for the Promised Land,” and “Battle Hymn of the Republic” are incorporated. Several references are also made to “When Johnny Comes Marching Home”; it is used in the film’s central episodes, which are devoted to the Civil War. This score is a collage of many parts, which fit together nicely to make a stirring musical portrait of the American West.

Short Cuts

Bernard Herrmann. Herrmann wrote powerful music for Jason and the Argonauts, his fourth and last score for the production team of Charles Schneer and Ray Harryhausen. To accompany this grand mythological fantasy, Herrmann employed a huge brass section, which is heard most splendidly in the majestic main-title theme, with an accompaniment of woodwinds, harp, cymbals, and pounding drums. (Herrmann used no orchestral strings at all in his scoring of this film.) This music is yet another fine example of the composer’s fertile imagination let loose on a cinematic fantasy that demanded colorful scoring.

Dimitri Tiomkin. As a follow-up to his exciting music for The Guns of Navarone, Dimitri Tiomkin was hired in place of Miklós Rózsa to score Samuel Bronston’s epic, 55 Days at Peking, an entertaining if highly fictionalized account of the Boxer Rebellion in China. Amid much spectacular pageantry and battle music, Tiomkin contributed a beautifully melancholy love theme for the American major (Charlton Heston) and the Russian baroness (Ava Gardner), heard both as an instrumental waltz and as the melody of the song “So Little Time,” which, along with the score, was nominated for an Oscar.

Miklòs Ròzsa. Miklós Rózsa, underemployed as a film composer during the 1960s, produced only his fourth score of the decade in 1963 when he composed the memorable music for MGM’s multi-star drama The V.I.P.s, for which he returned to the expressive style of scoring that he had used so effectively in such earlier films as Lydia and Madame Bovary. The main-title theme of The V.I.P.s is a sweepingly romantic piece played by soaring strings and French horns. For Margaret Rutherford, who won an Oscar in a hilarious supporting role as a dotty duchess, Rózsa wrote in a rare comical vein. This theme, which features a recorder playing a jaunty tune accompanied by harpsichord, is one of his cleverest bits of orchestration. This music also has a decidedly Scottish flavor, with a middle section that sounds like an imitation of bagpipes.

Riz Ortolani and Nino Oliviero. The year’s most unexpected success, both as movie and as theme music, is the Italian documentary Mondo Cane, with a musical score by Riz Ortolani (b. 1931) and Nino Oliviero (1918–1980). When the film was released in America with a narration that was dubbed into English, a vocal rendition of one of the background themes, entitled “More,” with English lyrics by Norman Newell, was recorded for the English soundtrack. “More” was nominated for an Academy Award and became the top song of the year, with a stint on the Billboard charts of twenty-five weeks, eight of which the song was number one. This song helped the film reach a wide film-going audience that might otherwise have ignored it.

Elmer Bernstein. Although the scoring of some of the films Elmer Bernstein worked on is sparse, including Martin Ritt’s Hud and Robert Mulligan’s Love with the Proper Stranger, he once again had a rich scoring opportunity with Hall Bartlett’s mental hospital drama The Caretakers. Beginning with a brassy main-title theme that evokes his earlier jazz-flavored scores, such as for Sweet Smell of Success, this score has quite a variety of styles; at times it is reminiscent of Summer and Smoke, at other times it has the gentler sound of To Kill a Mockingbird. The most noteworthy scoring effect is the use of string harmonics in a bit of the nursery tune “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.” Altogether, this is an effective scoring achievement.

Bernstein’s most memorable score of 1963 came with the military-flavored music of The Great Escape. The main theme is a jaunty march tune, which begins simply and gradually builds up until it reaches a heroic level. In the later stages of the film, in which several American and British POWs dig their way out of a German prison camp, Bernstein capitalized on the opportunity to produce some rhythmically charged chase music.

Jerry Goldsmith. Of Jerry Goldsmith’s six scores for 1963 films, Lilies of the Field deserves mention for its clever orchestration, which includes harmonica, banjo, and strings played in the manner of country music. For this touching story of Homer Smith, an itinerant black man (Sidney Poitier) who gets conned into building a chapel for a group of German-immigrant nuns in a desert area of Arizona, Goldsmith borrowed the old spiritual “Amen,” which is heard several times in the film. It provides moments of humor, as when the nuns are taught to sing the word “amen” repeatedly while Homer sings a text about Jesus. Although Poitier’s singing voice was dubbed by famed black singer and choral director Jester Hairston, he looks very believable in the musical scenes. The “Amen” melody is also used as background scoring; a banjo, a harmonica, and other solo instruments are heard in melodic variations on the tune.

André Previn. The film version of the hit musical Irma la Douce is a bit of a curiosity. Billy Wilder decided to discard the songs from the stage version and instead hired André Previn to compose a background score that would incorporate bits of the musical’s song melodies. The result, about ninety percent original music, is some of the most tuneful work of Previn’s career. The main-title theme is in the style of a cancan, filled with boisterous rhythmic vivacity, while Irma’s theme is a charming waltz for accordion, flute, and strings. The originality of this score might lead one to ponder why Previn’s work won an Oscar in the category Scoring of Music—Adaptation or Treatment.

Footnote to 1963

The most unusual-sounding background “score” of the year consisted of electronically produced bird sounds, which were utilized in providing a sonic atmosphere for Alfred Hitchcock’s chilling movie The Birds. Bernard Herrmann served as a sound consultant on the film, but refrained from writing musical backgrounds. Ordinarily, the avoidance of music in a thriller would be a mistake, but in this film the eeriness of the bird sounds conveys a great deal of tension.

1964

Laurence Rosenthal: Becket

Although Laurence Rosenthal has composed scores for fewer than thirty theatrical films in a career that spans almost fifty years, much of his music is outstanding, especially the score of Becket.

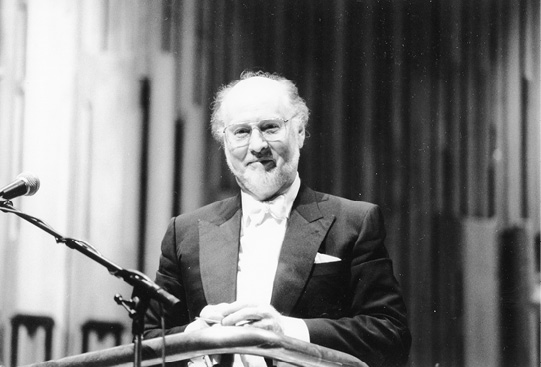

Laurence Rosenthal (1926–)

Born in Detroit in 1926, Rosenthal exhibited musical talent at a very early age. He began piano lessons with his mother at the age of three. As a teenager he appeared as a piano soloist with the Detroit Symphony. He went to the Eastman School of Music, where he studied piano and composition. He then went to Paris, where he studied for two years with Nadia Boulanger, and then went to Salzburg, where he studied conducting at the Mozarteum. While serving in the U.S. Air Force he got his start in film composing by joining the Air Force Documentary Film Squadron. As chief composer for this unit, he worked on several films, including one narrated by Henry Fonda.*

After his stint in the military Rosenthal went to New York, where he started writing incidental music for Broadway plays, including Rashomon, Jean Anou-ihl’s Becket, and John Osborne’s A Patriot for Me. He also wrote ballet music for Meredith Willson’s The Music Man. He composed a ballet score for The Wind in the Mountains, produced by Agnes de Mille’s American Ballet Theater, and composed several symphonic works that were premiered by such noted conductors as Leonard Bernstein and Erich Leinsdorf.

Rosenthal’s first efforts in feature film scoring took place in the 1950s with a pair of low-budget films, Yellowneck (1955) and Naked in the Sun (1957). While neither of these films garnered much attention, Rosenthal started to climb the ladder of success as a film composer with two films adapted from the stage, A Raisin in the Sun (1961) and The Miracle Worker (1962). He also scored the film version of Rod Serling’s teleplay Requiem for a Heavyweight (1962). These three films represented a prelude to the film version of Becket, which became one of 1964’s most acclaimed films, and the winner of several Oscar nominations, including one for its score.