No one likes to be forgotten, especially users of web applications. If an application has any sense of “membership,” meaning that users somehow interact with the application in a personal way, then the application needs to remember the users. You’d hate to have to reintroduce yourself to your family every time you walk through the door at home. You don’t have to because they have this wonderful thing called memory. But web applications don’t remember people automatically—it’s up to a savvy web developer to use the tools at their disposal (PHP and MySQL, maybe?) to build personalized web apps that can actually remember users.

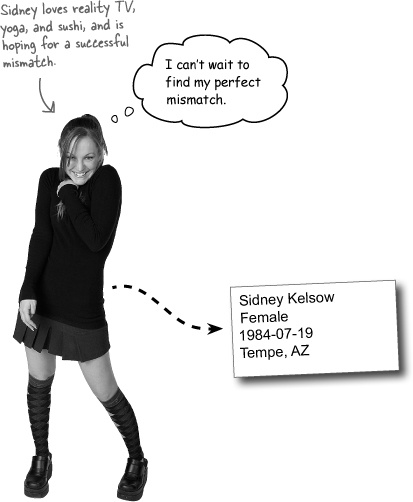

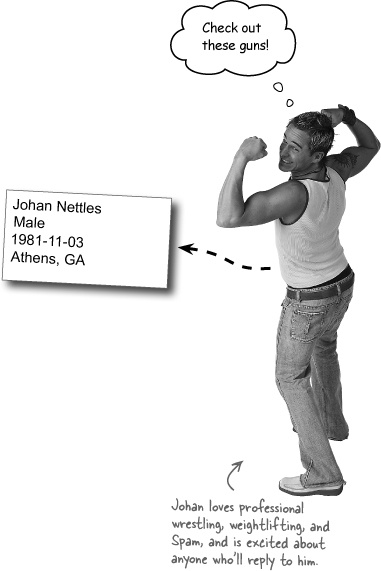

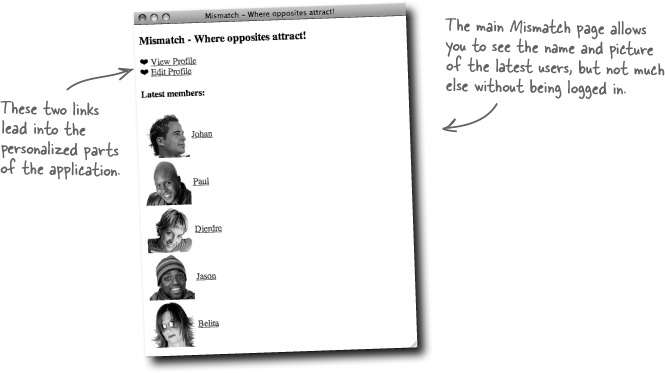

It’s an age-old story: boy meets girl, girl thinks boy is completely nuts, boy thinks girl has issues, but their differences become the attraction, and they end up living happily ever after. This story drives the innovative new dating site, Mis-match.net. Mismatch takes the “opposites attract” theory to heart by mismatching people based on their differences.

Problem is, Mismatch has yet to get off the ground and is in dire need of a web developer to finish building the system. That’s where you come in. Millions of lonely hearts are anxiously awaiting your completion of the application... don’t let them down!

Personal web applications thrive on personal information, which requires users to be able to access an application on a personal level.

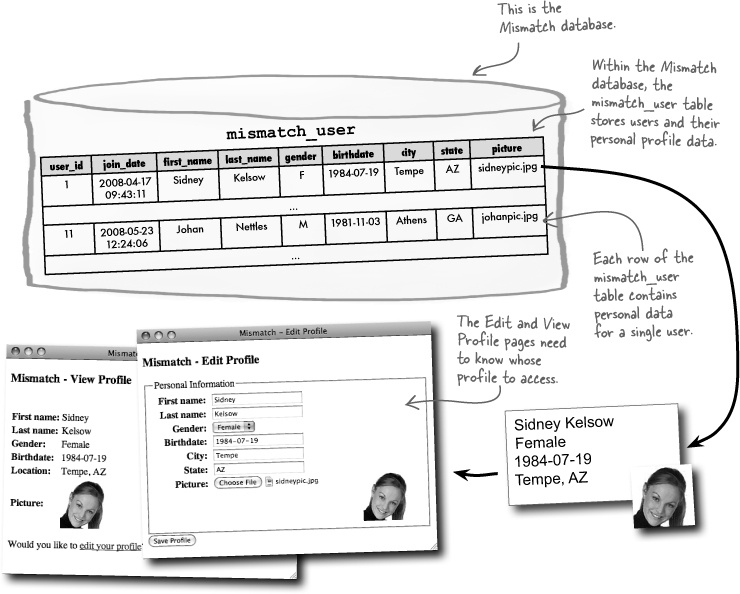

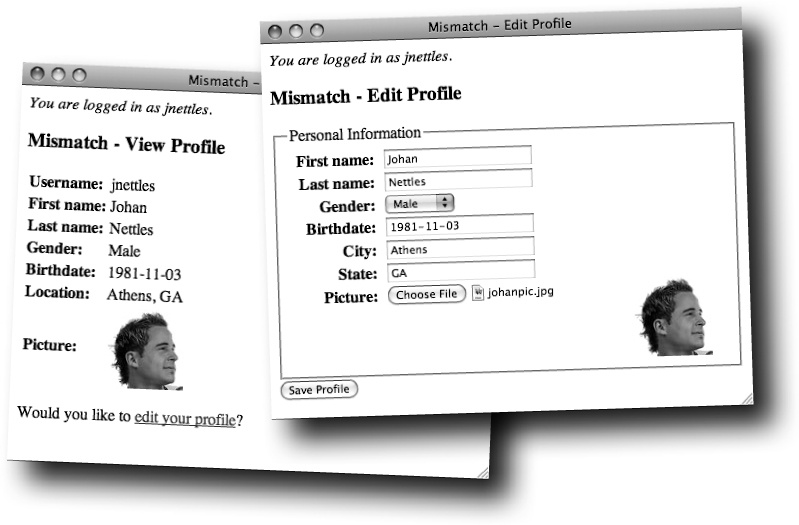

Mismatch users need to be able to interact with the site on a personal level. For one thing, this means they need personal profiles where they enter information about themselves that they can share with other Mismatch users, such as their gender, birthdate, and location.

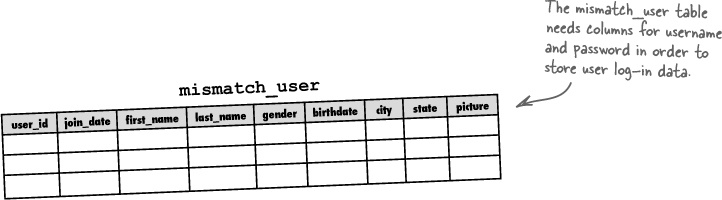

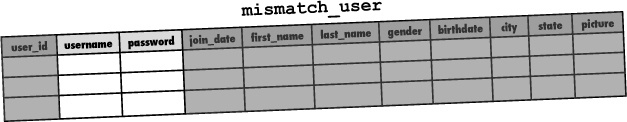

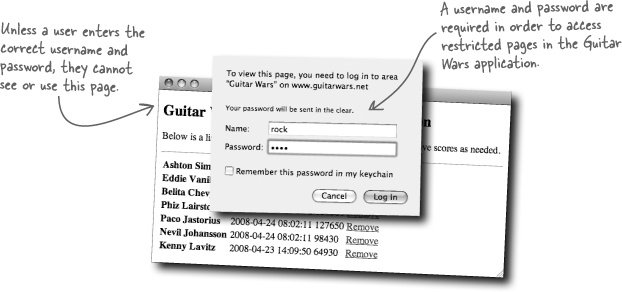

So Mismatch is all about establishing connections through personal data. These connections must take place within a community of users, each of whom is able to interact with the site and manage their own personal data. A table called mismatch_user is used to keep up with Mismatch users and store their personal information.

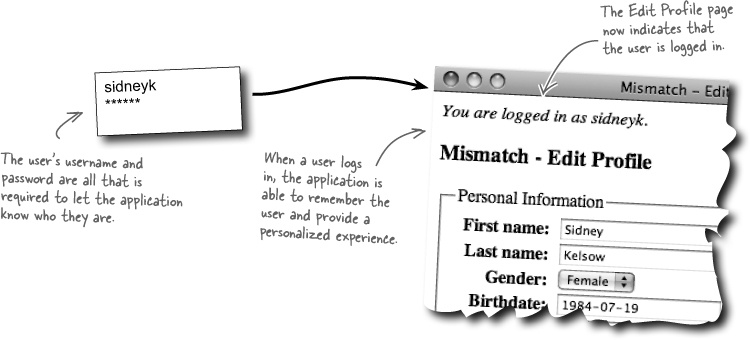

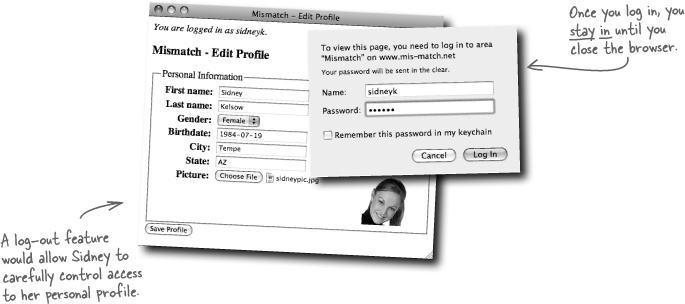

In addition to viewing a user profile, Mismatch users can edit their own personal profiles using the Edit Profile page. But there’s a problem in that the application needs to know which user’s profile to edit. The Edit Profile page somehow needs to keep track of the user who is accessing the page.

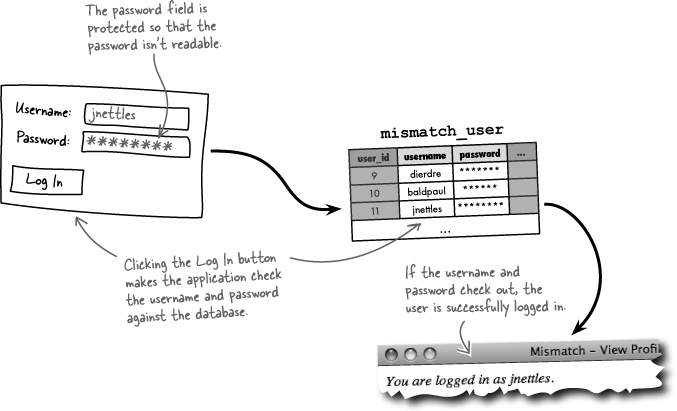

The solution to the Mismatch personal data access problem involves user log-ins, meaning that users need to be able to log into the application. This gives Mismatch the ability to provide access to information that is custom-tailored to each different user. For example, a logged-in user would only have the ability to edit their own profile data, although they might also be able to view other users’ profiles. User log-ins provide the key to personalization for the Mismatch application.

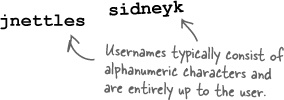

A user log-in typically involves two pieces of information, a username and a password.

User log-ins allow web applications to get personal with users.

The job of the username is to provide each user with a unique name that can be used to identify the user within the system. Users can potentially access and otherwise communicate with each other through their usernames.

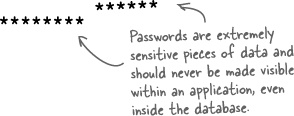

The password is responsible for providing a degree of security when logging in users, which helps to safeguard their personal data. To log in, a user must enter both a username and password.

A username and password allows a user to log in to the Mismatch application and access personal data, such as editing their profile.

Adding user log-in support to Mismatch is no small feat, and it’s important to work out exactly what is involved before writing code and running database queries. We know there is an existing table that stores users, so the first thing is to alter it to store log-in data. We’ll also need a way for users to enter their log-in data, and this somehow needs to integrate with the rest of the Mismatch application so that pages such as the Edit Profile page are only accessible after a successful log-in. Here are the log-in development steps we’ve worked out so far:

|

Before going any further, take a moment to tinker with the Mismatch application and get a feel for how it works.

Download all of the code for the Mismatch application from the Head First Labs web site at www.headfirstlabs.com/books/hfphp. Post all of the code to your web server except for the .sql files, which contain SQL statements that build the necessary Mismatch tables. Make sure to run the statement in each of the .sql files in a MySQL tool so that you have the initial Mismatch tables to get started with.

When all that’s done, navigate to the index.php page in your web browser, and check out the application. Keep in mind that the View Profile and Edit Profile pages are initially broken since they are entirely dependent upon user log-ins, which we’re in the midst of building.

OK, back to the construction. The mismatch_user table already does a good job of holding profile information for each user, but it’s lacking when it comes to user log-in information. More specifically, the table is missing columns for storing a username and password for each user.

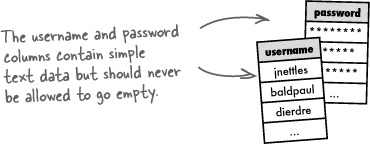

Username and password data both consist of pure text, so it’s possible to use the familiar VARCHAR MySQL data type for the new username and password columns. However, unlike some other user profile data, the username and password shouldn’t ever be allowed to remain empty (NULL).

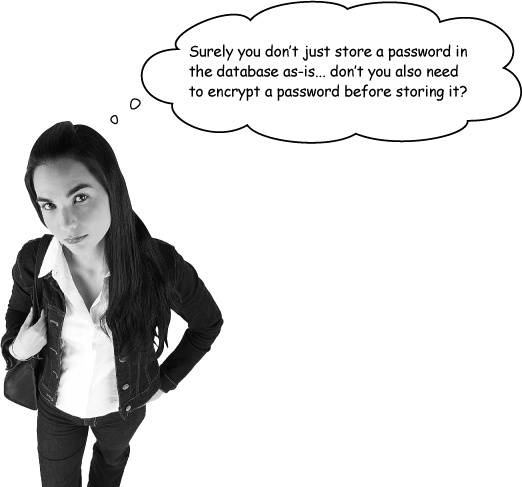

Good point... passwords require encryption.

Encryption in Mismatch involves converting a password into an unrecognizable format when stored in the database. Any application with user log-in support must encrypt passwords so that users can feel confident that their passwords are safe and secure. Exposing a user’s password even within the database itself is not acceptable. So we need a means of encrypting a password before inserting it into the mismatch_user table. Problem is, encryption won’t help us much if we don’t have a way for users to actually enter a username and password to log in...

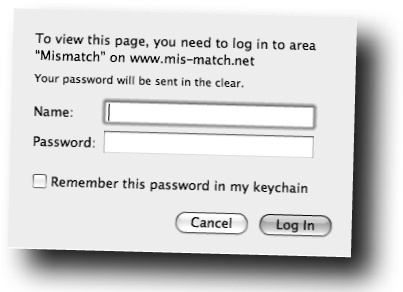

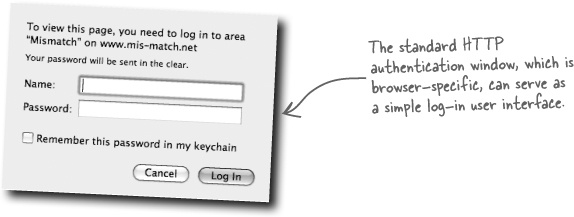

With the database altered to hold user log-in data, we still need a way for users to enter the data and actually log in to the application. This log-in user interface needs to consist of text edit fields for the username and password, as well as a button for carrying out the log-in.

An application log-in requires a user interface for entering the username and password.

Relax

If you’re worried about how users will be able to log in when we haven’t assigned them user names and passwords yet... don’t sweat it.

We’ll get to creating user names and passwords for users in just a bit. For now it’s important to lay the groundwork for log-ins, even if we still have more tasks ahead before it all comes together.

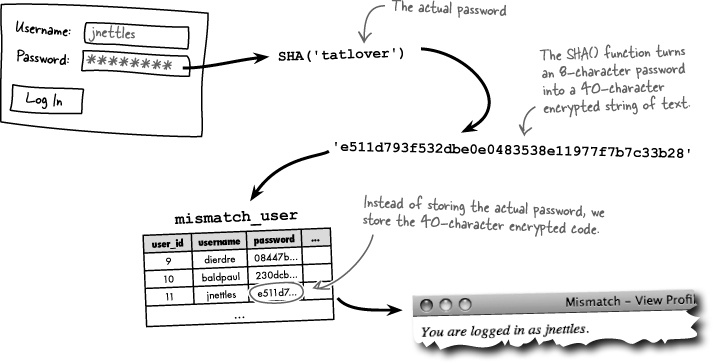

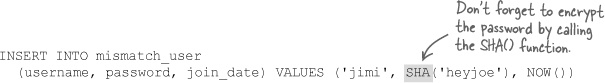

The log-in user interface is pretty straightforward, but we didn’t address the need to encrypt the log-in password. MySQL offers a function called SHA() that applies an encryption algorithm to a string of text. The result is an encrypted string that is exactly 40 hexadecimal characters long, regardless of the original password length. So the function actually generates a 40-character code that uniquely represents the password.

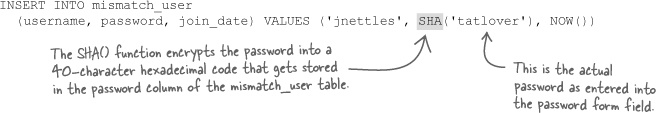

Since SHA() is a MySQL function, not a PHP function, you call it as part of the query that inserts a password into a table. For example, this code inserts a new user into the mismatch_user table, making sure to encrypt the password with SHA() along the way.

The MySQL SHA() function encrypts a piece of text into a unique 40-character code.

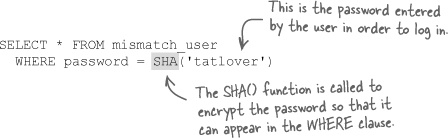

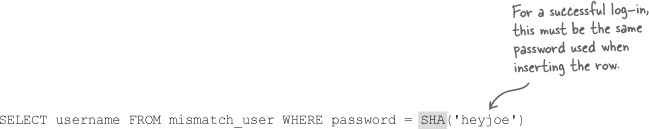

The same SHA() function works on the other end of the log-in equation by checking to see that the password entered by the user matches up with the encrypted password stored in the database.

Once you’ve encrypted a piece of information, the natural instinct is to think in terms of decrypting it at some point. But the SHA() function is a one-way encryption with no way back. This is to preserve the security of the encrypted data—even if someone hacked into your database and stole all the passwords, they wouldn’t be able to decrypt them. So how is it possible to log in a user if you can’t decrypt their password?

You don’t need to know a user’s original password to know if they’ve entered the password correctly at log-in. This is because SHA() generates the same 40-character code as long as you provide it with the same string of text. So you can just encrypt the log-in password entered by the user and compare it to the value in the password column of the mismatch_user table. This can be accomplished with a single SQL query that attempts to select a matching user row based on a password.

The SHA() function provides one-way encryption—you can’t decrypt data that has been encrypted.

This SELECT query selects all rows in the mismatch_user table whose password column matches the entered password, 'tatlover' in this case. Since we’re comparing encrypted versions of the password, it isn’t necessary to know the original password. A query to actually log in a user would use SHA(), but it would also need to SELECT on the user ID, as we see in just a moment.

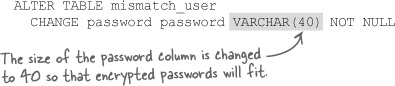

The SHA() function presents a problem for Mismatch since encrypted passwords end up being 40 characters long, but our newly created password column is only 16 characters long. An ALTER is in order to expand the password column for storing encrypted passwords.

Yes! HTTP authentication will certainly work as a simple user log-in system.

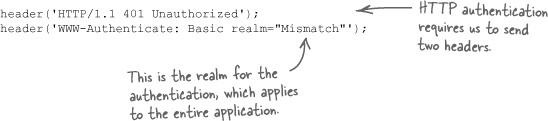

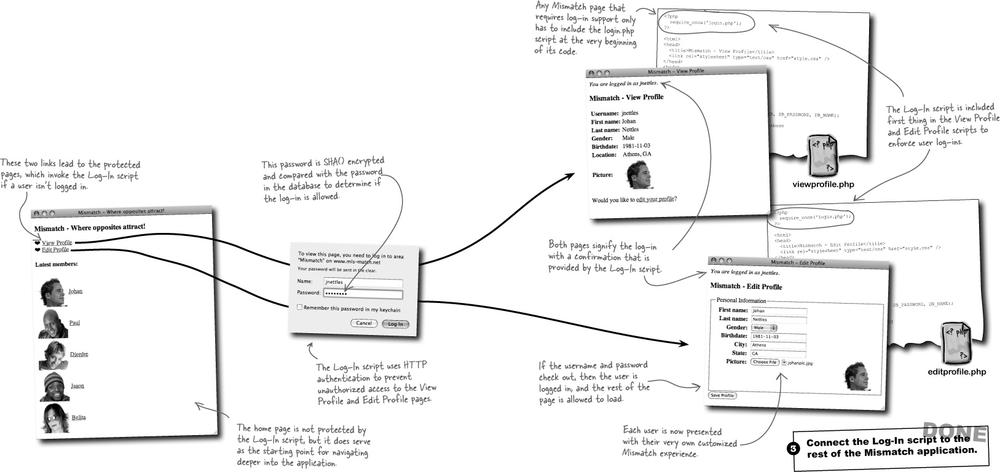

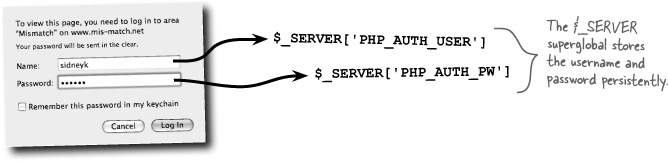

If you recall from the Guitar Wars high score application in the last chapter, HTTP authentication was used to restrict access to certain parts of an application by prompting the user for a username and password. That’s roughly the same functionality required by Mismatch, except that now we have an entire database of possible username/password combinations, as opposed to one application-wide username and password. Mismatch users could use the same HTTP authentication window; however, they’ll just be entering their own personal username and password.

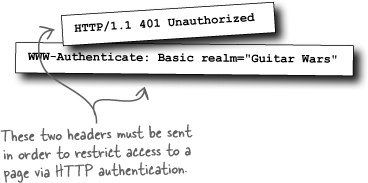

As Guitar Wars illustrated, two headers must be sent in order to restrict access to a page via an HTTP authentication window. These headers result in the user being prompted for a username and password in order to gain access to the Admin page of Guitar Wars.

Sending the headers for HTTP authentication amounts to two lines of PHP code—a call to the header() function for each header being sent.

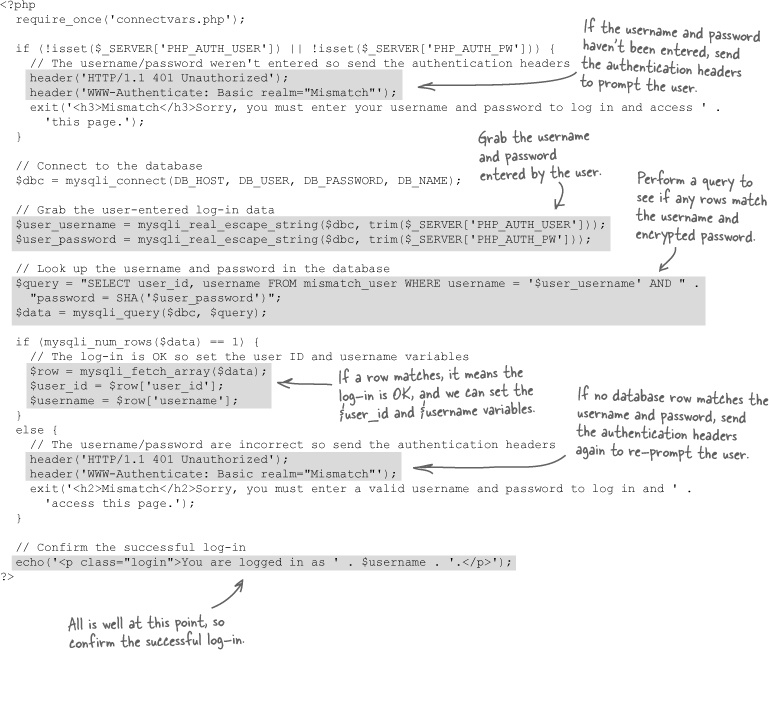

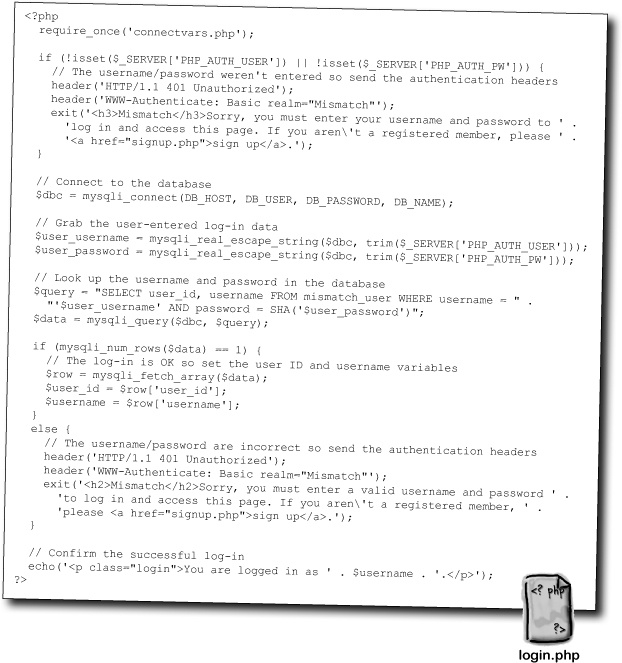

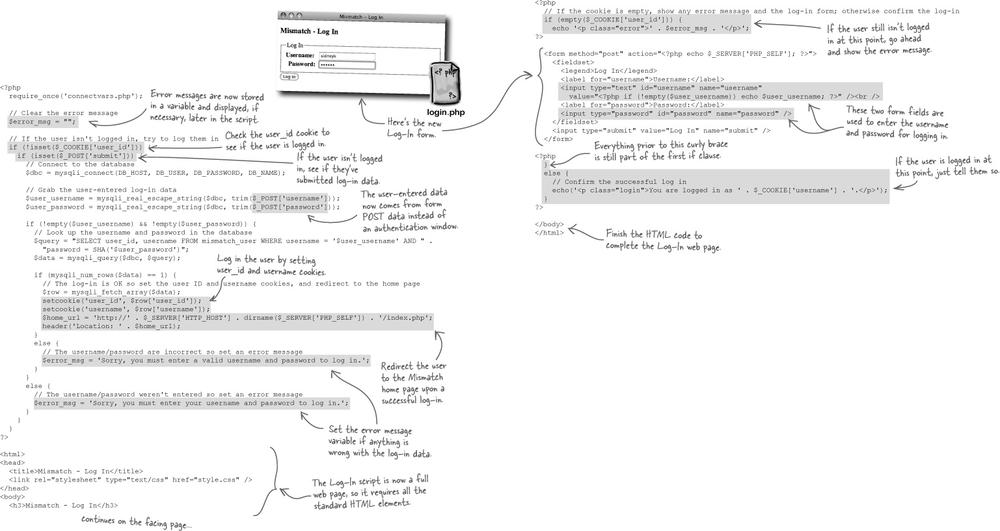

The Log-In script (login.php) is responsible for requesting a username and password from the user using HTTP authentication headers, grabbing the username and password values from the $_SERVER superglobal, and then checking them against the mismatch_user database before providing access to a restricted page.

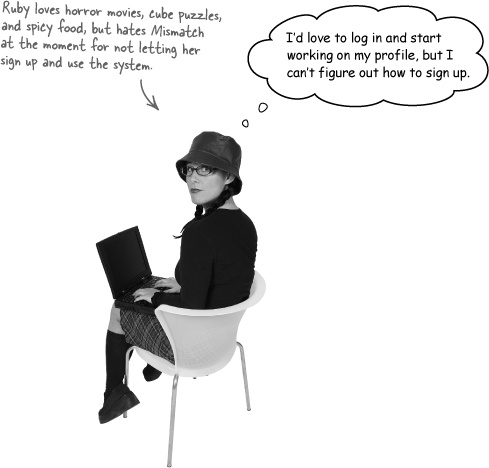

New Mismatch users need a way to sign up.

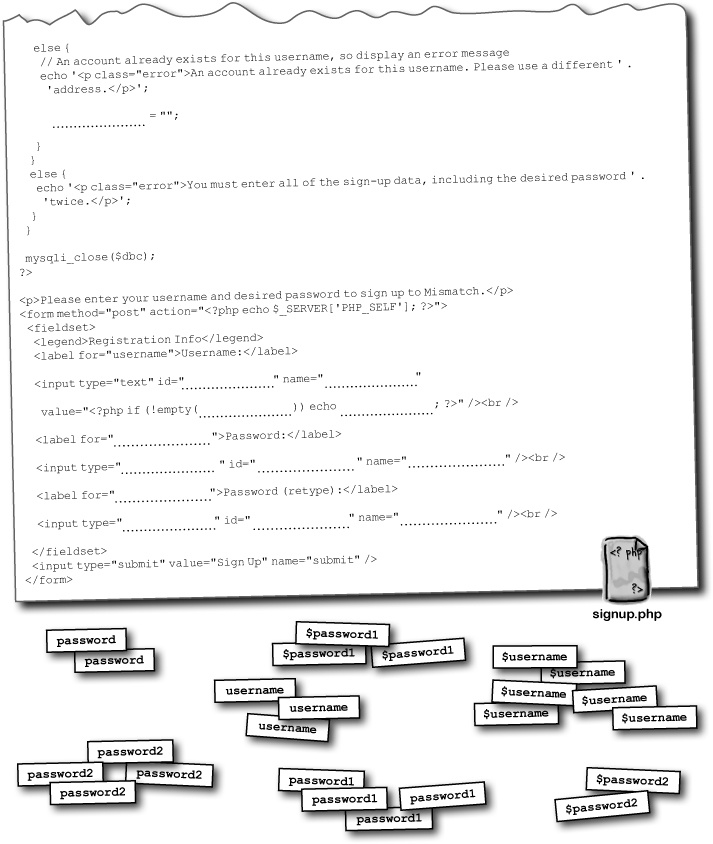

The new Mismatch Log-In script does a good job of using HTTP authentication to allow users to log in. Problem is, users don’t have a way to sign up—logging in is a problem when you haven’t even created a username or password yet. Mismatch needs a Sign-Up form that allows new users to join the site by creating a new username and password.

Username? | |

Password? | |

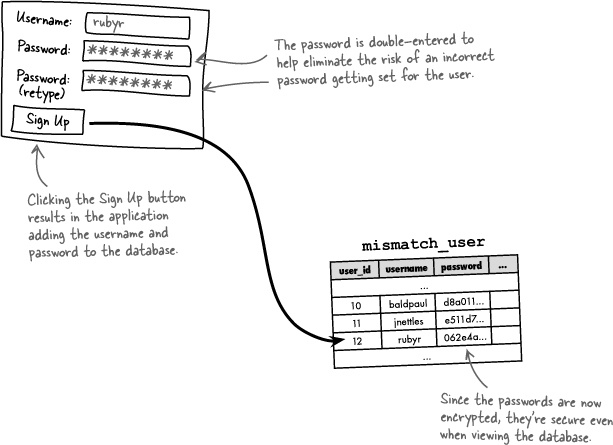

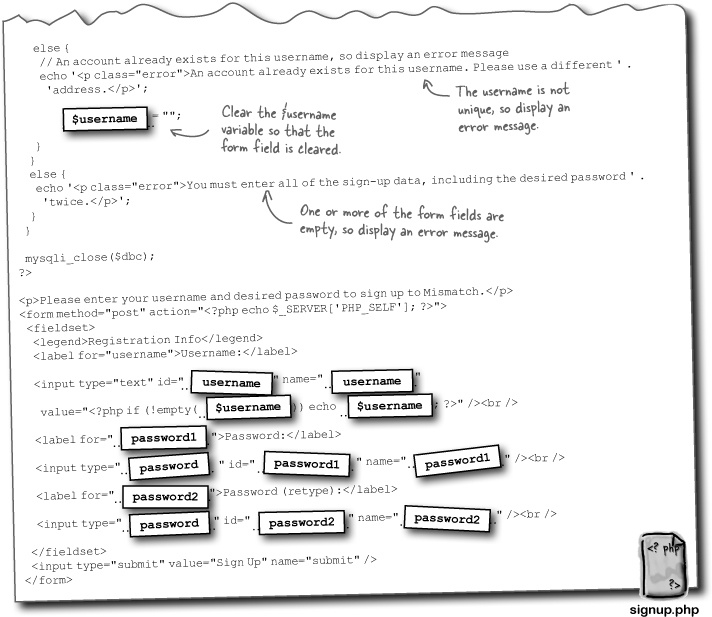

What does this new Sign-Up form look like? We know it needs to allow the user to enter their desired username and password... anything else? Since the user is establishing their password with the new Sign-Up form, and passwords in web forms are typically masked with asterisks for security purposes, it’s a good idea to have two password form fields. So the user enters the password twice, just to make sure there wasn’t a typo.

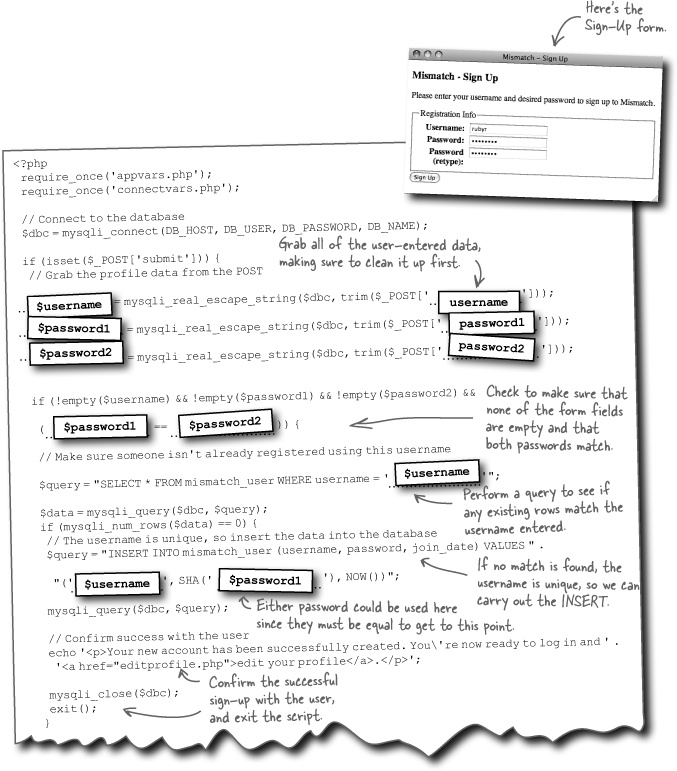

So the job of the Sign-Up page is to retrieve the username and password from the user, make sure the username isn’t already used by someone else, and then add the new user to the mismatch_user database.

One potential problem with the Sign-Up script involves the user attempting to sign up for a username that already exists. The script needs to be smart enough to catch this problem and force the user to try a different username. So the job of the Sign-Up page is to retrieve the username and password from the user, make sure the username isn’t already used by someone else, and then add the new user to the mismatch_user database.

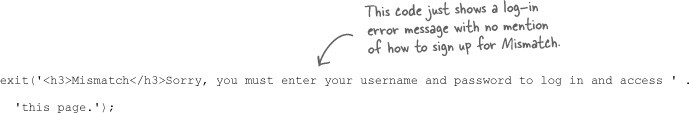

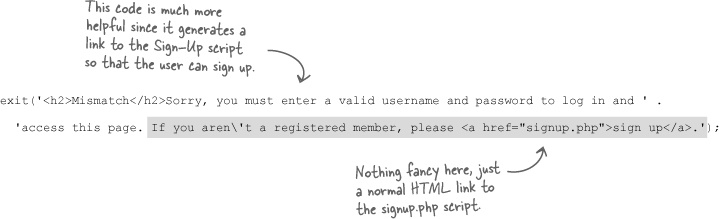

We have a Sign-Up script, but how do users get to it? We need to let users know how to sign up. One option is to put a “Sign Up” link on the main Mismatch page. That’s not a bad idea, but we would ideally need to be able to turn it on and off based on whether a user is logged in. Another possibility is to just show a “Sign Up” link as part of the Log-In script.

When a new user clicks the “View Profile” or “Edit Profile” links on the main page, for example, they’ll be prompted for a username and password by the Log-In script. Since they don’t yet have a username or password, they will likely click Cancel to bail out of the log-in. That’s our chance to display a link to the Sign-Up script by tweaking the log-in failure message displayed by the Log-In script so that it provides a link to signup.php.

Here’s the original log-in failure code:

This code actually appears in two different places in the Log-In script: when no username or password are entered and when they are entered incorrectly. It’s probably a good idea to go ahead and provide a “Sign Up” link in both places. Here’s what the new code might look like:

Community web sites must allow users to log out so that others can’t access their personal data from a shared computer.

Allowing users to log out might sound simple enough, but it presents a pretty big problem with HTTP authentication. The problem is that HTTP authentication is intended to be carried out once for a given page or collection of pages—it’s only reset when the browser is shut down. In other words, a user is never “logged out” of an HTTP authenticated web page until the browser is shut down or the user manually clears the HTTP authenticated session. The latter option is easier to carry out in some browsers (Firefox, for example) than others (Safari).

Even though HTTP authentication presents a handy and simple way to support user log-ins in the Mismatch application, it doesn’t provide any control over logging a user out. We need to be able to both remember users and also allow them to log out whenever they want.

The problem originally solved by HTTP authentication is twofold: there is the issue of limiting access to certain pages, and there is the issue of remembering that the user entered information about themselves. The second problem is the tricky one because it involves an application remembering who the user is across multiple pages (scripts). Mismatch accomplishes this feat by checking the username and password stored in the $_SERVER superglobal. So we took advantage of the fact that PHP stores away the HTTP authentication username and password in a superglobal that persists across multiple pages.

HTTP authentication stores data persistently on the client but doesn’t allow you to delete it when you’re done.

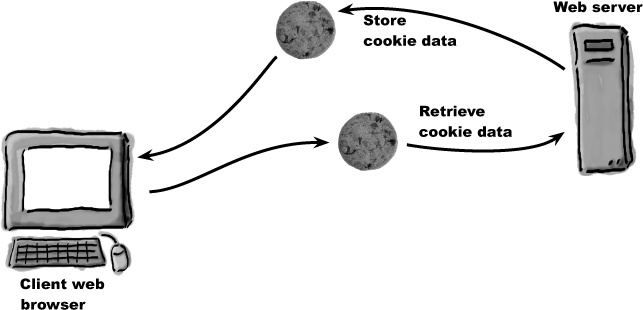

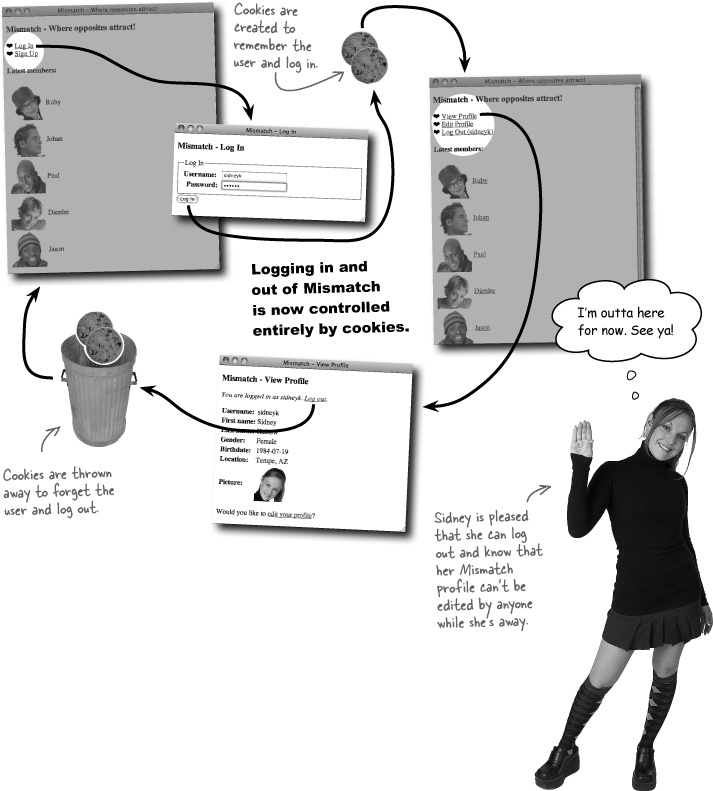

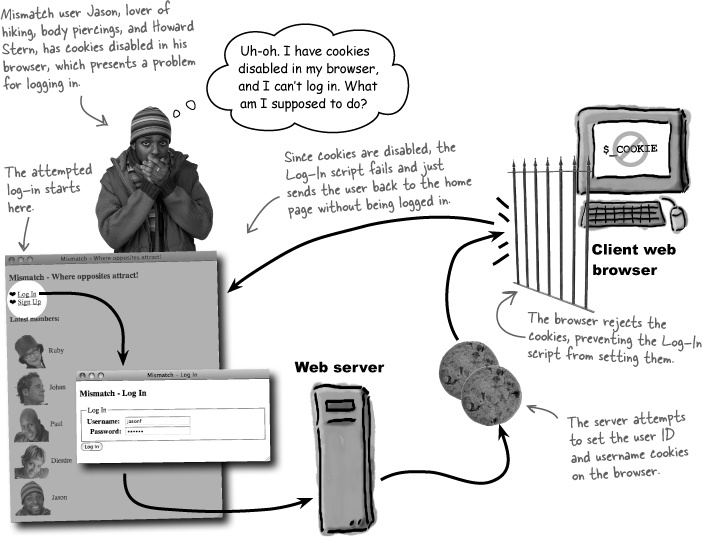

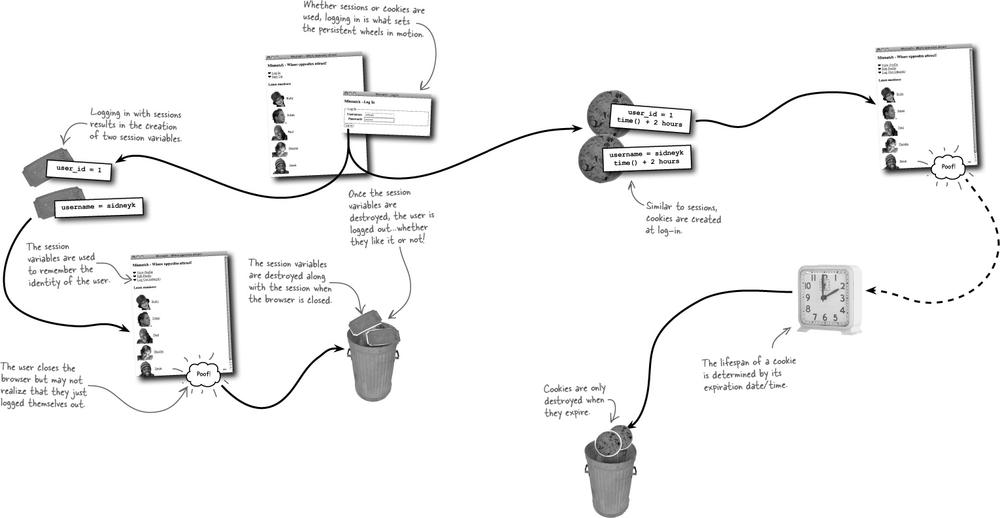

But we don’t have the luxury of HTTP authentication anymore because it can’t support log-outs. So we need to look elsewhere for user persistence across multiple pages. A possible solution lies in cookies, which are pieces of data stored by the browser on the user’s computer. Cookies are a lot like PHP variables except that cookies hang around after you close the browser, turn off your computer, etc. More importantly, cookies can be deleted, meaning that you can eliminate them when you’re finished storing data, such as when a user indicates they want to log out.

Cookies allow you to persistently store small pieces of data on the client that can outlive any single script... and can be deleted at will!

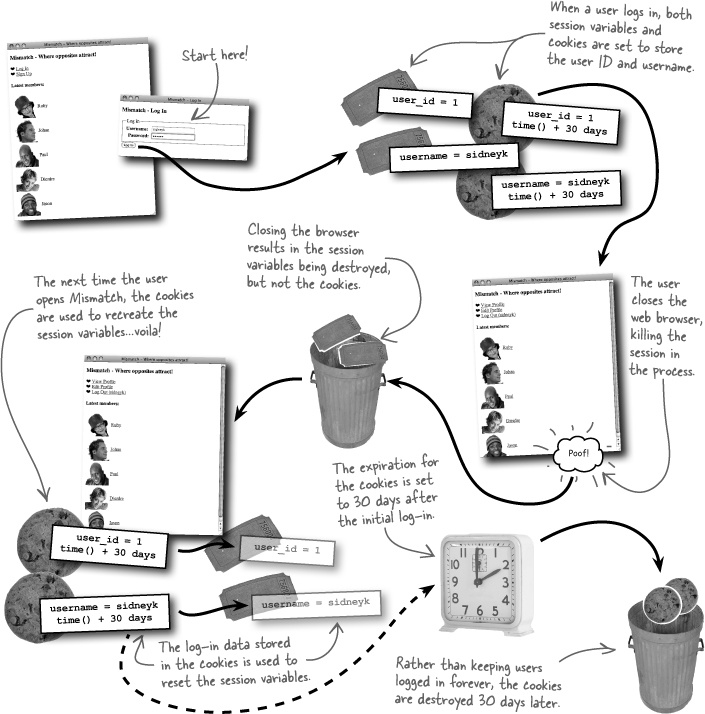

Cookie data is stored on the user’s computer by their web browser. You have access to the cookie data from PHP code, and the cookie is capable of persisting across not only multiple pages (scripts), but even multiple browser sessions. So a user closing their browser won’t automatically log them out of Mismatch. This isn’t a problem for us because we can delete a cookie at any time from script code, making it possible to offer a log-out feature. We can give users total control over when they log out.

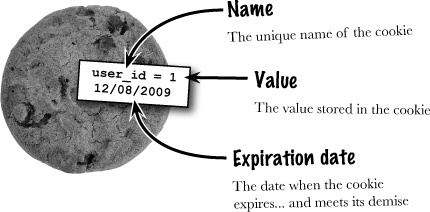

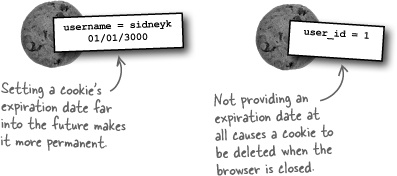

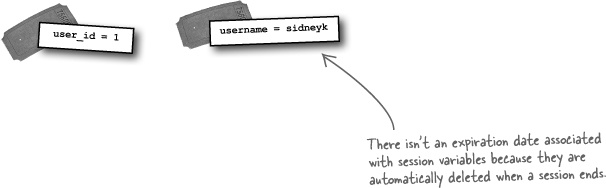

A cookie stores a single piece of data under a unique name, much like a variable in PHP. Unlike a variable, a cookie can have an expiration date. When this expiration date arrives, the cookie is destroyed. So cookies aren’t exactly immortal—they just live longer than PHP variables. You can create a cookie without an expiration date, in which case it acts just like a PHP variable—it gets destroyed when the browser closes.

Cookies allow you to store a string of text under a certain name, kind of like a PHP text variable. It’s the fact that cookies outlive normal script data that makes them so powerful, especially in situations where an application consists of multiple pages that need to remember a few pieces of data, such as log-in information.

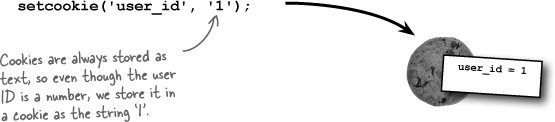

So Mismatch can mimic the persistence provided by the $_SERVER superglobal by setting two cookies—one for the username and one for the password. Although we really don’t need to keep the password around, it might be more helpful to store away the user ID instead.

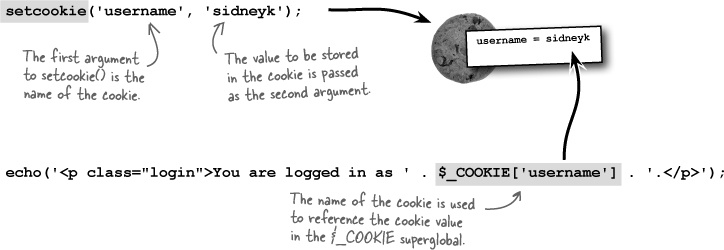

PHP provides access to cookies through a function called setcookie() and a superglobal called $_COOKIE. The setcookie() function is used to set the value and optional expiration date of a cookie, and the $_COOKIE superglobal is used to retrieve the value of a cookie.

The PHP setcookie() function allows you to store data in cookies.

The power of setting a cookie is that the cookie data persists across multiple scripts, so we can remember the username without having to prompt the user to log in every time they move from one page to another within the application. But don’t forget, we also need to store away the user’s ID in a cookie since it serves as a primary key for database queries.

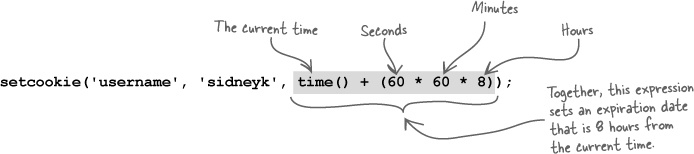

The setcookie() function also accepts an optional third argument that sets the expiration date of the cookie, which is the date upon which the cookie is automatically deleted. If you don’t specify an expiration date, as in the above example, the cookie automatically expires when the browser is closed.

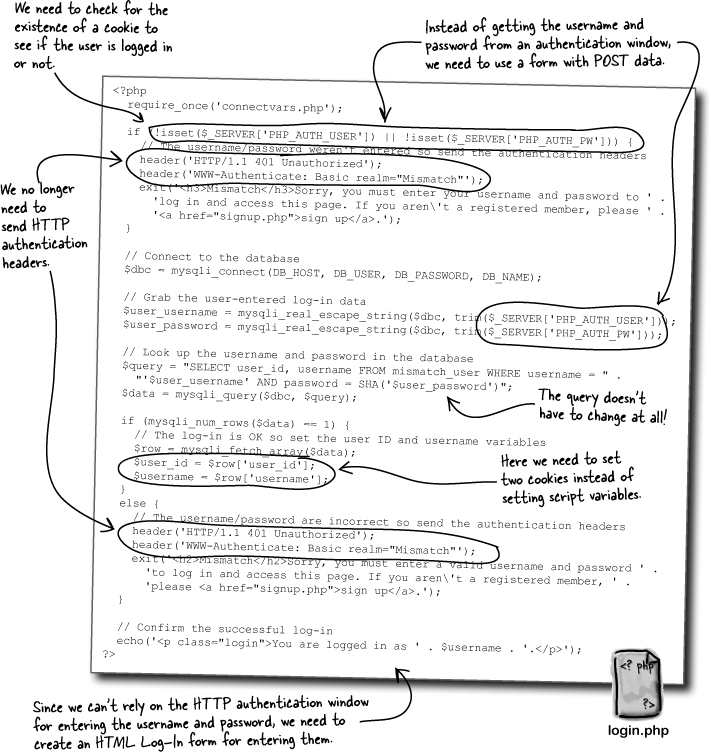

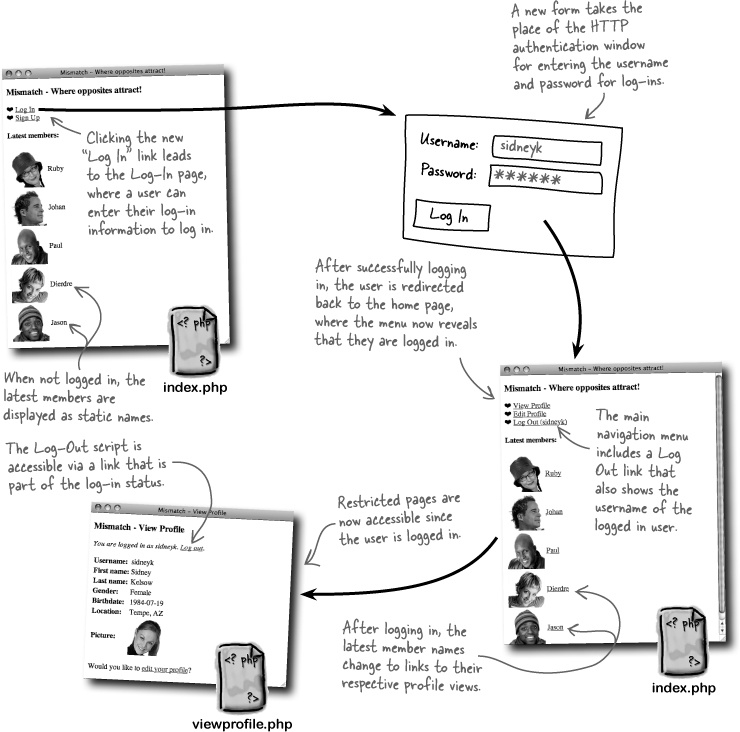

Using cookies instead of HTTP authentication for Mismatch log-ins involves more than just rethinking the storage of user data. What about the log-in user interface? The cookie-powered log-in must provide its own form since it can’t rely on the authentication window for entering a username and password. Not only do we have to build this form, but we need to think through how it changes the flow of the application as users log in and access other pages.

The new version of the Log-In script that relies on cookies for log-in persistence is a bit more complex than its predecessor since it must provide its own form for entering the username and password. But it’s more powerful in that it provides log-out functionality.

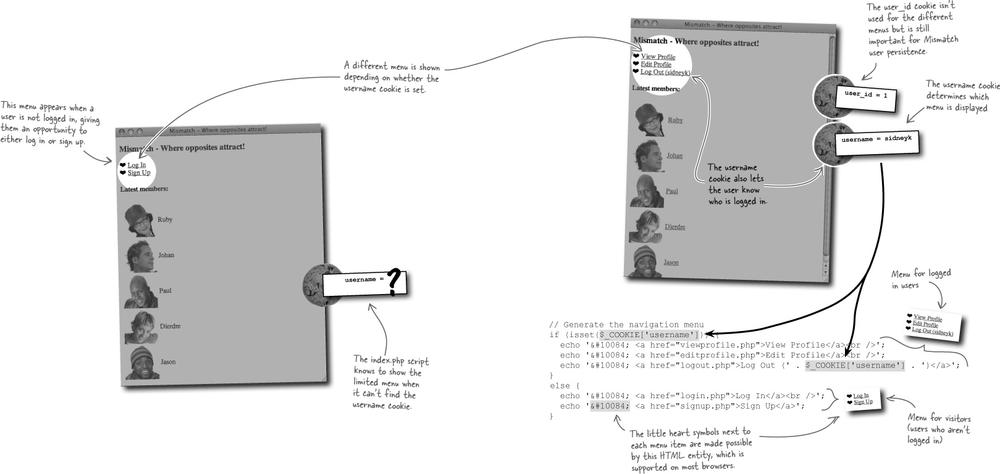

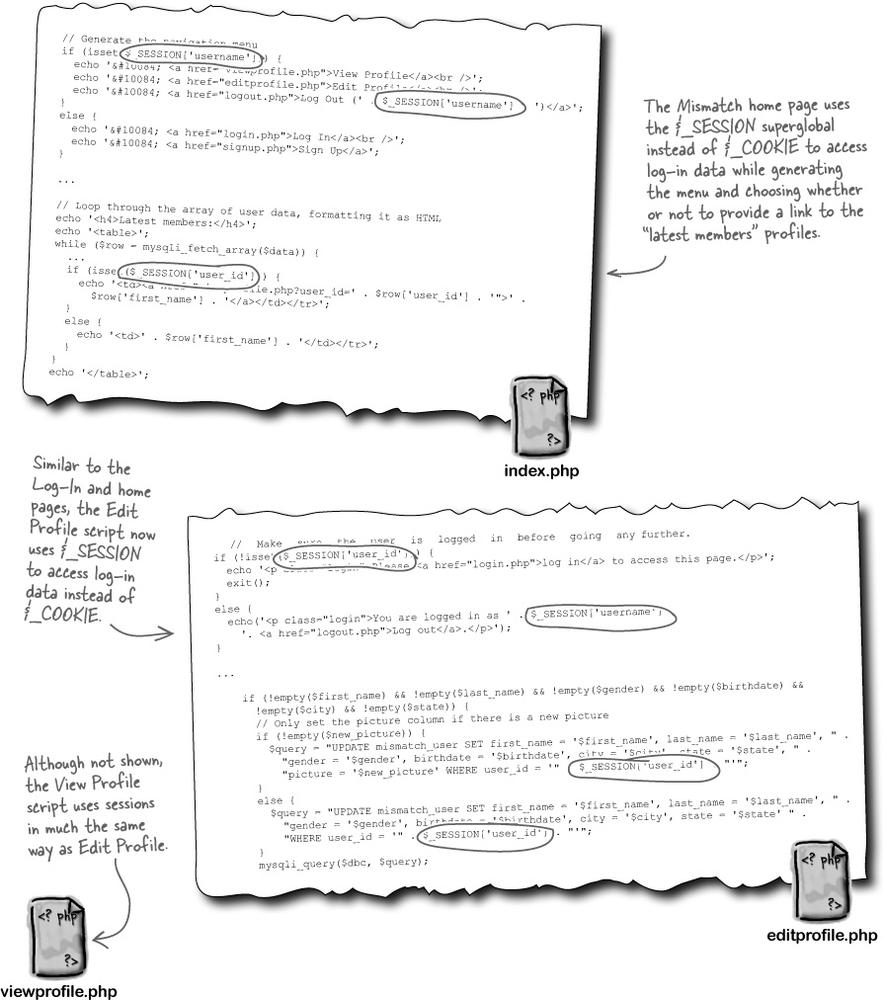

The new Log-In script changes the flow of the Mismatch application, requiring a simple menu that appears on the home page (index.php). This menu is important because it provides access to the different major parts of the application, currently the View Profile and Edit Profile pages, as well as the ability for users to log in, sign up, and log out depending on their current log-in state. The fact that the menu changes based on the user’s log-in state is significant and is ultimately what gives the menu its power and usefulness.

The menu is generated by PHP code within the index.php script, and this code uses the $_COOKIE superglobal to look up the username cookie and see if the user is logged in or not. The user ID cookie could have also been used, but the username is actually displayed in the menu, so it makes more sense to check for it instead.

We really need to let users log out.

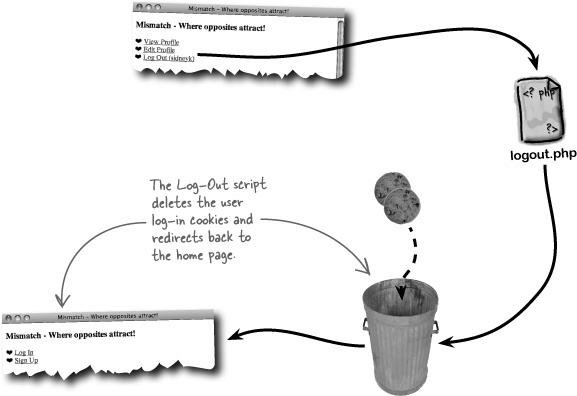

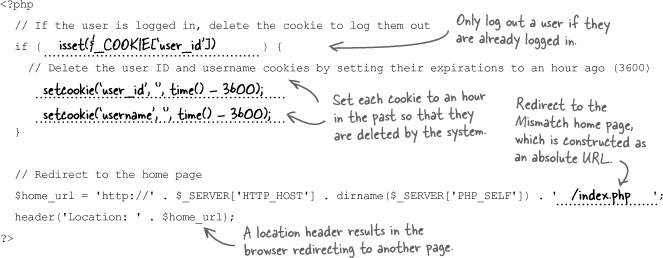

Cookies have made logging into Mismatch and navigating the site a bit cleaner, but the whole point of switching from HTTP authentication to cookies was to allow users to log out. We need a new Log-Out script that deletes the two cookies (user ID and username) so that the user no longer has access to the application. This will prevent someone from getting on the same computer later and accessing a user’s private profile data.

Since there is no user interface component involved in actually logging out a user, it’s sufficient to just redirect them back to the home page after logging them out.

Logging out a user involves deleting the two cookies that keep track of the user. This is done by calling the setcookie() function, and passing an expiration date that causes the cookies to get deleted at that time.

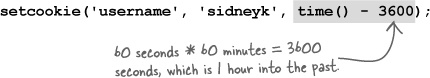

This code sets an expiration date 8 hours into the future, which means the cookie will be automatically deleted in 8 hours. But we want to delete a cookie immediately, which requires setting the expiration date to a time in the past. The amount of time into the past isn’t terribly important—just pick an arbitrary amount of time, such as an hour, and subtract it from the current time.

To delete a cookie, just set its expiration date to a time in the past.

Yes, but web applications should be as accessible to as many people as possible.

Some people just aren’t comfortable using cookies, so they opt for the added security of having them disabled. Knowing this, it’s worth trying to accommodate users who can’t rely on cookies to log in. But there’s more. It turns out that there’s another option that uses the server to store log-in data, as opposed to the client. And since our scripts are already running on the server, it only makes sense to store log-in data there as well.

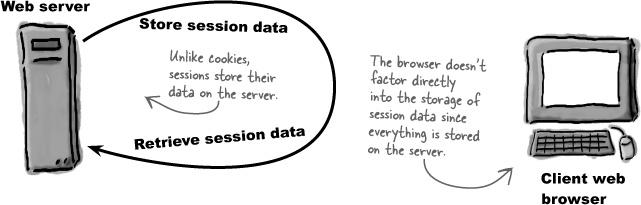

Cookies are powerful little guys, but they do have their limitations, such as being subject to limitations beyond your control. But what if we didn’t have to depend on the browser? What if we could store data directly on the server? Sessions do just that, and they allow you to store away individual pieces of information just like with cookies, but the data gets stored on the server instead of the client. This puts session data outside of the browser limitations of cookies.

Sessions allow you to persistently store small pieces of data on the server, independently of the client.

Sessions store data in session variables, which are logically equivalent to cookies on the server. When you place data in a session variable using PHP code, it is stored on the server. You can then access the data in the session variable from PHP code, and it remains persistent across multiple pages (scripts). Like with cookies, you can delete a session variable at any time, making it possible to continue to offer a log-out feature with session-based code.

Since session data is stored on the server, it is more secure and more reliable than data stored in cookies.

Note

A user can’t manually delete session data using their browser, which can be a problem with cookies.

Surely there’s a catch, right? Sort of. Unlike cookies, sessions don’t offer as much control over how long a session variable stores data. Session variables are automatically destroyed as soon as a session ends, which usually coincides with the user shutting down the browser. So even though session variables aren’t stored on the browser, they are indirectly affected by the browser since they get deleted when a browser session ends.

Sessions are called sessions for a reason—they have a very clear start and finish. Data associated with a session lives and dies according to the lifespan of the session, which you control through PHP code. The only situation where you don’t have control of the session life cycle is when the user closes the browser, which results in a session ending, whether you like it or not.

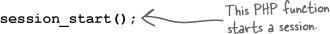

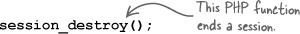

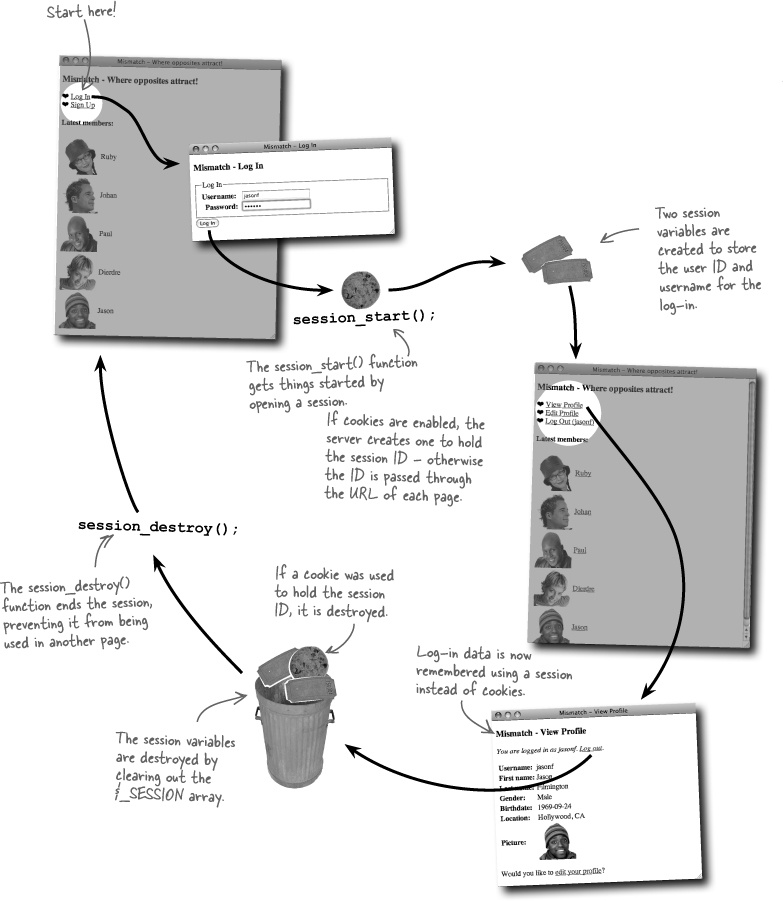

You must tell a session when you’re ready to start it up by calling the session_start() PHP function.

The PHP session_start() function starts a session and allows you to begin storing data in session variables.

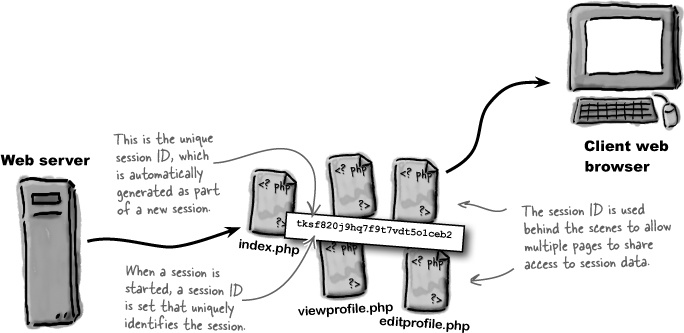

Calling the session_start() function doesn’t set any data—its job is to get the session up and running. The session is identified internally by a unique session identifier, which you typically don’t have to concern yourself with. This ID is used by the web browser to associate a session with multiple pages.

The session ID isn’t destroyed until the session is closed, which happens either when the browser is closed or when you call the session_destroy() function.

If you close a session yourself with this function, it doesn’t automatically destroy any session variables you’ve stored. Let’s take a closer look at how sessions store data to uncover why this is so.

The session_destroy() function closes a session.

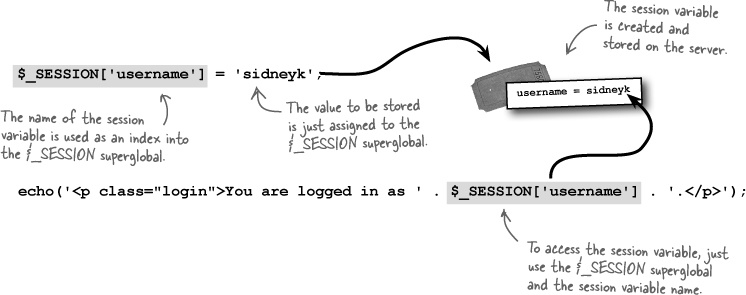

The cool thing about sessions is that they’re very similar to cookies in terms of how you use them. Once you’ve started a session with a call to session_start(), you can begin setting session variables, such as Mismatch log-in data, with the $_SESSION superglobal.

Unlike cookies, session variables don’t require any kind of special function to set them—you just assign a value to the $_SESSION superglobal, making sure to use the session variable name as the array index.

What about deleting session variables? Destroying a session via session_destroy() doesn’t actually destroy session variables, so you must manually delete your session variables if you want them to be killed prior to the user shutting down the browser (log-outs!). A quick and effective way to destroy all of the variables for a session is to set the $_SESSION superglobal to an empty array.

Session variables are not automatically deleted when a session is destroyed.

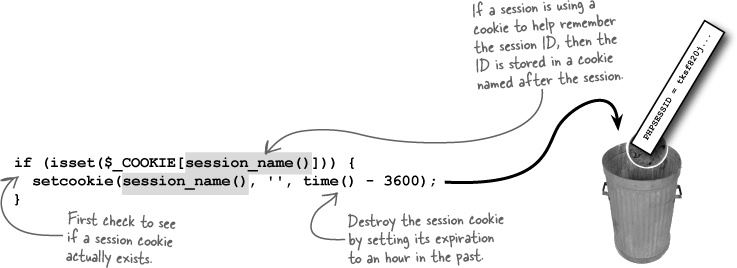

But we’re not quite done. Sessions can actually use cookies behind the scenes. If the browser allows cookies, a session may possibly set a cookie that temporarily stores the session ID. So to fully close a session via PHP code, you must also delete any cookie that might have been automatically created to store the session ID on the browser. Like any other cookie, you destroy this cookie by setting its expiration to some time in the past. All you need to know is the name of the cookie, which can be found using the session_name() function.

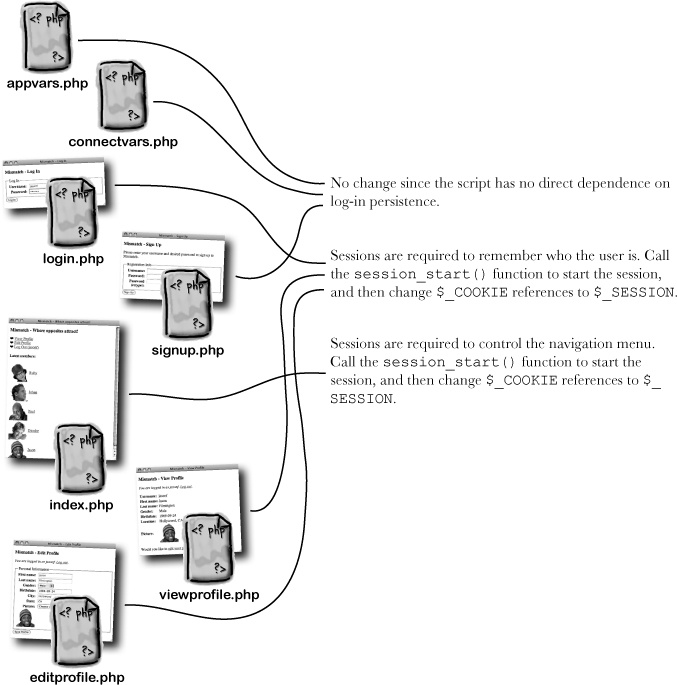

Reworking the Mismatch application to use a session to store log-in data isn’t as dramatic as it may sound. In fact, the flow of the application remains generally the same—you just have to take care of a little extra bookkeeping involved in starting the session, destroying the session, and then cleaning up after the session.

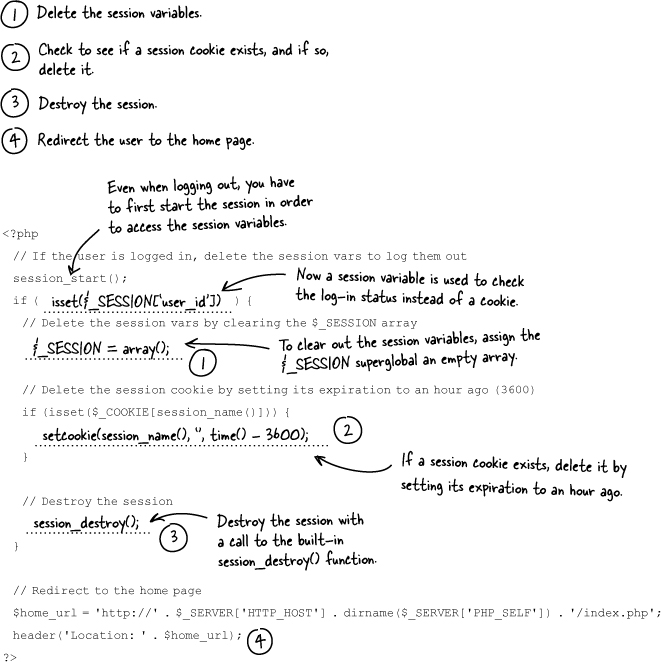

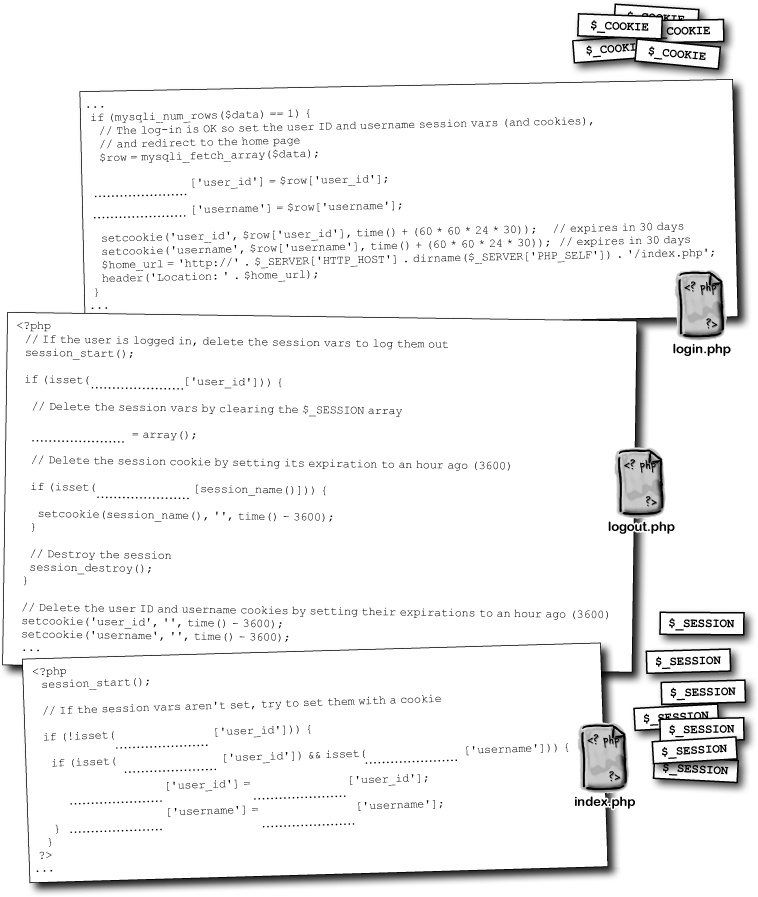

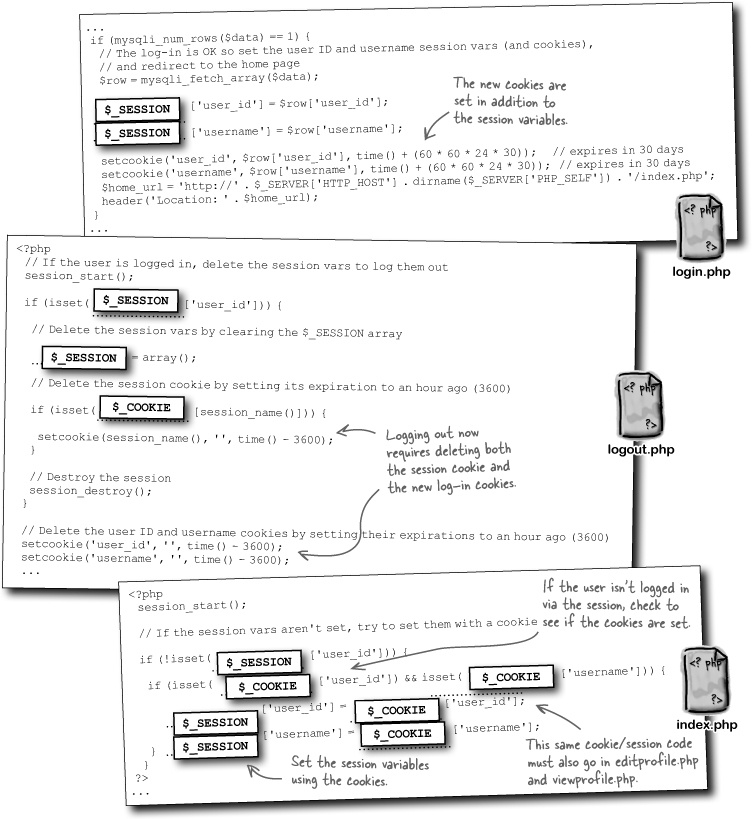

Logging a user out of Mismatch requires a little more work with sessions than the previous version with its pure usage of cookies. These steps must be taken to successfully log a user out of Mismatch using sessions.

Delete the session variables.

Check to see if a session cookie exists, and if so, delete it.

Destroy the session.

Redirect the user to the home page.

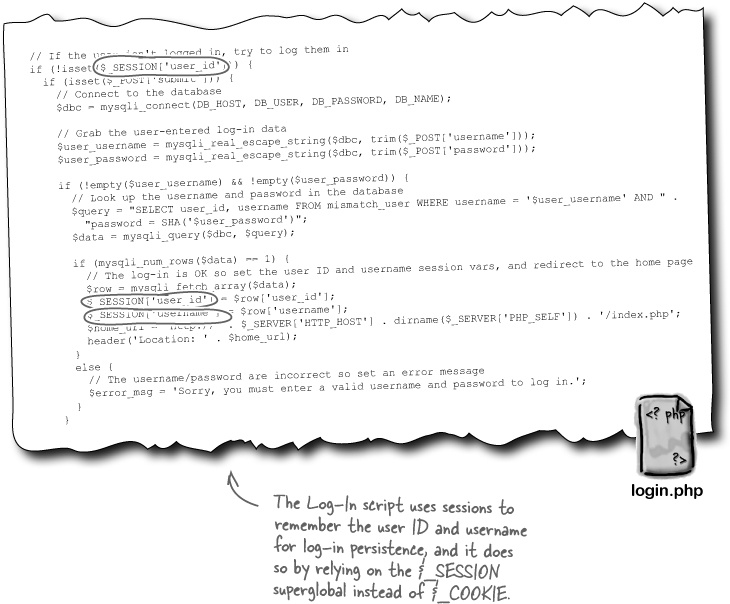

Even though the different parts of Mismatch affected by sessions use them to accomplish different things, the scripts ultimately require similar changes in making the migration from cookies to sessions. For one, they all must call the session_start() function to get rolling with sessions initially. Beyond that, all of the changes involve moving from the $_COOKIE superglobal to the $_SESSION superglobal, which is responsible for storing session variables.

Watch it!

Sessions without cookies may not work if your PHP settings in php.ini aren’t configured properly on the server.

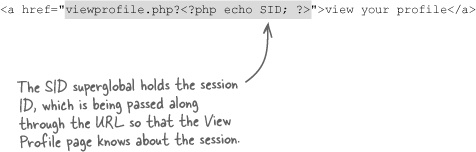

In order for sessions to work with cookies disabled, there needs to be another mechanism for passing the session ID among different pages. This mechanism involves appending the session ID to the URL of each page, which takes place automatically if the session.use_trans_id setting is set to 1 (true) in the php.ini file on the server. If you don’t have the ability to alter this file on your web server, you’ll have to manually append the session ID to the URL of session pages if cookies are disabled with code like this:

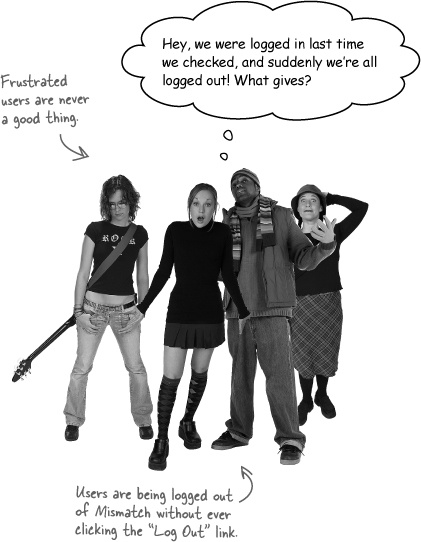

Despite serving as a nice little improvement over cookies, something about the new session-powered Mismatch application isn’t quite right. Several users have reported getting logged out of the application despite never clicking the “Log Out” link. The application doesn’t exactly feel personal anymore... this is a big problem.

The problem with the automatic log-outs in Mismatch has to do with the limited lifespan of sessions. If you recall, sessions only last as long as the current browser instance, meaning that all session variables are killed when the user closes the browser application. In other words, closing the browser results in a user being logged out whether they like it or not. This is not only inconvenient, but it’s also a bit confusing because we already have a log-out feature. Users assume they aren’t logged out unless they’ve clicked the Log Out link.

Even though you can destroy a session when you’re finished with it, you can’t prolong it beyond a browser instance. So sessions are more of a short-term storage solution than cookies, since cookies have an expiration date that can be set hours, days, months, or even years into the future. Does that mean sessions are inferior to cookies? No, not at all. But it does mean that sessions present a problem if you’re trying to remember information beyond a single browser instance... such as log-in data!

Session variables are destroyed when the user ends a session by closing the browser.

Unlike session variables, the lifespan of a cookie isn’t tied to a browser instance, so cookies can live on and on, at least until their expiration date arrives. Problem is, users have the ability to destroy all of the cookies stored on their machine with a simple browser setting, so don’t get too infatuated with the permanence of cookies—they’re still ultimately only intended to store temporary data.

Cookies are destroyed when they expire, giving them a longer lifespan than session variables.

Yes, it’s not wrong to take advantage of the unique assets of both sessions and cookies to make Mismatch log-ins more flexible.

Note

As long as you’re not dealing with highly sensitive data, in which case, the weak security of cookies would argue for using sessions by themselves.

In fact, it can be downright handy. Sessions are better suited for short-term persistence since they share wider support and aren’t limited by the browser, while cookies allow you to remember log-in data for a longer period of time. Sure, not everyone will be able to benefit from the cookie improvement, but enough people will that it matters. Any time you can improve the user experience of a significant portion of your user base without detracting from others, it’s a win.

For the ultimate in log-in persistence, you have to get more creative and combine all of what you’ve learned in this chapter to take advantage of the benefits of both sessions and cookies. In doing so, you can restructure the Mismatch application so that it excels at both short-term and long-term user log-in persistence.