Leadership in lamellar, the marshall and Mont St Michael (with added emphasis)

Our next frieze is of debating wyverns in Ringerike/Urnes, or Nordic, style, and quite different from the ones that concluded Harold’s tale(s). The style has significance. To claim a Scandinavian connection is too strong but they are indicators. They are above a column of soldiers setting out. It is a spring offensive, winter is over. One in the middle appears to wear a turban, but it may actually be a harness-cap and if so is another unique inclusion, another piece of primary evidence. Nowhere else do we have any evidence of a padded cap to wear beneath a helmet at this date. What is happening now? Once again the campaigning season has come around, though the apparently debating and non-standard wyverns shown might hint that the impending attack was not entirely justifiable. Or was it a deceit? Just possibly the whole thing has been contrived. Would the embroiderers know such things? Maybe, if someone boasted of them. William of Poitiers later claimed that Conan of Brittany had corrected his vassal Riwallon and Riwallon then appealed to Duke William for help against his lord. Not really grounds for action but possibly convenient for William. So this might make sense of these marginal hints. Anyway, fighting seems to have been close to many hearts and one did not need much of a reason to go campaigning. Warfare was a popular hobby of the rich and powerful. For Norman nobles this was just another form of hunting and what more natural than to invite their honoured guest and known soldier to participate?

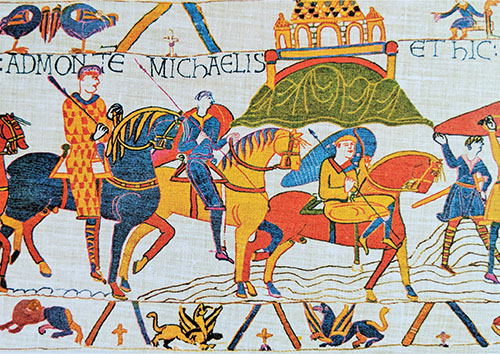

Strangely contorted, conjoined dark birds are above the dominant figure, the figure always presumed to be Duke William. Is it him? These again appear to be not real birds but shape-changers, parandri, unless they are attempts at Pliny’s description of the ostrich, which imagines itself concealed if it thrusts its head into a bush?1 No one in England had ever seen an ostrich so this description was all they had. If, however, it is our cygnus-cum-ferende gæst, or swan, then it might be either black or white and furthermore known in fables to sing a sweet song. If this is the case I wonder who is doing the siren-singing? Maybe William is hiding a secret purpose as well? Maybe he dissimulates? Maybe the siren-song is sung by someone else and for Harold? As we pass Mont St Michael, gryphons rejoice, fierce, strong, vengeful guardians of the souls of the dead. For them and for the Normans, this is a Christian parallel of Valhalla.

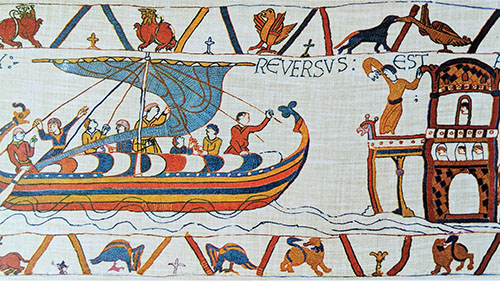

The Mont itself is no more than an arcaded and turreted charpoy on a molehill Ararat, so I doubt the designer had ever seen it for he certainly makes a better job of all the individual castles shown than he does of this notable building, whatever some historians say.2 Therefore, I doubt whether the small, seated man-in-themargin who points towards the Mont is actually telling us he was a cleric from there,3 the designer of the Tapestry. He is not, for otherwise he would have known the place much better and given it greater prominence and realism. Rather, I think he points back to emphasise a figure in the mounted column, a figure distinguished by his lamellar armour and his cudgel (in fact his marshal’s baton), supposedly William, yet it is the same picture we have of Bishop Odo of Bayeux later in the Tapestry, at the Battle of Hastings. He also rides the same black horse. Are we being told that the real hero and general of this campaign is Odo? We shall see such pointing at him for emphasis repeated later, and the seated figure could he then be Duke William, directing events through his sibling. If Odo played such a part I have no doubt he would want it recorded. And what about this strange armour of Bishop Odo’s, a suit from Outremer, more suitable for a Varangian. Is it no more than a coincidence that the wyverns noted above have Nordic styling when we have this as a possible Nordic – Varangian connection? Was one of the embroiderers Nordic? Remember the squamatid armour? Next to that was a clump of trees also in Ringerike/Urnes style. Maybe the Nordic embroiderer also worked this section? Go back and look. Anyway, wherever we have a certain identification of Duke William he is wearing western European mail armour and not something outlandish. This figure is not the duke, we can be sure of that. It cannot be anyone but the wealthy Bishop Odo and he wishes to be noticed, to be emphasised. And we shall see this confirmed several times.

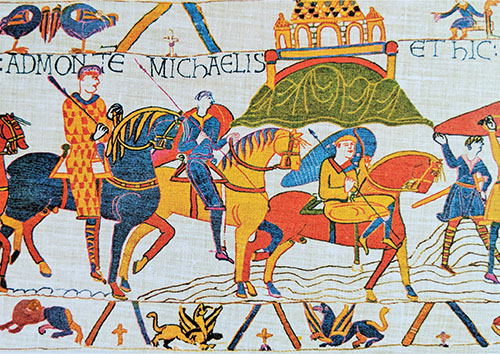

The column fords an estuary with tides and sandbanks, the dangerous estuary of the River Cousenon. Horsemen raise their feet to their saddles, foot soldiers hold their shields aloft to minimise the drag of the waters, men and horses tumble into quicksands or tidal races while fish and eels swim, ravens or carrion crows and kites look down and scream delight and (hero) Harold rescues men from a watery grave. Two fish are seen connected by what appears to be a cord, exactly the same symbol as is shown for March in the Duc de Berry’s Book of Hours.4 If this is the sign for Pisces, then we have further confirmation of spring, say late February to March, just the time of the spring tides and tidal bore of this river. In the water one man grasps an eel by the tail while in his other hand he seems to hold a knife. A pard pulls him ashore and (fierce) hawk and camel, the beast of burdens, assist him while a centaur, a creature living between two worlds but given to licentiousness, pulls the camel’s tail. Are we being told of some foolhardy attempt at fishing but also, in these several bestial attributes, given a parallel character composition of the expedition? Or is this a comment on Harold? Breughel’s Flemish proverb ‘to catch an eel by the tail’ signified a useless endeavour, so perhaps the proverb is as old as this. Maybe his display of bravery will all come to nothing. The knife would be for skinning – more than one way of skinning anything also comes to mind. If so, not everyone was impressed. Maybe only the fierce, aggressive, burdened and licentious soldiery were, that is the pards, hawks, camels and centaurs. They are the ones obviously impressed but the parandri have already warned viewers of the plurality of Harold’s character, so his actions could also be calculated to impress, or it could just be a comment on these (possibly contrived) events. It also begs the question as to how much help Harold received. Did he manage it all on his own or did he lead a rescue attempt? Let us move on.

Leadership in lamellar, the marshall and Mont St Michael (with added emphasis)

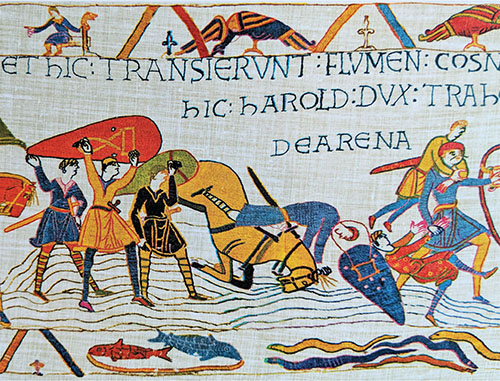

Looking down on them all we next see boars and badgers, fierce and dirty creatures with dangerous bites, then thought to be fatal. Were these opportunist brigands menacing the column’s stragglers? The castle at Dol, where Conan hides, is assaulted by dragons (firedrakes), but below it are two rejoicing hawks or eagles who congratulate one another (William and Odo or Harold and Odo) and a wyvern lies dead. Sovereignty and courage have prevailed over bile and the diabolical, and the castle appears to be on fire, so Conan makes his escape by sliding down a rope. Is it my imagination or is this a rather poor quality castle? Just how genuine is this expedition?

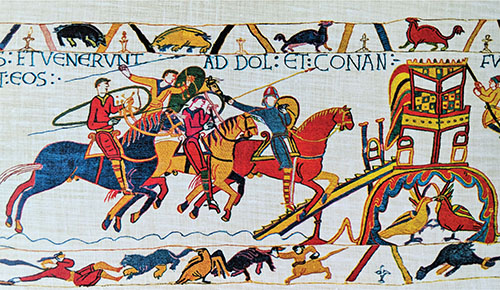

Winged lions of destiny pursue the fleeing Conan, crow and kite look down. The expedition comes to Rennes, but we can see that this has been guarded by faithful mastiffs and by geese (warning, tenacity, keeping faith), the best watchmen of all. Conan has been foiled. He carries on, having no choice, to Dinan. The pursuit has lions and winged lions confronting one another, lions are noble and brave but winged lions suggest St Mark, virtue, strength, destiny as well as bravery. Vultures look-down on Castle Dinan, where Conan finds refuge. Now the hawks bow down to William’s forces and after a fierce resistance and threat of fire Conan hands over the keys and dishonoured lions bite their tails while winged lions and an eagle rejoice. Is the eagle significant? As we shall see later, it might represent Bishop Odo himself. That would give it special significance.

Twin fish and a heroic turn

Catching eels by the tail, fire-drakes, wyvern and an escape from Dol

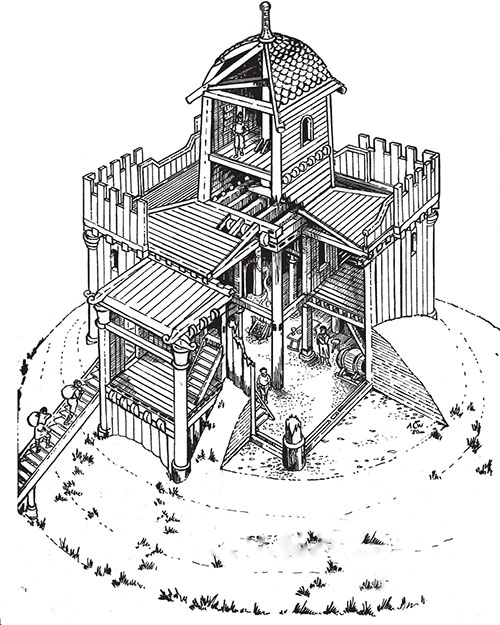

Here we should pause to remember that the Tapestry is undoubtedly the product of an English workshop. This is an important, if overlooked, consideration. Remember, there were no cameras, no records and how could the most assiduous of observers possibly remember every detail of each and every structure? Yet these castles we see are all architecturally feasible and individual. What does this tell us? The embroiderers were not given an all-expenses-paid trip to France to observe and record the castles and other buildings depicted. Neither were they given security passes into secret, military installations and, as we have seen, they were not able to say what Mont St Michael looked like, which confirms they had not visited Normandy. Nevertheless, all the castles shown are both individual and plausible structures and this can only mean one thing: that the embroiderers saw castles for themselves. These castles were, therefore, undoubtedly English and not Norman in location. We are too close to the Conquest for anything else to be possible. This really is primary evidence for it flies in the face of all the fantasies built up around Norman castles and Norman genius. Although we have no certain written or archaeological evidence of any Conquest-period Norman motte-and-bailey castles, these embroiderers (in England) had seen several castles and they had seen them before c.1070, at very latest 1080.5 Were such castles in reality always English and not Norman? That would also help to explain why we cannot prove any motte-and-bailey castles in Normandy before 1066. Let us consider this possibility before we move on.

Historians constantly dismiss all the Tapestry’s castles and buildings as conventional or schematic, 6 which completely fails to explain why they are all shown as individuals. Why not just use a castle symbol? The only possible pre-Conquest motte in France – though the motte itself is not certain – at Chateau d’Olivet Grimbosq, is mentioned by Rowley as evidence for motte-and-bailey. He accepts the suggested date of pre-1047 for the whole castle complex. I cannot find any proof of this. Some writers’ views have been extreme. ‘None of these places in reality ever looked remotely like their depiction on the Tapestry,’ said one.7 Such negative and clairvoyant rhetoric is inimical to scholastic application and scientific analyses. One might as well dismiss the whole story of the Tapestry as a fiction in order to be consistent in one’s interpretation. Why then do we not have one symbol for each building type? It is, in fact, the structures and artefacts that are most likely to be faithfully portrayed, consider that. While the storyline shown will not only be subject to individual understanding, memory and presentation, but also to political propaganda, there is no reason for structures to be falsified. It therefore stands to reason to accept these highly detailed and individual structures as just as accurate as the artefacts and clothing shown, validating them by marrying together surviving structural elements, archaeological evidence and the research of eminent architectural historians, such as the late Cecil Hewett,8 who devoted his life to early timber structures. We can only write them off as inventions if we write off everything else, pictures, stories, the lot, as pure fiction and fantasy. Where then would be the point of the Tapestry?

Years ago I determined to explore the engineering possibilities of these Tapestry castles, especially the splendid example shown at Bayeux, to see whether they could be validated as timber constructions by surviving structures and how they compared with the secular buildings shown on the Tapestry. Bringing together pre-and early post-Conquest structures, stave-churches, aisled barns and timber belfries, all with common antecedents among aisled halls, walling elements and spire-masts, I was able to construct an entirely plausible, detailed structural model of the Tapestry’s Bayeux Castle, which not only accommodated surviving archaeological evidence from the eleventh and twelfth centuries but also explains anomalous features in the succeeding phase of stone-built donjons, such as the internal galleries and the fore-buildings they feature, which otherwise appear to serve no real purpose and to have no pedigree.9 From this practical realisation, building from the foundations upwards in stages, I was able to conclude that the Tapestry’s castles did not represent cosmetic towers within ringworks, as often claimed, but instead integrated tower and box-work structures entirely conformable to the description of the fabulous tower built by Arnold, Lord of Ardres c. 1117.10 This reconstruction I believe to be the first accurate synthesis of all the available archaeological and pictorial evidence from the period. Moreover, the secular structures on the Tapestry often mirror exactly the same technical details of timber engineering that we see in the castles. From this mass of evidence, I concluded that the structures shown on the Tapestry, including the castles, were accurate observations of buildings seen in England c.1070. There is one very special caveat proving that these were English castles: the castle at Bayeux never had a motte. Neither the embroiderers nor the writer of the brief ever saw one at Bayeux. No Norman ever saw one either.

Finally, after reviewing the archaeological evidence for motte-and-bailey castles in England, Wales, Scotland and in Europe, I came to the conclusion that the concept of a motte – Old French for turf – as an artificial hillock on which to place a castle-tower probably evolved in Britain, not in France, in spite of the linguistic debt, and it evolved from fortuitous or serendipitous exploitation of natural, topographic features, probably in the immediate pre-Conquest period. Then, post-Conquest, it particularly evolved from the raising of protective and stabilising berms of turf around the outer box-works of such timber castles.

Bayeux (yet not Bayeux)

A reconstruction of a motte castle

Subsequently these castles evolved in two directions: the sinking of a tower into the up-cast earth-and-turf motte feature, or the raising of a berm (alias motte) around a wooden tower, or even a later stone donjon. Whether timber or stone buildings, berms helped to resist attempts at mining. As stave walling, an integral part of such box-works and illustrated on the Tapestry, appears to have been exported from England to Europe and Scandinavia,11 in churches and hall-structures, long before 1066, I conclude that the use of mottes might also have been exported.

The Continental use of the noun castellum is by no means synonymous with motte-and bailey – anything can be called a castle. The addition of a bailey to a motte was simply the combination of a burgh (ringwork) with a turf hillock (motte) of natural or of constructed form. Many Conquest-period Norman castles actually exhibit nothing more than just a burgh or bailey (as the post-Conquest language insisted) all of them being initially devoid of a motte of any kind.12 In both England and France there seems to have been too much enthusiasm among historians to christen all mounds ‘Norman’ and ‘mottes’. Some are undoubtedly earlier mounds (even prehistoric), some are recent garden features, and many are rather later mottes, especially in England those raised during the Anarchy. While some were castles and some were re-used as such, others were and are nothing but tumuli. It is strange that this was never noticed and investigated before.

Possible structure of motte castle with box-work and berm

Next on the Tapestry, Duke William confers arms on Harold, not in fact to confirm his warrior-ship, for he has already been a soldier in battle and trained from birth to warfare, that is why he had been invited on campaign, but as a special gift and, more sinister, a symbol of overlordship. Harold’s skill and bravery have been reported and the duke has found a suitable reward, a feudal gift and we can be sure it was the best available armour. However magnificent it was, in reality it was a trick. By accepting the gift, Harold became that man’s man, yet how could he refuse such an honour without giving offence to his generous host of the winter? Lions bite their tails and alarmed birds witness the ceremony, confirming that it is a clever device on William’s part. As they next approach the Castle of Bayeux (guarded by dark geese, or are these cygnets, cygnus, warning of shape-changing?), wyverns rejoice, though not for Harold’s contribution this time but for William’s. But not all is ominous for so do pards and winged lions. They all know that William has scored. They tell us that his retainers are rejoicing, and destiny is fulfilled. Harold is surrounded by deceit, but also by supreme power. Could there be a better description of an honoured prisoner? A pair of eagles or hawks sit on one perch, as though in a mews, grasping a sceptre-like object. Could they be Harold and William or are they William and Odo as successful plotters and raptors? Anyway, someone is professing shared regality. They might even represent another happy couple, but for clarity’s sake I will come to that later. I suspect they might represent regal promises by William to Harold, promises of shared power and continued close friendship, but only if Harold acts in William’s interest. Who would trust such promises in this eleventh-century world? Alfred (Emma’s son) had been betrayed in just this way and perhaps murdered by Harold’s father. It seems a cynical even cruel and malicious assurance on William’s part. ‘Trust me, I will be your friend.’ Once again there is ambiguity. We may choose the explanation we wish or anticipate a conclusion later in this unfolding tale of power, duplicity and ambition. ‘Here William came to Bayeux where Harold gave his oath to Duke William’ comes next on the superscript. It does not say what he swore.

As Harold swears on the holy reliquaries the winged lions of strength and destiny (here shown above William) knowingly suck their wings to stop their mouths, the eagles cover their heads with a wing, doves hide under branches, even the cunning foxes are surprised. What has he sworn? Although this is not a grand ceremony with ritual, pomp, and the presiding bishop would be Odo, it does appear to be a significant pact sealed between friends or fellow conspirators.13 Wace believed that William also tricked Harold by concealing the relics under an altar cloth until the oath had been sworn. We have to admit that some of the details in his account ring true. Of course, the embroiderers would not have been told this, so the reliquaries shown here are in full view. Are the two Englishmen next shown behind Harold the hostages? It appears that Wulfnoth was never released. Harold has had no choice in any part of these matters. He is certainly under duress. The fox has been outsmarted. Whatever oath he swore, he swore it as ‘that man’s man’, as hearth-troop member to Duke William, yet an oath extracted under duress has never been binding in law. This, however, is different. Even under English law this holy oath could be a binding obligation. If William should make a play to become king, Harold cannot plead that he was only obeying the orders of his lord or the advice of his counsellors in opposing him, for now he is bound to William. The bones of the saints add weight to the promise – a stitch-up for sure.

Swiftly the English party take ship for England as lions bite their tails and hawks or eagles cover their heads in shame. When they make land, we see a repeat of the fable of the wolf and the crane – seek no reward, you are lucky to be allowed to live – just to add emphasis. Landfall is at some castle-like building by the sea where a lookout stands on a fore-building and there are faces at the windows, keeping watch. Could this be Dover? It has never been noticed before because the English are not supposed to have had castles. But this certainly looks like a castle, one with a large garrison at the windows and possibly part masonry, the ‘gateway to England’.

So ends the first part of the Tapestry’s story with Harold’s return to England, ostensibly successful. But the margins tell us it is really in shame, a schemer outwitted, a compromised claimant. William now has the moral high ground that Harold had hoped to win for himself and, we might say, has the non-aggression pact that Harold had hoped for in his favour.

The return – to Dover? Is it pharos or castrum?