Chapter 14

Colditz Castle is a Renaissance castle in the town of Colditz near Leipzig, Dresden and Chemnitz in the state of Saxony in Germany. The castle was used as a workhouse for the poor. It was also home for the mentally sick for over 100 years. It became the most famous Prisoner of War prison during the Second World War housing the “incorrigible” Allied officers who had repeatedly escaped from other camps.

The castle lies between the towns of Hartha and Grimma on a spur over the Zwickauer Mulde and had the first wildlife park in Germany.

In 1046, Henry III of the Holy Roman Empire gave the burghers of Colditz permission to build the first documented settlement at the site. In 1083, Henry IV urged Margrave Wiprecht of Groitzsch to develop the castle site, which Colditz accepted. In 1158, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa made Thimo I “Lord of Colditz”, and major building works began. By 1200, the town around the market was established. Forests, empty meadows, and farmland were settled next to the pre-existing Slavic villages Zschetzsch, Zschadraß, Zollwitz, Terpitzsch and Koltzschen.

Around that time the larger villages Hohnbach, Thierbaum, Ebersbach and Tautenhain also emerged.

In the Middle Ages, the castle played an important role as a lookout post for the German Emperors and was the centre of the Reich territories of the Pleißenland (anti-Meißen Pleiße-lands). In 1404, the nearly 250-year rule of the dynasty of the Lords of Colditz ended when Thimo VIII sold Colditz Castle for 15,000 silver marks to the Wettin ruler of the period in Saxony.

Various renovations were completed through the Middle Ages, it was also rebuilt in 1504 when a fire which began in the bakery razed the castle to the ground.

In the 19th century, the church space was rebuilt in the neo-classic architectural style, but its condition was allowed to deteriorate. The castle was used by Frederick Augustus III, Elector of Saxony as a workhouse to feed the poor, the ill, and persons under arrest. It served this purpose from 1803 to 1829, when its workhouse function was taken over by an institution in Zwickau. In 1829, the castle became a mental hospital for the “incurably insane” from Waldheim. In 1864, a new hospital building was erected in the Gothic Revival style, on the ground where the stables and working quarters had been previously located. It remained a mental institution until 1924.

The castle was home to several notable figures during its time as a mental institution, including Ludwig Schumann, the second youngest son of the famous composer Robert Schumann and Ernst Baumgarten, one of the original inventors of the airship.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, they turned the castle into a political prison for communists, homosexuals, Jews and other “undesirables”. Beginning in 1939 allied prisoners was housed there.

After the outbreak of World War II the castle was converted into a high security prisoner-of-war camp for officers who had become security or escape risks or who were regarded as particularly dangerous. Since the castle is situated on a rocky outcrop above the River Mulde, the Germans believed it to be an ideal site for a high security prison.

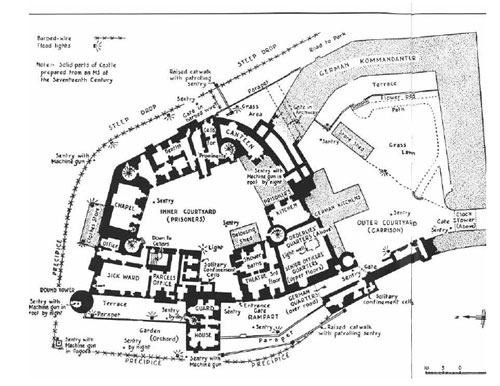

The larger outer courtyard, known as the Kommandantur, had only two exits and housed a large German garrison. The prisoners lived in an adjacent courtyard in a ninety-foot (twenty seven meter) tall building. Outside, the flat terraces which surrounded the prisoners’ accommodation were constantly watched by armed sentries and surrounded by barbed wire. Although known as Colditz Castle to the locals, its official German designation was Oflag IV-C and it was under Wehrmacht control.

Although it was considered a high security prison, it boasted one of the highest records of successful escape attempts. This could be owing to the general nature of the prisoners that were sent there; most of them had attempted escape previously from other prisons and were transferred to Colditz because the Germans had thought the castle escape-proof.

In April 1945, US troops entered Colditz town and, after a two-day fight, captured the castle on 16 April. In May 1945, the Soviet occupation of Colditz began. Following the Yalta Conference it became a part of East Germany. The Soviets turned Colditz Castle into a prison camp for local burglars and non-communists. Later, the castle was a home for the aged and nursing home, as well as a hospital and psychiatric clinic. For many years after the war, forgotten hiding places and tunnels were found by repairmen, including a radio room set up by the British POWs, which was then “lost” again only to be re-discovered some ten years later.

Reach for the Sky

Douglas Bader was born in London, England on February 21, 1910. His father, Frederick Bader, was a civil engineer and his mother Jessie, played Mah-jong.

The first two years of young Doug’s life was spent with relatives on the Isle of Man as his parents were living in India due to Fred’s work commitments. Douglas joined his parents in India from the age of two until returning home to Britain a year later.

The family settled in London. In 1914 with the outbreak of World War I, Bader’s father joined the military. Frederick was badly wounded in the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917 he was repatriated home but died as a result of his wounds in 1922.

Jessie did not grieve long and re-married soon after. She and her new husband did not want a little twelve year old getting in the way, he was sent to Saint Edward’s School as a border.

His class had an excursion to the RAF College at Cranwell; Bader set his sights on becoming a pilot and won a place as a cadet at RAF College Cranwell.

Bader was commissioned as an Officer in the Royal Air Force in 1930 and was posted to 23 Squadron at RAF Kenley. Bader demonstrated great ability as a pilot in fact he was selected to fly in the Squadron’s aerobatic display team at the prestigious RAF Hendon display in 1931.

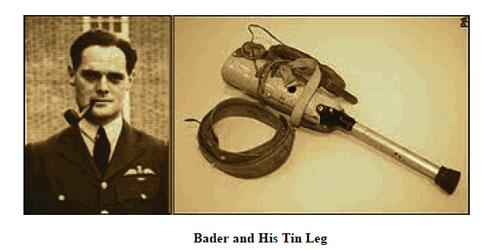

His reputation for taking risks was well known particularly in low level aerobatics. In December 1931, Bader crashed during an unauthorized low-level aerobatic routine at Woodley while visiting the Reading Aero Club. He survived the crash although he came close to death. He had both his legs amputated.

Doctors fitted him with artificial “tin” legs soon, Bader learned to walk without the use of a stick and was not only driving his car but also flying.

Douglas was certified by the Central Flying School as perfectly able to fly however, the Air Force had no precedent to guide them, they could only offer him a ground based commission. Bader resigned and found work with the Asiatic Petroleum Company.

Douglas didn’t enjoy civilian life although he was happily married and was the only golfer with tin legs playing from a ten handicap at his club.

With the outbreak of the Second World War Bader applied to rejoin the RAF. With pilots in short supply they accepted his application by June 1940 Bader had been posted to command 242 Squadron, which had suffered badly in The Battle of France.

He knew he had to raise morale; Bader’s methods were typically uncompromising. His management skills brought the 242 back into an effective fighting unit.

Bader made an impact on The Battle of Britain with his aggressive tactics and the determination of his squadron.

Bader was promoted to Wing Commander in 1941 and was sationed at RAF Tangmere, he lead the “Tangmere Wing” in sweeps over North West Europe aimed to bring the Luftwaffe into combat.

By the summer of 1941 Bader had claimed twenty two victories making him the fifth highest scoring pilot in the RAF.

Bader was flying over France in August 1941 when German fighters shot him down. Bader bailed out from his damaged machine and parachuted to the ground but both his artificial legs were badly damaged.

Bader was captured by German forces and was taken to a hospital near St Omer where his damaged artificial legs were repaired. The German hospital staff feeling sympathy for the legless pilot allowed Bader to retain his clothing. French villagers helped him break out from hospital! The locals escorted him to a farm but someone betrayed him and he was re-arrested. Taking no further chances, the Germans put Bader under close guard and he was sent to a Prisoner of War camp. Eventually he arrived at Colditz as a result of his constant and unremitting hostility to his captors.

Bader remained in captivity despite numerous escape attempts until Colditz was liberated in 1945.

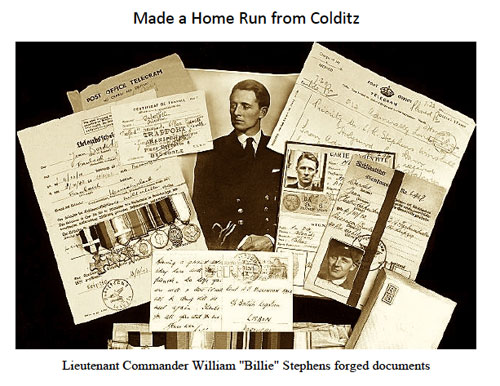

Billie Stephens

William (Billie) Stephens was the son of a Belfast shipping agent and timber importer. He was born in Belfast and educated at Shrewsbury before joining his father’s firm. He joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve in 1930 and at the outbreak of the Second World War joined the coastal forces He received a commission to command a Motor Launch, this was a relatively small vessel measuring one hundred and twelve feet, weighing eighty-five tons and was capable of speeds up to twenty knots.

Billie was heavily involved in what is now known as a famous raid on St Nazaire on the Burgundy coast on 27 March 1942. He commanded his Motor Launch 192 with considerable skill and bravery. Intelligence reports intimated that the new German battleship “Tirpitz” was now completed although in need of some last minute repairs. The size of the battleship meant the only dry dock available to her was at St Nazair on the mouth of the river Loire.

A plan was hatched, “Operation Chariot”: a daring scheme whereby the destroyer Cambeltown packed with five tons of explosives would ram the gates of the dock blowing them up. Two destroyers escorted Cambletown on her mission and an armada of smaller vessels including sixteen motor launches. As Cambletown steamed full throttle towards the gates she came under extreme enemy fire however, unstoppable, she hit the lock gates at 1.30am.

The fast and manoeuvrable motor launches drew their fare share of fire, as was their mission. Only four of the sixteen returned to Britain.

Billie Stephens was in command of one of the leading motor launches they were almost abeam of the harbour wall when the launch was hit by intensive gunfire.

Completely immobilised and on fire he had no option but to order his men to abandon ship. Managing to swim ashore carrying the wounded sailors they were taken prisoner by the Germans.

The Cambeltown eventually blew up destroying the main gate and killing a number of German officers.

Stephens and his crew were taken to a courtyard where they were searched and then lined up against a wall. The men knew their destiny. Fortunately, an officer arrived and took control ensuring the safety of the prisoners. The British officers and sailors were imprisoned in an underground store without food or water despite having several wounded men. The prisoners were then transported to Stalag 133 where they endured appalling conditions. Stephens was sent to Wilhelmshaven and interrogated at great length before being sent to Marlag. from where he made his first escape. En route to Oflag IV C (Colditz) Billie jumped from the train, he was captured the next day and sent on to Colditz to serve a week in solitary confinement.

Major Pat Reid, in The Colditz Story (1952) recalled his early impression of Stephens:

‘He was handsome, fair-haired, with piercing blue eyes and Nelsonian nose. He walked as if he was permanently on the deck of a ship. He was a daredevil, and his main aim appeared to be to force his way into the German area of the camp and then hack his way out with a metaphorical cutlass.’

Five weeks later, Stephens and Major Ronnie Littledale submitted their plan to the escape committee. It was accepted. They requested two other POWs to join them one was to have lock-picking skills. Hank Wardle was chosen for this task, along with Major Reid as the second member.

They began their extensive preparation over the following days using the experiences of other successful escapes. Reid insisted that each man carry a small suitcase to give them all a look of respectability, he thought travelling without one would signal they were fugitives.

Wearing balaclavas and socks over their shoes with their suitcases under their arms filled with sheets they began their escape.

On 14th October wearing balaclavas, gloves and socks over their shoes and carrying their suitcases muffled with blankets containing sheets, they began their escape Pat Reid led the way through a kitchen window. Once in position Reid was able to signal back to the others when the coast was clear they could then proceed through the window. The next stage was barred window, which gave them access to a flat roof well illuminated: a guard was only fifteen yards away.

The Battle of Britain pilot, Douglas Bader, was acting as an observer conducting the “Colditz Orchestra”. The plan involved the orchestra pausing when a guard had his back to them. This enabled each of the four men to make a dash for the shadows of a ventilator safely. The critical next hurdle of the escape was a narrow flue. Stripping naked they managed to squeeze through. Somewhat battered and bruised they dressed in a nearby shrubbery. Strolling nonchalantly past the sleeping sentry in the barracks they continued on. Knotting the sheets they dropped in three stages, fifty-four feet in total into a dry moat.

Billie started to cough when he reached the ground bring attention to himself and the others. He quickly stuffed his mouth full of grass and dirt in an act of desperation. The men then climbed the outer wall, which was only ten feet high. At 4am they shook hands split into two pairs and Stephens and Littledale set off together. They strolled to a station at Rochlitz trying not to bring attention to themselves.

Catching the train to Chemnitz en route to Nuremberg they changed at Hoff, where they sat in the station drinking beer. The escapees had been warned to keep away from Stuttgart; it was far too dangerous. Travelling on minor rail lines they eventually reached Tubingen. After two days of trekking they reached the Swiss border crossing under the cover of darkness. Their journey from Colditz had taken only five days.

Reid and Wardle had travelled a different route arriving the day before. All were interned in Switzerland.

The Swiss released the group after questioning, Stephens made his way to France continuing on over the Pyrenees and into Spain The Spanish authorities arrested him and once again Billie found himself in prison. Billie was a charmer, he bribed a guard with his wristwatch to allow him to telephone the British Embassy in Madrid. The British smuggled him out in the boot of a Cadillac to Gibraltar and from there he flew to the UK.

After the war Stephens returned to Northern Ireland to continue with the family business. He became chairman of Northern Bank and the Northern Ireland Tourist Board as well as Commissioner of Belfast Harbour and High Sheriff of County Down. He was also involved in the Missions to Seamen.

This debonair man, full of charisma, was always immaculate, fit and alert. He had a certain magic and an excitement to him. He was absolutely devoted to his Swiss wife Chou-chou who sheltered him after he crossed the Swiss border. They delighted in entertaining their many friends and in playing endless hours of bridge and the French edition of Scrabble. In the late Eighties they moved to France, to a cottage near Nice for the sake of her health. Her death in 1993 was a severe blow to him.

Prisoners made many attempts to escape Oflag IV-C (Colditz). Approximately thirty-six men succeeded in their attempts.

The German Army made Colditz a Sonderlager (high-security prison camp), the only one of its type located within Germany. Field Marshal Hermann Göring declared Colditz “escape-proof” yet despite this audacious claim, there were multiple escapes by British, Australian, Canadian, French, Polish, Dutch, and Belgian inmates. Despite some misapprehensions to the contrary, Colditz Castle was not used as a Prisoner-of-War camp in World War I.

Prisoners were inventive in devising methods to escape. They duplicated keys to various doors, made copies of maps, forged Ausweise (identity papers), and manufactured their own tools. MI9, a department of the British War Office which specialized in escape equipment, communicated with the prisoners in code and smuggled them new escape aids disguised in care packages from family or from non-existent charities, although they never tampered with Red Cross care packages for fear it would force the Germans to stop their delivery to all camps. The Germans became skilled at intercepting packages containing contraband material.

Prisoners also used items from their Red Cross parcels to buy information and tools from guards and local villagers.

If a P.O.W. was lucky enough to escape from Colditz they would then face the considerable challenge of negotiating their way to a neutral country.

Dutch naval lieutenant Hans Larive discovered “The Singen Route” into Switzerland in 1940. On his first escape attempt Larive was caught near Singen, close to the Swiss border. The interrogating Gestapo officer was so confident the war would soon be won by Germany that he told Larive the safe way across the border. Larive did not forget and many prisoners later escaped using this route.

Most of the attempted escapes failed. Pat Reid, a British officer, failed to escape at first but then was appointed as “Escape Officer” in charge of coordinating the various escape groups. The Escape Officer would ensure escapes were controlled and not tripping over each other’s attempts. Escape Officers were generally not permitted to escape while they held that position.

Many POWs tried unsuccessfully to escape in disguise: Airey Neave, a British officer, twice dressed as a guard and attempted to simply walk out A French Lieutenant, Boulé disguised himself as a woman. British Lieutenant Michael Sinclair even dressed as the German Sergeant Major Rothenberger when he tried to organize a mass escape, and French Lieutenant Perodeau disguised as regular camp electrician Willi Pöhnert (“Little Willi”):

On the night of 28 December 1942, one of the French officers blew out the fuse on the lights in the courtyard. As they had anticipated Pöhnert was summoned, and while he was still fixing the lights, Lieutenant Perodeau, dressed almost identically to Pöhnert and carrying a tool box, walked casually out of the courtyard gate. He passed the first guard without incident, but the guard at the main gate asked for his token — tokens were issued to each guard and staff member upon entry of the camp guardhouse specifically to avoid this type of escape — with no hope of bluffing his way out of this, Perodeau surrendered.

Dutch sculptors made two clay heads to stand in for escaping officers in the roll call. Later, “ghosts”, officers who had faked a successful escape and hid in the castle, took the place of escaping prisoners in the roll call in order to delay discovery as long as possible.

Camp guards collected so much escape equipment that they established a “Commandant’s Escape Museum”. Local photographer Johannes Lange took photographs of the would-be escapers in their disguises or re-enacting their attempts for the camera. Along with the Lange photographs, one of the two sculpted clay heads was displayed proudly in the museum.

There was only one confirmed fatality during the escape attempts: British Lieutenant Michael Sinclair in September 1944. Sinclair attempted a repeat of the 1941 French over the wire escape. Security officer Eggers warned him after which Sinclair was fired upon by guards. A bullet hit Sinclair on the elbow and ricocheted through his heart.

The Germans buried him in Colditz cemetery with full military honours — his casket was draped with a Union Jack flag made by the German guards, and he received a seven-gun salute. Post-war he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order, the only man to receive it for escaping during World War II. He is currently buried in grave number 10.1.14 at Berlin War Cemetery in the Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf district of Berlin.

Flight Lieutenant Dominic Bruce was a tiny-framed individual. He arrived at Colditz in 1942 after attempting to escape from Spangenberg Castle disguised as a Red Cross doctor. A new Commandant arrived at Colditz in the summer of 1942; he enforced rules restricting prisoners’ personal belongings. On 8 September POWs were told to pack up all excess belongings and an assortment of boxes were delivered to carry them into store. Dominic Bruce immediately seized his chance and was packed inside a Red Cross packing case, three-foot square, with just a file and a forty foot length rope made of bed sheets. Bruce was taken to a storeroom on the third floor of the German Kommandantur and made his escape that night. When the German guards discovered the bed rope dangling from the window the following morning they raced to the storeroom and found the empty box. Bruce had inscribed ‘Die Luft in Colditz gefällt mir nicht mehr. Auf Wiedersehen’! — “The air in Colditz no longer agrees with me. See you later!”

Bruce was recaptured a week later trying to stow aboard a Swedish ship in Danzig.

In late 1940, British officer Peter Allan found out that the Germans were moving several mattresses from the castle to another camp and decided that would be his way out. He let the French officers moving the mattresses know that one would be a little bit heavier. Allan, a fluent German speaker, dressed himself up in a Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) uniform, stuffed Reichsmark in his pockets, and had himself sewn into one of the mattresses. He managed to get himself loaded into the truck, and unloaded into an empty house within the town. Cutting himself out of the mattress several hours later when there was complete silence he climbed out of the window and into the garden and swaggered down the road towards his freedom.

Making his way to Vienna one hundred and sixty kilometres down the road via Stuttgart he got a lift with a senior SS officer. Allan recalled that ride as the scariest moment of his life. He had been aiming to reach Poland but soon after reaching Vienna found his money had run out. America had not yet entered the war so Allan decided to ask the American consulate for assistance; he was refused. His stepmother, Lois Allan, was a U.S. citizen he was sure the embassy would take him in. Allan had been on the run at this point for nine days; broke, exhausted, and hungry, he fell asleep in a park. Upon waking he discovered he was too weak to walk. Soon after he was picked up and returned to Colditz, where he spent the next three months in solitary confinement.

On 12 May 1941, Polish Lieutenants Miki Surmanowicz and Mietek Chmiel attempted to rappel down a thirty-six meter wall to freedom on a rope constructed out of bed sheets. In order to get into a suitable position both men orchestrated punishment in solitary confinement. After forcing open the door and picking the locks they made their way to the courtyard where they climbed up to a narrow ledge. From the ledge they were able to cross to the guard house roof, and climb through an open window on the outer wall. Utilising their bed sheet rope, they lowered themselves towards the ground. Both were caught when the German guards heard the hobnailed boots of one of the escapees scraping down the outside of the guardhouse wall. The guard who spotted the escapees shouted ‘Hände hoch!!’ [Hands up!!] to the men as they were descending the rope. As if.

The French lady

On June 5 1941, while returning from the park to the castle, some British prisoners noticed that a passing lady dropped her watch. One of the British POWs called out to her, but the lady just kept walking. This aroused the suspicion of the German guards and, upon inspection, “she” was revealed to be a French officer – Lieutenant Chasseurs Alpins Bouley.

The Canteen Tunnel

Early in 1941, the British prisoners had gained access to the sewers and drains which ran beneath the floors of the castle. Entrance to these was from a manhole cover in the floor of the canteen. After initial reconnaissance trips it was decided that the drain should be extended and an exit made in a small grassy area, which was overlooked from the canteen window. From there they planned to climb down the hill and drop below the steep outside eastern wall of the castle. The escapees knew which sentry would be on duty during the night of the escape, they pooled their resources and collected 500 Reichsmark for a bribe. This plan took three months to prepare. On the evening of 29 May 1941, Pat Reid hid in the canteen after it had been locked up for the night. Having removed the bolt from the lock on the door, he returned to the courtyard. After evening roll call the escapers slipped into the canteen unnoticed.

They entered the tunnel and waited for the signal to proceed. Unknown to the prisoners, they had been betrayed by the bribed guard. Waiting on the grassy area to greet them was Hauptmann Priem, the commandant and his guard force.

Pat Reid recalls:

“I climbed out on to the grass and Rupert Barry was following close behind. My shadow was cast on the wall of the Kommandantur, and at that moment I noticed a second shadow beside my own. It held a gun. I yelled to Rupert to get back as a voice behind me shouted, Hände hoch! Hände hoch!. I turned to face a German officer levelling his pistol at me.”

Behind him were seven British and four Polish officers. On his order the remaining men backed up the tunnel to evade detection but the Germans were waiting for them outside the canteen. Not wanting to give their captors any satisfaction the British burst into laughter as they came out.

Hauptmann Priem ends the story:

“And the Guard? He kept his 100 Marks; he got extra leave, promotion and the War Service Cross.”

The French Tunnel

Nine French officers organised a long-term tunnel-digging project, the longest attempted out of Colditz Castle throughout the war. Deciding that the exit should be on the steep drop leading down towards the recreation area, outside the eastern walls of the castle. The officers began to scout for a possible location for the entrance.

Lieutenants Cazaumayo and Paille had previously gained access to the clock tower in 1940. Both officers knew how to solve the problem. Their tunnel began at the top of the chapel’s clock tower and descended nearly nine meters into the ground using the shaft containing the ropes and weights for the clock.

They discovered the weights and chains had been removed. This left an empty shaft, which extended from the clock to the cellars below. After the 1940 escape attempt by Cazaumayo and Paille the doors, which provided access to the tower, had been bricked up in order to prevent further attempts. However, by sealing up the tower the Germans had in essence provided a secure location. Now work could be done without being noticed. The French gained access to the tower from the attic and descended thirty-five meters to the cellars. Work began on a horizontal shaft in June 1941. This shaft work would continue for a further eight months.

The horizontal shaft towards the chapel progressed four meters before they hit rock the decision was taken to dig upwards towards the chapel floor. From here the tunnel continued underneath the wooden floor of the chapel for a distance of thirteen and a half meters. For this to be achieved, seven heavy oak timbers in the floor had to be cut through. Homemade saws assembled from table knives were employed for this task.

Once completed, the tunnel dropped vertically from the far corner of the chapel a further five meters. The tunnel then proceeded out towards the proposed exit with two further descents separated by shafts in the stone foundations of the castle. The tunnel now ran a horizontal distance of forty-four meters reaching a final depth of eight and a half meters below the surface.

Tunnelling continued well into 1942. By then Germans knew that the French were digging somewhere, based on the noise of their digging reverberating through the castle at night. The French thought the tunnel’s entrance was undetectable. However, on 15 January the Germans eventually searched the clock tower. Noise was heard below, and after lowering a small boy down the shaft three French officers were found. After searching the cellar thoroughly the entrance to the tunnel was eventually discovered a mere two meters short of completion. The French officers were convinced they had been betrayed by one of their own countrymen but this was never proven.

The tunnel had electric lighting along its whole length, powered by electricity from the chapel. Five large stones covering a small door, which left little trace of any hole, concealed the entrance to the tunnel in the wine cellar

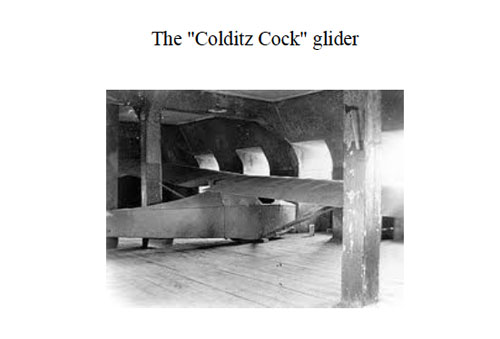

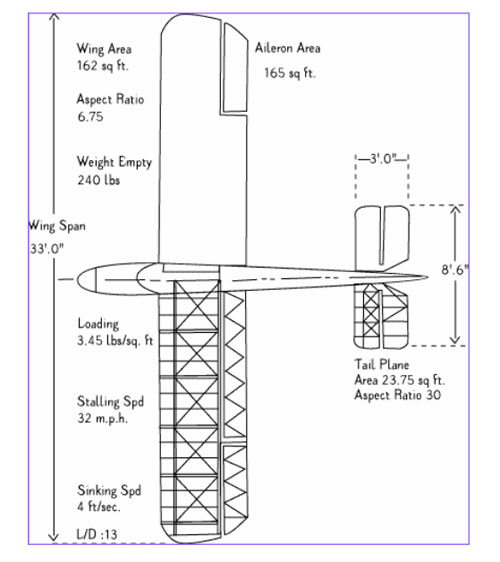

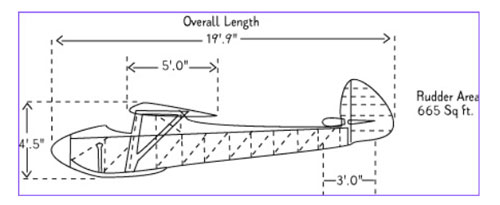

One of the most ambitious and imaginative escape attempts from Colditz was the idea of building a glider and flying to freedom. The idea came from two British pilots, Jack Best and Bill Goldfinch. Two army officers, Tony Rolt and David Walker who had recently arrived in the camp, encouraged them. It would be Tony Rolt who would recommend the chapel roof; he noticed it was obscured from the view of the Germans.

The two-man glider was to be assembled by the two pilots in the lower attic above the chapel it was to be launched from the roof to give it the elevation to fly across the river Mulde which was about sixty meters below. The runway was constructed from tables and the glider was to be launched using a pulley system based on a falling metal bathtub full of concrete, which would accelerate the glider to fifty kilometres an hour.

Prisoners built a false wall to hide the space in the attic where they slowly built the glider out of stolen wood. The Germans were incensed on discovering tunnels not secret workshops therefore the prisoners felt safe from detection. However, they still placed lookouts and created an electric alarm system to warn the builders of approaching guards.

Hundreds of ribs for the fuselage had to be constructed; they smuggled in timber predominantly from bed slats but also from every other piece of wood the POW’s could obtain. The wing spars were constructed from floorboards. Control wires were made from electrical wiring taken from unused portions of the castle. A glider expert, Lorne Welch, reviewed the stress diagrams and calculations made by Goldfinch.

The resulting glider was to be a one hundred and nine kilograms two-seater, high wing, monoplane design. It had a Mooney style rudder and square elevators. The wingspan was thirty three feet and the fuselage length was nineteen feet. Prison sleeping bags of blue and white checked cotton were used to provide the skin for the glider. German ration millet was boiled and used to seal the cloth pores.

The war ended before the glider was finished.

It was flown for a film on Colditz and it was a successful flight.

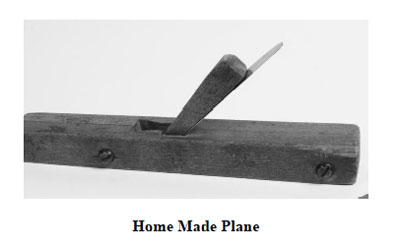

Tools Created for the Construction

Side-framed saw

handle of beech bed board

frame of iron window bars

blade of gramophone spring with 8 teeth / in (3 mm teeth)

Minute saw for fine work

gramophone spring blade, 25 teeth / in (1 mm teeth) 5/8 in (16 mm)

metal drill obtained by bribery

Drill bits for making holes made from nails

A gauge made of beech, with cupboard bolt and gramophone needle

Large plane, 14½ in (368 mm) long

2 inch blade obtained by bribing a German guard

Wooden box (four pieces of beech screwed together)

Small plane, 8½ in (216 mm)

long blade made from a table knife

Plane, 5 in (127 mm) long

Square made of beech with gramophone spring blade

Set of keys including:

Universal door pick, forged from a bucket handle

Successful Escape attempts

It is claimed that there were thirty-six “home runs” i.e. successful escapes from Colditz.

At the end of May 1943, the Armed Forces High Command decided that Colditz should hold only British and Commonwealth officers As a result all of the Dutch and Polish prisoners and most of the French and Belgians were moved to other camps in July. Three British officers tried their luck by impersonating French officers when they were moved out but they were later returned to Colditz. German security gradually improved and by the end of 1943 most of the potential avenues of escape had been eliminated. Several officers tried to escape during transit without success.

Some officers faked illnesses including mental illness in order to be repatriated on medical grounds. A member of the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), Captain Ion Ferguson wrote a letter to an Irish friend suggesting Ireland join the war; the censors stopped the letter but his wish to be moved elsewhere was granted.. Four other British officers claimed symptoms of stomach ulcer, insanity, high blood pressure and back injury in order to be repatriated. However, there were also officers who went genuinely insane.

French Lieutenant Alain Le Ray escaped April 11, 1941. He hid in a terrace house in a park during a game of football. He was the first successful Colditz escaper and the first to reach neutral Switzerland.

French Lieutenant René Collin escaped May 31, 1941. He climbed into the rafters of a pavilion during exercise hiding there until dark he slipped away. He made it back to France.

French Lieutenant Pierre Mairesse Lebrun escaped July 2, 1941. He was captured. At a later date he vaulted over a wire fence in a park with the help of an associate. He reached Switzerland in eight days on a stolen bicycle.

Dutch Lieutenant Hans Larive escaped August 15, 1941. He hid under a manhole cover in the exercise enclosure emerging after nightfall Hans took a train to Gottmadingen reaching Switzerland in three days.

British Lieutenant Airey M. S. Neave escaped January 5, 1942. He crawled through a hole in a camp theatre to a guardhouse and marched out dressed as a German soldier, reaching Switzerland two days later.

Dutch Lieutenant Anthony Luteyn escaped January 5, 1942 with Neave.

British Lieutenant Hedley Fowler escaped September 9, 1942. Slipped out with four others through a guard office and a storeroom dressed as German officers and Polish orderlies. Only he and Van Doorninck reached Switzerland. Like Luteyn and Neave, this was another successful British Dutch effort.

Dutch Lieutenant Damiaen Joan van Doorninck escaped September 9, 1942 with Fowler.

British Capt. Patrick R. Reid escaped October 14, 1942. He slipped through the kitchen into the German yard then into the Kommandantur cellar and down to a dry moat through the park. He took four days to reach Switzerland.

Canadian Flight Lieutenant Howard D. Wardle (RAF) escaped October 14, 1942 with Reid.

British Major Ronald B. Littledale escaped October 14, 1942 with Reid.

British Lieutenant-Commander William E. Stephens escaped October 14, 1942 with Littledale.

British Lieutenant William A. Millar escaped January, 1944. He broke into a German courtyard and hid in a truck intending to go to Czechoslovakia. He never reached home and is listed missing on the Bayeux memorial. There is speculation that he was caught and executed in Mauthausen concentration camp as a victim of the secret Kugel-erlass (Bullet Decree) July 15, 1944.

French Lieutenants J. Durand-Hornus, G. de Frondeville and J. Prot escaped while on a visit to the town dentist December 17, 1941.

Polish Lieutenant Kroner was transferred to Königswartha Hospital where he jumped out of the window.

French Lieutenant Boucheron fled from Zeitz Hospital, was recaptured, and later escaped from Düsseldorf prison.

French Lieutenants Odry and Navelet escaped from Elsterhorst Hospital.

British Captain Louis Rémy escaped from Gnaschwitz military hospital. His three companions were captured, but he reached Algeciras by boat, and later Britain.

British Squadron Leader Brian Paddon escaped to Sweden via Danzig French Lieutenant Raymond Bouillez escaped from a hospital after an unsuccessful attempt to jump from a train.

Dutch Lieutenant J. van Lynden slipped away when the Dutch were moved to Stanislau camp.

French Lieutenant A. Darthenay escaped from a hospital at Hohenstein-Ernstthal, later joined the French Resistance, and was killed by the Gestapo on April 7, 1944.

Indian RAMC Captain Birendra Nath Mazumdar M.D. was the only Indian in Colditz. He went on a hunger strike to have himself transferred into an Indian-only camp. His wish was granted three weeks later and he escaped from that camp to France and reached Switzerland in 1944 with the aid of the French Resistance.

W. E. “Wally” Hammond (from the sunken submarine HMS Shark) and Don “Tubby” Lister (from the captured submarine HMS Seal) campaigned for a transfer from Colditz, arguing that he was not an officer. He was transferred to Lamsdorf prison escaped from a Breslau work party and reached England via Switzerland in 1943.

Colditz was not the prison Goring described as ‘escape proof’ the officers from the allied countries showed initiative, courage and invention to prove him wrong.