Chapter 19

America, the home of the brave, baseball and hotdogs had been at war for three years and in that time had established over five hundred POW camps across the land.

Four hundred thousand German POWs were transported to the United States during World War II. Like their Allied counterparts in German POW camps they believed it was their duty to escape. There were over two thousand individual attempts by the Germans to flee their camps. Prisoners scaled fences, smuggled themselves out in or under trucks or jeeps, passed through the gate in makeshift GI uniforms. They cut the barbed wire or tunnelled under it they even went out with work details and simply walked away. Their motives ranged from trying to find their way back to Germany (which none ever did) to merely enjoying a few hours, days, or weeks of freedom.

One particular camp, Papago Park in Arizona, housed more than three thousand German naval officers and sailors. To date it had been a very difficult camp to manage with attempted escapes and a lack of discipline being a major problem.

Towards the end of 1944 things seemed to change especially in compound 1A where the U-Boat commanders and crews were kept. They had been the worst offenders now their compound was neat and tidy and the prisoners seemed more content and in good spirits. The guards were amazed and delighted with the change of attitude. Could these troublemakers be the same men who were now tending flowerbeds and playing sports including volleyball on the court they had constructed themselves?

The prisoners were so proud of the volleyball court they groomed the surface several times a day. The guards put this fastidious behaviour down to German efficiency.

Captain Parshall an experienced camp official pointed out that there was a spot in Compound 1 that could not be seen from the guard towers.

‘Those Germans were a fine bunch of men, smart as hell,” he said later.

‘It made no sense to put the smartest of them in Compound 1. I knew they would discover that blind spot.’

There was in fact a blind spot in Compound One that could not be seen from the guard towers. This would be a great spot to begin a tunnel.

The Geneva Convention exempted officers and NCOs from work detail, allowing them to sleep late and spend their days plotting ways to get beyond the wire.

Lieutenant Wolfgang Clarus, who had been captured in North Africa recalled.

‘You stare at that fence for hours on end, try to think of everything and anything that can be done, and finally realize there are only three possibilities: go through it, fly over it, or dig under it.’

The officers in Compound 1A decided that an escape should be attempted and the logical method would be to dig a tunnel. A committee was established to manage the dig and tunnelling began in September 1944.

In September 1944 the digging began under the management of four officers, all U-boat captains, including Fritz Guggenberger, who had been personally decorated by Hitler for the exploits of his U Boat.

‘The tunnel became a kind of all-consuming sport. We lived, ate, slept, talked, whispered, dreamed ‘tunnel’ and thought of little else for weeks on end.’ Recounted Guggenberger.

Utilizing the blind spot the men chose the entrance shaft location three and a half feet from the bathhouse, which was the closest building to the perimeter fence.

A board was loosened on the side of the bathhouse creating a passageway and a coal box was moved to conceal the entrance to the tunnel.

The modus operand was the officers and men would enter the bathhouse to shower or wash their dirty clothes. Once inside they would slip down into the tunnel’s six-foot deep vertical entrance shaft and begin their shift.

Three groups of three men worked ninety-minute shifts during the night, one man digging with a coal shovel and small pick, the second lifting soil in a bucket to the third man topside, who also served as the lookout.

As is always the case with digging illicit tunnels the major problem is getting rid of the dirt without drawing attention to yourself or the dirt itself. At Papago they created a dedicated group to distribute the dirt the day after the dig.

They flushed it down toilets, stored it in attics, or let it slip through holes in their pockets onto the new flowerbeds. As the tunnel progressed, a small cart was fashioned out of a shower stall base to haul the dirt back to the entrance.

Soil piled up at such an alarming rate that a new means for getting rid of it had to be found. A captain in the group suggested they request a volleyball court be constructed, as a healthy way to keep the men occupied in the compound. The Americans thought that was a splendid idea and gave the go ahead. The ground they were to use was very rocky and uneven so it had to be levelled. The prisoners became very enthusiastic spreading the soil from the tunnels using rakes and shovels supplied by their captors.

A Colonel visiting the camp to inspect security declared ‘this camp need never worry about prisoners digging out: the soil is as hard as a rock. He was standing right atop the concealed tunnel entrance at that moment

By their calculations the tunnel needed to be one hundred and seventy eight feet long enabling the tunnel to reach an electric light pole in a clump of bushes. This would route the tunnel under two fences and a patrol road.

Food provisions were going to be critical their main staple was to be breadcrumbs mixed with milk and water. Not very appetising but would fill their stomachs and it would be easy to carry.

The forgers were able to produce passports and identity papers from various odd and sods found around the camp including photos taken by the Americans and sent back to Germany to prove how well they treated German POWs.

On December 20 the tunnel had reached the desired length; to ensure they would exit at the electricity pole Guggenberger pushed a fire poker through earth. Prisoners in the compound could see that it was close to the pole, elation spread through the compound.

The escapees were ready to depart on the evening of 23 December. It had been arranged that their neighbours in Compound 1B would create plenty of noise. They certainly did, they drank homemade schnapps sang German songs and had a good old time.

Under cover of this diversion, the escape began through the bathhouse. The escapers proceeded in ten teams of two or three men each, some carrying packs laden with spare clothing, breadcrumbs and other food. Other teams carried medical supplies, maps and cigarettes. Shortly before nine o’clock in the evening, the first team, Quaet-Faslem and Guggenberger descended the entrance ladder and began struggling through the tunnel on elbows, stomach, and knees, pushing their packs ahead of them.

The journey took a little more than forty minutes. Guggenberger climbed the exit ladder and cautiously lifted the cover. A light rain was falling as he and his companion emerged into a clump of bushes and dashed down into the waist-deep ice-cold water of the nearby Crosscut Canal. By 2:30 a.m. all twenty-five prisoners; twelve officers and thirteen enlisted men had exited the tunnel and were making their way through a hard rain outside the wire of Papago Park. Colleagues who stayed behind closed up both ends of the tunnel.

The agreed plan was only to travel under cover of darkness avoiding trains or buses. Some hoped to cross into Mexico where they knew German sympathisers and hoped they would be assisted in getting back to Germany. They all knew in their heart of hearts their chance of returning to Germany was very slim.

In the meantime they revelled in being free on Christmas Eve.

Some found stables where they rested amongst the bales of hay and ate their Christmas Eve meal of breadcrumbs. Others found abandoned shacks where they could eat and play “Silent Night” on the harmonica and others kept going right through the night.

On Sunday afternoon, Christmas Day, the Americans were due to conduct the head count. The German officers remaining demanded an officer, not a Sergent, conduct the rollcall. This delayed things somewhat. Therefore, it wasn’t until 7pm before the camp administration became aware of a mass break out.

It was about 7.30pm when Parshall was certain that a large group of prisoners were missing. He telephoned the FBI to report names and descriptions of the escapees.

While he was still on that call, another telephone rang. It was the sheriff in Phoenix reporting they had an escaped POW in custody. Herbert Fuchs, a twenty-two-year-old U-boat crewman, had quickly grown tired of being wet, cold, and hungry and hitch hiked a ride to the sheriff’s office. Soon after a Tempe woman called to say that two escapees had knocked on her door and surrendered; the telephone rang again, a man reported that two hungry and cold POWs had turned themselves in.

The Sheriff took one more call on Christmas Eve from Tempe railroad station informing him that another escapee had been arrested. This was Helmut Gugger a Swiss national who had been drafted into the German navy. Gugger revealed to the Americans the existence of the still-hidden tunnel the following day.

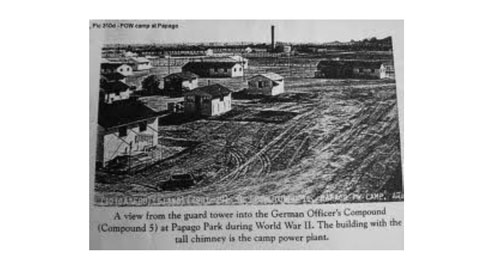

With a number of escapees already in custody authorities launched what the Phoenix Gazette headlined as “the greatest manhunt in Arizona history.” Soldiers, FBI agents, sheriff’s deputies, police, border patrol, and customs agents all joined the search for the nineteen German escapees still at large. Ranchers and Indian scouts attracted by the $25 reward carried mug shots of the escapees.

‘We didn’t think we were that important.’ Guggenberger remarked later.

J. Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI, repeatedly warned the American public about the dangers posed by escaped German prisoners. In reality, there was not a single recorded instance of sabotage or assault on an American citizen by an escaped POW.

Any crimes committed were typically the theft of an automobile or of clothing needed for the getaway.

After Christmas, most of the remaining nineteen prisoners moved south travelling under cover of darkness. Capture was a possibility at any moment; they were also cognisant of the fact that no fewer than fifty-six escaped German POWs were shot to death while escaping

Over the next fourteen days the German escapees either handed themselves in or were captured.

Their great escape was over except for the punishment, which turned out to be surprisingly light. Despite the egregious lapses in security, no American officer or guard was court-martialled. Some of the escapees half-expected to be shot however, they were merely put on bread and water for every day they were absent from camp.

Clarus said of the tunnel: “Conceiving of it, digging it, getting out, getting back, telling about our adventures, finding out what happened to the others…why, it covered a year or more and was our great recreation. It kept our spirits up even as Germany was being crushed and we worried about our parents and our families.”