Chapter 1

William Leefe Robinson was the youngest of seven children, born in Southern India on the 14th July 1895. His father, Horace Robinson, had a coffee plantation and the family was quite wealthy.

Young William or Billy as he was called had a privileged childhood and as the youngest child tended to be spoiled not only by his parents but his older sisters.

Life was one big playground and for the cheeky Billy, education was a very firm last on his list of priorities.

He attended “Dragon School” at Oxford for a year before returning to India to complete his education in Bangalore at the “Bishop Cotton School”. Billy then went on to secondary education at “St Bees College” Cumbria. Unlike his elder brother who excelled in school Billy barley passed his grades.

It was sport where William excelled; he won his house cap for football, was a key member of the hockey team and was a keen rower.

Billy enjoyed the London social scene with trips to the theatre and many parties to attend. The dashing young man was also very popular with the young ladies. A promotion to Sergeant in the school’s Officer Training Corp was seen as a very positive move by his parents.

Things were about to change for William and the entire family as 1914 approached, two of his sisters married and he was appointed head of Eaglesfield House. He also enjoyed his time with the OTC and experienced life in the army at various camps.

In March 1915 he joined the Royal Flying Corps, and was posted to No 4 Squadron at St Omer. His role was to fly a BE2cs on reconnaissance patrols over German lines. It was during one of these flights he received shrapnel wounds and was on sick leave for a month.

Reporting back for duty at Farnborough on 29th June 1915 he began flying immediately.

On 2nd February 1916, Robinson was transferred to Sutton’s Farm at Hornchurch. Part of 19th Reserve Squadron under Major T. C. Higgins. This airfield was nothing more than a paddock which they shared with sheep which often invaded the runway.

The hangers were merely tents housing two aircraft. The squadron soon grew to eighteen aircraft and wooden hangers replaced the tents.

On the afternoon of the 2nd September 1916, sixteen airships, twelve from the German Naval Airship Division and four from the Army Division, set out for England on what was to be the biggest air raid of the war. The Zeppelins were carrying thirty-two tons of bombs. The Germans were going to teach the English a lesson they would never forget.

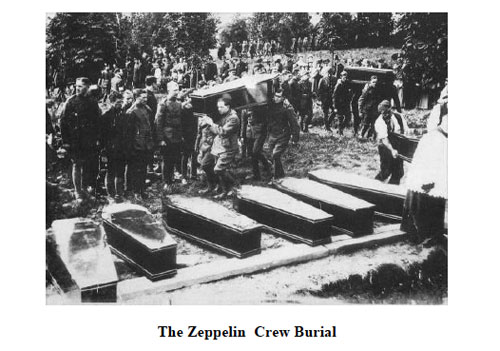

In command of the lead airship was Hauptmann Wilhelm Schramm, an experienced captain who knew the London area well. He was born at Old Charlton, Kent, and lived in England until the age of fifteen. Each Zeppelin had a crew of sixteen comprising of machinists, gunners, an ‘elevator’ man and ‘bomb’ man, officers and Captain.

At approximately 11pm the Home Defence squadrons were put on alert. Radio messages from the airships had been intercepted, and a welcoming party was prepared. Ten aircraft were sent up that night. First away was William Robinson, the fog was thick but Robinson was convinced it would be clear at a higher altitude. He had three drums of ammunition and just enough fuel to keep him aloft for three and a half hours.

The Zeppelins approached London from the north passing over Royston and Hitchin dropping their bombs over what they believed to be the London docks. Lehmann, an experienced captain, took his ship up to 13,000 feet. One of the crew spotted an aircraft approaching the airship. Robinson had seen the Zeppelin illuminated by searchlights and had climbed up to meet it. Lehmann, with a much lighter ship now that half his bombs were gone, promptly headed for cloud and continued to climb. He disappeared. Robinson was concerned he had already been in the air for two hours and had only one and a half hours flying time left.

Half an hour later, Lehmann was wreaking destruction over North London. The Finsbury and Victoria Park searchlights found him over Alexandra Palace the gunners filled the sky with anti aircraft fire. The zeppelin captain turned his craft and headed for Walthamstow trying to dodge the searchlights. Hundreds of Londoners watched, but no matter how close they burst, the ground defence’s shells seemed to have no effect.

Robinson had given up searching for the airship he had lost in the clouds, attracted by the activity over Ponder’s End he headed for what he presumed must be another airship. William spotted the airship being blasted by shellfire and headed straight for the Zeppelin. The watching crowd below swelled as the news spread that a pilot was within striking distance of the hated ‘Zepp’. Then, the firing stopped, the searchlights swung frantically searching for the enemy, the airship found cloud cover and disappeared from sight.

As suddenly as it had vanished, the airship reappeared. Every gun roared and the night sky came alive again. Robinson’s aircraft was rocked by the blasts, but closed in.

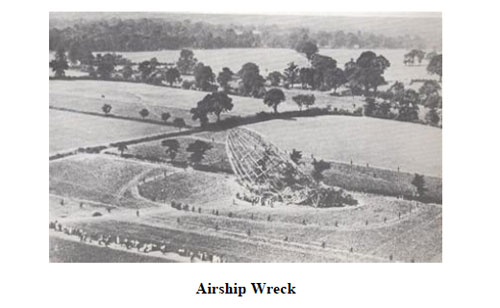

His first drum of ammunition was ready; he flew alongside the airship firing his guns riddling the fuselage with bullets. Turning his aeroplane around he viewed the Zeppelin. The airship appeared to be completely unharmed by the attack. Robinson raked the length of the vessel a second time. Still, there was no real damage. It seemed the massive craft was impregnable. William had one drum of ammunition left and very little fuel. The plane was now behind and slightly below the airship, he decided to change tactics. He dived at the thin end of the craft, heading for the twin rudders above and below the elevators. He fired into that one area. Now the guns of the ground defences were silent and all eyes were fixed on the airship. They had no idea what the pilot was doing. Within seconds the tail section was alight, and flames over one hundred feet burst out into the darkness. It did not take long for the entire Zeppelin to be in flames. The hydrogen that kept it airborne ignited turning night into day. The spectators were enthralled.

The blazing wreckage of the Zeppelin slowly fell to earth.

William Robinson turned his plane for home feeling an incredible sense of achievement.

With his fuel tanks almost empty he landed at Sutton’s Farm at 2.45am three and a half hours after take off, he was exhausted. The excited ground crews milled around the aircraft, with a cheer they lifted the hero shoulder high in triumph from his aircraft to the office.

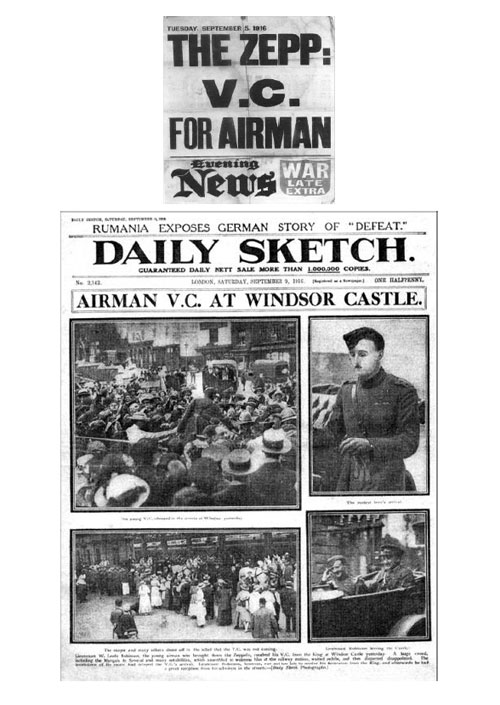

“I recommend Lieut W. L. Robinson for the Victoria Cross for the most conspicuous gallantry displayed in this successful attack.” - Lieutenant General Henderson

The V.C. was awarded.

On the 5th September 1916, the London Gazette announced the award;

“War Office 5th September 1916. His Majesty the King has been graciously pleased to award the Victoria Cross to the undermentioned officer, Lieutenant William Leefe Robinson, Worcestershire Regiment and Royal Flying Corps. For most conspicuous bravery. He attacked an enemy airship under circumstances of great difficulty and danger, and sent it crashing to the ground as a flaming wreck. He had been in the air for more than two hours and had previously attacked another airship during his flight.”

The British public had discovered the perfect ‘gentleman’ hero.