Chapter 3

For Robinson the next twenty months proved to be difficult. He was as famous in Germany as he was in England, but in Germany he wasn’t adored he was loathed.

The German prison authorities and the guards who were charged with his detention mistreated badly.

The reason for this treatment was not only because he had been awarded a V.C. and revered as a hero, it was because he was a habitual “escaper”.

Soon after arriving in Freiburg Robinson and his good friend Second Lieutenant Baerlin of 16 Squadron attempted to dig a tunnel under the perimeter fence but were apprehended by guards.

The second attempt was made with the aid of a guard who they attempted to bribe; despite the guard accepting the offer the attempt failed. The authorities heard of the plot and Robinson and Baerlin were arrested; a date was set for a formal court martial.

With incredible bravado, Robinson promptly attempted to escape again A gate to a courtyard had remained unlocked deliberately; he and his cohorts opened it and hung their washing on the line. This was meant to conceal the movements of the escapers.

A locked door stood between the prisoners and freedom. The plan included an orderly who had been a locksmith prior to the war. He role was to pick the lock.

However, he refused at the last minute in case he was caught by the guards and punished severely for aiding an escape.

The third plan had failed; the inner door was shut once again, and the Germans knew nothing of the attempt.

A fourth plan was formed within twenty-four hours of the third plan being abandoned.

A tunnel was dug under their barracks a staircase was uncovered which led to an adjoining church. The group of officers forming the escape party gathered in the church. Prising open a window the first man climbed through and dropped into the street below. The streets of Freiburg had become familiar to the prisoners during their daytime excursions. They quickly made their way out of town and split up. Robinson, Baerlin and another officer made their way towards the Swiss frontier. Travelling at night, they eventually arrived at the border. Four miles outside Stohlingen, and four miles from freedom, all three were arrested.

After four attempts in as many months, Robinson’s reputation as a trouble maker had well and truly been established. In October the court martial commenced, he was sentenced to a months’ solitary confinement. Baerlin was sentenced to three months. They were sent to the underground fortress of Zorndorf; a daunting place.

There had never been an escape from Zorndorf. Underground tunnels led to the dark cells. The only exit was up a long sloping tunnel which emerged in the centre of a mound ringed by wire and searchlights. Robinson said very little about his time as a prisoner at Zorndorf when he returned to England. Without doubt this must have been the worst of his experiences. To a man who suffered from claustrophobia solitary confinement underground must have been a living nightmare.

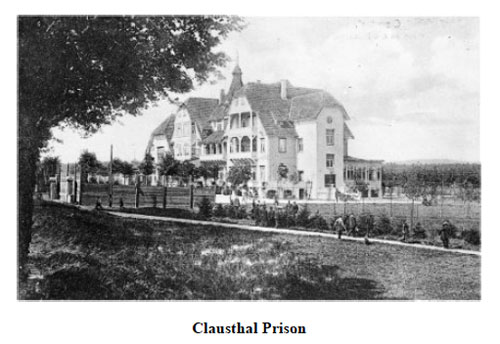

On the 2nd May 1918 Robinson was transferred to a third camp Clausthal, in the Hartz Mountains. Along with two other officers he was boarded onto a train. Immediately an escape plan was hatched. One officer was to distract one of the guards while the other two made a jump for it. The plan was fraught with danger and unfortunately for Robinson, he didn’t make it.

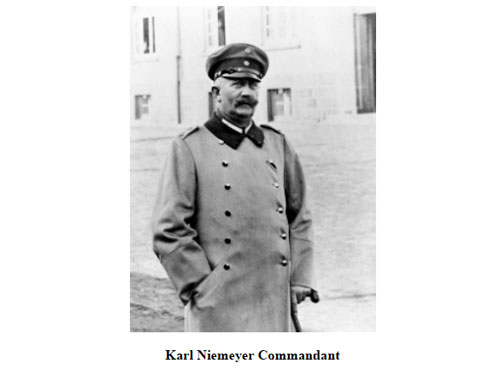

Arriving at Clausthal, Robinson was met by one the infamous Niemeyer twins, Heinrich. Heinrich and Karl Niemeyer were Commandants of Clausthal and Holzminden camps respectively. Their harsh treatment of prisoners was legendary.

They had spent some time in America before the war and had learnt a little rudimentary English including many swear words. Their fits of rage directed at the prisoners uttering stupid threats in very strange English would have been hilarious if it had been in other circumstances. In the POW camps where the Commandants had wide ranging powers, the brothers were feared and hated not just by the prisoners, but by the German guards also.

Heinrich Niemeyer, nick named by the prisoners as “Milwaukee Bill,” took an instant dislike to Robinson whose reputation had preceded him. Initially, life was tolerable.

Robinson received the privileges due to an officer P.O.W. and his pass card survives; evidence that he was allowed a certain amount of freedom. In view of his preoccupation with escaping, the wording of the card is a little ironic.

“By this card I give my word of honour that during the walks outside the camp, I will not escape nor attempt to make an escape, nor will I make any preparations to do so, nor will I attempt to commit any action during this time to the prejudice of the German Empire. I give hereby my word of honour to use this card only myself and not give it to any other prisoner of war.”

The Red Cross was active at Clausthal; their mandate was to ensure life was as comfortable as possible for all prisoners. Letters from home helped to keep morale reasonably high. Robinson’s mail included letters from well wishers who still remembered the “Hero of Cuffley.”

Robinson’s time at Clausthal came to an end in July 1918.

In his book “Cage Birds” Squadron leader H. E. Hervey M.C. who knew Robinson well and shared in many of the attempted escapes, remembers his departure:

“This month Robinson left the camp. The Commandant had taken an instant dislike to him at their first meeting, probably as a result of Robinson’s reputation. Anyway, he seized the first opportunity of getting rid of him, and handed him over to the tender care of his brother at Holzminden. Robinson was a cheerful soul and I regretted his departure, for, since our first encounter at Douai the day after I was shot down, we had moved together from camp to camp. I never saw him again.”

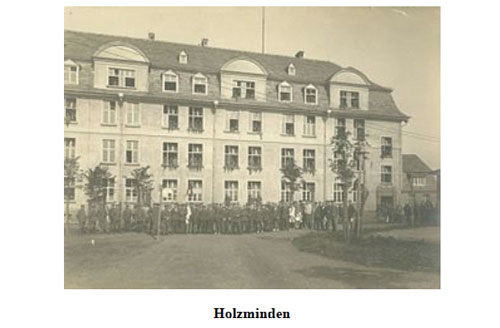

The last camp to hold William Leefe Robinson was Holzminden. Here, under Karl Niemeyer, William was treated cruelly and was continually persecuted. Robinson didn’t help things much when at the first opportunity he escaped with another officer, Captain W. S. Stephenson of 73 Squadron. Karl Niemeyer detested escapers; he saw them as deliberately undermining his position and credibility with his superior officers. They were both recaptured and Robinson was thrown into solitary confinement. Niemeyer raged and shouted at him using his crazy American-English.

H. G. Durnford of the R.A.F. was British Adjutant at Holzminden. In his book “The “Tunnellers of Holzminden” he describes the treatment meted out to officers who attempted to escape:

‘They were locked in the ground floor cells of “A” Kaserne where the “flies and staleness of the atmosphere were correspondingly oppressive … These particular rooms used to be visited two or three times a night by a Feldwebel with an electric torch, which he used to flash on the occupant of each bed in turn, thereby effectively waking everybody up.’

Robinson was about to embark on his greatest escape not alone but with more than fifty of his fellow officers . He had to conquer his greatest fear, claustrophobia, if he was to be successful in his final escape.