Industrial warfare dawned as a crusade; noble, chivalric, Homeric. The reality was to prove very different. You can tell this was written before the cold reality had become apparent.

Shall we forget them?

They who marched with smiles away,

When dawned the long-expected day,

Of German making

High were their heads and firm their lips,

As they trod the street to the waiting ships,

Then eastwards taking.

Shall we forget them?

Men of blood who gave up life

In a noble cause in day of strife,

And to glory trod.

Or, in the days to come shall our children tell

The story of those who fighting fell?

For England and for God!

J. Cooke

Haldane’s reforms earlier in the new century had swept away the old militia system in favour of the modern pattern of Territorials. Kitchener was not a fan. His own experience when serving as a volunteer with the French equivalent in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870−71 had, quite wrongly, led to mistrust. One of the first Territorial units to serve in the Great War, thrown into the cauldron of First Ypres, was the Northumberland Hussars; a former yeomanry (cavalry) regiment with indelible links to their home county and known, affectionately, as the ‘Noodles’.

The Noodles thor a’ gentlemen,

Respected to be sure,

They nivor like the rifle curs,

Fixed ramrods of the Moor; the riflemen black-legged us a’,

Undermined wor daily pay,

But smash, aw’ll fight him for a quart

Then for war lads, clear the way.

Joe Wilson

With the Noodles went Peter the cat, their somewhat grumpy mascot, who was handed over as they set off for France. The war did nothing for Peter’s humour and he rightly refused to ever alight from his privileged perch atop the ration cart. He did, however, survive the war and came safe home to medals and a gentlemanly retirement, although not with any evident good grace!

Fear death?

I would hate that death bandaged my eyes and forbore

And bade me creep past,

No! Let me taste the whole of it, fare like my peers

The heroes of old,

Bear the brunt, in a minute pay gladly life’s arrears,

Of pain and darkness and cold;

For sudden the worst turns the best to the brave,

The black minute’s at end

And the elements rage, the fiend-voices that rage

Shall dwindle, shall blend,

Small change shall become first a peace out of pain

Then a light …

Anon.

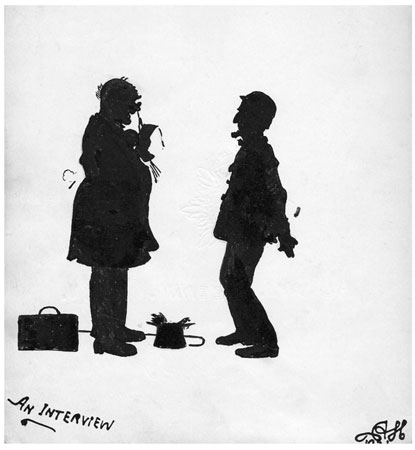

Adulation for those in khaki and white feathers for those without: like most enthusiasms, the passion for feathers was transient and the seemingly endless casualty lists published daily in the press soon sapped public ardour. Meanwhile, the Kaiser, with the real and imagined atrocities of his forces blazoned across the press and subject to ‘spin’, became a caricature.

An Interview. (Drawing in autograph book, 1914–18, author’s own)

Is there anyone I’ve forgot?

Kaiser Wilhelm said to his Chancellor one day,

I have got a new game I’m going to play,

I am de best ruler in de world today

I vill send out ultimatums!

Of course I vill be ruler of every land

Almighty Gott is my second-in-command

When I go to heaven, he vill sit on my right hand,

Or I vill send him an ultimatum!

Anon.

On Tyneside, as in other industrial centres with large Scottish and Irish contingents, volunteers formed units which reflected their own native tradition. This was not always popular with the high command, fearful of ethnic dissent.

The Fiery cross is out, now

There’s a beacon on each hill,

The Scottish pipes are sounding,

’Tis the slogan wild and shrill.

Anon.

A healthy dash of cynicism would often follow the dire realities of industrial warfare.

I heard the bugles callin’ an’ join I felt I must,

Now I wish I’d let them go on blowin’ till they bust!

Anon.

When Herbert Waugh, a young volunteer with the ‘Tyneside Commercials’ who was blooded and wounded at St Julien in 1915, finally returned from war, he would be sounding an altogether more sombre note:

Do you remember (you at the street corner or you in your private office), the thaw near Peronne which turned dry trenches into miniature canals, the march up to Arras in the snow, when someone burst a blood vessel and died by the roadside, the promulgation of a court martial before daybreak near a Belgian farmhouse, followed by a volley in the next field and, within two hours, a newly filled grave in the field beyond.

Do you remember that peculiar smell which had only one meaning; the miles of duckboard track, with horrid caricatures floating in the slime beneath? Do you remember the March retreat in 1917 when the unit strolled thirty miles across country in seven days, half asleep, defending a road here and a wood there? Do you remember when, on one parade, the battalion numbered two officers and less than 20 men, when the French shot some of us (quite by accident) and our own gunners (again by accident) shot others?

Disillusionment was for the future. In 1914 it was all about the good fight:

Three cheers for wor brave Tommies, wherever they may be,

Likewise to wor allies which lie beyond the seas;

They’ve fitten well together, nyen kin that deny

They went away determined, to conquer or to die.

Chas Anderson

Kipling’s ‘Tommy Atkins’, generally despised in peacetime, was now elevated to noble stature:

God bless wor gallant armies, on the sea and land,

Splendid deeds they have done, we hear from every hand,

In fact there’s none can beat them for stability, courage and skill,

They stand predominant above all others, I trust they always will.

Chas Anderson

Gushing, leaden sentimentality is not entirely a modern phenomenon; in 1919 we plunged knee deep into an ecstasy of righteous, patriotic zeal:

Old England’s emblem is the Rose,

There is no other flower,

Hath half the graces that adorn,

The beauty of the bower:

And England’s daughters are as fair

As any bud that blows

What son of hers who hath not loved

Some bonny English rose.

Who hath not heard on one sweet flower,

The first among the fair,

For whom the best of English hearts,

Have breathed a fervent prayer?

Oh, may it never be her lot

To lose that sweet repose

That peace of mind which blows now

The bonny English rose.

If any bold enough there be

To war against England’s Isle,

They soon shall find for English hearts,

What charms hath woman’s smile,

Thus nerved, the thunder of their guns,

Would teach aspiring foes,

How vain the power that defies

The bonny English rose!

Charles Jeffrys

Drawing of a friend – W. Moore. (Drawing in autograph book, 1914–18, author’s own)

From, stern, unsmiling Kitchener, the message was rather more restrained:

You are ordered abroad as a soldier of the King to help our French comrades against the invasion of a common enemy. You have to perform a task which will need your courage, your energy, your patience. Remember that the honour of the British army depends on your individual conduct… Be invariably courteous, considerate and kind. Never do anything likely to injure or destroy property and always look upon looting as a disgraceful act.

Do your duty bravely,

Fear God,

Honour the King.

Nobody expected the war that was to follow. This was industrial war, powered by technology and waged on a scale never seen before. When Hiram Maxim asked an American friend in the 1880s how best to employ his creative talents, it was suggested he should invent new machines for mass killing so European armies could slaughter each other even more effectively. He obliged and produced the machine gun.

The air is filled with loud hurrahs

For the bold and dashing King’s Hussars,

Who on the 24th May

To fame and glory carved their way

Positions held, ‘spite deadly fire

Thousands saved from a funeral pyre

‘Beyond all praise’ the words were true

They did as the 15th always do.

Here’s a motto for all – a motto for you,

Behave as the 15th always do!

A.B. Crump

Reality was to prove very different and far less glamorous. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) first encountered the Germans at Mons on 23 August 1914, and then again at Le Cateau three days later. After the deliverance of the Marne and the beginnings of position warfare, one last chance for the combatants to potentially outflank each other arose at Ypres. It was a name largely unknown, but one which would resonate.

I want to tell you now sir

Before it’s all forgot

That we were up at Wipers [Ypres]

And found it very hot

Plum & Apple (magazine of the Northumberland Hussars), September 1915

The First Battle of Ypres raged through the autumn of 1914. The line held, but only just, and at a fearful cost. The ‘Old Contemptibles’ of the BEF were terribly thinned when the cold, wet and mud of Flanders closed about the survivors. From now on it was to be position warfare, with every yard of ground bitterly contested and paid for in blood.

I don’t want to join the army; I don’t want to go to war,

I’d rather hang around Piccadilly underground,

Living on the earnings of a high born lady

Anon.

![]()

My son, beware the aircraft that flies above for his nose-caps return to earth as thou walkest, and if one drop near thee, though thou say ‘pooh’ yet shall thy feet be cold under thee.

Tread carefully the end of the duckboard in the trench, lest haply the other end rise and smite thee. Speak fair unto the ASC that when thou returnest from leave, he may give thee lifts in his Lorries.

Better Maconochie [stew] and biscuit in rest, than chicken and Moulin Rouge in the line, at a whizz-bang shalt thou shrug thy shoulders, at two thine eyebrows raise, at three shalt thou quicken thy pace, at four peradventure thou mayest run but a ‘five-nine’ who can stick it?

If a man say unto you ‘Leave is open, leave is open’ regard him not for he is a liar, and talketh through his hat (tin). Walk not upon the Decauville Track though it is the shorter way, that the wrath of the OC descend not upon thy head and he dock thy leave.

Beware the barrage that creepeth and the Minen that is Werfer that thy days may be long in the line. Verily, a sandbag is a comfortable thing, it buildeth up the parapet, it improveth the dugout and maketh warm the legs of man.

A simple soul accepteth twenty-five francs to the pound but a wise man insisteth on twenty-seven fifty and raiseth Cain till he gets it. From the unit to the field ambulance is easy, from thence to the CCS mayhap harder but from the CCS to the base hospital, who shall wangle it?

Ernest Mathers, 16th London Regiment Queen’s

Westminster Rifles

There was action at sea in 1914; defeat and then victory in the South Atlantic with the battles of Coronel and the Falklands:

THE Isle Juan Fernandez off Valparaiso Bay,

’Twas there that Cradock sought

The action that he fought

For he said: ‘To run from numbers is not our English way,

Nor do we question why

We are fore-ordained to die.’

Though his guns were scooping water and his tops were blind with spray.

In the red light of the sunset his ships went down in flame,

He and his brave men

Were never seen again,

And Von Spec he stroked his beard, and said: ‘Those

Englishmen are game,

But their dispositions are

More glorious than war;

Those that greyhounds set on mastiffs are surely much to blame.’

Then the Board of Admiralty to Sir Doveton Sturdee said:

‘Take a proper naval force

And steer a sou’west course,

And show the world that England is still a Power to dread.’

Like scorpions and whips

Was vengeance to his ships,

And Cradock’s guiding spirit flew before their line ahead.

Through tropic seas they shore like a meteor through the sky,

And the dolphins in their chase

Grew weary of the race;

The swift grey-pinioned albatross behind them could not fly,

And they never paused to rest

Upon the ocean’s breast

Till their southern shadows lengthened and the Southern

Cross rode high.

Then Sir Doveton Sturdee said in his flagship captain’s ear:

‘By yon kelp and brembasteen

’Tis the Falkland Isles, I ween,

Those mollymauks and velvet-sleeves they signal land is near,

Give your consorts all the sign

To swing out into line,

And keep good watch ’twixt ship and ship till Graf von Spee appear.’

The Germans like grey shadows came stealing round the Horn,

Or as a wolf-pack prowls

With blood upon its jowls,

Their sides were pocked with gun-shots and their guns were battle-worn,

And their colliers down the wind

Like jackals trailed behind,

’Twas thus they met our cruisers on a bright December morn.

Like South Atlantic rollers half a mile from crest to crest,

Breaking on basalt rocks

In thunderous battle-shocks,

So our heavy British metal put their armour to the test.

And the Germans hurried north,

As our lightning issued forth,

But our battle-line closed round them like a sickle east and west.

Each ship was as a pillar of grey smoke on the sea,

Or mists upon a fen,

Till they burst forth again

From their wraiths of battle-vapour by wind and speed made free;

Three hours the action sped,

Till, plunging by the head,

The Scharnhorst drowned the pennant of Admiral von Spee.

At the end of two hours more her sister ship went down

Beneath the bubbling wave,

The Gneisenau found her grave,

And Nürnberg and Leipzig, those cities of renown,

Their cruiser god-sons, too,

Were both pierced through and through,

There was but one of all five ships our gunners did not drown.

’Twas thus that Cradock died, ’twas thus Von Spee was slain,

’Twas thus that Sturdee paid

The score those Germans made,

’Twas thus St. George’s Ensign was laundered white again,

Save the Red Cross over all

The graves of those who fall,

That England as of yore may be Mistress of the Main.

I.C. Colvin

Ian Colvin (1877–1938) was a journalist and historian. Born in Inverness, the son of a Free Church Minister, he worked in India and South Africa before becoming a leading writer on the Morning Post, an ultra-conservative newspaper, in 1911. His pen name whilst working in South Africa was ‘Rip van Winkle’.

LET me get back to the guns again, I hear them calling me,

And all I ask is my own ship, and the surge of the open sea,

In the long, dark nights, when the stars are out, and the clean salt breezes blow,

And the land’s foul ways are half forgot, like nightmare, and I know

That the world is good, and life worthwhile, and man’s real work to do,

In the final test, in Nature’s school, to see which of us rings true.

On shore, in peace, men cheat and lie but you can’t do that at sea,

For the sea is strong; if your work is weak, vain is the weakling’s plea

Of a ‘first offence’ or ‘I’m only young,’ or ‘It shall not happen again,’

For the sea finds out your weakness, and writes its lesson plain.

‘The liar, the slave, the slum-bred cur let them stay ashore, say I,

‘For, mark it well, if they come to me, I break them and they die.

‘The land is kind to a soul unsound; I find and probe the flaw,

‘For I am the tears of eternity that rock to eternal law.’

I love the touch of the clean salt spray on my hands and hair and face,

I love to feel the long ship leap, when she feels the sea’s embrace,

While down below is the straining hull, o’erhead the gulls and clouds,

And the clean wind comes ‘cross the vast sea space, and sings its song in the shrouds.

But now in my dreams, besides the sounds one always hears at sea,

I hear the mutter of distant guns, which call and call to me,

Singing: ‘Come! The day is here for which you have waited long.’

And women’s tears, and craven fears, are drowned in that monstrous song.

So whatever the future hold in store, I feel that I must go

To where, thro’ the shattering roar, I hear a voice that whispers low:

‘The craven, the weak, the man with nerves, from me they must keep away,

Or a dreadful price in shattered nerves, and broken health they pay.

But send me the man who is calm and strong, in the face of my roaring blast,

He shall tested be in my mighty fires, and if he shall live at the last,

He can go to his home, his friends, his kin, to his life e’er war began,

With a new-found soul, and a new-found strength, knowing himself a man.’

Imtarfa (Anon.)

The editor of The Muse in Arms, an anthology of British war poetry, identifies ‘Imtarfa’ as a naval officer.

An early naval epic was the career of the German surface raider Emden, brought to a final Götterdämmerung by HMAS Sidney. Henry Newbolt (1862–1938) was a barrister, playwright and author. A friend of Sir Douglas Haig, he was recruited by the War Propaganda Bureau to promote a positive view of the conflict and keep the British public on side – work that earned him a knighthood in 1915. He was fascinated by the sea and the Navy and went on to publish two volumes of the official history of the war at sea.

The captain of the Emden

He spread his wireless net,

And told the honest British tramp

Where raiders might be met:

Where raiders might be met, my lads,

And where the coast was clear,

And there he sat like a crafty cat

And sang while they drew near

‘Now you come along with me, sirs,

You come along with me!

You’ve had your run, old England’s done,

And it’s time you were home from Sea!’

The seamen of old England

They doubted his intent,

And when he hailed, ‘Abandon ship!’

They asked him what he meant:

They asked him what he meant, my lads,

The pirate and his crew,

But he said, ‘Stand by! your ship must die,

And it’s luck you don’t die too!

So you come along with me, sirs,

You come along with me:

We find our fun now yours is done,

And it’s time you were home from sea!’

He took her, tramp or trader,

He sank her like a rock,

He stole her coal and sent her down

To Davy’s deep-sea dock:

To Davy’s deep-sea dock, my lads,

The finest craft afloat,

And as she went he still would sing

From the deck of his damned old boat

‘Now you come along with me, sirs,

You come along with me:

Your good ship’s done with wind and sun,

And it’s time you were home from sea!’

The captain of the Sydney

He got the word by chance;

Says he, ‘By all the Southern Stars,

We’ll make the pirates dance:

We’ll make the pirates dance, my lads,

That this mad work have made,

For no man knows how a hornpipe goes

Until the music’s played.

So you come along with me, sirs,

You come along with me:

The game’s not won till the rubber’s done,

And it’s time to be home from sea!’

The Sydney and the Emden

They went it shovel and tongs,

The Emden had her rights to prove,

The Sydney had her wrongs:

The Sydney had her wrongs, my lads,

And a crew of South Sea blues;

Their hearts were hot, and as they shot

They sang like kangaroos

‘Now you come along with me, sirs,

You come along with me:

You’ve had your fun, you ruddy old Hun,

And it’s time you were home from sea!’

The Sydney she was straddled,

But the Emden she was strafed,

They knocked her guns and funnels out,

They fired her fore and aft:

They fired her fore and aft, my lads,

And while the beggar burned

They salved her crew to a tune they knew,

But never had rightly learned

‘Now you come along with me, sirs,

You come along with me:

We’ll find you fun till the fighting’s done

And the pirate’s off the sea

Till the pirate’s off the sea, my lads,

Till the pirate’s off the sea:

We’ll find them fun till the fighting’s done

And the pirate’s off the sea!’

Henry Newbolt

The war was not over by Christmas and the casualty lists grew longer. Despite the attrition of First Ypres, belief in the justice of the Allied cause was not yet significantly shaken. Amongst those whose fervour had not yet fled was Orlando Wright, a Northern artisan who is best remembered as a minor working-class poet. He had one published volume, A wreath of leisure hours, including an elegy on the Hartley Colliery Catastrophe in 1862. Much of his output is found in the newspapers of the period.

Hated and hiss’d by lost ones in my dream,

I wake and turn to hide me from their glare;

But midnight darkness and the morning beam

Entrench me in the horrors of despair.

What book I read has murder on its page,

And wreck and ruin proved in bloody lore;

Could clotted grief, too dense for tears, assuage

Mine should some havoc of the past restore

No green blades quiver to my fallen eye

No brooks splash music to my languid ear;

The barren landscape smokes for ever dry

With all the world upon its funeral bier.

Standing before my conscience I can feel

Its thrust divide the marrow of my should;

But worse, alas, is truth no arts conceal,

Close write and clear on Time’s relentless scroll.

Oh! Mad ambition, soar no higher yet,

For, cross winds blowing, I may lower fall;

Kings can aspire to what they never get,

Or, getting nothing, think they’re getting all.

Orlando Wright, Illustrated Chronicle, 21 August 1915

A thousand crosses mark the way

From town to town in Flanders fair,

The sons of Judas still betray,

And thorns of steel are everywhere.

The Iron Cross a shadow throws

Across a continent of woes.

A Man of Sorrows once endured

The paid that freed imprisoned Love,

That, by a Man of Iron’s lures

Lies bleeding ‘neath the bolts of Jove.

Where’er the Iron Cross ascends,

The head of love in anguish bends.

Around the sacred Cross of wood

Still shines the light of peace to be,

The conquest on that Holy Road

Is Love’s eternal victory;

This passion, too, shall pass away,

Freedom shall win its Easter day.

A.W., The Echo and Evening Chronicle (possibly A.W. Woodbridge, editor of the Sunday Chronicle until 1925)