Kos is an easy island to explore, with good public transport for independent sightseeing, as well as abundant outlets for renting cars, scooters or push-bikes. There’s no need to take an organised tour.

This guide explores Kos Town first. Next there’s a tour around the island, starting with Platáni and the nearby Asklepion, then continuing around the coastline before forays into the interior. Finally there are excursions to (or more rewardingly, overnight stays on) a half-dozen smaller nearby islands.

The ruins of the Roman Agora and the Loggia Mosque ,Kos Town

Getty Images

Kos Town

Minoan settlers were attracted by Kos’s only good natural harbour, opposite ancient Halikarnassos (modern Bodrum), and despite regular, devastating earthquakes throughout its history, Kos Town 1 [map] has remained there, prospering from seaborne trade. The contemporary city spreads in all directions from almost landlocked Mandráki port. Apart from the imposing Knights Hospitaller’s castle, the first thing visible arriving by sea, its most compelling attractions are abundant Hellenistic and Roman ruins, many only revealed by a 1933 earthquake, and some quirky Italian architecture.

Despite a population of 19,432 – well over half the islanders – Kos Town feels uncluttered, thanks to its sprawling, flat layout. Areas of open space alternate with a hotchpotch of archaeological zones, surviving Ottoman quarters, and Italian-built mock-medieval, Rationalist and Art Deco-ish buildings, designed in two phases (1926–1929 and 1934–1939) either side of the earthquake by architects Florestano di Fausto, Rodolfo Petracco and Armando Bernabiti. Plans incorporated, as always, a Foro Italico, the Italian administrative complex close to the castle, and a Casa del Fascio (Fascist Headquarters), with the inevitable speaker’s tower for haranguing party rallies gathered on the central square below. The maze-like Ottoman core aside, this is a planned town, with pines and shrubbery planted by the Italians now fully matured, especially in the garden suburb extending east of the centre, its worker and officer housing mostly the work of Mario Paolini.

Neratziá Castle

An obvious first stop is Neratziá Castle (Castle of the Knights) A [map] (June–Sept Tue–Sun 8am–6.40pm, Oct–May 8am–2.40pm; charge), reached by a causeway over its former moat. The moat was long ago filled and planted with palms (fínikes) – thus the avenue’s Greek name, Finíkon. The original Knights’ castle which stood here from 1314 until 1450 has vanished without trace, replaced by the existing inner castle (1450–78). This nestles within an outer citadel, built to formidable thickness between 1495 and 1514 to withstand advances in artillery technology following unsuccessful Ottoman sieges in 1457 and 1477. The fortification walls make an excellent vantage point for photographs over Mandráki.

Tumbled columns in Neratzia Castle

Britta Jaschinski/Apa Publications

A fair proportion of ancient Kós, as masonry fragments and tumbled columns, has been incorporated into the walls of both strongholds or, more recently, piled up loose in the southeast forecourt. Escutcheons and coats-of-arms on various walls and towers will appeal to heraldry aficionados, as the period of construction spanned the terms of several Grand Masters and local governors of the Knights. The south corner of the older castle, for example, bears two Grand Masters’ escutcheons, best admired from the massive, most technically advanced southwest bastion, identified with Grand Master Fabrizio del Caretto, who finished the job. Dozens of cannonballs lie about, few if any fired in anger, since this castle surrendered peacefully in accordance with the terms ending the marathon 1522 siege of Rhodes.

Signs of Life

The biggest explosion that ever occurred at Neratziá castle was orchestrated for the finale of Werner Herzog’s black-and-white first feature film, Signs of Life (1968), in which a low-ranking Wehrmacht soldier goes berserk in 1944 and torches an ammunition dump inside the castle.

Hippokrates’ plane tree and the Loggia Mosque

Steel scaffolding has replaced the ancient pillars that once propped up sagging branches of Hippokrates’ plane tree, immediately opposite the causeway leading into Neratziá castle. At seven hundred years of age, this venerable tree has a fair claim to being among the oldest in the Mediterranean, though it’s not really elderly enough to have seen the great healer himself. The trunk has split into four sections, which in any other species would presage imminent demise, but abundant root-suckers promise continuation. Adjacent stand a hexagonal Turkish pillar fountain, another fountain draining into an ancient sarcophagus (neither running now), and the imposing 1786-built mosque of Gazi Hasan Pasha, better known as the Loggia Mosque B [map] after its covered northern portico. The upper two stories are locked and window tracery still bears marks of wartime bombardment. The ground floor – like that of its contemporary (1780) the Defterdar Mosque on nearby Platía Eleftherías – is occupied by tourist-orientated shops. This is not sacrilegious desecration, but common Ottoman practice; the shopkeepers’ rent goes towards the upkeep of the mosque overhead.

The ancient town

The largest excavated section of ancient Kos is the agora C [map], a sunken zone (unrestricted access) reached from either Ippokrátous or Nafklírou streets. The latter, a pedestrian lane (and lately much-subdued nightlife mecca), is separated from Platía Eleftherías by the Pórta tou Fórou D [map], all that remains of the outer city walls which the Knights erected between 1391 and 1396.

What you see is confusing and jumbled owing to successive earthquakes in 142, 469 and 554 AD; the most salient items are the foundations of a massive double Aphrodite sanctuary roughly in the centre of the site, some columns of a Hellenistic stoa near the Loggia Mosque, plus two re-erected columns and the architrave of the Roman agora itself, on the far west.

Another, more comprehensible section of the ancient town, the western excavations E [map] (unrestricted access), abuts the ancient acropolis – where Platía Diagóras lies today. Intersecting marble-paved Roman streets (Cardo and Decumana), dating from the third century AD, lend definition to this area, as does the Xystós, or colonnade, of a covered running track. Inside the Xystós the hulking brick ruins of a bath squat alongside the original arch of its furnace room. South of the Xystós stands the restored door-frame of a baptistry belonging to a Christian basilica erected above the baths after 469 AD. The floor of the basilica, as well as that of an unidentified building at the northern end of the excavations, retain well-preserved mosaic fragments, although the best have been carted off to Rhodes. What remains tends to be under several inches of protective gravel or off-limits to visitors, like the famous Europa mosaic house to the north of Decumana street – though it, plus others nearby showing gladiators, a boar being speared and sundry gods or muses, can be viewed from a distance.

Secreted in a cypress grove across Grigoríou tou Pémptou Street is a fourteen-row Roman odeion F [map], which in ancient times hosted musical events associated with the Asklepieia festivals (for more information, click here); it was re-clad in new marble during 1999–2000 and again is a popular concert venue.

Statuary inside the Archaeological Museum

Britta Jaschinski/Apa Publications

Archaeological Museum

The north side of Platía Eleftherías is dominated by the newly refurbished Archaeological Museum G [map] (Tue–Sun 8.30am–2.40pm; charge), designed and built in 1935 in severe Rationalist style by Rodolfo Petracco. The Italians’ original choice of exhibits was a none-too-subtle propaganda exercise, with a distinct Latin bias. Four galleries containing good, if not superlative, statuary are grouped around a central atrium where a Roman mosaic shows Hippokrates welcoming Asklepios to Kos. The most famous exhibit, a statue thought to portray Hippokrates, is in fact Hellenistic, as is a vividly coloured, fragmentary fish mosaic at the rear of the atrium. But most of the other highly regarded works – Hermes seated with a lamb, Artemis hunting, Hygeia offering an egg to Asklepios’ serpent, a boxer with his arms bound in rope, statues of wealthy townspeople – are emphatically Roman.

The Casa Romana

The Casa Romana H [map] (Tue–Sun 10am–5.40pm; free), at the south edge of town, re-opened in 2015 after a five-year refit, well worth the wait; it now effectively functions as a museum of domestic, late-Roman (3rd–4th centuries AD) life. During World War II it served as an Italian infirmary – until 2010 you could still see faded red crosses painted on the exterior to deter Allied bombers.

The structure, devastated by the 554 AD earthquake but abandoned long before, was evidently the villa of a wealthy family, arrayed around three atria with third-century tessellated marble or mosaic floors. The mosaic closest to the ticket booth shows a lion and a leopard respectively mauling two stags; the largest courtyard to the south is flanked by rooms, on opposite sides, depicting another panther and a tiger; while the pool of the third atrium is surrounded by dolphins, fish and two leaping leopards, plus a damaged nymph riding a horse-headed sea-monster, possibly a representation of Poseidon. Standouts amongst the small finds displayed are a relief of a nekrodeipno (funerary banquet) with the goddess Kybele presiding; a figurine of Venus adjusting her sandal; and elaborate ‘Knidos-style’ oil-lamps.

The Ottoman old town: Haluvaziá

Kos’s medieval ‘old town’, the former Muslim district of Haluvaziá I [map], lines either side of a pedestrianised street running from behind the Italian-era market hall on Platía Eleftherías as far as Platía Diagóras and the orphaned minaret of the earthquake-tumbled Yeni Kapı Mosque overlooking the western excavations. It was long considered an undesirable area, but while all the rickety townhouses nearby collapsed in the 1933 earthquake, the sturdily built stone dwellings and shops here survived. Today, they are crammed with superfluous tourist boutiques, cafés and tavernas; one of the few genuinely old things here is a dry Turkish fountain with an Ottoman inscription, found where the walkway cobbles cross Venizélou. Another juts out from the wall of the barber shop at the corner of Hristodoúlou and Passanikoláki, next to the minaret-less but still-functioning Atik Mosque (refurbished in the 19th century), whose name means ‘Mosque of the Freed Slaves’.

Café life in Platía Eleftherías

Britta Jaschinski/Apa Publications

Italian Monuments

If you’re at all interested in local Italian monuments, a worthwhile first stop is the well-done display ‘The Creation of the New Town of Kos’ (daily 10am–10pm; charge), housed appropriately enough in the former Italian-built veterinary compound. Photos and documents chart Italian social policy, the 1933 earthquake’s aftermath, prominent architects, and their best buildings.

The seafront Foro Italico extending southeast from Neratziá castle, erected during 1927–29, comprises the local administration building, now the police station; the adjoining courthouse, still in use; the graceful Albergo Gelsomino J [map], abandoned and in poor repair; the mayor’s residence, today the municipal cultural centre; the Italian officers’ club, now the Avra Lounge Bar; and inland opposite Evangelismós Church K [map], originally the Catholic cathedral of Agnus Dei. From the same era, but on the far side of the harbour entrance, stands the crenellated power plant, with the town hall found en route, behind Aktí Koundouriótou.

Casa del Fascio

iStock

Post-earthquake monuments are more scattered, dating mostly from 1934–35. Notable ones include the Casa del Fascio L [map] (today part-occupied by the winter Orfeas cinema) with its prominent clock-tower/speaker’s balcony; the covered market M [map] or dimotikí agorá, a fun if expensive place to souvenir-shop; and the aforementioned archaeological museum – all flanking focal Platía Eleftherías. Further afield are the exceptionally eclectic synagogue N [map] at Alexándrou Diakoú 4; the round-fronted, seafront primary school O [map], at the base of Kanári; the Fascist Youth building P [map] at the corner of Venizélou and Koraí, now a branch of Pireos Bank; and the circular 1937 Amnós tou Theoú Q [map] (Agnus Dei) Catholic church. Many other mixed-use buildings pop up around town, with shops on the ground floor and residences upstairs. Much of the fun in strolling around is spotting them – there’s a particularly extravagant one at the corner of Venizélou and Vasiléos Pávlou.

The Linopótis Massacre

Amnós tou Theoú was originally the chapel of the surrounding Catholic cemetery, containing a memorial honouring Italian officers executed by the Germans on 6 October 1943.

After Italy capitulated on 8 September 1943, Hitler ordered the shooting of captured Italian officers who assisted the British or declined to fight again for Germany. The British seized Kos on 14 September, and with the Italian garrison resisted German attacks until being overwhelmed on 3 October. Taken prisoner were 148 Italian officers; just seven opted to fight again, while 38 escaped to Turkey. The remaining 103 were marched across a field between Linopótis and the Tingáki salt-lake, supposedly towards a ship which would transport them to a POW camp. Instead they were all machine-gunned and buried where they fell.

In 1944, 66 were exhumed and re-interred in a military cemetery at Bari. Traces of the 37 others were found through a private expedition undertaken by Colonel Pietro Giovanni Luzzi during July 2015. In 1946, the German commander of Kos, General Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller, was convicted in Athens for his Cretan war crimes, and executed.

Platáni and the Asklepion

The Greek–Turkish village of Platáni 2 [map] lies 2km (1.2 miles) southwest of Kós Town, on the road to the Asklepion, served in tourist season by a city bus from 8.10am until 10pm (last return slightly before that). Until 1971 it was commonly known as Kermédes (Germe in Turkish), and the Turkish community had its own primary school, but in the wake of the successive Cyprus crises and the closure of the Greek theological seminary in Istanbul, the village was officially renamed and education provided only in Greek. Subsequent emigration to Anatolia has caused Turkish numbers on Kos to drop from about 3,000 to around 700; mainly those Muslims owning real estate and businesses have stayed. Relations between them and their Greek Orthodox neighbours are cordial, and intermarriage is even beginning.

Platáni’s older domestic architecture is strongly reminiscent of styles in rural Crete, from where many of the village’s Muslims came between 1896 and 1912, speaking Greek rather than Turkish; Crete during that period was an autonomous region within the Ottoman Empire, but Cretan Muslims could see that their island would eventually join Greece and that there would be no place for them in the new order. Kos and Rhodes were the closest, similar Ottoman-held islands to which they could flee.

At the main crossroads, with a functioning Ottoman fountain nearby, are several Muslim-owned tavernas, the main reason outsiders stop here, as well as for superior ice cream at the Paradosi sweet shop.

The Jews of Kos

Jews had lived on Kos since antiquity, but the Knights of St John exiled most of this Greek-speaking community to Nice twice between 1314 and 1502. Following the Ottoman conquest, Ladino-speaking Sephardic Jews settled here, their dwindling numbers reinforced after 1922 by co-religionists from devastated İzmir in Anatolia.

Despite this long history, only two tangible traces remain of the Jewish community. On the road between Kos Town and Platáni, a Jewish cemetery lies in a dark conifer grove, 300m/yards from the main Muslim graveyard. Dates on the headstones, inscribed in both Hebrew and Italian, stop ominously in 1940. The remaining local community of about 140, together with 1,973 Rhodian Jews, was shipped to Athens in July 1944 by the Nazis, and thence to Auschwitz for extermination. Just one Koan Jew, who died early in the 1990s, survived the war. The former synagogue, back in town near the ancient agora, re-opened in 1991 as a ‘municipal multipurpose hall’ – it occasionally hosts concerts.

The Asklepion

The Hellenistic Asklepion 3 [map] (summer daily 8am–7.30pm, earlier closure in winter; charge), 4km (2.4 miles) south of town, is one of just three in Greece. The site was first excavated in 1902–05 by islander Iakovos Zaraftis and the German Rudolf Herzog; digging resumed under Italian archaeologists Luciano Laurenzi and Luigi Morricone.

Asklepion ruins

Britta Jaschinski/Apa Publications

Urban bus number 3 or a mini-train make the trip via Platáni between 8.30am and 5.30pm; otherwise you can attempt the steepish bicycle ride, perhaps pausing for lunch in Platáni en route.

The Asklepion (pronounced asklipíon) was actually founded just after the death of Hippocrates, but presumably the methods used and taught here were his. Both a shrine of Asklepios and a curative centre, its magnificent setting on three hillside terraces overlooking Anatolia reflects early recognition of the importance of the therapeutic environment. Two fountains provided the site with clean, fresh water – one still dribbles slightly – and extensive stretches of clay piping are still visible, embedded in the ground.

Today, very little remains above ground, owing to periodic earthquakes and the Knights’ pilfering of site masonry for their castle. The lower terrace in fact never had many structures, being instead the main venue for the Asklepieia – quadrennial celebrations and athletic or musical competitions in honour of the god. Sacrifices to Asklepios were conducted at an altar, the oldest (c. 340 BC) structure here, whose foundations lie near the middle of the second terrace. Just to its east, some Corinthian columns of a second-century AD Roman temple were re-erected by Laurenzini and Morricone. A monumental staircase flanked by exedrae (display niches) leads from the altar up to the second-century BC Doric temple of Asklepios on the topmost terrace, the last and grandest of a succession of the deity’s shrines at this site, though only foundations remain.

Asklepios

Kos’s Asklepion honours the Greek god of healing Asklepios, who according to legend was the son of Apollo and the nymph Koronis. His cult developed from the early Classical era onward, with a half-dozen combination shrines and therapy centres (the biggest at Epidauros) all over the Hellenic world.

The Northeast Coast: Lámbi to Bros Thermá

Kos Town is flanked by two areas of seafront development. Lámbi 4 [map] immediately north is essentially a suburb, albeit one devoted almost entirely to tourism, fringed by a long, east-facing beach (thus the Ottoman name Kumburnu or ‘Sand Point’) liberally sown with beach bars and sunbed concessions. Their biggest concentration is along Aktí Andoníou Zouroúdi, which extends almost up to Mylos, a recommended windmill beach-bar beyond the urban grid. Don’t try to walk or pedal past it all the way to the end at Cape Skandári, as this is an off-limits military base.

The coast road southeast from town, starting at the yacht marina, curls around the northeastern tip of Kos, passing en route much of the island’s luxury accommodation. Psalídi 5 [map] can be said to start at the few spiral-fluted columns of the fourth-century AD basilica of Ágios Gavriíl, just inland from the road in a marshy area. There are a few indifferent public beaches nearby, with sunbed-and-umbrella concessions, but most coastline here is the domain of hotels (aside from near our recommended windsurf schools beyond Cape Loúros).

Beaches can get really busy in the summer

Alamy

Once past the last resort hotel on the strip – Okeanis – Ammos beach bar signals the start of an excellent, much more protected stretch of sand and pebbles extending for over 1,000m (0.6 miles) south to Cape Ágios Fokás 6 [map], with its military watchtower. While there are no facilities aside from Ammos, this patch is popular with locals who come prepared with picnics and umbrellas to enjoy the clean sea here. Discreet naturism is practiced where low cliffs shield the beach from prying eyes up on the road. It’s easy enough to pedal out here on a clunker bike, being only 6km (3.7 miles) from town, mostly on designated, flat cycle path.

The next decent beach is beyond the cape, between it and a final cluster of hotels. There’s another beach-bar here, somewhat regimented, but the shore just east, where some tamarisks lend shade, is protected from most winds. Urban buses numbers 1 and 5 serve this route from dawn until midnight, with eight (between 10.15am–5.15pm, last return 6pm) continuing to the start of the dirt track down to Bros Thermá.

Bros and Píso Thermá

The unusual, remote hot springs of Bros Thermá 7 [map], one of the most popular attractions on Kos, emerge from volcanic cliffs about 3km (2 miles) beyond Cape Ágios Fokás. They are most easily reached by rented vehicle (or for the very fit, multi-speed mountain-bike); the final approach lies along a dirt track heading down and left at a drinks stall just before the end of the asphalt, where buses leave you. Track roughness varies depending on the preceding winter; rent a jeep to guarantee passage. Parking is very limited and you may have to leave four-wheelers a good 300m/yards shy of the springs, certainly no further than the sunbed/snack bar concession which serves the small pebble beach at the bottom of the steep grade.

Enjoying the warm waters of Bros Thermá

Mark Dubin

Scalding, odourless springs (45°C/113°F at source) issue from a tiny grotto at the base of the palisades, flowing through a trench to mingle with the sea at comfortable temperatures inside a giant corral of boulders. Winter storms disperse the boulder wall, re-fashioned every April, so the pool changes shape from year to year – but always has a maximum depth of about three-and-a-half feet. Despite periodic threats of development as a spa, it remains free of access, and immensely popular with tourists and locals alike, especially during the cooler months or on moonlit nights – and under a full moon, it’s truly magic (provided your pool companions aren’t too rowdy!).

About halfway between Bros Thermá and Kardámena, maps show another coastal hot spring at a spot marked Píso Thermá 8 [map], or Agía Iríni after the chapel there. The normally authoritative Greek-language hot-springs guide Ta Loutra tis Ellados claims you can walk there along the shoreline with some difficulty from Bros Thermá in two hours, as does the municipal website www.kos.gr. The Píso Thermá springs were once hotter (47°/117°F) and stronger-flowing than Bros Thermá, but during the 1970s a boulder-fall blocked their main outflow, leaving just a few warm seeps emerging from the seabed. Today people mostly go by boat from Kardámena, especially for the saint’s day (May 5) pilgrimage.

Northwest Coast Resorts: Tingáki To Mastihári

Scattered along the northwest-facing coast of Kos, the resorts of Tingáki, Marmári and Mastihári share an exposure to prevailing summer winds, and great Aegean views. The profiles of (west to east) Kálymnos, Psérimos and the Turkish Bodrum peninsula on the horizon make for spectacular scenery, especially at sunrise or sunset.

Tingáki and Marmári

Tingáki 9 [map] (sometimes ‘Tigáki’), the shore annexe of the Asfendioú hamlets (for more information, click here), lies 9km (5.5miles) west of Kos Town, whether via Zipári and the main trunk road, or by more relaxing back roads preferred by cyclists. It’s a busy, somewhat higgledy-piggledy resort popular with Brits, with most of its accommodation scattered inland among fields and cow pastures. The long and narrow, white-sand beach, fringed at the back by jujube and tamarisk trees, improves, and veers further out of earshot from the frontage road, as you head southwest from the focal seaside T-junction/plaza, with the best patches to either side of the drainage from Alykí salt lake.

Just west of the plaza, Artemis Hamam (daily; www.artemishamam.com), is Kos’s only public, non-hotel-affiliated answer to those across the way in Bodrum. All the usual massages and therapies are available, best enjoyed in discounted packages (€50–120). There’s also a shop with genuine Turkish-made hamam products plus Western lotions and oils.

The traditional coastal annexe of Pylí village, Marmári ) [map], 15km (9.3 miles) from Kós Town along the island trunk road, has a smaller built-up area than Tingáki; its beach is broader and arguably better, especially the section signposted as Píthos. To the west, the sand forms mini-dunes sheltering the odd naturist. A grid of paved rural lanes, popular with cyclists, links the inland portions of Tingáki and Marmári. Arriving along the main road, you turn off just past the little duck-pond and derelict buildings at Linopótis, which began life as the Italian agricultural colony Anguillara. Marmári is most popular with Germanophone and Italian visitors.

Flamingos on the Alykí salt pan

Shutterstock

Alykí Seasonal Lake

Tingáki and Marmári are separated by the Alykí salt pan ! [map], which becomes a brackish lake lasting until next autumn after wet winters. Recent years have indeed been rainy, with flamingos (and the odd swan) arriving as early as October and staying until early June; almost 450 flamingos were counted wading over one week early in 2015. If they aren’t visible here, chances are the wind has diverted them to the smaller, brackish pond near the cape at Psalídi.

Western striped-neck terrapins (Maremys caspica rivulata) often congregate near the seasonal lake’s outlet to the sea, a sluice with a narrow road bridge over it; if they come ashore, feed them at your own risk – they have strong jaws capable of inflicting nasty wounds, or even severing fingers.

Mastihári

Although it has nearby its share of mega-all-inclusive complexes and Kos’s biggest water-park, three-street-wide Mastihári @ [map], draped over a slope rising from the harbour, remains one of the island’s more low-key resorts; it was a permanent village long before tourism times, as well as the historic summer quarters of Andimáhia, 3km (1.8 miles) inland.

Mastihári, 25km (15.5 miles) from Kos Town by the most direct route, is also the ferry port for the shortest crossing to Kálymnos; most of the year there are morning, mid-afternoon and early evening ro-ro sailings (Wed and Sun no midday sailing), keyed more or less to the arrival times of flights from Athens – KTEL buses to or from Kos Town make a stop in Mastihári en route, dovetailing with the comings and goings of the ferry.

While shorter than those at Marmári or Tingáki, the local beach extending to the southwest is broader, with dunes (and no sunbeds) towards the far end. The early sixth-century basilica of Ágios Ioánnis £ [map] (fenced but unlocked) lies about 1.5km (1 mile) down this beach, following the shoreline promenade (look for the enclosure near the Hotel Ahilleos). The basilica is fairly typical of the island’s numerous early Christian monuments, with a row of column bases separating a pair of side aisles from the nave, a tripartite narthex and a baptistry tacked onto the north side of the building. It was excavated during the 1950s by the great Byzantinologist and architect Anastasios Orlandos, but regrettably its intricate floor mosaics are covered in protective gravel.

Andimáhia, Kardámena And Pláka

Visitors inevitably pass through blufftop Andimáhia $ [map], immediately northeast of the airport, but few stop in the village itself as there are no conventional attractions aside from an old restored windmill, kitted out as a museum with sails rigged (though not turning). This is the last surviving mill of more than thirty which once dotted the ridges here and at Kéfalos. You can inspect the inner workings (daily 9am–5.30pm; charge).

Andimáhia castle fortifications

iStock

More compelling is Andimáhia castle % [map], about 4km (2.4 miles) southeast of the village, mostly by a diffidently signposted if paved side-road beginning at an army camp. Enormous when seen from afar, this triangular stronghold of the Knights Hospitaller overlooks Nísyros and Tílos, and would have been a vital signalling link between those islands and the Knights’ castle at present-day Bodrum in Turkey. The originally Byzantine castle was initially used by the Knights as a prison, then modified during the 1490s in tandem with improved fortifications at Kos port citadel.

The fortifications (unrestricted entry) prove less intimidating close up – except for a rather pathetic old man, dressed in mainland evzone costume the likes of which has never been worn on Kos, who accosts all visitors with a loud, barked ‘Tradizionale!’ and demands money to be photographed. A less authentic or edifying spectacle cannot be imagined; nearby villagers are embarrassed by him but, since he is breaking no law, there is nothing to be done about it.

Once past the fake evzone and through the imposing double north gateway, surmounted by the arms of Grand Master Pierre d’Aubusson dated 1494, you can follow the well-preserved west parapet. The badly crumbled eastern wall presides over a sharp drop to ravines draining towards Kardámena. Inside the walls stand two chapels (open): the westerly, dedicated to Ágios Nikólaos, retains a fresco of Ágios Hristóforos (St Christopher) carrying the Christ Child, while the eastern one of Agía Paraskeví, though mostly devoid of wall painting, sports fine rib vaulting springing from half-columns. Gravel walkways, illumination and a ticket booth were installed in 2001 – and never really used except when there’s a summer concert here, arguably the best time to visit.

Kardámena

Some 5km (3 miles) southeast of the airport, Kardámena ^ [map] is the closest resort to it, just pipping Mastihári, and the largest (1,650) coastal settlement outside of Kos Town. Good, though not uninterrupted, beaches stretching to either side, plus a seafront promenade and platía with a few minor Italian-era buildings, are the sum of its daytime charms. After dark there’s a lively bar and club scene, though nothing like Kardámena’s 1990s heyday as designated party resort for younger Brits. There’s a broader profile of visitors lately – especially Russians, young couples and families – and bars with naughty or Brit-centric names like ‘Ten Toes Up, Ten Toes Down’ or ‘Slug and Lettuce’ are now rare if not completely extinct.

The taverna scene in Kardámena

Getty Images

Northeast of the resort centre, the best patch of beach from the standpoint of amenities, no-hassle parking, good sand and access to exceptionally clean sea free of reef or sharp-edged pebbles is in front of Atlantis Taverna, about 1.5km (1 mile) out of town, which rents sunbeds and parasols affordably.

Beaches southwest of Kardámena tend to be scrappier and monopolised by mega-hotels. It is possible to drive back to the main road directly along here without retracing your steps via the airport, but between the Lakitra and Robinson Club resorts, a stretch of rough, steep dirt road is best tackled with a jeep, especially after hard winters.

Pláka Forest

Just west of the airport on the main island trunk road, signs indicate an initially paved turning to ‘Pláka’. The road soon becomes dirt (but always passable) as one descends into the densely forested Pláka & [map] dell. The main attraction here, besides welcome shade, is a thriving population (c. 30) of wild but camera-friendly peacocks – shrieking, flying up into the trees and marching lines of their offspring around. Local feral cats have learned, presumably after some well-aimed pecks from the parents, to leave the chicks alone. It’s a great outing for kids, as the peafowl are not otherwise aggressive.

South-Coast Beaches: Polémi To Kéfalos

Climbing out of Pláka valley back up onto the main island road, and then heading southwest, drivers soon see profuse signage pointing left (south) and down – sometimes sharply down – to the best beaches on Kos. This is essentially one giant, 5km- (3-miles) strip of sand up to Cape Tigáni, but subdivided into separate patches with individual access roads, whose Greek and touristic-English names co-exist on placards. Beyond Ágios Stéfanos and Kastrí islet, Kéfalos Bay extends along another 3.5km (2.2 miles) of sandy beach.

The beach sections, described below from east to west, are all provided with sunbeds, a rudimentary snack/drinks-bar and often a jet-ski franchise. Magic * [map], officially Polémi, is the longest, broadest and wildest section, with a full-service taverna above the car park (for more information, click here), no jet skis and a nudist zone (Exotic) at the east end. Sunny, officially signed as Psilós Gremós and easily walkable from Magic, has another taverna and jet-skis. Langádes (Markos) ( [map] is the cleanest and most picturesque section of beach, with junipers tumbling off the dunes almost to the shore. Paradise, alias Bubble Beach in boat-trip jargon owing to volcanic gas vents in the shallows, is overrated; the sandy area is too small for the crowds descending upon its wall-to-wall sunbeds and tavernas, while boats attached to paragliding and banana-ride outfits, plus the inevitable jet-skis, buzz constantly offshore. Camel (Kamíla) , [map] is the shortest and loneliest of these strands, flanked by weird rock formations (but no humped beasts) and protected somewhat from crowds by the very steep, unpaved drive in past its hillside taverna; the shore here is fine sand, with no jet skis and good snorkelling on either side of the cove.

Uninterrupted sand resumes at Ágios Stéfanos ⁄ [map] peninsula, with beaches to either side; the left-hand (easterly) one, with sunbeds, is backed by a now-abandoned Club Med complex. The sparsely marked public access road to Ágios Stéfanos begins near a bus stop on the highway, cutting through the Club Med grounds. Two triple-aisled, late-fifth-to-early sixth-century basilicas occupy the peninsula. Once the premier early-Christian monuments on Kos, they are now in disgraceful condition. All of the columns have been toppled by vandals since the 1980s, and the rich mosaics which cover the entire floor have either been damaged or covered in a thick layer of protective sand. You’ll need a plastic beach trowel or a thick brush to uncover two peacocks perching upon and drinking from a goblet, or (in the north basilica, next to the baptistry) two ducks paddling about. All that said, Ágios Stéfanos is still the best preserved such complex on the island, and a wonderfully atmospheric spot.

The Ágios Stéfanos ruins overlook Kastrí islet

iStock

The basilicas overlook tiny, striking Kastrí islet, sporting a chapel and a distinct volcanic pinnacle. From the sandy cove west of the peninsula it’s just a short swim away; in spots, you can even wade. The shallow sea here warms up early in the year and stays that way into November, offering the best snorkelling on an island not otherwise known for it, owing to rock formations cutting across the generally sandy seabed. As at Paradise beach, gas bubbles up from the ocean floor.

The main road southwest from here runs behind a serviceable but not spectacular beach, of equal interest to windsurfers and bathers. Resort development here is modest, formerly pitched at budget-conscious Brits a generation or so older than at Kardámena, but clientele is now more mixed, including many Russians. The strip of scattered one- or two-star hotels, low-rise apartments, tavernas and bars ends at Kamári ¤ [map], the far end of the bay and the fishing-port annexe of Kéfalos village overhead. Boat trips may be offered out of Kamári, but probably no further than Bubble Beach and certainly not to Nísyros.

kéfalos – the wild west

The extreme southwestern tip of Kos, a sparsely inhabited monster-head-shaped landmass, is a semi-mythical paradise for island foodies – literally a land of milk and honey, source of the best island cheese, honey and bread. There is just one inland village, Kéfalos ‹ [map], 43km (26.5miles) from the capital and the terminus for buses. Squatting on a flat-topped hill, looking northeast along the length of Kos, Kéfalos has little to recommend it other than a single ATM and a few basic snack bars. Even the Knights’ castle here, downhill beside the Kamári road, is rudimentary – hardly more than a signalling tower – and unimpressive; the Knights abandoned it in 1504. But the village makes a natural staging point for expeditions south into the rugged peninsula that terminates at sheer Cape Kríkello.

The Kéfalos peninsula

The first point of interest is Byzantine Panagía Palatianí, 1km (0.6 miles) south of Kéfalos; a signposted dirt track (passable to ordinary cars) east from the roadside leads to a parking area by a modern church. Just below stands the fenced-off 9th- or 10th-century chapel, built entirely from masonry of an ancient temple.

Some 500m/yards beyond, there’s contrastingly no signage for ancient Astypalaia › [map], the original capital of Kos until abandoned in 366 BC. Your clue is the large, roadside parking area with a dry fountain, opposite an unlocked gate. It’s a two-minute path-walk down to a late Classical amphitheatre with two rows of seats still in place, enjoying a fine prospect over the curve of Kéfalos Bay – a lovely, pine-shaded spot despite the scanty remains of this once-important city.

Immediately past Astypalaia, a paved side-road leaves the ridge road and heads west towards Ágios Theológos fi [map] beach, 6km (3.7 miles) from Kéfalos. Besides the saint’s chapel, there’s an eponymous taverna which takes full advantage of its local monopoly – just stop in for dessert and a drink perhaps. Forays along the dirt tracks to either side – a jeep or dirt-bike is advisable – will reveal secluded sandy coves below low cliffs.

Appealing Ágios Ioánnis Thymianós monastery fl [map] (6.5km/4 miles from Kéfalos), reached by following the paved road to its end, is almost the end of the line for non-4WD vehicles (jeeps can reach Ágios Mámas, 4.5km/2.8 miles beyond, almost at the cape). Set on a natural balcony under two plane trees, the church is locked except during the festival on 28–29 August; it’s a fine picnic spot at other times.

Remote Kavo Paradiso beach

Mark Dubin

The dirt track heading straight south beyond the monastery goes 1.8km (1.1 miles) to a crossroads; turn hard right here and head another 2km (1.2 miles) down to the island’s remotest beach, Kávo Paradíso ‡ [map] (officially Halandríou). Jeep drivers will feel more confident – after a harsh winter one could ground a saloon car in the deep ruts along the last kilometre, though with extra care plenty of small cars make it through. Kávo Paradíso, a vast expanse of sand and clean (if often surfy) sea with a dramatic mountain for a backdrop, is worth the effort; clothing is optional and most years a snack bar with sunbeds operates June–Sept.

The only other notable beaches around Kéfalos are up on its north shore. Limniónas ° [map] (sometimes Limiónas) is 4km (2.4 miles) due north of the village by good road; there are actually two protected sandy coves here (one with sunbeds), separated by an isthmus leading to the little fishing anchorage. Kohylári, further east along the same coast, is too exposed to interest folk other than kitesurfers; for more information, click here for details.

Around Mt Díkeos

The main interest of inland Kós resides in the hamlets on the north slope of Mount Díkeos (the ancient Oromedon). This cluster of settlements, collectively called Asfendioú, nestles amid the island’s only natural forest and provides a glimpse of what Kos looked like before tourism and concrete took hold. They can be reached from the island trunk road via the extremely curvy side road from Zipári, 7.5km (4.6 miles) from Kos Town; a minimally signposted but paved, straighter minor road to Lagoúdi starting about 1km (0.6 miles) further west; or the shorter access road to Pylí from Linopótis pond.

Pylí: New and Old

Just over 13km (8 miles) from Kos Town along the main highway, Linopótis is a sunken, spring-fed pond, alive with ducks and eels. From the junction here, a good road leads southeast to contemporary Pylí · [map], which divides into two districts. In the upper neighbourhood, 150m/yards west of the main square and church, Pigí district comprises a lush oasis with a recommended taverna (for more information, click here) and a giant, sixteenth-century cistern-fountain, the pigí of the name, with four lion-head spouts – the water is excellent and constantly collected by locals.

Pylí castle overlooks old village ruins

iStock

Pylí’s other monument is the so-called Harmýlio (Tomb of Harmylos), signposted near the top of the village en route to Kardámena as ‘Heroön of Charmylos’, a mythical ancient king of Kos. This consists of a subterranean vault (fenced off) with twelve niches, probably a Hellenistic family tomb. Immediately above it, ample masonry of an ancient temple, perhaps dedicated to demigod Harmylos, has been incorporated into the medieval chapel of Stavrós.

Paleó Pylí

Paleó (old) Pylí º [map], just under 3km (2 miles) southeast of its modern descendant, was the Byzantine capital of Kos, inhabited from about the tenth century until the Ottoman conquest. Head there via Amanioú, keeping straight at the junction where signs point left to Ziá and Lagoúdi. The road continues up to a wooded canyon, dwindling to a dirt track beside a trough-spring for local livestock. Some five minutes’ walk uphill from the spring along the track are the remains of a water mill in the ravine just west.

From opposite the trough, a stair-path leads within fifteen minutes to an 11th-century Byzantine castle, whose partly intact roof affords superb views. En route you pass the ruins of the abandoned village, as well as three fourteenth- or fifteenth-century churches. That of Arhángelos, the first encountered, retains substantial fourteenth-century frescoes, particularly numerous scenes from the life of Christ on the vaulted ceiling, including a fine Betrayal in the north vault. Unfortunately it is usually locked following 2012 restoration, but should it be open, make it a priority to pop inside. Outside are the remains of a graceful Latin arcade of a type usually only seen on Rhodes or Cyprus. Rectangular Ágios Nikólaos (unlocked), just south of the route to the citadel, has a Communion of the Apostles in the apse, while Ypapandí, the largest church and nearest the castle, is almost bare inside but impresses with its barrel vaulting supported by re-used ancient columns.

Lagoúdi

From Paleó Pylí, return to the junction in Amanioú and turn right (east) through Konidário, an abandoned Muslim village that’s now a forest reserve and picnic grounds. After 3km (2 miles) you reach picturesque Lagoúdi ¡ [map], with the prominent Génnisis Theotókou church at the village summit. Its interior shelters vivid 1980s frescoes by reclusive iconographer Nikos Vlahogiannis. If he’s still living adjacent, friendly Father Kyriakos will greet you.

Mt Díkeos the Just

‘Díkeos’ means just or righteous in Greek, and local legend asserts that the mountain assumed this demotic name (versus the ancient Oromedon) because it is ‘just’ in directing its abundant waters to flow usefully north to the island’s villages and fields, rather than pointlessly south into the sea.

Evangelístria and Zía

The first Asfendioú village encountered, either heading east from Lagoúdi or going up the curvy side-road from Zipári, is Evangelístria ™ [map]. Beyond the eponymous parish church extends a neighbourhood of low, whitewashed houses, now mostly abandoned following the stampede down to the coast; the remainder have been bought up and restored by outsiders.

Zia is the place to be at sunset

iStock

Further up the twisty road from Evangelístria, Ziá’s # [map] spectacular views and sunsets make it the hapless target of numerous tour buses each evening. Just six people still dwell full-time in the village, but otherwise any building on the main street that isn’t a taverna is a souvenir shop. The only sight is the preserved water-mill on the grounds of the recommended Neromylos Café (for more information, click here).

Mountainous landscape south of Ziá

Alamy

Ascent of Hristós peak

Ziá is the classic trailhead for the ascent of 840-metre (2730ft-) high Hristós peak ¢ [map], by a paltry three metres (10 ft) the second highest point of the Díkeos range. Taking rather less than half a day, this is within the capabilities of any reasonably fit, properly shod person, and offers arguably the best views in the Dodecanese. Except on the date (6 August) of the annual pilgrimage climb, you will see few or no other hikers.

At Ziá’s upper Platía Karydiás, with its fig tree in a round masoned enclosure and Neromylos Café, find the step-path indicated as ‘Dikaios Mountain Kefalovrisi’. Some five minutes up this, you’ll pass the seldom-open Kefalovrisi Taverna, and then onto a dirt track for a few minutes more to Isódia tís Theotókou chapel with its vaulted roof, covered porch and bomb nose-cone hung as the bell. Bear right at the junction behind it – blue arrows guide you, and the surface underfoot is briefly cemented – and head west past Ziá’s last house.

Some fifteen minutes from Platía Karydiás, you pass Ágios Geórgios chapel, locked to protect its frescoes (some visible through the door window). The rough onward track, just passable to vehicles, curls gradually south past one large and one small rural cottage; beyond Ágios Geórgios, a section of path marked by cairns shortcuts a wide bend in the track (though takes time to get through a wire-fastened gate across the path).

Thirty-five minutes above Platía Karydiás, you’ll reach the true trailhead amidst a juniper grove. The spot is fairly obvious; boulders flanking the path have blue paint dots and the word ‘Dikeos’. There’s also a triangular metal sign in Greek Byzantine script (‘Xpictóc’) and just uphill stone cairns and more paint marks.

The distinct trail zigzags eastwards up the mountainside, leaving the junipers within twenty minutes and arriving just over an hour out of Ziá at the ridge leading northeast to the summit. The grade slackens, and several shattered cisterns, once used by shepherds, are seen north of the path.

From the moment the ridge is attained, it’s another twenty minutes maximum to the peak along the watershed, usually just to its north. The little pillbox-like chapel of Metamórfosi tou Sotírou, visible most of the time, stands about 40m/yards northeast of the altitude survey marker; there’s also a small bad-weather shelter nearby, possibly a roofed-over cistern. Just north of this, you can ponder the esoteric symbolism of a giant crucifix fashioned from PVC sewer pipes and filled with concrete.

Turkey’s Knidos Peninsula dominates the view to the southeast; Nísyros, Tílos and Hálki float to the south; Astypálea closes off the horizon on the west; Kálymnos and, on a good day, Léros, are spread out to the north; and the entire west and north portions of Kós are laid out before you.

The south flank of Mt Díkeos takes a steep dive towards the Aegean; those intent on visiting remote Theológos chapel down this slope should engage a qualified local guide. The ridge continuing northeast to the true summit (843m/2740ft) can only be tackled by technical climbers – there are too many knife-edge saddles and arêtes. So the sole feasible descent involves retracing your steps, which takes just ten minutes less than the climb, owing to the rough surface. Allow two hours thirty minutes minimum walking time for the out-and-back trip from Ziá – three-plus hours inclusive of photo and rest stops.

Asómatos and Haïhoútes

The paved road east of Ziá threads through the densest forest on Mt Díkeos – mixed juniper and pine – and also passes two of the more interesting Asfendioú hamlets. Asómatos, with views rivalling Ziá’s (but no amenities), is still home to perhaps thirty villagers plus a handful of foreigners and Athenians renovating houses. The place really only comes to life at the November 7–8 festival of the gaily painted central Arhángelos church, whose spacious courtyard (usually locked) features a fine pebble mosaic.

Haïhoútes ∞ [map], officially Ágios Dimítrios but increasingly referred to by its Ottoman name, lies 2km (1.2 miles) further. It was abandoned entirely during 1967–74, when the villagers departed for Zipári or further afield. Today, there are signs of revival, with eight residents, old-house renovations and a pleasant café operating just uphill from the reliable, potable fountain. In the narthex of the attractive central church, a small photo display documents a considerable population during the 1940s, when the village was a centre of resistance against the occupation.

The road continues another 6km (3.7 miles) to the Asklepion, completing your circuit of the island.

On the ferry

Britta Jaschinski/Apa Publications

Excursions

Kos offers opportunities to visit several Dodecanesian neighbours on separate day-trips, or overnight stays. Catamarans make it possible to design your own itineraries without signing on to organised excursions available from boats moored at Mandráki port.

Closest is volcanic Nísyros on the south, with its caldera and photogenic villages. Northwest lies craggy Kálymnos, once a sponge-divers’ island, and its sleepy satellite islets Psérimos and Télendos, ideal day-trip destinations from Kálymnos. Beyond Kálymnos, Léros merits a visit for a fine castle and 1930s Streamline Modern architecture. Last and remotest, the holy island of Pátmos beckons with its fortified summit monastery and the enchanting surrounding village. You can also pop over to Bodrum in Turkey, whose lights are clearly visible by night northeast of Kos.

Nísyros

In legend Poseidon, battling the titan Polybotes, tore a rock from Kos and crushed his adversary beneath it. The rock became Nísyros § [map]. Hardly less prosaic are the facts of a prehistoric eruption, when this volcano-island apparently blew its top Krakatoa-style. Notably fertile despite lacking water, Nísyros has proven attractive and wealthy enough to keep almost 1,000 permanent inhabitants (down, though, from 5,000 in 1912, and 2,600 in 1947). While remittances from overseas (particularly New York) are vital, most income is derived from offshore Gyalí islet, a vast lump of pumice and perlite slowly being quarried by a score of miners. Rent collected by the municipality from the mining concession funds a public bakery, pharmacy and well-padded civil service. Accordingly, islanders bother little with agriculture besides keeping cows; hillside terraces meticulously fashioned for grain and grapes lie abandoned, and winemaking has ceased.

Day-trips from either Kardámena or Kos Town typically arrive at 10.30–11am, with passengers whisked immediately by coach up to the volcanic caldera in the interior before transfer back downhill for lunch and departure at 3.30–4pm. But visiting just for the day is a pity, as Nísyros fully deserves an overnight or two. Hire a scooter or car from Manos K (tel: 22420 31029) on the port, or trust public buses and your own feet.

The blue balconies and white houses of Mandráki

Britta Jaschinski/Apa Publications

Away from its harbour, Mandráki ¶ [map] proves an attractive, deceptively large capital, with blue patches of sea visible (and audible) at the end of narrow, cat-thronged streets. Brightly painted wooden balconies and shutters hang cheerfully from tall, white houses ranged around a central communal orchard. The well-labelled archaeological museum (Tue–Sun 8.30am–2.40pm; charge) does a gallop, over two floors, through local history, from Archaic grave goods to Roman stelae and Byzantine painted bowls. Overhead, a Knights’ castle (best appreciated from Hohláki beach behind) shelters the earlier Panagía Spilianí monastery with its grotto-like church, built in accordance with instructions from the Virgin herself, who appeared in a vision to an islander. On the way up, the local folklore museum (unreliable hours May–Sept; charge), with traditional paraphernalia and archival photos, is worth a glance if open. During 1996–97, the Langadáki district just below was rocked by multiple earthquakes, damaging numerous houses (mostly repaired).

As a defensive bastion, the seventh-century-BC Doric Paleókastro (unrestricted access), a short walk out of Langadáki, is far more impressive than the Knights’ castle, and one of the finest ancient forts in Greece. You can clamber up onto massive, polygonal-block walls, standing to their original height, using a broad staircase inside the still-intact gateway.

The volcanic zone

As you approach the Lakkí volcanic zone • [map] (12.5km/8miles from Mandráki), a rotten-egg stench greets you as vegetation gradually yields to lifeless, caked powder. The sunken main crater, Stéfanos, is an extraordinary moonscape of grey, brown and jaundice-yellow 260 metres (845ft) across; another, less visited double crater (dubbed Polyvótis), even more dramatic, awaits to the west, created between 1873 and 1888. Steam-puffing fumaroles in the craters accumulate little pincushions of sulphur crystals.

Walking on Stéfanos crater is an exhilarating experience

Britta Jaschinski/Apa Publications

Standing on the floor of Stéfanos (stick to trodden areas, the crust is thin elsewhere) you hear mud boiling away below you – the groaning of trapped Polybotes, for some 45,000 years according to geologists. The most recent eruptions, which produced steam, ash and earthquakes, occurred in 1422, 1873, 1888 and 1933 – the volcano is merely dormant. The Greek power corporation made exploratory geothermal soundings nearby until 1993, when it departed, stymied by islander hostility – though not before destroying the 1,000-year-old cobbled road down to Mandráki.

Four eucalypts shade a drinks kantína in the centre of the wasteland; a ticket booth flanking the access road charges admission to the area in season. The easiest path up to Polyvótis begins along the fence 20m/yards beyond the kantína.

Villages and walks

Two photogenic villages perch above Lakkí. Nearly abandoned Emboriós (pop. 27), with a tiny summit castle, is slowly being bought up and restored by outsiders, who often discover natural saunas in the basements of their crumbling houses; at the village outskirts there’s a signposted public sauna the grotto entrance outlined in white paint. (Most Emboriots relocated to the fishing/yacht port of Pálli after World War II.)

Nikiá ª [map], 13km (8 miles) from Mandráki’s port, is busier, with 61 registered inhabitants and signs of some renovation activity. Its quirky round platía has one café and there’s also a moderately worthwhile Museum of Vulcanology occupying the disused school (Mon–Thu 11.30am–6.30pm, Fri–Sat 10.30am–2.30pm; charge). For most visitors though, the unlocked cemetery chapel of Agía Triáda, with its 15th-century frescoes, will prove more tempting.

Nísyros offers good walks through countryside green with oak or terebinth, on a network of fitfully marked and maintained trails; these are traced correctly on the recommended map. Autumn is a wonderful time, especially for the succulent local figs (the Turks called the island İncirli, ‘Fig Place’).

You can sample the best routes in a single day, by starting with a mid-morning bus ride to Nikiá. From beside the museum, follow a sign downhill, then right, towards eyrie-like Ágios Ioánnis Theológos monastery, then continue north 90min towards Emboriós (there’s 1.3km/0.8 miles of unavoidable road-slogging). After lunch there, head west, starting near the little castle, for 45min to Evangelístria monastery, a major hikers’ junction. Allow time for a detour (2hr return) up the well-marked path to island summit Profítis Ilías (698m/2268ft), with a chapel and views to rival those from Hristós on Kos. From Evangelístria, complete a long but satisfying itinerary by descending 40min to Mandráki, via little 18th-century Armás church, with vivid frescoes, the best easily accessible ones on Nísyros.

Beaches and baths

Hohláki, reached by masoned pathway, lies 10min beyond Mandráki – a prime sunset-watching venue, but the sea can be choppy and the coarse pebbles aren’t very comfortable. The sandy beach extending east from Pálli is more user-friendly, with a few tamarisks for shade. Halfway between Mandráki and Pálli, the Dimotiká Loutrá (Public Baths) were refurbished in 2015 with quality marble tubs (unpredictable hours; 20-min soak for a charge). Upstairs is a basic inn, and at the corner of the building a sympathetic if pricey ouzerí. The only other thermal pool on Nísyros is in front of Mandráki’s Haritos Hotel (€5 charge for non-guests).

Nísyros’s longest, best, cleanest and least windy beaches lie on the east coast, 9km/5.5miles from Mandráki. Sandy Liés marks the end of the road, with a summer (late June–early Sept) snack bar and parking area. From there a 15-minute trail past volcanic-ash cliffs leads to Pahiá Ámmos q [map] (Fat Sand), exactly that – 300m/yards of grey-pink stuff heaped into dunes behind, limited shade at the far end, and a constituency of naturists and free campers.

Kálymnos

First impressions of Kálymnos w [map], northwest of Kós, are of an arid, mountainous landmass with a decidedly masculine energy in the main port town of Póthia. The former dominant industry, sponge-diving, has now been supplanted by tourism and commercial fishing. But the island’s prior mainstay is evident in home decor of huge sponges or shell-encrusted amphorae, and souvenir shops overflowing with smaller sponges.

Kálymnos essentially consists of two cultivated, inhabited valleys sandwiched between three limestone ridges, harsh in the full glare of noon but magically tinted towards dusk. The climate, especially in winter, is alleged to be drier and healthier than on its neighbours, since the quick-draining limestone strata, riddled with many caves, doesn’t retain much moisture. Kálymnos’s position and excellent harbours ensure that it has always been important – especially during Byzantine rule, which left many ruined basilicas here. Another Byzantine legacy is the survival of peculiar medieval names (Skévos, Sakellários and Mikés for men, Themélina, Petránda and Sevastí for women), found nowhere else in Greece.

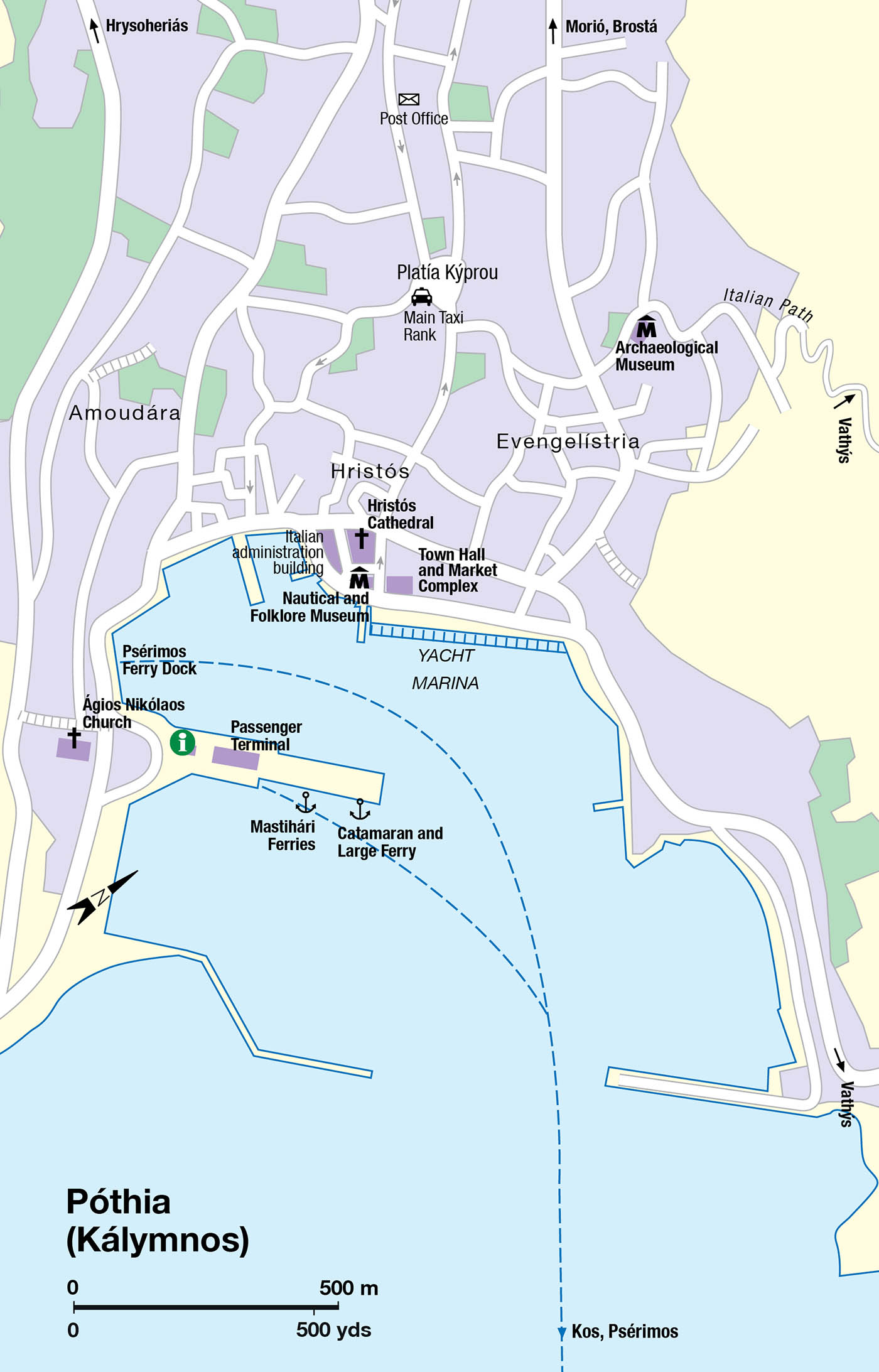

Póthia’s town hall

Mark Dubin

Póthia and around

Póthia e [map] itself (population 12,324), the third-largest town in the Dodecanese, is noisy and workaday Greek, its brightly painted houses rising in tiers up the flanking hillsides. Mansions and vernacular dwellings with ornate balconies and wrought-iron ornamentation (an island speciality) are particularly evident in Evangelístria district. Florestano di Fausto’s 1926–28 administration building and Rodolfo Petracco’s 1934 town hall and market complex bracketing Hristós church deserve a look.

The most dazzling conventional attraction is the Archaeological Museum (Apr–Nov Tue–Sat 9am–4pm; charge). Stars of the displays include a huge Hellenistic cult statue of Asklepios; an unusual robed, child-sized kouros (most were naked); and a life-size third- or second-century BC bronze of a clad woman with her right hand raised in admonition, retrieved by fishermen in 1994 and inevitably dubbed ‘The Lady of Kálymnos’.

The Nautical and Folklore Museum (Mon–Fri 10am–1.30pm; charge for Folklore section), on the seaward side of Hristós cathedral, contains fascinating photos of old Póthia (no quay, jetty, roads, or sumptuous mansions in the 1880s) and equipment from seafarers’ lives, including ingenious, dart-shaped nautical-mile logs, dragged off the stern; dangerously primitive divers’ breathing apparati; and wicker ‘cages’ to keep propellers from cutting air lines, a constant hazard.

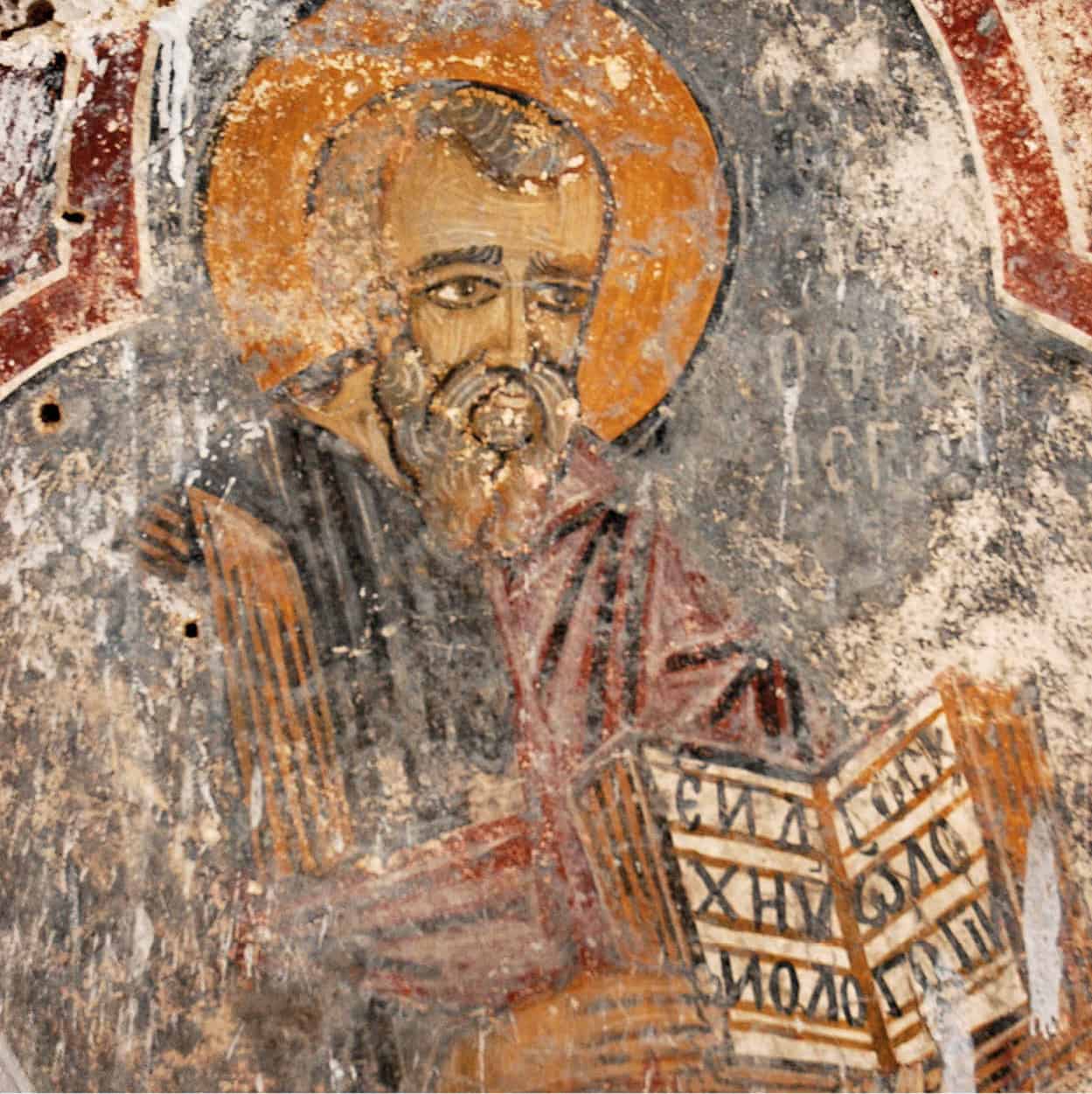

Hrysoheriás castle fresco

Mark Dubin

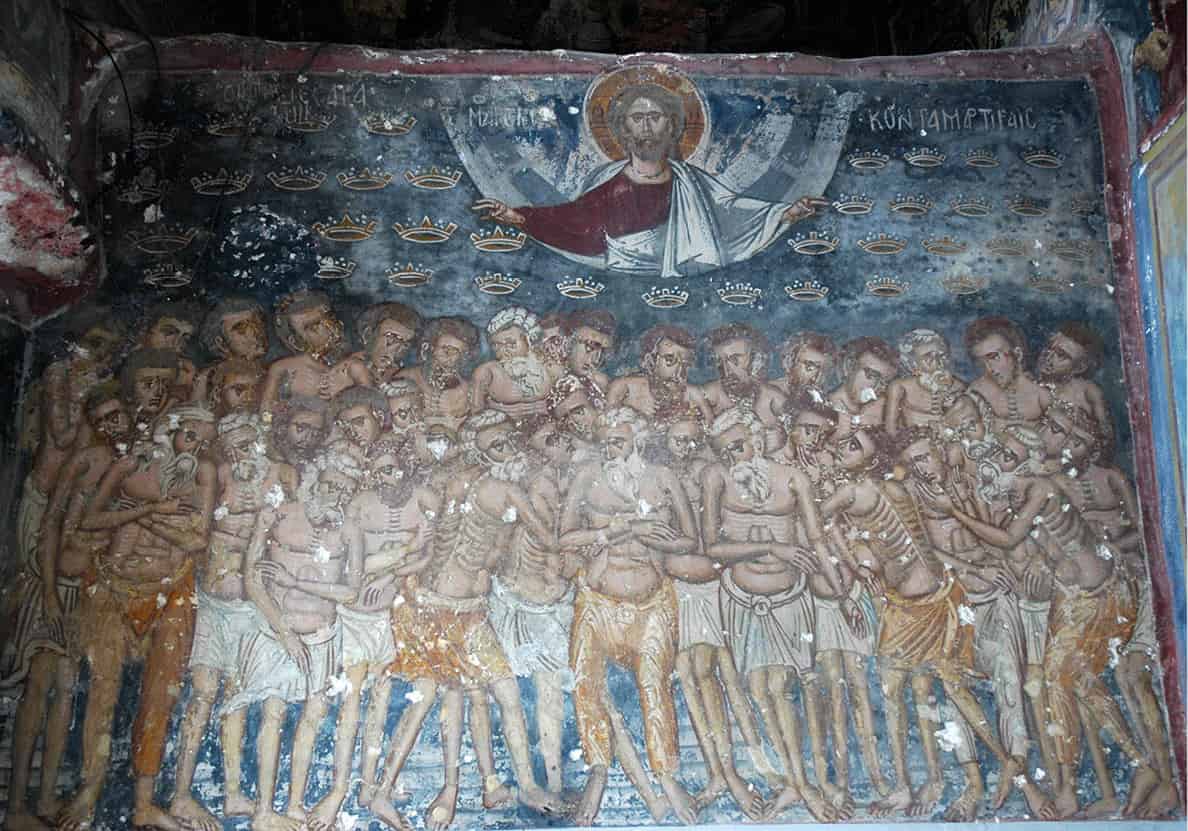

Northwest of Póthia loom two castles (daily all day; free): Hrysoheriás, the Knights Hospitaller stronghold adapted from a prior Byzantine fort, where the views appeal more than anything inside, and the purely Byzantine castle of Péra Kástro above Horió, still Kálymnos’ second town. Although this pirate-proof citadel was inhabited until the late 1700s, there are few standing structures inside besides several unlocked churches offering fragmentary 15th- or 16th-century frescoes.

West from Horió, some 200m/yards past the airport road, stand the two most intact, and easiest found, of Kálymnos’ Byzantine basilicas. Whitewashed steps lead over a stone wall to Hristós tis Ierousalím (Limniótissa) basilica, supposedly built by Byzantine Emperor Arkadios (395–408 AD) in gratitude for deliverance from a storm, though sixth-century construction is far more likely. The ornate apse with bishops’ throne is fully preserved, as are sections of marble flooring; both incorporate inscribed masonry taken from a Hellenistic Apollo temple nearby. One field east, reached by a separate path from the road, is larger, three-aisled but less impressive Agía Sofía basilica; again the apse is the best preserved bit, used as a chapel after the rest of the complex was destroyed during 7th-century Arab raids.

Vathýs and Beyond

The main sight northeast of Póthia is Vathýs r [map], the island’s main oasis, 11km/miles away by road. The first stretch is grimly industrial, passing a boatyard, a power plant, tank farms, quarries and a rubbish tip. None of this prepares you for a sudden road-bend and dramatic view to Vathýs far below, its green contrasting sharply with the mineral grey and orange uphill. This long, fertile valley, carpeted with walled orange and tangerine groves threaded by a maze of lanes, seems a continuation of cobalt-blue Rína fjord penetrating the landscape here. Rína itself is popular with yachties and accordingly has a clutch of overpriced tavernas at the head of the port, but no beach.

Without a vehicle, the best (and a popular) way to reach Vathýs is by hiking along the old cobbled trail from beside Agía Triáda church in Póthia’s Evangelístria district, arrowed conspicuously on a wall as ‘Italian path’. It takes an hour to reach the pass (400m/1,312 ft elevation) in the ridge overhead, and another forty minutes downhill to Plátanos hamlet in the oasis.

Once at Plátanos, collect water from the potable spring under the namesake plane tree and ponder a continuation. You can loop back to Horió on a major trail around the shoulder of Profítis Ilías (676m/yards), descending a scenic gorge, or carry on from Metóhi hamlet with its frescoed Taxiárhis chapel to the start of the two-hour path to Arginónda (with some brief road-walking in the middle). Have lunch and a swim in coastal Arginónda, then catch a bus back to town – you may have to road-walk 5km (3 miles) to Armeós to get one. All these routes are detailed accurately on the recommended Anavasi map.

Brostá: The West Coast

The consecutive beach resorts on the west coast are referred to collectively by islanders as ‘Brostá’ (Forward), the leading side of Kálymnos, as opposed to ‘Píso’ (Behind), the Póthia area.

Kandoúni t [map] attracts mostly Greek and local clientele, the latter owning summer villas here; the beach – 200m/yards of brown, hard-packed sand – isn’t brilliant. Especially towards sunset, take the obvious coastal path southwest to the little monastery of Ágios Fótis (80min return hike), offering seascapes, cliffs and a ravine.

Smaller Linária cove, just north of Kandoúni bay, has better sand, tavernas and cafés, plus separate road access. Walk around the corner (or again distinct vehicle access) to Platýs Gialós beach, opposite Agía Kyriakí islet, with Kálymnos’s best sand; a pity the sea is often turbid.

The main road, descending in zigzags, meets the sea again 8km (5 miles) from Póthia at Melitsáhas and Myrtiés y [map], which share Kálymnos’ much-diminished beach-tourism trade with Masoúri and Armeós, just north but reached by an upper bypass road, part of a circular one-way system. Melitsáhas and Myrtiés have the best beaches and cleanest sea, but these contiguous resorts have partly reinvented themselves to host spring and autumn rock-climbers.

Beyond Armeós, the road mostly hugs the coast en route to Emboriós u [map], end of the line 20km (12 miles) from Póthia. This has average tavernas, a mixed bag of beaches to either side (some only path-accessible) and late-afternoon taxi-boat service back to Myrtiés. Buses beyond Armeós are rare, but Kálymnos is ideally explorable by scooter; the only rental outlet in Póthia is Auto Market near Ágios Nikólaos church (tel: 22430 24202, www.kalymnoscars.gr).

Snail or princess?

Legend asserts that the mountainous bulk of Télendos, viewed at dusk from Kálymnos, is the petrified reclining head of a princess, gazing out to sea following her unhappy affair with the mythical prince of nearby ancient Kastélli. The less romantically inclined will only see the silhouette of a snail.

Telendos,as seen here from Kalymnos heights,is popular with rock-climbers – and it is clear why

iStock

Télendos

These resorts’ most appealing feature is the striking islet of Télendos i [map] opposite, which frames some of the Aegean’s more dramatic sunsets. Home to 45 winter inhabitants, Télendos is car-free and tranquil, though tourism (including rock-climbing) has certainly arrived, via little taxi-boats crossing the straits from Myrtiés jetty (daily half-hourly 8am–11pm). Télendos was sundered from Kálymnos by the cataclysmic 554 AD earthquake; remains of a submerged town lurk at the bottom of the channel, sixteen fathoms down.

The single waterside hamlet huddles under Mount Ráhi (459 metres/1,492ft). Halfway up the north side of the mountain, an hour’s trek away by paint-marked path, perches the fortified chapel of Ágios Konstandínos, with excellent views. Less energetic souls explore the ruined Byzantine basilicas of Ágios Vassílios and Agía Tríada at the northern and western edges of the hamlet.

Beaches vary in consistency and size; a long, sandy, tamarisk-shaded one stretches north of ‘town’, while scenic Hohlakás, 10 minutes west, has coin-sized pebbles (and sunbeds) on two separate bays, as do three smaller coves beyond the sand beach, with usually clean water: Pláka, Pótha and Paradise (naturist, 20min away).

Psérimos

Kálymnos’ other satellite islet, Psérimos o [map] (permanent population 35), is an idyllic place once the daily crop of trippers leaves sandy Avlákia bay, with only cicadas in the huge communal olive grove to break the stillness. Excursion boats from Kos operate ‘three-island’ tours (€25–30) which spend just one hour at Psérimos before pushing on to nearby Pláti islet (1 chapel, 1 villa) for more swimming before a rushed lunch on Kálymnos. We don’t recommend these tours, and the only way to spend a whole day on Psérimos – well worth it – is to depart from Kálymnos daily at 9.30am on the little ro-ro ferry Maniaï, returning at 5pm (€10; 55min journey each way). The islanders themselves use this boat for shopping and administrative business; there is only a primary school on Psérimos. During summer, one speedboat per day also calls from Mastihári on Kos.

Grafiotissa beach,Pserimos

Mark Dubin

West-facing Avlákia, the port and only village (including several tavernas), is fronted by a magnificent sandy beach where most trippers park themselves. For those with six hours to spend on Psérimos, there are two other, remoter beaches: clean Vathý (sand and gravel), a well-marked, thirty-minute path-walk east of Avlákia, or idyllic all-sand Grafiótissa beach to the northwest.

The path there starts from the northwestern-most house in Avlákia; go anticlockwise around its perimeter fence to see a light-green paint arrow pointing right towards an obvious trail, which passes between a prominent tree and a concrete survey marker, over a low ridge. The way becomes increasingly obvious, with more green- or white-painted arrows, dashes and blobs to dispel doubt. Allow just over half an hour to reach the ruined old church of Panagía Grafiótissa (festival Aug 14–15), chopped in two by the sea, with just the apsidal half clinging to the low cliff. Nobody alive today on Psérimos can remember a time when it was intact. The modern replacement church just inland has a rain cistern with a bucket for water emergencies. The beach below – a vast expanse of blonde sand lapped by sea of a near-Caribbean hue – is the whole point. There’s some reef offshore, but nothing that impedes entry; Pláti baffles the prevailing wind and occasional swell.

Italian Architecture in the Dodecanese

Italian rule left a significant architectural heritage, long neglected but recently appreciated and restored. These structures are often wrongly dubbed ‘Art Deco’; while some display Art Deco traits, most are Rationalist or Streamline Modern. These schools emerged from early-1900s artistic and political trends, particularly Futurism, Fascist-inspired Novecento Italiano and the 1909–13 ‘Metaphysical Cities’ series of painter Giorgio di Chirico (1888–1978).

During 1924–36, Italy attempted to combine Rationalism and real or imaginary vernacular elements into a generic Mediterranean architecture. Each Dodecanese got at least one specimen in this ‘protectorate’ synthesis, usually the police station or post office, but only four important islands (Rhodes, Kos, Kálymnos, Léros) experienced comprehensive urban re-ordering.

Kos and Kálymnos received a Foro Italico (administrative complex) in neo-Crusader style. Fascist theory also required a square for rallies (on Kos, Platía Eleftherías). 1936–41 was marked by intensified ideology and reference to the islands’ Latin heritage (the Romans and their purported successors, the Knights Hospitaller). This entailed ‘purification’, removing orientalist ornamentation and replacing this with poros stone cladding. Additionally, severity and rigid symmetry – as in the Orthodox cathedral on Kos – was stipulated. Otherwise, Kos was curiously exempt from purification.

Léros

Well-vegetated Léros p [map], with its half-dozen deeply indented bays, looks like a jigsaw puzzle piece gone astray. Lakkí Q [map], the biggest, deepest inlet and large-ferry port, is graced by one of the world’s largest Rationalist-Streamline Modern planned towns, designed as ‘Porto Lago’ by Rodolfo Petracco and Armando Bernabiti and erected during 1934–38 for the officers (and their families) of the huge nearby Italian naval base. The striking, photogenic, renovated buildings here include the round-fronted cinema, the market hall with its clock-tower and circular atrium, the arcaded primary school, and the angular church of Ágios Nikólaos.

The Italian legacy in Lakkí

Mark Dubin

Lakkí’s present population of 2,058 (a quarter of Léros’ inhabitants) rattles around the underused streets; nautical flavour is imparted by yacht marinas and dry-docks, here and at adjacent Teménia. The atmosphere was long weighted by three hospitals for disabled children and mentally unwell adults, though these institutions have mostly closed and the facilities partly occupied by the University of the Aegean’s nursing faculty.

The rest of Léros is more conventionally inviting (easily toured by scooter), particularly the fishing/yacht port of Pandéli, with its fine-pebble beach and waterfront tavernas, just downhill from the capital of Plátanos, its pastel-hued vernacular houses draped over a saddle. Overhead looms a well-preserved Knights’ castle (daily 8am–1pm and 4–8pm; charge) sheltering an excellent ecclesiastical museum (the English-speaking warden gives an engaging tour). The summit views, especially southeast at dusk, are superb. South of Pandéli, Vromólithos W [map] has the best easily accessible and car-free beach on an island lacking good, sandy ones. Elsewhere, sharp rock reefs must often be crossed entering the water. Southeast of Vromólithos, two sandy coves at Ágios Geórgios are less crowded.

Picturesque Agia Marína E [map], beyond Plátanos, is the usual excursion boat and catamaran harbour (though catamarans often dock at Lakkí). It has several tavernas and cafés, plus more whimsical Italian monuments like the market hall and customs house.

Álinda and around

Álinda R [map], 3km (2 miles) northwest along the same bay via Krithóni, is Léros’ oldest established resort, with a long pebble beach right by the road – quieter swimming is available east around the bay at Panagiés and Dýo Liskária (taverna-café). In a walled enclosure at Álinda’s south end, a poignant, immaculately maintained Commonwealth War Graves cemetery contains 184 casualties of the Battle of Léros.

The other Álinda sight is the Folklore and Historic Museum, housed in the unmistakable Bellenis castle-mansion (May–mid-Sept Tue–Sun 9am–1pm and 6–8pm; charge). Many displays pertain to the battle: relics from the sunken Queen Olga, a Junkers bomber-wheel, a stove made from a bomb casing. There’s also a rather grisly mock-up clinic and assorted rural impedimenta, costumes and antiques. One room is devoted to Communist artist Kyiakos Tsakiris (1915–98), interned locally by the junta, his works executed on stones, shells and wood. Photos recall vanished monuments: a fine market hall in Plátanos demolished in 1903, and a soaring medieval aqueduct at the Kástro destroyed during the 1943 battle.

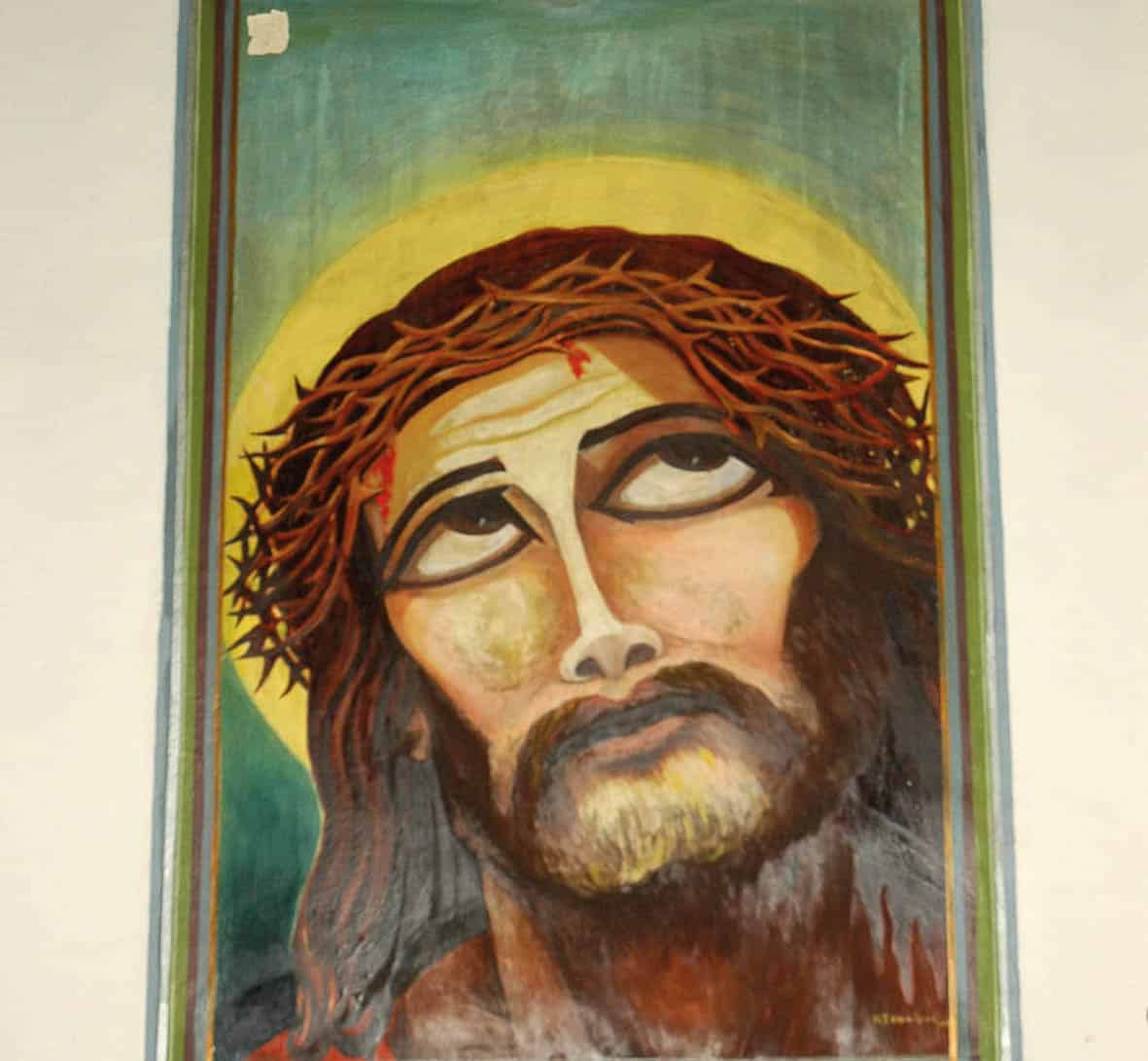

A controversial mural at Agía Kiourá

Mark Dubin

Remote Sites

In antiquity Léros was sacred to Artemis, though her temple is lost somewhere near the airport – definitely not the signposted foundations of an ancient fort. Artemis’ reputed virginity survives in the place-name Parthéni, past the airport: an infamous political prison during the 1967–74 junta, now a grim army base, as it was in Italian times. Things perk up beyond, at Blefoútis beach (taverna), plus the hilltop chapel of Agía Kiourá T [map] (always open), decorated by Tsakiris and two other junta-era prisoners with strikingly heterodox murals of Christ’s Passion and the Apostles, which the mainstream Church has always loathed – they are legally protected from further erasure.

Other bays tend not to be worth the effort. West-facing Goúrna has a long, sandy and gently shelving (but also windy and often dirty) beach. Isolated, southerly Xirókambos refuses to face the fact that its scrappy beach hinders its chances of becoming a proper resort; caiques ply to and from Myrtiés (Kálymnos) daily in season, but it’s better to continue to Pandéli (four times weekly). For more variety in swimming spots, take a day cruise (11am–7pm; €25–30) with the Barbarossa, moored at Agía Marína, to various islets northwest of Léros.

Léros War Museums

The Merikiá Tunnel Museum (daily 9.30am–1.30pm; charge), occupying the former Italian naval command centre, displays abundant, barely labelled documents and military hardware; histrionically narrated archival footage tries to explain everything. Either Ioannis Paraponiaris’ Deposito di Guerra in remote Agía Iríni, or Tassos Kanaris’ private collection in Plátanos, makes better viewing; guided tours only, easiest arranged through Léros Active in Agía Marína (tel: 22470 24590). The massive Italian radio-command buildings at Ágios Nikólaos are unlocked, with Nazi insignia painted on the walls inside.

The Battle of Léros

Across Léros bomb nose-cones and shell casings serve as gaily painted courtyard ornaments or gateposts – evidence of the 1943 Battle of Léros. The British landed forces on 13 September, who (together with the existing Italian garrison) attempted to hold Léros. Over 52 days from 26 September – when the destroyers Intrepid (British) and Queen Olga (Greek) were sunk at Lakkí – the Germans bombarded the island with 1,369 air-sorties from Rhodes and Greece’s mainland. Besides ‘softening up’ British Commonwealth HQ at Merovígli above Plátanos, a principal objective was to knock out monstrous, hilltop Italian guns, whose range of ten nautical miles made approach by sea impossible.

Finally, on 12 November, the Germans began landing both para-troops and fighters shipped to the northeast coast, where Allied gunnery sank two landing craft. An unusually warm autumn created even more hellish conditions. German mastery of the air made resupply of the island impossible, and ensured the Allied loss of Léros. On 16 November, the British commander surrendered, with 8,500 Commonwealth and Italian soldiers taken prisoner. Casualties on all sides were horrendous – 80 from the Queen Olga’s crew; about 400 Italians, from their force of about 8,000; about 600 Commonwealth, out of roughly 3,000; and 2,600 Germans (most lost at sea).

Pátmos

Pátmos Y [map] has been synonymous with the biblical Book of Revelation (Apocalypse) ever since tradition placed its authorship here, in AD 95, by John the Evangelist. A volcanic landscape, with evocative rock formations and sweeping views, seems suitably apocalyptic. In 1088 the monk Hristodoulos Latrenos founded a Patmian monastery in honour of St John the Theologian (as John the Evangelist is known in Greek; Theologos is a common island male name), which soon became a focus of scholarship and pilgrimage. A Byzantine imperial charter granted the monastery tax exemption and the right to engage in trade, concessions respected by later overlords.

The Monastery of St John the Theologian on Pátmos

iStock

Although the monks no longer rule Pátmos, their presence tempers potential resort rowdiness. While there are some naturist beaches, nightlife is genteel, and the clientele upmarket (including the Aga Khan’s family, plus various ruling or deposed royal families). Those who elect to stay overnight appreciate the unique, even spiritual, atmosphere that Pátmos exudes once day-trippers and cruise-ship patrons have departed.

Skála U [map] is the port and largest village (1747 out of 3047 islanders), best appreciated at night when crickets serenade and yacht-masts glow against a dark sky. By day Skála loses its charm, but all island commerce is based here. The modern town dates only from the 1820s, when the Aegean had largely been cleared of pirates, but at the summit of the westerly rise, known as Kastélli (signposted), lie extensive foundations of an ancient acropolis.