prologue

The end doesn’t depend on the beginning, it upends beginnings, also provokes new ones. If the end comes, it’s to one person, and could spark beginnings in others.

The beginning starts in history, not as a single event, though every birth is singular, and every death, also, but death and birth repeat themselves, the way history does, until no one remembers. —Ezekiel H. Stark

self-narration, or wildness of origin myths

The universe heaves with laughter, and I’m all about my lopsided, self-defining tale. How I came to be me, not you, how I’m shaping me for you, the way my posse and other native informants do for me, how I’m shape-shifting. I’m telling you that I’m telling you; my self is my field, and habitually I observe, and write field notes.

Ethnographer, study yourself. Ethnographer, heal yourself.

There was a no-time, with time outs—a long time ago, Way Before Now. Space and time, on a continuum, bend in relationship, and I imagine that soon I will, in some sense, return to the past. Whenever I want.

Routine settles, creeps in: I’ve performed the same acts for thirty-eight years, like eating breakfast. You were eating breakfast, you have been eating breakfast, you are conjugating breakfast ever since your mother set food before you, and now you’re feeding yourself only if you shop for it, or maybe you went back to the land to raise it, but not everything, you don’t and can’t raise everything. I was damn fortunate: meals appeared regularly, I’m no ingrate. That was part of “my home.”

You were spoon-fed, and it landed plop on the floor, or you the baby threw it. Bad boy. Throw a tantrum, make a mess, soon you have to clean it up—break it, buddy, it’s yours, in pieces, because you are responsible; and, true, things go to pieces when not actually broken. Abstractions get broken. Ideas get broken. I have seen the best minds of my gen . . .

Me talking ’bout the flawed life, totally.

Going to sleep, that gets tired, ha, the regularity, and boredom might cause my chronic insomnia, so it’s cool when you don’t know you’re falling asleep, then you wake up and the TV is on. You open your eyes, weird. To dream becomes the best reason to sleep, especially if you do (I do) conscious dreaming, and get to choose: a dream becomes a podcast or movie. Otherwise, nightmares pit REM sleep

with terror.

I listened to a podcast of an old TV news program and heard a Soviet and Russian historian, Stephen Cohen, argue with a total jerk. Completely exasperated by the fool, Cohen finally said, “With all due respect, you don’t know what you’re talking about.” I swallowed the moment like a hallucinogen. That’s so fucking rare . . . it tears up Max Weber’s cage.

That’s my goal, to tear it up. Me, especially.

I don’t get high anymore, antidepressants keep me sort of level, and don’t combine well with recreational drugs. Living drug-free is a sort of high, except clarity can get ugly.

My analyst suggests that I elongated my kid-hood by delaying leaving home. No big deal, really typical.

I suffer from abulia, which my analyst says is an abnormal lack of ability to act or make decisions. I like the word. So, I say to my analyst, “Abulia . . . I’m another Hamlet. Look what happened to him.” I dither, weigh both sides, make lists, advantages, disadvantages.

My mother was a permissive parent, finishing college in the mid-sixties, and didn’t want to parent like her uptight parents who let her know she was on her own. Mother had a small trust fund from her maternal grandmother, and did an M.A. in English, then met a man who became her husband, my father, and started a family, as they put it. Father didn’t drink then, I mean, excessively. They had us, spacing Bro Hart and me, then an accident—Little Sister—she had to have been. Father, I don’t know what his wishes were, but I don’t think he fulfilled something in himself. Anyway, he became a functional drunk; Mother kept loving him, maybe. Takes all kinds. He was absent for me, hooked up to his necessaries, like to a breathing machine. I’d come home after school or tennis lessons, walk over to the couch, and his watery eyes were just pools.

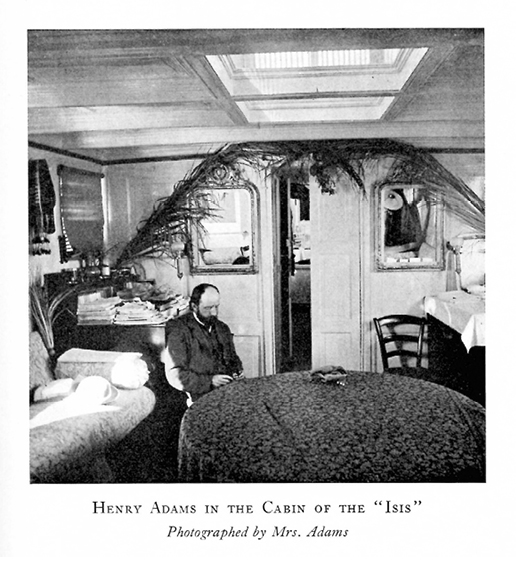

Staring at photographs of him when he was young, when I was young, comforted and bothered me. Here was evidence of a bright-eyed guy beside the dull living person I knew, and it was discrepant, though I wouldn’t have said it like that then, couldn’t put the two together, it didn’t compute that the boy had turned into this man, my father.

In childhood, desires and passions are seeded. In adulthood, they flower into interests and manias.

picture: me in a frame (framed)

My frame of reference is cultural anthropology. Clifford Geertz says that “doing ethnography is like trying to read (in the sense of ‘construct a reading of’) a manuscript . . .”; that “culture is public because meaning is.” I do ethnography by working with photographs; also with the human absorption in images, and with the many forms and senses of image, creating an image, loving an image, etc. My specialty—

family photographs.

Images don’t mean as words mean, though people (and I) apply words to them.

Photographs can create images, but they are not images per se, they are things, a physical object. An image doesn’t have to be based on a photograph. It is a mind-picture, or an image is a picture in the mind. A photograph may inspire or foment an image or images. An image is a concoction, often manufactured, meant to create a way to be seen, viewed, understood. It can be aerie faerie, a phantom, phantasm.

Can an image built out of self-consciousness lie?

I wear a brimless hat, because it’s cool. Does it tell a lie about me?

I take a photograph, I don’t take an image.

(Unless I’m a vampire. Haha. Vampires don’t look like the ones on TV, the living dead are regular people, who suck you dry.)

A mind is not a brain. Or, a brain is to a mind what a photograph is to an image. And they can be conflated, brains and minds, images and photographs, and sometimes I do

it too.

Virginia Woolf—Mother’s fave—says that words also can’t be pinned down: “[Words] do not live in dictionaries . . .

they hate anything that stamps them with one meaning or confines them to one attitude, for it is their nature to

change . . . It is because the truth they try to catch is many-sided, and they convey it by being themselves many-sided, flashing this way, then that. Thus they mean one thing to one person, another thing to another person.”

But a photograph doesn’t own even a wayward dictio-nary, though semioticians work it, finding ways to read one. Even vertiginously, words have definitions, to name and rename objects in a cascade of tautologies. A synonym loops, loop de loops.

The antique game of telephone: the last to hear, in a string of listeners, will have (hear) an entirely different story from the first.

Looking can be benign or malevolent; looking entails everything human, and our instinct to look keeps us close to our evolutionary partners and antecedents in crime and development. If a deer spies a human, it will determine its level of threat. A deer runs if an unknown creature gets closer than what it perceives as safe. And deer are stupid, nice to look at but dumb as doors.

Now, people are stealthier in their observations, but the same principle applies: the need to clock others. A stranger enters a room, a group of familiars note her or him, no one moves, a second, thirty seconds pass until one brave familiar strides across the floor, to the door. The stranger introduces himself, and the familiar brings the stranger into the room, and soon others come closer and sort of sniff him. If no one moves toward the door: stasis, unless the stranger boldly enters and quickly identifies himself—I’m Michael, Donald’s friend. Imagine if the person entered but didn’t identify himself. Discomfort would be fierce.

Who is a perfect stranger? Is there a “complete stranger”?

Humans assess others shoddily, errors in judgment they’re called. People can be poor at sniffing out an enemy, lack discernment, even common sense, and fail at comprehending dangers, signs. Supposedly our big brains allow for more choice, for being sensible, and are capable of complex thinking, etc. Other theorists work diligently on this problem; for one, economists, who analyze rational and irrational consumption patterns.

Just saying, as a person who studies groups: people fall in love with the wrong people, make the wrong friends, trust the wrong bank manager, and associate with hurtful, vengeful people.

Wolf families have a scapegoat; no wolf picks on any other wolf except an outsider (exogamous) male who tries to pick off the pack’s females or eat its cubs. A fight happens then, often to the death. Otherwise, it’s the scapegoat who’s pushed around. He or she eats last, even when he’s the brother, say, of the alpha who eats first. No mercy for a scapegoat.

In human groups, scapegoats exist to keep the tribe united.

Call human scapegoats “victims.”

Generally, people drop imprecise clues. Unlike other animals that mark territory with piss or rub scent on trees, human displays or signs can mystify, at least be ambiguous. The worst, the most troubled and damaged, might be the best at keeping their worst signs on the down low. Yet an extremely foul-smelling human on a train clears the car. Imagine if untrustworthy lovers gave off a specific odor.

A traditional sign, the wedding ring, signifies as few contemporary interpersonal and social signs do. But it also has scant weight in some Western circles and might even encourage a “free-ranging” male or female to pounce onto someone’s spouse. No consequences. Haha.

When I was fifteen, I met a philosopher, ninety years old, and, half-kidding, asked him, “You’re a philosopher, so, what do you think about?” He was kind to a smart-ass high school boy, answered seriously, I thought, with a twinkle in his eye, because I don’t know what else to call it—a glint? The philosopher repeated my question, seemingly asking himself: “What do I think about? Love. I think about love, I always think about love.”

Love—platonic, romantic, sexual—appears in human–

animal stories, and mine. A common trope, the love dope. Kidding. The grand passion, l’amour fou, mine is long running and deep, if mad love can run the distance. No kidding.

People repeat themselves, usually don’t know it, and I hate repeating myself (but if I didn’t, who would? Kidding), but no one is considered herself, himself, without doing it. Consistency = repetitive behavior. A groove grinds itself into the brain, a beat or melody runs the neural pathways. On repeat, repeat, repeat. The most popular songs, the most repetitious: “All about that bass, ’bout that bass.” Can’t stop singing it.

The mind fuck.

Does the way you fall in love /

go the same way /

love on repeat or replay?

Similarly, family attitudes, though they aren’t obvious like rhythms and lyrics, get beat into us. Neurosis and Love are grooves, and they get deeper.

family matters

I began life, comfortably.

The family lived in a large 1960s pseudo-architect modernist ranch-style house: five bedrooms, parents on one end (and Mother’s office), children the other side, bedrooms of same size for Bro Hart and me, but Little Sister—hers had more windows, sore point—and walls of picture windows in the living and dining room areas, slate floors, an open kitchen with an island, floor-to-ceiling stone fireplace, and we were sort of in the country. Outside Boston, near Beverly. John Updike territory. Nice family place, if you didn’t know the family. Just kidding.

Mother—Ellen Hooper Stark—edited manuscripts, histories, political science, biographies and memoirs, of intellectuals, she said. I was about seven when she explained it. Little Sister was one and a half, not yet talking, weird for a girl. (The term then was “delayed talker.”)

Mother, what’s editing?

Making writing better, checking information, correcting grammar, and being fair to the text.

Fair?

Mother believed she perfectly fit in the great line of judges who never made it to the bench. When she explained critical issues—This is critical, she’d say—like about editing, cleaning up my room, and the man I should be when I grew up, she gazed at me meaningfully; the knowledge imparted was the MOST important thing in the world. Her expectant look bewildered and dazzled me. What if I didn’t get it then—would I ever? Would I succeed in life? Mother worked herself up deciding how often to repeat the same info, and whether repeating it would be counterproductive or what.

Mater of grammar, fact finder, and syntax investigator labored in abstractions; before I was born she’d been an editor at a press in Boston; then with two little boys, she decided to freelance, edit books at home, in her sacred office.

We children weren’t allowed to enter if the door was shut, except for emergencies. I grew up believing in the urgency of matters behind that door, out of sight, and when I grew up, I could also shut a door and keep everyone and everything OUT. I could cut you all OUT. Father’s leaving for his law office had less value, because he left, and it was the house, the home, that mattered, Mother’s territory and mine: it had all my things, and hers. That’s an idiomatic comfort phrase: my things. I don’t use it much now, too babyish, greedy, and self-exposing.

Sometimes Mother drove to Boston to discuss work with a publisher, or get out of the house and away from us, I knew that, then later she toted not-yet-talking Little Sister to another professional, and another—neurologist or psychologist or psychic.

Some think I became a cultural anthropologist because of them.

Spiritualists litter (kitty litter, kidding) Mother’s ancestral line, with which, she maintained, she felt mystically connected. More, later.

face values

Family photographs were the subject of my dissertation and first book, You’re a Picture, You’re Not a Picture. I analyzed how families picture themselves through their own photographs, what that picturing implies in terms of association, sibling order, gender relations, etc. How does the sociology of the American family—for instance, birth order—affect pictures, and does that “fact” become an image for the family?

Narratives grow with and in time, the family story about what and who came when. If Little Sister had been the oldest, would she have spoken more? Father was the baby in his family, did him no good. The qualities that make the baby appealing just made him arrogant. Mother, though younger than Clarissa, couldn’t be the baby. Clarissa needed so much care, hot-wired the way she was.

Whose “I”/“eye” can be trusted? From what I learned in my family, I don’t trust anyone in front of or behind a camera, but I keep my bias out of it. Kidding.

Is trust an issue in art, and if so why?

I interviewed over a hundred families across America, and chose pictures from their stacks, or they did the choosing. They told me who was who, and what; what was going on, and weird narratives spilled out. I inferred meanings, as an ethnographer, sorting through the consonances and dissonances, and what the gaps meant, if anything. A picture can actually tell you very little, which is why Thematic Apperception Tests (TAT) invented by psychologists in the 1930s still appeal, at least in research. The open-endedness of pictures has been utilized to study the mystery of perception, emerging from an individual human psyche, as the subject sees into a picture what is not there. One can’t read an expression as a revelation of character or personality; it is just temporal, an affect, often for the camera.

Behind so many smiles, I see: Eat Shit, Asshole. But then that’s me.

The concept of family resemblance is reasonable, given genetics, but it’s peculiar, because what makes a resemblance isn’t clear, there’s no feature-by-feature similarity. Most of us in families share a resemblance. Fascination with the “family other”—a neologism I coined in an early pubbed article—is dulled by the other’s being related by blood; yet what’s near can be farther (what’s in the mirror is farther than you think), because up close, we’re less able to see each other. I don’t look like my brother, but everyone says I do. I feared Bro Hart. He wanted to kill me at birth. Reaction formation, correct.

Often we hate our siblings, our blood, who might be our murderers. The Greeks, Shakespeare, et al.

A family’s secrets appear as absences and exclusions, erasures and deletions. A first marriage was annulled: no photos. A child given up for adoption, no pix of the pregnant mother. The not-there, un-pictured life—think about it, an un-pictured life—or invisible story, hangs around the edges of albums, obscene, out of sight, off screen, you name it. Still, it functions along with the already-silent conversation of non-speaking pictures.

The incapacity to see—SEE—resides within the self, a condition I half-jokingly call The Fault Dear Brutus syndrome.

I’m sampling Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Cassius saying: “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, / But in ourselves, that we are underlings.”

Don’t tell Americans they’re underlings.

domestic visuals

Where are all the amateurs who do it for love, where have they gone?

In baseball stadiums, couples know, when the camera spots them, they should kiss, and they do. For love. For love of the camera.

I lusted after these so-called unposed moments, ephemera, even a lunch box called “The Remains of the Day,” in the movie Waiting for Guffman. Kidding.

My unguarded moments are not cool.

In found family albums and pictures lent to me, picked up or bought at sites for collectibles and common relics, I studied/saw a quality I want to call straightforward, pictures uncomplicated by ideas about art or self-presentation, some bearing the self-consciousness of their subjects.

When I looked at art photography, posed and unposed, I was drawn to artists who shot families and their familiars, like Carrie Mae Weems, Catherine Opie, Mary Kelly, especially her Post-Partum Document, and Mitch Epstein, his book about his father, which aligned with my childhood obsession. Later on, that entered into my dissertation on family photo albums and amateur pictures creating the family image of itself, and for society.

Artist vernaculars impressed me: Warhol’s photo-machine pix and Polaroids, Stephen Shore’s visual travel diary, Susan Hiller’s Rough Seas postcard collection, and Gerhard Richter’s massive Atlas project, in which he attempted to include every kind of image, or the impossibility of the totality.

When artists incorporate or appropriate unsophisticated or naïve work in their work, a double consciousness plays that game. Or, to say it another way, the artists are presenting visual meta-fictions.

Four “amateurs” represent how people pictured themselves—these date from the 1930s through the 1950s—

displaying attitudes through their stances, for one, and

approaches to being photographed. Two of them feature

people and their pets; one, a woman is in front of her house; and the other “stray image,” two men, one in a U.S. army uniform, the other civilian dress.

The soldier has his arm about the second man’s shoulders. Both men stand stiffly, neither smiles for the camera. They perform a “reluctance to be photographed.” Palpable discomfort especially rests in the body of the civilian; the soldier’s inclination—his capped head inclines toward the civilian—establishes familiarity: these men are “close” or know each other. Grimness, pictured—and resolve. The photographer stands at a medium distance, and has centered the men in the frame, the sloping roof of a brick building aligned with the civilian’s forehead. It is a stark image. Is he going to war? Is the glumness of the civilian significant? Or, is it only that he can’t stand being shot? I can’t know, it’s a mystery no one now can solve.

Their seriousness before the camera arrests me most. The two men, soldier and civilian, mean this picture to count, to represent their earnestness.

Contemporary men don’t pose that way. For one, the ubiquity of images has made picturing selves less significant. With the speed of the digital, a casual attitude arrived: this wasn’t going to be the only picture, loads would come, and many to delete. Our fast images: tossed away, worthless. Also, contemporaries maturing in an intensely pictured world experience the camera like a pet.

A woman in her forties or fifties stands in front of her house, presumably hers, unless she’s a servant, which doesn’t seem the case, because of the modesty of the house (though it could be servants’ quarters): she’s wearing a full, white apron. She has long arms, they dangle or hang next to her body, and settle at mid-thigh. The apron covers most of her short-sleeved, summery print dress. Her shoes date the photograph, probably the late 1930s or 1940s. (Mother will know.) Her hair is parted in the center, flat to her head, no frills whatever about her person; she wears wire-framed glasses, which go in and out of style. I’d call her a plain woman, and this a plain picture. She appears serious, at least about having her picture taken, but her body looks relaxed. Still, there’s nothing casual about her or this picture. It was posed. That she would take a picture with her apron on says something about class, her “plainness,” determination, sense of herself. No fussing for picture-taking. She’s the picture of neatness.

An image: “picture of neatness.”

In a color photo, a woman is seated beside her dog, both on kitchen chairs. A homely scene, the woman wears a half-apron (in the age of aprons), and, behind the two figures, appliances including a coffee pot and washing machine. The dog is holding up one paw, while one of the woman’s hands is raised above the other (that one lies in her lap). To the left of the frame, a part of another figure, an arm, apparently a man’s, in a long-sleeved plaid shirt. What is striking: the parallel pose of woman and dog, their equal status in the frame.

In another, dated on its back “1948,” a kneeling boy of twelve or so and a white kitten sitting on a wooden dinner table chair. My first take: it could be an artist’s. Why? Notice the frame within the frame. The boy stares out, not without expression but one that isn’t legible; his face is poised between the chair’s back slats. The white kitten, foregrounded, sits remarkably still and calm, while the boy looks at it with fascination or curiosity. Behind the boy, a telephone pole, a house with a porch, all indicate a neighborhood. The chair dominates, its top cuts the plane in half. This accidental framing, I imagine it was an accident, makes it a picture, not a snapshot or family photo, but something more. The composition is disorienting, unexpected, with several special elements that call to the viewer’s eye.

“Naïve” or amateur shots can be differentiated from current artists’ renderings of supposed unposed moments because of framing, sure, but also by attitudes toward what’s permissible in a picture, what a picture should be, and how people should act for or look in one, present themselves for the record.

Pictures become a memory for which you have no actual memory. Pictures augment memory’s elusiveness, how much more is forgotten than we think. A pictured moment has resonance to me, not as a fact of life but as an impression from a time in which THIS behavior happened, etc. Some artists don’t title works—Barbara Kruger doesn’t. Her work uses text and image (text as image), and, for one thing, the text acts like an internal title. Other artists might number a piece or title it to direct interpretation or a way of looking. A caption or subtitle shapes a picture, but a picture wants to resist finitude.

domestic visuals too

I was totally conscious, as a little kid, of life passing, and when I saw a brilliant fall leaf hanging from a tree about to drop, seeing it from a car window, I thought, I’ll never see that leaf again, and felt sad, and I don’t know why, at four years old, I felt such loss.

The French, right, have a smart phrase: nostalgie de la boue.

In our family’s albums, “leaves” were glued on pages (leafs) or set under plastic, and maybe I experienced something like D. W. Winnicott’s “holding,” far from consciousness. The ephemeral was transformed into a document that turned into a monument to memory and “truth.” There it was, Mother as a girl.

Samuel Beckett: “All art is the same—an attempt to fill an empty space.”

I’d lost nothing, nothing I was aware of, only what everyone loses when the amniotic sac bursts, and you, fetus, drop, get pushed through a tight vaginal canal, and thrust into unexpected environs.

We didn’t know.

Now, always, trying to fill the emptiness.

I spent, spend, hours, weeks, months, from my young life on, with pictures, absorbed by their mysteriousness, there yet not there. WHAT IS THERE?

ethnographic values

Ethnography focuses on actual people. “Real” people in “real” situations. That’s how I articulated it to myself. I wouldn’t just be rocking in my own head, limited, but my mind could spread out. Ha.

No escape from patterns and systems, no exits. Nothing, and no one, resides outside a system; that’s the way it is. Nothing outside the inside, the inside is also outside, etc.

The Unabomber, a solitary man hiding in a house in the wilderness, mailed explosives through the U.S. Postal Service. His wish for recognition or “success” led him to publish a manifesto in The New York Times. Theodore Kaczynski, a so-called lone wolf, had typical human needs, and they doomed him. His sister-in-law recognized his writing, his philosophy, and reported him. If he hadn’t demanded publication, threatening to kill more people if the Times didn’t publish it, he might never have been caught and jailed.

Maybe he wanted to stop his murdering, maybe not.

Deluded, but horribly effective for a while.

In 2007, Sicilian police reported finding Sicilian Mafia boss Salvatore Lo Piccolo’s list of Ten Commandments for how to be a good gangster.

No one can present himself directly to another of our friends. There must be a third person to do it.

Never look at the wives of friends.

Never be seen with cops.

Never go to pubs and clubs, etc.

My fave commandment: The people who can’t be part of Cosa Nostra are those who have a close relative in the police. Also, anyone who behaves badly and doesn’t hold moral values.

People delude themselves; but delusions are based in a general culture, and dissension responds to and appears in recognizable forms. Totally disturbing. Sometimes I believe that, with will and effort, I can overcome and think for myself. But what is that, who is it thinking? I think in a common language. Writers will infrequently find unique articulations.

I don’t mean I want to metamorphose into a wild child, which might be cool, but discover what I think, if capable of purging my mind of certain images that determined, even predetermined me.

A THOUGHT is an effect of a specific education and its environment.

For cohesion, people need to play ball in the same conceptual park, and make systems for survival, structures like eating three meals a day. People follow that here. Some skip a meal. No biggie, really, skipping a meal still recognizes the system.

Individuality is a necessary fiction. But why? Why do people seek to know their own minds, when knowing won’t change them; people think they’re right, right? Outcomes and events are often coincidences, unplanned, and may be appealing or unappealing, but humans imagine they can plan—plot—their lives more than they can. Some schedule their hours as if running an army, this must be done now or then; if a friend changes an appointment on one of these characters, their foundation crumbles. They become enraged at the “un-settler.” (My term.)

People desire the un-plannable: money and success, happiness, love, health. A person’s “fate” is traduced by consequences that are not predictable.

Accidents of fate, and happenstance, make us who we are. Take Oedipus: he knew but could not accept his fate, which crushed his sense of individuality, of opportunity. He couldn’t make his own way. Greek hubris depended upon people imagining freedom from fate, or consequences, from what could be called social and cultural mandates.

family tales

There’s a story in my family about Great Uncle Ezekiel, who didn’t know, until he was eighteen and married to Margaret, that women went to the bathroom. It’s always told with that euphemism. Uncle Ezekiel belonged to my father’s side of the family. My father told it to my older brother, Hart, when he was thirteen, then me at thirteen—a father-son rite of passage deal—and his two brothers told their sons, then their daughters, when everyone loosened up about girls.

My parents told loads of stories about their upbringing—up ’til the point when they couldn’t make sense of them, or why they were telling us, which reminded them: They shouldn’t have had children. Three of us shouldn’t have been born. “But we had YOU. We love you.” Sensible people/parents: they waited until the best time, they said, to have the best children. All that pimping their gene-carriers’ supposed exceptionalism, and they bestowed upon us “unique monikers.” I’m Ezekiel (Father’s great uncle, also a sixth-century prophet); Hooper (maternal surname, related by marriage to the Adams family); Stark (paternal German-Jewish-English-Unitarian, or neutralists). In grade school, my name rhymed with everything dumb. Brother Hart Adams Stark glories in his, imagines he’s special, like Hart Crane, the writer. Bro Hart is just a pathologist who suffers from what psychiatrists call taphephobia: he’s totally afraid of being buried alive. No one knows why.

Little Sister doesn’t dwell on her signifying handle: Matilda (Tilda) Hooper Stark. Not publicly. (Matilda was the name of a great great great Hooper aunt.) She doesn’t mention a lot, because she suffers from selective mutism, so she can talk with us, family, close friends, otherwise she’s mostly silent. She couldn’t speak at school and with strangers—now she says mostly she doesn’t choose to. She talked when she was moved to talk, like a Quaker. When we were kids, I believed she chose not to talk.

Her shrink believes she suffers from alexithymia—

trouble experiencing, expressing, describing emotional responses. Which may be one reason she speaks selectively, or the reverse. A while ago, I read about it in the Times. “People who are confused about the sources of their own emotions . . . tend to report little benefit from a burst of tears, studies have found.”

When Little Sister cries, it doesn’t sound human, more like she’s choking.

She’s six years younger. Ten years younger than Hart. That’s the spread. I understand her better now, identify more, though identification can also be mis-identification. In some way I always felt close to her, though she blames me for talking too much when we were kids, and not giving her a chance, which is probably true.

Little Sister is another twist or tangle in the family wiring.

I’m the middle child, so I blame top and bottom, squeezed and dislodged by both. I can play that card.

Yeah, I’m cool.

Ethnography isn’t a nineteenth-century discipline anymore. There’s rigor, or solemnity, about approach and methodology, sure, but there’s a restive criticality in our fractious field about subject/object relationships; objectivity itself, challenged especially by postwar theories, e.g., post-structuralism; and, straight up, the field’s been upended, blasted, or maybe for some lies in ruins. Optimistically, it’s been helped by its contradictions and differences, and these might lead to more Ph.D.s, which is cool, because it keeps everything moving (primarily for jobs).

My focus on images in, by, and of the family includes sexual and gendered behavior and relationships as understood in those pictures. I’m thirty-eight, an assistant professor in an Eastern university. I’ll get associate, tenure, if I don’t piss off the department stiffs by being “too clever.” Have to walk the walk, then like everyone else who’s tenured do the big fade.

Cultural Studies scored during the 1990s; since then, the academy’s star is like life in Warhol’s Factory, who’s up, who’s down, a guessing game. There’s been lots of theoretical work on masculinity, which probably got me thinking about men my age. Many moved into it, and some have shifted to transgender studies—Humanities, that department is disappearing, a sideline to the main game, Tech, Science, Abject and Obesity Studies. Sort of kidding. Let’s say, the older fields are in as much flux as what they study, transitional objects and subjects. But strangely we proceed, no Sundays off in the post-1960s academic and not-so-academic civil wars.

A cultural anthropologist reflects on differences, similarities, patterns, problems, gathers information, takes notes, keeps a journal—makes field notes—is an observer and a writer; we look at how human beings act and collaborate or not. We try to make sense of “why.” We study others and increasingly ourselves, and what customs and behaviors do for the society that enacts or supports them.

According to Geertz, ethnographies are also interpretations: “We begin with our own interpretations of what our informants are up to, or think they are up to, and then systematize those.”

Ethnographers study commonalities among cultures, societies, the essentials, the basics: people need to eat, find shelter, procreate, etc. The differences in values, rituals, kinship relations are works of creation, born from, in part, basic needs and social conditions, etc., but adaptations and specifics range widely. A multimillion-ring circus, in Venn diagrams, unreadably dense, subsets and sub-subsets crisscrossing, is seemingly infinite. An ethnographer, again following Geertz, makes an intellectual effort toward thick interpretation (see later). I interpret

with as much complexity as I can bring to the worlds I observe.

Culture is only the pattern of meanings embedded in symbols, thus spake Geertz. Primitive doesn’t mean “primitive”; “we,” “they,” all pronouns have begun to act the way pronouns are intended: they shift. They, them, us, we, you can be anybody—we can all be subjects and objects of investigation, and are. Everything and everyone’s being studied, from Tokyo post–3/11/2011, senior centers, the Sydney beach scene, London clubs, Borneo mating habits, Brazil’s plastic surgery industry, Samoan society since WWII, NYC’s gangs, etc. Etcetera. Almost anything goes under the knife.

I view society through images, in words and pix, in how individuals see themselves, in past and present tenses, and with what they identify, which are also images. That’s my gig.

I started out in the field, I mean, got name recognition, presenting a paper at a conference: “We are The Picture People.” I began: “I name us Picture People because most special and obvious about the species is, our kind lives on and for pictures, lives as and for images, our species takes pictures, makes pix, thinks in pix. It exists if it’s a picture and can be pictured. Surface is depth, when nothing is superficial.”

Brought down a shaky house.

looking fills time

Pictures demand mental space and time.

In photographs, unguarded moments lend themselves to interpretation, and also to obliquity. An unwitting gesture doesn’t reveal the person. Maybe there’s more paradox to unposed moments, though; I hope to make something of those. But to pin down ambiguity, how weird is that. Ethnographers toil there, our milieu, especially those of us dedicated to thick description, where meaning exists in situ.

It’s ineluctable. A picture describes, say, but never defines. An accidental pose can tell more, we often suppose, than a studied one; Freud made a lot of the unconscious of the accident, especially a word slip. But subjects in a candid shot, accidents—not the same. Think about “truth” or revelation in Warhol’s Screen Tests, his silent or oxymoronic still movies: he focused on a person for a three-minute 16mm roll, and dared the poser to drop the pose (like a fetus through the birth canal). He didn’t make posing easy, he wasn’t looking for poise. His subject must breathe, creating movement, though each sitter was challenged to perform stillness. Weird, as if each sitter might be an Empire State Building. A psychological experiment, sure. Doing this kind of film, Warhol invoked early photography that required posers to sit still for a long time. Neck guards were invented to hold the poser’s head straight, immobile. Warhol’s poser had no guards other than his or her guardedness.

OK, the pose drops, but no essential truth is revealed. Unless one thinks that beneath the pose or the surface lies a greater truth. We’ve been led not to trust people’s appearances, because, it’s suggested, an essential truth about people can’t be seen at all or easily on the surface. A lie is different from an appearance. Conscious liars know they are lying. But everyone has an appearance, which can’t lie, even as appearances change and are chosen. They are not lies. A surface is not a lie.

About a photograph: its surface is its depth; there can be no single, correct interpretation; its depth rests on the surface, and, when you recognize that it can’t be read absolutely, it opens up as its own thing. Not revealing anything but itself. Another paradox.

G. E. Moore’s famous paradox: What can’t be said in the present tense—“It is raining, but I believe it is not raining”—

can be said in the past tense—“It was raining, but I didn’t believe it was raining.” A photograph indexes the past, and is viewed in the present. This means it can be raining in the picture, and not raining when a viewer sees it. A photograph is a fact, an object; but the picture is an experience, not a fact, for a viewer.

I’m no realist, but I live inside a reality, a world that isn’t completely mine or consistent, and I share aspects of it with other people. I can delude myself, and also, I like some illusions, they soften hard edges, soft-focus my days. Without illusion, life would be stripped of fantasy’s plenitude.

Plus, I wouldn’t look at art if it held a mirror to life, especially my life. Kidding. Not.

living in a glut of images is not

the same as being a glutton

A 1990s TV camera ad: “Life doesn’t stop for you to take a photograph.”

One hundred years earlier, “Nabi” painter Pierre Bonnard photographed his lover/partner Marthe, family, and friends—including friend and Nabi painter Édouard Vuillard—in gardens and forests, at play, eating. His photographs of Marthe in her bathtub became studies for his paintings. (I heard that Marthe suffered from psoriasis; took baths for relief, so it has affected how I look at them.) Bonnard liked his figures in movement, to catch the moment as few photographers did then (though Muybridge would, famously). He used his still camera like a cell phone, and by the 1890s when he started photographing, always as an amateur, the shutter speed was there: In 1880, George Eastman had developed a camera whose pose time was 1/50th of a second. Life didn’t have to stop.

An arm, leg, a glimpse of torso, Bonnard’s framing is unique. People danced across lawns, out of frame, they flew in the frame, two men wrestled in the air. Energy suffuses his pictures, or the dynamic called Life.

One always talks about surrendering to nature. There is also such a thing as surrendering to the picture. —Pierre Bonnard, February 8, 1939

My favorite picture is of Renée, a little girl, hugging a dog. She is bending down, over the dog, her head and face enveloped by a floppy straw bonnet. Three shapes dominate, all centrally framed—a little figure in a white or light-colored and loose smock-like dress; a big straw hat whose brim overwhelms the head and face; and a large, black dog whose head is cradled in one of Renée’s arms, the dog’s nose and face to the camera. Renée is wearing dark socks or stockings; one of her feet is lifted slightly off the pebbled ground, in movement. Her tiny foot moves the entire picture off the ground and into space.

Bonnard’s photographs look as if his camera brushed the surface in fast, loose strokes. Some call them painterly. Bonnard courted flow, or energy, and this correlated to the way he saw in whichever form or genre he used. A broad and complex concept: how we see and what seeing is. It is a mystery, not biologically, but neurologically, culturally, and psychologically. The elements for sight—or vision—depend on culture and society, and remain mysterious because the outcomes are not the same for all people, even when produced within the same structures.

Selective seeing is like selective memory: memory’s impositions, derogations, and biases (in favor of the rememberer) situate the psychological, social eye, and confound simple readings of reality: compelling variances of what is seen compete as “Truth.” The eye organized by culture, say, compels “seeing.” (I look at a dog or a cat and never see food. Rain to me looks like a drizzle or a downpour; other societies have many more words for rain.) People project, mostly unaware of the mechanism, and so reality’s constructions conform to already received ideas about it. Contemporary photographers work with that prejudiced, psychological, subjective eye, to play catch with, say, actuality and fiction.

The desire to catch, as Bonnard hoped, the PASSING MOMENT is antithetical to being in the moment. The photographer is an observer to others’ moments.

The Picture People have dedicated themselves to this paradox, and consign themselves on either side of the equation.

family values what

I was a boy who didn’t kill insects or torture small creatures, except Little Sister. She claimed I tortured her, tormented is closer to the truth.

One summer morning I found ecstasy in the garden, our backyard. I was four, and a praying mantis appeared. I didn’t know what it was. The creature, I named him Mr. Petey, rocked my world. I watched its little head turning on its neck—the only insect on earth that turns its head. It’s a person, like me, I saw, but even littler. Praying mantises are like dinosaur-age humans. They have a face. They look you in the eyes. Their eyes are in the middle of their tiny heads, and they see the way we do. Totally cool. My PM noticed me and looked right back at me. At me, and I was face-to-face with a god or an alien. The PM got me, he communicated with sympathy and intelligence.

I named him Mr. Petey and wanted him for a pet, a friend. (My parents wouldn’t let me bring him indoors.) I could talk to him—he could have been female—he listened to me, and pretty much every day I went into the backyard to find him. Mr. Petey usually showed up.

You can’t kill a praying mantis, Mother said, they’re a protected species, and if you kill one, we’ll have to pay the government a lot of money.

I wasn’t ever going to kill Mr. Petey, she was crazy, but I heard about the existence of a protected species, and this thrilled my kid-brain. I wondered if I was one, a special boy with special powers because I knew Mr. Petey. I reveled in talking with Mr. Petey, when I found him on a leaf.

That took some effort. Camouflage is key to a PM’s survival, they have many enemies, including birds. (Sad, birds are cool.) Mr. Petey might fear predators but he was a fearsome predator, invisible on a branch.

You can’t find a PM stuffed animal, so I made drawings, and Mother sewed me one. Mr. Petey’s head flops down after all these years, nearly decapitated.

Mr. Petey—seen it all—Mr. Petey plural. I didn’t know then that he/she lives only a year. Still, a PM’s short life span fundamentally defies the value of human longevity, its evolutionary merit. The flaws of living long but not living large. Not kidding.

I must’ve fooled myself—kids don’t fool themselves—when a new PM showed up, because their markings and colors vary. I don’t know what I actually thought, it’s all retro now. But a PM showed up in the spring and stayed through summer, I called him/her Mr. Petey, and one day he went for a vacation in the South. I figured that out for myself. But that was always Mr. Petey in the backyard until I left home.

I was a dreamy kid, I’m a dreamy older dude, but in a totally different way.

My dreaminess gets called “an obstacle to reality.”

Looking, observing, I’m never bored. People who get bored are boring, people who don’t get bored may not be boring but could be arrogant assholes. I’m not a voyeur, not clinically, according to the tests, but in a way, everyone who’s awake is looking somewhat voyeuristically, or voyeur-ing. And, also, what can tests measure except a society’s preconceived values, already tainted by its goals. If I am, I’m a pretty passive voyeur.

Landscapes flying by train windows make me sick.

Soberly, I examined objects, close and distant, a star in the sky, Mr. Petey, Mother’s face; but I noticed: the elements that seem close may really be distant, your father, your best friend, and what feels distant or remote may be closer than you expect, and sneak up and rock your world. It’s facile to say: the terrorist living next door, the serial killer—such a nice guy.

art, images, death

Commercial photography sped up with the advent of the U.S. Civil War: the tech was there, and people could have pictures of the men who left for war, often to die or be maimed. Before, there weren’t remedial visuals or visual transitional objects to survive them. (See D. W. Winnicott.) Hair, nails, other physical remnants and traces were collected and framed, glued in lockets. Fingernail pieces. (Disgusting, sorry.) A rare few had painted portraits on mantelpieces.

First cousins married until after the Civil War, when the Feds made it illegal. In the age of Darwin, Americans worried about their purity, and the government worried about social degeneracy, the birth of idiots. First cousins not marrying doesn’t stop that, but may amplify occurrences.

People relied on memory, and also developed mnemonic devices, ever since the Greeks and Romans. The “method of loci” (places) routes memory through visualizations (images), situates a person in a place who then records the site in the mind/brain. Later, the person walks through it mentally, sees everything, and what needs to be remembered appears.

Contemporary artists don’t “reflect” objects; artists are IN life, making not “imitating” it, and they also can see objects not as separate from their own lives. Artist Laurie Simmons, in her series The Love Doll, photographed a Japanese sex doll, or surrogate female, in domestic scenes, where the Love Doll sits on the living room couch, for instance. Simmons’s work pictures social attitudes, sexual fantasies, the regulated poses of femininity. “Attitudinals,” I call them.

Artist Rachel Harrison: “People see what they want to see. My art is always loaded. There is too much, on purpose, because I’m not going to give you the thing you want.”

What is that “thing”?

A claim was once made: artists make art from chaos. People who say this know nothing about art or chaos.

(1) Chaotic people make chaos, and can’t unmake it.

(2) Chaos is not an object.

You’re alive, dead. Can people be that different now from when bodies lay dead in front rooms? Consciousness: is it the same process always, and only its contents changed?

Virginia Woolf: “The look of things has a great power over me.”

I get comfort from artists’ representations of mortality—entrails of the day, autopsies of consumer goods, chunks, slices or mind sets, present-tense approaches.

Where did all the “history paintings” go? Depends on what you think they are. Barbara Kruger’s images, words, vertiginous, on walls and floors, remaking space and received ideas. Cindy Sherman’s buried phantasms of degradation and decadence; Peter Hujar’s black-and-white photographs of catacombs; Renée Green’s Partially Buried, an unearthing of a Robert Smithson piece and the Kent State killings; Zoe Leonard’s ten-year Analogue piece, photographs of NYC shop windows, signs, a project of capture; Stephen Prina’s reconfiguration of art exhibitions, or the past as an installation; Judith Barry’s Cairo Stories, film portraits based on interviews with Egyptian women, their histories entwined with their country’s; Walid Raad’s preservation through images of Lebanon’s civil wars; Glenn Ligon’s “A Feast of Scraps,” in part vernacular photographs of African Americans, an image-history of black America; Jim Hodges’s A Diary of Flowers, a history of sentiment; An-My Lê’s photographs of Vietnam War reenactments staged in North Carolina.

How is the past installed, whose and which history, for public view.

Ilya Kabakov’s room-sized installations, Soviet Union dioramas, and fictional picture books of invented characters; Moyra Davey’s photograph of dust on a phonograph needle, history as residue; Song Dong’s color-coded installation Waste Not, 10,000 objects from his hoarder mother’s Beijing apartment, nothing could be thrown away; Silvia Kolbowski’s “An Inadequate History of Conceptual Art,” including photographs of artists’ hands, as they talked about an art form that avoided the hand; Adam Pendleton’s black-and-white photographs, collages of protest, text, and pictures; Christopher Williams’s pictures that question what photography (pro)poses; and Barbara Probst’s point-of-view photographs that include her camera, the eye’s prothesis, and tripod. The apparatus on show, though no transparency through transparency.

blame empiricism

Toward the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries, there had been rumors of photography, in the days when science and art were near-inseparable, spreading among the elite—educated men and a few women, scientists of all stripes, creatures of the Enlightenment. They heard about the progress of various scientific trials, experiments toward image fixing that had begun in the late eighteenth century: camera obscuras, and attempts to plant ephemeral images on a surface through the effects of light and chemicals.

Photography emerged out of positivism, photo historian Geoffrey Batchen has theorized; photography is like a symptom of positivism, an obsession about proof, for documenting existence. It trusts empirical evidence, it is empirical evidence. Photography’s origins can slide into an incessant hope for proof—of anything. It becomes a force in itself, as making images makes us.

Our species needed to fix an image of a house or bridge onto a plate. It did this before finding a way to eliminate the excruciating pain of surgery, say, tooth-pulling. The drive for anesthesia was not higher on the scale of need or wish: to impress a bridge on a plate or piece of paper, that happened first. OK, anesthesia emerged pretty soon after photography, in 1846, when a dentist demonstrated his experiment to physicians who’d sort of given up. Why give up? BECAUSE people believed our species’ fate was to suffer, to experience pain, like women in childbirth.

We are all Job; but my biblical namesake Ezekiel was all about curing with herbs, etc.

Attitudes affect revelations, what gets invented, and doesn’t, the way society has evolved and continues.

What’s important to humans is less important than why.

Empiricism fails, what we see isn’t what we get. Love can’t be proved. No science to it, no proof in repetitions of it. Certain acts seem, indubitably, love: a mother throwing herself on her child to save its life. Love, instinct, or something else. Fear of future guilt or ostracism from the tribe? Instincts that appear altruistic may not be: the mother’s done her reproductive work. Let’s move on.

anon family album throwaway pix

I hold these pictures in my hands—faces and bodies, dogs and cats flip from one to the other. Pictures, pictures.

Families are tribes, tribes keep relics, pass them on, relics represent ancestral traditions and “purpose the future” (my term). Our relics, these valued objects, “hold” a family, tribe, a people’s continuity. “High art”—relics of a kind—creates continuity in value and taste, which is essentially what museums do: hold values continuous. While most of us know, well, some of us, that life is whimsical, temporary, in flux, random and discontinuous, museums, churches, “culture’s placeholders,” my term, forge constancy, and though criticized for their many lacks, these institutionalize traditions, give tribes places to go to venerate the past and present, together. How else would people know on what to base their values? Why is the archive so important? Think about it. The twentieth century is GONE, so gone, as never to have happened. Buh-bye.

Or the Velvet Underground’s “bye-bye.”

Societies, without histories, have no value. People without history, also. Values thrive in relation to the excluded, to the much greater number of objects called obsolete, or unnecessary, ugly, second-rate, third-rate. How else would people, societies, know themselves?

In my hands, I hold these picture-relics, to be family-evident.

In Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance, Geof-frey Batchen studied a picture At Rest (dated 1890, he thinks) of a dead young woman, wax flowers around its frame. The flowers add poignancy and sentimentality. He asks: “Who was this woman? What was her life like? What possible relationship could I, as a viewer of this picture today, have to do with her?”

I ask myself that every day.

loving a praying mantis: on the road

to ethnography

I was a morbid kid, but also kind of happy, nothing stood in my way, except Bro Hart and Father. Kidding, not.

I saw us through Mr. Petey’s eyes. We/they were fools in clumsy shoes, ugly aprons, eating burned hot dogs, complaining about bugs, while getting loaded and uploading shit on others, people were just stupid. Mr. Petey watched, hunkered down on a leaf, invisible to dull adult eyes.

PMs are carnivorous, so the smell of burgers wasn’t disgusting to him. They eat their prey alive, but paralyze them first.

PMs’ ability to turn their heads 180 degrees allows them great visibility, also their eyes are sensitive to the slightest movement up to sixty feet away (two-thirds to first base). They have powerful jaws for devouring their prey and ultrasound ears on their meta-thoraxes. They are so aware of their environment, built that way, like some humans who are called overly sensitive.

PMs blend into a plant’s leaves and only their movement gives them away, so they fool other insects and us. They can’t be fooled because their brains aren’t stymied by the problems ours handle, which are bigger than our big brains can actually manage. If a brain is small, dedicated to fewer problems, and those get handled exquisitely, that organism isn’t less smart than a human.

His species required no improvement, think about it: he didn’t need to evolve, like our imperfect species—heavy skulls sit on top of spindly, multi-parted spines, the body’s primary support structure.

Women have narrow pelvises, to winnow out fatheads.

Shoulders are needed for too many functions, too many directions in which they must turn. The knee, by comparison, is more simple, the hip a simpleton.

Mr. Petey was small, efficiently built, and effective.

He cogitated, my thinker-insect. Thought = action.

Go ahead, go play on your own, Mother used to say. I loved that.

So what if I didn’t have a “good personality.” Mother claimed my personality showed at birth, but my character emerged later. Go figure. My family has strong opinions—principled, stubborn, righteous, judgmental; they’re reasonable, smart, assholes, bigots, or nut jobs, depending upon your POV and linguistic code. My father told me I was a brat; Mother might call me sly or rambunctious. Maybe I wasn’t cool enough or too cool for school, and so what if Hart beat me up or sat on me and tried to suffocate me or tickle me to death, or Little Sister sometimes ignored me; so what if I wet my bed until I was five or sucked my big toe, not even my thumb like normal kids, or had three cavities at age four because Mother feared government control by fluoride. She was otherwise a pretty rational person.

native, naïve not

The so-called native informant—a native can be anyone, a member of the Zuni tribe, or an upstate New York gang member, or a DJ—is not an innocent informant. No one’s innocent. How should an anthropologist behave with informants? “It entails trust between the ethnographer and subject” (more later). The ethnographer can’t trust that he or she knows their subjects’ motivations for cooperation. The ethnographer can’t entirely know his or her own motives for talking with or choosing subjects. The most obvious stuff wasn’t sixty or seventy years ago, and new-style obvious-ness hides in blatant plain sight. Many humanists and social scientists are totally incensed, everyone appears to be incensed about the loss of objectivity and Truth with a cap T. It’s not the end of Western Civ. Or it is. Does it matter?

I started with “naïve” images, or I was naïve, the images weren’t.

I remember thinking, what’s happening inside everyone. I wanted the illusion—a picture talks to me.

I haven’t entirely progressed from the vernacular, in all ways. Haha.

See, the naïf or amateur has no cred in our digitized world. There are no amateurs. Does it mean there is no love in what people do? No, it can mean that those who do it professionally are not as valued, or even themselves value it less, oddly. Or, that everyone feels able to take good photos, and they are—good enough. Yet what is a good photo, and by whose definition?

Some people get paid to take pictures: the professional class, experts, artists, specialists. Often they talk only to each other, a small circle of other picture people. The majority take spontaneous, unplanned pix, especially of family and friends, in which there are what I call “display stances,” image-ready attitudes, position-motifs showing status, etc. In the picture-taking and -making age, each generation matures with technologies that “show” them to themselves and others, so everyone can assert self as an image; we are all in image-apprenticeship, and it is through pictures we see ourselves and learn to shape ourselves, to present ourselves.

The pictures don’t need to be reflexive. Portraits of selves reside inside or beside portraits of desirable or desired others, too. The other’s desired life is a fashion or style, there is no inner to the outer-wear. Fashion and style rule because the shopper assumes the style of the designer and imagines it’s his or her own. When in fact he or she is merely branded. (See Erving Goffman’s The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.)

Pictures don’t tell stories; they match—align with—stories we tell ourselves. In the early 1980s, artists Louise Lawler and Sherrie Levine posted this on a movie theater’s marquee: “A picture is not worth a 1,000 words.” It isn’t, but if it doesn’t tell a story, what, if anything, does it tell? Do our lives lean heavily on nothing?

HBO’s Six Feet Under (2001–2005), a droll series, showed Claire, one of its protagonists, in art school studying photography. In its finale, before leaving her house and home for the unknown, Claire shoots it and her family. Suddenly, Claire’s dead brother, Nate, a ghost, looks on, and whispers to her, “That’s already gone.”

But Claire takes the pictures, because she’s alive, and present to remember.

tellings

Uncle Lionel liked to recite this ditty:

Yesterday upon the stair

I saw a man who wasn’t there

He wasn’t there again today.

Oh, how I wish he’d go away.

I wished upon the first star that winked at me in a black sky: preserve me, keep me safe, oh little angels in heaven. (No religion practiced at home; angels appeared in museum paintings.) During the Reformation, I might have volunteered to be a castrato and resisted maturation. I heard a recording of the last-known castrato, made in 1904—an eerie boy voice.

I wonder if his face stayed boyish. I wanted to stay a boy. “I’m not going to grow up like you, I won’t become an adult.” Typical for Americans.

My secret world, once upon a child, included my photo library, definitely a formative, building-block experience, with a system only I knew, because I conceived of it. I hid it. I stored and preserved (thought I did) what I wanted. At age nine, I classified pix, and really did my best to preserve them. Martin Scorsese says preservation is film-making. Think about how much of existence goes into preserving what could instantly disappear, and maybe should, like taking a photo at a wedding. Good or bad? Which is important, the moment or the preservation?

I named my analogue catalogue Zekabet, coding by colors and numbers and symbols I liked—naturally, the praying mantis was significant. It was a kind of me and not-me formulation. My color was dark green, like Mr. Petey’s; any home video or Super 8 I appeared in was marked with a dark green Crayola; if I shot it, it was marked with lime green, and any green was number 1. Bro Hart was shit brown. Little Sister violet, Mother gray-blue, Father real red; these accorded with their temperaments. (Mother once wore a mood ring, made an impact.) The code never left my pocket. My biggest conceptual issue was how to show the passage of time, not by dates like the year, say, 1980. Too easily decoded. So, I created a calendar that related to weather, that is, when weather first was recorded in 1870, or Year 1. Simple, but cloud formations and movements were also factored in, because I was entranced by clouds and why they took the shapes they did, that they had volume but were made of air, of space. That killed me.

In the Zekabet, Mr. Petey ranked over all creatures; Little Sister was a special human-creature; also ranking high: outer space, robots, D&D, clouds, rocks, family photos. Kid-time felt eternal, off the charts, and what I felt then was limitless, or more prosaically, if there was time, it was like the waves I watched breaking far from shore, without end or thought, one after the other. No concern for anything.

An endangered species and I were friends.

Am I an endangered species?

Time stood still when I picked up a smooth gray-blue stone, flat, nothing exotic, but it was in the backyard.

A rock with a crevice, maybe it encased a fossil. Looking, I was outside of time, and as I said, never bored.

Perpetual stillness: still photographs do it for me, not movies, videos. Stopped time is an illusion, OK, is there life without illusion? Delusions, that’s different, I know from experience, though experience is a relentless, wicked trickster. Oh wickedness! Yet an ethnographer is encouraged to trust it. See, here’s the fault line, there’s trouble in paradise.

I was born in the USA, near Boston, MA, June 29, 1978, close to midnight, so I straddled night and day, the 30th, and those numbers mean a lot. To me. When I gamble, I go to them.

“You’re emotionally immature,” Mother says. Little Sister smiles, faintly, pissing me off.

I know I shouldn’t have children.

Parental laws included: “Act like a grown-up.” An act. “Why act this way?” I yelled. “’Coz, then it’s all fake.” A “time out” would get called, I’d skulk to my room, where I calmed down with pictures and games. Everything came to seem fake. I saw that, as you grow up, your true self withers away, though the State doesn’t, and you find yourself accepting rules, because that’s how it’s done until one day you decide: I don’t want to walk that walk.

Virtues of backyard = safe space.

I could be alone there.

I learned to embrace aloneness. Big plus for an eth-

nographer.

Our garden led to the big forest, the unknown, and any stone was a solid thing I could hold in my hand for as long as I wanted that didn’t ask me to do anything or be anything, it wasn’t for or against anything, it wasn’t bad, good, it demanded nothing, like a potential true friend should demand nothing. I learned that true friends were rare, that mostly everyone demands something you can’t give them.

When I started school (still being schooled by life, haha), my anxiety launched into outer space. First off, school wasn’t home, there were other kids, there was me; I had to be with them, but they could have been other kids, which Mother made a lot of. Was I with the best people, for me? Did I have the best teachers, for me? There was something about me that caused “parental concern,” a specific form of tribal concern. The word “gifted” popped up early on the school screen, and meant nothing to me except I was different or special, not the way I felt to myself but to others. Bro Hart wasn’t, and that was cool, I wanted to be different from him. Little Sister owned her difference, though it wasn’t a gift. To me it kind of was—I didn’t get that it was a problem, until later. I thought Little Sister liked her specialness, since it brought privileges. Hart wasn’t ever my parents’ problem, but the word “track” got thrown around. He was tracking right. I mean, what the hell. I didn’t know what was going on with Hart. Gifted kids don’t necessarily score high on tests or do equally well on all tasks and responses. My track got skewed. Or, I had a screw loose, depending on who dissed me.

The “gifted” brand rests in a Pandora’s box, a grab-bag of mysterious stuff. I heard: How should Zeke be “handled”? Is he overly sensitive? That shit. Ultimately I took the label and ran with it; I sensed I could do with it what I wanted—“let the boy have his head,” my namesake Great Uncle Zeke once burbled. I followed my investigations; plunged into what I declared “research,” and poked my nose into the family image fog. (Prefigured my becoming a cultural anthropologist.) In high school and mostly in college, I avoided family history, maybe with vehemence. Now, people think it’s the subtext, or true undercurrent, of my life.

First off: I hated school.

(1) Didn’t understand when learning started or stopped.

(2) Didn’t like other kids. Maybe one or two.

(3) Wary of girls, if they talked to me; if they didn’t, I fell in love.

(4) Was too aggressive OR not enough—for a boy.

(5) Could boys wear nail polish, like rock guys, and why not? (Possible origins for my work-in-progress MEN IN QUOTES.)

sacred photography

I’ve worked, formally, with family photographs since grad school. People open their doors, let you in, they answer questions about intimate parts of their lives. What’s at stake for them is part of my investigation. (For one thing, people want to think their lives are worth talking about. That they mean something. That’s totally upfront.)

Then: Why am I interested in this? What’s my stake in this?

All “portraits” are also self-portraits.

In the nineteenth century, Thomas Carlyle believed “all that a man does is physiognomical of him.” A face revealed a person’s character and disposition, if one was skilled in reading it, and physiognomists, natural scientists expert in the field, hoped, like curious people everywhere, to discern from it why human beings acted as they did and to predict what they may do in the future. Criminals especially—they felt certain they could determine them.

The science is archaic, kind of silly, but I understand the belief, even the point: a face lives in the open, naked, except when, for example, women wear veils or are veiled on specific occasions, such as marriage ceremonies. Expressions of happiness and remorse, pleasure and pain etch a mutating portrait. A face changes, none stay the same, except for a girl kept in captivity by her parents from the age of three, and, when she was discovered at the age of sixteen, she appeared to be a child, her face unmarked by experience. She had only known her room, a stunted world. Her growth was also stunted.

Cosmetic surgery manifests a wish for permanent disguises, “to fool” death, which makes life temporary and all acts conditional.

What Carlyle believed isn’t far from what portrait photographers or artists do, since their art concerns readings, of faces, stances—e.g., Richard Avedon, Rineke Dijkstra, Roy DeCarava, Collier Schorr, Lyle Ashton Harris, Diane Arbus, Lorna Simpson. Their pictures reveal a tacit belief in physiognomy, that faces should be read and looked at closely, even though faces don’t reveal character.

Whistler on his portrait of his mother: “To me it is interesting as a picture of my mother; but what can or ought the public to care about the identity of the portrait?”

The divine face. Divination and divining. The facial divide. Ha.

In the field, we “make” pictures by assembling from and interpreting the images given us. Making sense makes/allows for interpretation.

Are we ethnographers fooled or do we only fool ourselves? Margaret Mead’s Samoan girls told her what she wanted to hear, which is instructive, when we know it’s going on. Actually, it was a kind of gift to Mead, but I don’t do gifts—anthropologically, I mean.

The world is wired. Remote has several meanings.

The shift from analog to digital, for instance, has and will have so many unforeseen consequences. The hand disappears further; tangibility and physicality too. Unmanned drones are just part of the removal, the remoteness, future living has in store.

You are here, you wander there, fear of the Conradian monster within, at home and away. Though “away” can be home.

family images

Hour-long dramas are sustained on TV, but totally losing ground, because of the Internet, which is displacing TV, and theaters; there are far more sitcoms on TV, because the half-hour = more advertising dollars. Thirty minutes is about twenty-two minutes; in that time, a lot must happen to advance the story and keep a viewer’s attention; much must be tantalizingly not told, or withheld, secrets to compel viewers to watch next week. Reality TV uses the same narrative devices: who will be the biggest loser, winner, etc., is revealed over time, and time, its extension and duration, is what differentiates narrative from other art forms.

Sitcoms, like families, depend upon consistency of their members/characters, but TV needs comedy in its dramatized horrors, the kind actual families don’t experience. Characters must be “themselves” but also develop (the way actual characters don’t). Development in TV narratives folds into plots: Modern Family’s gay male couple adopt a Vietnamese baby girl and later plan their wedding. Viewers watch their almost-believable, always exaggerated, and bizarre machinations around these events. Psychological changes get embedded, when they do, through the protagonists’ relationships to events, not the other way around. Occasionally, both are in sync. Protagonists who go wildly out of character are scripted for actors to leave the show, or their characters die. An audience demands of a TV sitcom or long-running story a commitment to continuity and fidelity, to reasonableness, and a consolatory ending—a contract ensues. Dallas blew off the lid of credibility, when one entire season was the dream or fantasy of one of its protagonists. The Sopranos’s ambiguous finale infuriated and frustrated some viewers. The show has, for some (me), never ended, just like other tragedies eternally resonate.

The family’s contract, though, expected, implicit, or inherent, is to keep its secrets. In Breaking Bad, Walter White says his cooking meth and making millions is for the family; his wife, Skyler, hides his secret as long as she can, to protect their children and benefit from the drug money. Secrets are essential to the kinship bond and to husbands and wives, who don’t have to testify against each other in court, anyway. What happens in the family stays there: No Silence = No Protection.

I use media to explain certain phenomena and enduring characteristics, as well as new adaptations, of the American family. For example, Mafia movies succeeded after the family was hammered during the sixties, by promoting oaths that, like marriage, were ’til death do us part, while guilt and criminality occurred only by disregarding the family, not the law. Hollywood and indie movies glorified thugs’ loyalty to the clan, but The Sopranos portrayed mob boss Tony Soprano’s sadism so graphically that, Sunday by Sunday, the viewer’s sympathy was shredded. Still, violence was enshrined, and, with it and its threat against disloyalty, families were meant to cohere.

The American family sustains itself and mutates along with its movies, TV, reality, comedy, sitcoms, photographs, video, miniseries. Old genres for new ethnicities, types—easy makeovers—fill our many screens. With no end to war and cop stories, big and little monsters for an age of permanent war, and, with the cry for blind patriotism, an American’s fidelity to family can be converted into uncritical devotion to country or town.

A family member’s self-interest can break a contract, implicit or explicit, in the name of honesty (often a dubious motive, except in the case of the Unabomber’s brother and sister-in-law: their disloyalty saved lives), to cure the family or to get just desserts.

an art gallery in los angeles modeled

on the unabomber cabin

A new space by collector and artist Danny First may just take the weirdness cake.

First has built a 10-by-12-foot gallery in his Hancock Park backyard using the exact shape and dimensions of Unabomber Ted Kaczynski’s Montana cabin—down to the plywood patches out front.

. . . First says this isn’t out of some weird tribute to Kaczynski and his anti-technology manifestos. It’s the shape and the scale of the building that he found compelling. “I’ve never even seen [Kaczynski’s] cabin in person,” First says. “It really has nothing to do with the Unabomber. The simplicity of the structure is something that appeals to me—it’s like something that a kid would draw. I liked it from the first time I saw it on television.”

—Los Angeles Times

growing up is crazy

I totally knew about possessions, and consumption, even obsession, without knowing I knew it, because of John Maurice Stark. Father wanted things, he collected things, because he could. “His things” were his possessions, and a notion developed in me, Zeke Stark, that I was pure of heart, and he was crude and grasping. Later, I learned the word “materialist.” He was one—a spirit enemy.

To be possessed, but not possess life. Surrounded by materialists, I partook, resigned, acceding to the pathos of consumables. Pathetic. Working against that. Spirit as substance.

I studied Father taking pix. He set up a shot, camera to eye, pressed the button, pulled the film out, waited like a scientist, and the chemicals acted, or “did its thing,” as he liked to say. Then, wow, emergence! The image would appear on the surface, risen! There it was. He showed us “the result,” as he called it.

Father = the Polaroid speed of life. A slice of a tiny moment, but then you waited to see that moment, as if it hadn’t happened. It was so weird, we watched what we were doing as if we hadn’t done it, and now we could see what it was, a magic act that showed how reality might be deceptive—I mean, what would be shown that we hadn’t seen or experienced (see spirit photography).

The emerging, part of its happening, happened as we watched. And, every moment you waited for the past to show itself was lost, not present. Like a caterpillar out of a cocoon, the emergence excited me more than the picture. It was a white door he shot, a normal thing, but the magic of its chemistry, way more cool.

In his book America, Jean Baudrillard wrote of the Polaroid as a heightened form of photography’s uncanniness: “To hold the object and its image almost simultaneously as if the conception of light of ancient physics or metaphysics, in which each object was thought to secrete doubles or negatives of itself that we pick up with our eyes, has become a reality. It is a dream. It is the optical materialization of a magical process. The Polaroid photo is a sort of ecstatic membrane that has come away from the real object.”

I learned my way around a darkroom, developing a picture, learning patience—the new magic until that ended, too. Darkroom days ended, mostly for everyone, but some artists keep at it; the preciousness of historical prints will count even more with time.

shoot me but don’t shoot me

Mother didn’t like Father to snap her, as she put it, because he didn’t let her snap him. “Don’t shoot my face,” she’d say. It was a power thing.

Snapshots: an old concept.

Snapshots; snap judgments.

I’ll do it in a snap.

OH, SNAP.

Mother never accepted or believed women were inferior to men. It didn’t occur to me, either, but Father’s undermining her must have contributed to some negative internalizing. Father claimed he was a male feminist, but he was a condescending asshole contented with his bona fides: as he said again and again, he’d PARTIED, smoked it up, did some speed, and when he matured, he got real, studied law, settled down and married a woman better than he was, became an upstanding citizen, or a selfish, middle-class jerk-wad.

Mother explained: many women bought that the home was their rightful place, her mother did, but her mother was very angry and took it out on her and Clarissa, with the silent treatment, white rage, Mother called it. Then, in 1963, when Mother was in college, The Feminine Mystique hit the stands, and a lot changed, she said, very fast. Oh, the times they were a changin’. For a radical few of them, there wasn’t a need to overcome what they felt was injustice and personal loss; she and her friends felt on track to equality. But people can’t lose what they never had, she said. Mother shot me her spooky gravitas look, the mother knows BEST and MORE expression. Ping! Which totally refers to my current story; but I don’t want to get ahead of myself, I mean, if that’s ever possible. No kidding.

we the picture people

Words make images.

People make words, words make people.

People make images. Words and images make people.

How many fallacies fit on the head of a pin.