Chapter 11

The Return of Cupid

RENAISSANCE PAINTERS AND SCULPTORS, UNLIKE THEIR MEDIEVAL predecessors, looked to the Greeks and Romans for their artistic models. When illustrating the subject of romance, artists resurrected the figures of Venus and Cupid, who soon shunted the heart icon to the side.

Cupid’s mother was Venus, the goddess of love, but his paternity was less certain. Usually it was ascribed to Mars, the god of war, or Mercury, the god of merchants and messengers, and less frequently to Vulcan, the god of metalworking, who was Venus’s cuckolded husband. It was understood that Cupid took after his mother and that they were the primary catalysts of desire. With his trusty bow and arrow he sent darts of love into the hearts of young and old. In classical antiquity he was represented as a strong, winged, naked youth. In Renaissance art he became even younger, a child or baby. Why settle for the heart symbol when artists could represent the erotically charged flesh of Venus and Cupid?

Hearts were not pictured on objects produced in Renaissance Italy to celebrate betrothals and weddings; instead, mythological or biblical scenes were painted or carved on the obligatory cassone (marriage chests) given to a bride at the time of her wedding and permanently on display in the bed chamber. Family arms, not hearts, decorated maiolica plates and bowls; some carried images of couples in profile facing each other or clasped hands with the inscription fede (faith). The heart was notably absent from the magnificent oil paintings that became the hallmark of Renaissance and baroque high culture. For some artists it was only a pleasing shape, to be used among other decorative elements.

Raphael and his assistants, for instance, included small hearts among cupids and other mythological figures, birds, owls, snails, and various grotesques on the spacious surface of the Loggetta, a small washroom made for Cardinal Bibbiena at the Vatican in 1519. Within such mixed company the heart’s amatory message was definitely diminished.

YET THE HEART’S CONNECTION TO LOVE NEVER COMPLETELY disappeared, and during the Renaissance it manifested itself in unexpected places. A woodcut made early in the sixteenth century during the reign of the French King Francis I celebrated two kinds of love in a single heart—the amorous love implicit in the union of a royal couple and the king’s religious love for the Virgin Mary. To honor the king’s engagement to Eleanor of Austria, the woodcut shows Francis and Eleanor on each side of Mary and the infant Jesus, asking for their blessing. Francis holds a neatly drawn heart in his hand, and Eleanor holds flowers. Though the marriage never took place and Francis eventually married another, the woodcut continued to be popular in France. Because he looks directly at Eleanor and lifts up his heart in the familiar pose of a lover, he seems to be offering it to her as much as to Mary. Here the heart simultaneously represents both sacred and profane love.

Two Italian editions of the poet Petrarch’s sonnets, one from 1544 and the other from 1550, carried hearts on their title pages; these hearts, resembling pitchers, contained busts of Petrarch and his beloved Laura facing each other. Sometimes in Renaissance illustrations Venus herself held a flaming heart in her hand, but for the most part she stood or reclined on her own or was accompanied by her playful son Cupid.

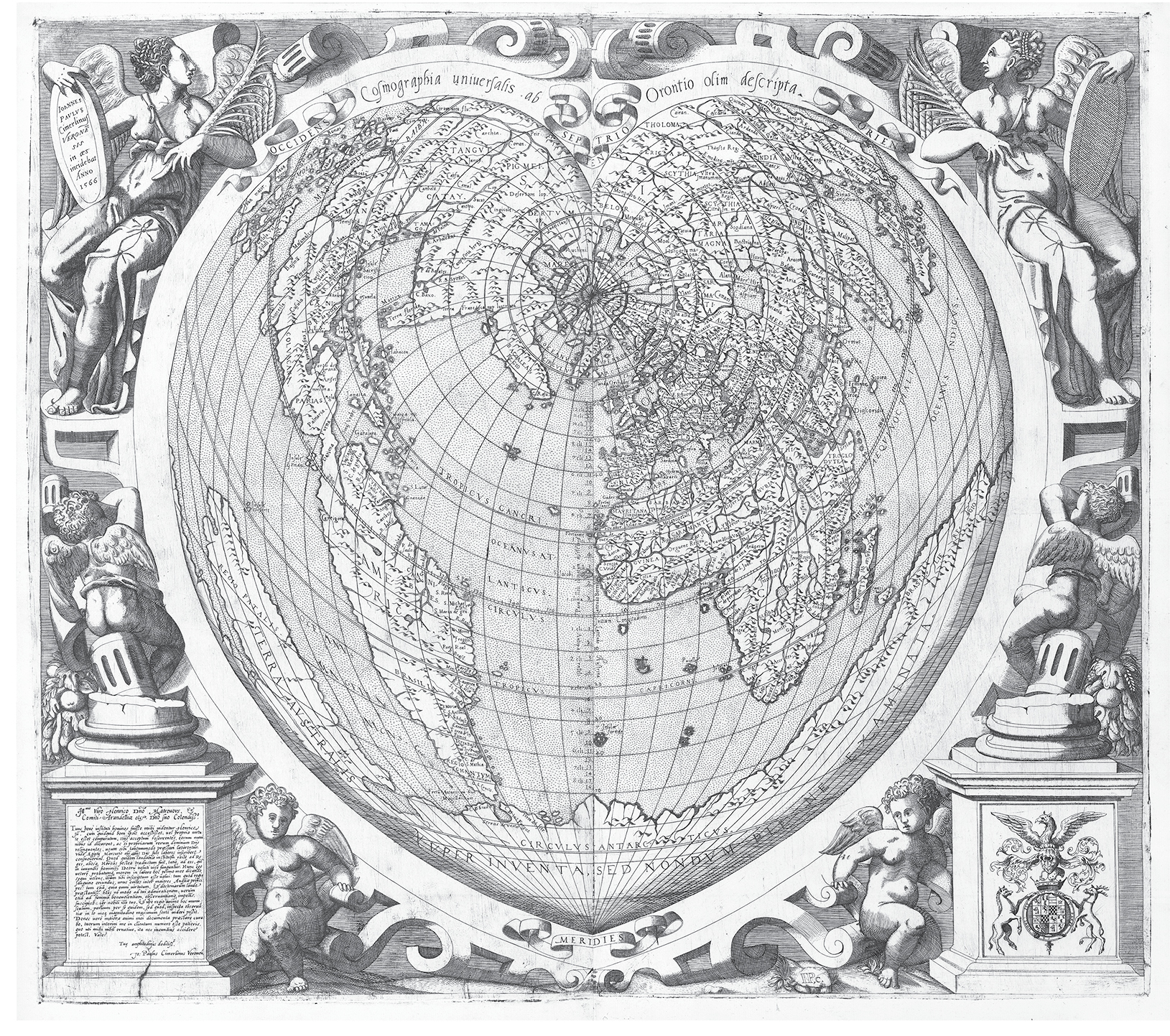

A more unlikely use of the heart occurred in maps. Heart-shaped maps of the world, called cordiform by cartographers, appeared in Europe early in the sixteenth century. Those surviving from this period are exquisitely detailed and often show the latest geographical discoveries, including America. Maps of a heart-shaped world may have been related to the concept that personal emotions, most notably love, can even affect the physical world.

The map labeled as Figure 21 was made by the Veronese artist Giovanni Cimerlino in 1566. It is encircled by the gods of love—four nude putti or cupids at the bottom and two Venus-type figures at the top. As I stare at this map and think of a world imbued with love, the words of a twentieth-century song keep circling in my head: “It’s love that makes the world go ’round, world go ’round, world go ’round.” Would that it were so!

THE PROMINENCE OF CUPID AS A RIVAL TO THE HEART IS especially noticeable in the emblem books that began to appear during the 1530s. A new literary form that brought together short texts with illustrations, emblem books were intended to convey a moral truth. They typically contained a motto, a picture, and a poem. The text often appeared in both Latin and the vernacular, and some editions were polyglot, which made for a truly pan-European phenomenon. Many emblem books took love as their overall theme, but it was a new kind of love. Instead of heartfelt fervor, emblem books praised temperate love in marriage, advised wives to be faithful, and counseled the love of one’s children. They took a dim view of unbridled passion, replacing it with the steadfast virtues of conjugal affection.

Thus, in the very first French emblem book, Andrea Alciato’s Livret des Emblèmes of 1536, we find an emblem titled De morte et amore (On Death and Love) showing an old man lying on the ground with an arrow in his chest, obviously the work of Cupid, and the skeletal figure of Death hovering beside him. The moral is clear: this is what happens to an old man who has the misfortune of being struck by Cupid’s arrows. In contrast to these frightening pictures, emblems extolling marital fidelity and parental love were accompanied by scenes of happy couples with flowers, dogs, and birds.

Emblem books reflected the new values promoted by Renaissance humanists and religious reformers. Turning their backs on the all-or-nothing passion characteristic of medieval romance, they looked to certain Roman writers, such as Horace, Virgil, Seneca, and Cicero, for more sober models. They aimed at convincing young people that carnal love is perilous and that only conjugal love can result in long-term happiness.

Instead of offering one’s heart to another in a gesture of selfless abandon, the would-be lover was advised to be wary of Cupid. However cute the winged cherub appeared to be, his defining attribute was his deadly bow and arrow. Hardly a benign creature, Cupid aimed his darts to inflict desire into the hearts of the unwary. If it didn’t literally kill you, unrestrained passion could bring about psychological, moral, and spiritual death.

AROUND 1600 A CIRCLE OF HUMANISTS AT THE UNIVERSITY of Leiden began to produce emblem books on the theme of love for the Dutch market. Surprisingly, though Leiden was known to be an austere Calvinist city, libidinous love poets, such as Ovid and Catullus, inspired their books. These sophisticated Dutch intellectuals were interested in exploring the nature of amorous love, how it began and developed, what kept it alive, and what destroyed it. They granted love a necessary role in natural law and lauded its virtues but also called for moderation as a means of warding off the destructive consequences of wild lust.

The philologist Daniel Heinsius, a professor and editor of classical texts, is credited with having written the first Dutch emblem book on love, Quaeris quid sit Amor? (Do You Ask What Love Is?), published anonymously in 1601 and republished in 1606/07 under the title Emblemata amatoria (Love Emblems). This book paved the way for several similar publications, most notably, in 1608, Otto Vaenius’s Amorum Emblemata (Emblems of Love), which has been called “the most important of all love emblem books.”

Vaenius enlisted a group of humanists and men of letters to contribute poems in various languages—Italian, Dutch, English, and French—each a loose translation of Latin texts taken mainly from Ovid. (Some later editions included German and Spanish translations.) He himself wrote some of the Dutch poems, but the unique strength of the book lies in Cornelis Boel’s 124 engravings. Each of these engravings, except one, features the figure of Cupid.

As in a running comic strip or graphic novel, Cupid is engaged in a multitude of human activities. In the emblem pictured in Figure 20, two playful Cupids are shooting arrows into each other’s hearts. The accompanying poem tells us, “The woundes that lovers give are willingly receaved, / When with two dartes of love each hits each others harte.” In other emblems we see Cupid tenderly embracing another Cupid, walking with Hercules as his guide, covering his ears to the trumpet of fame, stealing a bite to eat, prodding a sluggish turtle, leaning upon a steady oak in a storm, mixing butter, hunting deer, reading a love letter, carrying a candle, plucking roses, crying tears of love, treading on the tail of a proud peacock, wrenching a sword from the hand of Mars, carrying fresh flowers in each hand, and, of course, shooting his arrows into the chests of numerous victims. Pictured in so many different guises, Cupid comes across as an indefatigable and mischievous emissary of amorous love.

With the help of his contributors, his engraver, and his printer, Vaenius created a best-selling love manual. The epigram above each poem and the four-lined quatrains that followed not only proclaimed the power of love but generally lauded it. Consider the following exemplary headings:

Nothing resisteth love

Love is not to bee measured

Love is the cause of virtue

All depends upon love

Love is author of eloquence

Love pacifyeth the wrathful

Loves harte is ever young

Specific advice for the male lover was spelled out in the poems under the following headings:

Love grows by favour.

Perseverance winneth.

Fortune aydeth the audacious.

Out of sight out of mynde.

The chasing goeth before the taking.

Loves ioy is renuyed by letters.

Love enkindleth love.

Amorous love is generally presented in this book as a beneficent universal force. The emblem titled “All depends on love” shows Cupid aiming his darts at a globe in the distant sky, a globe that has already been struck with numerous arrows. The text tells us that this little god of love pierces the heavens and earth with his arrows and establishes “musicall accord” throughout the world, “For without love it were a chaos of discord.”

Relatively few of the poems in Amorum Emblemata focus on love’s sorrows. Among those that do, the emblem “No pleasure without payn” repurposes the old trope that all roses come with thorns. We rarely see gruesome pictures of Cupid’s victims, as in some other emblem books. Even when Cupid is pointing his arrow at a target placed on the chest of a young man, it looks more like a game than a killing. Yes, the heart is still the recipient of Cupid’s arrows—“Right at the lovers hart is Cupids ayme adrest.” But though it is mentioned frequently in the text, the heart itself is nowhere pictured in Vaenius’s collection.

WHILE CUPID DOMINATED VAENIUS’S AMORUM EMBLEMATA and similar works, a few emblem books did feature the heart symbol in his stead. Jean Jacques Boissard’s Emblèmes mis de latin en françois (Emblems Translated from Latin to French) (1595) updated the heart’s meaning, drawing on Greek and Roman classics. In a plate titled Libertas Vera est Affectibus non servire (One Is Truly Free Who Is Not Captive of His Passions), a helmeted man grasps a heart with a pincer while a woman holds scales to weigh it. The weighing of the heart, a measure of one’s worth going back to the Egyptian Book of the Dead and the medieval German Medallion Tapestry, now had a new purpose: moderation. The heart must submit to decorum and good judgment. Boissard argued that you cannot be free if you are ruled by your passions—a sensible philosophy modeled on the work of Latin thinkers such as Seneca rather than the immoderate Ovid. Boissard warned that the person with a generous heart must avoid being carried away by “the force of voluptuousness.” Only one “who balances his affections, measures his thoughts, speech, and acts, and moderates the passions of his soul” will achieve contentment and wisdom. We are clearly far removed from the all-or-nothing cries of medieval lovers.

Some emblem books were decidedly wary of the amorous heart. In such works the heart was shown pierced, burning, tormented—suggesting the perils of erotic love. The title page of Pieter Cornelisz Hooft’s Emblemata amatoria: Afbeeldingen van minne (Emblems of Love, 1611, 1613) has a picture of a flaming heart perforated from front to back by an unusually sharp-looking arrow.

A more positive vision of the amorous heart appeared around 1618 in a little Dutch volume titled Openhertighe Herten (Openhearted Hearts). With sixty-two etchings and matching poems, the book became a publishing success not only in Dutch but also in French and German editions.

The title page established the tone for the entire work. It shows a plump vessel or pitcher-type heart set above a heart-shaped scroll (a similar heart appears in every subsequent illustration). A loving couple stands on each side of the page. To the right there is a lower-class man and woman, she all but obscured by his large presence except for her head and shoulder. He holds his heart upright in his right hand. On the other side there is a fashionably dressed upper-class couple. She stands in front of the man, covering up most of his body. In her hands she holds a fan and a book while the man holds a large “pin” or “prick” above the lady’s book.

This “pin” or “prick” was used in a popular party game, which followed a prescribed sequence: each participant would place the pin randomly in an emblem book, read the emblem, and then solicit discussion. The foreword to Openhertighe Herten recommended the game for “all young people and honest company, at dinners and on other occasions to pass the time and avoid irregularities.” To play, “one keeps the little book shut, another pricks into it, between the page, with a bodkin or needle, and if the latter does not find the inclinations of his heart, another member of the company may.” Such amusement may seem tame to us today, but four hundred years ago it had great appeal among Dutch burghers.

All sixty-two emblems in Openhertighe Herten argued in favor of the “open heart” as the best approach to love and life, meaning that lovers should be honest and transparent with each other. Emblem number one of the French version shows a convex heart representing a house with a large latticed window at its center. The epigram tells us that the speaker’s heart, like an open window, “has never been false nor treacherous.”

The heart icon and Cupid continued to have their followers among artists depicting amorous love. But increasingly during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries Christianity encroached on the terrain of the secular heart. Both Catholics and Protestants claimed the heart icon and found different ways of making it their own.