Sylvia Plath with her mother and her brother, 1950

Richard Sassoon during his senior year at Yale

At home, the summer of The Bell Jar, 1953

The summer of 1954, the year after her breakdown

Senior year at Smith, 1955

At home in Cambridge, winter 1956–57

Plath and Hughes in Yorkshire, 1956

Spring 1959

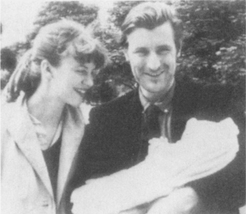

Sylvia and Ted with their daughter, Frieda, 1960

Plath with Frieda, London, 1960

Plath in Devon with Frieda and Nicholas, March 1962

Plath with Nicholas, December 1962

First of all? Keep quiet with Ted about worries. With him around, I am disastrously tempted to complain, to share fears and miseries. Misery loves company. But my fears are only magnified when reflected by him. So Mr. Fisher called tonight & is coming to sit in on my class Friday. Instead of complaining to Ted, feeling my tension grow, echoed in him, I am keeping quiet about it. I will make my test of self-control this week being quiet about it till it’s over. Ted’s knowing can’t help me in my responsibility. I’ve got to face it & prepare for it myself. My first day of Lawrence. Wednesday & Thursday to prepare for it. Keep rested. That’s the main thing. Make up a couple of little lectures. Get class prepared.

The main thing is to get on top of this preparation. To figure how to start teaching them about style. For the first lesson, make up general lectures about form of papers, organization, read from papers. Don’t get exasperated. A calm front: start at home. Even with Ted I must learn to be very calm & happy: to let him have his time & not be selfish & spoil it. Maturity begins here, however bad I am. I must prepare lectures, however poor.

January 4, 1958. New Year four days gone, along with resolutions of a page a day, describing mood, fatigue, orange peel or color of bathtub water after a week’s scrub. Penalty, and escape, both: four pages to catch up. Air lifts, clears. The black yellow-streaked smother of October, November, December, gone and clear New Year’s air come—so cold it turns bare shins, ears and cheeks to a bone of ice-ache. Yet sun, lying now on the fresh white paint of the storeroom door, reflecting in the umber-ugly paint coating the floorboards, and shafting a slant on the mauve-rusty rosy lavender rug from the west gable window. Changes: what breaks windows to thin air, blue views, in a smother-box? A red twilly shirt for Christmas: Chinese red with black-line scrolls and oriental green ferns to wear every day against light blue walls. Ted’s job chance at teaching just as long and just as much as we need. $1000 or $2000 clear savings for Europe. Vicarious joy at Ted’s writing, which opens promise for me too: New Yorker’s 3rd poem acceptance and a short story for Jack and Jill. 1958: the year I stop teaching and start writing. Ted’s faith: don’t expect: just write; listen to self, scribble. Fear about that: dumb silence. Yet: so what? It will take months to get my inner world peopled, and the people moving. How else to do it but plunge out of this safe scheduled time-clock wage-check world into my own voids. Distant planets spin: I dream too much of fame, posturings, a novel published, not people gesturing, speaking, growing and cracking into print. But with no job, no money worries, why, the black lid should lift. Look at life with humor: easy to say: things open up: know people: horizons extend.…

Night visions: the fire and coughing—zebra stripes of light laid on walls and angled ceilings from venetian blinds: Falcon Yard: rise above pure central line diary—lyric cry, no: but rich, humorous satire. Reconstruction.… Tables to bump into. Cameo—clear perspectives. Get back to perfect rhythms and words binging and bonging in themselves: green, thin, whine.…

The moment I stop, stop the itch of dreams and dream-lulling, squirrelish money-counting, paralysis sets in: paralysis of alternatives: to make up a scene? to describe a childhood incident by memory? I have no memory. Yes, there was a circle of lilac bushes outside Freeman’s yellow house. Begin there: 10 years of childhood before the slick adolescent years, and then my diaries to work on: to reconstruct. Two poplar trees, green and orange striped awnings. I never learned to look at details. Recreate life lived: that is renewed life. The incident goes down, a grit in the eye of god, and is wept forth a hundred years and a day hence, a globed iridescent pearl world. Turn the glass globe and the snow falls slowly through ronds of quartz air. Metaphors crowd. Pellets of fact drop into the mind’s glass of clear liquor and unfold petal by petal, red, blue, green, or pink and white—paper flowers creating an illusion of a world. Every world crowns its own kings, laurels its own gods. A Hans Andersen book cover opens its worlds: the Snow Queen, blue-white as ice, flies in a sleigh through her snow-thick air: our hearts are ice. Always: sludge, offal, shit against palaces of diamond. That man could dream god and heaven: how mud labors. We burn in our own fire. To voice that. And the horror: the strange bird who knows Longfellow, perches on a wire with a backdrop of English green-bushed landscapes. The white-bearded grandfather drowning in the sea-surge, the warm, slow, sticky rollers; the terror of paper crackling and expanding before the burnt-out black grate: whence these images, these dreams? Worlds—shut off by car-bustle, calendar-dictation. A world hung in a Christmas ornament, washed gilt, a world silvered and distended in the belly of my pewter teapot: open Alice’s door, work and sweat to pry open gates and speak out words and worlds.

Each day an exercise, or a stream-of-consciousness ramble? Hates crackle and brandish against me: unsettling the image of brilliance. My face I know not. One day ugly as a frog the mirror blurts it back: thick-pored skin, coarse as a sieve, exuding soft spots of pus, points of dirt, hard kernels of impurity—a coarse grating. No milk-drawn silk.… Hair blued with oil-slick, nose crusted with hair and green or brown crusts. Eye-whites yellowed, corners crusted, ears a whorl of soft wax. We exude. Spotted bodies. Yet days in a dim or distant light we burn clear of our shackles and stand, burning and speaking like gods. The surface texture of life can be dead, was dead for me. My voice halted, my skin felt the pounds and pounds, pressure of other I’s on every inch, wrinkled, puckered, sank in on itself. Now to grow out. To suck up and master the surface and heart of worlds and wrestle with making my own. To speak morally, for it is a moral. A moral of growth. Fern butting its head on concrete of here and now and ramming its way through. To get the faces, bodies, acts and names and make them live. To live as hard as we can, extending, and writing better. This summer: no job, or only very part-time job. German study and French reading. Reading own books: Berkeley, Freud, sociology. Most of all: myths and folk-tales and poetry and anthropology. History even. Knowing Boston. Boston diary: taste, touch, street names. Six o’clock rings, belling from the church where all the funerals come. Rooms. Every room a world. To be god: to be every life before we die: a dream to drive men mad. But to be one person, one woman—to live, suffer, bear children and learn other lives and make them into print worlds spinning like planets in the minds of other men.

… How everything shrinks on return—you can’t go home again: Winthrop shrunk, dulled, wrinkled its dense hide: all those rainbow extensions of dreams lost luster, shells out of water, color blanching out. Is it that our minds colored the streets and children then and do so no longer? We must fight to return to that early mind—intellectually we play with fables that once had us sweating under sheets—the emotional, feeling drench of wonder goes—in our minds we must recreate it, even while we measure baking powder for a hurry-up cake and calculate next month’s expenses. A god inbreathes himself in everything. Practice: Be a chair, a toothbrush, a jar of coffee from the inside out: know by feeling in.

Tuesday night, January 7. All day, or two days, you lay under the maple table and heard tears, phones ring, tea pouring from a pewter pot. Why not lie there until you rot or get thrown out with the rubbish, [the] book? A wreck on a shoal, time and tears vicissituding round about you, surging and sliding cool and blue-distant. Lie there, catching dust, pale rose and lavender scruff from the rug, blank-paged, and my voice quiet, choked in. Or to pass on air, blown with the other cries and complaints, to some limbo in the far nebulae. Anyhow: by dint of squandering some ink here, after counting your pages, you should see me through to the spring, to my so-called liberty—from what I seem to know, but for what I can only dream. Writing stories and poems is hardly so farfetched. But talking about it hypothetically is grim: a thing. Today, outside now, snow descends. This is where I came in. Dry taps on window. A greenish light from the lamps and flakes blowing oblique in the cone of light. An auspicious beginning for work tomorrow. After sun all week. And my lectures as usual, to prepare tomorrow morning—felt and feel mad, petulant, like a sick wasp—cough still and can’t sleep till late at night, feel grogged and drugged till noon. Yet will I work and get through. One day at a time. After a brief bold encounter with Chas. Hill yesterday, blue and squinch-toothed, and his icy self, a call from Mr. Fisher and my stupid discussion this morning in the high white atticky study, all book-crammed, and his 7 volume novel in black thesis books with white lettering that I know must be so ghastly. The gossip. One gets sick trying to conjecture it. The eleven o’clock coffee break and the gossip. All the inferences: The Institution will regard you as irresponsible. Two-year conventions. Rot. I am in a cotton-wool wrap. All is lost on me—all double entendres. “I have divided loyalties,” I say. “I am your friend,” he says. “No one but me will tell you this. Oh, by the way, may I tell all this to Mr. Hill?” “I resigned twice,” he said. “Once because of gossip that I was sleeping with students. President Nielson called up and found there were 10 in my class: ‘Hell, Fisher, that’s too much even for you!’ ” Now he is living deserted by his 3rd Smith wife for his selfishness. His vanity is as palpable as his neat white mustache. “It’s all in your mind,” he says, “about anxiety. I have it from various sources.” If they deal in inference, hint, threat, double entendre, gossip, I’m sick of it. They mean vaguely well, somehow. But have no idea what is for my own good, only theirs. “What do you need to write?” Gibian asks over tea. Do I need to write anything? Or do I need time and blood? I need a full head, full of people. First know myself, deep, all I have gathered to me of otherness in time and place. Once Whitstead was real, my green-rugged room with the yellow walls and window opening onto Orion and the green garden and flowering trees, then the smoky Paris blue room like the inside of a delphinium with the thin nervous boy and figs and oranges and beggars in the streets banging their heads at 2 A.M., then the Nice balcony over the garage, the dust and grease and carrot peels of Rugby Street on my wedding night, Eltisley Avenue, with the gloomy hall, the weight of coats, the coal dust. Now this pink-rose-walled room. This too shall pass, laying eggs of better days. I have in me these seeds of life.

Sunday night, January 12. Fumings of humiliation, burned and reburned, heartburn, as if I could relive a scene again and over, respeak it, forge it to my own model, and hurl it out, grit into pearl. Grit into art. Blundering, booted, to the little coffee shop table, past muffled chairs, braced under draped coats. The intimate group of three, James leaving, black-haired, squinting, not speaking, air sizzling with unspoken remarks, “Do you really hate it here so much?” The pale British Joan, green-rimmed spectacles, green-painted fingernails, furred, with great dangling gold Aztec earrings, shaped like cubist angels, meaning remarks and meaning looks—Sally’s great flat pale hands, like airborne white-bellied flounders, backs freckled, gesturing, stub-nails enameled with gilt paint. Superior. Condescending. Rude pink white-mustached Fisher: “Shame on you,” grinning foolishly, pointing to red lipstick caked in a crescent on a coffee cup—“The mark of the beast.” All the back references to common experience—“Is this yours?”—persian-lamb fezzed Monas holding up a pale tan pig-skin pouch stamped in red and green and gold pattern. “No, I wish it were. Is it Susie’s? Is it Judy’s?” Parties. Dinners. Lady with fishy eyes. “It’s all in your mind,” Fisher says. “I have it from various sources.” In polite society a lady doesn’t punch or spit. So I turn to my work. Dismissed without a word from the exam committee, hearing Sally superciliously advising me not to tell my students questions, I am justifiably outraged. Spite. Meanness. What else. How I am exorcising them from my system. Like bile. See Aaron and get it out. See Marlies about exam and get it out. The girls stand by. Even the big, nasty, blank-faced [one] in her raccoon coat turned good, two and one-half hours of good talk Friday. Saturday exhausted, nerves frayed. Sleepless. Threw you, book, down, punched with fist. Kicked, punched. Violence seethed. Joy to murder someone, pure scapegoat. But pacified during necessity to work. Work redeems.

January 14, Tuesday.… Now I am uncaring, more and more, about Smith social life. I will lead my own: Sunday teas, dinners later for U. of M. teachers and my work. Even, I’ll try if the prose isn’t too bad. Poems are out: too depressing. If they’re bad, they’re bad. Prose is never quite hopeless. The poetry ms. came thumping back unprized from the $1000 contest. Who won? I’d like to know. The second defeat. Must watch where it goes the third time. But I got rid of my gloom and sulking sorrows by spending the day typing sheafs of Ted’s new poems. I live in him until I live on my own. Starting June 1st. Will I have any ideas then? I’ve been living in a vaccuum for half a year, not writing for a year. Rust gags me. How I long again to be prolific. To whirl worlds in my head. Will I promise for 150 more days how I’ll write, or take courage and start now? Something deep, plunging, is held back. Voice frozen.…

January 20, Monday. Wicked, my hand halted, each night at writing, I fell away into sleep, book unwritten in. Woke today at noon, coming drugged to the surface, after a lost weekend. All the deep rooted yawns. Plunged to the depths of my fatigue, and now: bushels of words. I skim the surface of my brain, writing. Prose now. Working over the kernel chapter of my novel, to crouch it and clench it together in a story. Friday night in Falcon Yard. A girl wedded to the statue of a dream, Cinderella in her ring of flames, mail-clad in her unassaultable ego, meets a man who with a kiss breaks her statue, makes man-sleepings weaker than kisses, and changes forever the rhythm of her ways. Get in minor characters, round them out. Mrs. Guinea. Miss Minchell. Hamish. Monklike Derrick. American versus British. Can I do it? Over a year maybe I can. Style is the thing. “I love you” needs my own language.…

Free now, of a sudden, from classes, papers. Half the year over and spring to come, I turn, selfish, to my own writing. Reading a glut of Sat Eve Post stories till my eyes ached. These past days I realized the gap in my writing and theirs. My world is flat thin pasteboard, theirs full of babies, odd old dowagers, queer jobs and job lingo instead of set pieces ending in “I love you.” To live, to gossip, to work worlds in words. I can do it. If I sweat enough.…

Jealous one I am, green-eyed, spite-seething. Read the six women poets in the New Poets of England and America. Dull, turgid. Except for May Swenson and Adrienne Rich, not one better or more-published than me. I have the quiet righteous malice of one with better poems than other women’s reputations have been made by. Wait till June. June? I shall fall rust tongued long before then. Somehow, to write poems, I need all my time forever ahead of me—no meals to get, no books to prepare. I plot, calculate: twenty poems now my nucleus. Thirty more in a bigger, freer, tougher voice: work on rhythms mostly, for freedom, yet sung, delectability of speaking as in succulent chicken. No coyness, archaic cutie tricks. Break on them in a year with a book of forty or fifty—a poem every ten days. Prose sustains me. I can mess it, mush it, rewrite it, pick it up any time—rhythms are slacker, more variable, it doesn’t die so soon. So I will try reworking summer stuff: the Falcon Yard chapter. Yet it is a novel chapter somehow: slack, uncritical. Too many characters in it. Must make some conflict. I am at least making more minor characters come alive.… Must avoid the exotico-romantico-glory-glory slop. Get in gem-bright details. What is my voice? Woolfish, alas, but tough. Please, tough, without any moral other than that growth is good. Faith too is good. I am too a puritan at heart. I see the back of the black head of a stranger dark against the light of the living room, band of white collar, black sweater, black trousers and shoes. He sighs, reads out of my vision, a floorboard creaks under his foot. This one I have chosen and am forever wedded to him.

Perhaps the remedy for suppressed talent is to become queer: queer and isolate, yet somehow able to maintain one’s queerness while feeding food and words to all the world’s others. How long is it since bull sessions about ideas? Where are the violent argumentative friends? Of seventeen, of yesteryear? Now Marcia is set in her dogmatic complacency [omission] … netted in by supermarkets, libraries, and job routine. Entertaining? Probably.… She shells some resentment under her brisk breezy talk. I am too simple to call it envy: “Do all your students think you’re just wonderful and traveled and a writer?” Acid baths. Given time … I’ll attack her next year and get at her good innards. Innocence my mask. It always was, in her eyes, I the great dreamy unsophisticated and helpless thus unchallenging lout-girl. She, so pragmatic, now markets and cooks with no more savoir faire than I, I wife my husband, work my classes and “write.” She remembers two things of me: I always chose books for the color and texture of their covers and I wore curlers and an old aqua bathrobe. To my roommate, with love.… I wonder if, shut in a room, I could write for a year. I panic: no experience! Yet what couldn’t I dredge up from my mind? Hospitals and mad women. Shock treatment and insulin trances. Tonsils and teeth out. Petting, parking, a mismanaged loss of virginity and the accident ward, various abortive loves in New York, Paris, Nice. I make up forgotten details. Faces and violence. Bites and wry words. Try these.

January 22, Wednesday. Absolutely blind fuming sick. Anger, envy and humiliation. A green seethe of malice through the veins. To faculty meeting, rushing through a gray mizzle, past the Alumnae House, no place to park, around behind the college, bumping, rumping through sleety frozen ruts. Alone, going alone, among strangers. Month by month, colder shoulders. No eyes met mine. I picked up a cup of coffee in the crowded room among faces more strange than in September. Alone. Loneliness burned. Feeling like a naughty presumptuous student. Marlies in a white jumper and red dark patterned blouse. Sweet, deft: simply can’t come. Wendell and I are doing a textbook. Haven’t you heard? Eyes, dark, lifted to Wendell’s round simper. A roomful of smoke and orange-seated black painted chairs. Sat beside a vaguely familiar woman in the very front, no one between me and the president. Foisted forward. Stared intently at gilt leaved trees, orange-gilt columns, a bronze frieze of stags, stags and an archer, bow bent. Intolerable, unintelligible bickering about plusses and minuses, graduate grades. On the back cloth a Greek with white-silver feet fluted to a maid, coyly kicking one white leg out of her Greek robe. Pink and orange and gilded maidens. And a story, a lousy sentimental novel chapter 30 pages long and utterly worthless at my back: on this I lavish my hours, this be my defense, my sign of genius against those people who know somehow miraculously how to be together, au courant, at one. Haven’t you heard? Mr. Hill has twins. So life spins on outside my nets. I spotted Alison, ran for her after meeting—she turned, dark, a stranger. “Alison,” Wendell took her over, “are you driving down?” She knew. He knew. I am deaf, dumb. Strode into slush, blind. Into snow and gray mizzle. All the faces of my student shining days turned the other way. Shall I give, unwitting, dinners? to invite them to entertain us? Ted sits opposite: make his problems mine. Shut up in public. Those bloody private wounds. Salvation in work. What if my work is lousy? I want to rush into print any old tripe. Words, words, to stop the deluge through the thumbhole in the dike. This be my secret place. All my life have I not been outside? Ranged against well-meaning foes? Desperate, intense: why do I find groups impossible? Do I even want them? Is it because I cannot match them, tongue-shy, brain-small, that I delude my dreams into grand novels and poems to astound? I must bridge the gap between adolescent glitter and mature glow. Oh, steady. Steady on. I have my one man. To help him I will.

Sunday night, January 26. A blank day of cooking and gusts of drowsiness. Mother gone on a broth of renewed communication: suddenly it comes over me—how much life is shuttered and buckled in the tongues of those we patronize and take for granted. “How did M’s madness come on her?” we asked. The dining room stood dark, windowless, guarding its shadows, and the two uneven red candles, one tall, one short, stuck into the green bottles, wax-crusted, made a tawdry yellow light, as candles do, warring against the faintest gray daylight. M. became a religious fanatic and one morning, shortly before Pearl Harbor, began to prophesy: she was Christ, she was Gandhi, she would not let her husband touch her. Mother listened to her, lying on her back, shut-eyed, with no food, no drink, talk, talk, talking for ten hours without a stop. A mental hospital for two years; [her husband]: “Stop chasing after butterflies and come home to take up your real responsibilities.” Relapses, setbacks. He and his “perfect marriage”—never once did she contradict him or counter his wishes. She, her own heroine, living sainthoods, martyrdoms, novel sagas. Married to the wrong man, twenty-one years older than she. [Omission.]

Oh, spring vacation. Sometimes, secure, I wonder we don’t stay here, Ted teaching (ho) at Amherst, or Holyoke (he has had inquiries from both) and me here. A joint income of $8 thousand. But even as I wake from the nice comfort, I see my own death, and his and ours smiling at us with candied smile: The Smiler. How a distant self must, vain and queenly, dream of being a great dramatic Dunn or Drew-type teacher, loved, wise, white-headed and wrinkled, a many-wrinkled wisdom.

I breathe among dry coughs and clotted noses. I must, on the morning coffee-surge of exultation and omnipotence, begin my novel this summer and sweat it out like a school year—rough draft done by Christmas. And poems. No reason why I shouldn’t surpass at least the facile Isabella Gardner and even the lesbian and fanciful Elizabeth Bishop in America. If I sweat the summer out.…

I want one [a baby]. After this book-year, after next-Europe-year, a baby-year? Four years of marriage childless is enough for us? Yes, I think I shall have guts by then. The Merwinsi want no children—to be free [omission]…. I will write like mad for 2 years—and be writing when Gerald and or Warren 2nd is born, what to call the girl? O dreamer. I waved, knocked, knocked on the cold window glass and waved to Ted moving out into view below, black-coated, black-haired, fawn-haunched and shouldered in the crisp-stamped falling snow. Fevered, how I love that one.

Jack and Jill rejection came. How I intuit ahead. No reason, but all my pink-potted dreams gone kaput. But with it a strange letter from ARTnews asking for a poem on art and speaking of an “honorarium” of $50–$75—a consolation prize? I shall submerge in Gauguin—the red-caped medicine man, the naked girl lying with the strange fox, Jacob wrestling with his angel on a red arena ringed by the starched white-winged caps of Breton peasant women. Oh, will this week end, to my one day, my Sunday, of rest? Will I somehow prepare my classes on Joyce, yet undone? I drive to the breaking point, but have tested and tried myself and only say: the end will come. A year to write in—to read Everything. Will it come and we do it? Answer me, book. Today: Matisse, exploding in pink cloths and vibrant rich pink shadows, pale peach pewter and smoky yellow lemons, violent orange tangerines and green limes, black-shadowed and the interiors: Oriental flowery—pale lavenders and yellow walls with a window giving out onto Riviera blue—a bright blue double-pear-shape of a violin case—streaks of light from the sun outside, pale fingers—the boy at the scrolled piano with the green metronome shape of the outdoor world. Color: a palm tree exploding outside a window in yellow and green and black jets, framed by rich black red-patterned draperies. A blue world of round blue trees, hatpins and a lamp. Enough. I shall sit and stare at Gauguin in the library, limit my field and try to rest, then write it. Don’t count gold hens before eggshell congeals.

Secret sin: I envy, covet, lust—wander lost, red-heeled, red-gloved, black-flowing-coated, catching my image in shop windows, car windows, a stranger, sharper-visaged stranger than I knew. I have a feeling this year will seem a dream when done. I have some great nostalgia for my lost Smith-teacher self, perhaps because this job is now secure, bitable-size, and the new looming “threat of a new life” in a new (for me) city at the one trade which won’t be cheated or “got-by” with patch-up jobs, waits, blank-paged: oh, speak. What then? What now? How much easier, how much smiling deadlier, to scrape and scrub a living off the lush trees of Joyce, of James. Morning, too, of Matisse odalisques, patterned fabrics, vibrant, blue-flowered tambourines, bare skin, breast-round, nipples-rosettes of red lace and the skirls and convoluted swirls of big palmy oaky leaves.…

… The new sense of power and maturity growing in me from coping with this job, and cooking and keeping house, puts me far from the nervous insecure miserable idiot I was last September. Four months has done this. I work. Ted works. We master our jobs and are, we feel, good teachers, natural teachers—this: the danger. The sense of elaborate exclusion, the unseeing gaze of Joan and calculated insolence and patronizing stance of Sally I shall be free from: I don’t like it, yet I don’t like them enough to court lost favor. When did the change come? With my bursting into tears in front of Marlies? Humiliations stomached like rotten fruit. I grow through them and beyond. My work must engross me these next four months—plays and poems, reading for [Newton] Arvin, working on a poem for ARTnews. Black-clad, I walk alone, and so what: caricature green-nailed Joan and pale freckle-spreckled Sally in stories. A new life of my own I shall make, from words, colors and feelings. The Merwins’ high Boston apartment opens its wide-viewed windows like the deck of a ship.

Sunday, February 9. Night nearing nine. Outside: laughter of boys, the brooom-brooom of a car revving up. Today spent itself in a stupor, twilit, fortified by coffee and scalding tea: a series of cleansings—the icebox, the bedroom, the desk, the bathroom, slowly, slowly ordering—trying to keep the “filth of life at a distance”—washing hair, self, stockings and blouses, patching the ravages of a week, reading to catch up with my first week of Hawthorne stories—writing, for the first time, a long letter to Olwyn,j feeling colors, rhythms, words joining and moving in patterns that please my ear, my eye. Why am I free to write to her? My identity is shaping, forming itself—I feel stories sprout, reading the collection of New Yorker stories—yes, I shall, in the fullness of time, be among them—the poetesses, the authoresses. I must meantime, this June beginning, learn about planets and horoscopes to be in the proper starred house: I’ll wish I had learned if I don’t: tarot pack, too. Maybe I should stay alone, unparalyzed, and work myself into mystic and clairvoyant trances. To get to know Beacon Hill, Boston, and get its fabric into words. I can. Will. Now to do what I must, then to do what I want: this book too becomes a litany of dreams, of directives and imperatives. I need not to be more with others, but to be more and more deeply, richly alone. Recreating worlds.… Now for a picture, enough of this blithering about calendar engagements: I am here: black velvet slacks stuck with lint, worn and threadbare slippers, dun-fuzzed with dark brown leopard spots on a pale tan ground, gilt bordered, then the polished blond-brown woodwork of the maple coffee table, the dull inner glow of white and silver highlights on the pewter sugar bowl with its domed lid and cupola peak, then the dented-red-skinned apples, mealy and synthetic tasting. Ted in the great red chair by the white bookcase of novels, his hair rumpled front, dark brown, but tighter than ever, and his face blue-greening along the jaw: Those faces he makes: owls, monsters: “The Man Who Made Faces”: a symbolic story? Who are we, really? In his dark green sweater, white and green banded at the cuffs, bent over the pink tablet, black trousers, gray socks of pale thick wool, shoes black, cracked, shining in the light. He poises, pen in right hand, propping his chin, elbow on the tablet and the chartreuse-shaded light behind him. All about, in a three-quarter circle, papers, airmail letters, books, torn pink scraps of tissue, typed poems. I, chilled, feel his warmth [omission] … haul me over to be held and hugged: HUG his shirts instruct, at the inner neckband, coming back from the laundry starched and bound. Another story for The New Yorker: the evocation of my seventeenth summer, the spurt of blood of my period and the twins painting the house, the farm work and Ilo’s kiss. A synthesis: the coming of age. A matter of moment: get M. E. Chase to tell me where to send New Yorker stories, to whom. I shall in a year do it.

I catch up: each night, now, I must capture one taste, one touch, one vision from the ruck of the day’s garbage. How all this life would vanish, evaporate, if I didn’t clutch at it, cling to it, while I still remember some twinge of glory. Books and lessons surround me: hours of work. Who am I? A freshman in college cramming history and feeling no identity, no rest? I shall ruminate like a cow: only that life and not before I am born: the windows jerk and sound in their frames. I shiver, chilled, the grave-chill against the simple heat of my flesh: how did I get to be this big, complete self, with the long-boned span of arm and leg? The scarred imperfect skin? I remember thick mal-shaped adolescence and the colors of my remembering return with a vivid outline: high school, junior high, elementary school, camps & the fern-huts with Betsy: hanging Johanna: I must recall, recall, out of the stuff is writing made, out of the recollected stuff of life.… “Get hold of a thing and shove your head into it,” Ted says just now. I weary and will take hot milk to bed and read more Hawthorne. My lips are drying, chapped, and I bite them raw. I dreamed I had long stinging scratches down the fingers of my right hand, but looking down saw my hands white and whole and no red blood-scabbed lines at all.

Tuesday, February 10.… How clear and cleansed and happy I feel. Why? Last night’s dinner cleared such air—Wendell an unexpected ally and miraculous gossip, so richly he held forth, and Paul and blond witchy dear Clarissa, her red mouth opening and curling like a petaled flower or a fleshly sea anemone, and Paul, gilded as always, but not quite so seedy, his blue eyes marred with red, his blond curls rough and Rossetti-like, cherubic, curling, his pale jacket and pale buff sweater setting off his gilt and gaudy head. Have I said I saw him running down the stairs of Seelye out into last week’s falling snow with a bright absinthe-green suit on that made his eyes the clear unearthly and slightly unpleasant acid green of a churned winter ocean full of icecakes? We talked, and I must never again start drinking wine before my guests come—I slowed, but sickened late. Till midnight they stayed and Wendell favored us with department secrets …

Tuesday noon.… I had a vision in the dark art lecture room today of the title of my book of poems, commemorated above. It came to me suddenly with great clarity that The Earthenware Head was the right title, the only title. It is derived, organically, from the title and subject of my poem “The Lady and the Earthenware Head,” and takes on for me the compelling mystic aura of a sacred object, a terrible and holy token of identity sucking unto itself magnetwise the farflung words which link and fuse to make up my own queer & grotesque world out of earth, clay, matter; the head shapes its poems and prophecies, as the earth-flesh wears in time, the head swells ponderous with gathered wisdoms. Also, I discover, with my crazy eye for anagrams, that the initials spell T-E-H, which is simply “to Edward Hughes,” or Ted, which is of course my dedication. I dream, with this keen spirit-whetting air, of a creative spring. So I shall live and create, worthy of Dr. B. and Doris Krook and myself and Ted and my art. Which is word-making, world-making. This book title gives me such staying power (perhaps these very pages will see the overturn of my dream, or even its acceptance in the frame of the real world). At any rate, I see the earthenware head, rough, crude, powerful and radiant, of dusky orange-red terra-cotta color, flushed with vigor and its hair heavy, electric. Rough terra-cotta color, stamped with jagged black and white designs, signifying earth, and the words which shape it. Somehow this new title spells for me the release from the old crystal-brittle and sugar-faceted voice of “Circus in Three Rings” and “Two Lovers and a Beachcomber,” those two elaborate metaphysical conceits for triple-ringed life—birth, love and deaths, and for love and philosophy, sense and spirit. Now pray god I live through this windy season and come into my own in June: three and a half months, how the year dwindles. To get through this week and thesis. I feel great works which may speak from me. Am I a dreamer only? I feel beginning cadences and rhythms of speech to set world-fabrics in motion. Let me keep my eye off publication and simply write stories that have to be written. We reject the Merwins’ flat: [Omission.] No thanks. We will perhaps stay here in June and stick up for top floor, light and a view, quiet and preferably furnished. Notes. Of [Bill] Van Voris:k pale with a mouth like [a] snail spread for sliding—a man who always keeps the expression on his face for a moment too long. My poems thin to a bare spare twenty, even those with quaint archaic turns of speech. How far I feel from them, from poems. Oh, to get in voice again, this book a wailing wall. What thoughts, few as they are, revolve in my head? The Doulde: The Earthenware Head (jutting forth from the African masks and doll masks on Mrs. Van der Poel’s screen, with their blank eyes rounded with phosphor circles, and then insect heads and diminutive pincer mouths)—how all photograph portraits do catch our souls—part of a past world, a window onto the air and furniture of our own sunken worlds, and so to the mirror—twin, Muse.

Thursday morning, February 20.… I want all my time, time for a year, the first year since I was four years old, to work and read on my own. And away from Smith. Away from my past, away from this glass-fronted, girl-studded and collegiate town. Anonymity. Boston. Here the only people to see are the twenty people on the faculty whom I just don’t want to see another year. Will I write a word? Yes. By the time I write in here again this ghastly day will be over, I having walked out my dreamy drugged state and given three classes, botched and unsure. The next three weeks, however, I shall prepare violently and fully a week ahead if it’s the last thing I do. Oh, resolves. The three red apples, yellow speckled, thumb-dinted brown, mock me. I myself am the vessel of tragic experience. I muse not enough on the mysteries of Oedipus—I, weary, resolving the best and bringing, out of my sloth, envy and weakness, my own ruins. What do the gods ask? I must dress, rise, and send my body out.…

A day in a life—such gray grit, and I feel apart from myself, split, a shadow, and yet when I think of what I have taught and what I will teach, the titles have still a radiant glow and the excitement and not the dead weary plod of today. I have gotten back the life-vision, whatever that is, which enables people to live out their lives and not go mad. I am married to a man whom I miraculously love as much as life and I have an excellent job and profession (this one year), so the cocoon of childhood and adolescence is broken—I have two university degrees and now will turn to my own profession and devote a year to steady apprenticeship, and to the symbolic counterpart, our children. Sometimes I shiver in a preview of the pain and the terror of childbirth, but it will come and I live through it.

Saturday night, February 22.… A scattered dull day—the answer to: what is life? Do we always grind through the present, doomed to throw a gold haze of fond retrospect over the past (those images of myself, for example, that floating April day in Paris in the Place du Tertre, wine and veal in sunlight with Tony, when I was without doubt most miserable before the horrors of Venice and Rome and the bloom of my best Cambridge spring and the vision of love) or ahead to the unshaped future, spinning its dreams of novels and books of poems and Rome with Ted out of a lumpish mist. [Omission.]

Sunday night, February 23. This must be the 26th February 23rd I have lived through: over a quarter century of Februaries, and would I could cut a slice of recollection back through them all and trace the spiraling stair of my ascent adultward—or is it a descent? I feel I have lived enough to last my life in musings, tracings of crossings and recrossings with people, mad and sane, stupid and brilliant, beautiful and grotesque, infant and antique, cold and hot, pragmatic and dream-ridden, dead and alive. My house of days and masks is rich enough so that I might and must spend years fishing, hauling up the pearl-eyed, horny, scaled and sea-bearded monsters sunk long, long in the Sargasso of my imagination. I feel myself grip on my past as if it were my life: I shall make it my future business: every casual wooden monkey-carving, every pane of orange-and-purple nubbled glass on my grandmother’s stair-landing window, every white hexagonal bathroom tile found by Warren and me on our way digging to China, becomes radiant, magnetic, sucking meaning to it and shining with strange significance: unriddle the riddle: why is every doll’s shoelace a revelation? Every wishing-box dream an annunciation? Because these are the sunk relics of my lost selves that I must weave, wordwise, into future fabrics. Today, from coffee till teatime at six, I read in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, drawn back again with the joy of a woman living with her own gamekeeper, and Women in Love and Sons and Lovers. Love, love: Why do I feel I would have known and loved Lawrence. How many women must feel this and be wrong! I opened The Rainbow, which I have never read, and was sucked into the concluding Ursula and Skrebensky episode and sank back, breath knocked out of me, as I read of their London hotel, their Paris trip, their riverside loving while Ursula studied at college. This is the stuff of my life—my life, different, but no less brilliant and splendid—and the flow of my story will take me beyond this in my way—arrogant? I felt mystically that if I read Woolf, read Lawrence (these two, why? their vision, so different, is so like mine) I can be itched and kindled to a great work: burgeoning, fat with the texture and substance of life: This my call, my work. This gives my being a name, a meaning—“to make of the moment something permanent”: I, in my sphere, taking my place beside Dr. Beuscher and Doris Krook in theirs—neither psychologist, priestess nor philosopher—teacher but a blending of both rich vocations in my own worded world. A book dedicated to each of them. Fool. Dreamer. When my first novel is written and accepted (a year hence? longer?) I shall permit myself the luxury of writing above: “I am no liar.” I worked on two pages of carefully worded criticism of the Lawrence thesis: feel I am right, but wonder as always: will they see? will they scornfully smile me into the wrong? No: I stated clearly my case and I feel there is a good case made. Cups of scalding tea: how it rests me. We walked out about seven into the pleasant mild-cold still night to the library: the campus snow-blue, lit from myriad windows, deserted. Cleared, cleansed, stung fresh-cheeked chill, we walked the creaking-cricking plank paths through the botanical gardens and while Ted delivered thesis and book I walked four times round the triangle flanked by Lawrence House, the Student’s Building and the street running from Paradise Pond to College Hall, meeting no one, secretly gleeful and in control, summoning all my past green, gilded gray, sad, sodden and loveless, ecstatic, and in-love selves to be with me and rejoice.…

Monday night, February 24. Weary, work not done, week scarcely begun: such mortal falls, the edge of heat keeps up so short a time. Yet today gathered into itself (approximating as it does the second anniversary [25th to be exact] of our meeting at the St. Botolph’s party and the anniversary of the acceptance of Ted’s book via telegram as winner of the NYC Poetry Center contest) some symbolic good joint-fortune. Mademoiselle, under the persona of Cyrilly Abels, wrote to accept one poem from each of us for a total of $60. Ted’s “Pennines in April” and my “November Graveyard”—spring and winter on the moors, birth and death, or, rather, reversing the order, death and resurrection. My first acceptance for about a year: I feel the swing into the freedom of June begin—shall doggedly send out remaining 5 or 6 poems until I find some home for the best: but this came, linking our literary fortunes in the best way: I must work to get a book of poems together by next February at least. Ted drove me through a warm wet gray despondent morning to Arvin’s lecture—I am sure I know The Scarlet Letter by heart. Then: good introduction to Picasso—blue period (old guitarist, laundress, old man at table) and the magnificent rose-vermilion-period saltimbanques, pale, delicate, poised and lovely. Don’t like the mad distortions of his forties with my deep self much—world of sprung cuckoo clocks—all machinery and blare and schizophrenic people parceled out in patches and lines like dead goods: macabre visual puns.… Arvin’s exam comes up with, in effect, a week of correcting for me to do. I am unfairly angry because I thought the job would pay $300, where it pays $100, and my art poem, if I wrote it, would almost meet, with hours of pleasure squandered, the sum. Faculty meeting long, smoky, controversial—Bill Scott, myopic, pale fallen-chinned physics professor very like the Mad Hatter with his bitten slice of bread and butter. Sometimes I wonder, are they all dodos? Surprises: Stanley “fired”—one year appointment ending next year: he volatile, enthusiastic, “immature”; they secretly jealous of him spending over a year on a non-academic project—a novel. What, alas, and hoho, must they think of me? A complete traitor. I go to buttress myself from snow in boots and woolens. Pray for my safe return.

Friday Night, February 28. Vinously blurred, letting lamb fat and blood congeal to pale grease on the scattered plates, wine sediment curd in the bottom of glasses. Today, for some reason blest, day done with, and the reward shining, of no extra preparation for tomorrow, and turning, wistful, toward writing—rereading the thin, thinning nucleus of my poetry book The Earthenware Head and feeling, proud, how steady are the few poems I am keeping on—a sure twenty, sixteen of them already published (except for the damn, damned dilatory London Magazine). Rereading my long excerpt “Friday Night in Falcon Yard,” too lumbering, leisurely, too artificial, too much in it: yet: this I will revise …

Sunday night, March 2. Again, late: it will be twelve before I sleep. A strange, stopped day: Ted and I having morning coffee—black and bitter-edged, with the Bramwells in their uncomfortable second-floor flat, chairs turned wrong-side-to, records scattered, white marble fireplace angular and functionless. James is leaving for their home in France tomorrow. Ted met him in the library yesterday, a few seconds before I came into the periodical room from my last class of the week: I looked into the room through the glass door before I opened it, saw no black-coated Ted, pushed the door open, saw James’s back in brown and white tweed coat, then Ted, dark, disheveled and with that queer electric invisible radiance he gives off as he did that first day I saw him over two years ago: to think, irony of ironies, that two years ago I was feverishly studying Webster & Tourneur for my supervisions (which very plays I am this week examining my students on) and furiously, desperately, talking myself into a crazy belief that I would somehow manage to see Ted and imprint my mark ineffaceably on him before he left for Australia and murder his pale freckled mistress named Shirley. Let all rivals forever be called Shirley. How, now, sitting here in the calm cleared living room where we have our ordered teas, I feel I have wrested chaos and despair—and all the wasteful accident of life—into a rich and meaningful pattern—the light through this door, into the dark dim pink-walled dining alcove, shines to our bedroom and bright from his writing of poems in the swept spacious bedroom the chink of light through the crack in between the doorframe and door betrays him to me: and suddenly all, or most, of that long 35-page chapter which should be—the events at least—the core of my novel seems cheap and easily come-by—all that sensational jabber about winds and doors and walls banging away and back. But that was the psychic equivalent of the whole experience: how does Woolf do it? How does Lawrence do it? I come down to learn of those two: Lawrence because of the rich physical passion—fields of forces—and the real presence of leaves and earth and beasts and weathers, sap-rich, and Woolf because of that almost sexless, neurotic luminousness—the catching of objects: chairs, tables and the figures on a street corner, and the infusion of radiance: a shimmer of the plasm that is life. I cannot and must not copy either. God knows what tone I shall strike. Close to a prose-poem of balanced, cadenced words and meanings, of street corners and lights and people, but not merely romantic; not merely caricature, not merely a diary: not ostensibly autobiography: in one year I must so douse this experience in my mind, imbue it with distance, create cool shrewd views of it, so that it becomes reshapen. All this—digression: James, the subject: yesterday, a broken man, his craggy sallow face, with its look of genial corrugated black lines—hair, brows, wrinkles and dark grain of shaven beard, his bright, mirthful black eyes—all seemed broken, askew. [Omission.] “When are you leaving America?” I felt impelled to ask first, meaning, of course, when in summer. “Monday,” he said. He can’t work here, can’t write here. He talked loudly, in an audible whisper, and I wanted to quiet him, and get out of there, with the dilly girls listening over their periodicals. A chink opened into his hell: what it must be to decide him to leave, and how absurdly vindicated I felt, remembering Joan’s mean-toned “Why are you going? Don’t you like it here?” How can James leave her? This always puzzles me. I need Ted … as I need bread and wine. I like James: one of the few men here whose life doesn’t seem available, processed in uniform, cellophane-wrapped blocks, like synthetic orange cheese: James has the authentic, cave aged, mold-ripened smell of the real thing. [Omission.] Joan seems young and thin for him. At coffee this morning he seemed restored, jovial. We talked of bulls and bullfights, after the two movies—on Goya and bullfighting—last night. I borrowed James’s autobiography and finished it tonight: 250 pages, The Unfinished Man—about his experiences as a conscientious objector during the war: desultory beginning, here, there, Stockholm, Finland and all told about, characters portrayed, not actually moving and talking on their own, but talked about, half-emerged, like a frieze of flushed marble. And women: he seems to run from them—his wife queerly in the background, diminishing to America, to divorce; his child evaporating. A “told-about” love affair with a queer Finnish girl, death-oriented, who commits suicide (was he to blame, partly? did it really happen?) and a rather illuminating statement that he (“like most men”) believes that loving a woman eternally isn’t incompatible with leaving her: loving, leaving—a lovely consonance. I don’t see it: and my man doesn’t. The quiet of midnight settles over Route 9. Already it is tomorrow and the days I cross off with such vicious glee—just as I toss with premature eagerness empty bottles of wine and honey into the wastebasket to be neat and clear of clogging half-full jars—are those of my youngness and my promise. I believe, whether in madness or in half-truth, that if I live for a year with the two years of my life and learning at Cambridge I can write and rewrite a good novel. Ten times this 35 page chapter and rewriting and rewriting. Goal set: June 1959: a novel and a book of poems. I cannot draw on James’s drama: war, nations, parachute drops, hospitals in trenches—my woman’s ammunition is chiefly psychic and aesthetic: love and lookings.

Monday night, March 3.… A chapter story from Luke’s novel arrived, badly typed, no margins, scrawled corrections, and badly proofread. But the droll humor, the atmosphere of London and country which seeps indefinably in through the indirect statement: all this is delicate and fine. The incidents and intrigues are something I could never dream up—unless, I add, I worked at it.… Nothing so dull and obvious and central as love or sex or hate: but deft, oblique. As always, coming unexpectedly upon the good work of a friend or acquaintance, I itch to emulate, to sequester. Got a queer and most overpowering urge today to write, or typewrite, my whole novel on the pink, stiff, lovely-textured Smith memorandum pads of 100 sheets each: a fetish: somehow, seeing a hunk of that pink paper, different from all the endless reams of white bond, my task seems finite, special, rose-cast. Bought a rose bulb for the bedroom light today and have already robbed enough notebooks from the supply closet for one and a half drafts of a 350 page novel. Will I do it.…

Wednesday, March 5.… I found the two pained and torturous typewritten sheets I wrote in October and November when trying to keep myself from flying into black bits—how new, now, is my confidence: I can endure—endure through weaknesses, bad days, imperfections and fatigue: and do my work without running away or crying: mercy, I can no more. If, knocking on wood (where does that come from?), I can survive in health till spring vacation, all shall be well.… Money pours in: salary check mysteriously gone up (Arvin’s work? for exams?). Our bank account from salaries mounts to $700, our poetry earnings since September shall soon touch $850 and auspiciously reach their set aim by June: we are going to try for poetry contests, jingle contests—trifling sums, but my gripping acquisitive sense thrives: I knew America would do this for us. Ted, yesterday, had two poems, “Of Cats” & “Relic,” accepted enthusiastically by Harper’s—not one rejection yet in the last three batches—pray that The Yale Review and The London Magazine will not be recalcitrant: strange what vicarious pleasure I get from Ted’s acceptances: pure sheer joy: almost as if he were holding the field open, keeping a foot in the door to the golden world, and thus keeping a place for me. Aim: to have my art poems—one to three (Gauguin, Klee and Rousseau)—completed by the end of March. I shall spend time in “the art library” at last. I feel my mind, my imagination, nudging, sprouting, prying and peering. The old anonymous millionairess seen this morning coming from the ugly boxed orangy stucco house next door, hobbling on one crutch down her path to the gleaming black limousine breathing oh-so-gently at the curb, burdened, bent, she, under the weight and bulk of a glossy mink coat, bending to get into the back of the car, as the rotund, rosy white-haired chauffeur held the door open for her. A bent mink-laden lady. And the mind runs, curious, into the crack in the door behind her: where does she come from, who is she? What loves and sorrows are strung on her rosary of hours? Ask the gardener, ask the cook, ask the maid: all the rough, useful retainers who keep a clockwork ritual of grace in a graceless house, barren-roomed and desolate.…

Saturday night, March 8. One of those nights when I wonder if I am alive, or have been ever. The noise of the cars on the pike is like a bad fever: Ted sickish, flagging in discontent: “I want to get clear of this life: trapped.” I think: Will we be less trapped in Boston? I dislike apartments, suburbs. I want to walk directly out my front door onto earth and into air free from exhaust. And I: what am I but a glorified automaton hearing myself, through a vast space of weariness, speak from the shell speaking-trumpet that is my mouth the dead words about life, suffering, and deep knowledge and ritual sacrifice. What is it that teaching kills? The juice, the sap—the substance of revelation: by making even the insoluble questions and multiple possible answers take on the granite assured stance of dogma. It does not kill this quick of life in students who come, each year, fresh, quick, to be awakened and pass on—but it kills the quick in me by forcing to formula the great visions, the great collocations and cadences of words and meanings. The good teacher, the proper teacher, must be ever-living in faith and ever-renewed in creative energy to keep the sap packed in herself, himself, as well as the work. I do not have the energy, or will to use the energy I have, and it would take all, to keep this flame alive. I am living and teaching on rereadings, on notes of other people, sour as heartburn, between two unachieved shapes: between the original teacher and the original writer: neither. And America wears me, wearies me. I am sick of the Cape, sick of Wellesley: all America seems one line of cars, moving, with people jammed in them, from one gas station to one diner and on. I must periodically refresh myself in this crass, crude, energetic, demanding and competitive new-country bath, but I am, in my deep soul, happiest on the moors—my deepest soul-scape, in the hills by the Spanish Mediterranean, in the old, history-crusted and still gracious, spacious cities: Paris, Rome.

… I can see chinks of light: of a new life. Will there be pain? The birth-giving pain is not yet known. Last night, weary, up the odd Gothic blind stairwell to Arvin’s for drinks: Fisher and the Gibians: dull, desultory talk about aborigines and me going out on the incoming of politics. Arvin: bald head pink, eyes and mouth dry slits as on some carved rubicund mask: a Baskin woodcut: huge, mammothed in the hall: a bulbous streaked head, stained, scarred, owl-eyed—“tormented man,” and a great, feathered, clawed fierce-eyed owl sitting in an intolerable eternal niche of air above the head.… I sense an acrid repulsion between the two men [Ted and Arvin]. I … see Arvin: dry, fingering his key ring compulsively in class, bright hard eyes red-rimmed, turned cruel, lecherous, hypnotic and holding me caught like the gnome Loerke held. Fisher, arms flapping, ridiculous, jumping up as if to urinate or be sick, only to leave, leaving his pipe, his drink half-finished. “He’s done that all year,” said the Gibians.

Monday night, March 10. Exhausted: is there ever a day otherwise. Alfred Kazin to dinner tonight: he: broken, somehow, embittered and unhappy: graying, his resonance diminished. Lovable still: and he and Ann, his wife, too a writer, another couple to speak to in this world. How babies complicate life: he paying also for a son. Ted is queerly sick still: how hopeless, helpless I feel with Ted pale, raggle-haired, miserable-visaged and there no clear malady, no clear remedy. He coughs, sweats, feels sick to his stomach. Pale and sweet and distant he looks.… I fall on the bed, drugged, with this queer sickish greeny-vinous fatigue. Drugged, gugged, stogged and sludged with weariness. My life is a discipline, a prison: I live for my own work, without which I am nothing. My writing. Nothing matters but Ted, Ted’s writing and my writing. Wise, he is, and I, too, growing wiser. We will remold, melt and remold our plans to give us better writing space. My nails are splitting and chipping. A bad sign. I suppose I really haven’t had a vacation all year: Thanksgiving a black-wept nightmare and Christmas the low blow of pneumonia and since then a struggle to keep health. Almost asleep in Newton’s class: must be up early, to laundry and to steal more pink pads of paper tomorrow. Kazin: at home with us, talking of reviews, his life: a second wife, blonde, and he being proud of her, touchingly. What is a life wherein one dreams of Fisher, furtive, in pink and gaudy purple and green houses, and Dunn and racks and racks of dresses?

Tuesday afternoon, March 11.… A thin green-yellow wash of light underlying bare ground, bare trees, warmly luminous and promising. Oh how my own life shines, beckons, as if I were caught, revolving, on a wheel, locked in the steel-toothed jaws of my schedule. Well, since January I have been holding a dialogue with myself and girding myself to stand fast without running. Now I am at a saturation point: fed up. The thought of outlining three hours of Strindberg plays this week appalls me. While Strindberg should be most fun of all. I turn to these pages as toward a cool fluid drink of water—as being closest to my life—words must sound, sing, mean. I hear a tin cup chink on a fountain brim as I say “drink.” I must grow ingrown, queer, simply from indwelling and playing true to my own gnomes and demons.… Today, overslept caught in some gross and oppressive nightmare involving maps and pale sandy deserts and people in cars—a sense of guilt, bad-faith, embarrassment and sallow sulphurous misery brooding over all, listened to the same Arvin lecture on Mardi I heard four years ago and a lecture on the pure abstractionist Mondrian: as warm as Platonic linoleum squares.

Thursday morning, March 13.… I sit, warm, drowsy and at the other side of the shakes, writing here, trying to build up a calm center. Yesterday was a horror—Ted said something about the moon and Saturn to explain the curse which strung me tight as a wire and twanged unmercifully. Too tired for the saving humor, downed, doused in my vital quick.… Quarrel with Ted over sewing on buttons on jackets (which I must do), wearing his gray suit, and such trivia, he getting up from sickness, me going down into it. Gulping a chicken wing and a mess of spinach and bacon, all, all, turning to poison. Dream Play—ambitious production—the daughter dancing descent through a scrim of clouds, her voice stiff and stagy … the irony of the play being that it is all true in my own life. We had just finished quarreling about buttons and haircuts (like their salads and such as a basis for divorce), and especially the repetition of schooling the officer goes through—teaching and learning forever that twice two is … what? And I, sitting too in the same seat I occupied three, four, five, six, seven years ago, teaching what I learned one, two, three, four years ago, with less vigor than I studied and learned—living among ghosts and familiar faces I pretend not to recognize.… All rolling over on itself, tasting of sourdough, tasting of heartburn. Now I must leap into my clothes and stride to class, early, to steal three pink books: yes, for my novel: have just read the sensationalist trash which is Nightwoodl —all perverts, all ranting, melodramatic: “The sex God forgot.”—self-pity, like the stage whine of the Dream Play. Pity us: Oh, Oh, Oh: Mankind is pitiable.…

Friday afternoon, March 14.… Deep sleep last night and queer nightmares—fragmented rememberings at breakfast: of Newton Arvin: withered, mysterious, villainous, shrunken heads to piece together, clues to deceptions: heads lollipop size, withered, painted ruddy over the shrunk corruption of approaching death. Dark elevations of floors and stairs in unlit libraries. Pursuit, guilt.… I am yet in a dream, unproductive, weary. Got a notice from the Guggenheim people and the Houghton Mifflin awards—hopeless to concern myself about until I have written my two books by the end of next year. Ted getting a phone call this afternoon from blessed paternal white-haired Jack Sweeney asking Ted to read at Harvard on the Morris Gray readership on Friday April 11th for the princely sum of $100 and expenses! One hour of his own poems: to us this looks like professional glory. Greasy dishes pile up in the kitchen, the garbage can overflows with coffee grounds, rancid fat, rotting fruit rinds and vegetable scrapings: a world of stinks, blemishes, idle dreams, fatigue and sickness: to death. I feel like a dead person offered the fruits and riches and joys of the world only if she will get up and walk. Will my legs be sturdy? My trial period approaches. To bed now and resolutely to work tomorrow. Save, conserve: wisdom, knowledge, smells and insights for the page: to wrestle through slick shellacked facades to the real shapes and smells and meanings behind the masks.

In the past two days, Sunday and Monday, Ted and I have had, respectively, dinner and tea (and lecture) with two American “poets.” Queerness of queernesses. Ben Hurley and Ralph Rogers. Sunday afternoon we drove across the wide flat ice-gray Connecticut River and into the snow-covered Holyoke range with its bristles of bare winter trees and up into the ugly black-smeared brick atrocities of Victorian Holyoke. Raoul lives in a faculty house facing out over white snowfields into the purpling and bristled hills. We shouldered into his tiny room with its cot and, surprisingly, real fireplace with a log burning red. Walls covered with odd and tawdry papers: the sheet of an old piece of music, a print in color of an ancient French unicorn tapestry, theater bills; two women teachers: a young, soft dark-haired girl in a cover-up dress of electric blue: Joyce someone, who teaches modern philosophy and lisps somewhat, slightly bucktoothed. And Miss Mount, a fat dowdy fixed lady, with gray hair that looked as if it needed dusting, an ugly, or, rather, nondescript suit and layers of spreckled fat skin. She proceeded, over sherry and a nut or two from a glass jar which Raoul passed around, to relate the story of Dylan Thomas’s visit to Holyoke in raucous, shrill tones which allowed of no interruptions: a woman who never listens, a horrible woman, shaped in hard round bullet shapes, squat, unsympathetic as a dry toad. Dirty decaying teeth, hands with that worn glisten of flesh unmarried old ladies have: a glitter of rhinestones somewhere, a pin, or chain. We talked of nothing: the Dylan Thomas story lasted till dinnertime and Joyce, bearing a platter of white cut bread covered with a gray-pink pâté specked with something black, led us down the ugly brown stairs to an uncomfortable private dining room, a too-varnished, too-polished mahogany table and skittery stiff-backed chairs. I drank quickly and never modestly demurred when Raoul came round with the red wine. An ugly fattish yellow dolt-faced girl with purplish acne waited on us. I sat on Raoul’s left, facing the irrepressible Miss Mount, who evidently had taken an immediate dislike to me and whom I proceeded to ignore. “Ben’s here,” Joyce softly and joyously exclaimed. And my first impression was: he’s a madman. He gave the impression of being too brightly colored blue and yellow, and ravaged by years of sandblasting. Goggle, electric-blue frog eyes, a pocked, vivid tan coarse-pored skin, short blondish hair, and a pale sleazy whitish-cream jacket that didn’t hang right and gave him a cockeyed, humpbacked look. Heavy black leather ski-type boots, or perhaps, hiking boots, and, again, pants that hung as on bandy legs. He began to talk immediately in a rather high, grating voice: frank, fanatic and open. I spent the mealtime talking with him, raising my voice, too: everybody giggled, gulped wine (except Miss Mount) and raised their voices. I began to go pleasantly erotic, feeling my body compact and sinewy, feeling like seducing a hundred men. But immediately, I turn to Ted: all I have to do is think of that first night I saw him, and that’s it. Hurley raved: politics, Ezra Pound: we agreed a man was all of a piece, couldn’t really compartmentalize himself, airtight. Hurley (winner of at least two Guggenheims) raved against the giving of Guggenheims to old safe famous people and advocated their bestowal on poets who spent the money on women and drink and were politically radical. We all flowed upstairs again, Hurley having, in the course of the meal (thick slabs of roast beef, watery string beans, roast potato and some ghastly ice cream, vanilla rounds with a green shamrock of mint-flavored ice cream in the middle), put on greenish-hued sunglasses. Hurley promptly pulled down the blinds of the window, all except one long thin strip of window, and cut out the snow-blinding view: the left strip showed stark and delicately-colored, like a Japanese watercolor—lavender mountains, white plains of snow, and a stipple of bushes, grasses and trees perfect as lines of a calligraph. We drank black, bitter espresso coffee which Antoine made in a queer chromium-tubed pot, and then brandy. Antoine passed a glass jar of pink, green, yellow and lavender Easter-egg candies. We left then. Hurley shaking hands good-bye and miraculously leaving my hand full of a bunch of his pamphlets on poetry and politics, his “Americana.”

Thursday morning, March 20.… I give myself a week—through next Wednesday: and give up the idea of the long contest. Have narrowed down poem subjects to Klee (five paintings and etchings) and Rousseau (two paintings) and will try, arbitrarily, one a day. Each subject appeals, deeply, to me. Must drop them in my mind and let them grow rich, encrusted. And choose: choose one today. I sit in a stupor—torn, torn: a pure whole week, and me so far from my deep self, from the demon within, that I sit giddy on a painted surface. Yesterday: sat in the art libe soaking and seeping in pictures. I think I will try to buy the Paul Klee book. Or at least, get it over the weekend. Reminders now, of the sea wrack of the past week: the most sickening, the most embarrassing of experiences: Monday—tea with Ralph Rogers at the Roches’ and a horror of a lecture in the Browsing Room. Paul, with his professional dewy blue-eyed look and his commercially gilded and curled blond hair on his erect, dainty-bored aristocrat head looking as if it had been struck on a Greek coin that since had blurred and thinned from too much public barter and fingering. “One of the finest minor poets in America,” Paul breathed over the phone. Rogers sickened Ted and me the minute he walked into Paul’s living room with his slick nervous smile, his jittery huckster hand jingling money in his pants pocket. Clarissa, apparently recently recovered from a sulk of tears, slouched about in a baggy white sweatshirt and a blue and white full skirt, and baby-buttoned ballet shoes, like Miss Muffet in a private tantrum. And the lecture: I writhed, bristled. In that dark-wooded and antique room with its dim light and worn, deep, comfortable chairs and darkened Oriental rugs, with the hollow-coffined grandfather clock ticking its sepulchral ticks and the oil portrait of Mary Ellen Chase leaning forward, as if out of the gilt restraining frame, her white hair an aureole, a luminous nimbus. Rogers garbled his bible of crudities to the literary Mademoiselle Defarges of Smith, knitting his slick and commercial words into cable-stitched sweaters and multi-colored argyles. Intolerable: catchpenny phrases. “This is the point, do you get it, I’ll just tie this up.” Ralph Rogers, it develops, has a handy little storage closet (personal, private) called the “subconscious” or, more glibly, the “subliminal,” where he tosses all his old dreams, his ideas and visions. Buzz, snip, handy little demons get to work, and presto! a few hours, days or months later he writes out a poem—zip-zip. What’s it mean? I dunno—You tell me. He reads some of his own trash: a jeweled dog and a boy licking a sticky lollypop. What’s it mean? A poem’s gotta move—He gets boys in academy to write him interpretations of his own poems: “fabulous!” He tosses a sheaf of paper on the table, waves a poem about the animal, March, with its “pussy-willow eyes” in “the latest issue of The Atlantic.” Brags: “I’ve just sold this to Poetry London-New York.” The more interpretations a poem has, the better a poem it is. Why, anyone can write: He even wrote a poem in twenty minutes on stage for a show called “Creation While You Watch”—one guy improvised mood music, another painted while Ralph Rogers fished up a mood poem in his unconscious and wrote it on the blackboard—that’s pressure-cooker poetry.

Friday afternoon, March 28. A whole week, and I haven’t written here, nor picked up the book. For good reason. For the first time a lapse of writing here spells writing. I was taken by a frenzy a week ago Thursday, my first real day of vacation, and the frenzy has continued ever since: writing and writing: I wrote eight poems in the last eight days, long poems, lyrical poems, and thunderous poems: poems breaking open my real experience of life in the last five years: life which has been shut up, untouchable, in a rococo crystal cage, not to be touched. I feel these are the best poems I have ever done. Occasionally I lifted my head, ached, felt exhausted. Saturday I groaned, took pellets of Bufferin, stitched in the worst cramps and faintness for months, which no pills dulled, and wrote nothing: that night we went to a dull dinner at the Roches’ with Dorothy Wrinch, who acted like a gray-haired idiot, goggling, going through her little-gray-haired-misunderstood-genius-scientist act. She obviously does not care for Ted: he is too honest and simple and strong and un-Oxford and untwittery for her. She obviously was miffed I said I’d call her for coffee and never did: but I won’t either. I don’t care a damn for her and won’t waste poem-time on people I can’t stand. One night, late, we walked out and saw the lurid orange glow of a fire down below the high school. I dragged Ted to it, hoping for houses in a holocaust, parents jumping out of the window with babies, but nothing such: a neighborhood burning a communal acreage of scrubby grass field, flames orange in darkness, friendly shouts across the flaming wasteland, silhouettes of men and children fixing a border with tufts of lit grasses, beating out a blaze with brooms as it jeopardized a fence. We walked round, and stood where a householder stood grimly and doggedly wetting his chrysanthemum stalks and letting the waters run into a little dyke or ditch, separating his patch of lawn from the crackling red-lit weed stalks. The fire was oddly satisfying. I longed for an incident, an accident. What unleashed desire there must be in one for general carnage. I walk around the streets, braced and ready and almost wishing to test my eye and fiber on tragedy—a child crushed by a car, a house on fire, someone thrown into a tree by a horse. Nothing happens: I walk the razor’s edge of jeopardy.…

This work, teaching, has done me much good: I can tell from the way my poems spouted this last week: a broad wide voice thunders and sings of joy, sorrow and the deep visions of queer and terrible and exotic worlds.…

We want to buy art books. De Chirico. Paul Klee. I have written two poems on paintings by De Chirico which seize my imagination—“The Disquieting Muses” and “On the Decline of Oracles” (after his early painting, The Enigma of the Oracle) and two on paintings by Rousseau—a green and moony mood-piece, “Snakecharmer,” and my last poem of the eight, as I’ve said, a sestina on Yadwigha, “The Dream.”m

I shall copy here some quotations from a translated prose poem by De Chirico, or from his diaries, which have unique power to move me, one of which, the first, is the epigraph to my poem “On the Decline of Oracles”:

1) “Inside a ruined temple the broken statue of a god spoke a mysterious language.”

2) “Ferrara: The old ghetto where one could find candy and cookies in exceedingly strange and metaphysical shapes.”

3) “Day is breaking. This is the hour of the enigma. This is also the hour of prehistory. The fancied song, the revelatory song of the last, morning dream of the prophet asleep at the foot of the sacred column, near the cold, white simulacrum of god.”

4) “What shall I love unless it be The Enigma?”

And everywhere in Chirico city, the trapped train puffing its cloud in a labyrinth of heavy arches, vaults, arcades. The statue, recumbent, of Ariadne, deserted, asleep, in the center of empty, mysteriously shadowed squares. And the long shadows cast by unseen figures—human or of stone it is impossible to tell. Ted is right, infallibly, when he criticizes my poems and suggests, here, there, the right word—“marvelingly” instead of “admiringly,” and so on. Arrogrant, I think I have written lines which qualify me to be The Poetess of America (as Ted will be The Poet of England and her dominions). Who rivals? Well, in history Sappho, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Christina Rossetti, Amy Lowell, Emily Dickinson, Edna St. Vincent Millay—all dead. Now: Edith Sitwell and Marianne Moore, the aging giantesses, and poetic godmother Phyllis McGinley is out—light verse: she’s sold herself. Rather: May Swenson, Isabella Gardner, and most close, Adrienne Cecile Rich—who will soon be eclipsed by these eight poems: I am eager, chafing, sure of my gift, wanting only to train and teach it—I’ll count the magazines and money I break open by these best eight poems from now on. We’ll see.…

… Sore. Grumpy with Ted, who sometimes strikes my finicky nerves [omission]…. And I am much worse—petulant, procrastinating, chafing with ill will at the inevitable grind beginning again.