(left to right) David Lloyd Owen, Jake Easonsmith and Gus Holliman, three LRDG officers sporting a variety of headwear. Only Lloyd Owen survived the war. (Author’s Collection)

CHAPTER 7

MISUSE AND MALARIA

May had been a trying month for the LRDG, as it had been for the Allied army as a whole. On 27 May three Afrika Korps assault groups had driven the British out of the Halfaya Pass, the strategically important escarpment just inside the Egyptian border with Libya. The enemy, noted General Rommel, ‘fled in panic to the east, leaving considerable booty and material of all kinds in our hands’.1 The next day, 28 May, a gloomy General Wavell lamented the fact that his ‘infantry tanks are really too slow for a battle in the desert’. Easy prey for the German 88mm anti-tank guns, the British armoured corps had suffered heavy casualties since the arrival of the Afrika Korps, but Wavell nonetheless retained his belief that he would ‘succeed in driving the enemy west of Tobruk’.

(left to right) David Lloyd Owen, Jake Easonsmith and Gus Holliman, three LRDG officers sporting a variety of headwear. Only Lloyd Owen survived the war. (Author’s Collection)

As Wavell prepared to launch Operation Battleaxe in mid-June, he received a complaint from Ralph Bagnold ‘as to the misuse of the LRDG Patrols’ in the preceding weeks. Teddy Mitford in particular had agitated for a more ‘active employment’ rather than acting as garrison troops and fetching and carrying supplies to Mersa Matruh. Additionally, an outbreak of sickness at Siwa had decimated G patrol. ‘Men started going down with a fever which the medical officer attached to the squadron diagnosed as malaria,’ recorded Crichton-Stuart. ‘When he sent to Mersa Matruh for supplies of quinine and other appropriate medicines he got the curatives he asked for, but the authorities refused to send him the necessary preventatives, curtly informing him that Siwa was NOT [they repeated NOT] malarial.’2 Eventually an expert in tropical diseases was despatched to Siwa from Cairo and within 24 hours he confirmed that ‘the oasis was swarming with anopheles mosquitoes’.

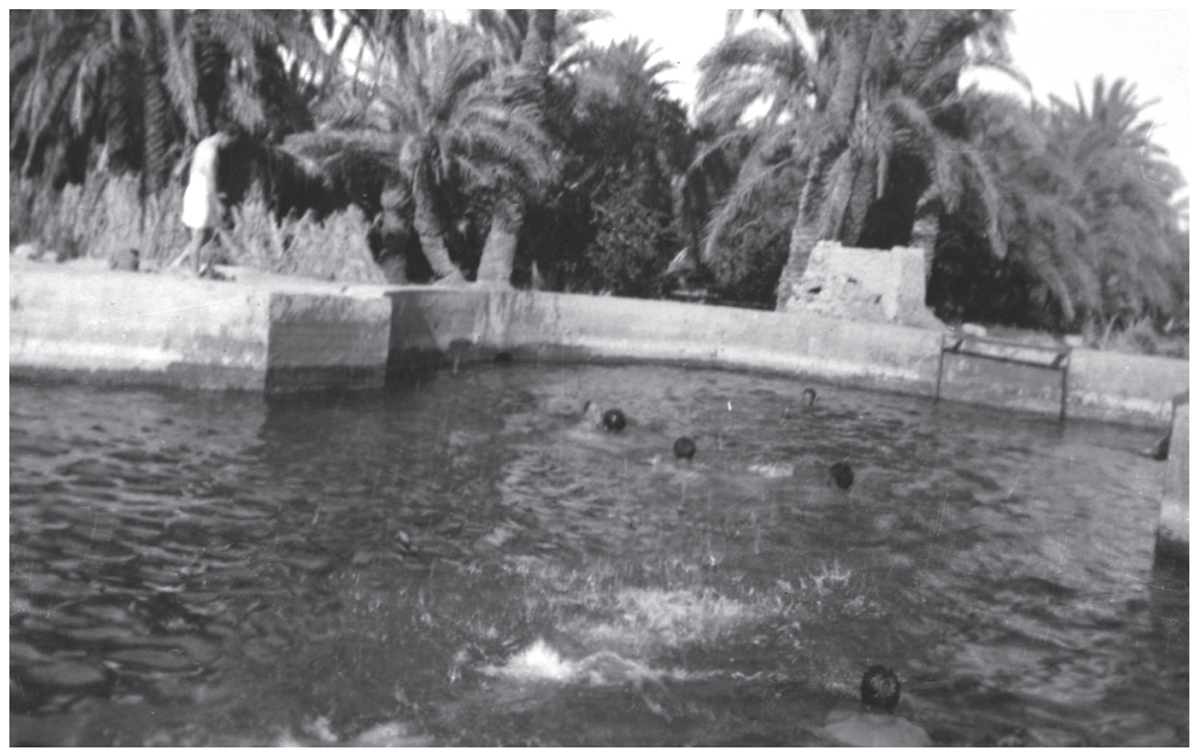

THE IRRIGATION POOLS AT SIWA

The irrigation pools at Siwa were the perfect way to cool off at the end of a long patrol, or even a long day. (Courtesy of the SAS Regimental Archive)

There were many of the pools at Siwa and while some were used solely for bathing, others were reserved for washing laundry. (Courtesy of the SAS Regimental Archive)

Captain Michael Crichton-Stuart recalled: ‘Out of their dark green depths cool water bubbled … they made the midsummer heat of Siwa easy to bear.’ (Courtesy of the SAS Regimental Archive)

On 6 June Captain Pat McCraith rejoined the LRDG at Siwa, arriving from Cairo with a batch of new trucks to replace the ones lost in recent patrols. The following day Y Patrol returned from Jarabub and the unit underwent another reorganization: Y, G and a new temporary patrol, H, were formed, with McCraith leading Y, Crichton-Stuart G and Jake Easonsmith H. All three patrols comprised six trucks and were issued with similar instructions, ‘the conveyance of agents to the interior of Cyrenaica and the collection of their reports, and with gathering geographical information about the country south of the Jebel-el-Akhdar’.3 Also formed in June 1941 was the unit’s Survey Section, under the eye of Bill Kennedy Shaw.

The exploits of the LRDG captured the media’s imagination and they appeared in newspapers, magazines and even gave radio interviews during the desert campaign. (Getty)

The day before Crichton-Stuart was scheduled to lead his patrol on a surveillance of enemy traffic on the main road through the lush countryside of the Jebel Akhdar, he succumbed to malaria. Reluctantly he handed over command to Jake Easonsmith, of Y Patrol, who took with him a recently arrived G Patrol officer called Anthony Hay, erstwhile of the Coldstream Guards. Hay was to replace Crichton-Stuart, who had been summoned back to the Scots Guards, and although he had persuaded his CO to allow him three months to school Hay in the work of an LRDG officer, Crichton-Stuart’s remaining time in the unit was bedevilled by recurrent malaria. Throughout the summer he spent a lot of time in Mersa Matruh, grouching at the misuse of the LRDG and of another special forces unit called Layforce. Formed in the summer of 1940, just as the LRDG came into being, Layforce was commanded by Colonel Robert Laycock and comprised three commando troops – Nos. 7, 8 and 11. No. 8 Commando was also known as Guards Commando, and among its ranks when it sailed from Britain on the last day of January 1941 were Randolph Churchill, the prime minister’s son, George Jellicoe, son of the famous World War I admiral, and a 25-year-old Scots Guards lieutenant called David Stirling. Crichton-Stuart wrote:

The frustration felt by the LRDG during this season was shared and even exceeded by a commando force under Colonel Laycock … They spent the summer in abortive attempts at harassing the enemy’s rear by sea landings. At the end of the summer the force was disbanded, defeated by the difficulties of a rocky coast and the unreliable sea. It was simply not yet realised that the desert approach was incomparably easier and safer, for there you could hide from the air.4

Most of Layforce were returned to their parent units, but not David Stirling. Crichton-Stuart met him several times in Cairo and Mersa Matruh and the former was keen to pump the LRDG officer for information on their operations. Together the pair ‘discussed … at length’ the advantages of a desert approach to enemy targets rather than a seaborne approach. Crichton-Stuart, of course, was thinking solely of using vehicles. Stirling, however, had another method in mind, one that in the course of that summer started to take shape.