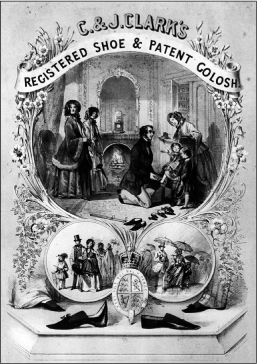

This aspirational 1851 showcard for goloshes features a suave salesman complete with foot-measuring gauge. Sadly, goloshes turned out to be an unsuccessful venture.

So many items in the balance sheet turned out to be worthless, and there was so much confusion in the way the capital accounts had been entered in the ledger that even after the decision to struggle on had been taken it was found that things were worse than had been supposed.

THAT WAS THE BLUNT ASSESSMENT of William S. Clark, James’s son, writing in 1914 while reflecting on the period leading to the firm’s second financial crisis in 1863, a catastrophe that would have proved fatal without the help, once again, of Quaker friends and cousins.

Business had picked up after the 1851 Great Exhibition and continued on an upward curve almost until 1859. These were the golden years of Cyrus’s and James’s stewardship of the company – albeit a stewardship that was largely overseen by outside investors and by the bank. In 1857, C. & J. Clark produced 234,000 pairs of shoes – far exceeding Cyrus’s expectations back in 1840 when he said the company would be able to sell a maximum of 9,000 pairs in any twelve months. Turnover from 1851 to 1859 was on average five times what it had been in 1833, with shoes now representing three-quarters of sales. The average annual profit during that period was £2,683, compared with £1,230 during the years from 1843 to 1847. There was a doubling of sales between 1849 and 1858, spurred by demand for ready-made footwear, which was widely regarded as both modern and better value than bespoke. Business was also helped by the country’s recovery from economic depression and the beginnings of the age of ‘Victorian Prosperity’.

There were some false starts, one of which was the production of so-called ‘elongating goloshes’, for which C. & J. Clark had been awarded a Gold Medal at the Great Exhibition. Goloshes (the spelling changed to galoshes during the 1920s) were made from gutta percha, a natural latex produced from the sap of the tree of the same name. They were introduced to Britain in 1844 and greeted enthusiastically by manufacturers up and down the land. An encyclopaedia from the time said:

The immediate effect of its discovery may be compared with that of the gold fields in California and Australia; and perhaps no commodity, except the precious metals, has been more eagerly sought after or more highly appreciated.

Cyrus and James were acutely interested in this ‘discovery’ because the price of leather was forever fluctuating and, moreover, it was becoming hard to achieve a uniform standard in leather. The quality of the hides was inconsistent and the leather sorters and cutters varied in their expertise. C. & J. Clark was selling a number of gutta percha products as early as 1848, prompting James to take out a patent on boots, shoes and clogs made with this new material, and such was the focus on gutta percha that in the 1851 census two employees of the company described themselves as ‘gutta percha workers’ rather than shoemakers.

But the elongated golosh – which could be put on without the need to stoop and with no straps to fasten – proved unsuccessful commercially as cheaper options flooded the market. And they never quite did technically what they were billed to do. Consequently, at one point in 1855, Clarks opened a dedicated store in London’s Blackfriars Road on a three-month lease in order to shift surplus stock of goloshes by means of a closing-down sale.

The partners accepted that goloshes had become ‘very heavy losers arising entirely from a fault in the gutta percha which after a few years became so hard and brittle that it will stand no wear,’ and by 1858 the company’s price list featured no gutta percha footwear of any kind.

This aspirational 1851 showcard for goloshes features a suave salesman complete with foot-measuring gauge. Sadly, goloshes turned out to be an unsuccessful venture.

It was a similar story with vulcanised rubber – named after Vulcan, the Roman god of fire – when the company bought a half share in a patent for combining leather and rubber to produce an elastic material that did away with the need for buttons or laces. Between 1851 and the spring of 1855, C. & J. Clark acquired a massive £25,000 worth of vulcanised rubber – but to little financial benefit.

During this experimental phase, Charles Goodyear, the American whose name would later be associated with tyres, had become a friend of Cyrus and James and gave advice about the production of a new rubberised boot. Goodyear, who said there was no other ‘inert substance which so excites the mind’ as rubber, was a year older than Cyrus and had begun his own business career by opening a hardware store in Philadelphia. Cyrus and Charles would have met at the Great Exhibition when the American’s wares were on display in a huge pavilion built from floor to ceiling entirely of rubber. Goodyear never opened a factory in Britain, but a company in France agreed to manufacture vulcanised rubber – with disastrous results, ending up with Goodyear being arrested by the French police in December 1855 and spending sixteen days in a debtors’ prison.

Five years later, Goodyear was dead, leaving debts of $200,000, but he went to his grave firm in the belief that his invention would eventually pay off. And so it did, though not for his immediate descendants. None of his family, either at that time or in subsequent years, was involved in The Goodyear Tyre & Rubber Company, which was so named in Charles’s honour. Despite his turbulent career, Goodyear, quoted in the January 1958 American edition of Reader’s Digest, was philosopical:

Life should not be estimated exclusively by the standard of dollars and cents. I am not disposed to complain that I have planted and others have gathered the fruits. A man has cause for regret only when he sows and no one reaps.

The Clarks also investigated doing business with the North British Rubber Company, which had been set up by Henry Lee Norris, an entrepreneur from New Jersey, and Spencer Thomas Parmalee from Connecticut, who had moved to Edinburgh in 1856. The unreliable quality of Norris’s and Parmalee’s vulcanised rubber ultimately put an end to any formal business arrangement, but the partners had showed once again their readiness to explore new shoemaking techniques.

![]()

William S. Clark joined the company in January 1855 at the age of sixteen. He had been educated at two Quaker schools, Sidcot, in Winscombe, and Bootham, in York, and spent some months studying chemistry at the Laboratory of St Thomas’s Hospital in London under the tutelage of a Dr Thompson. His arrival in the business coincided with the first attempts at introducing machinery into the manufacturing process.

William was determined to be a modern shoemaker. Which is to say that he regarded technology as the way forward – and he wanted to see an end to the outworker system. In effect, he wanted shoemaking in Britain to catch up with what was going on in America, where, because of a shortage of labour, the search for machinery to replace men had quickened. The earliest footwear machines to have been patented in the US are thought to be David Mead Randolph’s invention for making riveted boots in 1809, followed a year later by Marc Isambard Brunel’s invention for the nailing of army and navy shoes. But a far more revolutionary development was on its way, one which would bring about a surge in the ready-made market and create havoc for the bespoke trade: the sewing machine.

Cyrus and James may have been resistant to some aspects of modern business practice – and, as William pointed out, their accounting methods were lamentable – but shunning innovation was never something of which they could be accused.

C. & J. Clark’s machine room began to take shape in 1856 when Singer & Co., based in America, persuaded the Clarks to acquire one of their sewing machines on trial. Isaac Singer, a failed actor and farmer, had patented his creation in New York in partnership with Edward Clark (no relation to the Clarks of Street). Singer invented the first commercially successful sewing machine, and between 1851 and 1863 he took out twenty patents and sold his machines throughout the world. It was, however, the British inventor and cabinet maker, Thomas Saint, who had issued the first patent for a general machine for sewing in 1790 – though he may not actually have produced a working prototype. That patent describes an awl that punched a hole in leather and passed a needle through the hole.

The arrival of sewing machines had caused controversy. In 1834, Walter Hunt, an American, had built such a machine, but did not patent it because he thought it would cause unemployment. Ten years later, the first American patent was issued by Elias Howe for a ‘process that used thread from two different sources’. His machine had a needle with an eye at the point. The needle was pushed through the cloth and a loop was formed on the other side. A shuttle on a track then slipped the second thread through the loop to create what was, and still is, called the lockstitch – at five times the speed of a fast hand-sewer.

Howe assigned the British rights to his patent to a corset, umbrella and footwear manufacturer called William Thomas of London – and then sued Singer for patent infringement in 1854 and won. Howe saw his annual income jump from $300 to more than $200,000 a year, and he amassed a fortune of nearly $2 million over the next twenty years or so. During the American Civil War, he donated a portion of his wealth to equip an infantry regiment for the Union Army and served in the regiment himself as a private.

Singers, as they were known, were worked by treadle and were cumbersome beasts that required a dedicated person to master them. In Street, it was William S. Clark who spent three months learning every aspect of their capabilities, before passing on his knowledge to a trio of technically-minded women, all sharing the same forename – Mary Wallis, Mary Ann Haines and Mary Marsh. They quickly became experts themselves. The Clarks then bought two further Singer sewing machines for £30 each.

Output increased dramatically. By 1858, over 50,000 pairs of uppers were stitched by machine, accounting for 23 per cent of total production. And by now there were more women in the machine room than there had been in the whole factory five years earlier.

At the same time, riveting was becoming commonplace, and C. & J. Clark was one of the first firms to sell hand-riveted shoes on a large scale. Riveting was especially good for thick-soled boots or shoes.

Sewing machines and riveting spawned new machinery at C. & J. Clark for many of the ancillary jobs previously carried out by hand. For example, in 1858, Samuel Boyce, a boot manufacturer in Lynn, Massachusetts – and a friend of James Clark – produced a device that cut soles to size. It was worked by a foot treadle and became one of the first machines imported from America for use in the British shoe trade.

An enterprising man called James Miles, of Street, took it upon himself to copy or adapt these American machines, selling them on to shoemakers up and down the country. Likewise, William S. Clark and John Keats, the factory foreman (who claimed to be related to the poet of the same name), jointly invented a machine for the building up and the attaching of heels to soles, mainly of boots. This involved enlarging the heels in solid iron moulds and then punching holes in them, into which rivets were inserted before being attached to the boots. There was considerable secrecy over this piece of equipment, for fear that rival firms in Northamptonshire and Leicestershire would hear about it.

Not everyone was happy. The introduction of technology led to strikes in some traditional shoemaking towns in the Midlands, but the Clarks persuaded their workforce that technology would lead to more, not fewer, jobs, and largely avoided disruptive labour unrest organised by what were known as ‘craft societies’ – a precursor to the trade unions.

Encouraged by William, Cyrus and James also turned their attention to lasts, acquiring equipment in 1855 that would ‘secure good fitting boots and shoes … made from the finest wood seasoned on the premises’, as they described it on a price list sent out to customers that year. Their first last-making machine was bought from a Scottish supplier for £12. 10s., with a condition of sale that a man called David Garner would move to Street to be in charge of it. Garner was paid 33 shillings a week, but there were stipulations attached to his employment. He had to give up alcohol and attend church.

How long Garner survived in his job is unclear, but his machine was soon replaced by one that would, according to company records, ‘turn a right or a left last from the same pattern, or a large or small last from the same pattern’. These were state-of-the-art creations because a large proportion of footwear, particularly in children’s ranges, was still made without any distinction between right and left feet.

By 1855, the shoe business in Street was improving faster than the quality of life. The town’s poor drainage and inadequate water supply had been highlighted in official reports. One review conducted by the Board of Health in 1853 – a year after a typhoid epidemic struck the southwest of the country – noted with alarm that the only form of drainage was an open stream running through the main street, into which almost all houses discharged their waste. It was persistently stagnant and smelt dreadful.

There were a number of deaths from typhoid, including that of Cyrus’s son, Joseph Henry, who died aged nineteen, and James’s second son, Thomas Bryant, who was only nine. James reacted bravely, describing his loss as a ‘bitter trial’, but one that ‘was sent in mercy by our Heavenly Father to bring us nearer to Himself. None but those who have experienced it can know of the bitterness of such a trial’.

In its report, the Board of Health took a sterner, more pragmatic view:

There is no public provision of water within the parish, the inhabitants mostly obtaining their water from wells, the water of which is generally of an extremely hard quality, and sometimes polluted by a leakage from cesspools.

The Board’s report went on to cite the Public Health Act of 1848 and insisted on the setting up of a Local Board, comprising nine elected members, whose purpose was to monitor the sanitary conditions in the town.

In addition to typhoid, Street suffered from other diseases such as scarlet fever and measles. As Michael McGarvie described it in Bowlingreen Mill:

Various causes were suggested for this including that the orchards with which Street was surrounded impeded the circulation of the air and so increased the dampness, or that the out-work system under which six to nine men worked together in a small room was conducive to illness. The real culprit was defective drainage and the pollution of the stream which ran along the High Street. C. & J. Clark’s factory contributed substantially to this.

Blame was indeed laid at C. & J. Clark’s door. The Board of Health’s report found that the:

… refuse drainage and tan liquid of the [Clarks] factory is passed into the stream towards the lower end. The condition of the stream and of the various ditches is at times very offensive.

James Clark was quoted in the Report admitting that:

… the drainage liquor consists of the boilings of dye-wood, alum and muriatic acid … liquor in which green skins have been soaked, and whether from the presence of animal matter in a state of decomposition, or of vegetable matter in a similar state, has a very offensive smell.

Feelings were running high. Cyrus chaired a meeting in 1852 at the Temperance Hall to explain to ratepayers the implications of the Board of Health’s report, opening proceedings with a diplomatic aside that ‘good temper always gained the advantage in argument’. Some pointed an accusing finger at the Clarks, prompting James, seated near his brother, to remind people of ‘the deaths and illness in our own families’. The meeting ended more harmoniously than it had started.

James became a more active and devoted Quaker following the death of his son. At the family’s morning meetings – which he insisted on, with no exceptions – he began praying out loud in front of his surviving children and would, as he put it, ‘express a few words in the evening meeting’ as well. This, James said, ‘proved very formidable’, but he was rewarded with a sense of:

… peace, which I believe always follows an act of obedience to our Heavenly Father. From this time I had frequently some brief communications to offer in our meetings for worship.

In 1856, four years after this personal tragedy, James was appointed a minister in the Society of Friends, something which ‘led me more deeply to feel my responsibility and strengthening me by this proof that I had the confidence of my friends’. In the spring of 1860 – the year his eldest daughter, Mary, became engaged to John Morland, who later would take over the rug side of the business – he felt enormous pride when his wife was appointed an elder of the Street Friends’ meeting house:

A very precious, wise and useful Elder she proved to be … no one can know how much I have been indebted to her for her wise, loving and faithful counsel.

![]()

Towards the end of 1853, Britain established formal ties with Turkey, which was at war with Russia. Lord Aberdeen, the prime minister in charge of a coalition government, described the ‘state of tension’ in the Crimea as ‘undoubtedly great’ but said: ‘I persist in thinking that it can not end in actual war’. The Times went further, thundering that ‘War would not only be an act of insanity, but would be utterly disgraceful to all of us concerned.’

But there was no sign of Russia backing down. Instead, its navy sank the Turkish fleet at Sinope, provoking a declaration of war by Britain and France on 28 March 1854. The resulting campaign in the Crimea was to be a war like none before it. For the first time, photography brought home the graphic horrors of battle and there were stories in the press as much about inefficiency and incompetence as tales of heroism and bravery. The work of Florence Nightingale ensured that the war pulled at the conscience of those not immediately caught up in the conflict, especially when it became evident that more soldiers were dying from disease than from fighting the enemy.

In Street, the Crimean War tugged at the conscience in a different way. Quakers were pacifists. They were duty bound not to interfere in the war effort – but they also felt called to alleviate the suffering of war’s innocent victims. As William S. Clark wrote:

The Government urgently wanted a supply of sheepskin wool coats to save troops in the Crimea from perishing with cold. As C. & J. Clark had a supply of skins that were suitable for this and that could not be got elsewhere in sufficient quantity they felt bound to make these coats but decided not to keep any profit for their own use.

That profit came to some £300 – a large sum at the time – all of which was used to build the British School in Street. Education was important to Quakers. George Fox himself had established two schools, one at Waltham Abbey, Essex, another at Shacklewell, in what is now part of the London Borough of Hackney. Fox said these institutions were to ‘instruct young lasses and maidens in whatsoever things were civil and useful in the creation’.

The Western Gazette, a local newspaper covering Somerset and the West Country, picked up on the story of Clarks making coats for soldiers fighting the Russians but failed to inform readers of the not-for-profit motive:

Our enterprising manufacturer, Messrs Clarke [sic] of this place, are preparing at the rate of 40 sheepskin coats a day for the army in the Crimea. The sheepskins are prepared with all the wool on and are intended to be worn by our men in just the opposite way that they are worn in general – the wool will be worn inside and the skin outside.

Elmhurst, the house that Cyrus Clark built for himself in 1856, photographed in 1860 by his eldest son John Aubrey Clark. In the foreground can be seen (left to right) Cyrus’s daughter Bessie (Sarah Elizabeth), his wife Sarah Bull Clark, Cyrus, and (at far right) his youngest son Thomas Beaven Clark.

As the Crimean War reached the bloodiest of conclusions, C. & J. Clark was fighting its own battles. Heavy losses were incurred between 1859 and 1862, for which a number of reasons were cited, not least the manner in which Cyrus and James continued to take money out of the business for their own benefit. In 1856, Cyrus had built an entirely new house, Elmhurst, which a few years later he would use as security for further loans to the business. James, meanwhile, made such alterations and additions to Netherleigh that it almost doubled in size. This may have been a practical necessity because he and Eleanor had such a large family – but it did not help balance the books. At the same time, Cyrus agreed to build a house for the second of his three sons, Alfred, to mark his marriage in 1857 to Sarah Gregory, the daughter of Bishop Gregory.

William S. Clark wrote later in his memoirs that he regarded the brothers’ withdrawals as ‘altogether excessive’ and said:

it would take long to trace out the causes of the losses … much was due to inefficient management, leading to heavy accumulation of unsaleable stock. The reduction of capital through the withdrawals … led to constant difficulties in meeting the liabilities of the firm.

The firm’s accountant, James Holmes, did not help matters. He managed to ‘lose’ the stock accounts at the end of 1859, and when the books were retrieved a year later it was discovered there had been a net loss over two years of £2,679. 17s. 10d. Holmes would become a divisive figure over the next couple of years. Cyrus thought him indispensable; James regarded him as a liability.

Under the terms of the brothers’ partnership, any withdrawals from capital were allowed only if both men agreed to them. As it turned out, every single withdrawal from 1849 – except for one – was made without joint agreement. Furthermore, taking a lead perhaps from his superiors, Holmes, who had negotiated a 5 per cent share in profits in addition to his salary, set about making withdrawals for himself in anticipation of any future profits. Closer to home, Alfred, Cyrus’s son, was also receiving 5 per cent of expected profits after he joined the company as a travelling salesman.

It was becoming hard to see where growth could be forthcoming.

![]()

Trade to Australia and other colonial countries had dipped – but the partners persisted with their battle to win over Australia. In the early 1850s, the Clarks had sent footwear to Sydney, Adelaide, Melbourne and Brisbane, with positive results, especially in children’s ankle-strap shoes and women’s slippers. But by 1857, shipments had ceased completely and would not pick up again until 1859. Samples were sent to New Zealand in the hope that this would become a new frontier, particularly in Canterbury, where wealthy colonists were arriving ‘cabin-class’ rather than ‘steerage’ as had been normal for other immigrants. But results here were also disappointing. Consignments were dispatched to South Africa in 1861, but were not repeated and trade with America and Canada was proving difficult because of the restrictive tariffs. A goloshed boot with fur on the inside was made especially for Canada in 1859, but its rubber component was subject to 25 per cent import duty, making the price unattractive to Canadian consumers.

Financial imperatives at home meant that Clarks refused to offer extra credit to its customers in Australia, who in turn cancelled their orders. Australia had always been an outlet for surplus stock and Cyrus and James were keen to keep this market going for as long as they could. ‘We do not quite like giving up altogether – it is buying experience,’ said James, while admitting that trade with Australia was ‘disastrous in the extreme’.

It was not promising in the UK either. In 1858, output was cut dramatically following overproduction during the two previous years. Staff were laid off and it would prove tough to replace them once business finally began to improve in 1864. Wages were rising, partly because other shoe companies were offering inducements to Street workers if they moved to a different part of the country. In a letter to a fellow shoemaker in 1860, James observed: ‘We do not find our workpeople as tractable as they were 10 years ago, especially with any new work’.

On another occasion, company documents concluded that:

… since the introduction of sewing machines and riveting there has been such an increase in competition that the shoe trade has not been in a very satisfactory state.

But Cyrus and James remained steadfast in their commitment never to compromise on standards, striving, as James put it, to ‘keep up the quality of our goods to make such as a bespoke shoe need not be ashamed of’. Producing ready-made shoes that had the look and feel of made-to-measure footwear was a fundamental plank of their strategy.

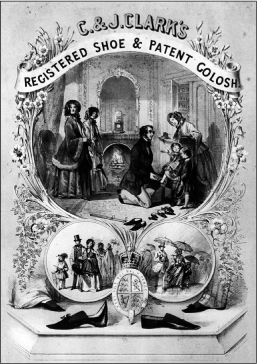

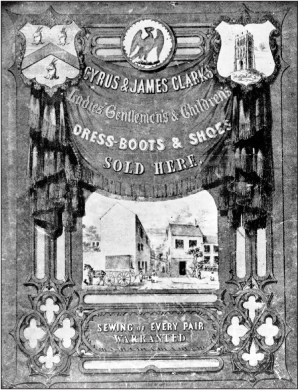

Consequently, Clarks showcards emphasised craftsmanship and tradition. One of the earliest, designed by Cyrus’s eldest son, John Aubrey Clark, in around 1849, shows the factory as a theatre stage, framed by elaborate curtains and stone masonry taken from a parish church. ‘Sewing of Every Pair WARRANTED’ is the strap-line, with ‘warranted’ in bold and in capitals. Another, two years later, features a prosperous middle-class drawing room, complete with roaring fire and grand over-mantel mirror. Well-dressed ladies watch intently as a young boy has his feet measured, a second child waiting his turn. Their mother holds a shoe in her hand as if admiring a precious piece of jewellery. The showcard names all the provincial towns where the Clarks’ shoes are sold by ‘respectable dealers’ – 77 of them in total. In London alone, there were 32 shops selling the Clarks’ footwear.

Price lists and showcards were the ways by which Clarks kept in touch with customers. Showcards were designed to be on display in shops, advertising certain lines and alerting customers to what was new in the forthcoming season. The partners were clear about how they wanted to present their wares. While other Quaker firms – such as Cadburys and Frys – advertised in newspapers, C. & J. Clark never did. The partners thought newspapers represented the mass market and they did not wish to be spoken of in the same breath as chocolate or soap. The Clarks’ strategy was to appeal directly to consumers without appearing to do so. According to The Shocking History of Advertising by E. S. Turner:

A showcard designed by John Aubrey Clark, Cyrus’s eldest son, in around 1849.

They [companies such as C. & J. Clark] were quite certain that [advertising in newspapers] was ungentlemanly … the ideal, the traditional way to do business was to surround oneself with a circle of customers and to cultivate personal relations with them; excellence of goods and word of mouth recommendation would do the rest … the last thing to do was to chalk the firm’s name on the sides of quarries or to inset furtive little paragraphs in the newspapers, in the contaminating company of truss-mongers, snuff-sellers, pox-doctors, body snatching undertakers and cut-price abortionists.

Good relations with those who sold Clarks footwear were given high priority, but at the same time the partners refused to budge on price, recognising the downward spiralling that comes when drawn into a price war. James made his position clear to shops in Scotland, when he wrote:

We may lose by refusing to take off the 2.5 per cent they now want, but this course will soon make it a worthless trade and we think it would be wiser to come to an understanding if possible.

There were also occasions when the partners were prepared to forgo a sale if they thought it would compromise their Quaker views. A business in Shepton Mallet received the following letter in October 1853:

We are duly in receipt of yours … But we feel that we can not, with a clear conscience have anything to do with an article which we believe to be destructive to the morals and best interests of the people. You will therefore excuse our declining to execute any order for mops for your brewery.

Guaranteeing the quality of shoes but offering them at much lower prices in comparison with bespoke footwear remained central to the partners’ plans. But there was still the issue of comfort. Bespoke, by definition, is custom-made. The shoe fits the foot because it is built around a unique, personalised last. The Clarks understood this and responded by offering a range of three fittings and half-sizes from one to seven. By 1855, all ladies’ boots came in this range of sizes and fittings.

Style was important, too, with Clarks quick to pick up on what was proving fashionable and popular in Paris. The brothers were anxious to register specific designs with the Board of Trade and although other companies were allowed to copy them, they had to display the name C. & J. Clark prominently somewhere on the shoe. On a number of occasions, the full weight of the law would come down on companies failing to credit C. & J. Clark. In 1854, six Dublin firms were visited by solicitors on the suspicion of pirating C. & J. Clark’s registered designs.

William S. Clark was consistent in his approval of his father’s and uncle’s stance on maintaining high standards, even in trying circumstances. As he wrote:

The greatest care was taken that threads should be properly waxed, that there should always be four to five stitches to the inch and the wear of every shoe sent out was guaranteed. In any case, a shoe that did not give fair wear was replaced by a new pair if sent back … The shoemaker’s number stamped in the waist was always a clue to the careless maker. It was this combination of solidarity and style that built up the reputation of the firm.

![]()

There were serious and continual mismatches between output and sales. In 1855, for example, sales had been more than £2,000 greater than in the previous year, but output could not cope with demand. A year later, there was a further rise in sales but this time output had outstripped demand. The same thing happened in 1857, resulting in a surplus of stock worth £12,000. George Barry Sutton, in his book C. & J. Clark, 1833–1903: A History of Shoemaking, wrote: ‘The indications are that in producing large quantities of goods in anticipation of future orders Cyrus and James had not bargained for the recession in demand which hit them and the rest of the country in late 1857.’

The yo-yo continued in 1858 when production fell by 23.5 per cent but sales did not dip by anything like as much. Consequently, opportunities were missed. And then in 1860, demand fell while production rose by 15 per cent. Evidently, the partners were finding it hard to judge the market. The start of 1860 had seen orders increase and it is likely that Cyrus and James developed an overly ambitious sense of where the trade was going. Suffice it to say that by the end of the year stocks were still rising. One explanation was that the partners wanted the factory to be working at full pace to avoid losing staff, who would be hard to replace. Another was that Cyrus and James were ‘unable or unwilling to exercise anything but a very loose degree of control over output levels’, as Sutton put it.

This showcard with its calm air of urbane sophistication gives no hint of the financial turmoil that Clarks was going through in the 1860s.

Other areas of the business were hardly thriving. The brothers’ farms, which had officially merged with C. & J. Clark, had been losing money consistently and chamois sales were too small to make a significant impact on the overall financial position. In fact, William S. Clark discovered that in 1862 only the sales of angoras, gloves and leggings (a new line) were showing a net profit. It was also onerous how the price of leather and other materials was rising year on year – and certainly faster than any increases in the price of the company’s shoes. James Clark wrote:

We had great business troubles from the bad state of trade and shortness of capital. We passed through a time of great trial and were compelled to seek the help of our friends, who most kindly came forward to aid us in our difficulties.

That was an understatement. The years 1860–63 brought C. & J. Clark to the brink of bankruptcy. There had been a profit of £3,034 in 1861, but that was not enough to offset a combined loss of £2,680 for 1859 and 1860 and a further loss of £656 in 1862. Bank loans had reached nearly £11,000 and Thomas Clark, the cousin who had become a sleeping partner between 1849 and 1854, once more lent a total of £5,500 from 1858 to 1862. By June 1863, Cyrus and James would have no capital in the business at all.

Stuckey’s Banking Company had begun to take a firmer line in May 1860, when the bank’s secretary, Walter Bagehot – who went on to become the editor of The Economist and who wrote a celebrated book on the British constitution – received yet another request to increase the overdraft. His response was polite but clear:

We can readily imagine that your trade has suffered from the circumstances you mention, and that your stock of manufactured goods is larger than usual at this season in consequence. This however is a contingency to which all business is liable and shows the necessity of a reserve of capital to meet it, as I have frequently taken the liberty of pointing out to you when we have been discussing freely the position of your concern.

The partners did not appear to take much notice, prompting Bagehot to write again a few months later, pointing out that the company was continuing to disregard its maximum overdraft limit of £2,800. Such letters became more frequent. In March 1861, Stuckey’s Banking Company said it would lend the Clarks no more money unless current advances were addressed, although Bagehot went out of his way to be encouraging:

In reply to your observations respecting the securities we hold, and the confidence we have hitherto placed in you we can only assure you that there is no change in our sentiments regarding you in any respect. We have quite the same confidence in you and the same disposition towards you as we have had hitherto but as we told you when you were here, the past course of your account for many years has determined us to definite restrictions regarding it in future.

Today, it is common for firms to hire management consultants in moments of crisis. In 1863, Thomas Simpson, a cousin by marriage to Cyrus and James and a great friend of the family, was asked to carry out an independent investigation and compile a financial report on C. & J. Clark. Simpson had run a successful cotton-spinning business in Preston, Lancashire, and had moved back to Street on his retirement to live with his mother-in-law, Martha Gillett. He was to become an important business confidant to William – as he had been to Cyrus and James. Indeed, it was Simpson who urged the partners in 1850 to implement a new system of accounts, writing to James saying it was ‘the greatest want in your business’.

Simpson liaised with Thomas Clark in his investigation, first soliciting a promise from the partners that they would ‘lay the full facts of their position before him’. It was to be an exacting and, at times, harrowing task. William wrote later how Simpson had intimated that had he known at the outset the full extent of the financial chaos he would have advised that the business be closed:

While he looked on the case as almost hopeless he thought with the introduction of further capital and a complete change of management there was a possibility that the business might be saved … it was never suggested that there was any wilful concealment from him but it took time to get to the real meaning and value of many items in the balance sheet, and affairs were in so critical a position that a decision had to be come to at once whether to go on or to stop and call creditors together.

Simpson’s findings showed that over a fourteen-year period, Cyrus had withdrawn £17,890. 18s. 5d. and James £10,358. 3s. 2d. In James’s case, it meant that already by 1860 his capital in the business had shrunk to a mere £1,157, while Cyrus was in debt to the tune of just over £10,000, a figure that Simpson increased to nearly £12,000 once he had factored in a bank loan Cyrus had secured on the deeds of his house, Elmhurst.

It was during this inquiry that Thomas Clark, who in 1863 was 69, was told that the firm was in no position to pay him the agreed 7.5 per cent on his loan. It would be reduced to 5 per cent with immediate effect. Thomas accepted the new rate and, with the encouragement of Simpson, supported the idea of persuading outsiders to loan capital to C. & J. Clark on a short-term basis. But there would be one clear proviso: Cyrus, James, and Cyrus’s son, Alfred, must relinquish all responsibility for the day-to-day running of the business. Furthermore, the brothers would only be allowed to withdraw a combined total of £500 from the business in any one year. It was decreed that Cyrus’s limit would be £200 a year and James’s would be £300.

These strictures were long overdue. From 1849 to 1862, Cyrus, the worse culprit, withdrew on average £1,278 a year from the business when his average annual share of profits had been only £824. Such reckless behaviour meant it was harder for the partners to take a stronger line when the likes of James Holmes, the accountant, and Alfred, also sought to take money out of the business. As Sutton described it in C. & J. Clark, 1833–1903: A History of Shoemaking:

In their financial affairs, the partners had displayed none of the qualities of determination and foresight which had characterised their achievements in the fields of production and marketing. Whilst devoting a great deal of time and energy to securing outside monetary help, they had exhibited no competence in, and little interest for, the day to day administration of finance.

Simpson knew that only a complete change of management would throw C. & J. Clark a lifeline, and he knew that only the promise of new management would encourage friends and cousins to provide what is known today as a ‘bail out.’ And so, in addition to Thomas Clark, whose investment now stood at £13,000, seven other investors came forward, several of whom had helped rescue the company two decades earlier. George Thomas, a Quaker friend from Bristol, loaned £2,500 and Francis J. Thompson, who had helped Simpson in his financial review, offered £1,300. Thompson, an ironmonger from Bridgwater, was a first cousin of Cyrus and James. His brother, Alexander, agreed to invest £500. Further help came from Charles and Thomas Sturge, who both gave £500, as did George Palmer and his younger brother, William I. Palmer, who were first cousins once-removed of James and Cyrus.

The Palmers, who came originally from Long Sutton, Somerset, were in the biscuit industry after joining forces with Thomas Huntley, their cousin by marriage. Huntley was born in 1803 in Swalcliffe, near Banbury in Oxfordshire. His father, Joseph Huntley, was a baker who moved to Reading in 1811 and established a bakery in 1822. George Palmer had, like James Clark, been to Sidcot School, leaving at the age of fourteen to be apprenticed to an uncle as a miller and confectioner.

Thomas Huntley and George Palmer became business partners in 1841, operating out of a small shop in Reading’s London Road, directly opposite a posting inn where travellers waited to board their coaches or change horses. Huntley took care of the baking, while Palmer worked on developing the first continuously running machine for biscuit manufacturing. By the time the Clarks asked for financial assistance in 1863, Huntley & Palmer was producing 100 different varieties and the plant in Reading was the largest biscuit factory in the world.

With just short of £20,000 worth of loans in the bank, Thomas Sturge insisted that a trust deed be drawn up, signed by all investors, confirming that Thomas Simpson and Francis J. Thompson be appointed inspectors of the business and given executive powers to safeguard the future.

In a letter to a friend dated 30 April 1863, James admitted the situation was far worse than he had realised: ‘I seem now clearly to see that we were only rescued when just on the brink of a precipice from which we could not have rescued ourselves’.

William S. Clark was only too aware of what was required. The promise of change had to be delivered.

The financial question being thus put on a more solid basis the inspectors [Simpson and Thompson] had to consider in whose hands the future management of the business should be placed … They made very careful inquiries of those in responsible positions in the factory and searching examinations of the partners and their sons as to the part they had taken and their views as to the conduct of the business; a good deal of this naturally transpired in T. Simpson’s full investigation of the state of affairs before he undertook to try to put things straight.

Modesty may have prevented him from adding that the ‘careful inquiries’ and ‘searching examinations’ led to only one overwhelming conclusion. William S. Clark, aged only 24, was to be handed full responsibility for C. & J. Clark on 31 May 1863, a position he would hold with unrivalled success for the next 40 years.