CHANGE CAME FAST. In fact, the turnaround was of such magnitude that even William S. Clark may have been surprised by the outcome. When he wrote about it many years later, he attributed much of the transformation of C. & J. Clark to his benefiting from seeing first-hand the inefficiencies of the previous era while working with his father and uncle. And now that James and, in particular, Cyrus (who was 62 in 1863 and in poor health) were no longer in charge of day-to-day affairs, William could set about making the necessary improvements unimpeded by intervention from the founders. Referring to himself in the third person, William wrote:

Everything in the business had to be conducted with the most rigid economy … W. S. Clark, having known only too well where some of the worst leaks had been under former conditions, though vainly striving to get them stopped, was very soon able to alter much that had gone.

The accounts told their own story. During the four and a half years from 31 December 1858 to the day William took control at the end of May 1863, there had been a net loss, whereas in the four and a half years starting 31 May 1863 and ending 31 December 1867, the business made a profit of £14,400. William, given to understatement, said these figures ‘put a very different aspect on the state of affairs’.

Thomas Simpson continued in his role as an adviser, something William described as:

… invaluable, though occasionally his lack of acquaintance with the technical difficulties of the very complicated shoe business, so totally different to the comparatively simple process of cotton spinning [Simpson’s business before his retirement], made it difficult for W.S.C. to carry out his [Simpson’s] wishes.

High on both William’s and Simpson’s list of priorities was the repayment of the loans awarded to the company through a specially drafted Deed of Covenant. At the same time, it was evident that additional money had to be found in the latter part of 1863 and 1864 and yet again it was Thomas Clark – always known to the family as ‘Cousin Thomas’ – who stepped into the financial breach once more, sending William £2,300 to meet ongoing expenses. In addition, Stuckey’s Banking Company, encouraged by the new management set-up, advanced £1,000 on the condition that the company’s overdraft be reduced to £2,500 over the next two years.

In 1863, the total debt owed to fellow Friends amounted to £19,050. By 1868, it had come down slightly to around £18,000, but the subsequent four years saw it diminish considerably. Accounts in 1872 showed Friends’ loans had been reduced to just under £3,750, while bank loans were £5,064 and the overdraft stood at a comparatively respectable £1,783.

That William threw himself into his new responsibilities with boundless energy and enthusiasm there can be no doubt. Factory hours in 1863 were 6 am to 6 pm, but the new chairman was putting in eighteen-hour days himself and took a mere fortnight’s holiday in the first two years of his chairmanship. He recorded later that he had only two full-time foremen to help him in the factory – ‘but poor ones at that’ – during a period when he sought to end the practice of out-working and to stop the ‘horror of the treatment of small boys in the home workshops’.

His weapon to achieve this was new machinery and his main lieutenant in this endeavour was John Keats. One particular process that exercised William and Keats was finding a means of closing the uppers with waxed thread. No machine was capable of this because the wax in the thread habitually clogged the eye of the needle. Keats – whom William described as a ‘very erratic genius in the machine room’ – came up with the idea of using a hook in place of a needle. And it worked. This was especially crucial for the sales of heavy waterproof boots.

‘Made strong and stout in the soles and uppers to keep the feet dry and warm, in spite of dews and wet grass’ boasted an 1864 Clarks showcard. A patent for this invention – known as the Crispin machine, in honour of St Crispin, the patron saint of shoemaking – was taken out in 1864 in the joint names of William S. Clark and John Keats, and Greenwood & Batley, a company in Leeds, was commissioned to make and sell them under licence.

Adapting these machines to sew on the soles of boots was the next challenge. It was hoped that a variation of an invention by Lyman Blake would do the job. Blake, who was from Massachusetts in the USA, worked in the shoemaking business all his life, at one point joining Isaac Singer’s company, Singer Corporation. By 1856, at the age of 22, he had become a partner in a shoemaking firm and two years later received a patent from the United States government for inventing a means of attaching the soles of shoes to their uppers. William and Keats had in fact seen the machine in action at the London Exhibition of 1862 – but had not been overly impressed.

William decided against its use – a decision he explained in his memoirs as being:

… partly [because of a] strong objection to a chain stitch and partly because anyway the work was not satisfactory. The reason for this was at that time the horn was stationary and it was only by the introduction of the rotating horn not long after that that the machine became a success.

But the Blake Sole Sewer, as it was called, had proved hugely effective during the American Civil War and at the very least had convinced William that if:

… C. & J. Clark was to hold its own in face of constantly increasing competition it could only be by the adoption of these new American methods … [and] as the Trade Union then had no foothold in Street they hoped the change might be made here without undue friction.

He was proved right – and wrong. Improvements to Blake’s machine gathered pace, principally due to modifying its stitching unit. This involved the addition of a ‘whirl’ device which fed a loop of thread into the hook, copied from the original Crispin machine, but in a rare oversight, the ‘whirl’ had been omitted from that invention’s patent. Blake’s machine was too big to operate in the home of an outworker and required an overhead power source to operate the belt. This was fortunate from William’s point of view because it quickened the process of gathering workers up into the factory.

William and Keats pushed on with their plans. They had success with a machine that burnished the edges of soles, a significant follow-up to James Miles’s mechanised sole-cutter that trimmed soles exactly to size. They also invented a press for the building and attaching of heels, the first such machine to be used in Britain. On this occasion, rather than taking out a patent they simply operated it in secret without any fanfare – after reminding themselves that they were after all in the business of making shoes, not selling shoemaking equipment.

William nearly committed the company to screwing on soles as an alternative to both riveting and sewing after being introduced to an inventor who claimed to have developed a machine capable of fastening soles in that way. A special room in the factory was set aside for this innovative piece of equipment, but the delivery date came and went and when, a year later, the inventor – who was from Stalybridge in the foothills of the Pennines – said that he was ready to make the delivery, William wrote a thank-you-but-no-thank-you letter.

We fully indorse [sic] your opinion that boots and shoes must all be made by machinery before long but are not so sure that the public will not prefer having them sewed to screwed.

There were other frustrations in those early years of William’s leadership. For all his long-term commitment to machine-made shoes, there was the short-term, uncomfortable truth that labour costs on boots made by machine were often one-third per pair more than had been predicted. In 1866, William wrote to Greenwood & Batley complaining of:

… a constant drain of expense upon us from which we have as yet reaped no advantage of any kind whatsoever, and none of the goods made hitherto have realised what they have cost us in wages and materials.

A few months later, he was more optimistic: ‘We hope in time to make a paying affair of it, as we are still convinced there is something valuable at the root of the system’. By 1872, the ‘something valuable’ element became clearer with the adoption of a bent needle that allowed soles to be sewn while still on the last. This prompted William to declare:

We are perfectly satisfied with the work … we believe most of our customers sell it as hand work … in fact, to give you our honest opinion, we are satisfied that no system at present before the public can in the long-run compete with it, and we are indifferent as to anyone else taking it up.

![]()

Cyrus Clark died on 14 December 1866 at the age of 65, only a few weeks after the death of his wife. There were no obituaries, but in Clarks of Street, 1825–1950, Cyrus is spoken of as ‘warm-hearted’ with an ‘indomitable perseverance in carrying out any object on which he had set his mind … no obstacle, or, as he would say, no “lion in the path” was allowed to stand in the way’.

His death led to an unseemly and unfortunate three years of wrangling between his brother, James, and Cyrus’s surviving family, particularly his youngest son, T. Beaven Clark. James described it as ‘passing through some of the deepest trials’ of his life, which he only managed to negotiate with the ‘loving support and sympathy of my precious wife’.

Two years before Cyrus died, he and James had renewed their partnership agreement whereby they or their heirs had equal shares in the profits of the company for seven years. Therefore, upon his death, half the profits of the business continued to be paid into Cyrus’s estate and it was left to the two executors of his will to see that this happened. The executors were Jacob H. Cotterell and William I. Palmer, the Quaker cousin who worked in his family’s biscuit business in Reading.

Some months after Cyrus’s death, Cotterell also died, leaving Palmer as sole executor. Palmer was, according to William:

… anxious to wind up the trust affairs as far as possible and suggested that an agreed sum should be paid into the estate to cover the share of profits for the remaining years of the partnership and all claims there might be on the business for goodwill etc

It was agreed that negotiations should begin, with Palmer representing Cyrus’s family and Thomas Simpson negotiating on behalf of James.

An agreement was reached for a payment by James of £1,500 as a goodwill gesture. In his account of this episode, William quoted Palmer as saying:

If James Clark agreed to the terms he [Palmer] proposed as his brother’s executor it would place him [James] in a position in which no one could find fault with him.

James signed his name to the settlement, but Palmer then informed him of Cyrus’s wishes that accompanied his will, making it clear that he wanted his son, Beaven, to succeed to his share in the business. As William recorded:

For reasons that seemed to him conclusive James Clark replied that after long and careful thought he had come to the conclusion that this was quite out of the question and there the matter rested.

But it did not rest there. Beaven, who was employed in the business as a book-keeper, insisted that his family had ‘an absolute right to a half share partnership in the profits of the business in perpetuity’ and not just for the remaining five years of the partnership. James disagreed. He said that when the last deed of partnership was drawn up between the brothers in 1864, Cyrus had tried to insert a clause ‘securing his family this half share, not in goodwill but in any further partnership’ but had eventually backed down on the proviso that a line be included simply expressing his hopes that one of his sons would come in as a partner.

James, distressed and frustrated, was prepared to be generous to his late brother’s family but would not give way on the matter of the future partnership. And William took exception to his father being accused of ‘not doing his duty by his nephews’. The situation was weighing so heavily on William’s mind that at one point he contemplated walking away from the business altogether. Certainly, that was the inference from a letter he received from Simpson, stressing that:

… you owe a great deal to your father … and it will hardly look well that you should fly from the post of duty when trials and annoyances have to be met and overcome.

Arbitration ensued. Cyrus’s family asked for a fellow Friend, Richard Fry, from Bristol, to act on its behalf; James sought the services of Lewis Fry (no relation to Richard), an eminent Quaker also from Bristol, who later went into politics. George Stacey Gibson, from Saffron Walden, a leading member of the Society of Friends on a national level, was asked to be an independent voice of reason.

Delicate deliberations took place at the home of Cyrus’s and James’s older brother, Joseph, and lasted a full day. T. Beaven Clark and his brother, Alfred, read out their statements, as did James and William. Alfred was speaking more on behalf of his brother than himself because he had been well looked after financially through his role in charge of the firm’s London office in Sambrook Court, Basinghall Street, which was set up as an independent venture in 1863. Cyrus’s eldest son, John Aubrey Clark, a qualified land surveyor who had played little part in the firm, remained silent.

Following that meeting, Simpson wrote to James on 10 June 1869 with encouraging news:

I duly reached home last night after a very satisfactory interview with cousin W. Palmer who said, ‘if they [Cyrus’s family] do not accept it now, I will have nothing more to do with it.’

And he sought to assure James that he was right to make a stand:

I have carefully read over the memorandums left by your brother [Cyrus] and although they deeply excited my sympathy and sorrow on his behalf, the perusal has only the more strongly confirmed my previous opinion on the whole question. Everything is stated in such a way as to give an incorrect estimate of the facts of the case and for the express purpose of exciting sympathy, but the false gloss cannot of course deceive me, as I know the facts too well … if the proposition is now declined it would be wrong to take it up again.

But it was taken up again. In fact, it was a further five months before matters were brought to a close, during which time tensions between James’s and Cyrus’s respective sides of the family worsened. Simpson wrote to James on 22 June 1869 recommending it would be wise to ‘have no further conversation with either Beaven [T. Beaven Clark] or Alfred or anyone else on their behalf on any subject at all connected with the negotiations’. He added:

Keep up your spirits for all may yet turn out better than you now expect. You have right on your side … you have a wife and children who are your first duty, and their interests have for years been sacrificed to the interests of your brother and his family.

On 11 November 1869, James issued a signed statement that he hoped would assuage the growing resentment towards him from Cyrus’s family:

The Arbitrators having expressed their opinion that the observations made by James Clark upon his late brother’s conduct were of a more severe character than the circumstances warranted, and that some of such observations might be understood as reflecting upon Cyrus Clark’s character, James Clark stated that he had never intended to make any reflections upon his brother’s straight-forwardness and integrity and that he entirely withdrew any observations which might bear that interpretation.

Five days later, the arbitrators ‘unanimously’ decided that ‘either some representative of the family of the late Cyrus Clark be admitted to a share in the said business or that a compensation for goodwill be paid to the estate of Cyrus Clark.’ The amount was set at £2,250 – rather more than the originally agreed sum of £1,500.

William I. Palmer immediately wrote to James and pleaded with him not to make a hasty decision. James wrote back on 18 November 1869 saying that although the award was higher than he had anticipated he felt ‘well satisfied’ and was pleased to bring matters to a conclusion. He would opt to make the payment:

It has been a great relief to me to be so entirely liberated, as only such an award could have liberated me, from a Partnership that has for many years been such a burden that I could not feel at all justified in leaving it on my children’s shoulders.

Lewis Fry, the Friend who had supported James, told him:

We were all very strongly impressed with thy candid and very honourable conduct in at once surrendering the agreement which had been signed. Hadst thou insisted upon it, as many persons would have done, I believe we should have felt that it would have precluded our making any award.

And Richard Fry, representing Cyrus’s family, was similarly impressed, telling William: ‘When thy father has carried out these terms no one can say but that he had done everything for his nephews that he could be expected to do’.

The immediate response of the nephews is not documented, but Beaven gave short shrift to James’s subsequent offer that he might become a partner in the rug-making side of the business. William never expanded publicly on this for fear of ‘the risk of injustice to James Clark’s memory’, adding how:

… time gradually restored friendly feelings with his brother’s family. He always had cordial feelings towards them and deep regard and affection for the memory of his brother from whom he had received such unfailing kindness in his early days.

Palmer, who, although acting on behalf of Cyrus’s descendants, had been thrown into the role of peacemaker, told James he hoped never again ‘to have the misfortune’ to be a sole executor ‘in a business under similar difficulties’. Simpson, who had been bullish in representing James, was less magnanimous. He wrote to his client applauding his decision to make the goodwill payment rather than allow Beaven to be a partner in the business, adding:

You have been sponged nearly dry by one thing or another on account of the family but I believe God will return it to you again in added prosperity, and your conduct throughout I consider to have been a very great honour to you whatever others may say … I consider it [the award] to be an unjust one but it has to be abided by.

Despite the award, discordant rumblings continued. Bessie Clark, Cyrus’s daughter, was under the impression that James never actually got round to signing his statement about not wishing to cast aspersions on Cyrus’s character. James patiently wrote to her on 21 March 1870, stressing how his only desire had been to ‘clear myself from the charge of having ever intended to cast any imputation on my brother’s perfect honesty and integrity’. But Bessie was still not convinced. She thought James had not addressed directly the question of signing or not signing the document. James wrote to her again, spelling out his position even more clearly:

I quite intended my letter of the 21st to confirm the paper I signed at the time of the Arbitration and I had no idea that it could be understood in any other sense.

Over the next few months, James wrote twice to his nephew and eventually, almost a year after the announcement of the settlement, Beaven responded in a conciliatory tone:

Dear Uncle, I am extremely glad to receive the two letters thou has addressed to me and gladly accept them in the full sense in which I trust they are written. I most sincerely thank thee for the expressions of regret they contain and for the frank acknowledgement of thy feelings with regard to my dear father …

Beaven also conceded that he had been hasty in rejecting James’s offer to get involved in the rug business:

I consider myself to blame for not speaking to thyself when I first heard of the state complained of as mutual explanations might probably have prevented the unpleasant misunderstanding which has occurred.

As it turned out, James and William decided later that same year in 1870 that the rug business would be separated from the shoe company. It was to be called Clark, Son & Morland, with James, William and John Morland, James’s son-in-law, as partners. James and William had a quarter share each and John a half share. The headquarters was at Bowlingreen Mill, a tanning factory owned by James, which he had inherited from his father, though it was not long before the business moved to Northover, a nearby tanning yard bought especially for the purpose. Following the new status of the rug company, James wrote:

By the kindness of my friends, and the skilful and diligent management of my son, William, I was released from the great harassment I had endured for many years, working with insufficient capital entailing some years heavy losses instead of profit.

Cyrus’s death and the subsequent fall-out came shortly after William’s marriage at the age of 27. His wife, Helen Priestman Bright, was a year younger than him and they were to have six children, two sons and four daughters. Helen was the only child of John Bright by his first wife, Elizabeth Priestman. Bright – or to give him his full title, The Rt Hon. John Bright MP – was the much admired and hugely influential Liberal politician who, along with Richard Cobden, formed the Anti-Corn Law League.

An MP for 46 years, Bright was regarded as one of the greatest orators of his generation. His father, Jacob, was a Quaker who ran a cotton mill business in Rochdale and John remained proud of his radical religious roots. His first public speech was at a Friends’ temperance meeting when he got his notes hopelessly muddled and began to break down in tears. The chairman told him to abandon his text altogether and just speak his mind. Which he did, gaining a rousing reception. His talent for off-the-cuff oratory never faltered from that moment on.

Greenbank, where William S. Clark and Helen Priestman Bright lived after marrying in 1866.

Bright was a strong supporter of the 1867 Reform Bill and is credited with inventing the expression ‘flog a dead horse’ which he used in the House of Commons, telling MPs that trying to rouse Parliament from its apathy on the issue of electoral reform would be like ‘trying to flog a dead horse to make it pull a load’. He also coined the phrase ‘England is the mother of all parliaments’ while rallying support for a wider electoral franchise.

William and Helen began married life in Greenbank, so-named after the Rochdale home of John Bright. It was an old farmhouse on to which William had built two Victorian wings. The bay window was re-assembled from the Clarks showcase stand at the Great Exhibition of 1851. The family remained there until 1889, when William commissioned his favourite architect, George Skipper, whose main bulk of work was in Norfolk, to build a new house further away from the factory. This was called Millfield and is now part of the 1,200-pupil co-educational independent school of that name, which was founded in 1935. William and Helen were already familiar with the area around Millfield because in 1880 their youngest child, Alice, contracted tuberculosis aged six, and rather than send her abroad for the mountain air as so many tuberculosis victims were, they built a Swiss-style house called The Chalet, where Alice sat during the day and often slept at night. She survived.

The Chalet is now used as a chapel for Millfield School and is the oldest building on campus. Millfield House remained in the Clark family until the 1950s, with the school paying rent for its use. At first, it was where Millfield’s founder, Jack Meyer, lived, before it became a boarding house for boys.

![]()

James and William formed a new partnership in 1873 and it was another seventeen years before James finally retired aged 79. Part of the agreement between father and son amounted to a job description of which most people can only dream: ‘James Clark is not required to give more time to the business than is convenient or agreeable to himself’.

The capital within the company at the start of this new partnership was £9,505. 4s. 2d., of which James’s share was £7,203. 3s. 9d. and William’s £2,304. 0s. 5d. Profits were to be divided equally.

Crucially – and contrary to what had seemed possible only a few years earlier – by 1871 most of those who had loaned the company money in 1863 had been repaid in full. In triumphant mood, Thomas Simpson sent the deed governing the agreement between Clarks and its creditors to William, with a note saying: ‘I should consign [the Deed] to the flames which has been the fate of all the other promissory notes’.

William no doubt felt greatly relieved. Honour had been upheld and the Quaker edict about living free from debt had been restored. William resolved never again to allow the company to operate without adequate reserves. He was also resolute in his commitment to reinvest profits whenever it was expedient to do so – and not take money out to build new homes or prop up struggling associated enterprises.

Millfield House, designed in 1889 by the architect George Skipper as a family home for William S. Clark. It is now a boarding house for Millfield, a leading public school.

There were good years and there were less good years between 1863 and 1879, during the height of what is known as the second industrial revolution or the technological revolution. The development of the railway system allowed goods to be transported at an accelerated rate, but this had the effect in some parts of the country of saturating the market with products that could not be sold. This surplus in turn forced prices to drop as businesses tried to secure capital returns by making quick sales of their assets.

Clarks output remained strong. The company produced 78 per cent more pairs of shoes during the sixteen years from 1863 to 1879 than in the sixteen previous years, and in some years output actually doubled. In terms of numbers, Clarks produced 180,000 pairs of shoes in 1863. By 1903, that figure had risen to 870,000. And what was especially gratifying was the way the footwear industry in general, and Clarks in particular, defied the national economic mood. When the country was in the grip of recession in 1875 and 1876, Clarks increased productivity by 18 per cent.

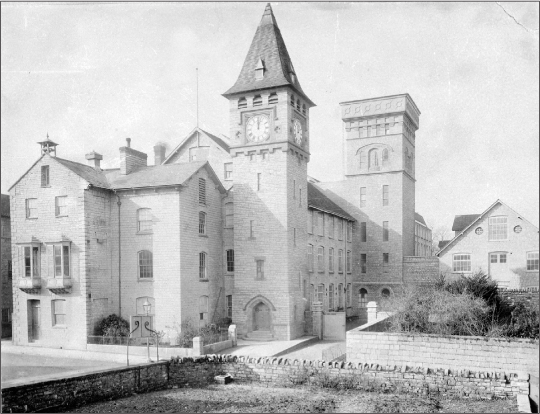

The main Clarks factory in Street in the late 1890s, seen from the High Street. This view clearly shows the clock tower built for Queen Victoria’s jubilee in 1887 and in the background the water tower (built in 1897) and the ‘Big Room’.

William had made a point of saying in 1863 that he wanted to reduce the number of lines the company produced, but by 1896 there were no fewer than 352 different models of women’s footwear alone. And whereas in 1863 Clarks produced more boots than shoes, this had evened up by the end of the century, with shoes representing some 50 per cent of total output.

Some of the more popular lines from early in William’s career included: the ‘Gentleman’s Osborne’ boot (1858); the ‘Gentleman’s Prince of Wales’ shoe (1863); the ‘Lady’s side-spring’ boot (1864); the ‘Lady’s Lorne Lace’ boot (1871); the ‘Lady’s cream brocade side-laced’ boot (made originally for the 1862 International Exhibition) and the Child’s ‘Dress Anklet’ in black enamel seal, which had been designed by William himself in 1856.

Quality was sacrosanct. In 1867, William, clearly irked by what he felt were inferior shoes coming into the market at comparable prices to Clarks, wrote to a dealer saying:

… the quality of our goods is so entirely different from those of Crick & Sons [a Northampton firm of shoemakers] that … we doubt if we could get up goods low enough in quality to sell where [theirs] have sold.

A little later, he explained to another dealer that ‘ours is mainly a better class trade’.

![]()

For all his determination to end the out-work system, William had to accept that even as late as 1898 some 4,800 pairs of shoes were hand-sewn by more than 150 men operating from home in villages such as Long Sutton, Martock and South Petherton, and small towns like Wells and Shepton Mallet. Most outworkers still had at least one apprentice, who lived in and received his keep in return for work. Many of those apprentices came from Muller’s Orphanage in Bristol.

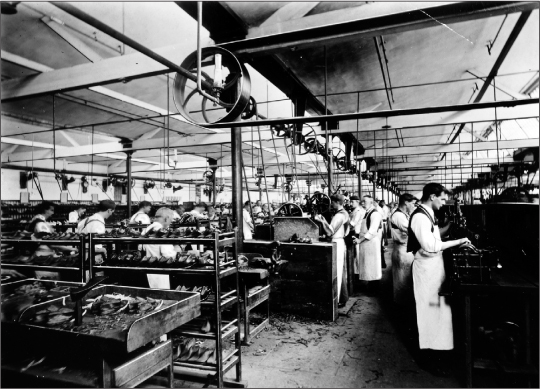

Gradually, the so-called ‘team system’ that was proving so effective in America came to the fore in Street, culminating in the establishment in 1896 of ‘the Big Room’, a building measuring 240 ft by 120 ft that was divided into a number of ‘rooms’ but with no dividing walls. These open-plan departments comprised a Pattern Room for grading and design, a Cutting Room for the preparation of uppers, a Machine Room for closing the uppers, a Making Room for lasting and sole attachment, and a Treeing and Trimming Room for finishing.

Expenditure on new equipment was as low as £69 in 1877 – less than £5,000 in today’s money – and it was only after 1878 that larger financial investments were made. Until then, William had concentrated on making sure the existing machinery was working to full capacity, but, surprisingly, in 1876, some twenty years after the first Singer sewing machine had been introduced, only 80 per cent of the footwear produced by C. & J. Clark had machine-sewn uppers.

The ‘Big Room’, seen here probably around the beginning of the 20th century. All the major shoemaking processes took place within one large open-plan workshop.

Frustrations in perfecting machine-made shoe production were compounded by Street’s insufficient labour force. It was not unusual for price lists to include an apology for production delays and promises that such hold-ups were being addressed. Furthermore, workers’ unrest was festering. In 1867, the men operating the Crispin machine in the boots department downed tools and demanded higher wages. This defiance led to further apologies for production delays, with William telling his customers that he had been persuaded to shorten the hours of the cutters and Crispin machine hands – as well as increasing their pay. A double headache.

Trade unions had been decriminalised in 1867 and the Amalgamated Cordwainers Association became in effect the first shoemakers’ union. But it made little headway and in 1874 a new union was formed: the National Union of Boot and Shoe Rivetters and Finishers, otherwise known as the Sons of St Crispin. This grouping soon established a network that helped workers throughout the country and provided such support as a funeral fund and sick pay. By 1887, it had 10,000 members. The Sons of St Crispin would change its name to the National Union of Boot and Shoe Operatives in 1898.

The union was suspicious when William brought in John Keats’s father, William Keats, to help finesse the Crispin machine, and there were soon rumours of random strikes being planned. At one point in 1877, William felt it necessary to write to Greenwood & Batley insisting:

It is a mistake to say that our factory was closed several times owing to disturbances. To the best of my knowledge this only occurred once – at the time of a strike which lasted two or three days just before W. Keats left us … although a great many other matters caused ill-feeling towards W. and J. Keats, and it was heightened by a good deal of indiscretion on their part, and as a matter of fact in the strike referred to, and which was directed solely against them, the question of the sewing machine was never alluded to by the men. I quite believe that J. Keats may be right in thinking that a feeling against the machine was really at the root of the matter. I write this fully that you may understand that, as the men never raised any direct opposition to the machine, I do not honestly see that I could put the case any stronger.

There had been a further unsettling development in 1874 when a Clarks travelling salesman, E. C. Sadler, decided to exploit the shortage of jobs for hand-sewers by setting up a rival shoe manufacturing business in Street. He made this audacious move with the support of Edwin Bostock, a shoemaker in Staffordshire, and by 1877 E. C. Sadler & Co. was employing 300 people. Sadler paid his workers better than Clarks while at the same time copying many of the Clarks’ lines, sometimes passing them off as made by C. & J. Clark. The competitive threat from Sadler’s abated in the early 1880s when, citing union interference, it moved production to Worcester and in 1897 the business was closed.

The year 1880 was a pivotal one for C. & J. Clark. For the previous 24 months, the company had been spending large sums on new technology and the ‘team system’ was being slowly implemented. To help with the latter, a man called Horatio Hodges, the son of a former Street shoemaker, was recruited to drive through the changes. Hodges had experience of working in America and was, as William put it, ‘thoroughly acquainted with the newest American machinery and systems’. But he may not have been so well acquainted with tactful man management and the need to find a common consensus. In C. & J. Clark, 1833–1903: A History of Shoemaking, George Barry Sutton wrote:

Horatio Hodges was an unfortunate choice as the ambassador of progress … He was a gifted machinery inventor and, as a local Salvation Army leader, made recruits. What he lacked, however, was the gift of understanding others of divergent views or of impressing them with his tolerance.

One of the many grievances against him was the way he tested the productivity of machines and then exaggerated their achievements. He was also unpopular for hiring boys because they were cheaper than men. The workers wanted Hodges out – and were prepared to go on strike until he was dismissed.

William flatly refused to sack Hodges and countered that only one boy had been hired in direct competition with a man. ‘Pressure was brought to bear in many ways to give [the machines] up as failure’ noted William in his private diaries.

Publicly, William made clear that if the men backed down, he would happily ensure they were secure in their jobs. But they weren’t interested. A stand-off ensued, followed by an all-out strike in May 1880 that lasted not a couple of days, like the one in 1867, but the best part of two weeks. William took a hard line during the walk-out. He said no member of a trade union would be allowed back to work and then warned that if the strike were to continue, he would be compelled to move the whole business to Bristol.

On 22 May 1880, the Western Gazette ran a story headlined ‘Strike at Messrs. Clarks Factory’:

An unfortunate dispute is now going on here. It seems from what we can gather that a foreman has introduced machinery which the men say has reduced their earnings…. The strike has since assumed a most determined character on the part of the rounders, riveters, finishers and the workpeople of both sexes in other branches of the trade …. There is now some talk of asking the firm to submit the points in dispute of arbitration and there is no doubt that great relief would be felt by all concerned on the strike if the matter could be satisfactorily adjusted.

Six days later, on 28 May 1880, the paper printed a breathless, long-winded response from C. & J. Clark:

Sir, We notice in your last week’s newspaper an account of the difficulties with our workpeople … they requested a meeting with us on Monday evening when we asked to have all their grievances submitted to us in writing that they might be fully discussed. We endeavoured to ensure that they had been mistaken in attributing their shortness of work during the past winter and other hindrances to the machinery and new system introduced in the factory and that other changes of which they complained were solely caused by a determination to improve the quality of the work turned out and that they had largely benefited from the increase in orders that had resulted from these improvements. We also pointed out that supposing all their grievances to have been well founded the straightforward course would have been to have brought them before our notice at the time they occurred and not to bottle them up and wait till the season of the year when they knew that a disturbance would cause us the greatest inconvenience and then suddenly threaten to strike unless we discharged our foreman adding that if we had been so cowardly as to yield to such a threat and thus commit an act of injustice it could not have been to increase their respect for us. The next day they decided to withdraw their demands and return quietly to work. We wish to take this opportunity to state that we think that great credit is due to them for the great order maintained during a fortnight of such excitement of feeling.

We are respectfully CJC

Once the strike had ended, William moved Hodges quietly out of Street, and he left the company altogether in 1887. This was the only all-out strike that Clarks encountered then or since. Later, William attributed the unrest to ‘certain information that came to hand’ but was sparing with the detail, saying only that ‘all the difficulty at Street was caused by agents of the Trade Union who vowed that the machinery and system should be put an end to and used their utmost efforts to stop it’.

Kenneth Hudson, in his 1968 book Towards Precision Shoemaking, said William opposed the trade unions precisely because he:

… believed passionately in the importance of good relationships’ [between employer and employee] … He saw no virtue or value in discussion between representatives of capital and representatives of labour. Such meetings, he felt, made understanding and fair treatment less likely, not more.

William was something of a renaissance man. He was a keen reader and took a great interest in architecture and engineering. Sporty as a child, he remained a strong swimmer and skater throughout most of his life. But he also managed to find time to involve himself in almost every facet of local affairs. He was an Alderman in the County of Somerset and a magistrate; he acted as treasurer of the Western Temperance League and was chairman of the Central Education Committee of the Society of Friends. For 24 years he was a member of the local authority, first known as the Local Board, later the Urban District Council.

Quakers took seriously their wider commitments. They believed in the sacredness of human life and the acceptance of all people, regardless of gender or colour. As enshrined in the words of John Bellers in 1695, recorded in William C. Braithwaite’s The Second Period of Quakerism:

It is not he that dwells nearest that is only our neighbour, but he that wants our help also claims that name and our love.

The Quaker desire to create a convivial working environment would lead other Quaker families to build whole new towns on the foundations of their high-mindedness. In 1893, after Cadbury had opened a factory in Birmingham fourteen years earlier, it established a new community for the workers and their families that it called Bournville. This occupied a fifteen-acre site, ideally placed for rail and canal links, and everything was, as the company put it, ‘arranged for well-studied convenience’. A founding principle at Bournville was that ‘no one should live where a rose can not grow’.

Not to be outdone, Rowntree, Cadbury’s big rival, acquired a twenty-acre site just outside York, and Reckitt, a Quaker company which produced household cleaning products, established its own model society near its factory in Hull. That is not to say that the entire workforce of these companies thought they were living a model existence. Generosity sometimes came with a price. The Rowntree family went as far as deploying supervisors to monitor behaviour to and from work and for a short period refused to employ single mothers.

Likewise, men who married their pregnant girlfriends were not entitled to the customary three-day, fully-paid honeymoon and those missing work through venereal disease did not qualify for sick pay.

Rules such as these were in keeping with Quaker thinking but, as James Walvin wrote in The Quakers: Money and Morals:

… what convinced Quaker magnates of their approach, was not so much the moral strength of their position but its commercial results: managing the labour force decently was good for business.

There was no question of depositing money in off-shore bank accounts or amassing excessive bonuses or taking the local community for granted. Rather, the onus was on building up the community and investing in its future. At C. & J. Clark, there may have been a brief period of tension between management and workers over the introduction of new machinery, but the firm went out of its way to build an integrated society outside the factory. It bought large swathes of land on which workers could build their own homes, helped by loans offered by the company. A terrace of cottages, for example, on Somerton Road, built in the 1830s, had been bought by Cyrus Clark, and additional houses were acquired in Leigh Road and on the High Street. Property owned by Clarks in 1882 was valued at £6,524.

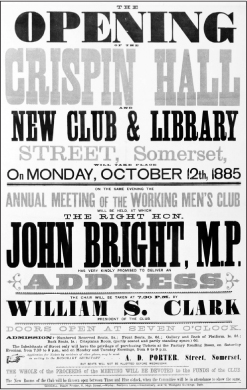

The company sponsored a Building Co-operative and land was let out cheaply for use as allotment gardens. George Barry Sutton quoted one employee as estimating that 30 per cent of Clarks’ workforce owned their homes by the turn of the twentieth century. That sense of a wider community was further advanced in 1885 when construction was completed on the Crispin Hall, a cultural and community centre commissioned by the company. Like Millfield House, it was designed by George Skipper, and was big enough to seat 800 people. In addition, there was a lecture room, library, reading room and a geological museum, with a gym and billiards room added later.

Today, Crispin Hall – listed Grade II by English Heritage – is rented to community traders and charitable organisations, and the local Women’s Institute holds its weekly market in the main hall every Thursday. The building was officially opened in 1885 by John Bright MP, William’s father-in-law, who said:

It has always been desired that the Factory and those connected with it should share the community life of Street rather than exist as a self-contained unit apart from that life.

There were annual factory outings organised by management. One, on 27 June 1885, involved a trip to Plymouth on a special train that left from Glastonbury at 5.30 am and arrived on the south coast nearly five hours later. The special fare was 4s. 3d. and was available to all those working at C. & J. Clark, Clark, Son & Morland, and the Avalon Leather Board Company, which was set up by William S. Clark as an independent company (although he was the first chairman) for the turning of scrap leather into fibre board, which was used as part of a shoe’s construction.

Poster advertising the opening of the Crispin Hall.

On this particular works’ outing, the factory band accompanied everyone to Plymouth and the return train did not pull into Glastonbury until well after midnight.

The British Trade Journal of 1887 evidently thought highly of Clarks’ general ethos, saying that it formed ‘as industrious, temperate and intelligent a community as can be met with’.

In the same year that Crispin Hall opened, Clarks acquired the Bear Coffee House, formerly Jimmy Godfrey’s Cider House – now the Bear Inn – directly opposite the factory. Once the transaction had been completed its licence to serve alcohol was immediately revoked. Then, in 1893, it was demolished and rebuilt under the supervision of the architect William Reynolds, a nephew of William S. Clark. It became known as the Bear Inn, but was granted a licence again only in the 1970s.

Crispin Hall, seen here in 1900, was provided by William S. Clark as a cultural centre for the population of Street. The hall is still in use for community and charitable events today.

Education was another priority. Cyrus’s and James’s mother, Fanny Clark, had been instrumental in founding the British School shortly after the start of the Crimean War, which then became the Board School. Later, William S. Clark built and personally financed for several years the Strode School, which was set up for boys and girls who had left full-time education at fourteen and were employed by Clarks.

Later, in the 1920s, a Day Continuation School was established for the benefit of boys and girls up to the age of sixteen working in the Clarks factory – but not exclusively so – as a means of extending their educational opportunities. Pupils would commit to one morning and one afternoon each week, their attendance being a condition of employment.

The advantages of working at Clarks were offset to some degree by lower wages compared with other shoemaking companies. Clarks was not a member of the Victorian Employers Federation, formed in 1885 to represent employers on issues of industrial and labour relations, and so it was exempted from negotiations with the unions over pay and conditions. A national strike in 1897, calling for a minimum wage, a 54-hour week, and, most notably, an end to child labour, had no impact on C. & J. Clark.

Advertisement card from 1926 for the Bear Inn (or Hotel) in Street’s High Street, opposite the Clarks factory.

Towards the end of the century, William relented over union representation, but still regarded it as a diversion. His main focus was on monitoring output and sales – something both his father and uncle demonstrably had failed to grapple with. William’s original 1863 Summary of Stock Account had analysed in detail the value of footwear output from 1851 onwards and he did everything he could to eliminate the imbalance between output and sales. As Sutton noted, somewhat complicatedly, in C. & J. Clark, 1833–1903: A History of Shoemaking:

He enumerated the wage and material costs incurred annually, making sub-divisions to show expenditure on different classes of employees and components. These costs, hereafter called direct costs, were deducted from footwear output and sales to give ‘gross profit on goods made’ and ‘gross profits on goods sold’. Other expenses incurred in the footwear trade, hereafter called indirect costs, were enumerated and deducted from each of the gross profit figures yielding ‘net profit on goods made’ and on goods sold. Finally, each item of costs, expenses and profit was expressed as a percentage of both goods made and goods sold. This dual set of figures provided a comparison of costs with expected results, expressed in the value put on goods made, and with actual achievement expressed in sales.

This policy paid off. Between 1863 and 1904, there were only ten individual years when the number of pairs produced exceeded the number ordered. And while the founders never placed a great emphasis on the accuracy of their accounting, William insisted on preparing accounts half-yearly rather than just annually.

![]()

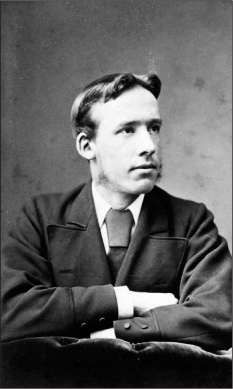

James Clark retired in 1889 and a new partnership was formed between William S. Clark and his brother, Francis Joseph Clark. Like William before him, Francis (always known as Frank) had been sent to the Quaker Bootham School in York, and had joined the firm at the age of seventeen in 1870. He was fourteen years younger than William. Within a short time, he was managing the cutting room and purchasing materials for uppers. Apart from one year studying at University College London, his whole career was spent in the family business. In July 1881, William wrote to his brother saying how he wanted him to:

… feel now more than ever … thy full share of the burden of the business and … that thy future position in the business must mainly depend on thy making thyself necessary to the business.

This partnership was to last fourteen years, concluding only when the business became a private limited company in 1903. During this period, the second-generation brothers ploughed more than four-fifths of profits back into the business, a level of reinvestment unheard of while Cyrus and James were partners.

The footwear market, meanwhile, was changing. Ready-made shoes were now the norm rather than the exception and the 1890s saw an influx of cheap shoes from America, Switzerland, France and Austria. Department stores – or, at least, buildings where a number of different shops sold their wares – were on the increase. C. & J. Clark, however, regarded its product as superior to anything found in a department store and continued to sell only to wholesalers and specialist shoe shops. Its shoes were given suitably establishment names: ‘Lady’s Morocco Oxford Lace’ (1887); ‘Boy’s Derby Balmoral’ boot (1887); ‘Lady’s calf kid Balmoral’ boot (1887); and ‘Lady’s patent calf Langtry tie shoe’ (1895).

Frank Clark in April 1876.

Meanwhile, Ireland proved vexing. Cyrus and James Clark had enjoyed considerable success in a country that, back in 1836, accounted for 30 per cent of footwear sales and 20 per cent of rug sales. In 1877, William looked long and hard at the Irish figures and was not pleased by what he saw. He estimated that his salesman was spending nine weeks a year in Ireland, dealing with wholesalers in Dublin, Cork, Belfast and Limerick, and that the return, once you had factored in various discounts, was lamentable. William wanted to go direct to the retailer, effectively cutting out the middle man.

In May 1878, he appointed a new, roving Irish agent, instructing him to offer a discount to retailers of 2.5 per cent on payment of a bill settled within three months, or 5 per cent if the bill was paid in cash. These arrangements were a great deal more favourable to Clarks than when dealing with Irish wholesalers, who often received discounts of as much as 10 per cent. But within weeks, William told his new recruit that he would not be renewing his contract once it expired at the end of three months. Sales had been poor and to make matters worse there was now no going back to the wholesalers whom he had sought to circumvent.

Three years later, in 1881, Frank Clark travelled to Ireland and hit upon the idea of working with J. & S. Allen, which employed a team of salesmen selling a wide range of general goods. On the understanding that J. & S. Allen would carry no other firm’s footwear, Frank offered Allen 5 per cent commission on sales. This didn’t work either and by early 1884, J. & S. Allen wanted to end the agreement. Initially, William was keen to persist with it, suggesting that Allen should have direct access to stock in Ireland, but then he came to the same sorry conclusion. In February 1884, he wrote to Allen confirming how things had:

… turned out just as we feared … and in consequence of giving you the agency we have entirely lost the custom of … 4 houses … who were, we believe, taking between them more of our goods than the total of your sales has since amounted to.

Later that year, it was agreed that yet another new salesman would cover Ireland, but that he would travel in the north of England as well and, crucially, he would sell rugs and fibre boards too. The result was not much better. Then, in 1890, Clarks came to an agreement with other footwear manufacturers – including A. Lovell and Co., in Bristol; Ward Bros, in Kettering; and Hanger and Chattaway, in Leicester – whereby a traveller would carry a full range of shoes from various manufacturers and the shoe companies would share the traveller’s customers.

Not long afterwards, William wrote to A. Lovell & Co. complaining that ‘we did not find the customers with whose names you furnished us generally such as we cared to open accounts with’. And in December 1891 he was telling Hanger and Chattaway that its goods were of inadequate quality to be shown alongside Clarks – and pulled out of that agreement too.

Elsewhere in the export market, caution was the policy, not least in Australia where Cyrus and James had enjoyed mixed fortunes in the past. Soon after he took control of the company, William wrote to Dalgety & Co., a firm of wholesalers in Melbourne, saying that he was considering sending new shipments to the country, but:

… the average results [in Australia] of the last few years have been so disastrous to us that on a principle that a burnt child dreads a fire, we are really afraid to take it up again.

Certainly, speculative shipments, which Cyrus and James had gone in for with disastrous consequences, were to be avoided, especially after the Australian legislature, keen to stimulate the home economy, voted in 1861 to impose tariffs on goods from outside the country. But in the 1870s and early 1880s Clarks made a push to secure big enough orders from Australian wholesalers to make it worth their while shouldering the burdens of shipping costs and customs duties. This slowly began to pay off, especially in Melbourne upon the appointment of an agent, Gavin Gibson. Even Sydney, which traditionally had not been a strong market for the Clarks, showed signs of life after a company called Enoch Taylor began acting on their behalf. In 1891, sales to Australia had reached £30,000, but these were followed by a worrying dip. Tension between agents – especially when the Clarks placed a greater emphasis on Victoria, South Australia and West Australia – combined with a limited range of footwear being offered to Australians saw sales plummet in the period 1893 to 1899. In fact, the years 1896, 1897 and 1898 showed no sales at all.

At one point, William’s worst fears were realised when he heard from an Australian retailer complaining how he was never shown any samples of ‘better class goods’. Clearly furious, William wrote to Enoch Taylor: ‘He [the retailer] says the same as others, that you people practically only offer the ankle straps and a few other lines in the Melbourne market’.

There were, however, encouraging results in South Africa. William sent a salesman called Walter Seymour to the country in 1885. His brief was to visit all major cities, offering customers a discount of 5 per cent. Seymour was also carrying goods made by Cave & Son, of Rushden, from which Clarks received a commission of 3.5 per cent. After a slow start, Seymour enjoyed some success and by 1889 was making two trips to South Africa per year.

A year later, in 1890, William’s eldest son, John Bright Clark, was diagnosed with tuberculosis. It was agreed that as part of his convalescence he would travel to South Africa. He arrived in Cape Town in September and it was not long before he had identified and hired a sole agent, E. C. Marklew, to represent Clarks in the whole of South Africa. Results were extraordinary. In 1891, Marklew achieved sales of just £43; a year later, that figure was £11,804 and in 1893 it had reached £16,099. By 1902, Marklew was shifting £46,551 worth of shoes, which was more than 30 per cent of C. & J. Clark’s total sales. This meant that in 1902 South Africa was C. & J. Clark’s strongest overseas market by some distance, followed by Australia and then New Zealand.

Sole agencies were now regarded as the way forward. In 1895, Max Vanstraaten was appointed the Clarks agent in France, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Holland, Belgium and Denmark. His company would receive 5 per cent commission on sales to retail outlets and 2.5 per cent on sales to wholesalers. Two years later, Oskar Wiener was hired on similar terms to look after South America.

T. P. Slim was taken on in New Zealand before, towards the end of the century, a man called John Angell Peck was appointed the sole agent in Australia and New Zealand. Peck became something of a role model for agents worldwide. Whereas sales in Australia and New Zealand in 1899 – the year of his appointment – were £3,948 in Australia and £213 in New Zealand, by 1903 they had reached £16,444 and £7,405 respectively. Peck remained in his post for 41 years, retiring in 1940.

A showcard for the home market in 1864 depicted a group of men and women playing croquet. ‘Manufacturers of most stylish and fashionable Ladies’ Boots’ was the strapline. Underneath, in smaller print, was added: ‘Every variety of gentlemen’s, ladies’ and children’s boots, shoes and slippers’. In other words, the Clarks considered that their business made shoes for everyone.

But competition, especially from America, was intensifying and it was important that C. & J. Clark should stand out from other UK shoemakers. Certainly, one of the company’s distinguishing features was its choice of fittings, something that had been pioneered and subsequently developed in the USA. As early as 1848, Clarks ladies’ ‘French shoes’ were offered in three fittings (N, M and W, referring to narrow, medium and wide) and in every size and half size from one to seven.

Then, in 1880, a further four new fittings (B, C, D and E) were launched. This emphasis on shoes that fitted properly and comfortably had a big influence on the launch in 1883 of the Hygienic range. The idea was to stress the importance of health rather than style. Hygienic boots and shoes came with the implicit backing of the medical profession. As a showcard said: ‘These boots do not deform the feet or cause corns and bunions but are comfortable to wear & make walking a pleasure’. Not perhaps the most sensual of recommendations, but sales were impressive none the less, with William declaring how the results had ‘exceeded our expectations’. The Hygienic range eventually became the Anatomical range.

New styles were developing – the first ‘ladies’ high-heeled shoes’ appeared in the 1877 price list – and strides were also being made with packaging and branding. The Tor trademark, so-named after Glastonbury Tor, the hill overlooking the town with St Michael’s tower at its summit, was immediately identified with C. & J. Clark, the word ‘Tor’ clearly visible on the soles.

![]()

Shoe-shopping today has for many people become a heightened retail experience. Fun. Daring. Therapeutic, even. And part of that experience is enlivened by packaging – the boxes, the tissue paper, the carrier bags. Clarks saw the importance of this as long ago as the 1880s, when for the first time a pair of shoes could be bought in a box, at an additional charge of one penny on cheaper lines, or free if the overall cost came to more than 6 shillings. Then, in 1893, C. & J. Clark created its own carton-making department and almost all its shoes could be bought in boxes at no extra cost.

Total sales of Clarks shoes in 1900 had reached £140,000, of which around 60 per cent was accounted for by the home market. And Street, once a small village through which people would pass on the way to Glastonbury or further west, was a thriving town of almost 4,000 inhabitants–thanks entirely to a tiny slipper business that had grown to become an international shoe giant.

![]()

In 1879, twelve months before the strike at C. & J. Clark, Eleanor, James’s wife, died. She had been ill for a number of years after suffering from congestion of the lungs. The final months of her life saw Eleanor mainly confined to the house and she was unable to go upstairs unaided. In summer, she would be taken in a pony carriage into the countryside, and James and she occasionally would stay a night with friends. Of his wife’s death, James recorded that:

… it pleased the Master to take my loved one to himself … words cannot convey an idea of the abiding sense of loneliness that has been my position … since the severance after nearly 45 years of union.

However, three years later in 1882, James married Sarah Brockbank Satterthwaite, the widow of Michael Satterthwaite, a former physician and schoolmaster. He and Sarah, who was seven years his junior, were both active in the Quaker ministry in Street and in the USA. ‘Heavenly Father had given her ten extra years of life to travel in America and another ten to marry James Clark’ wrote James’s grandson, Roger, in his journal dated 28 February 1903. By all accounts, James and Sarah spent 24 happy years together.

James became increasingly religious. Almost every morning at 7.30 am, he read the Bible at a small gathering of workers and in the course of one year during his retirement he made a point of visiting every Clarks employee in his or her own home. The Society of Friends’ Annual Monitor of 1907 spoke of James’s last few years as being a time when he ‘accepted cheerfully and without a murmur’ the restrictions of old age:

To the end, his interest was keen in all passing events in the village in which his long life had been spent, in the Society to whose welfare so much of his time had been devoted, and in the wider political life of the country. His cheerful spirit, and gratitude for every little attention, were much appreciated by his attendants. If, as occasionally happened, a certain impatience in his natural disposition found expression in words, the humble apologies he would quickly make to those about him affected them deeply.

On 28 December 1905, James woke early and said to his family:

I have given myself to the Lord tonight more entirely than I have ever done before, and he has promised me that His way shall be easy for me, and His burden light. And now I am wholly given up to the Lord.

A few weeks later, he started to weaken and on 15 January 1906, he said: ‘If I should pass away tonight tell William especially I have nothing of my own to look to, nothing to trust in, only in Jesus!’

He survived until the morning, when his family gathered around his bed. ‘I want to go to sleep’ he said. Half an hour later, he was dead, the end coming ‘so quietly that it was difficult to know when the gentle breathing ceased,’ recorded Roger Clark. James was 95 when he died.