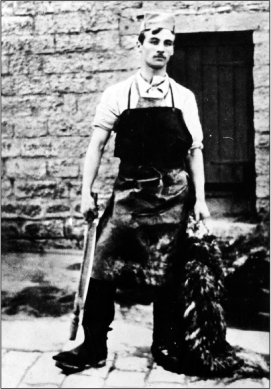

Roger Clark wearing apprentice’s working clothes at Clark, Son & Morland in Glastonbury in 1888.

‘OF COURSE I START WITH THE HEEL,’ said Manolo Blahnik, the Spanish fashion designer and High Priest of the stiletto, in a 2010 interview with Vogue. ‘Always! The heel is the most important part of the shoe, and the most difficult part. I have spent 35 years trying to make the perfect heel.’

In Street at the end of the nineteenth century, the debate was not so much about the height of heels as style versus comfort and the practicalities of combining both. Fashions were changing and younger members of the Clark family thought the company needed to move with the times. There was a danger of being left behind. For William S. Clark and his generation it was a case of coming to terms with the ‘Belle Epoque’ era, generally acknowledged as running from 1890 to 1914, when music, the arts and literature flourished, while the death of Queen Victoria in 1901 and the ascension to the throne of Edward VII was hastening the shift from Victorian formality to Edwardian frivolity. The new king enjoyed the company of women and was keen to see more of them. Hips became curvier, chests fuller, waists narrower.

Cometh the hour, cometh the much-celebrated hourglass figure, as bustles and heavy petticoats retreated into the sartorial distance. Women began joining men in the pursuit of leisure. They took up golf, croquet, fencing, riding and cycling – and needed to be shod accordingly. This called for an element of swagger to be introduced to the Clarks showcards, not least because America was stealing a march on many of its rivals in Britain.

Shoemakers on the other side of the Atlantic were experimenting in new, informal designs and offering them at temptingly low prices. Clarks was only too aware of this development because the company’s Quaker connections in America gathered intelligence to feed back to Somerset. This link with the United States was further strengthened in 1900 when Roger Clark, William’s second son, married a cousin, Sarah Bancroft, from Wilmington, Delaware, whom he had met during a sales tour of North America.

Roger had joined the company after leaving Bootham School in 1888 at the age of seventeen. At first, he worked in the counting house at Clark, Son & Morland, the rug business that was hived off from C. & J. Clark shortly after William took over as chairman. In 1890, Roger embarked upon two years studying dyeing and chemistry at the Victoria College in Leeds, but to little advantage because he suffered from severe eczema. Selling was one of his strengths and to this end he joined his brother, John Bright Clark, on a worldwide business tour in 1898.

John Bright Clark was four years older than Roger. He, too, had been educated at Bootham, returning to Street in 1884 after passing the London Matriculation Examination. He spent several years moving from one department at C. & J. Clark to another, including, at the age of nineteen, being taught the fundamentals of hand-sewn shoemaking from an outworker called Charles Maidment, who lived in Street’s Cranhill Road.

Both John Bright Clark and Roger Clark were dogged by poor health. Roger spent periods of his early life in Davos Platz in Switzerland and at Nordrach in the Black Forest, Germany. In fact, he was so impressed by the healing properties of Nordrach that he became a great supporter and benefactor of an English version of this health spa, which was set up near Charterhouse in the Mendip Hills.

Roger was ‘a sensitive man … with leanings towards socialism and a classless Christian ethic, who had to come to terms with his own position as a born capitalist’ according to Percy Lovell in Quaker Inheritance, 1871–1961. He was a great lover of Thomas Hardy novels, folk music, the William Morris arts and crafts movement, Pre-Raphaelite art, Gilbert and Sullivan musicals and the plays of Henrik Ibsen, all of which informed what Lovell called his ‘genuine concern for the poor and underprivileged’.

Roger Clark wearing apprentice’s working clothes at Clark, Son & Morland in Glastonbury in 1888.

It was hoped that John Bright’s and Roger’s trip abroad would be good for their health. They set out from Plymouth, calling in at Gibraltar, Marseilles and Naples, and then sailed through the Suez Canal. Roger spent a fortnight in Cairo, later joining up with John Bright in Adelaide before they both moved on to America. In September 1898, John Bright was called back to Street to help in the factory following a tragedy. Joseph Law, a well-regarded and highly talented foreman of the making and finishing departments, had died in an accident involving one of the factory lifts.

Roger, meanwhile, went on to stay with his cousins, the Bancrofts, in Delaware, which was where he met Sarah, and within weeks they were engaged. Such was the haste of their courtship that it was decided to keep the engagement a secret from everyone except close family for six months. And the wedding would not be for a further eighteen months.

Sarah’s father, William Bancroft, came from a family of Lancashire Quakers who had been successful in the cotton mill industry. They had emigrated to America in 1822, setting up a cotton manufacturing and finishing company in Rockford, Delaware, on the banks of the Brandywine river. In 1865, this business became known as Joseph Bancroft & Sons. William Bancroft’s younger brother, Samuel, was made president of the firm, but also took an active part in politics, first as a Republican, then a Democrat. An avid collector of art, in 1890 he bought his first Pre-Raphaelite painting, Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Water Willow, and went on to amass the biggest Pre-Raphaelite collection outside Britain. After his death in 1915, his family donated his paintings to the Wilmington Society of Fine Arts, which is now part of the Delaware Art Museum. Sarah’s mother, Emma, was also descended from English Quakers, but her ancestors had moved to America much earlier, in 1679.

Shortly before Roger asked Sarah to marry him, his mother wrote to his brother John Bright Clark and referred to a visit to England by the Bancrofts:

They are all very nice people. He [William] very good and sincere, rather a character, very simple and friendly though very prosperous … the two girls are very attractive.

After assessing his future son-in-law’s potential, William Bancroft suggested to Roger that he should stay in Delaware and join the Bancroft family firm rather than return to Clarks in Street, an offer that was politely declined. ‘They wanted me so much to go and live in America but I could not feel that that was the right place for me’ wrote Roger in a letter to his aunt, Priscilla Bright McLaren, on 11 May 1899.

But not taking the job meant returning to England and living on a separate continent from his 21-year-old fiancée. In twice-weekly letters, Roger and Sarah shared their hopes and aspirations, agreeing on the importance of education, the emancipation of women, the fight against racism and the so-called ‘new look’ of Quakerism, described graphically by Roger as a turning away from the ‘horrid old theory of sacrifice, substitution, propitiation, bargain-driving with Satan, and so forth’.

Their letters hinted at the challenges faced by the new generation of Clarks and how they would take the various businesses forward, while at the same time fulfilling their wider responsibilities to the community. But mainly the correspondence concentrated on a mutual desire to be together. Roger had already decided that he wanted them to live in Overleigh rather than Greenbank, William S. Clark’s former house, where he said they could get away with only one servant and establish a ‘really nice snug home’.

In a letter dated 27 April 1899, Roger wrote:

My own sweet love,

What a lovely letter thou has sent me. I cannot tell thee half the glad happiness it has brought me … I read it alone after tea. Thou must not be sorry thou wrote that other letter; I would rather by far have thee brought so close to me as I feel that thou has been, by letting me share in thy perplexities, as well as in thy certainties; for we shall always share them when they come to us, n’est ce pas? Thou hast always been far too good to me, sweet. I must keep in mind not to be spoiled.

That summer, Roger appeared to be getting in touch with his rustic side, telling Sarah:

I should like to take my bath always out of doors. It makes you feel so akin to the earth to stand naked on the grass with the delicious sun pouring down upon you; and after pouring the water all over me from as high as I could reach, my whole being seemed to give itself up to the simple enjoyment of the divine reaction and glow over body and limbs.

A couple of paragraphs later, he reverted to the more mundane topic of work and reflected again on William Bancroft’s job proposal:

I have been in the Boot Factory at a fresh job. I find it very hard to feel much satisfaction in taking up this new business; it is so complicated and full of detail. I am sure it would have been a fatal error to have attempted something similar in your mills at Rockford.

Sarah replied:

I should think the new business would worry thee. It would worry me dreadfully, even though I should like the learning, even the dull parts, but that too would weigh upon me when I thought of the wearisomeness of doing nothing else all one’s life … I wonder what the ambition of people who do such work can be. I should think it would kill all one’s ambition. And the moment one looks forward to some better work one begins to worry for fear one will not succeed. Oh, there are many difficulties along our pathways, aren’t there? But it is better so, of course.

The wedding eventually took place in the drawing room of the Bancroft family home in Rockford on 18 June 1900 and was attended by some 80 people. Roger’s parents, William and Helen, had sailed to America a few weeks before the ceremony, keen to see as much of the country as possible. In particular, Helen, as if doing the bidding of her reformist father, John Bright MP, ‘was always sniffing for evidence of colour prejudice and, not surprisingly, found ammunition in plenty’ according to Lovell.

Sarah did not find the transition from Delaware to Somerset always easy, but maintained close ties with her family, especially her sister Lucy, who also married an English Quaker, Dr Henry Gillett, and lived in Banbury Road, Oxford. Then, two years after setting up home together in Street, Roger and Sarah’s first child was born, a boy named William Bancroft Clark in deference to both the infant’s grandfathers. From an early age, he was known as Bancroft.

![]()

The infusion of young blood at the top of the company was encouraged by William S. Clark and formally acknowledged in 1903 when C. & J. Clark became a private limited liability company, with nominal capital of £160,000, preference shares of £100,000 and £60,000 ordinary shares. Five directors were appointed, all of them for life under the Articles of Association. William, who was now 64 and beginning to suffer from arthritis, remained as chairman and his co-directors were his brother, Frank, and three of his children, John Bright Clark, 36, Roger Clark, 32, and Alice Clark, 29.

Of the directors, Frank was the biggest shareholder with around 20,000 Ordinary shares, followed by William (with 18,000), John Bright (12,000), Roger (4,000) and Alice (3,000). The remaining shareholders were William’s three other daughters, Esther Clothier (1,000), Margaret Clark Gillett (1,000) and Hilda Clark (1,000).

Alice, who as a young girl had been sick with tuberculosis and who experienced poor health all through her life, joined the company in 1893 at the age of eighteen. She attended, briefly, a course in housewifery at Bristol, something that may have been lost on her given that she never married – although she was regarded as a great beauty – and went on to became an active campaigner for women’s suffrage. After four years learning how the factory operated, she went to work for Thomas Lugton, a Clarks agent in Edinburgh’s Princes Street, returning to Street as supervisor of the Machine Room. Later, she was responsible for the Trimming Room and the Turnshoe department, and was one of only a small group of women to reach a managerial position in industrial Britain at the start of the twentieth century.

The new, younger directors of what was now C. & J. Clark Ltd recognised that as a result of imports of cheaper footwear from America, many British manufacturers were turning their attention to what at the time was called the ‘better class trade’. Shoemakers throughout the country were determined to raise their collective game and were prepared to implement aggressive ways of increasing home production. How to attract a ‘better class of trade’ was a conundrum. It was William who, in 1897, came to the realisation that C. & J. Clark should forge closer ties with London’s fashionable West End, and at one point a suitably well-established shoemaker called A. McAfee was identified as a potential partner in the capital. McAfee was a bespoke shoemaker. The plan was that he would open a new shop selling shoes made by C. & J. Clark in addition to his own lines.

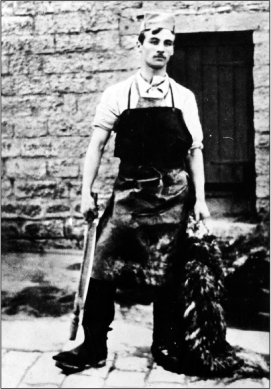

William S. Clark in May 1906.

In a letter to McAfee in June 1897, William was forthright:

The main inducement, in fact we might say the only inducement, from a business point of view … has been that we thought it would be an advantage to our general trade to be kept more closely and constantly in touch with the highest class of West End Trade.

To this end, C. & J. Clark would commit up to £3,000 on this joint venture, receiving a quarter of net profits. In effect – apart from a shop in Bridgwater, Somerset, that closed in 1864 – this represented the company’s first tentative foray into retailing. But it was not a path upon which William was setting off with any great relish and within months the partnership ended.

William S. Clark with his wife Helen and their children at Millfield, probably in the early 1900s. Standing, left to right: Roger, Margaret, John Bright and Alice. Sitting, left to right: Esther, Hilda, William and Helen with Fly the dog.

The issue of C. & J. Clark and retailing would persist for decades. In later years, there were family members who thought the firm should have opened its own shops a lot earlier, others who believed the company was right to stick to doing what it did best – manufacturing shoes. Writing to John Keats in 1898 following the McAfee episode, William told of his fear of upsetting existing outlets where Clarks shoes were sold and his concern about cutting out wholesalers who supplied the retail sector:

We are not at present prepared to cast all our present business to the winds and follow the example of Manfields and others in starting our own shops. The choice has to be between one and the other as if it got out that we were in any way going into the retail trade our present accounts would be closed. There is so much jealousy of these multiple shops.

George Barry Sutton wrote in C. & J. Clark, 1833–1903: A History of Shoemaking that the board wanted ‘time to see which way the cat would jump’ when it came to going down the retail path. The company was not alone in this. Most UK shoemakers operated in a similar way, selling via wholesalers or specialist shops. It was from foreign competition that the main threat came, with the Americans, in particular, making shoes and then selling them in Britain through specially opened shops.

In the same letter to Keats, William seemed to suggest that he was growing weary of the day-to-day stresses of running C. & J. Clark:

There is also the feeling as far as I am personally concerned, that I want as soon as I can see the chance, to get out of business altogether – as I have told you before I have done my share and now I am nearly 60 I want to get free and not to launch out in fresh extension and development.

In fact, he did not relinquish the reins of responsibility for a further 27 years, remaining chairman until 1925, by which time his arthritis had confined him to a wheelchair.

Responding to the new demands of fashion required nerve. The company produced a poster in 1905 that originated from America, showing an attractive women looking at herself in a full-length mirror. Dressed to impress, she was seen lifting up her long skirt and admiring her shoes, replete with high heels and pointed toes. This promotion for Clarks ‘Dainty’ shoes was successful in America, but was regarded as too risqué for the British market, although it was later pressed into service in Australia and the Far East.

Tapping into the American way of doing things took on a fresh impetus when John Walter Bostock joined the company in 1908. Bostock, who was born in 1873, came from Staffordshire. The Bostocks originally were from Heage, Derbyshire, moving to Stamford and then Northampton. Their connections with the shoe industry were even older than that of the Clarks. In 1759, Walter’s great-grandfather, William Bostock, was apprenticed to a shoemaker and it was his son, Thomas, who in 1814 set up a small business designing and making uppers, which he sent on to outworkers for them to attach the soles.

Public procession to mark the opening of the Street waterworks, heading along the High Street and past Crispin Hall on 18 June 1904.

Thomas Bostock had three sons, who went into partnership in 1840, naming the company Thomas Bostock & Sons, of which Lotus Ltd became a subsidiary in 1903. Lotus is today part of the Jacobson Group, whose brands include Gola, Ravel and Dunlop. In 1904, at the age of 31, John Walter Bostock, a grandson of Thomas, went to Boston, Massachusetts, to open up an agency selling, among other things, leather for uppers, and C. & J. Clark became one of his main customers.

Bostock was a moderniser. Throughout his career, he resisted the forces of conservatism and was credited with an ‘exhaustive knowledge of the shoemaker’s craft … inventive brain, lively imagination and unswerving determination to succeed,’ according to Clarks of Street, 1825–1950.

Frank Clark (at steering wheel) and Harry Bostock in a De Dion motor car, 1906. Harry Bostock was at this time the Clarks agent for New Zealand, and was instrumental in introducing his cousin, John Walter Bostock, to Clarks.

Bostock made a brief trip to Street in 1907 to show the management his glacé kid and upper leathers. ‘During this visit we were so impressed by his knowledge that we arranged for him to come over again,’ wrote Frank Clark’s son Hugh. He came to Street a second time in July 1908 and within a year had accepted a permanent job as production superintendent. This put him in charge of the pattern cutting, upper cuttings, closing, making, finishing, production of new lasts and sampling. A big brief, in other words. He was the first non-family member to occupy such a senior managerial role and went on to become a director in 1928, only retiring in 1946.

Company documents show that Bostock was given considerable authority and that he exercised it without threatening those who had come into the business by virtue of bearing the Clark name. His remuneration in 1909 amounted to a fixed salary of £750, plus 10 per cent of all profits above £8,000. A further 5 per cent would be added to profits between £12,000 and £16,000, and an additional 10 per cent on profits in excess of £20,000 a year.

Many of his responsibilities impinged on departments headed by members of the Clark family, but it was with Hugh Clark, Frank’s son, that he forged particularly strong links. Hugh had joined the company through the traditional route. After completing his education at Bootham and Leighton Park, a Quaker boarding school on the outskirts of Reading, he embarked on a four-year apprenticeship in 1904 at the age of seventeen. But finding a role for him was difficult, judging from a letter he received from his uncle, William, in June 1908 that spoke of securing:

… a more definite opening … to give … the opportunity of being of some real service in the business after … rather wearisome years of preparation for it.

In fact, Hugh went on to occupy a number of senior positions, while also serving as a captain in the First World War, during which he was awarded the Military Cross for evacuating a French town under enemy fire. His first main role at C. & J. Clark was overseeing the building, engineering and electricians department. Later, he succeeded John Bright Clark as head of sales and was influential in the company’s first forays into retailing.

Another influential figure singled out for high office was Wilfrid George Hinde, who was thirteen years older than Bostock and a grandson of James Clark. Hinde joined the firm in 1910 to work under John Bright Clark in the costings department and had special responsibilities for developing the ‘factory system’. To this end, he was sent in 1912 to America, where he visited several shoe factories including J. Edwards & Company in Philadelphia, which specialised in high-grade children’s shoes. This factory was managed by a man called Parrott, who happened to come from Somerset and was only too pleased to share his carefully defined work practices with young Hinde.

Parrott had made factory systems his hobby and was renowned for his production timetables, which Hinde then adapted for use at Street. This marked a new departure for the company. Until then, orders went through the factory in rotation, but there was no daily or weekly timetable for each department. When it came to costings, Hinde was meticulous. On one occasion he was even keen to know how much money had been spent repairing Frank Clark’s Daimler, prompting Frank to remind him that any work on the car was entirely due to it being used to transport customers to and from Glastonbury train station.

Hugh Clark (at left) at the Friends’ Ambulance Unit in 1915, with his father Frank Clark’s Bianchi after conversion into an ambulance.

Hinde, whose brother Karl also worked at C. & J. Clark, was seen as a man of many talents. In addition to costings and factory systems, he was instrumental in introducing ‘standard lines’, which in the 1920s would lead to the first mass production of shoes – footwear using high-quality materials but not requiring so many man-hours. Hinde also saw the value of advertising, eventually working on C. & J. Clark’s first campaign devised by the Arundel Advertising Company.

Like Bostock, Hinde – who had spent time in prison as a conscientious objector in 1916 – was appointed a director in 1928 and remained with the company until 1947. Non-family members found it hard to reach such exalted positions. Richard Wallis Littleboy, who hailed from Birmingham, was one exception. He joined in 1904 and was put in charge of accounts, but was soon given additional responsibilities, not least the organisation of salaried staff. It was not long before he was a signatory on company cheques and he, too, was given a percentage share of profits.

Bostock was keen for other non-family members to secure similar promotions, but there was often resistance. In May 1911, he pushed for a man called William Wells to be made manager of the Machine Room, but the minutes of a directors’ meeting noted that while there were:

… great advantages in giving promotion to those who have grown up in the Factory … grave doubts [existed] as to whether he [Wells] has sufficient tact and organising power to handle a department containing 300 women and girls.

So Hugh Clark was given the job instead and Wells became his foreman.

![]()

The company was proud of its American influences. The 1906 Tor Shoes Catalogue trumpeted:

… the newest and best, the lasts and patterns having been perfected in the United States by the highest American skill procurable for money, care having been taken that the shapes should be exactly adapted to the requirements of our market.

But there were dissenting voices within Clarks about the speed of change and the pursuit of style, especially when it came to breaking into the fashionable London market.

One of the problems in London was that as a sales territory it was split between the regions – the Midlands, the South East and even the North – and served by dedicated travelling salesmen, who worked for a straight salary, plus expenses, and who were offered bonuses in good years. The travelling salesmen were held in high esteem, but there was disagreement between them and the board over commission. ‘We do not work any of our home grounds by giving commission – we do not think it a satisfactory arrangement’, said a 1908 directors’ minute.

A year earlier, John Angell Peck, who had been so successful as an agent in Australia, was invited to Street to ‘supervise the travellers’, although the board noted that he was not enamoured of the prospect. Peck, keen for Clarks shoes to become more fashionable, insisted on setting up a dedicated showroom in London, and by January 1908 he found the premises he was looking for in Shaftesbury Avenue, on the corner of Soho’s Dean Street. It would cost £130 a year in rent.

‘When in London be sure to call at our Office and Showroom’ said a leaflet sent to wholesalers, with a complicated map printed on it. Peck himself did not stay in London long, returning to Australia less than two years later. He was replaced by John Downes, a former buyer from Jones & Higgins, the noted department store on Peckham High Street, which had opened in 1867. Downes was offered a salary of £250 per annum, with commission of 1 per cent on any increase in turnover. The commission floodgates had opened and it was to prove a lucrative pool for all concerned, so lucrative in fact that in 1918 the board wanted to cap earnings, noting that some travellers were making more ‘than any director of the company has ever drawn’.

Agents overseas, however, were enjoying mixed fortunes. Results in South Africa continued to be encouraging, with trade reaching £48,000 in 1910, compared with £28,052 in 1895, but South America proved more taxing. Peck travelled to Buenos Aires to discuss trade with Clarks’ representative, Alex Zoccola, but the situation there was not helped when a partner of Zoccola’s absconded with money. At one point, in 1911, the board noted that ‘after many thefts – unreasonable claims – and difficulties in turning out the right stuff … [it was decided] a mistake was made in ever going into it’. In fact, Clarks persisted in South America, as it did elsewhere, even sending a senior agent to Russia and Siberia to explore potential new markets.

The French were proving tricky. Or, rather, it was proving difficult to produce shoes that the French were willing to buy. Edmund Skepper became C. & J. Clark’s agent in France and he was supplied with specially designed samples to entice retailers. An advertising campaign was launched, talking up the Clark name and pushing the Tor brand, but at a managers’ meeting in 1911 there was concern about ‘future trouble with other houses if we made a big success of the [French] advertising’. Those concerns cannot have been too great because a year later Skepper received new lines worth £1,500, with a further £1,500 of stock heading his way.

At first, sales in France picked up, but then Skepper asked if his retailers could be given 30 per cent discounts, with an extra 2 per cent on orders of more than three dozen pairs. By 13 July 1913, the board was told that Skepper ‘reluctantly came to the conclusion he could not make a success of it’.

Elsewhere in Europe, agencies in Germany and Switzerland were increasing their turnovers and the market in Finland was growing. New agents were sought for Austria, Belgium and Holland, and, further afield, Joseph Law, who would later head Clarks’ operations in India and the Far East, was sent to Burma (now Myanmar), Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Java, India, Siam (now Thailand) and Sumatra.

Shortly before the First World War, The Economist published an article entitled ‘The Victory of British Boots’, in which it took British shoemakers to task:

It was a surprising number of years before our makers woke up to the necessity of bestirring themselves … they found that the secret of Yankee success lay entirely in style and finish, and on returning they set to work to imitate their competitors in those respects … the significant fact should not be lost sight of that the great bulk of the improvement has occurred in the last five years, and when it is borne in mind that for 1912 the exports were worth very nearly 4 millions sterling, some conception can be formed of the splendid possibilities before the trade in the immediate future.

A parade in support of women’s suffrage outside Crispin Hall, Street, in 1913. Alice Clark, one of only a small number of women to reach a managerial position in industry at the time, was an active campaigner for the women’s suffrage movement.

The war would take its toll in Street. Unlike shoe manufacturers in Northampton and Leicester, C. & J. Clark failed to gain a share of government orders for soldiers’ boots. Overseas sales suffered badly to the extent that by the end of the war – when C. & J Clark was producing a million pairs of shoes – a mere 100,000 of these were destined for export and it took nearly three decades for exports to double, reaching 200,000 pairs only in 1947. Overall, total volume sales fell dramatically from a 1914 peak of 1,013,000 to 541,000 in 1921.

William S. Clark remained chairman during the war years, but the two joint managing directors – his brother, Frank, and his eldest son, John Bright – took increasing charge. Meanwhile, Roger, William’s second son, became the company secretary and Alice, William’s daughter, was responsible for Personnel Management and the Closing Room.

Semi-retirement for William was filled with onerous duties outside the factory. From 1878 to 1922, he served continuously as a member of the Local Authority, sixteen of those years on the Local Board and 28 on the Urban District Council. And most of that time, he was chairman of both bodies, only relinquishing his post at the age of 83. On standing down from the council, he was praised for his enduring sense of duty. The citation read:

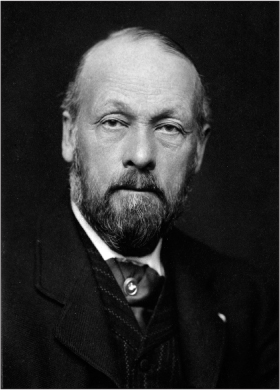

William Sessions, an outworker in Street, photographed at work around 1917.

We are grateful for all the recollections that we cherish of your public spirit, unfailing courtesy and kindness … We remember your fearless advocacy of all you believed to be true and right. You never sought a fleeting popularity by disguising your principles, you gave freely and fully of your experience, and the fruit of your sound judgment and keen business acumen to the moulding and fashioning of the life and character of the Institutions of Street.

William had been a Justice of the Peace, president of the Glastonbury and Street branch of the British and Foreign Bible Society, treasurer of the Western Temperance League, Fellow of the Royal Meteorological Society, long-time member of the Somerset Archeological Society (now the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society) and a governor of various schools. He had also developed a passion for poetry. Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene, the first volume of which was published in 1590, was a particular favourite. He carried many of its verses in his head and used to recite them to his children when they were young.

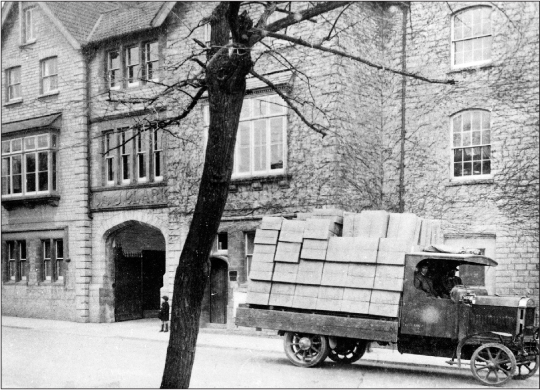

A Dennis lorry used for transporting goods around the factory site and for regular runs as a charabanc to Glastonbury railway station, seen outside the main entrance to the Street factory around 1920.

William was regarded as a good communicator. Doubtless he would have approved of the formation, in 1919, of a Factory Committee or Factory Council or Works Council, as it variously was called. This in-house council comprised a combination of workers and management and its aim was to deal with grievances and consider any suggestions from the factory floor. In particular, it would come into its own during the depression years of the 1920s and 1930s, when work-sharing was introduced to avoid widespread unemployment. Further support for employees came in the form of clubs, such as the Street Shoemakers’ Benefit Society, Street Women’s Benefit Society and Street Women’s Club. These organisations joined forces in 1913 to become the Street Shoemakers’ Provident Benefit Society, which led to the founding in 1918 of a C. J. C. Savings Bank, which used its surplus (profit) to make payments to members who were sick or retired.

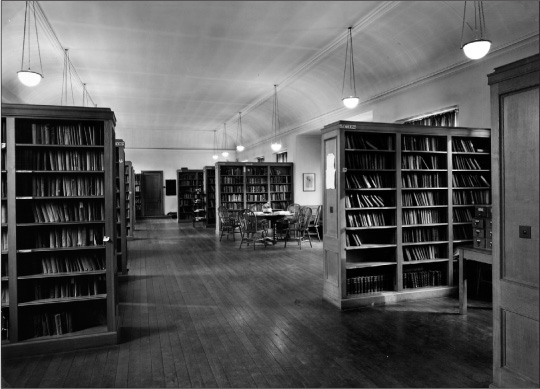

Interior of the library, designed by Samuel Thompson Clothier and paid for by the Clark family, built in Street in 1924 and seen here in 1949.

Several years later in 1924, C. & J. Clark began circulating its Monthly News Sheet as a means of communicating directly with the workforce. The first issue, in August, made a point of stressing that the publication had come about at ‘the request of the new factory committee’ and that it would include ‘items of news likely to be of general interest to those working in the factory’.

That same year, a new library in Street, funded entirely by C. & J. Clark and designed by William S. Clark’s son-in-law, Samuel Thompson Clothier (known as Tom), who designed many civic buildings in Street, was officially opened by Charles Trevelyan MP, who had recently been appointed President of the Board of Education by Ramsay Macdonald, the prime minister who led the Independent Labour Party to victory in the 1924 General Election.

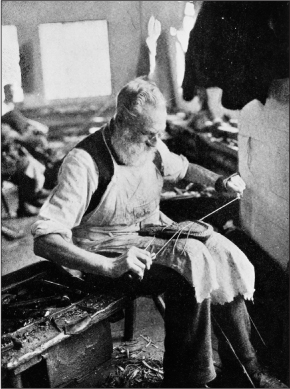

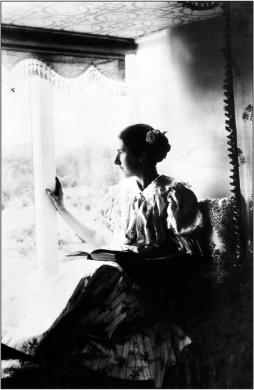

Alice Clark as a young woman in 1895.

One of the loudest voices in favour of better worker welfare was that of William’s daughter, Alice Clark. In 1914, she played a key role in setting up the Day Continuation School in Street, to which the company contributed half the costs. The school was intended expressly for boys and girls who had abandoned their education at the age of fourteen to work in the factory. Pupils would attend one morning and one afternoon a week. Alice, a resolute feminist, was thrilled at the prospect of young girls attending continuation school. She had been present, aged seventeen, at the formation of the Street Women’s Liberal Association and served as its secretary for eleven years. She sat on the executive of the Union of Suffrage Societies, which meant she spent a lot of time in London meeting and cajoling MPs, for which she had the full support of her family and fellow board members in Street. Alice also served as chairman of the committee responsible for Quaker relief work in Austria at the end of the First World War.

At a meeting of the directors of C. & J. Clark in 1914, it was agreed that ‘the possibility of arranging to let out children from 14 to 16 or 17 during Factory hours to attend classes was … discussed and felt to be desirable’. This was conducted on an ad hoc basis, particularly during the First World War, when:

… it had sometimes been necessary to keep one or two away from the afternoon school, labour shortages prompting the suggestion that Mr Alexander the School Master might, weed out … some of the older ones, especially any who do not care about school, or who are troublesome in discipline.

But sanctioning boys and girls to miss school was not something the board wished to encourage. It ‘should not be a precedent to be resorted to easily again,’ it concluded.

After the war, weekly attendance was increased to eight hours, or two half days per week for each pupil. This was in sharp contrast to what was happening nationally, despite the Education Act of 1918, which raised the school leaving age from twelve to fourteen and offered some form of continuation classes. In reality, many authorities, short of cash, were cutting back on education, leaving continuation schools solely in the hands of private companies. In 1921, a full-time qualified headmistress named Annie Bent was appointed to the Strode Day Continuation School, as the school had then become, and she was joined four years later in 1925 by a headmaster called William Boyd Henderson, known as Boyd Henderson.

Marvelling over the circumstances contributing to his employment, Boyd Henderson referred to there being:

… no advertising; no scanning of testimonials; no interview with the Governors. The fact that I was Millicent Falk’s [a mutual friend of Henderson and Alice Clark] cousin seemed to be all the testimonial that was needed, and on that recommendation I was appointed.

In fact, Alice had been instrumental in the choosing of Boyd Henderson, believing that he shared many of her ideas and that he would embrace the school’s liberal ethos.

His arrival was accompanied in 1926 by the adoption of the half-time system of twenty hours per week, which meant that if two children shared a job, one would be working in the factory while the other went to school. Pupils included workers from Clark, Son & Morland after 1926, in addition to those employed by C. & J. Clark.

As Roger Clark wrote in the foreword of William Boyd Henderson’s Strode School, a short history of the school:

It was always the aim of W. S. Clark, of Alice Clark and of those following them that the school should never be a mere technical adjunct of the Factory, but rather that the children who left school at fourteen to enter the Factory should acquire a richer mental background, a wider culture, such as would serve through life to stimulate the intellectual powers and an interest in things worthwhile.

Henderson himself was passionate about the school’s mission:

They [the pupils] are engaged in industry but yet they are continuing their education. But there is more than that. Entry in industrial life at whatever age it takes place is a revolutionary change in the lives of boys and girls. Previously they have been at a whole-time school mixing with companions of their own age. Now they are in a factory mixing with men and women. Previously they have been dependent on their parents for pocket money. Now they are wage earners whose pay packet makes a considerable difference to the weekly family budget.

Alice Clark’s interest in what her brother Roger called ‘things worthwhile’ included writing a book, published in 1919, entitled Working Life of Women in the Seventeenth Century, which is still highly regarded today and was the subject of a discussion on BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour in 1998. It was based on the premise that British women, especially those from the middle and upper classes, were more independent and therefore more liberated in the seventeenth century than they were in the nineteenth.

It was while working on her book that Alice was awarded the Mrs Bernard Shaw Scholarship to study at the London School of Economics. When she returned from London to Street in January 1922, she threw herself into her job, making the personnel management department a model for everything she felt important about factory life. She organised a system of records for each employee to ensure they were in the right job and adequately fulfilled in what they were doing. She checked the earnings of each worker and played a key role in setting up a company pension plan, with a trust to protect it. The pension scheme was launched in 1926 with £15,000 assigned for this purpose, with a further £10,000 added shortly afterwards. Over the next twenty years the capital would exceed £100,000.

Alice was absent from C. & J. Clark for long periods due to illness, a legacy of her childhood tuberculosis, and she became an increasingly ardent supporter of the Christian Science movement. ‘The problem of evil, which the War had made more terrible than ever, was lying on her mind; and there was also her personal trouble of being several times disabled by illness’ wrote her sister, Margaret Clark Gillett, in a special obituary pamphlet published by Oxford University Press shortly after Alice died.

On both these lines she came to find an explanation which satisfied her in the doctrine of the Christian Science Church. The doctrine helped her; she felt herself liberated; she gained the experience of rising over what was threatening to conquer her. Thus she was enabled to bring light and courage to many others.

The article also sought to sum up Alice’s thinking about the dispersal of company profits:

She came to feel more and more strongly that a business should be run and profits apportioned for the benefit of all concerned in it. She saw that this would involve a limit being set to the rate of interest paid to shareholders on their capital, and she realised that there would be great difficulty in rendering such a limitation effective, but she believed that a solution of this difficulty is essential if we are to find our way to juster [sic] social order.

Greenbank Pool, built at the wish of Alice Clark and paid for from her estate, primarily for the benefit of female bathers, seen here from the roof of the new post office on Whit Sunday, 1963.

Towards the end of her life, Alice resigned her Quaker membership, but she was often heard to declare how she ‘could not swallow Mary Baker Eddy [founder of the Christian Scientists] whole’. Family members were sorry to learn of her religious defection, but Roger remained in awe of his sister’s personality. In a letter to his mother-in-law, Emma Bancroft, in January 1927, he spoke of Alice’s ‘sweetness and calm’, adding:

I don’t know just what Christian Science can do for the body, but if it deserves any of the credit for Alice’s spiritual poise and character it must have something in it …

When Alice died at the age of 60, on 11 May 1934, she left a legacy to her youngest sister, Hilda, and also expressed a wish that a swimming pool be built in Street, primarily to be used by women and young girls, who were loathe to join their male counterparts bathing in the river, often naked. She set aside a gift of £5,000 for this purpose. Hilda fulfilled her sister’s wish and the pool opened for business on 1 May 1937, attracting more than 36,000 people in its first summer. The annual subscription was 2s. for those over nineteen and 1s. for those under nineteen, with an entrance fee ranging from 2d. to 6d. a visit. It became known as Greenbank Pool, after the Clark family home of the same name, and remains a popular outdoor pool and public space today.

![]()

The Roaring Twenties heralded a new dawn for luxury and fashion goods, but among the majority of consumers there was no great appetite for spending hard-earned money on everyday shoes, even when the quality was high. The management of C. & J. Clark was only too aware of the problem, but not entirely sure how to remedy it.

John Bright Clark was open with the workers about what he saw as some of the pressing issues facing the new generation of management. Writing in the first issue of the Monthly News Sheet in August 1924, he said C. & J. Clark was proud of its high-quality Tor brands, but:

… unfortunately there is a limit to the demand for goods of the Tor brand standard in this country, and it must take a long time for it to increase enough to cover our capacity for output. The management are considering the possibility of introducing a cheaper grade of ladies’ shoe to meet the public demand.

He went on to highlight the downside of this strategy and then did his best to end on an optimistic note:

Competition for these lower grades is very keen and it may prove impossible to meet it in a factory burdened with the costs necessary for the present high grade of production. The management are exploring every possibility of reducing costs by mass-production and other ways, so as to secure some large business on these lines, but they cannot as yet say whether their efforts will be successful. It is not proposed to make any lines that will not do us credit or give reasonable satisfaction, but care will have to be taken to keep them distinct from existing lines, so that business done on them may be extra and not in the place of what we might otherwise be doing. For this reason, these lines will not carry the Tor brand trade mark and we shall endeavour to keep the design distinct and use different grades of upper material.

Trepidation was in the air. And, as if to compound the anxiety, William S. Clark had a massive heart attack in August 1925, from which he would never recover. Unable to walk more than one or two steps without help, he spent the last months of his life in bed or in an armchair. On the morning of 20 November 1925, he appeared more engaged than he had been for several days, asking his son, Roger, for details of the new Club and Institute Committee, of which William had been re-elected president the day before. He was also keen to know of any developments at the latest meeting of the Western Temperance League Executive.

William died later that morning in what was the centenary year of the founding of C. & J. Clark. He was 86. A flag was run up a pole on top of the clock tower at the factory and flown at half mast. The announcement about his funeral, scheduled for three days later, included two verses from Spenser’s Faerie Queene, beginning with William’s favourite opening line: ‘And is there care in Heaven?’ His widow, Helen, who followed the cortège in a wheelchair, wanted a band to lead the procession, but not just any band. She chose the local Street Prize Band, which played Chopin’s ‘Funeral March’.

The turn-out in honour of the man described by the Central Somerset Gazette as ‘the father of the town’ was like nothing seen before in Street – or since. One published account said:

The usually busy village was full of silent waiting crowds, no throb of engines from the factory, shops shut, blinds drawn, men, women and children waited in the slant November sunshine as if for a royal procession.

Roger Clark wrote how it was:

… a grey soft afternoon with gleams of sun and the music quite extraordinarily beautiful and moving and it had a wonderful uniting effect on all that long procession – of which one could not at any time see the end.

The service was held at the Society of Friends’ meeting house at 3 pm and he was laid to rest in the burial ground beneath the boughs of a huge cedar tree, his grave framed by white chrysanthemums and roses. As his oak coffin – with several wreaths on top of it, including one from the Factory Council – was lowered into the ground, the hymn ‘Abide With Me’ was sung.

From there, the band struck up once more, playing Beethoven’s Funeral March, and the crowd made its way to Crispin Hall, where a thousand people managed to squeeze into the main hall, with many others waiting outside. Dr Henry Gillett, a cousin from Oxford, explained that the service would follow Quaker traditions: ‘At a time like this when a Friend is missed from among us we recognise that there is strength in silence, communion of sympathy, deeper than words.’

But there were words. Speaker after speaker testified to William’s great strengths, the manner in which he had saved C. & J Clark and how he had built an entire town around the family business. Before the singing of ‘O God, Our Help in Ages Past’, John Morland, who was 88, rose to his feet. He was William’s brother-in-law and a lifelong friend from their school days. The room fell silent as he prepared his words.

A life such as we have known is one of the best witnesses for resurrection to immortal life that we can have. It is impossible for those who loved him and saw what he did to believe that such a life can pass away into nothingness.