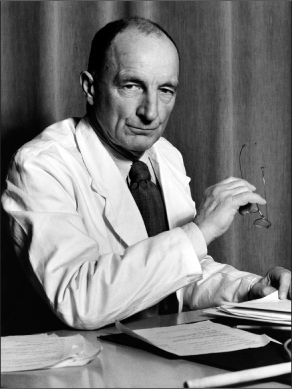

Bancroft Clark, chairman from 1942 to 1967.

IN THE YEARS that followed the Second World War, Britain was to change beyond recognition – but not immediately. As the country celebrated the end of warfare and the beginnings of wide-reaching reform under a victorious Labour government, the cultural and economic landscape in 1945 was far from fertile. Making do was the edict of the day.

As David Kynaston described in Austerity Britain, 1945–51, there were:

… no supermarkets, no motorways, no teabags, no sliced bread, no frozen food, no flavoured crisps, no lager, no microwaves, no dishwashers, no Formica … Central heating rare, coke boilers, water geysers, the coal fire, the hearth, the home, chilblains common … White faces everywhere. Back-to-backs, narrow cobbled streets, Victorian terraces, no high-rises. Arterial roads, suburban semis, the march of the pylon. Austin Sevens, Ford Eights, no seat belts, Triumph motorcycles with sidecars. A Bakelite wireless in the home, Housewives Choice or Workers Playtime or ITMA on the air, televisions almost unknown … Milk of Magnesia, Vick Vapour Rub, Friars Balsam, Fynnon Salts, Eno’s, Germolene. Suits and hats, dresses and hats, cloth caps and mufflers, no leisurewear, no teenagers. Heavy coins, heavy shoes, heavy suitcases, heavy tweed coats, heavy leather footballs, no unbearable lightness of being. Meat rationed, tea rationed, cheese rationed, jam rationed, eggs rationed, sweets rationed, soap rationed, clothes rationed.

Within a year of VE Day, disgruntlement was seeping into the system. The Sunday Pictorial, sister paper of the left-leaning Daily Mirror – and one of several publications in which Clarks shoes were advertised – launched a ’100 Families to Speak for Britain’ campaign, in which readers were invited to get their grievances off their chests and on to the national agenda. One woman, Eileen Lewis, from Croxley Green in Hertfordshire, told the newspaper: ‘I can’t get shoes for my kiddies. A couple of weeks ago I spent all day trying to buy two pairs of shoes. I must have called at twenty shops’.

Mrs Lewis’s frustration would have found sympathy in Street, where a contributor to the first issue of Clarks Comments, a new in-house publication for staff, retailers and suppliers, railed against ongoing wartime restrictions. The unnamed contributor was particularly exercised by the:

… absurd regulation which prevents a shoe manufacturer from saving materials and making open ventilated sandals. In America, they have been wiser than we in this respect, and have allowed the manufacture of ventilated shoes; indeed, half the shoes women wear today are toeless and heel-less … Women’s shoe styles in America are now blossoming out again. During the five years of relative separation, they have made considerable changes. Their lasts are broader in the tread, shorter in the forepart length and bigger in the joint measure.

Shoemakers had often looked enviously at their counterparts across the Atlantic both in the context of styling and technical breakthroughs. In the 1940s, Americans had developed the ‘slip-lasted’ shoe method, often referred to as the California Last construction. This required no stiff insole board. With a slip-lasted shoe, the upper materials were stitched to a fabric sock. The last was then forced into the shoe, the platform cover neatly wrapped over a lightweight flexible board and the sole attached in the traditional way. This process created more flexible and therefore more comfortable shoes, though they coped less well in wet conditions.

In Britain, people tended to walk more than they did in America, where, by 1946, the motorcar was a common feature of post-war life. But even so – and much to the chagrin of Bancroft Clark – Americans were presented with a far wider choice of what to wear on their feet and were buying twice as many shoes per head as the British.

To find out why, Bancroft dispatched Tony Clark to America in April 1946, along with Leslie Graves, a factory manager with proven production and design skills, and two other heads of department, one in charge of last and wooden heel-making, the other responsible for pattern cutting. They visited New York, Boston, St Louis, Cincinnati and Buffalo, where they inspected the maple trees from which the Clarks last-making blocks were cut. The trip resulted in a stark observation: ‘The chief impression, which we brought back about shoemaking was the great superiority of American machinery over ours,’ wrote Tony Clark in Clarks Comments. He continued:

Here, we are suffering badly after six years of war through having to operate worn-out and obsolete machinery which we cannot even get repaired satisfactorily, let alone replaced by new and improved types … The type of machine they are using [in America] is in many ways more efficient and up-to-date than ours. We saw in every department machines which we need badly and which, if we had them, would lead to an immediate improvement in the quality of our shoes and also to increased output.

Bancroft had travelled to America himself immediately after the war and was convinced that despite continued rationing and other impediments to the growth of the UK economy, the shoe trade was ripe for expansion. He predicted that if employment picked up and foreign trade treaties were reformed, shoe manufacturing would be set fair. Crucially, he recognised that if buying power became stronger it would be women doing the spending:

Women will want to feel neat, trim, smart and lovely … Their outward appearance will be an expansion of and a cause of their inner well-being … Women will want more clothes and that includes shoes. With a shorter working week they will have time to think about nice clothes and [have] more time to wear them … Shoe style is not merely upper colour and decoration. One of the most important elements in women’s style will be fit. A shoe that does not fit and does not keep its fit will slop, lengthen, gape, bag, wrinkle. Whatever eye appeal it may have in the window, it will not be style on the foot. What women will want to buy, what they will be educated to buy, will be style on the foot.

Bancroft was convinced of the urgent need to widen Clarks’ production capabilities, something that had been tried and tested several years earlier in 1938 when the company entered into a formal and successful arrangement with John Halliday & Son to make shoes in Ireland. Halliday was a former Leeds manufacturing firm founded in 1868, specialising in heavy agricultural boots. In 1928, it closed down in the north of England and opened up in Ireland after buying an old cholera hospital in Dundalk, County Louth. But, hindered by the decline of Irish farming and the new-found popularity of the Wellington boot, it struggled. Arthur Halliday, the company’s managing director, needed to diversify and was approached by four different companies: Padmore & Barnes, Lotus, Somervell, which made K Shoes, and C. & J. Clark. Halliday was educated at the Quaker Bootham School in York and it must have been clear almost immediately that he would slip seamlessly into the Clarks culture – and so it proved. Once the deal had been signed, Bancroft wrote that Arthur Halliday was ‘our strongest card … [who] likes to have our support against the Wild Irish who are his workers, staff and directors’.

A five-year contract was drawn up between C. & J. Clark and John Halliday & Son, and a new subsidiary, Clarks Ireland Ltd, was formed. Initially, the Irish operation made only women’s shoes, but within a year it had moved into children’s footwear. The contract was extended in 1943 and by 1948 Halliday’s was producing 500,000 pairs of Clarks shoes a year.

Such was the importance of the Irish market that Arthur Halliday joined the board of C. & J. Clark Ltd on 1 January 1947, shortly after John Walter Bostock retired and a few months before Wilfrid Hinde stood down, both big characters who had enjoyed starring roles in the company in the first half of the twentieth century. Meanwhile, H. Brooking Clark, son of Hugh Clark, joined the company after leaving Oxford university and serving as an officer in the Scots Guards in North Africa. Brooking would be invited on to the board in 1952 and later became company secretary before leaving C. & J. Clark in 1965.

Bancroft Clark, chairman from 1942 to 1967.

During the war, owing to a lack of space in Street, Clarks had opened a closing room in St John Street, Bridgwater, to machine-finish the uppers of shoes for the armed forces and then, after the war, to make demobilisation footwear. This led to the launch of a full-scale factory in Bridgwater in June 1945 when Clarks exchanged contracts on a former dairy, where the emphasis was on developing the slip-lasting process that had proved so successful in America. In time, the factory was enlarged with the construction of a new building in the dairy yard that had become a recreational area for employees. The women workers lost their netball pitch but Clarks gained a valuable making room, where local unskilled labour was trained by teams sent from Street to Bridgwater each morning.

A second factory was opened in Shepton Mallet, built on the site of Summerleaze park, where American forces had been based during the war. On taking possession of it in June 1946, Clarks acquired eight double Romney huts, which had been used as aircraft hangars and then warehouses. A mere seven days after being granted a licence by the Ministry of Works, the huts were converted and production of ‘Infants Playe-ups Sandals’ (known shortly afterwards as ‘Play-ups’) began.

Bancroft Clark had long been a believer in decentralisation and pursued it like a man on a mission. Several years earlier, following a visit to Bally in Switzerland, he had reported seeing:

… factories scattered about in different villages so that they do not get either too many people living close together, or too large a proportion of their workpeople coming long distances.

In 1945, he outlined his overall strategy, talking about how the new additional factories would ‘take the lid off people’ with ‘each main unit … separately managed by a manager of potential directorial status’.

The Shepton Mallet factory was managed by A. William (Bill) Graves, the younger brother of the production expert Leslie Graves, who had been responsible for the factory in Bridgwater. Shepton Mallet employed ten women and eight men and in its first week produced 200 infants’ Play-ups – all of which turned out to be sub-standard. There was no disguising this from Bancroft when he visited at the end of that week. The chairman expressed his displeasure, after which Graves made sure that any deficiencies in the system were ironed out, and by the end of 1946 the factory was making 1,000 pairs a week. A year later, Number Two Factory, as it was called, opened on the Shepton Mallet site, followed closely by Number Three Factory. In 1953, the UK Shoe Research Association declared the Shepton Mallet factories the most efficient in the country, and Graves went on to open a further eight factories in the West Country.

In Bridgwater, a new building at Redgate Farm, to be known as the Redgate factory, opened in January 1947, covering 20,000 sq ft and costing £20,500. Here, within twelve months, a highly efficient mass-production capability boosted output to 4,650 pairs a week, mainly of women’s casual shoes, particularly ‘Clippers’, which were advertised as ‘Clippers in gay colours for playtime’.

It had been a swashbuckling start to peacetime trading. Sales in 1946 were up 28 per cent on 1945, with profits rising by 23 per cent, a result that may not have come as a surprise given that Clarks was one of only a few companies which managed to maintain their output during the war. The firm produced 70 per cent more shoes in 1946 than it did in 1935 and for the first time it was making the same proportion of women’s and children’s footwear. This growth would continue at an even faster rate. Clarks made 1.25 million pairs in 1946, rising to an astonishing 2 million in 1948, and in terms of personnel, by the end of the year there were close to 2,000 men and women working across all the Clarks factories.

Bancroft was not sitting in his chairman’s chair with any sense of complacency, however. In the 1946 annual Directors Report and Accounts – which was read only by senior members of the company – he was quick to point out that government subsidies to tanners for help with the cost of hides and skins had created an ‘artificial position’ and therefore he was revising down his forecasts for the coming year. He also took the opportunity to make some critical observations about the workforce: ‘a certain laxness in time-keeping … [and] difficulty in getting new employees to reach the speed of output required in a competitive shoe industry.’ Things had not improved greatly a year later: ‘Our only grumble with our employees is a certain slackness about time-keeping’ he told the directors. ‘Our industry works a 45-hour week, but the actual hours worked in Street are well short of that.’ Perhaps, but there was nothing slack about the figures. Turnover in 1947 reached £1,681,270, compared with £1,288,468 the previous year.

Time-keeping was not the chairman’s only gripe. Shortly after New Year 1948, he told the Factory Council that shops were still returning too many faulty shoes and that output had to increase still further. The Americans, he said, were producing ‘about half as much again per head per week as you do here. Our machines are the same, the conditions are the same; the only difference is the tempo of the work.’

Production did increase following the purchase of the manor house next to the Shepton Mallet factory, which came with twelve additional acres of land earmarked as the site of a new factory expressly for children’s shoes. And extra units were built in Bridgwater, which meant that by 1948 nearly a quarter of all Clarks shoes were made outside Street.

Bancroft developed the concept at Clarks that each manager had to draw up his own budget annually. These were added together to form the main budget, which the board reviewed and modified as appropriate. The revised figures were then handed back to the managers. Monthly accounts had to be produced with all items matched against their respective budgets. These accounts were published internally for the benefit of senior managers and directors in a ‘blue’ book, a process which still continues today.

A greater emphasis was put on time and motion studies, developing new manufacturing techniques and generally monitoring efficiency in minute detail, all of which had the unanimous support of Peter Clothier and Tony Clark, who were Bancroft’s right-hand men during the years of factory expansion. One member of the Clark family has described these three as ‘the Holy Trinity’. They were certainly close. Bancroft was the oldest – by six years from Tony and eight from Peter. Tony and Peter had spent a lot of time together as small children because Tony’s mother, Caroline Pease, died from an embolism twelve days after giving birth to her only child. Esther Clothier became something of a surrogate mother to Tony and it was through the Clothiers that Tony developed a great love for Bantham in South Devon. After the war, Peter Clothier and Tony Clark both bought houses there and in later years other members of the Clark family did likewise. There is still a strong family tradition of going to Bantham for short breaks and holidays.

Peter had been made managing director of the Avalon Leather Board Company in 1936 and became a director of C. & J. Clark three years later. His great expertise was machinery, whereas Tony Clark had a reputation for being, in the modern parlance, a ‘people person’. Tony was a liberal Quaker. He drank alcohol and hunted to hounds (as did his father, John Bright Clark). Bancroft was seen as the intellect, Peter as the technocrat and Tony as the life-enhancer.

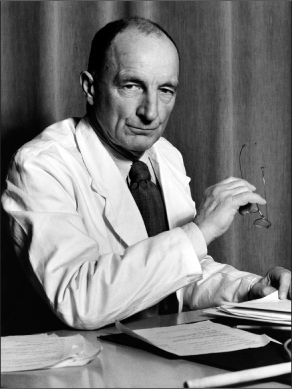

Tony Clark, described as one of the ‘Holy Trinity’; the other two were Bancroft Clark and Peter Clothier.

All three were adamant that establishing new centres of production under the control of competing managers was the way forward, and so rapid was this expansion that by 1960 there were, in addition to Bridgwater, Shepton Mallet and Street (which in itself had been greatly enlarged, especially with the opening of The Grove in 1950), eleven factories in the southwest – in Midsomer Norton (1952), Radstock (1953), Glastonbury (1954), Minehead (1954), Warminster (1956), Plymouth (1957), Weston-super-Mare (1958), Ilminster (1959), Yeovil (1960), Castle Cary (1960) and Bath (1961). Yet more would be opened during the 1960s in Exmouth, Barnstaple, Rothwell and New Tredegar (in south Wales). The Rothwell factory near Kettering in Northamptonshire, was bought in 1966 expressly to make men’s shoes.

The first truly devolved factory was Mayflower in Plymouth, which opened in October 1957. It was financed with help from Plymouth Corporation, which then rented it back to the company on a long lease. The Lord Mayor of Plymouth, Alderman Leslie F. Paul, cut the ceremonial ribbon, watched by Peter Clothier, who had ultimate responsibility for the factory. Plymouth concentrated on fashionable women’s shoes in the Wessex range. It was instructed to implement tight fiscal control over every aspect of its business, but had its own accounts department and work study team, which answered to local management rather than to Street. It also developed its own system of training unskilled labour and was seen as a pioneer of new technology. Every new employee received individual training and he or she was encouraged to suggest ways to speed up or simplify the work. If any of their ideas were adapted, they were rewarded. This scheme was another means of increasing production speeds, encouraging workers to resolve any issues around them and work together as one unit.

The imperative for efficiency was greater than ever as shoe imports from Western Europe surged: some 3.3 million pairs were imported in 1956, three times as many as in 1953, with Italy posing the greatest threat at the higher end of the market. Furthermore, the price of sole leather had continued to rise and this had to be passed on to retailers, who were beginning to baulk at what they were being asked to pay for stock.

Clarks, like other UK shoe manufacturers, was keen to use alternative resin-rubber soling material, but the government was allowing only small quantities of the ingredients needed to produce this to be imported from America and Canada. Factories such as the one in Plymouth had to find other ways not just to compete but to outperform their continental rivals. Speed of production was crucial. Peter Clothier determined that the conveyors in Plymouth were only to carry shoes being worked on at the time and not those awaiting attention. Maintenance of machinery was given a high priority on the principle that money spent on preventing breakdown was a saving on acquiring new equipment. There was also a radical rethink on the use of lasts. When the Mayflower factory opened, each last was used on average twice a week, in keeping with conventional shoemaking practice, but within months, individual lasts were being used on average 23 times a day – and a pair of shoes passed through the Mayflower factory in a mere three days.

Plymouth also developed a method whereby shoes were softened to make them easier to shape and work with in the final stages of assembly. This was called ‘rapid-mulling’ and involved the use of steam, as prescribed by scientists working at the Clarks laboratory in Street. According to Clarks of Street, 1825–1950:

They were exciting times for all concerned. Managers had to create, in their area, all aspects of factory activity, from the production of finished shoes to the organisation of workers councils. On their efficiency would depend the success of the firm in beating its rivals. In the early days, on the sturdy principle that they had to pay their own way, there had to be a good deal of improving, and anyone at any level who saw a real way to saving money or time was rewarded according to the amount saved.

Before the war, Clarks had developed the process of making what was called ‘Pussyfoot’ sheets from scrap crepe that proved suitable – and hardwearing – for shoe soling, but this was suspended except for certain government requirements. Then, immediately after the war, Clarks pioneered a new soling material called Solite, which wore significantly longer than leather and was regarded as more comfortable than Pussyfoot. Showcards for Clarks shoes made with Solite claimed they provided three times the wear and mothers were reminded that ‘active feet can run through a mint of shoe leather’.

Solite was developed out of a material initially discovered in the United States under the trade name Meolite. Its formulation was a closely guarded secret and was not easy to obtain in the UK. However, Clarks acquired samples and an in-house chemist, James Hill, analysed the material and found it was a styrene/butadiene co-polymer. By adding more styrene the end product was hardened whereas more butadiene softened the material. It could therefore be adapted to suit different types of footwear.

Clarks developed its own formula, and production began in the Rubber Department in Street in 1949. It was then manufactured in bulk at the Larkhill Rubber Company in Yeovil from around 1966 and sold to the external trade in addition to its own domestic use. The Plymouth factory used Solite extensively well into the 1970s, producing some 50,000 pairs of Women’s Court shoes a week.

The actress Moira Lister being fitted with Clarks Skyborne bootees at the Quality Footwear Exhibition, Seymour Hall, London, in November 1947. Hugh Clark is at her left.

One of the other major technological breakthroughs during this period was the introduction of the Construction Electric Mediano Automatico (CEMA) machine, which resulted from C. & J. Clark collaborating with the Grimoldi company in Spain, whose founder, Gonzalo Mediano de Capdevilla, was a circus performer and trick cyclist from Barcelona. CEMA allowed for the moulding of rubber soles directly on to the lasted leather upper, a revolutionary breakthrough because it did away entirely with labour-intensive methods of both machine-sewing and welting. It greatly improved the bond of sole to upper and was particularly suitable for children’s shoes and heavyweight men’s footwear, especially boots. CEMA produced shoes with far greater traction and soles that were waterproof. They also retained their shape and were regarded as supremely comfortable.

Mediano de Capdevilla’s first contact with C. & J. Clark had been in 1949 when Nathan Clark, one of Roger Clark’s sons and the inventor of the Desert Boot – who was then working with Arthur Halliday in Ireland – asked Bancroft permission to send Jack Clarke, the company engineer, to Barcelona to investigate this new discovery. Clarke was accompanied by Bob Cottier, Nathan’s assistant, who spoke good Spanish. Within weeks, an agreement was reached and by Christmas a CEMA machine was set up in Street, and Mediano de Capdevilla sent over two men, one a rubber technician, the other a mould maker, to demonstrate its powers. The two Spaniards stayed three months, during which time various modifications were made to their machine. If C. & J. Clark was to benefit fully from CEMA, it needed to be used on lines with long production runs (to keep mould costs low) and the curing time of the rubber needed to be as short as possible. The original Spanish machines had cure times of fifteen minutes, but the company’s own engineers managed to reduce this to as little as 3.5 minutes, depending on the style of shoe. In July 1950, C. & J. Clark placed an order for seven such machines from a firm of engineers in Chard and the company gave an undertaking to Mediano de Capdevilla that it would produce 2,500 pairs per week of children’s shoes in the Shepton Mallet factory – and that he would receive a royalty of one per cent on every CEMA-moulded shoe sold.

CEMA-moulded footwear was popular with the public and by December 1957 the two millionth pair of shoes made using this method had rolled off the assembly line. CEMA was a bright light in shoe production, and was only eclipsed in 1962 when Clarks began experimenting with injection moulded polyvinyl-chloride or PVC that required no curing time at all – although CEMA was still used on boots. Later, polyurethane (PU) proved even lighter and more hard-wearing than PVC.

Bancroft was jubilant about CEMA:

We believe we are the first in this country to make shoes this way and we think we are the only people making them with the precision necessary for our type and grade of product. We have faith that the project will be successful and hope that time will prove us right.

![]()

Bancroft recognised that the post-war ‘baby boom’ was good for business, possibly very good indeed. But winning the trust of the next generation of mothers was imperative if that business was to come Clarks’ way. Housewives needed to be convinced that their children would be wearing not just properly fitting shoes but shoes that would care for their feet. In the 1930s, many shops deployed the Pedescope to measure a child’s foot. This bulky contraption required the customer to stand on a step and look down at his or her feet through a pane of glass. It would remain a common feature in shoe shops until the early 1960s – but it came with a health warning: ‘Repeated exposure to X-rays may be harmful. It is unwise for customers to have more than twelve shoe-fitting exposures a year.’ On the other hand, you could have as many shoe-fitting exposures as was humanly possible if it involved the Clarks Footgauge.

This simple method of measuring feet accurately and quickly had been developed principally by John Walter Bostock during the late 1930s and early 1940s. American shoe manufacturers were well practised in offering their customers a variety of shoe sizes, though Clarks was not far behind them, especially with its anatomical range of Hygienic shoes that came in three separate widths and the women’s Wessex lines, which were offered in five width fittings and twelve sizes. After the Second World War, soldiers complained that their feet had suffered as a result of poorly fitting boots, prompting calls from the Boot and Shoe Industry Working Party Report for multi-fitting footwear in a variety of widths at affordable prices. It wanted ‘some enterprising medium price manufacturer (and/or distributor) to extend the multiple fitting trade downwards to the mass volume middle ranges of trade’.

Clarks and Somervell were at the forefront of this particular revolution, joined by the likes of Abbotts, Church’s, Feature Shoes, Lilley & Skinner, Lotus, Novic, Sexton and Timpson. In a 1947 document laboriously entitled ‘Retail Margins on Multiple Fitting Shoes’, a representative from Somervell told the board of the Trade and Federated Associations of Boot and Shoe Manufacturers that:

… there is no difficulty about measuring a foot with reasonable accuracy, and there is no difficulty in carrying a stock that will fit the bulk of feet, but measuring feet takes time and fitting feet slows down stock turn … You are only likely to get a reasonable standard of shoe fitting where people are prepared to pay for that standard of shoe-fitting and where the retailer finds it profitable to provide it.

Clarks begged to differ – and had done its homework. During the war, Bostock had arranged for every child in Street and every woman in the factory to have their feet properly measured. Then, in 1946, special fitting courses were held at the factory for Peter Lord salespeople and for those who worked in independent shoe shops that sold Clarks. These courses, which were normally held in rooms at The Bear Hotel opposite the factory, were expensive and time-consuming, but made sure Clarks was known as the company that looked after children’s feet (although the ‘Finder Board’ used by K Shoes and Howlett & White’s plastic gauge were widely available and would have claimed to do the job just as well).

Those who came to Street for one of these courses went away with a full set of instructions on a flyer entitled How To Use Clarks Footgauge, although something of a technical mind-set was required to decipher the full capabilities of this device. The manual started off simply enough: ‘Use on sloping table of fitting stool.’ But after that the going got heavier:

The gauge is marked with a scored line exactly nine inches from the inside of [the] heel pillar. Now place the size-scale plate so that when the toe-gauge slide is on this nine-inch line the pointer is exactly level with the 60 size mark. Having done this all other sizes will be accurately measured. See that the foot to be measured is at right angles to the leg … keep the toes flat with your thumb while adjusting the toe-gauge slide.

Measuring the customer’s foot accurately and quickly is crucial. This Clarks fitting stool with integrated footgauge of May 1957 did the job perfectly.

And on it went:

To measure the girth (or joint measure) move the tape carrier so that the tape comes immediately central with the great toe joint. The tape carrier should be pushed back at the outer side of the foot to the full extent of its swivel movement. This will cause the tape to run diagonally across the foot and will give a correct average position for measuring.

Eventually, the big moment arrives:

Take the reading on the tape and find the corresponding number from the printed scale in line with the size pointer. The column in which this number (or the number nearest to it) is found shows the correct fitting.

‘In between’ measures were a different matter and needed their own paragraphs of instructions.

Clarks took shoe-fitting so seriously that it continued to conduct its own research on the subject throughout the 1950s. At one point, the company embarked on a survey – an early exercise in market research – of 1,250 schoolchildren in Somerset and managed to persuade the county council and two prominent orthopaedic surgeons to back it. The survey revealed that in some towns, such as Taunton and Yeovil, as many as 44 per cent of children weren’t present when having shoes bought for them. This was horrifying. To Clarks, the very idea of buying a pair of children’s shoes that did not fit properly was deplorable. And the younger the customer the better. Children would be parents one day.

In-shop advertisements for Clarks ‘First Shoes’ spoke directly to responsible mothers:

Isn’t it exciting that your child is, at last, walking? And isn’t it so important that his or her First Shoe allows the soft, delicate bones to grow in a strong, healthy way? Clarks share your concern. That’s why all Clarks First Shoes come in a range of styles, in up to four width fittings and in whole and half sizes. Why we build at least three months growing room into all our shoes. And why the trained fitter in this shop will measure both tiny feet for width and length using a Clarks footgauge for guidance; you really can’t put your child’s feet in more caring, capable hands.

Where Clarks gained an advantage over its competitors was insisting that retailers carried shoes in all width fittings, and backing this up with a warehouse system that would speedily replenish stock rather than burdening retailers with an excessive number of unsold shoes that they had to store for several weeks.

Then, in the early 1960s, Clarks rolled out its successful ‘no fit, no sale’ campaign, which cemented the notion that the company prized comfort before profit. Bancroft would say many years later that the footgauge was the idea on which ‘the vast expansion in our children’s business was founded’.

Shop interior in Cheltenham in the mid-1950s, showing the children’s fitting area.

The teenage market had not been forgotten either. Indeed, in 1950, Clarks was the first British shoe manufacturer to produce a special range for young people, after Bill Graves made several investigative trips to America, where the idea of teenagers seeking greater independence from their parents was far more developed than in Britain. This forward thinking sat comfortably beside Clarks’ so-called ‘Style Centre’ in Street, where all kinds of fashion items from America and continental Europe were studied in detail – buckles, belts, fabrics, pullovers – to see how they might influence the design of shoes.

There was forward thinking, too, in promoting the Clarks brand. Advertising and celebrity endorsements had continued apace at C. & J. Clark as soon as wartime hostilities were over. Advertisements were placed on trains on the London Underground and in daily and Sunday newspapers, and famous names were invited to tour the factory – with their visits publicised far and wide. One such exercise in ‘under the line advertising’ took place in 1946 when Margaret Lockwood, probably the country’s most popular actress at the time, came to Street with her daughter – and the Bristol Evening World was invited along. It was, according to the gushing copy, ‘one of those happy occasions when the spirit of good humour is abroad and everything proceeds with cheerful spontaneity’. Lockwood – who had starred in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes in 1938 and more recently in the splendidly racy and controversial Gainsborough Studios melodrama The Wicked Lady in 1945 – was photographed arriving to a gathering throng, signing the visitors’ book, chatting to women in the Closing Room, watching as her daughter’s feet were measured and generally looking suitably impressed. ‘Miss Lockwood enjoys wearing Clarks shoes in private life and says that she frequently receives complimentary comments on her footwear’, the article concluded.

The British film star Margaret Lockwood and her daughter Toots arriving at Clarks in Street on 23 August 1946.

Royal connections were fostered. The then Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret were seen to be wearing Clarks shoes on their South African tour of 1947 and, by chance, the Queen, accompanied by Princess Elizabeth, Princess Margaret and the Duke of Edinburgh, visited the Clarks stand at the 1949 British Industries Fair at Olympia. A year earlier, Clarks had staged the first invitation-only private mannequin show ever to be held in Denmark, displaying 30 models of shoe. It took place at the Hotel Angleterre and was attended by some 130 buyers from Scandinavia and Holland.

Hugh Clark – in charge of home sales from the late 1920s until 1952 – took a keen interest in advertising and publicity. In April 1946, he explained:

Princess Margaret (at left) and Princess Elizabeth both wearing Clarks shoes during an official tour of South Africa in March 1947. Princess Elizabeth is wearing Montana sandals.

We have, as manufacturers, to educate the public on such things as the fitting of children’s shoes, we have to give information about trends in fashion, we have to present a case to the public and try to make people understand what kind of a firm is making their shoes. All these things, and many more, are part of the useful job that advertising must do.

Soliciting feedback from the public was encouraged, if only to pass on any favourable comments to the workforce as morale boosters. On one occasion, in response to the platform-soled, open-backed Roxanne shoe, a former Wren from Maidstone was moved to write a poem and send it to Street. It began:

I was reading the paper, and saw Roxanne.

And straight away out in the street, I ran

Thinking how lovely, how grand, how divine,

If I am lucky a pair will be mine.

![]()

Wilfrid Hinde’s role as export director had been taken over in 1946 by Nathan Clark, son of Roger Clark, and his department became known as the Overseas Division. Nathan, who had spent six years in Burma and India, appointed a fellow Royal Army Service Corps officer, Jack Rose-Smith, as sales manager, based in Street. Known as something of a free spirit within the Clark clan, Nathan occupied himself mainly with foreign licensing agreements to make shoes, while Rose-Smith took responsibility for direct export sales.

It was while Nathan was an officer in the Royal Army Service Corps in 1941 that he first chanced upon the idea of the Desert Boot. He had been posted to Burma and ordered to help establish a supply route from Rangoon to the Chinese forces at Chongqing. The road was never built after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, triggering a new phase in the Second World War, but Nathan had made a note of what soldiers were wearing on their feet and, minded that Bancroft had asked him to be on the lookout for new designs originating from that part of the world, he duly reported back. As it happened, he had not one but two novel ideas: the Desert Boot and the Chupplee. The latter – which was withdrawn from sale in the 1970s – was an open-toe sandal based on what men wore in Northwest India, with plenty of soft leather covering the contours of the foot. It was certainly not a flip-flop.

Nathan never drew a salary from Clarks and he left the company in 1951 to pursue his own interests. But in 1979 he explained that his inspiration for the Desert Boot came from

… crepe-soled rough suede boots which officers in the Eighth Army were in the habit of getting made in the Bazaar in Cairo. Some of these officers came to Burma, and this is where I saw them. It is said that the original idea was from officers of the South African Division in the desert and that the origin of theirs goes back to the Dutch Voertrekkers footwear made of rough, tanned leather called Veldt Schoen. This name is familiar to us in shoe manufacturing as the old name for the sandal veldt, or stitch-down process.

A Christmas card with a photograph of himself sent home by Nathan Clark while based in India during the Second World War.

Nathan sent sketches and rough patterns to Bancroft, but nothing happened until he returned to Street. Once back, he approached an experienced pattern cutter called Bill Tuxill, but, as Nathan put it:

… every time I went to see how my two shoes were getting on, I would see the sketches on his back shelf, and he would say with some embarrassment: ‘Yes, Mr Nathan, I will get on with them next thing.’

Eventually Nathan began cutting them himself, but when he produced trial samples they were not greeted with much enthusiasm.

A Londoner, Ken Crutchlow, gave the Desert Boot a spectacular publicity boost when he wore a pair to run across California’s Death Valley in 1970. Photographs accompanying the story were widely published.

Then, in 1949, while attending the Chicago Shoe Fair, he showed the samples to Oskar Schoefler, fashion editor of Esquire magazine, who was so impressed that he ran a whole feature on the shoe, complete with colour photographs. A star was born. It immediately sold well in America and Canada and became the first adult Clarks shoe to be made in Australia. In a 1957 advertisement, Clarks called Desert Boots the ‘world’s most travelled shoes’.

In Europe, Lancelot (Lance) Clark, son of Tony Clark, helped to popularise the Desert Boot and it reached record sales in 1971. A publicity coup had come a year earlier when Ken Crutchlow, an eccentric Englishman, ran 130 miles across Death Valley in California wearing a bowler hat on his head and Desert Boots on his feet. This was not a master stroke of product placement conjured up by Clarks executives, but the result of a $1,000 bet Crutchlow had with a friend. Pictures of Crutchlow in his Desert Boots appeared in more than 150 newspapers and magazines and were estimated to have been seen by 30 million people.

The Desert Boot has developed a momentum all of its own ever since – and led to some curious associations. Liam Gallagher, lead singer of the now disbanded rock band Oasis, and Clarks might not seem like a perfect fit, but the former rabble-rouser was so taken by the Desert Boot in the 1990s that he hardly wore anything else and then went one step further by collaborating with Clarks to design his own version of the boot as part of his Pretty Green clothing label. Not to be outdone, Bob Dylan and Robbie Williams were seen sporting Desert Boots around the same time and it wasn’t long before others jumped on the bandwagon. Sarah Jessica Parker was spotted in the David Z store in New York’s Soho buying two pairs, one brown, one black, because she couldn’t decide which colour she liked best. And the Jamaican rapper Vybz Kartel wove Desert Boots into one of his songs. Tony Blair, never one to miss a photo opportunity, opted two years into his premiership to wear a pair of Desert Boots in 1999 while promoting his Cool Britannia campaign.

The Desert Boot was nominated in 2009 by The Design Museum in London as one of the ’50 Shoes that Changed the World’ and by the beginning of 2012, more than 10 million pairs had been sold in over 100 countries. This is not a bad outcome for a shoe that its creator was told would never sell.

![]()

By 1945, exports had shrunk to virtually nothing, but two years later Clarks was doing business with Africa, Australasia, the Middle East, America, Canada, the West Indies, India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Scandinavia and Holland. In Holland, a Jewish refugee called Bob Arons proved sceptics wrong. Wilfrid Hinde had written to Arons telling him that ‘owing to a number of changed circumstances we are doubtful … our footwear can be sold again in Holland in worthwhile quantities’. A year on, in 1946, and Arons had sold 10,000 pairs in the Netherlands, turning over £43,500.

Nathan, in charge of the Overseas Division, was keen to find production partners abroad, but Bancroft was more cautious. Deals, however, were signed with two firms in Australia, Alma Shoes Ltd and Enterprise Shoe Company. Alma was founded in 1925 by Thomas Harrison, who had emigrated from Stockton-on-Tees in 1910. He died in 1936 and, although his son took over, the company was in trouble. Clarks agreed to take 51 per cent of Alma’s equity as part of what Nathan described to Bancroft as a ‘manufacturing service agreement’. Enterprise was a neighbouring shoe factory which was also in dire straits. It specialised in men’s boots and shoes. These two acquisitions led to the formation of Clarks Australia Ltd in the summer of 1948, structured in a similar way to Clarks Ireland Ltd.

In a minuted conversation, Nathan told Bancroft that ‘the time for development in overseas is now, and … the opportunity which exists for such development allows for no delay’. He wanted to push on in India, where he believed that independence would lead to protective tariffs on imports. Nathan felt a trading door was about to close. In 1948, he persuaded Bancroft to head East and organised meetings with Cooper, Allen & Co. and with the British India Corporation, but such was the political uncertainty in India that no deal was struck. Leaving Nathan in India, Bancroft returned to the UK on board Pan Am’s Empress of the Skies from Calcutta. During the flight, Bancroft had watched a small child running up and down the aisle wearing a pair of Clarks shoes. After landing in London, the Lockheed Constellation aircraft took off again en route to Shannon, in Ireland, from where it was scheduled to continue its journey to America. But it crashed near Shannon airport, killing all but one passenger. The child wearing Clarks did not survive.

Bancroft’s reluctance to rush into overseas production was not a new issue for C. & J. Clark. John Angell Peck, who had been appointed Clarks representative in Australia and New Zealand back in 1899 and who died in 1941, had repeatedly urged the board to open a factory in that part of the world to avoid import tariffs. But it never happened during Peck’s lifetime.

Bancroft’s official notes on overseas policy show that the board was ‘only prepared to experiment with overseas development … provided it [does not] endanger our home prosperity’. But Nathan continued to press for it, arguing the case for ‘putting our eggs in several baskets all over the world’, to which Bancroft responded that such a strategy was ‘hard to carry out when you were short of eggs … it was little use finding the eggs if you could not find the hens to sit on them’.

At one point, a deal was in the offing with the Port Elizabeth Boot Company in South Africa, whereby it would make women’s and children’s shoes, but this collapsed, whereupon Nathan focused his attention on Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

Clarks Australia Ltd began making shoes in Adelaide in 1949, while in New Zealand, where there had been an embargo on shoe imports for twelve years – with the exception of infants’ footwear – plans were afoot to make and market shoes through Clarks New Zealand Ltd.

Bancroft was fourteen years older than his brother Nathan. Their relationship was strained. Towards the end of 1949 – by which time Nathan was working at Halliday’s in Ireland – Bancroft jotted down his thoughts about the future of the Overseas Division, but there is no evidence that he made them public. In fact, eighteen months later, on 22 July 1951, he scribbled at the top of the first page: ‘No one saw this’. Perhaps his musings were cathartic. Certainly they were unsparing in their criticism of his globe-trotting brother:

NMC’s [Nathan Middleton Clark] effort is discursive. He flirts with new ideas such as selling last-making machinery and selling his latest patent on a royalty basis. He does this without carrying with him his home base and in his last promotion in the US makes statements [that are] untrue. In fact which were not checked by the responsible people in Street.

Writing in his own hand, Bancroft continued:

NMC suffers from lack of sustained effort. In Australia there has been no progress because of difficulties which have accumulated that side. NMC blames CJC [C. & J. Clark] for not developing new styles which he said in summer ’48 were needed … [but] NMC is no judge of what is right for the home market. He has no knowledge of it – no experience of it – he has the right and duty to bring back information and suggestions which may help to strengthen CJC in the home market but has no standing or position or right to criticise CJC’s home market operations.

Bancroft felt Nathan had wasted twelve months in Australia ‘shilly shallying’ and believed there was no point pursuing overseas production without a planned sales policy to go with it:

Without it the best manufacturing will fail from vacillation. I have told NMC this many times and sent him to Ireland last summer to work it out but he runs away from the problem.

Such was Bancroft’s exasperation that he expressed a ‘wide doubt’ as to whether Nathan had been suitable to run the Overseas Division at all.

His abilities are very great. He is a tremendous salesman and fruitful in ideas. I think it might be possible to run the OD [Overseas Division] if NMC were accepted as salesman and had under him a permanent deputy head of the OD through which all directions would go and who would be answerable for all actions of the others in the division. NMC has refused this and is working away from it.

Bancroft reported to the board at the end of 1949 that, under Nathan, the exports market had ‘on balance lost money’ and he expected the situation would not change in 1950.

![]()

Working at Clarks meant security – in many cases, a job for life. Maurice Burt joined Clarks in 1948 at the age of nineteen. His father was a labourer and he was brought up with his two brothers in Long Sutton, Somerset. On leaving school at fourteen, he joined a local woodwork company and then spent two years in the Royal Navy. Speaking in the summer of 2011 at his house in Street within walking distance of the factory, he describes his situation:

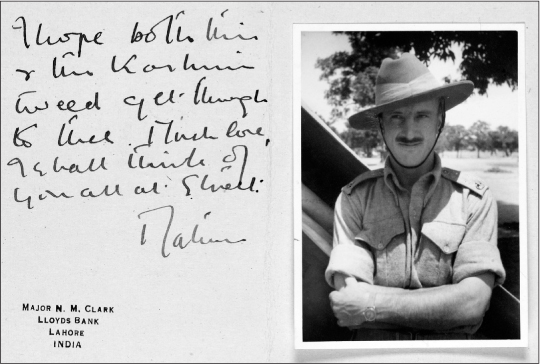

Press cutting at Street for the Skyline range in 1949.

When I came out of the Navy, Clarks was recruiting and really it was just a matter of turning up and filling out a form. They were looking for people and you had to be fairly backward not to be offered something. Because of the war and everything I didn’t have much of an education. I realised from an early age that I had to use my hands more than my brains if I was going to get on.

Maurice started in the finishing room doing odd jobs, which was something of a rite of passage for new recruits, a period of unofficial apprenticeship during which the supervisors – known as the ‘white coats’ – would assess work and attitude and place the men and women accordingly. In 1948, Maurice was on the equivalent of £2.50 a week. There were three grades of employee – weekly, fortnightly and monthly – but it took some considerable time to become a proper staff member if you joined straight from school. In Maurice’s case, his letter informing him that he was a fully signed-up member of staff was dated 12 January 1962, fourteen years after he first cycled over to Street for his interview.

Closing work, 1950.

It spelled out the terms and conditions of employment, making clear he would be joining the Staff Pension Scheme – an ‘expensive scheme that can only be maintained at its present level in times of good profit earnings’ stressed the letter. His pay rose to £15 a week in 1962 and his appointment was subject to one month’s notice on either side.

Patricia Andrews, who would become his wife, also worked in the factory, as did her father and as would Maurice’s and Patricia’s two daughters. In the November 1952 issue of the company’s News Sheet, there is a picture of Maurice and Patricia on their wedding day, standing outside the Street Methodist Church.

‘It was a sociable sort of place. My wife and I did most of our courting in the factory,’ says Maurice. He continues:

Our manager was Peter Clothier and there were a few times when he turned a blind eye to what we were up to. We all used to work 8am to 6pm and on Saturday mornings. But to tell the truth, we never really started working much before 8.30am because there was a lot of chat to sort out first. Once you went on staff you pretty much had a job for life and that was the important thing. The feeling on the factory floor was that everything was alright while the family was in charge but when the outsiders started coming in they were desperate to show how brilliant they were – and things changed.

The company’s 125th anniversary was celebrated in June 1950. Every member of staff was given a commemorative silver spoon in a little green box and a party was held in the newly opened Grove factory in Street, enlivened by the Sydney Lipton orchestra from London, which specialised in dance hall music. No alcohol was consumed – on the premises at least. Maurice Burt didn’t go because he was unattached at the time and felt awkward attending on his own.

![]()

Peter Lord Ltd opened its fortieth shop in December 1952 in Tunbridge Wells, and the actress Yvonne Marsh was invited to cut the ribbon. This outlet was seen as a template for modern retail design, with its large glass doors and glass-fronted displays at the entrance, showing off as many lines as possible. The ‘Women’s Fitting Room’, as it was called, was on the ground floor, children’s and men’s on the first floor. While having their feet measured, children were given a teddy to cuddle and sat on a chair that looked like a big drum. The message to shoppers was that Clarks represented affordable high fashion, and that Peter Lord sales staff were knowledgeable, trustworthy and always on the side of the consumer.

Bancroft described the Peter Lord shops as ‘testing consumer reaction to our merchandise and to our methods of sale and promotion’, but he also put out a statement to all sections of the trade in 1953, reiterating the company’s commitment to the independent retailer and stressing that Peter Lord – which three years later would open a shop in Regent Street, its first in the West End of London – accounted for only 10 per cent of Clarks sales. Maintaining a balance between building up its own Peter Lord retail chain, while not antagonising the independent stores that sold Clarks, was a delicate task. He wrote:

The showroom at Mitre House, the Clarks London office in Regent Street, in 1950.

We must always bear in mind the tremendous advantage the independent retailer has over the multiple retailing organisation … we also believe that as manufacturers we have shoes the public want, and we know that we have a knowledge of advertising and style to enable them to maintain their favour with the public. We … believe in the independent retailer, those shops which absorb the major part of our distribution; and we feel sure that our policy of relying upon the independent retailer and the departmental store as the main outlet for 90 per cent of our pairage is a good one because it compels us to continue the healthy fight of competition in matters of style, quality and value offered.

But the world of shoe retail was about to be shaken like never before. Bancroft was not the only one who thought that footwear in Britain was a potential honeypot. Charles Clore was on the prowl, his prey waiting quietly, invitingly, on every high street in every major town and city and in many smaller ones as well.

Clore was the son of Israel Claw, a Russian Jew born in Kovno, Lithuania, who brought his family to London in 1888. Israel’s first job was as a cobbler, but it wasn’t long before he had started a thriving rag trade business in the East End. His son was born on Boxing Day 1904 and would become one of the most controversial, feared and enthralling entrepreneurs of the twentieth century. Regarded by some people as the man who invented the take-over, his first purchase was the ailing Cricklewood Skating Rink in 1928, followed three years later by the loss-making Prince of Wales theatre on London’s Coventry Street.

By 1953, Clore had amassed a fortune. As a frequent visitor to the United States, he had looked carefully at shoe businesses, noting that American women bought on average twice as many pairs of shoes each year as British women. He reasoned that it was only a matter of time before the British would catch up.

On returning from one such visit, Clore’s friend Douglas Tovey, an ambitious and gregarious estate agent who worked for a firm called Healey & Baker, alerted him to Sears & Co (the True-Form Boot Company), which owned Freeman, Hardy & Willis and Trueform, comprising some 920 outlets across the country. Clore was interested in the shoes, but he was even more taken by the shops in which the shoes were sold. With Tovey’s help, he worked out that the value of the retail properties greatly exceeded the value of the shares in the company – and in February 1953 he pounced, sending his offer direct to shareholders. As David Clutterbuck and Marion Devine wrote in Clore: The Man and his Millions:

To the board of Sears, the sudden attack was devastating. Its response was confused and unconvincing. The idea that anyone would make such an approach direct to the shareholders was unbelievable. Worse, it was ungentlemanly.

Accusations of ungentlemanly behaviour had never stopped Clore in the past. He had studied the tactics of American companies when confronted with hostile bids and was fully prepared for the unfolding furore. According to Clutterbuck and Devine:

What offended so many people in the City was that Charles [Clore] had broken the convention that acquisitions should be by agreement. It was felt to be the equivalent of being asked to dinner and stealing the silverware. It was unthinkable, an outrage, yet it was legal and it was done.

Retail was in his blood from an early age, when he used to sell newspapers on street corners, and he had successfully built up Richard Shops, a retail chain that he bought low and sold high in 1949. Sears chairman Dudley Church was reported as saying: ‘We never thought anything like this would happen to us’, and the Sears family was incandescent with rage at the speed of events. But the deal was done and within twelve months, the sale and leaseback of properties to Legal & General raised £10 million, with Clore telling shareholders at the 1954 annual general meeting that the company still retained more than £3 million worth of freehold factories, warehouses and shops. Clore said:

The first call on this money will be the requirements of the footwear business to enable it to carry through the programme of improvements and expansion … it is not in the interests either of the shareholders or of the National Economy for a Company such as ours to retain vast sums locked up in freehold properties … our capital should be employed primarily in our own business of making and selling boots and shoes.

Buying up smaller shoe companies was another vital part of Clore’s strategy. In 1954, Freeman, Hardy & Willis acquired Harry Levison’s Fortress Shoe Company, which had 39 high street outlets, a deal that resulted in Levison, whom Clore admired as an arbiter of modern fashion, eventually taking over the entire management of Clore’s shoe empire. Fortress was renamed Curtess and then Freeman, Hardy & Willis bought Philips Brothers’ Character Shoes Ltd for £700,000.

Work in the sole room at Street, 1950.

J. Sears became Sears Holdings shortly before the Philips Brothers’ acquisition, after which Dolcis was acquired for £6 million, followed by Saxone, Lilley & Skinner and Manfield in 1956. The Dolcis deal alarmed Clarks. Prior to the September board meeting, Bancroft circulated his thoughts to other directors:

Clore’s group has total assets of approximately £20 million and is therefore about four times as large as we are … there is nobody in the USA now of similar dimensions.

Others shared his concern. Writing in the Sunday Express that same month, Edward Westropp, the paper’s City Editor, said it was ‘just another dreary financial deal, just another company changing hands. What interest could that possibly be to us – the shoppers of Britain?’ Then he went on to answer his own question, warning that Clore was robbing consumers of proper choice

Now is the time to let the shopper know who he is going to. Let it be obligatory to put the name of the real owner or parent company in big letters over the door.

On seeing Westropp’s piece, Cecil Notley, Clarks’ advertising man, wrote to Bancroft wondering if the chairman might have ‘inspired the article’, adding that ‘it seems to be just what the doctor ordered’.

Along the way, Clore formed the British Shoe Corporation as an umbrella organisation for his footwear operations, electing to establish the headquarters in Leicester rather than using Freeman, Hardy &Willis’s main offices in Northampton. By 1962, the British Shoe Corporation controlled 2,000 shops.

This dramatic concentration in shoe retailing was at odds with the ongoing diversity of shoe production. In 1956, there were still some 1,000 firms in the business of making footwear in Britain, of which more than 80 per cent employed fewer than 200 people. Only around 50 shoe manufacturers had a workforce in excess of more than 400. Clarks was the largest single manufacturer in the country.

![]()

Clarks was not only a recognised and respected name on the British high street but was close to becoming a pillar of the establishment. Shortly before Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953 (during which she wore shoes designed by Roger Vivier), the company felt compelled to put out its own statement to mark ‘an event so momentous that all ordinary happenings lose something of their importance’. Describing the crowning of a young Queen as a ‘symbol of hope, of endeavour, of re-dedication to our duty’, the statement went on to declare that

A mid-1950s window display card for Clarks Teenagers shoes. Clarks had targeted the teenage market from 1950 onwards.

… if in these crowded islands we no longer have the surpluses of national wealth our forefathers enjoyed, if we have to depend more and more on hard work and the application of unceasing commitment to industrial, commercial, agricultural and educational needs in order to win through, we feel that in our Queen, already proven in the ordeal of tireless public service, we have a shining example, spurring us on to our goal. Invigorated by the spirit of youth and freedom which she manifests we can, and will, achieve a new and happy way of life.