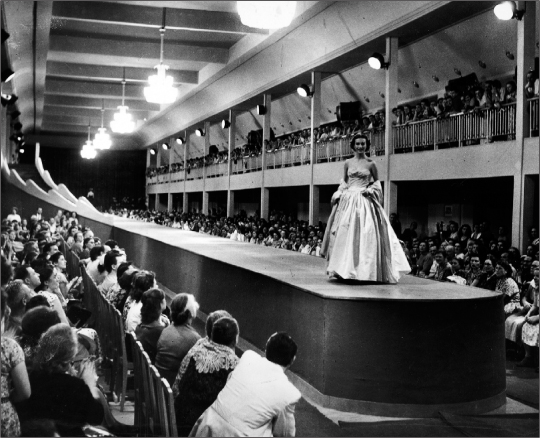

Clarks shoes on parade at a fashion show in Moscow in 1956.

THE 1960S BEGAN WITH A SWING. And in Street there were no signs that the music would stop, or the party end. In the first year of that decade, Clarks recorded sales of £18,482,000 and a pre-tax profit of £1,446,000, up 10 per cent on the previous year.

‘Our rate of expansion is rapid,’ wrote Bancroft Clark in the Annual Report and Accounts for the year ending 31 December 1960. He continued:

In the four years from 1956 to 1960, total assets have nearly doubled … such continuity of good trading is unusual. It may be that the public is turning away from consumer durables, the demand for which, I think, began to fall off before the latest credit squeeze. The public may be more interested in dress, including shoes, than it has been since the end of the War … we had not forecast such good demand.

This was the period when Clarks factories were at the fulcrum of its business and when the broader Clarks community flourished like never before. Demand was so strong that in the autumn of 1960 the factories were running at full capacity – and yet retailers were still complaining of a lack of stock. Clarks was not the only footwear company in celebratory mode. It had been a spectacular year for the whole of the trade in the UK. But it wasn’t just UK shoemakers who were doing well. At the same time, imports of cheaper shoes from abroad also reached a post-war record.

Demand for shoes may have been on the increase, but so too were manufacturing costs. In 1960, wages in Clarks factories increased by 3 per cent – with a further 3 per cent rise scheduled for February 1961. At the same time, in 1960, the working week was reduced from 45 to 43¾ hours. Later on, it was to be reduced yet further to 41½ hours. Rather than increase prices – except on some of Clarks’ more popular children’s lines – Bancroft’s answer to raised costs was to pursue new, more economical methods of production:

If these come off and if we can exploit them, they should enable us to offer better value, make more money and sell shoes at lower prices … These are techniques which are used by the vast mass production factories of Russia and Czechoslovakia and which have not, hitherto, generally speaking been applied to the smaller factories and shorter runs of the shoe trade in the western world.

As well as providing inspiration for economical production methods, with a huge order for women’s footwear, Russia also contributed to the boost in Clarks exports which, overall, exceeded £1 million for the first time. The interest from Russia would lead to Clarks periodically advertising on Soviet State television, particularly during extreme, cold winters when freezing Russians were reminded of the warmth and comfort of Clarks’ wool-lined range of ‘Igloo’ boots. In 1959, Bancroft and his eldest son, Daniel Clark, were among a group of shoe manufacturers from the UK who visited Moscow and Leningrad in the Soviet Union, and Kiev in the Ukraine. They were accompanied on this busy, eleven-day fact-finding mission by a member of the BBC’s Overseas Monitoring Service, who acted as interpreter. The consensus was that the Russians were ahead of the west when it came to the vulcanising of microcellular soling – or rubber soles – and other non-leather progressions in the trade, but were way behind in styling, particularly of women’s shoes, which, Bancroft noted, in the Soviet Union tended to have thick, rounded toes and chunky heels. The really good news, however, was learning that although the Soviet Union intended to increase its shoe production by 50 per cent over the next five years, it had no plans to build new factories to achieve this ambitious goal. Almost certainly, the Soviets would have to rely on imports.

Clarks shoes on parade at a fashion show in Moscow in 1956.

There had also been a development in Canada a few months before the Coronation, when Clarks bought the loss-making Blachford Shoe Manufacturing Company Ltd. Founded in 1914 by two brothers, Blachford specialised in high-grade welted women’s shoes, making 100,000 pairs a year, and the board was confident that it could be turned around. With the company came a coast-to-coast sales organisation, which Jack Rose-Smith, who had brokered the deal, hoped would double Blachford sales within two years. In fact, despite the efforts of several senior directors who made visits to Ontario – including Bancroft himself – the Canadian operation was a burden. A loss of £8,000 in its first year was understandable, but explaining further losses of £18,000 in 1954 was more difficult. By the end of 1956, Bancroft wasn’t bothering to give exact sales figures, bluntly reporting in the Annual Report and Accounts that ‘Canada again lost a large sum’. And in 1960, he simply wrote: ‘Canada business is bad’.

Meanwhile, sales in markets elsewhere in the world were mixed. Business in Africa was strong and accounted for nearly a quarter of Clarks exports, while the West Indies and to a lesser extent Europe were proving to be encouraging. Trade with America was tough, but it was better in Australia where, in 1959, the company had bought the majority of shares in G. T. Harrison Shoes Ltd, the firm which had begun manufacturing Clarks under licence almost a decade earlier. Then, in the spring of 1960, Clarks acquired Diamond Shoes Ltd, a Melbourne firm specialising in women’s shoes. There were now three factories in Australia, with a fourth soon to open in Adelaide.

Production of Clarks Torflex children’s shoes in New Zealand began in 1961, and closer to home a new factory was built on the Dundalk site in Ireland. Shortly afterwards, Clarks acquired the Irish manufacturer Padmore & Barnes Ltd, in Kilkenny, a move which meant that worldwide, Clarks now employed more than 10,000 people and made nearly 11 million pairs of shoes a year.

In an effort to bring together all overseas shoes interests, the board had decided, in 1959, to form a new division called Clarks Overseas Shoes Ltd, which was responsible for exports from the UK, manufacturing in Ireland, Australia and Canada; manufacturing under licence in New Zealand and South Africa; and wholesaling in the United States and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Arthur Halliday was made managing director and Jack Rose-Smith a director.

Meanwhile, at head office in Street, Bill Graves, who was not a family member, became a director. He had joined the company in 1933 at the age of fourteen and attended Strode School in Street. After rising swiftly through the ranks, he proved to be a big success as head of production of children’s footwear and was still only 41 when appointed to the ten-man board. In 1960, there were four other non-family directors: Arthur Halliday, Jack Davis, Leslie Graves (Bill’s older brother) and Reginald C. Hart.

The issue of what roles members of the family should play in the firm would test Clarks in the years to come. Bancroft found it a vexing and at times tiresome discussion, even though in 1960 he made a point of saying that ‘the key to a successful future lies with securing good professional management at all levels’. He went on to explain that by ‘professional’ he meant:

… those who have been trained for the execution of their management duties and who give full-time devotion to them … we seek to bring in outsiders, as well as able members of the shareholding families who are interested and will accept appointment on these conditions.

Bancroft made a special effort to check up on the fifth generation as they approached the start of their working lives. In the autumn of 1959, he went to see Tony Clark’s son, Lance, who was reading geography at Oxford university and considering a career in the colonial service. Lance was an exceptional rugby player, who went on to play for Bath.

‘Bancroft said I should try six weeks working in Street – and I’ve been there nearly 60 years,’ says Lance, who, when interviewed in 2011, was still working as a consultant at Clarks, reporting directly to the chief executive.

Lance developed a particular interest in how shoes were made. After building a relationship with Peter Sapper, a German with a small moccasin business called Sioux, Lance, while working at Padmore & Barnes in Ireland (part of Clarks Ireland Ltd), was responsible for ‘Project M’, which came to fruition in 1967 with the launch of the Wallabee. This iconic shoe – a lace-up with crêpe sole, inspired by classic men’s moccasins – was at first regarded as too radical for the British market but enjoyed almost immediate success in North America. To advertise the Wallabees, the largest billboard ever seen up to that time on the North American continent (it measured 185ft by 45ft) was erected in Toronto, Canada, next to a highway used by more than 250,000 motorists every day. By 1973, the two Padmore & Barnes factories – in Kilkenny and Clonwell – made little else other than Wallabees, producing some 18,000 pairs a week.

Other members of the fifth generation who played prominent roles during the 1960s and 1970s were Jan and Richard Clark, the second and third surviving sons of Bancroft and Cato Clark.

This billboard advertising Clarks Wallabees in Toronto in 1967 was at that time the largest ever seen in North America.

‘Most members of the family went down the same route on leaving university’ says Richard Clark, who graduated from Cambridge university in 1961. He continues:

We were a manufacturing company based in Street and our education in the business tended to follow similar lines. I spent about six weeks in various independent shoe retailers and then some time at Peter Lord. I also went to a tannery and a factory in France. Then Bill Graves gave me a job as a factory assistant and had me working on projects related to children’s shoes. Eventually, I went to Ireland and ran the New Forest factory at Dundalk, which was making women’s runabouts called Serenity.

Bancroft persistently worried about finding jobs for family members – or, at least, the right jobs. Shortly before his retirement in 1967, he wrote a document called ‘Management Changes’, in which he cited the example of Anthony Clothier, eldest son of Peter Clothier (grandson of William S. Clark), who had gained promotion to ‘something within Clarks Ltd, before he had mastered and made a success of his present job’. According to the minutes of a board meeting held in 1967, this was a view shared by Tony Clark, but Stephen Clark said in a note to Bancroft that:

… the apparent nepotism that you are feeling puritanical about is an advantage to the business. Without it we would not have had the guts to put people as young as Anthony [Clothier] and Jan [Clark] into their present job. We should have filled them by seniority, with someone of 40 and had we done that we should not have been acting in the best interests of the shareholders.

Anthony in fact rose within Clarks to become a main board director from 1977 until 1986. He was later president of the British Footwear Manufacturers Federation on two occasions, and president of the European Shoe Federation from 1979 to 1983.

![]()

The Clarks commitment to Street in the 1960s remained consistent with its Quaker heritage. In 1959, the Clark Foundation was set up to fund educational and recreational opportunities for all ages. In 1963, for example, the Strode Theatre opened, funded entirely by the foundation and drawing in audiences from around the West Country for plays, films, pantomimes and revues. One notable landmark was its staging of the premiere of William Douglas Home’s The Secretary Bird, which went on to enjoy stellar success in London’s West End.

Clarks spent £9,000 on an extension to the Street library, after which more than a third of the town signed up to become registered readers. The foundation also paid a contribution of £35,500 towards a sports hall for Strode College, formerly known as Strode Technical College, and £80,000 towards changing Strode School into a comprehensive, Crispin School. It also paid £47,000 for a new pavilion and to renovate the field of Victoria Athletic Field and Club for use by members of the public and not just Clarks employees. More controversially, Clarks helped facilitate the provision of a relief road around Street to encourage lorries and other heavy vehicles not to clog up the narrow town centre. Some shops and small businesses expressed their reservations, arguing that they would lose business from the by-pass, but the work went ahead anyway and the road remains in place today.

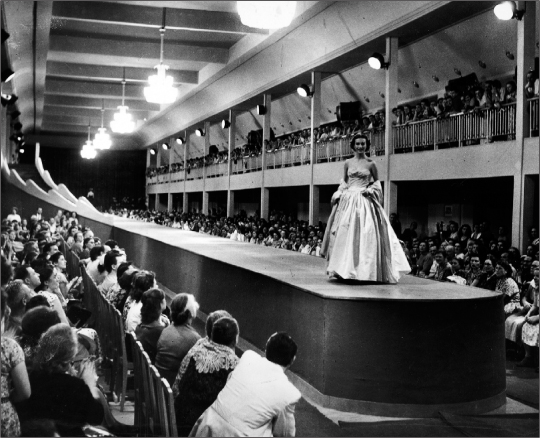

James Lidbetter, the Street librarian, stands in the new library extension built in 1959.

The sense of community, a world within a world, was reinforced in 1957 when the company launched Clarks Courier, a newspaper which for some years was published in addition to Clarks Comments. Although intended to fill a perceived need for better and more widespread communication, the Clarks Courier – which over the years became referred to simply as the Courier – was read not merely by Clarks employees. You could pick up a copy for 2d. on Street’s High Street. The paper was printed fortnightly on presses belonging to the Bristol Evening World, and its policy and editorial content were determined by the Clarks public relations department, which in turn liaised with Vernon Smart, the personnel director, particularly over sensitive matters of labour relations.

To dismiss the Courier as a management propaganda sheet would do a disservice to those who submitted copy from the far reaches of the Clarks empire, often with judicious wit and an enviable attention to detail. Correspondents were appointed in each factory and there were regular columns, such as the ‘Shepton Notebook’ and ‘Irish Diary’.

A full listing of cinema showings throughout the region was run in every issue, along with classified and display ads and an entertainment guide called ‘The Best in the West’. There was a regular full-page feature called ‘Taken for Granted – Courier looks at jobs that rarely make the limelight’, and the ‘Pet Portrait Competition’ was well-received by readers.

‘The editorial policy of Courier is one of neutrality,’ wrote David Boyce, one of the paper’s senior editors in 1960:

The paper is neither pro-management nor pro-employee. It sits on the fence and holds a purely watching brief. It is a mouthpiece for both management and employees alike; within its pages can appear advance news of developments within the industry, details of new techniques, department changes and personality profiles. All reported without fear or favour.

Certainly, at the start of the 1960s, there were plenty of changes to report on as Clarks embarked upon another structural reorganisation aimed at addressing the burgeoning and complex businesses both in Britain and abroad.

In 1960, C. & J. Clark became a holding company with four main subsidiaries, of which the biggest was the UK shoemaking and wholesaling operation, known as Clarks Ltd. Bancroft assumed the role of chairman of both C. & J. Clark and Clarks Ltd. The second subsidiary, Clarks Overseas Shoes Ltd, remained as it was, with Arthur Halliday as managing director and Jack Rose-Smith as his number two; C. & J. Clark Retailing Ltd, which at that stage consisted of the Peter Lord shops, was the domain of Reginald Hart, and Avalon Industries Ltd was a new holding company for various subsidiaries relating to Clarks shoe components and engineering interests. Avalon Industries was under the control of Stephen Clark.

Street Estates Ltd, a property and estates management company, was also part of Clarks, although it was not at this stage included in the annual accounts. It had been formed in 1930 to oversee the non-industrial properties in Street, which the company had either built or bought as housing for its workers. By the early 1940s, there were around 100 such Street Estates properties. In 1961, more than 60 per cent of its portfolio was made up of industrial buildings; 20 per cent residential and 20 per cent of unspecified land in and around the town.

The reorganisation at Avalon Industries meant there were related companies dotted about the West Country, trading variously in materials, chemicals, components and machinery used by shoe manufacturers. In 1961 Avalon Industries was made up of: The Avalon Leather Board Company, based in Street, which had been started by William S. Clark in 1877; C. I. C. Engineering Ltd, in Bath, which would merge with Ralphs Unified in 1966; Avalon Shoe Supplies Ltd, the sales company of the Avalon group; The Larkhill Rubber Company Ltd, which made all types of rubber and PVC soles; Strode Components Ltd, with three factories – in Street, Warminster and Castle Cary – making plastic heels, wedges, cut-crepe soles, insoles, lasts and steel shanks; and Avalon Chemicals, which produced adhesives, resins and polyurethane compounds (often known in the trade as PU) from a factory in Shepton Mallet regarded as the most advanced pre-polymer plant in the world.

Not all of these were run by members of the family, but in 1961 Bancroft’s son Daniel, aged 30, was put in charge of Strode Components and Ralph Clark, 35, was made manager of the Larkhill Rubber Company, which moved that year from its cramped premises in Street to a newly built £250,000 factory just outside Yeovil. The rubber factory was particularly important because, in addition to Clarks, it also supplied all three of the other big shoe manufacturers in the UK: K Shoes, Lotus and Norvic.

Ralph Clark was the son of Alfred Clark, a science academic and Fellow of the Royal Society who taught at Edinburgh University. On leaving school in Edinburgh, Ralph was offered a scholarship to King’s College, Cambridge, where he read history. On graduating from Cambridge university, Ralph had hoped to join the Royal Navy, but was prevented from doing so because he was colour blind. Instead, he was offered a job in personnel at the Colonial Development Corporation. In 1952, he attended a family wedding in Street and fell into conversation with his cousin, Bancroft, who asked him to join the firm.

I had never thought of going into the business, and to begin with I wasn’t sure what my job was. I had more or less a free hand and was expected to attach myself to something or other, generally make myself useful. I hung around the rubber factory and saw that it was grossly mismanaged. Eventually, Bancroft asked me if I would take it over and I had to build up the new factory from scratch. I was a complete amateur and I’m not sure I covered myself in glory.

After a disagreement on sales strategy with Stephen Clark, chairman of Avalon Industries, in which Bancroft took Stephen’s side, there were, according to Ralph, ‘two years of guerrilla warfare’ during which:

… Stephen got a bee in his bonnet about setting up a sales company to handle all Avalon’s products. I objected strongly to this because it wasn’t as if we were selling a finished project. Clearly, Stephen thought my view was useless and then I found myself in an embarrassing corner when Bancroft sided with Stephen and said I had to go along with what was proposed. I said I would, but not willingly, and that made me even more unpopular. Then we started making serious money and I stayed 20 years at the rubber factory.

Not long after, in 1965, Ralph took over as chairman of Avalon Industries when Stephen became Company Secretary of C. & J. Clark, a post he held until his retirement in 1975.

The Larkhill Rubber Company Ltd, like other parts of the business, benefited from Clarks moving into the computer age. The company had acquired two rented IBM 305s early in 1960, which became a source of much interest among other companies. But it had taken Clarks’ computer specialist, Roy Wilmot, more than 24 months to persuade the board of the data-processing merits of computers. This was one innovation that Clarks was slow to embrace. In Towards Precision Shoemaking, Kenneth Hudson wrote:

The use of all this data had not always been immediately apparent to the senior members of the management staff for whom it was intended and, in a wise and successful attempt to improve understanding, a Trojan-horse approach was adopted, whereby a young man who loved and respected computers was somehow attached to each relevant and influential department head, to act as a combination of interpreter and computer’s friend. Less reverent observers have described these indispensable aides as plumbers’ mates.

Meanwhile, on the high streets of Britain, the growing power and influence of Charles Clore’s British Shoe Corporation continued to pose a threat to Clarks, but it also presented the company with an opportunity. The threat was evident enough. Clore’s shops could opt to stop selling Clarks altogether as the British Shoe Corporation looked to source cheaper shoes from overseas. And although Clarks had its own Peter Lord outlets, these were under no obligation to buy from Clarks for fear of antagonising the independents specialising in or selling Clarks shoes in high numbers. It was a state of affairs that gave rise to tension between the production and retailing arms of the company, a rift that continued for several decades. It was, in fact, a growing sore that only went away many years later, once Clarks finally stopped making shoes altogether.

The opportunity presented by the British Shoe Corporation was for Clarks to strengthen its position in the unbranded shoe market. Freeman, Hardy & Willis, Saxone, Manfield and many of the other shoe companies that made up the British Shoe Corporation were not manufacturers. They were strictly in the retail and marketing business, buying in unbranded shoes and selling them under their own name direct to consumers. Clarks already had some experience as manufacturers of unbranded shoes, having created a subsidiary expressly for this purpose in 1957 called Wansdyke Shoes Ltd, which operated from a factory in Bath. In the 1960 Annual General Report, Bancroft said:

A shopfront in Ellesmere Port, Cheshire, in 1963, prominently promoting Clarks shoes.

Our plans are to extend this company [Wansdyke] so as to be able to exploit the Clarks shoe-making techniques in markets where we are unable to do so on a Clarks branded basis.

Wansdyke had been making shoes for high-end customers such as Harrods and low-end ones such as Barratts (‘Walk the Barratt Way’), a company that Clore, much to his annoyance, failed to buy in 1964, despite offering in excess of £5 million for a majority shareholding. In the 1960s, the plan was for Wansdyke to concentrate on making cheaper shoes – mainly sandals – supplying principally the British Shoe Corporation and Marks & Spencer. It was hoped that Wansdyke would make 10,000 pairs a week, but in reality it seldom produced more than 3,000. The contract with Marks & Spencer stuttered and stalled for a few months before it petered out altogether in May 1962 following rows about price increases and the speed of production. At one point, Marks & Spencer complained that:

… when we started with Wansdyke we were given to understand that this venture would receive the fullest support and cooperation of Clarke’s [sic] organisation, and that the great fund of knowledge available at Clarke’s [sic] would be at the disposal of the new company.

The following year, in 1963, Wansdyke temporarily stopped supplying the British Shoe Corporation, but resumed making shoes for Marks & Spencer. It was also continuing to do business with, among others, Barratts, Debenhams, Lennards, Mothercare and Stead and Simpson. The on-off relationship with Clore’s British Shoe Corporation intensified when Clarks bought A. & F. Shoes Ltd in 1962 and London Lane Ltd in 1965, both small, London-based firms producing mainly high-fashion footwear. This was part of a drive to attract younger consumers – the so-called ‘with it’ crowd. Peter Clothier, who was in charge of women’s shoe production in the UK, felt strongly about this market. Speaking at the 1960 annual Dinner of the London and Southern Counties Shoe Retailers’ Association, Clothier said:

To sell more shoes, we must turn to the younger generation who are now so often the initiators and first acceptors of fashion trends. It is no use manufacturers and retailers setting themselves up as a committee of vigilantes to decide what young people will buy … young people today have minds of their own and only when they see irresistible shoes irresistibly displayed in every shoe shop will the impact be irresistible.

But Clothier appeared less sure of himself when it came to dealing with the British Shoe Corporation. In a confidential note to Bancroft, he outlined eight options facing Clarks. Option three was:

If C.J.C.’s [Clarks] intention is not substantially to expand in retailing there would be clear advantage and not too much danger in developing business with BSC [the British Shoe Corporation].

Option four presented an entirely different scenario:

If C.J.C.’s intention is to expand in retailing, there would sooner or later be a clash with BSC, where they say in effect ‘if you go ahead in retailing we throw you out’.

Clothier went on to conclude that:

… in this uncertain position, I would doubt if it is worth going far out of our way or risking serious loss of business from existing accounts to build up even a substantial trade with BSC … may it not be wiser policy in the long run to build business with, and strengthen our links in every way we can with those multiples who are independent of BSC, both because that business is likely to be on a surer footing and because they are easier prospects for us to absorb as time goes on if we so wish.

Acknowledging that the British Shoe Corporation had ‘wonderful sites’ and plenty of them, Clothier said Clarks needed to find ‘more efficient retailers than BSC’ who would offer better terms of business. But, in what could be regarded as an anachronism, the terms of business were not always favourable in relation to the Clarks-owned Peter Lord shops, never mind the British Shoe Corporation or the remaining independents. In fact, Peter Lord was at times more independent than the independents.

Bancroft became sufficiently rattled by Clore that on 30 March 1962 he fired off a letter to Keith Joseph, the Minister of State at the Board of Trade, complaining of what he saw as the British Shoe Corporation’s ‘monopoly’. Joseph replied by agreeing that Bancroft should meet his parliamentary secretary, Niall Macpherson. A meeting took place on 10 April 1962, attended by Bancroft, Macpherson and three civil servants. The outcome was disappointing. In a note written the day after the meeting, Bancroft recorded:

I described the present situation where the Clore group controls 50 per cent of the multiple business, 33 per cent of the specialist shoe shop business, and 22 per cent of shoes sold in the UK … that the effect of their controlling 50 per cent of the multiple business made them dominant in the city centre selling of shoes, and this was a difficult position … I asked whether the government’s view and policy on monopoly had changed and whether it ought to change. The answer was no, that they are not contemplating any change.

A year later, Sears Holdings – the British Shoe Corporation’s parent company – announced record profits that were 22 per cent up on the previous year. Clore was typically punchy, telling shareholders that the directors of Sears and of the British Shoe Corporation ‘are constantly examining suitable ways of expanding the activities of the group, whether by acquisition or development of existing businesses’. Sears was already a huge and diverse group, embracing everything from shipbuilding (Furness Shipbuilding Company Ltd) and mining (Parmeko Ltd) to laundry and dry cleaning equipment (Brown & Green Ltd) and air conditioning (Mellor Bromley Ltd). It had also bought two prestigious West End jewellers, Mappin & Webb and Garrard & Co. Ltd.

Over the next few years, Clarks and the British Shoe Corporation played a cat-and-mouse game. In March 1966, Tony Clark, managing director of C. & J. Clark, met his British Shoe Corporation counterpart, Harry Levison, at a ‘private, social occasion’, during which Levison claimed that Clore left him alone to run the business as he saw fit. The two men discussed the small matter of large mark-ups, with Levison insisting that 45 per cent was his ‘minimum standard’. Tony later wrote:

He [Levison] says branded manufacturers, including Clarks, are always welcome and should keep in touch with his various buyers, although they will be wasting everyone’s time unless they get the 45 per cent mark-up firmly into their heads!

![]()

Clarks’ enthusiasm for the youth market led to the national release of two cinema commercials for the Wessex line (Clarks’ umbrella brand for mass-produced lines), filmed in colour and shown in more than 1,000 cinemas. In the two-minute version, Wessex shoes appeared in conjunction with McCaul Knitwear, while the one-minute film concentrated solely on Clarks, the soundtrack featuring ‘Big Beat Boogie’ by Bert Weedon. In the February 1960 issue of Clarks Comments, Stanley F. Berry, the Clarks advertising manager, explained the rationale:

There are two fields in which the young dominate: the Cinema, and Popular Music through the medium of gramophone records. The Rank people, after much research, claim that they can now produce a predestined top ranking disc based on well-proved formulae, and that film advertising associated with such music, without words, is likely to be more effective with young people than conventional cinema advertising.

The commercial was shot at Elstree Studios, with a roof-top set designed by the art director Cedric Dawe, and the action – featuring dance sequences performed by members of the Cool for Cats troupe, who had been a big hit on ITV – was choreographed by Dougie Squires. Squires had made his name on Chelsea at Nine, a television series starring Billie Holiday, and on the BBC’s On The Bright Side, made famous by Stanley Baxter.

Even more striking advertisements would follow. In the summer of 1964, two television commercials went on air with a James Bond theme. They were produced by Terence Young, who had worked on From Russia With Love, and the Bond-style music was arranged and conducted by Malcolm Mitchell. The idea of these two commercials – which were shot mainly in Palmers Green in London – was to remind viewers of Clarks’ fitting service and what became known as its ‘No Time Limit’ guarantee.

In a similar populist vein, Clarks provided Honor Blackman with her shiny thigh boots and other footwear that she wore in the role of leather-clad Cathy Gale in ITV’s The Avengers series, which regularly commanded an audience of 6 million on Saturday nights. And in 1967, Clarks hosted the BBC’s Any Questions live from its Plymouth factory, when the panel, chaired by Freddie Grisewood – who was nearly 80 at the time and had been on the programme since its inception in 1948 – included Sir Gerald Nabarro, a flamboyant, handlebar-moustached Tory MP, and a future leader of the Labour Party, Michael Foot.

![]()

Compared with women’s shoes, little money was spent marketing the Clarks men’s range – because there wasn’t much of a range to market. But in 1962, Clarks bought the established men’s shoe manufacturing business of J. T. Butlin & Sons Ltd. This company, based in Rothwell near Kettering in Northamptonshire, specialised in mail order sales and had a sound reputation for the more formal men’s shoe market. This was a contentious acquisition because Clarks had always approached men’s shoes with a diffident air – making a mere 0.8 per cent of men’s shoes in the UK in 1959. But the decision may have been influenced by the fact that John Butlin, the managing director, was married to Honor Impey, a great-granddaughter of James Clark.

In 1941, Clarks had made men’s boots as part of its commitment to the war effort and shortly afterwards it experimented by subcontracting work to G. B. Britton & Sons in Bristol, hoping this might lead to a more concerted commitment to men’s shoes. But it never quite happened. In the 1940s, the board had concluded that G. B. Britton & Sons did not produce the quality of work that Clarks required – or, at the very least, a standard that could command the sort of prices necessary to justify a bigger investment in the men’s market. Prior to the purchase of J. T. Butlin & Son, Bancroft had considered a bid for an alternative Northamptonshire firm, Crockett & Jones, which also made men’s shoes, but this came to nothing.

Traditionally, it had been left to the factories in Ireland to manufacture most of Clarks’ shoes for men, particularly the successful ‘Flotilla’ range, which was first introduced in 1954 and then gained its own separate catalogue in 1958. By 1962, Flotillas supplied everything a man could need by way of footwear: ‘Brogues’; ‘Suedes’; ‘Casuals’; ‘Contemporaries’; and ‘Sandals’. Appropriately, the sales slogan for Flotillas was: ‘The City to the Sea’. Not until 1970 was the Clarks Flotilla range superseded by Craftmasters, City and Club shoes.

A touch of design class was introduced to Clarks’ range in 1963 with the appointment of Hardy Amies as consultant designer, a man whose other clients included the Queen and the Queen Mother. Amies, a Londoner born in Maida Vale, was 49 when he began working for Clarks and seemed in no doubt about his expertise. Speaking at an event organised by the Royal Society of the Arts, Sir Hardy, as he later was to become, said:

A dress designer is not just a frivolous person catering to the whims of rich women, but someone who, properly used, can play a part in the industrial life of this country.

His credits included a variation on the Chelsea Boot, elastic-sided shoes and slip-ons, and it was he who coined the phrase ‘the laceless look’. Amies was invited to share his vision with readers of the Courier in October 1964, advancing the cause of raised heels. ‘There are few men who would scorn at being an inch taller,’ he said, before stressing that ‘the shininess of well-polished leather is the best possible contrast to the mattness of a wool suit, still the basis for modern men’s dressing.’ He ended up deploring young people’s ‘disregard of grooming … an attitude of mind backed up by a shortage of domestics’.

Young people who met with Amies’ disapproval were not the natural customers of Peter Lord. They would be catered for later when Clarks bought Ravel, which targeted fashion-conscious young men and women with cash to spend on contemporary footwear. Peter Lord, regarded as the purveyors of sensible shoes, continued to grow. After opening for the first time in London’s Oxford Street in 1960, with a staff of 24, the chain’s 70 outlets were selling nearly one million pairs of shoes a year. The Oxford Street branch was competing with no fewer than 30 shoe shops on that street alone, but it did so with aplomb, its huge glass windows catching the eye of passers-by, and that same original site, within a few minutes’ walk of Oxford Circus Underground station, is still occupied by Clarks today.

A 1965 press advertisement produced during Hardy Amies’ stint as a consultant for Clarks.

In 1962, the British Shoe Corporation controlled around 2,000 of the UK’s estimated 14,000 shoe shops. British Bata, the biggest independent, had, by comparison, fewer than 300 outlets. But size was not everything. Clore’s British Shoe Corporation had its critics, not least because Clore himself had his critics – in growing numbers. Felicity Green, women’s editor of the Daily Mirror, wrote scathingly in the spring of 1963 about his cavalier style in what amounted to an open letter:

When you moved into the shoe business you obviously organised things in your usual efficient manner. No doubt your trusty accountants moved in first and, when they had things on a sound financial basis you proceeded to sell shoes scientifically as you might sell fish or saucepans.

The Sunday Times Contango column ran a piece headlined ‘The village shoemakers match up to Mr Clore’, which referred disparagingly to the ‘Clore colossus’ that had ‘squeezed out the smaller multiple chains’. It continued:

The Clarks – like the Frys and the Rowntrees and the Cadburys – are Quakers. And they believe in living in the heart of the place that their enterprise has created. Bancroft Clark’s house is in the middle of the village, where the buses stop, and the teenagers’ motor-cycles change gear. Nobody notices particularly when he drops into the social club or strolls down to the Post Office.

This idealistic account of life in Street ended with a quote from Bancroft:

The women’s magazines know nothing about style. It’s the little girls in short skirts showing their knees who change style. And we can’t let Mr Clore always see the changes first.

The Financial Times had warned a year earlier that it was in ‘manufacturing rather than in retailing that the biggest opportunities are to be found … retailers appear to have exhausted their opportunities for the time being’. Certainly, 1962 was a difficult year for all UK shoe retailers, but, despite the Financial Times’s foreboding, 1963 saw Peter Lord making a welcome recovery, with sales of £3 million. And the Financial Times would also be proved wrong about manufacturing as more and more footwear companies began to source shoes from overseas rather than making them in Britain.

Sourcing shoes from outside the UK – also referred to as resourcing – would haunt Clarks for many years to come. It’s easy to conclude that the company should have moved towards sourcing with greater speed, but buying-in footwear was utterly at odds with Clarks raison d’être as a shoemaker. The company’s whole culture and history were based on making shoes. Manufacturing shoes was not so much what Clarks did best, but what it did.

Even so, in 1960, Hugh Woods, who worked for Clarks Overseas Shoes Ltd, went to Italy and began sourcing ready-made shoes that retailed in Canada and North America under the Clarks name. Woods was acting with Bancroft’s full approval, but it did not go down well in some of Clarks West Country factories. In an interview in 2005 with Dr Tim Crumplin, Clarks archivist, Woods said that the

factory managers were incensed because nobody had ever bought foreign shoes and branded them Clarks. I was known as the Clarks Wop.

![]()

One of those who took up a post as sales assistant in Peter Lord’s Oxford Street branch in late 1966 was Roger Pedder, who, 30 years later, would become chairman of C. & J. Clark Ltd. Pedder read economics at the University of Liverpool, where one of his tutors was Dr Roland Smith, a future chairman of House of Fraser and a man who had close links with the then powerful Boot & Shoe Association. Smith knew people in high places at Clarks and helped Pedder get an interview in 1963 for a place on the graduate trainee scheme. Pedder was successful.

Clarks took on five graduate trainees each year, all of whom would spend their first week learning to make a pair of shoes from scratch. Bancroft was in the habit of picking one of these trainees as his personal assistant. Towards the end of 1963, he chose Pedder.

‘I used to pay the cook, the cleaners, the gardeners, arrange the family holidays, you name it,’ says Pedder. He adds:

Bancroft had an absolute dedication to the company in all its aspects. He was very much of his time, the master, but he was also inclusive and commanded a great deal of respect. He saw the business in the context of the international economy and he had a high ethical sense for what was right. He was straight talking but careful in his dealings with people, especially members of the family. But there was never any doubt who was boss.

One of Pedder’s early tasks was to drive down to Portsmouth in a van to pick up a trunk belonging to Sibella Clark, Bancroft’s daughter, who had returned to England after graduating in history and fine art from Swathmore College, just outside Philadelphia, USA. This errand involved opening the trunk for customs officers and rifling through Sibella’s personal belongings. Roger and Sibella had never met. Mission accomplished, Pedder returned to Street, where a few days later he did meet Sibella – and they fell in love. They were married in 1968 in a private ceremony in Bromley Registry Office.

Two years later, Pedder left Clarks. As he describes it:

Marrying the boss’s daughter was always going to cause complications, especially once Bancroft had retired. I had a lot of soul-searching to do – in fact deciding to leave was one of the toughest decisions of my life. I left to join British Home Stores but before doing so I had learned a lot about Clarks. I had worked my way up the retail side of the business and then became a buyer for half the women’s ranges. So I understood the business pretty well.

Which would come in handy when Pedder returned to Clarks in 1993 in entirely different circumstances.

![]()

The age of management consultants had arrived. In 1963, Tony Clark commissioned McKinsey & Co., which had offices in London’s St James’s Street, to produce a series of reports on the company. The first was in November of that year. It outlined in detail the responsibilities of each manager, making it clear to whom they were answerable and where their remit began and ended. It was a long, plodding document, which was followed a month later by an even longer one called ‘Adopting a Consumer and Customer Oriented Approach to Marketing Branded Footwear’. McKinsey’s covering letter to Tony Clark included a short section entitled ‘Major Conclusions’ which, when read today, appears neither major nor conclusive:

Opportunities to increase profitable sales volume exist on a variety of fronts. However, there is ‘no rabbit that can be pulled out of a hat’ to do this. Capturing these opportunities means changing many things. In short, Clarks is going to make marketing the competitive cutting edge of its business.

McKinsey had taken soundings from the trade and included vox pops as part of its Relations with Retail section. ‘Clarks is Clarks. They do what they want’, was one of the comments canvassed. Another was:

I’m sure they’re good craftsmen, but they’re living in the 18th century when it comes to realising that retailers are their partners – both of us have to succeed or neither of us will!

‘Why don’t they stop trying to brainwash us with what they want and find out what the facts really are’, was a third.

A main thrust of the McKinsey findings was that if Clarks was to meet its production and sales targets, it would have to consider introducing a second brand name or acquire another branded manufacturer which already had a substantial market share or owned a significant number of retail outlets. The crucial and unresolved question of Clarks expanding upon or limiting its unbranded operations fell outside the scope of McKinsey’s study. The report did, however, highlight other areas to be addressed. It was a long list that included:

• Clarks’ reluctance to exploit properly the mail order business;

• the urgent need to increase warehouse space;

• a proposal to introduce twice-weekly deliveries by road transport to key customers;

• separating in-stock and forward order inventory records;

• a provision for more flexible handling of orders from large customers;

• a revamped customer inquiries and complaints department;

• improved communications between Street and travelling salesmen (who were in the habit of making over-optimistic delivery promises);

• a greater onus on factory superintendents being held responsible for keeping their word on production dates.

In other words, the consultants were advocating wide-reaching reforms.

It was also suggested that Clarks Ltd should be divided into three separate divisions – women’s, children’s and men’s – a move which Bancroft said would ‘release new management energies and powers … taking the lids off people and letting them get on’. This and several other of the recommendations were acted upon, and within twelve months Clarks had made and dispatched 10 per cent more shoes, with profits up by 20 per cent. The Bullmead warehouse, which had been built in 1954, doubled in size in 1964 and the adjoining Houndwood site in Street was pressed into service, both of which had an immediate impact on the wholesaling and distribution side of the business. In the past, when most of Clarks shoes were made in Street, distribution was mainly by train from Glastonbury station (now defunct), but this had proved far too slow and inflexible for busy retailers. Consumers wanted their shoes immediately and held retailers to account by shopping elsewhere if they could not walk away with what they required.

Clarks itself now had 100 Peter Lord shops, and during 1964 the company paid more than £1 million for the Wolverhampton-based family firm of Craddock Brothers, with a chain of 24 outlets in the Midlands and North West. Reginald Hart, managing director of Peter Lord since 1937, retired and was replaced by Eric Gross, a non-family member, who had joined the company shortly after the Second World War.

The Bullmead warehouse, built in 1954, was doubled in size ten years later as a result of McKinsey & Co.’s reports and recommendations.

Another McKinsey report came out in the summer of 1965, which was circulated to all managers. It emphasised the importance of a proper chain of command, described as ‘line-staff relationships’. Bancroft’s cover note made the point that ‘in all main aspects’ the report was as prepared by McKinsey, but, he added: ‘I have altered it only as necessary to fit into the organisation structure which we adopted at the end of May in place of the one McKinsey’s proposed.’

![]()

England won the World Cup in 1966 (with the team’s off-field suits designed by Hardy Amies), but there was not much else to celebrate. Harold Wilson’s Labour government had been returned to power in March with a slightly increased majority of 97 and was faced with a balance of payments crisis. The pound was devalued, a wage freeze put in place and an unpopular Selective Employment Tax introduced, designed to raise money from the service sectors in order to subsidise manufacturing. James Callaghan, the chancellor of the exchequer, introduced a Corporation Tax at the rate of 40 per cent.

Clarks was not immune to the nation’s economic troubles, which were fuelled by the growing restlessness of the trade unions. In 1966, an agreement was reached between the Shoe Manufacturers Federation and the National Shoe Trade Union to reduce the working week further from 41½ to 40 hours, while increasing holidays by seven days to 4½ weeks. This would cost Clarks an additional £250,000 a year – or an extra 5d. for each pair of shoes it made.

In the same year, two factories were closed: St Johns in Bridgwater and Northway in Midsomer Norton. And there were redundancies in others: 22 at Minehead, 27 in Street and 51 in Plymouth. A further 150 workers lost their jobs in November across the C. & J. Clark businesses. A spokesman was quoted in the Daily Telegraph of 16 August 1966 as saying:

We have had to cut back our plans for expansion, particularly for women’s shoes. We have taken a long and careful look at our overheads and pruned them wherever possible.

The price of raw hides and skins for uppers was rising, but for its soles Clarks was by now using very little leather. In the 1960s, the big breakthrough in soling was the development of polyurethane (PU) compounds, which earned Clarks the respect of – and a considerable amount of money from – the wider shoe-making world. Even back in the early 1950s it had been proposed that the company should appoint a specialist organic chemist to develop PU. This never happened, but fortunately a letter towards the end of 1962 from Michael Mayer-Rieckh, a friend of Peter Clothier, and a member of the founding family of the Humanic Shoe Company in Graz, Austria, galvanised Clarks’ interest in PU soling. This letter offered an introduction to Dr Oskar Schimdt Jnr, who had developed a new process for moulding plastic soles on to normal footwear.

A company delegation was dispatched to Austria in January 1963 to investigate the Schimdt process. Its members were impressed. Schimdt then came to Street and the company set in place a formal agreement between him and C. I. C. Engineering, which was part of Avalon Industries. But the clock was ticking, with competitors such as Bata and Wolverine launching their own concerted assaults to exploit the latest technical advances in soling.

A Peter Lord shop interior in Stafford in the 1960s, showing the sales desk area, with fitting stools in the foreground.

It was not until March 1969 that a prototype PU moulding machine was commissioned at the Minehead factory, but by 1972 there were Rotary or what was called In-line machines in six Clarks factories, all using C. I. C. moulds. Chemical supplies mainly came from Avalon Chemicals based in Shepton Mallet and specific compounds were developed for individual factories. At one time, twenty different compounds were being produced, each with subtle differences of colour, texture and flexibility.

Over the next decade, huge investments were made in PU for factories specialising in casual products such as men’s polyveldt and sandals, women’s Clippers and Pop-ons and children’s hardwearing shoes for school. PU was a fundamental factor in sustaining Clarks’ image as a major player both nationally and internationally, and C. I. C. was selling its compounds to shoe manufacturers around the globe.

The physical properties of PU soles as experienced by consumers were compelling: lightness, softness, flexibility, resilience (shock absorbency) and durability. In essence, a dream product to market. Some factories with PU machines were working two and three shifts, such was the level of demand for their products.

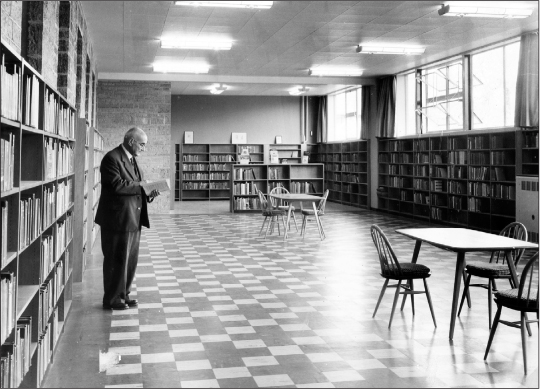

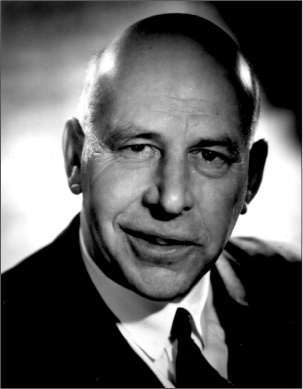

Daniel Clark, Bancroft’s eldest son, became managing director of Clarks Ltd in 1967.

![]()

Bancroft Clark – known always as ‘Mr Bancroft’ – retired in August 1967 but remained a powerful presence for another quarter century, living just long enough to see Clarks stumble through its darkest hour in 1993. His only official role in the business after standing down was as chairman of Street Estates Limited.

Bancroft had worked in the business from 1919 to 1921 before going up to King’s College, Cambridge. After taking his degree, he rejoined the company in 1924 and then succeeded his father, Roger, as chairman in 1942. He occupied that post for 25 successive years, during which he led Clarks through a period of unprecedented growth, both at home and overseas. Comparisons with the period immediately after the war and with 1967, the year he retired, are instructive. Turnover increased from £1.3 million a year in 1946 to £40.4 million in 1967; there were 1,906 employees in 1946 and 14,398 in 1967; Clarks was making 1.4 million pairs of shoes in 1946 and 18.5 million in 1967. There were 175,000 ordinary shares in 1946, compared with more than six million in 1967.

The retirement of Bancroft coincided with that of Arthur Halliday, whose firm in Ireland, John Halliday & Son, had joined forces with Clarks in 1937.

These two high-level departures led to wider changes. Tony Clark became chairman of C. & J. Clark Ltd and Peter Clothier was made managing director. Daniel Clark took over as managing director of Clarks Ltd, the branded shoemaking operation, and Eric Gross was appointed managing director of both Clarks Overseas Shoes Ltd and, temporarily, of the Unbranded Division. Jan Clark, Bancroft’s second son, was promoted to the board and made responsible for C. & J. Clark Retailing.

Following Bancroft’s retirement, the decision was taken to make Clarks Shoes Australia Ltd an independently managed subsidiary of Clarks Overseas Shoes Ltd. Foster Harrison, who had been factory manager of Alma Shoes, the Australian manufacturer bought by Clarks, was appointed the first managing director of Clarks Shoes Australia Ltd and became a member of the main C. & J. Clark board. The other directors were Stephen Clark (company secretary) and John Frith (financial controller). In 1967, the nine-man board comprised six family members and three non-family members.

![]()

Wherever you looked there was change and expansion. Early in 1967, Clarks acquired a 51 per cent interest in Mondaine Ltd, a privately owned company which operated at the high-fashion end of the shoe market, trading under the names of Ravel, Mondaine and Pinet. Altogether, Mondaine Ltd had some 50 shops in London and the Home Counties, with a turnover of £2 million a year. Four of its stores were in Bond Street and one was in Carnaby Street. Then, less than a year later, Clarks added a Scottish shoe group called Bayne and Duckett to its portfolio, which came with 60 retail outlets in and around Glasgow and Edinburgh, including Baird’s, a well-known bootmaker.

In 1968, Clarks acquired the Australian Shoe Corporation and opened a new factory in Melbourne, of which it owned the freehold. A year later, in 1969, a new factory was built in Adelaide expressly for the production of Hush Puppies, a casual shoe made with supple suede uppers and lightweight crepe soles. Created in 1958 by the Wolverine shoe company in Rockford, Michigan, Hush Puppies derived their name from the southern American dish of fried corn balls that were supposedly thrown to barking dogs to quieten them down.

In New Zealand, a new children’s factory was opened at the aptly named Papatoetoe, outside Auckland; the minister of customs cut the ceremonial ribbon. A small shoe manufacturer called The Happy Shoe Company was bought in Ghana, making 2,000 pairs of crepe-soled sandals a week. Meanwhile, in America, there was a welcome turnaround in 1969 with the wholesaling company, Clarks of England Ltd, recording sales up by 50 per cent on the previous year. And Clarks’ position in relation to the rest of Europe was bolstered by the opening of new offices and warehouses in Denmark and Sweden, in addition to the existing ones in Paris and Zurich.

Back home, at the beginning of 1969, Clarks bought Trefano Shoe Ltd, which specialised in comfortable women’s shoes. This company, with 371 employees, operated near Tonypandy in the Welsh Valleys and came with two big advantages: it was in a ‘designated development area’ that benefited from government grants and rebates, and the new Severn Bridge, opened by the Queen in September 1966, made access to and from Wales much easier for heavy goods vehicles.

As Clarks expanded by opening new factories it also sought to increase the efficiency of its operations. Raising productivity and lowing costs were what occupied the minds of factory superintendents and their deputies.

As Eric Saville, who joined Clarks as a management trainee in 1960 after studying classics at Cambridge University, explains:

I spent a lot of my time with a stopwatch … The piecework system was central to everything. The harder you worked, the more cash value you had. It was hard work. In fact, it was the closest thing to slave labour that I ever saw.

After completing his training, Saville became head of works study in the Grove factory in Street before moving from one plant to another as a deputy superintendent and then becoming superintendent (factory manager) of the sandals factories in Yeovil and Ilminster. As he describes it:

I never seemed to stay anywhere long enough to feel I had achieved something. Finally, I said ‘no’ when they wanted to move me back to Street as a superintendent. Tony Clark tried to persuade me and said: ‘I thought you liked a challenge, but clearly you don’t.’ Eventually, I did what I was told, but left a few months later and joined a management consultancy firm in London. After that, I was offered jobs by other companies but came to the conclusion that I had seen nothing that I liked as much as Clarks.

So Saville rejoined in 1970 and spent the rest of his working life at Clarks, including three years in Australia after Raymond Footwear Components was bought to make heels, soles, lasts, insoles, stiffeners, wedges and other bits and pieces vital to shoemaking.

Saville, who retired in 1995, had nothing but admiration for Clarks:

Clarks was light years ahead of others in terms of industrial relations … Each factory had its own factory council and would send representatives to the Company Council in Street, which met two or three times a year. This was a chance to air any grievances direct with members of the board. You could say anything you liked and would be heard.

In 1971, there were further increases in warehouse space at Bullmead, with the provision of an additional 48,000 sq ft built on three levels. The Clarks raw material warehouse at Cowmead also underwent modernisation, and on the Houndwood site a new 10,000 sq ft maintenance garage was opened, complete with automatic car- and lorry-washing machines to service the company’s 50 trailers and 100 cars. The improvements to Houndwood cost more than £1 million.

The fifth generation of Clarks was about to take over running the business, but cracks were beginning to appear. A drop in profits in 1972 was described by Tony Clark in his annual Chairman’s Report as ‘considerably below what we budgeted to achieve’. On sales of £94,169,000, the profit before tax was £4,875,000, down from £5,241,000 on the previous year. And the figures would have been much worse had it not been for the sale of surplus land owned by Street Estates Ltd, whose results were now incorporated into the accounts of C. & J. Clark Ltd.

Competition in the fashion shoe sector was relentless – from Italy, Spain and, increasingly, Brazil – while, at the cheaper end, shoes were pouring into the UK from the Far East, particularly Pakistan and Malaysia. Exports to traditional markets such as Nigeria, Zambia, Malawi, Bermuda, Nassau, Jamaica, Trinidad and Hong Kong were just about holding up, but increases in the costs of shoemaking in the UK were starting to affect Clarks’ competitiveness and there was bad news from the Unbranded Division, which, in 1972, posted ‘disastrous’ results.

It was time to engage the services of another firm of consultants. The Boston Consulting Group, which was based in New Zealand House, in London’s Haymarket, spent months examining various aspects of Clarks’ business, after which Tony Clark told shareholders:

We found their reports on various aspects of the business and the opportunities that they saw for growth interesting and stimulating, and certainly helpful in our forward strategic planning.

In truth, some of the Boston Consulting Group’s conclusions had made for uncomfortable reading. Its report warned that:

… although Clarks Limited is an effective manufacturer of shoes in a high income country, in the context of future world supply patterns this will not be a base for future growth.

Echoing publicly what some senior members of staff were thinking privately, the Boston Consulting Group urged the company to ‘reduce its involvement in the peripheral activities that neither contribute materially to its strength nor add to its profitability’. Specifically, it described the unbranded side of the business and some of the shoe component operations as ‘unnecessary distractions’. Its recommendation under the ‘Unbranded’ heading, amounted to one word: ‘Withdraw’.

This, apart from a small factory in Ireland which continued for a number of years making cheap, unbranded women’s fashion shoes, was achieved by the end of 1973. Wansdyke reverted to making branded shoes, London Lane was sold back to its original East End owners and A. & F. Shoes went into voluntary liquidation.

The Boston Consulting Group went on to suggest that Avalon Engineering should ‘phase out of the manufacture and sale of machines’ and wrote at length about the pros and cons of Peter Lord operating as an independent multiple. But its most telling observation, and one that would take many years for the company to act upon, addressed the core of Clarks’ business – the production of branded shoes. It stated simply: ‘Overseas sourcing for Clarks Ltd, from a low labour cost country, or on an owned basis, should be given high priority.’

Any worrying internal reflections on Clarks’ future were, to an extent, shared by outside commentators. Prudence Glynn, a fashion writer for The Times, penned a long feature in April 1972, which began:

I have always thought of Clarks as the Sainsbury’s of the shoe business: equally dedicated to producing best quality for the best price, vastly respectable, family dominated, paternalistic and hung about with an aura of rectitude.

But then she went on to criticise many of the most popular ranges such as Spectrum, Trumps, Nova and Skyline, and concluded how she preferred to have Italian brands in her cupboard. She went on to say:

I think that right across the British shoe industry there is a need for a much higher standard of design. I should really rather buy native shoes than Italian imports, gentlemen. In the meantime, Clarks gesture to more interesting fashion is very welcome. It is definitely the moment for the carrot, I feel, not the stick.

Peter Clothier, one of those who had striven to make Clarks more fashionable and more appealing to younger consumers, retired in 1973 at the age of 63 and was replaced as vice chairman and managing director by Daniel Clark, Bancroft’s oldest son. Clothier had joined the company in 1927 and became a towering figure not just in Clarks but in the wider shoe world, serving as president of the British Footwear Manufacturers Federation and gaining a reputation for his informed lectures on the shoe trade. A special issue of the Courier was produced to mark his retirement, including a personal tribute from Bancroft and a long summary of his career by Tony Clark, his friend and colleague of more than 40 years. Clothier, whose two sons, Anthony and John, joined Clarks in the 1960s, said in a farewell message:

We have to be aggressive and ingenious in creating new products and new wants, and bring these to the public – never forgetting that the customer is the master we must satisfy.

The customer – and the public at large – was given a chance to explore some of Clarks’ history when the Shoe Museum opened in Street on 14 March 1974. There had formerly been a museum of sorts, housed in Crispin Hall on the High Street, and not everyone was keen that space should be found for a new one in the main headquarters building. Stephen Clark was firmly in favour and he was largely responsible for overseeing the museum, drawing upon the archives and making sure that a collection of fossils of ichthyosauruses (extinct marine animals) and a fine selection of stuffed birds were brought safely to their new home, along with shoes dating back hundreds of years. The museum remains today in its prominent place – though the fossils have moved on – and in 2011 was the subject of a news item on BBC Breakfast when a group of Chinese tourists included it in their itinerary of Britain, moving seamlessly from the Tower of London to Stonehenge to Street. The archives were relocated to a new purpose-built site in 2012 and are one of the most extensive and well-organised of any company in Britain if not the world.

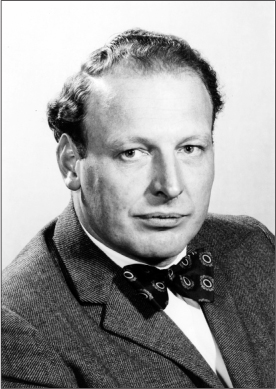

Peter Clothier, a grandson of William S. Clark, worked at Clarks for nearly sixty years, culminating in six years as managing director between 1967 and 1973.

In 1974, Miss World came to call – not to see the museum but for a special fitting of a pair of Barbarys, part of the relaunched Country Club casual range. ‘Gee, they’re wonderful and a perfect fit’ said Marjorie Wallace, who hailed from Indianapolis, USA, as the Redgate factory manager, David Heeley, slipped the tan and white shoes on to her silky feet.

Miss World was visiting Britain’s sixth-biggest private company and now the largest shoemaking concern in Europe. Clarks employed almost half the 8,000-head population of Street and, despite speculation from time to time in the press, there were no plans to float the company, and no intentions to change its family-based management structure. Some sections of the media found this perplexing. An article in the Observer towards the end of 1974 spoke of a:

discernible attitude of caution towards this curious family, which, over the years, had made such a spectacular amount of money in such an unspectacular way.

Grappling with the culture of Clarks became something of a preoccupation for newspapers. The Sunday Times was intrigued by the lack of company cars and the way the Bear pub, opposite the head office, was still dry. An article by Allan Hall in that paper’s Atticus column on 17 March 1974 carried the headline ‘How not to spend a fortune’, and was based around a rare interview with Tony Clark who was quoted as saying:

If you said we were millionaires, I should think we’d all sue you for libel … I suppose the next generation may be different but I doubt it … I suppose I’m a bit different from our earlier generations. I have a drink. But I don’t smoke in the office until 5 o’clock. We have a rule in here that there’s no smoking and it’s worth it because we get a reduction on the insurance premiums.

Hall noted that Tony’s office was sparsely furnished and had lino tiles on the floor. There was no art on the walls and his desk was ‘of the school room sort’. The company car issue was raised during the interview.

‘As a matter of fact, nobody has a company car,’ said Tony. He went on:

You see, in a family business where five of the nine directors are all Clarks you have to work and get on together. You avoid situations that create jealousies and frictions. We have always said you should pay people for what they do rather than set up these standards of what kind of office they have and what kind of car they drive, according to which chair they are sitting in. What do I want with a luxurious office?

Shortly after that interview, and within twelve months of Peter Clothier’s departure, Tony Clark himself retired as chairman of C. & J. Clark Ltd at the end of August 1974, giving way to his 41-year-old cousin, Daniel, who decided that, like his father (Bancroft), he would combine the role of chairman and managing director. Daniel had studied engineering at Cambridge University and had joined the company in 1954, taking up his first main job as superintendent of Shepton Mallet four years later. He was interested in matters of the mind, but at the same time was practical, with a passion for how things were made. He was warm, cultured and unfailingly courteous. He was hard-working, well-liked, experienced and greatly respected. But his father was a hard act to follow.