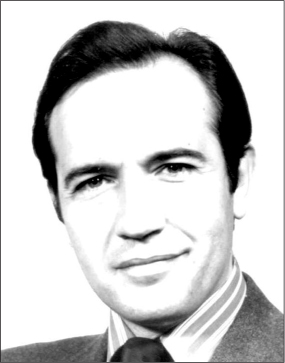

Daniel Clark became chairman of Clarks in 1974, shortly before the 150th anniversary celebrations the following year.

ALCOHOL WAS MOST DEFINITELY SERVED at the 150th anniversary celebrations of C. & J. Clark Ltd in June 1975 – and lots of it. There were parties galore to mark this particular landmark, both in Street and in London, where the festivities handily coincided with London Shoe Week. There were three lunches and a dinner in Street alone during the week starting 16 June 1975, all held in a huge marquee erected on lawns in front of the Grange, overlooking the main headquarters building.

The new chairman, Daniel Clark, made four separate speeches, each tailored to his particular audience. The ‘Inaugural Lunch’, as it was called, held on Wednesday 18 June 1975, was attended by the great and the good from the southwest, including the Conservative Member of Parliament for Wells, the chairman of Somerset County Council, the Mayor of Glastonbury and the chairman of the Street Parish Council. The chairman of Mendip District Council was there, too – Ralph Clark, who was chairman of the Clarks subsidiary, Avalon Industries. Civic leaders were joined by leading lights from the British Footwear Manufacturers Federation, the National Union of Footwear, Leather and Allied Trades and other associated organisations. Clarks’ main competitors were included as well. In fact, a senior executive of Startrite, a rival manufacturer of children’s shoes, made a speech on behalf of guests, and even Harry Levison from the British Shoe Corporation was asked along.

Daniel Clark became chairman of Clarks in 1974, shortly before the 150th anniversary celebrations the following year.

The next day, a Thursday, some 500 Clarks pensioners walked into the tent for lunch and filed out again a couple of hours later, each holding a little leather wallet containing a cash voucher. The evening do on the Friday was for all employees with 25 or more years’ service under their belts. Wives and husbands were invited only if they too had chalked up a quarter of a century at Clarks. Maurice Burt, the factory worker who had missed the 125th anniversary party because he was unattached at the time and felt uneasy going on his own, attended this one and, although now happily married, was perfectly content to leave his wife at home:

It wouldn’t have done to have the wives there, not at all. It was quite a party, I can tell you. I think I must have got home about 4 am and there can’t have been many steady heads in the morning. Whenever you put your glass down or if it was getting near empty someone came along and filled it up again. There was no dancing or anything, but everyone found a way to let off steam.

The menu was a 1970s classic: ‘melon boat’ to start, ‘dressed Scottish salmon’ with mint new potatoes, garden peas and a green salad to follow, rounded off with fresh strawberries and cream. Petit Chablis and Côte de Beaune-Villages flowed liberally. Bill Graves, a non-family member of the board, gave the main address, to which Cyril Gifford, one of the firm’s plumbers, whose family had been associated with Clarks for decades, replied on behalf of the whole workforce.

An altogether more sedate lunch took place on Saturday for shareholders. This was followed by a tour of the attendees’ choice – either the historic buildings of Street or the churches of Somerset. The former included an inspection of two modern sculptures, Diamond and Steps, both by Philip King, which had been unveiled earlier in the week on either side of the Grange Road approach to the factory.

Daniel Clark used the anniversary as an opportunity to reiterate some key values. In one of his speeches, he said:

The Quaker upbringing and tradition of the founders of the company continue to inform the way we think about the business and its problems, and the sort of business we want to be; the conditions under which we employ people; our produce and services, and their integrity and usefulness to the community. Whether we think about the product or the way it is promoted, or the people who produce it, we want everyone to be proud to be associated with the company.

In London, Lance Clark, managing director of Clarks Ltd, the branded footwear division, was the host and keynote speaker at two dinners held at the Europa Hotel off Oxford Street, only a couple of days after an IRA bomb had exploded outside the nearby Portman Hotel, injuring three passers-by. At least 1,000 people attended, including the television personality Judith Chalmers (a well-known fan of Clarks), the actress Adrienne Corri, who appeared alongside Peter O’Toole and Richard Attenborough that year in Otto Preminger’s film Rosebud, and the actor Patrick Mower, who many years later would become a stalwart of ITV’s soap opera Emmerdale. A special anniversary exhibition was put on at Clarks’ London offices in Berners Street, to which the press was invited, along with those attending the Europa Hotel dinners and others associated with the shoe trade. The exhibition consisted of a visual history of shoemaking set to piped music from the 1930s.

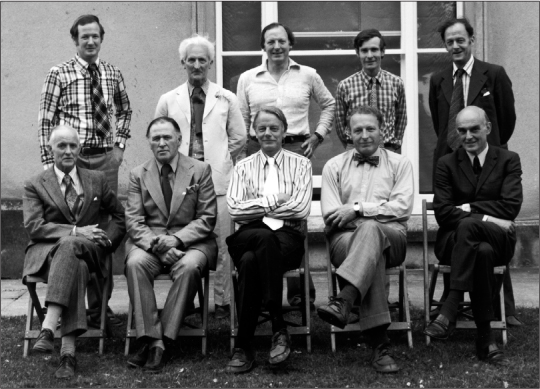

Key figures at Clarks pose for a photograph to mark the 150th anniversary celebration in 1975. Back row, left to right: Lance Clark, Stephen Clark, Jan Clark, William Johnston and Ralph Clark. Front row, left to right: Foster Harrison, A. W. (Bill) Graves, Eric Gross, Daniel Clark and John Frith.

In sharp contrast, there was none of this fanfare and no mood music to mark the closure of Clarks’ Yeovil factory four months later in October 1975, when nearly 100 workers lost their jobs. This factory, along with several others, had been operating on a four-day week for a number of months as the country reeled from one economic crisis to another. Cabinet papers released in 2005 under the 30-year rule reveal that the Labour prime minister, Harold Wilson, was warned by his energy minister, Lord Balogh, that Britain’s economy faced ‘possible wholesale domestic liquidation’ if inflation and unemployment continued to rise. The then industry secretary, Tony Benn, at odds with the chancellor, Denis Healey, pressed Wilson to introduce quotas and higher tariffs on imports, along with cuts in defence spending and selective help to industry – but a cap-in-hand approach to the International Monetary Fund for a £2.3 billion bail-out was the course the beleaguered government took.

Britain was the so-called ‘sick man of Europe’, limping towards what would become the ‘winter of discontent’ in December 1978. There was talk of ‘lame duck’ industries and how the country had been brought to its knees by the ‘British disease’. Skinheads in ‘bovver boots’ threw sharpened pennies at opposition fans at football matches; new ‘brutalist’ post-war tower blocks became ghettos of antisocial behaviour; and the prospect of public spending being cut by some £3 billion was obscuring any light at the end of the economic tunnel. Many high earners had decamped overseas to avoid being taxed at the top rate of 83 per cent.

While politicians argued and the trade unions stockpiled their options amid escalating labour unrest, housewives took direct action. A Clarks survey in 1976 showed that hard-up mothers weren’t bothering to buy back-to-school shoes for their children – and this resulted in a 15 per cent drop in sales for the company. Suddenly, feeling the pinch was a common affliction among UK shoe companies. Workers at K Shoes in Kendal, in the Lake District, were on shortened weeks, as they were at Norvic in Norwich, and at the Down shoe factory in Belfast.

Making matters worse were the imports of cheap shoes flooding into the country at an increasing rate – although this of course was welcomed by independent retailers anxious to keep their buying costs down. Annual shoe imports averaged 80 million pairs between 1971 and 1975, rising to 97.5 million in 1976. This meant that by the end of 1976, 40 per cent of all shoes sold in the UK were made abroad.

There may have been a reluctance to source or manufacture shoes offshore – and certainly it was never given the ‘high priority’ advised by the management consultants – but there were flurries of activity in this direction. In 1978, a company called Atlas Shoes, in Nicosia, Cyprus, was looking for an investor and Clarks took a 51 per cent share. The plan was for Atlas to produce 150,000 pairs of children’s shoes a year, but by 1979 this target had been re-adjusted, with Atlas making around 90,000 pairs of men’s sandals instead. John Willets, who was in charge of Atlas, wrote a note to Bernard Harvey, a long-term factory manager back in Street, saying that any other lines at Atlas were merely ‘small bits and pieces with heavy development costs, quality problems etc – a formula for disaster’. Atlas closed in 1983.

Closer to home, towards the end of 1975 the company made its first big move into the European Economic Community – which Britain had joined two years earlier during the premiership of Edward Heath – by buying an 80 per cent stake in the French retail chain France Arno, which had 48 shops in major cities, including Paris. It sold mainly women’s shoes, but none were from the Clarks range.

Jan Clark, now managing director of C. & J. Clark Retailing, told the Financial Times that the acquisition offered scope for further investment and expansion ‘and opportunities for the export of footwear from Britain’. Those opportunities never materialised.

A far more significant decision was taken two years later in 1977 when Clarks paid £14 million for the publicly listed Hanover Shoe Company and its subsidiary, Sheppard & Myers, in the USA. The directors felt expansion into America was essential, not least because, according to the minutes of a board meeting in 1976, it was an opportunity to operate without being impeded by ‘left-wing policies’ in the UK, where Labour had been returned to government in 1974. Clarks had enjoyed some success in America and it was felt that a medium-sized acquisition would consolidate the company’s position on that side of the Atlantic, especially one that came with an established retail arm.

Such was the scale of this venture that there was speculation in the media about it being a precursor to a public flotation by Clarks, although, in fact, it led to the removal of Hanover’s share quotation on the US Stock Exchange.

The Hanover Shoe Company had been founded in 1899, specialising in high-grade, middle-priced shoes known in North America as ‘dress shoes’, with proper, welted leather soles. It had shops in some of the best malls in the country and it complemented Clarks, which was known primarily for its casual rubber-soled footwear. The board was impressed by the conservative and honest nature of its way of doing business. Based in Hanover, Pennsylvania, it had three leased factories in West Virginia and ran 240 of its own Hanover-brand shops across the USA.

Clarks had been looking for an opportunity to invest in the USA for some time, and with extra urgency after Florsheim, a retailing giant also specialising in formal shoes, gave Clarks an ultimatum over its prices towards the end of 1974, threatening to renege on its £1 million annual order. Florsheim also rang alarm bells in Street when it began sourcing cheaper versions of Wallabees from Czechoslovakia.

Following the Hanover Shoe Company acquisition, Clarks paid some £3.5 million for the Bostonian Shoe Company a year later in 1979 at a cost of some £3.5 million. Bostonian, a shoe manufacturer and retailer based in Whitman, Massachusetts, was part of the Kayser-Roth Corporation, a subsidiary of Gulf & Western. Jan Clark, who had moved in 1978 from heading up retail in the UK to taking charge of Clarks in North America, was keen to gain more outlets in which to sell Hanover shoes, and the Bostonian deal gave him nearly 100 of them. It was a bold strategy, but one that brought with it a new set of problems because Hanover and Bostonian sold the same kinds of formal footwear at a time when the commercial wind was blowing in the opposite direction, towards more casual shoes. Clarks profits in the USA declined by 10 per cent in 1978 and the position worsened over the next two to three years. But it did mean the company had a presence in America, a commercial base from which it could manoeuvre over the next few decades. Today, the American market is crucial to Clarks, accounting for approximately 40 per cent of its business, and many of the current Clarks stores in the US at one time had either Hanover or Bostonian above the door.

There were, however, some senior directors who worried that Clarks had moved from being a competitive branded shoe manufacturer to an investor in other companies’ inferior shoe manufacturing and retailing.

![]()

Judging the market in the 1970s was a formidably hard task. Social mores loosened, fiscal budgets tightened. Roy Jenkins, a liberal-minded home secretary in Harold Wilson’s last government, had set out to build what he called a ‘civilised society’ by abolishing the death penalty, decriminalising homosexuality, legalising abortion, relaxing the divorce laws, and reforming theatre censorship. Choices abounded. In the world of shoes, platform soles, as worn by Abba and Gary Glitter, were all the rage, with the likes of David Bowie, Marc Bolan and Elton John doing their bit in the cause of ‘glam rock’. But it wasn’t all glossy, as Noddy Holder’s Slade and the Bay City Rollers clunked around at the top of the music charts in working men’s boots and shoes, and on nights out, young men and women were often wearing the same kinds of footwear.

Sporting platform shoes didn’t mean you had to look like members of Kiss (the American band that was the inspiration for the satirical film Spinal Tap) to get noticed. Barbara Hulanicki, the Polish-born fashion designer, produced her Biba-trademark range to great critical acclaim, recapturing some of the elegance of Salvatore Ferragamo’s platforms of the 1930s. Clarks’ foray into this particular market produced the 1976 Andy Imprint Rangnoddye, with three-inch stacked heels and crepe rubber soles, retailing at £11.99. These were more Barbara Hulanicki than Noddy Holder – but at a fraction of the cost.

Then, just as it was safe to dispense forever with kipper ties and loon pants, along came the punk scene, which did its best to reflect the national gloom. Angry music by the likes of the Sex Pistols and the Clash brought with it ripped clothes held together by giant safety pins, spiky red hair and snarling attitudes utterly at odds with the repressed, genteel culture of Upstairs Downstairs, the phenomenally successful London Weekend Television series about an upper-class Edwardian family and their servants, which ran to 68 episodes in the 1970s.

The footwear of choice for punks was Doc Martens, especially the Eight-Eyelet 1460 model, which took its name from the day, month and year of its creation by R. Griggs Group Ltd, a respectable Northamptonshire shoe manufacturer which had bought the patent rights from Klaus Martens and his friend Herbert Funck.

Clarks gave punk culture a wide berth. But a far more perplexing challenge – and greatly more damaging in the long term – was the rise of the sports shoe, or trainer.

In 1895, Joseph Foster, from Holcombe Brook, a small village north of Bolton in Lancashire, founded a shoe company called J. W. Foster & Sons, which eventually ended up as Reebok International Ltd, now a subsidiary of Adidas, the German sportswear company. His big idea was to create a spiked running shoe, which British athletes would wear at the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris, famously captured on the big screen in the 1981 film Chariots of Fire. It wasn’t until 1960 that two of Foster’s grandsons rebranded the company Reebok, so named after a type of African gazelle. Then, in 1979, Paul Fireman, an American partner of an outdoor sporting goods distributor, spotted Reebok at a trade show and secured the North American distribution rights. Within months, Reeboks were selling for $60 a pair, making them the world’s most expensive running shoes.

Except that they weren’t just running shoes. Like Nike’s Waffle trainers, they started as running shoes but ended up as everyday casual footwear and a fashion statement at the same time, a phenomenon that must have astonished their track-suited inventors, Blue Ribbon Sports. Blue Ribbon, the predecessor to Nike, had emerged from the northwest American state of Oregon, where Bill Bowerman, a talented running coach, reportedly poured rubber into his wife’s waffle-making machine as part of his search for a comfortable shoe for middle-distance athletes. Along the way he paid an art student $35 for the Nike swoosh, one of the most famous trademarks on earth. Nike, named after the Greek goddess of victory, broke away from Blue Ribbon Sports in 1972 and went on to become a global sensation, helped by its sponsorship of a young Michael Jordan, the American basketball player who had the Nike Air Jordan trainers named after him.

Clarks responded to the trainer revolution by developing a range of its own called ‘Clarksport’, which included two general training shoes (‘Jetter’ and ‘Jogger’); shoes for squash, tennis and badminton (‘Supreme’, ‘Spin’ and ‘Service’); shoes for golf (‘Golfer’ and ‘Golf Ace’); a shoe for sailing (‘Fastnet’) and a shoe for bowls (‘Bowler’). Most of these were made in the Minehead and Weston-super-Mare factories and at Dundalk, in Ireland, one of several factories known for its extensive research and innovative design techniques. Some Clarksport products used the new Polyveldt compound soling that was hard enough to withstand rigorous stresses and strains, but still felt comfortable for the wearer.

On a baking hot June day in 1976, a special men’s division sales conference was convened in Street to launch Clarksport. Victor Jenkins, Clark-sport brand manager, began proceedings by saying, ‘Morning, sports, welcome to the fantastic new world of Clarksport!’ and then presented the range, using members of staff as models, who hopped on to the stage carrying accessories appropriate to the shoes they were wearing: a golf club here, a tennis or badminton racquet there. Jenkins reminded everyone that more and more people were joining sports clubs and that the sale of squash racquets was increasing by 12 per cent every year. Watched and supported by Neville Gillibrand, the men’s division marketing manager, and by Malcolm Cotton, who was overall head of Clarks men’s division, Jenkins pointed out that some Clarks retailers were expecting sports shoes to offset any downturn in the sale of more formal footwear.

‘We should be able to produce premium products with our 150 years’ shoemaking experience and our expertise in shoemaking in every field,’ he said, before handing over to Dr Vaughan Thomas, a leading sports consultant and director of physical education at Liverpool Polytechnic, who extolled the medical benefits of Clarksport. Many golf shoes in the past had contributed to the onset of arthritic knees, he said, by not allowing for the twist in a player’s swing. Perhaps letting the occasion get to him, Dr Thomas concluded: ‘This is unique in Britain. You are a British company doing this total deal and putting it in the right place – in a specialised shoe shop, with a total back-up behind it.’

That was the problem. The back-up – in terms of a cohesive strategy supported at the highest level and accompanied by a proper marketing campaign – was in fact never adequately put in place, and bitter wrangles ensued about how best to sell the Clarksport range. Should they be on display in dedicated sports shops? Or should they occupy a corner in Clarks’ traditional outlets, including Peter Lord?

‘The research showed that people wanted to buy sports shoes from traditional shoemakers, but no one really backed the idea at board level,’ says Lance Clark, who was himself on the board:

From the start, there was no real commitment, no desire to invest in it and make it work. Then I made the tactical error of concluding that people would buy them in existing shoe shops rather than sports outlets. The fact is that they did initially, but then they didn’t.

This is a view largely shared by David Heeley, then manager of the Redgate factory in Bridgwater and the man who earlier had entertained Miss World. Over the course of 40 years at Clarks, he worked in almost every division of the company.

‘Clarksport was a real attempt to get into the trainer market, a comprehensive effort,’ says Heeley. He continues:

But the fundamental mistake was that they were sold in our Peter Lord stores and in key independents rather than in sports shops. They just did not sit comfortably beside more traditional shoes. The other issue was that the board wanted to see a return on the investment within two years, which was impossible. Profit was demanded too soon. The sad thing to remember is that we were ahead of Reebok at one time and some of our sailing shoes were worn by the crew of Ted Heath’s Morning Cloud when they were training for the Fastnet race.

Clarksport survived only two years before the range was withdrawn.

‘We just didn’t think it would come to much,’ says William Johnston, a member of the family with broad experience across the company and a specialist in forward planning.

I thought we were already too late to get into trainers and the general feeling at a senior level was that they were part of a phase, like blue jeans. They would go away in time. We thought the same thing about credit cards.

Even forward-planning experts can be caught on the hop, it seems.

Johnston was the son of Priscilla, Bancroft’s sister and therefore Daniel’s first cousin. He joined the firm in 1962 after coming down from Oxford University and then went to Carnegie Mellon Business School in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In 1974, he was elevated to the main board, and as managing director of Clarks Overseas Shoes Ltd, played a leading role in the purchase of the Hanover Shoe Company, after which, in 1978, he was appointed managing director of C. & J. Clark Retail Ltd.

‘The fact is that we were not far-thinking, but you have to remember that some of these things were not blindingly obvious at the time,’ says Johnston. ‘For example, we should have started importing shoes far earlier – we all know that now.’

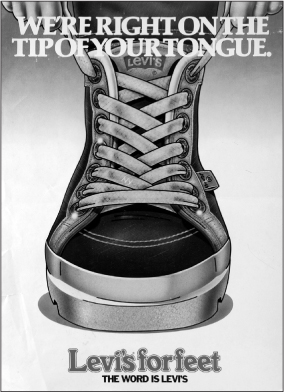

There was still an ongoing appetite for trying new ventures, but perhaps at the expense of addressing issues about the core business. For example, Lance Clark and Malcolm Cotton oversaw the introduction of ‘Levi’s for feet’, a canvas casual shoe imported primarily from Korea. In 1977, after many years of negotiation, Clarks obtained a licence from Levi Strauss and Co., based in San Francisco, to sell these shoes on an exclusive basis in Britain and throughout continental Europe, agreeing to pay a 5 per cent royalty on every pair sold. ‘Levi’s for feet’ had been selling successfully in America since 1975 under licence to the Brown Shoe Company, and expectations were high that the same would happen on the other side of the Atlantic. By January 1978, forecasts for estimated sales in Europe were 900,000 pairs. In addition, it was decided to produce a version of ‘Levi’s for feet’ in the Ilminster, Townsend and Shepton Mallet factories, a variant using leather uppers to distinguish them from the all-canvas model. Names for the ‘Levi’s for feet’ range included Chase, Marathon, Dude and Sneak.

‘This is a lot of extra business for a lot of people, and for the sake of employment the additional business is worthwhile,’ said Lance, speaking at a Clarks Ltd meeting held in the Wessex Hotel, Street, in December 1977.

Lance reported how ‘Levi’s for feet’ had got off to such a ‘flying start that at one stage we ran out of shoes’. Sales in Holland and Germany had been strong, getting off quite literally to a flying start when a light aircraft took to the skies in Eindhoven trailing an advertising banner as it circled the city.

In the UK, there were plans to go nationwide with the range in the spring of 1978. This campaign began with ‘Levi’s for feet’ sponsoring a Southern International speedway event at Wimbledon Stadium in southwest London on 26 April 1978 in celebration of speedway’s 50th anniversary in Britain. There were reports at the time that speedway had become second only to football as a spectator sport, and on the day a crowd of 7,000 headed for Wimbledon, including invited shoe retailers from the Greater London area, who enjoyed a buffet supper in the stadium restaurant before the twenty-race programme began. Barry Briggs MBE, the acclaimed speedway rider from New Zealand who had won the World Individual Championship four times, was on hand to present the prizes, helped by two Penthouse Pets – centrefold models who had been photographed by Penthouse, the magazine widely regarded as a British equivalent to Playboy.

John Aram was general manager of the ‘Levi’s for feet’ division. He told the Courier that ‘what we have got is a long-term agreement between the world’s largest maker of casual clothing, including jeans, and Europe’s largest shoemakers’. He said the range would be aimed primarily at men and children, focusing on the 14 to 24 age group.

Reflecting on the venture, Aram says:

‘Levi’s for feet’ survived for nearly ten years. During that time, there was some disquiet about it, with several members of the board concerned that resources and effort were going into building up the Levi’s brand rather than Clarks, but others thought it was a way of gaining momentum, an opportunity to try something different.

The end for ‘Levi’s for feet’ came in 1987, when the market for trainers and casual shoes suddenly dipped. If you weren’t at the epicentre of the trainer revolution you were in danger of withering at the edges. Clarks asked Levi Strauss if it would reduce the agreed 5 per cent royalty paid on each pair sold to 3 per cent. The US company refused and ‘Levi’s for feet’ was discontinued.

Speedway, Penthouse Pets and aerial promotions may have had an element of gimmickry about them, but they were in keeping with an enlightened outlook when it came to advertising and brand management. In the 1960s, Hobson & Grey, whose clients included Procter & Gamble and General Foods, had taken over from Notley’s as Clarks’ advertising agency. The agency, which became known simply as Grey, found itself liaising with three different executives at Clarks, one representing children’s shoes, another men’s and a third women’s. The board was aware of this cumbersome chain of command, but it also felt that Grey’s was too old-fashioned, and so decided to invite other agencies to tender for the Clarks account, a process from which Collett Dickenson Pearce (CDP) emerged triumphant in September 1974.

‘Levi’s for feet’ were sold by Clarks in Britain and Europe under exclusive licence from Levi Strauss from 1978 to 1987.

Robert Wallace, Clarks marketing director, who had joined in 1971 from Benton & Bowles, the advertising agency, said in an interview in 2006 that Clarks had been looking for an ‘agency [that] would if necessary get tough with the client … large firms [like Clarks] sometimes need tough handling. We did not want an agency that might reflect our own opinions back to us’.

Collett Dickenson Pearce was a breeding ground for talent. Among those who cut their creative teeth at the agency were Charles Saatchi, David Putnam, Ridley Scott and Hugh Hudson. CDP was regarded as sharp and known for its clever slogans, such as ‘Happiness is a cigar called Hamlet’ and ‘Heineken refreshes the parts other beers cannot reach’. Suffice it to say that the worlds of Collett Dickenson Pearce and Clarks were markedly different.

‘Collett Dickenson Pearce arrived for their first meeting … One was in a Porsche 911, one was in a Maserati Bora and one was in a Ferrari,’ says Philip Thomas, Clarks advertising manager at the time.

They came in and they looked the part as advertising people. They wanted to make a statement in this sleepy little town, that we’re here to help you as a business and we know what we’re doing. They strutted their stuff but also delivered. That was a key mind-set change for us. We’d gone from the Grey days to Collett Dickenson Pearce.

Thomas says that Grey’s was in the habit of coming up with four or five creative concepts and ‘you’d be sitting there [thinking] which one do you like, not which one is right. But with Collett Dickenson Pearce they’d come down and present one concept and usually it was bloody good.’

One of its first press campaigns featured Long John Silver, accompanied by the line ‘There’s Only One Clarks’. A television and cinema advertisement showed children running on a beach as if in Chariots of Fire, to the accompaniment of music similar to that in the film. This ended up being the subject of legal wrangling which eventually led to action in the High Court, where Mr Justice Vinelott banned the ad in April 1983, ruling that it was ‘blatant plagiarism’. On other occasions, some of the advertising became overtly raunchy, such as when, in an ad that showed how Clarks had changed over the years from making strait-laced court shoes to six-inch stilettos, models were seen wearing calf-length négligées for the former, nothing very much at all for the latter.

One press advertisement had eight women standing in a row. The woman on the far left was wearing a knee-length skirt and conservative shoes, the woman on the far right showed a naked leg and wispy party shoes. ‘We deserve to be on every woman’s black list’ read the caption, referring to a woman’s guilty pleasures or secret desires.

Another featured four attractive young women in leather boots astride a horse. ‘Black beauty. Also brown beauty, tan beauty and black-and-tan beauty’ read the copy. And just in case consumers still felt Clarks was rooted in a previous century, CDP came up with an advertisement featuring a group of models in silk petticoats and camiknickers kicking their legs in the air as they danced the can-can. ‘Nobody can accuse us of being narrow-minded,’ the copy said.

Maybe not, but some thought the pendulum had swung too far the other way. ‘Mr Millward, who had twenty or so shops in the South of England, summoned Lance [Clark],’ Robert Wallace recalled many years later.

So Lance said, ‘This is it, you’d better come and explain yourself,’ so we went to Reading and Lance took out a sketch pad and there was a church outside the window of the meeting room. I got absolutely pilloried by these very religious Millwards people … that it was disgusting and disgraceful and so on. It would encourage pornography and goodness knows what. Lance said not one word and I had to defend it and at the very end they said: ‘Well, Mr Clark, thanks for the meeting, what’s your view?’ And he said: ‘There’s my view,’ and handed over this sketch he’d done of the church. Then we left.

![]()

Clarks also placed a growing emphasis on graphic design, engaging in the mid-1970s the services of Pentagram, one of the country’s most successful design consultancies, to revamp all its shoe boxes, look at its permanent displays in Peter Lord shops and in other outlets selling Clarks, and generally coordinate all point-of-sale communication with consumers.

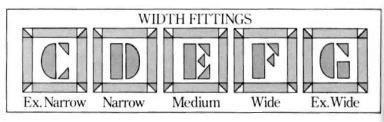

The distinctive lettering designed by Pentagram in the 1970s for the width fittings on Clarks shoe boxes.

‘We had to improve the whole presentation of the brand, but it wasn’t easy,’ says John McConnell, who was a partner and director of Pentagram.

Some of those independents were dowdy places that smelled of boiled cabbage. They used to have hardboard signs on the walls and all the stock was hidden behind a curtain or stored downstairs. One of the first things we did was redesign the boxes and then we tried to persuade the shops to have the boxes on display – rather than having a shop assistant go downstairs and return ten minutes later to say she didn’t have what you wanted.

A new design policy for children’s shoes was a high priority. Any scheme had to look modern but at the same time provide tangible links to the traditional consumer perception of Clarks. Pentagram opted for simple decorative geometric shapes in bright colours, similar to children’s coloured blocks. The Clarks logo became thicker and was shown in bright yellow on a green background. In Living by Design, published in 1978, the Pentagram partners wrote:

The need to support the product in the retail outlets required the design of hardware, including shoe display units, footstools, mirrors, a tie-your-own-shoelaces device, in fact almost everything except the boundary of the space.

The Clarks green boxes were smart and authoritative, with the code, style, size and width of the shoes clearly displayed at one end, making it easy for both the shop assistant and the consumer to identify what he or she was looking for. The typeface for the width fitting was chunky, the letters enclosed in a thick square. C represented extra narrow; D was narrow; E was medium; F was wide; and G was extra wide. According to Pentagram:

The intention is that the shoe boxes will have the additional purpose of creating a brightly coloured wall in the shop, not only promoting the shoes but also enlivening what was previously one of the least attractive aspects of most shoe shops or departments.

Clarks understood that children did not consider shoe shopping the most exciting outing of the school holidays, and so part of Pentagram’s brief was to find novel ways of keeping youngsters amused while they had their feet measured and were fussed over by a shop assistant. This led to the introduction in the late 1970s of colourful display panels, moulded in styrene and displayed in bevelled, enamelled frames. Many of these were illustrated by Graham Percy, a New Zealand-born artist who had won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in the 1960s. He produced a series of pictorial puzzles that quietly promoted shoes while aiming to capture children’s attention. One comprised a collage of cartoon characters in which ten pairs of shoes were hidden in the background. ‘Can you find them?’ read the caption. Another encouraged children to match up footprints to a group of animals walking in desert sands.

Reflecting on those days of branding and advertising, Robert Wallace says his biggest challenge was to make the three divisions of Clarks – children’s, men’s and women’s – ‘look as if they actually belonged to the same company’ and that he had to work hard to persuade each division head (whom he called the ‘barons’) to support the advertisements. He recalls:

At one point, I realised that our ads were much more fashionable than our shoes ever were, but that was the idea. Lance was determined to bring the company up to date and I was there to help him. We had to set up a clear strategy for the brand and would not deviate from it. Simply put, children’s was all about a true fit; men’s was about hightech comfort and durability, and women’s was to do with comfort and style – but mainly comfort.

Collett Dickenson Pearce’s director on the Clarks account was Geoff Howard-Spink, who went on to become one of the advertising world’s elder statesmen. ‘The advertising, when it appeared, was unlike any shoe advertising that Clarks, or the shoe industry, had seen before,’ said Howard-Spink, writing for Inside Collett Dickenson Pearce, an illustrated book about the agency published in 2000. ‘The quotes for photographs were staggering. For the price of each press ad you could have shot a television commercial. It was very difficult to explain these prices to Clarks, a Quaker family with a shoe business.’

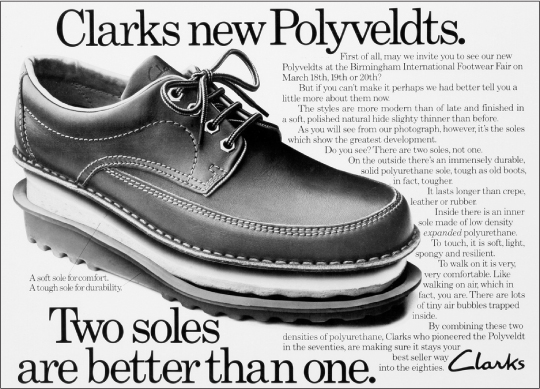

In 1979, a CDP advertisement for Clarks’ ‘Cornish pasty’ shoe – so named because of its thick, gently curved edges that reminded people of the popular crusty pie – was shortlisted for an advertising award. These shoes had Polyveldt soling and the copy in the advertisement explained how Polyveldt, known in the trade as PV or PU, was made of Contura, a polyurethane exclusive to Clarks.

Apart from durability, Contura gives the Polyveldt sole its flexibility and lightness (Contura is actually half the weight of leather or crepe) … we hope you’re an ordinary man in the street and, having read this far, will rush out in search of a pair of Polyveldt of your own.

Then came the waspish line:

Should you, however, be a rival shoemaker, we’d like to draw your attention to the fact that British and foreign patents and designs are pending or granted. And that Polyveldt are protected by UK Reg Design Nos 967050 and 967051 and Irish Reg Design Nos D3665 and D3664.

Clarks remained with CDP until 1981, when Geoff Howard-Spink and his business partner, Frank Lowe, left to form their own company, Lowe Howard-Spink.

Clarks new Polyveldts – successors to the so-called ‘Cornish pasty’ shoe.

Developing the Clarks brand was not just down to advertising and graphic design. In the late 1960s, the company hired a market and social research company called Conrad Jameson Associates to advise on Clarks’ image and its positioning among consumers. Conrad Jameson was an American living in London who had studied philosophy at Harvard. One of his junior staff was Peter Wallis, who, using the name Peter York, went on to co-author the bestselling Official Sloane Ranger Handbook in 1982. When Wallis left to found his own company, the Specialist Research Unit Ltd, with Henry ‘Dennis’ Stevenson (now Lord Stevenson) in 1973, he reached an amicable arrangement with Jameson, whereby the Specialist Research Unit took on the Clarks account.

Wallis spent the next twenty years advising Clarks, sometimes intensely, sometimes more loosely. He worked closely with Lance Clark, Robert Wallace and Michael Fiennes, a cousin of Sir Ranulph Fiennes, the adventurer and writer.

Michael Fiennes had joined Clarks as a graduate trainee in 1963 and was universally credited with having a first-class brain. One member of the Clark family says he was ‘probably too bright for us’. After graduating from Oxford University with a degree in philosophy, politics and economics, and with the encouragement of Tom Woods, Clarks personnel manager, Fiennes secured a place at Harvard Business School. On his return in 1968, he was fast-tracked into management, working in marketing and then moving to Australia as marketing director in 1971. He returned to Street in 1973 as head of marketing and strategy and became corporate marketing manager of Clarks Ltd, with a seat on the board. However, he was never promoted to the main C. & J. Clark board. He remained with the company until 1982, when, without any warning, he suddenly resigned. ‘It was a great shock’ says David Heeley:

He had the brain-power to help steer the company through difficult times, but it must have seemed to him that there was little chance of getting on to the main board because it was top-heavy either with family members or long-term retainers, who had done a great job but perhaps were no longer at the top of their game.

The loss to Clarks was highlighted when, within a few months of his departure, Fiennes set up his own company and won the exclusive UK rights to sell and distribute Ecco shoes, a leading boutique brand from Denmark. This deal lasted seventeen years and was extremely successful, only coming to an end when Ecco launched its own international sales force. In the early 1990s, Fiennes opened Ecco’s first shops in Kingston and Bromley and by 1999 there were fifteen such outlets. He and his wife Rosalie, an architectural interior designer, went on to set up the retail shoe and clothes company Shoon.

‘Making shoes was part of Clarks heritage and it was difficult for some members of the board to contemplate anything else,’ says Fiennes. He continues:

But even if we had thought about bringing in shoes from overseas and concentrating more on wholesaling than manufacturing we were not prepared for it. It was never clear where the company was going long-term and members of the family were pulling in different directions. Even so, I never found another company that I preferred to work for. Clarks was not afraid of looking at new things and always wanted to be at the forefront of change. I used to see Daniel for strategic discussions and I liked him enormously. He was bright and wanted to do the right thing but he didn’t have the authority of his father [Bancroft] over other members of the family.

Wallis’s experience was similar:

My role was to present the outside world as a sounding point. We did a lot of research that always confirmed the same thing: either Clarks should stick to its core business or, if it wanted to become a fashion item, then it had to do it very well. I argued that you have to find your sweet spot and stick with it. The frustration for me was wanting them to act faster and to understand design better. A great deal of the design came from barmy enthusiasm rather than inspired imagination.

Pride was felt keenly at Clarks over its technological advances. As one former senior manager puts it: ‘The genius of the company was that it came across as middle of the road when in fact it was at the sharp end of shoe production and never afraid of new techniques, new innovations.’

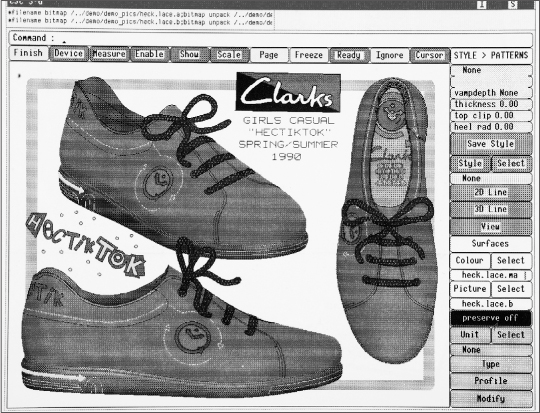

The use of computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM), developed by Tony Darvill in Street, was a case in point. It offered for the first time the ability to design a shoe from start to finish on screen via an integrated three-dimensional (3D) and two-dimensional (2D) computer software package. The dimensions of a last were digitised and the software allowed the designer to examine and alter the cut of the shoe, its decoration, heel and sole edge, and to see his work from each side, from above or from the back. The designer could also experiment with different colours or colour combinations, effectively doing away with the old trial-and-error method whereby experimental shoes were made from scratch.

CAD (computer-aided design), as seen in this design from 1990, was developed in Street and widely used throughout the Clarks business from the late 1970s onwards.

Darvill was working in Clarks’ research and development department when he first started developing his ideas in the 1960s, long before the invention of desktop computers. 3D modelling was the subject of in-depth research at Cambridge University’s computing laboratory in 1965 and, towards the end of the 1960s, Citroën, the French car manufacturer, made strides in computing complex 3D curve geometry. Darvill was known as a genial eccentric with a forensic eye for detail, who had knowledge of aircraft and car manufacturing and applied his engineering skills to shoemaking. His fascination with footwear sprang in part from wanting to know what kept a straightforward court shoe securely on a woman’s foot.

‘In my mind, the court shoe is the optimum shoe design,’ said Darvill in an interview in 1995. ‘It has no laces or straps, it only covers a small part of the foot and yet it fits comfortably and remains on the foot during walking.’

Darvill set about perfecting the design process, providing a capability to flatten the last in a consistent and repeatable manner. This allowed for communication between designers, pattern engineers, component suppliers and production managers, even if they were based in different parts of the world. They were sharing exactly the same information.

‘Shoemaster’, as Darvill’s product was called, was given a boost in 1977 when Clarks collaborated with the Computer Aided Design Centre (CADC) in Cambridge and made a presentation to the Clarks board. Not long afterwards, CAD/CAM teams were assigned to a number of Clarks factories and the software was eventually sold to other shoe manufacturers in the early 1990s.

One of the first companies to show an interest in the product, after seeing it at a trade fair in Germany, was Torielli, an Italian firm southwest of Milan that specialised in shoemaking equipment and had direct contact with shoe manufacturers across the world. Clarks and Torielli joined forces on the Shoemaster project in a 50–50 joint venture, and then in 1996 Shoemaster became independent of Clarks and formed a new company with Torielli called CSM3D. The final Clarks shares in CSM3D were sold to the new management team in 2003 and CSM3D now owns the intellectual property rights. Its UK headquarters is still in Street, and Ian Paris, the chief executive, is a former Clarks employee. CSM3D produces four new versions of its software a year and sells to companies such as Bata, Gucci, Chanel and Bally. Relations between CSM3D and Clarks remain close and Darvill would be a contender to occupy a plinth in Street if the opportunity were to arise.

No one could accuse Clarks of not trying to diversify. Indeed, some would say it tried too hard. The launch of a children’s range of clothes in 1979 was a leap too far. Clarks had begun thinking about embarking on this operation in March 1977, with Wallis’s Specialist Research Unit producing a favourable report on it six months later. In December of that year, the board agreed that there was an opportunity to sell ‘well-designed products … to those mothers who want something different from chain store offerings but at a price below specialised suppliers’. According to the planning department in Street, the aim was to secure 1 per cent of the total market share, which, it was estimated, would generate £4.5 million a year at 1976 trade prices. A children’s clothing manufacturer, Pasolds, would be ‘approached to assist in development and manufacture’.

Malcolm Cotton held a series of senior managerial roles at Clarks from the 1960s onwards, and was briefly managing director of the company in 1995.

The results were sobering. It made losses of more than £300,000 in its first year of trading in 1979, and a loss in excess of £350,000 in 1980, before being withdrawn in 1981. Norman Record, Clarks group economist, sought to explain the failure of what was called the ‘Children’s Clothing Project’ in a document written for Daniel Clark. He said it was

… clearly not well managed … the combination of entrepreneurial qualities necessary for success in new projects of this kind is likely to be very rare in a largish organisation like ours. Our ability to launch such projects must thus be recognised as extremely limited.

Record went on to say that if Clarks is to ‘succeed in a large market we must devote appropriate resources and set our sights sufficiently high. Half-hearted attempts are bound to fail.’

This set-back followed the closure in September 1978 of Silflex, one of Clarks’ original factories in Street. To the outside world, this was an inevitable development, softened by the announcement that most of the 230 workers would be relocated to other factories in the West Country – but for Clarks it was an emotional wrench that was hard to bear because it struck at the heart of the company’s manufacturing history. The original Big Room, where shoes had been made since the turn of the century, had been silenced.

Most people, even members of the National Union of Footwear, Leather and Allied Trades (NUFLAT), had realised for some years that the sums did not add up. At one time in the early 1960s, some 22,000 pairs of women’s shoes were being made each week in Street. By 1978, that number was down to 7,000 pairs. Even so, the closure came as a shock to employees who gathered in the Strode Theatre on a Tuesday afternoon that September to be told the news by Malcolm Cotton, then divisional general manager for women’s shoes.

The Courier reported Cotton as saying:

This has happened because over the years the needs of our customers have changed, and despite every effort to move with the times, we have not been successful in finding the right products.

At one point in the meeting, a long-term employee confronted Cotton. ‘If it wasn’t for my father and grandfather you wouldn’t have a job today,’ he said. Cotton replied:

I do not accept that I sit here today owing my job to anyone’s father or grandfather, because if I was not doing this job then I would be doing something else … I simply believe there is a job to be done, however unpleasant, to try and get the best results for the company and its employees in the long term. We must work for the present, plan for the future and not contemplate the past.

Cotton was not a family member, but he rose to become managing director of C. & J. Clark Ltd in the 1990s. He joined the company in 1965 from Procter & Gamble as an internal consultant and within six months was put in charge of the Silflex factory. In the early 1970s he worked in Ireland, before returning to Street, first as head of the men’s division, then of the women’s division.

Reflecting on the Silflex closure, Cotton describes it as a ‘seminal moment’, while Lance Clark, who was managing director of Clarks Ltd at the time, says it was a ‘horrible thing to do’ that went completely against the Clarks belief in secure employment. But, says Lance:

… it was the right thing to do, and looking back we should have closed more factories much faster … We should have been hard-headed about it. One of the reasons we dragged our feet was because it would cost us £1 million every time we closed a factory. In the accounts the costs of closing factories came out of trading profits so there was a positive disincentive to take the necessary painful decisions.

A combination of rising raw materials, a flattening national economy and changing fashion trends that Clarks was struggling to keep up with began to take its toll. On 22 August 1980, the company announced the closure of Trefano, the factory in Wales, and its satellite unit, White Rose, with the immediate loss of 390 jobs. In addition, there were redundancies at the Dundalk factory, in Ireland, and at the Vennland factory in Mine-head. Only a month earlier, there had been job losses in Street, Yeovil and Weston-super-Mare, so that by the end of 1980, the total workforce in Clarks UK factories had fallen by nearly a ninth from 8,500 to 7,700.

Daniel Clark was running the company at a dispiriting time for UK businesses. In 1979, when Margaret Thatcher came to power, inflation was in double figures and unemployment was at a post-war high of 700,000. Government debt required borrowing from the IMF.

Internally, it wasn’t easy either. The larger a family business becomes the more complex it is to run, the more onerous to resolve differences among shareholders. The Institute for Family Business says that only 13 per cent of family businesses survive to the third generation, but by the late 1970s Clarks was a fifth-generation family, albeit burdened by many of the inherent disadvantages that come with such a long history. It was only in the 1990s that Clarks started to make the transition from being an owner-managed company to being family-owned but employing professional managers to run the business. The obstacles facing Daniel were immense in comparison to those of, for example, his great-grandfather, William S. Clark, who was the overwhelming majority shareholder with the freedom and authority to make decisions as he saw fit.

Daniel did not attempt to disguise the challenges. When pre-tax profits in 1980 fell to £8.7 million, some 30 per cent below those of 1979, he described them as ‘very disappointing’. The Courier also was straight to the point: ‘The best thing that can be said about 1980 is that it is over.’

![]()

Relations with K Shoes – which had been founded in 1842 by Robert Miller Somervell – had always been close, and would become even closer by the end of 1980. Without warning, but operating within the guidelines on mergers and take-overs, Ward White, manufacturers of Tuf, Gluv, John White, Portland and several other lower-priced footwear brands, launched a hostile ‘dawn raid’ for K Shoes on 21 October 1980, acquiring a 14.85 per cent stake. Ward White paid 60 pence a share, when K Shoes shares had been trading at 47 pence. Clearly, a full bid was in the offing. Ward White was slightly bigger than K Shoes, with a market capitalisation of around £16 million compared with K Shoes’ £14 million. It had 100 shops, trading as Wyles, and had recently bought twenty retail outlets in Sweden and 50 in North America.

On the afternoon of 21 October 1980, the K Shoes chairman, Spencer Crookenden, and his managing director, George Probert, met their counterparts at Ward White, who were George McWatters and Philip Birch. McWatters and Birch spoke, Crookenden and Probert listened. The news went down badly in Street. K Shoes was a big brand and the Clarks board did not want it to fall into the hands of competitors. The next day, Daniel Clark telephoned Crookenden to say that Clarks felt compelled to make a counter bid. On 23 October 1980, a meeting was convened at the London offices of Schroders merchant bank, attended by Daniel, Lance and William Johnston, from Clarks, and by Crookenden and Probert from K Shoes. Crookenden stressed how he wished K to remain independent, but if this proved impossible he would rather be in business with Clarks than Ward White, provided K Shoes could maintain its own identity.

‘We were much impressed by the character of the Clarks directors, and we particularly admired the quality and total trustworthiness of the chairman, Daniel Clark,’ wrote Crookenden in his book K Shoes: The First 150 Years, 1842–1992.

The next day, Crookenden issued a statement to all K Shoes’ employees, explaining the firm’s position and ending with a plea that ‘we should all continue to work normally’. Evidently, the one person not working normally was Crookenden. First, he had to appoint a new merchant bank because Clarks and K Shoes shared the services of Schroders. Clarks had been with Schroders the longest, and so it was left to K Shoes to make a new appointment. It was agreed that Kleinwort Benson would take on this role, with Lord Rockley as the senior adviser. Further negotiations ensued with Ward White, after which K Shoes promised to make a definite decision within seven days. That decision was taken on 4 November 1980 in favour of the Clarks bid. As Crookenden explains:

The K Shoes board decided that Ward White were not the right partners for us … we gained the feeling that they did not understand the real strengths of K Shoes, and we saw no chance that the two companies would work together in harmony.

But he saw every chance that K Shoes could work with Clarks. On 30 October 1980, Clarks offered 68 pence per K Shoes share, significantly less than the £1 a share K Shoes was looking for. ‘George Probert left the meeting in disgust, feeling that they were not really serious in making an offer,’ according to Crookenden. There was also concern that the Monopolies and Mergers Commission (MMC) could scupper any deal, given that Clarks already had around 9 per cent of the total UK shoe market, and K Shoes had 3.5 per cent.

Ward White re-entered the chase after K Shoes published its year-end results on 26 November 1980, showing pre-tax profits of £5.5 million, an increase of 10 per cent on the previous year. The K Shoes share price rose to 78 pence on the back of its results. Ward White submitted a draft of its take-over proposal to K Shoes on 2 December 1980. Meanwhile, K Shoes sent its own terms to Clarks, and on 9 December Daniel telephoned Crookenden to confirm an offer of 95 pence per share, a cash bid of £22.4 million. The deal was done, subject to confirmation from the Office of Fair Trading, which duly came shortly after Christmas, that the bid would not be referred to the MMC.

Crookenden and Probert immediately joined the main C. & J. Clark board, with the former expected to retire in 1983. It was agreed that the K Shoes shops would not have to stock Clarks shoes nor Peter Lord shops be required to sell K branded shoes. Additionally, K Shoes would continue to have its own sales force, its own advertising and marketing department and would negotiate its own terms with the unions. Clarks issued a statement saying that it did not ‘foresee any redundancies or job losses, salary or wage reductions’ for K Shoes employees.

There are two ways of looking at the purchase of K Shoes. The first is that the two firms were a perfect fit, sharing a shoemaking heritage and a commitment to a wider social responsibility. Clarks had 550 shops and K Shoes had 220. Clarks had 20,000 employees worldwide, K Shoes had 5,700. Clarks produced 15 million pairs of shoes a year, K Shoes made 5 million, and so joining forces made commercial sense. Together, Clarks and K Shoes would provide stiff competition for other UK-based manufacturers and shoe retailers. Both companies would gain from fresh input from their respective senior management executives. Neither brand would be diluted and both companies would continue to negotiate separately with their customers about discounts and other promotions.

As Daniel put it to shareholders:

The Clarks board in 1981 shortly after the acquisition of K Shoes. George Probert, previously K Shoes managing director, is standing at the far left. Others in the back row (left to right) are Jan Clark, Eric Gross, Anthony Clothier, John Frith and Lance Clark. Front row: William Johnston, Spencer Crookenden (previously K Shoes chairman), Daniel Clark and Ralph Clark. George Probert was later managing director of Clarks, from 1985 to 1987, when he made extensive changes to the board.

We now have the major share of the manufacturer branded business in the UK, distributing national promoted brands through our own shops and some 3,000 or so other outlets. We believe that for the future this is the one significant way of competing in the market place with the major national retail multiples.

And indeed there were years when K Shoes made a significant contribution to the profits of the company.

But an alternative view – and one that has gained weight with the benefit of hindsight – was that Clarks had bought a company with very similar problems to its own. Rather than helping the firm to move forward, the acquisition of K Shoes would root it to the past. Indeed, when it came to matters such as sourcing from overseas, marketing and distribution, Clarks was, if anything, ahead of K Shoes. Paying £22 million – money borrowed from the bank and due to be repaid in 1987 – simply to compound your difficulties was a risk.

And so it would prove. Arguably, K Shoes should have followed the Clarks lead and begun closing some of its less profitable factories. Instead, it pushed ahead with the new Millbeck plant in Kendal, which was built by the Eden Construction Company at a cost of £820,000 with a completion date set for June 1982.

‘In spite of the overall trading situation, Daniel Clark urged the K Shoes directors not to be too pessimistic about the economic outlook and to continue to invest in order to improve productivity and to expand retailing,’ wrote Crookenden.

K Shoes results for 1981 were worrying, but were even worse in 1982, when profits fell from £4.2 million to £2.8 million. A new lightweight walking boot designed in close cooperation with Chris Brasher, the Olympic gold medallist, failed to raise spirits in Kendal, and even a range trading under the name of top fashion designer Mary Quant was withdrawn after less than two years.

In the annual report for the whole group, Daniel confirmed that all chains within C. & J. Clark Retail Ltd had ‘failed to meet budgeted sales, in some cases, by a considerable margin’. Furthermore, there had been losses in North America – ‘partly by expanding too rapidly’ – and in Europe, while Avalon Industries had experienced a ‘bad year’. It was also the case that during the recession consumers were ‘buying down’, unlike in the past when they had tended to stick with brands they trusted.

While telling the K Shoes directors not to be downcast, Daniel seemed a little disheartened himself, saying that prospects in the UK ‘do not look very encouraging’ and that trading conditions were so unpredictable that ‘I am reluctant … to forecast what the outcome will be.’

The outcome for the first six months of 1982 was a disaster. Net profit before tax for the first six months in 1981 was £10.7 million, falling to a loss of £1.2 million twelve months later.

But there were some happy diversions in the early 1980s. The wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer in the summer of 1981 led to a run on traditional, low-heeled court shoes as worn by the young princess. Clarks capitalised on this by introducing its ‘Princess Di’ shoe, formally known as the Quiver, which retailed at £14.99. Starting with this one model, Quiver soon became a whole range of footwear. Developed in the Barnstaple factory, Quiver shoes were then produced in bulk in Plymouth, Barnstaple, Exmouth and Shepton Mallet, as well as in Dundalk, where 60 extra staff were taken on to cope with demand.

Meanwhile, the Queen had dropped in to the Peter Lord shop in Staines in March 1980 when she opened the new Elmsleigh shopping precinct. Three years later, the Duke of Edinburgh, in his role as president of the Royal Society of Arts, presented Clarks with the Award for Design Management, an accolade to mark the contribution design makes to the commercial success of an organisation. And just in case Clarks’ younger customers were in danger of losing interest, Noel Edmonds, then a leading radio DJ, attended a children’s division sales conference to endorse Clarks teenage ranges.

But nothing could disguise the anxiety over the company’s overall performance, and there was no attempt to do so in the pages of the Courier. In the spring of 1982, the following exchange was printed when Lance Clark was grilled by the company’s public relations manager, Ian Ritchie.

‘So why have sales been worse than expected?’ asked Ritchie.

‘The main factor is price,’ said Lance. ‘In the bad economic times people are paying less for their shoes. We’ve got to get the price of our footwear down.’

‘I think you’re blaming outside influences a great deal,’ said Ritchie. ‘You blamed the imports and you’ve blamed the consumer for buying the lower price shoes, but surely some of the criticism must be directed inwardly at the management of the business?’

‘Yes, I must accept, as managing director, that it is my total responsibility. We have made mistakes. Looking back, had we forecast more accurately the severity and depth of this depression, yes, I should, knowing what I now know, have taken much tougher action more quickly and more aggressively than we did.’

Within months of giving that interview, Lance was replaced as managing director of Clarks Ltd – which was responsible for all UK manufacturing, wholesaling marketing, advertising, personnel and planning – by 43-year-old Malcolm Cotton. Lance, a major shareholder, faced the prospect of being sidelined when he was given the role of developing C. & J. Clark Continental Ltd. The Courier thundered once more, this time with a whiff of mischief, quoting Petronius, a Roman satirist, who in AD 66 observed:

No sooner did we form into teams than we were reorganised. We tend to meet every new situation by reorganisation, and what a wonderful method it is for giving the illusion of progress whilst only producing confusion, inefficiency and demoralisation.