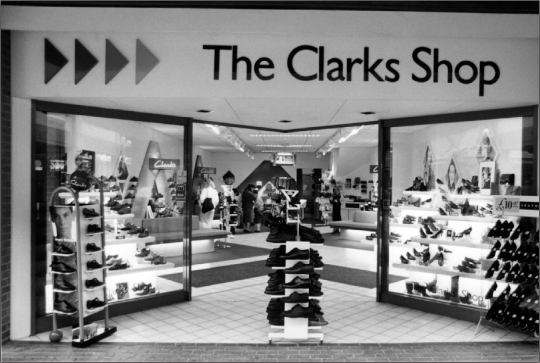

Until 1984, Clarks shoes were sold through a wide-ranging network of shops trading under many different names. In that year four shops were opened under the name of ‘The Clarks Shop’ for the first time.

THE GULF between manufacturing and retailing at Clarks seemed impossible to bridge. Manufacturing wanted – and was encouraged – to protect its margins, while retailing wanted – and was encouraged – to buy in shoes at the cheapest possible price. Divisions between the two arms were historic. Manufacturing represented the past: retail was positioning itself as the future – but without the retail experience at managerial level to embrace that future. There were even lifestyle differences. Retailers tended to smoke, manufacturers didn’t. As one member of the Clark family recalls:

Retailers and property people made up the hard core of smokers. They tended to be at the happy-go-lucky, can-do, cup-always-more-than-half-full end of the spectrum. Originally, smokers and non-smokers all mixed together in Street. Then the Human Resources lot got busy and closed the separate senior staff canteen so that all grades shared the same canteen space. However, the canteen was divided into smoking and non-smoking sections, forcing the two cultures apart.

But smoking was the least of the worries. The big question was how Clarks could continue as a profitable manufacturing and wholesaling company. The answer that dared not speak its name was that it couldn’t. This was to consume the minds of senior managers throughout the 1980s and almost consumed the company in the process.

Costs were too high to sustain the factory system and nothing could be done to stem the tide of cheap shoes coming into the country. Daniel Clark said in his annual report for the year ending 30 January 1982 that imports accounted for over half the total number of shoes sold in the UK. And in its 1981 ‘Strategy for C & J Clark Ltd: Final Report’, the Boston Consulting Group had painted a similarly gloomy picture, continually using the word ‘disadvantage’ when considering the company’s position as a UK-based manufacturer. ‘Unless Clarks can offer merchandise which is competitive with imports, erosion of its market share may be inevitable,’ it said, echoing a refrain in previous consultation documents.

Later in that report, it said: ‘Clarks [should] consider importing parts of its product offering. Failure to do so is likely to lead to a gradual erosion of Clarks market share.’ In its concluding recommendations, the group called for a halt on manufacturing certain women’s lines, including: ‘premium fashion courts and dress sandals’; women’s ‘sporty courts and moccasins’; women’s ‘warm-lined and fashion boots’; part of women’s ‘premium and medium price sandals’; and all ‘women’s slippers’; as well as some ‘men’s medium price casuals and sandals’ and all ‘children’s warm-lined boots’.

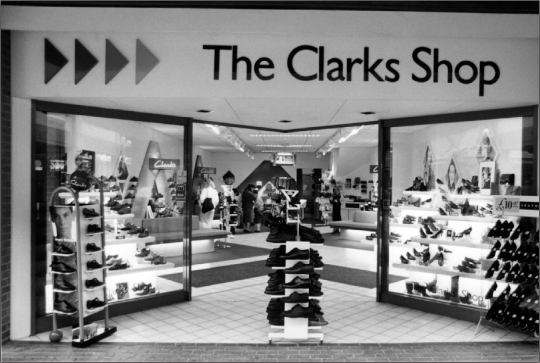

On the high street, meanwhile, the retailing arm of Clarks formed a complicated web of shops that fell under different command structures, encompassing disparate retail names. But Clarks was not one of those names – at least not until 1984. In total, C. & J. Clark Ltd operated some 900 outlets at the start of that year, trading under Peter Lord, K Shoes, Bayne & Duckett, Ravel, John Farmer and James Baker. Flotilla Shoes Ltd was a subsidiary set up to oversee the management and day-to-day operations of the smaller chains such as James Baker, which Clarks bought in 1977, and Bayne & Duckett, both of which operated in provincial towns in Scotland, Wales, the Midlands and north London. There were 290 Peter Lord shops, mainly in prime, rented city-centre sites, stocking Clarks, K and other higher-end brands. Ravel sold no Clarks or K at all, focusing almost exclusively on imported fashion shoes for the teenage and early-twenties market. Ravel shops tended to be close to major fashion retailers.

Three years earlier, the Boston Consulting Group had been scathing about Ravel, describing its performance as ‘volatile’ and ‘sub standard’ compared with competitors such as Dolcis, which habitually achieved 60 per cent more sales per shop and had some three times more outlets. ‘Ravel presently enjoys little synergy with other CJC [C. & J. Clark] operations’, Boston Consulting Group said.

John Farmer was bought in the spring of 1984. It was previously owned by Hanson Trust, which once controlled John Collier, Richard Shoes and Timpson, and had nearly 100 shops in the south of England, pitched at the middle market and selling a wide range of both Clarks and K. In addition, Clarks footwear was available in more than 2,000 independent shoe shops – and the independents accounted for 25 per cent of the UK market. Close ties were maintained with the independents and there were still perpetual fears about the consequences of jeopardising such long-standing links.

David Lockyer was the first-ever graduate trainee to be assigned to the retailing side of the company. Even since retiring from Clarks in 1996 he has continued to keep an eye on the shoe business, recently as a non-executive director of Barratts, the footwear firm based near Bradford, West Yorkshire, which went into administration in December 2011. He joined Clarks in 1968, after which he became a Peter Lord branch manager, then an area manager and finally general manager of Peter Lord before moving into resourcing in the mid-1980s.

When I started, Clarks was a manufacturer and wholesaler, with a small retail sector, amounting to around ten per cent of the whole business. Those of us in retail always thought we should be pushing for the Clarks name to be above the shop door, but we weren’t sure that the ladies’ brand was strong enough, and it was only when we started resourcing from places like Brazil and Italy and one or two other countries that it became a viable option. Many of us had grown up in the business and we were perhaps too engrained in the idea that we were a manufacturing company and, let’s face it, we were good at what we did. I suspect that we needed someone to come along from outside to shake things up a little.

Retailing was expensive, involving the signing of 20- to 25-year ‘institutional leases’, with five-year upward-only rent reviews of the kind that pension funds involved in commercial property would find acceptable. At the same time, something needed to be done to challenge the British Shoe Corporation, which was still the biggest shoe retailer in the country. Its brands included: Saxone; Curtess; Lilley & Skinner, Freeman, Hardy & Willis; Dolcis; Trueform; and Manfield. Of those, Dolcis was the most fashionable and expensive, while Freeman, Hardy & Willis was regarded as downmarket from Clarks. Manfield, with its base in Northampton, occupied a middle market position not dissimilar to Clarks.

John Clothier, the son of Peter Clothier, was in charge of the retail side of Clarks’ business. He had joined the company in 1969 after spending two years at Humanic, a retail-led shoe business in Austria, with which Clarks had close ties. Reflecting on the some of the issues from the early 1980s, he says it was ‘quite clear’ that the British Shoe Corporation dominated the High Street and it was ‘just as clear’ that Clarks needed to strengthen its retail position if it were to compete effectively. He continues:

The costs of retailing were rising fast and we needed to prove that Clarks over the door would work. Then it was a case of completely reorganising our retail portfolio.

Among those pushing for the launch of Clarks ‘over the door’ and who hoped to see many existing Clarks-owned outlets coming under the one banner, was Robert Wallace, the company’s marketing director. He lobbied Howard Cook, Clothier’s right-hand retail man and a driving force behind the launch of the first Clarks shops – and finally, in the summer of 1984, four shops opened in quick succession of each other. Called ‘The Clarks Shop’ rather than Clarks, as they are today, they were regarded as ‘concept’ outlets that dealt almost exclusively in branded Clarks and K shoes, plus a small proportion of ‘Levi’s for feet’. The first of these units opened several miles away from London’s West End in unfashionable Tooting. This was followed by a second shop in Knowle, just outside Bristol, in a store once owned by A. J. Bull, an independent selling mainly Clarks, and a third in Beaumont Leys, a new shopping centre on the outskirts of Leicester. A fourth shop was unveiled at the end of June in Welwyn Garden City, with a staff of four, two called Julie and two called Jane.

Until 1984, Clarks shoes were sold through a wide-ranging network of shops trading under many different names. In that year four shops were opened under the name of ‘The Clarks Shop’ for the first time.

Within twelve months, The Clarks Shop branding had been replaced by just Clarks, and there were eighteen such outlets, located in areas poorly served by traditional retailers stocking Clarks, especially in the inner cities. Brightness and space was what they had in common, with an emphasis on the shop windows displaying as full a range as possible. The consensus was that these shops immediately benefited from not having to feature conflicting brand display cards, but it was also the case that some of the gaps in the Clarks range were exposed. There was a particular under-representation of men’s formal shoes, for example.

The overall look of the shops was upbeat and modern. Perspex stands were kept to a minimum and there were zig-zag tiled walkways between the carpeted areas. Most were fitted out by Clarks’ own shopfitters – as they are today. The store in Stratford, East London, sought to attract younger buyers, which explained in part why it had a 24-year-old manager and a 20-year-old senior sales assistant, both of whom ensured that one of its better sellers were the Clarks new air-cushioned casuals that had been the subject of a £300,000 national advertising campaign earlier in the year. Building on the slogan, ‘Travel with the World’s Most Comfortable Air Line’, the advertisements emphasised comfort and a degree of luxury and appeared in the national press as well as magazines such as Radio Times and TV Times, occupying prime positions on their inside or outside back covers. ‘With this air line, everyone travels first class’; ‘No other air line cruises at our speed’; ‘New heights of comfort for air travel’; and ‘Only one air line can fly you to the office’ were some of the captions, displayed in capital letters above pictures of the shoes.

Alan Devonshire, West Ham United’s star midfielder who won eight England caps, was reported to have bought a pair of Air-Comfort shoes from the Stratford store after suffering an injury to his heel and needing a shoe to speed his recovery – and before long, the whole of the West Ham first team squad was kitted out with air-cushioned shoes when travelling as a group to away games. This kind of endorsement was taken a step further and given another sporty twist in the autumn of 1985 when the children’s division launched a £500,000 back-to-school advertising campaign starring famous athletes and their mothers. One featured Sandy Lyle, who had just won the British Open Golf Championship at Royal St George’s, swinging a club, with an inset picture of him and his mother taken when he was a small boy. ‘We looked after his feet from the very first tee’ read the copy. Another showed the British number one women’s tennis player, Annabel Croft, administering a ferocious forehand: ‘She may get tennis elbow but she’ll never suffer from foot-faults.’

Any potential surge in sales from Clarks’ investment in retail was to be assisted by the new £3 million extension to the Bullmead warehouse, which attracted widespread attention in the media when it opened on 21 August 1984. HTV’s Report West programme devoted a full ten minutes to Bullmead’s computerised conveyor belt system that could sort 400,000 pairs of shoes a week. BBC’s Points West and the Financial Times also expressed interest, the latter running the headline: ‘Clarks automated shoe shuffle’. Working with a US-based automation company called Rapistan Lande, the system used laser scanners to read barcodes on shoebox labels, sorting up to twelve sizes, four fittings and five colours of shoe and then routing them to the correct van at what was called the ‘goods outwards’ bays. Speed was of the essence because Clarks operated a by-return replenishment service to its stockists. This meant up to 100 orders could be processed at any one time, with 50 chutes on one level and 50 on another. Productivity at Bullmead increased by up to 20 per cent and the new system meant 50 fewer people were working at the warehouse than there had been three years earlier.

A 1985 press advertisement for the new Air-Comfort shoes. The West Ham United football team was equipped with these for travel to away games.

But for all these new shops, advertising campaigns, star endorsements and technological breakthroughs, the business as a whole was in danger of stagnating. Indeed, some members of the board and several senior shareholders felt that stagnation already had occurred. New organisational structures were introduced, but traditional attitudes remained engrained. Daniel Clark, the chairman, appeared to some to be reluctant to bring in managers from outside the family and slow in sourcing shoes from abroad. But some would point to the constraints he faced by virtue of the number of family members on the board and working in the business, and the widely held belief that it was not possible to get the same level of quality from buying-in as you could from producing shoes in factories at home. Others took the view that if the factories in the southwest of England were to be competitive it would require taking out so much labour from the manufacturing process that quality would suffer.

The closure of factories should have happened faster, but Clarks was not alone in grappling with Britain’s decline as a manufacturing-based country. As Daniel noted in the 1984 Chairman’s Report,

… these actions have been difficult to decide on, involving as they do large numbers of people whose employment we have had to terminate, quite often people with long years of service to the Company.

As it was, arrangements were made during 1984 to close Dundalk, in Ireland, where shoes had been made since 1938 following an agreement with the Halliday family to produce Clarks under licence. This was a wrench. Clarks had taken full control of Dundalk in 1972 and relations with the company were close, with Daniel Clark, Lance Clark, Anthony Clothier and Malcolm Cotton all having spent time there as managers. Dundalk was something of a training ground where young executives could cut their business teeth.

In addition to the closure of Dundalk, what Daniel called a ‘disastrous year’ in America – due in part to the rising value of the dollar – led to the demise of three factories and all Peter Lord shops in the United States and a cutback at Big Sky, a chain of specialist stores selling leisure lifestyle footwear. One of the factories to shut was the original Hanover Shoes plant in Pennsylvania, which had opened in 1910 and at one time had employed 800 people, producing men’s formal welted shoes.

Clarks’ grip on the North American market in the mid-1980s was so shaky that the British Shoe Corporation expressed an interest in acquiring its retail interests there, but, instead, Clarks began courting Hanson Trust and Ward White, the latter being the company previously thwarted in its bid to buy K Shoes. William Johnston, who had been a prime mover in the original acquisition of Hanover some ten years earlier, was involved in these negotiations, but both approaches came to nothing. The price was deemed not right. Instead, some struggling Hanover stores were closed, while others moved to smaller units where rents were cheaper.

![]()

The 1984 shareholders’ report showed that the social responsibility component to the company was still very much alive, still central to the Clarks ethos. After being set up more than twenty years earlier, the Clark Foundation now had investments worth more than £3 million. That year, grants totalling some £120,000 were awarded to a variety of good causes. For example, Halfway House Bridgwater, a rehabilitation centre, received £31,000, and £13,000 was given to Nature Conservation. Smaller donations were made to a number of local charities such as Talking Newspaper for the Blind, in Plymouth, and the Somerset Youth Association. Daniel made a point of reminding the family about its Quaker commitment to helping ‘charities of a local nature, local that is to places of major employment by us’.

And despite rumblings from some shareholders about the company’s overall performance, pre-tax profits for the year ending January 1986 were more than £30 million, 43 per cent up on the previous year, although boosted by property sales and by so-called ‘pension contribution holidays’ whereby the company did not make any contributions to the pension fund because its assets exceeded the requirements of the pensioners.

This result was achieved on the back of what Daniel called a ‘most unsatisfactory situation’ in America, particularly in retailing. However, he stressed that of the 20 million pairs sold, all but 6.5 million were made in the company’s own factories. ‘Our policy is to concentrate our own manufacturing effort on products where we can offer something unique which can command a premium price. The pitfalls of resourcing abroad are legion,’ he told shareholders.

All and any changes to the board – and there were quite a few – between 1985 and 1987 should be seen in the context of the rise to power of George Probert, who had joined the board in 1980 on the acquisition of K Shoes. In the spring of 1985 there was a flurry of top-level appointments. Malcolm Cotton was sent to Australia and made a director of C. & J. Clark Ltd, and John Clothier was appointed chief executive of Clarks Shoes Ltd, a new company formed to unite manufacturing and retailing for the first time. He too was given a seat on the board. Of his appointment, Clothier says:

The thing is that I had always regarded myself as an outsider … I did not understand the family politics and my father [Peter Clothier] certainly never talked about it. I suppose I just tried to get on with turning a profit – although the fact that sales were good or not so good at that time was neither here nor there. It was the strategy of direction which was not being correctly spelled out.

Clothier’s task was exacting. The pressures on manufacturing were such that specification had to be taken out of the shoes to make them cheaper for consumers, but by doing this there was a danger of losing the essence of a shoe made by Clarks. Conversely, sourcing shoes from outside the UK became a growing imperative, but the options available were nothing like what they are today. China had not opened up economically and the Iron Curtain was still firmly in place.

Other new board appointees in 1985 included Alan Mackay, the finance director, along with David Hawkes, from K Shoes, who was made chief executive of K Shoes Ltd, responsible for the company’s manufacturing and retailing. At the same time, Probert was given the title of Group Managing Director of C. & J. Clark Ltd.

Jan Clark, Richard Clark and other members of the family remember Probert boasting that he would ‘get rid of the family’ – and he made a reasonable fist of it. At one point, according to the minutes of a meeting in 1986, he spoke about the ‘problems of having [family] board members who were not good enough’. Blunt and outspoken, Probert was not cut from the same cloth as his colleagues at K Shoes, who tended to be public school and ex-army. The son of a miner, he had risen through the ranks at the Kendal company after joining as a graduate trainee in 1948. He had been a shop assistant, a shop manager, advertising manager and then retail manager for the whole company, taking over from the long-serving Stewart Nicoll in 1962.

Probert had been a successful managing director of K Shoes. He insisted that all directors spend time selling direct to customers in the company’s shops and decreed that they should participate in any ongoing retail training known as Fitting Weeks. According to Geoffrey Holt, who also joined K Shoes as a trainee in 1948, Probert was a hard taskmaster. ‘It was never easy working for George,’ Holt is quoted as saying in K Shoes: The First 150 Years, 1842–1992 by Spencer Crookenden.

Immaculately dressed and always wearing formal, polished welted shoes, Probert found the informality at Clarks infuriating. It was not his style. Neville Gillibrand, while head of the men’s division, remembers attending a meeting in Street with Probert and other senior executives. It was due to start at 1 pm. Gillibrand arrived at 1.05 pm to find Probert leaving the room. Gillibrand, who still works as a ‘style consultant’ and is chairman of Clarks Pension Trustees, describes the scene:

He was spitting tacks. He said to me: ‘I just don’t understand the thinking around here.’ And I replied that it was the same thinking that showed how K could never make casual shoes and why Clarks could never make formal shoes. We were just completely different. He was from another world and it was hard to get on with him. We had opposing views about everything. George was a serious professional manager but his way of working was at odds with the Clarks culture.

Jan Clark had known Probert for a great number of years before the K Shoes acquisition. ‘He was a difficult man,’ says Jan. ‘He thought we Clarks always got where we were through nepotism – and I suppose we did. He despised privilege wherever he perceived it.’

Probert wasted no time in asserting himself as managing director. At first, he turned his attentions to the United States where he poured scorn on Jan’s decision in 1981 to move the US headquarters to new premises in Kennet Square, Pennsylvania, at a cost of $4 million. In a letter to a senior Hanover executive, he likened Kennet Square to an ‘ivory tower … very impressive but very remote’. Then he wrote a candid letter to Ron Mullins, the head of Cegmark International, a New York-based consultancy used by Clarks for issues relating to North America, bemoaning the stock problems in America that he estimated would cost the company $2 million.

Probert said that he would consult the rest of the board about the American operations and then make a decision.

My first inclination is to clear out the lot of them. On consideration, however, that seems impracticable. So I shall be faced with the delicate decision of whom to keep and whom to send packing in a situation where the right answer for every single one of them would be dismissal.

In fact, Jan Clark survived longer than Probert had intended. He was finally removed from his post as managing director of C. & J. Clark America Inc. in June 1986, but remained on the main board as a non-executive director until March 1987. It would seem that Jan was being held to account for the difficulties in North America, where trading losses of 21 per cent were announced by Big Sky in 1985, leading to the board agreeing that 31 of 60 Big Sky outlets would close. There was bad news, too, in South Africa – now part of Clarks Southlands subsidiary, which included Australia and New Zealand – when in January 1985 the factory in Pietermaritzburg closed, leaving 350 employees without jobs. This was blamed on the South African recession and when viewed in isolation was perhaps not too drastic, but retailing in both Australia and New Zealand was also on the slide, with the latter experiencing its worst year in a decade.

On leaving Clarks, Jan remained in the United States and did not set foot in England for five years. ‘When you get fired, you’re sore. There’s no way round that. It meant I had to choose a different course. My mettle was sharpened by the experience,’ he says. Jan went on to launch a successful real estate company in Delaware called Land Star Inc. and still lives in the US.

There were a number of proposals floated to change the make-up of the board. One was that Roger Pedder, Bancroft’s son-in-law, who had left the company in 1970 and who had wide experience in retailing, be approached to become an executive director, with his exact role to be determined once he had accepted the post. That got nowhere. In the meantime, scheming in the shadows seemed to become a way of life for some members of the family.

Daniel found himself stymied by a poisonous mix of board-level discord, national economic uncertainty and cripplingly high inflation. Even those who disagreed with some elements of his stewardship recognised that he was in an intolerable position. Some men might have walked away altogether on realising that their authority was perpetually being undermined by family tensions and corporate indiscipline. There had been an additional blow when Tony Clark, one of the family’s elder statesmen – and Lance’s father – died in February 1985. Tony, a former chairman of C. & J. Clark Ltd, was regarded as a stabilising and civilising force. He had been a magistrate, chairman of the local police authority and High Sheriff of Somerset. The death of this decent man was another blow to hopes of reconciliation among the warring factions. Bancroft, in a letter to his son, Daniel, shortly after this sad turn of events, spoke of Tony’s ‘shrewdness’ and described him as one of ‘the solid continuing family shareholders’ in Clarks.

Daniel needed support. In the autumn of 1985, he telephoned Malcolm Cotton in Australia to explain his predicament. Cotton jumped on a plane the next day – and remembers attending some ‘ferocious’ board meetings over the next few months. John Clothier, who, like Cotton, was newly appointed to the board, was aware of moves against Daniel, but says he was ‘not very clear what the benefits were going to be in replacing him’, particularly with Probert still in power.

‘Probert’s main interest was in driving manufactured shoes through our own shops and we had many heated disagreements about this,’ says Clothier.

His presence was always going to postpone the actions that were necessary. He was a bombastic character who simply did not see that the world was changing.

Daniel, shaken, but determined to battle on, recommended that Clive de Paula should join the board as deputy chairman in November 1985. De Paula was a family member by virtue of his mother, Agnes Clark, the daughter of Frank Clark. As a chartered accountant, he had broad experience in the City and had written a textbook on accounting which remained in print for many years. He was 70 when appointed a director. Daniel hoped he would provide some financial muscle and help sort out the future structure and hierarchy of Clarks.

Board meeting minutes show hostilities breaking out between shareholders and the executive. In June 1986, one minute spoke of a ‘total failure of communication between the Board and the family shareholding group … [causing] complete distrust on both sides’. There was talk of a two-tier board structure which would give shareholders more authority, but this was rejected. Various family shareholder groupings had begun to make their presence felt. A few months earlier, in a document dated 21 October 1985, the Whitenights group – so named because Whitenights was where Roger (Daniel’s grandfather) and Sarah Clark had lived on the outskirts of Street – produced a paper called ‘Summary on position of shareholders and on manufacturing and trading policies in the UK’. This missive tracked the decline of profits and called for a ‘rigorous new management with the highest qualifications and experience … the urgency of the task requires that this management is brought from the outside as it does not exist within the company’.

The Whitenights group included Stephen Clark and his daughter Harriet Hall, Stephen’s brother Nathan, the inventor of the Desert Boot, and Caroline Gould, whose mother was Bancroft’s sister. They concluded that the time had come to ‘convert our business and trademarks from being primarily manufacturing based to being retail and wholesale led, resourcing from our own factories and overseas’.

![]()

Members of the Clark family talk about Probert’s ‘Night of the Long Knives’ during 1986. In fact his cull, carried out with the tacit approval of a majority of the board, stretched over several months, during which he rid the board of three further family members. Officially, they all resigned; unofficially they were removed against their will. First to go was William Johnston in February, followed by Anthony Clothier in May and Clive de Paula in September. Ralph Clark retired as chairman of Avalon Industries, but remained on the board as a non-executive director.

But the biggest change came in September 1986 when Daniel himself finally stood down as chairman and was replaced in a non-executive capacity by Lawrence (Larry) Tindale, the deputy chairman of Investors in Industry Group plc, known as 3i. Richard Clark was instrumental in this appointment after consulting Robert Morison, who had been a partner in KPMG and who had advised companies associated with North Sea oil. Morison recommended Tindale and Bancroft was one of those who strongly supported this appointment – although reportedly he was heard to say many years later that it was one of the worst decisions of his life. Shortly after Tindale’s appointment, Morison himself was invited to join the board.

Daniel had endured a torrid time. Shortly after making his announcement to give way, he wrote to his cousin, John H. Clark, who had been working for the company in New Zealand. He was candid about his years in charge.

There was a basic ownership instability in the business arising from the now wide dispersal of family shareholding and the fact that although most family shareholders’ wealth is in the business very little of it is involved in a direct management or Board way. A couple of mediocre years allowed this instability to ferment …. I am sad, personally, that the contribution I can make is now so limited but pleased that I can now give more time to other things.

Daniel’s father, Bancroft, wrote to his son, thanking him for everything he had done in ‘conditions of extreme difficulty.’ He said:

Family shareholders are better off at the end of your time than they were at the beginning. That is indeed a solid achievement. They owe you a great deal …. You made bold acquisitions. Some of these have added great strength to the business, some have been harder to master.

Tindale, Daniel’s successor, was a seasoned institutional investor who, according to one board member, could ‘read a balance sheet with his eyes closed’, but lacked any experience or appreciation of the footwear industry. A trained chartered accountant, he had sat on the board of a number of companies, notably Britoil and Caledonian Airways, and been chairman of the British Institute of Management from 1982 to 1984.

‘The fact was that he was coming to the end of his career,’ says Roger Pedder, who finally was invited to join the board as a non-executive director in 1988. Pedder continues:

He spoke a lot about a return on capital when the issues were commercial not financial. He was the right appointment at the wrong time and his time as chairman delayed further what should have happened. He did not see what really needed to be done and he allowed the internal bickering to continue.

Pedder remembers attending a board meeting some months later when Nathan Clark expressly asked him to take along a plastic bag containing some Chinese shoes with a wholesale price of $10 a pair, almost half what it cost Clarks to make similar shoes in the UK. ‘The board meeting started off, as it always did, focusing on the troubles,’ says Pedder. ‘I’d never seen a shoe on the boardroom table since I’d been back. I said, “Excuse me, gentlemen, I think these are what we should be talking about,” as I laid the shoes out across the table. There was a frosty silence and nobody said anything and then we carried on as normal.’

Pedder describes the next few years as a period of endless deliberations and no decisive action. In a 2011 Harvard Business School case study, Clarks at a Crossroads, by Professor John A. Davis, Pedder is quoted as saying:

We were entrenched in the problems of being in uncompetitive, first-world shoe manufacturing and the response to this challenge had been, and continued to be, impossibly slow. The retail side of the business had grown to rival manufacturing, increasingly outsourcing its requirements, and building its own separate management and infrastructure, which created not only a dual overhead but also vituperative internal conflict.

![]()

A change at the top coincided with the introduction of a new logo. It was a subtle switch but an important one because it presented a unified corporate image, triggered in part by the need to do away with up to five different shades of green on Clarks’ distinctive boxes. The new logo incorporated the Clarks green to represent its heritage and tradition, and a modern grey, which had proved successful in point-of-sale material produced for the shops. This new colour coordination came shortly before an advertising campaign in the spring of 1987 to promote the ‘original’ Desert Boot, drawing attention to its many imitations by competitors around the world. For a number of years, the Desert Boot was far more fashionable on the continent than it was in Britain. Stylish young Italians were wearing them – though not necessarily the Clarks brand – with their Armani suits, and in Paris they were referred to as ‘Les Clarks’, even though they were often made by an entirely different company.

By 1987, Clarks was using Boase Massimi Pollitt as its advertising agency. Boase Massimi Pollitt’s brief was to do for the Desert Boot what advertising had done for Levi 501s and Doc Martens. Using the strapline ‘There is only one desert boot. Clarks. The original’, the ads were unquestionably sexual, with the photographs taken by Helmut Newton. One showed a man lying on his back draped over a wall near an inviting blue sea, a woman climbing on top of him, her knee pushed into his groin. Another featured a man leaning against the back of a tractor, his arms behind his head, as a woman stands suggestively in front of him. In both, the man is wearing a desert boot on one foot, nothing on the other.

The ads ran in selected fashion and style magazines such as the Face, the Wire, Blitz, Arena and the Manipulator. ‘The intention was to drop a small pebble in the pond and wait for the ripple to spread out,’ Graham Sim, a member of the Clarks marketing department, told the Courier. Mission accomplished. Almost all the national newspapers picked up on the ads, with the Sunday Mirror running a centre spread headlined ‘Hard Sell, Soft Porn’. The Sunday Telegraph was more measured, with a piece entitled ‘Easily Suede’, which concluded that ‘the desert boot has all the qualities of the style object … and a profile just begging to be raised’. The Today newspaper – which launched in 1986 and folded in 1995 – must have made for good reading in Street when it said ‘Move over Doc Martens, the desert boot is back’.

On another level, Clarks sought to shore up its hold on the children’s market, which it had so successfully built up in the post-war years, by launching ‘The Foot No. 1’, a brochure intended to look like a mini magazine, which was sent out to more than 5 million homes. This was the first time Clarks had tried direct marketing of this nature, showing parents and children up to 26 shoe styles so they could discuss what to buy for school before setting off to the shops. Perhaps prophetically, Clarks could not find a printer in the UK able to deliver the magazine on time and on budget, so went overseas and hired a company in Verona, Italy.

The pressure on the children’s division was enormous. It was the biggest earner for the company, maintaining a unique relationship with the consumer that still persists today. In the 1980s, there were some 300 different children’s styles at any one time, and of those between 40–50 per cent would be changed each year.

Karl Kalcher moved from Clarks Europe, where he was the territory manager for Germany and Austria, to become marketing manager of Clarks children’s division in the autumn of 1984 and later took over as children’s director. He was determined that children should engage with the product almost as much as their parents. ‘Can I have a pair of these?’ is what he wanted to hear children saying, rather than a mother deciding by herself what to buy her offspring.

A case in point was the Magic Steps sub-range for girls and Hardware range for boys. Magic Steps was aimed at four-to-eight-year-olds and was based around the idea of young girls wanting to be a princess. A little diamond appeared on the top of the shoe and when you turned it over there was a secret key encased in a small magnified transparent plug recessed into the heel. A television commercial based around a witch, the magical key and a princess proved hugely effective.

The biggest success for junior boys was the Hardware range, which featured a sole that looked like a computer games console. The styling cleverly combined child-friendly details and splashes of colour, but still within a form that was appropriate to go with school uniforms. The range was dressed up in a concept similar to space warfare video games and was backed by strong television advertising. It was massive in the UK and also proved to be the most successful launch of children’s shoes into Europe.

Clarks also re-launched ‘First Shoes’ (for infants up to two years old) in 1986. This was the bedrock of the Clarks children’s brand and where Clarks aimed to win over the hearts and minds of parents and lock them in as customers. The re-launch featured a strong, shrine-like point-of-sale package to give a clear focal point in the shop. The range was expanded to include more premium styles with softer leathers and a greater variety of colours and was a direct response to the leading European brands trying to enter the UK market.

Kalcher insisted on holding regular innovation meetings for his marketing and styling teams, when new ideas could be discussed and advanced. Watching programmes such as Tomorrow’s World and visiting the research labs at the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology was encouraged as a means of keeping abreast of the latest fastening mechanisms and the introduction of potential new materials.

Andrew Peirce was a product manager in the children’s division at that time, working with Kalcher. He remembers those days as both frenetic and stimulating:

Karl instilled a real sense of purpose. The challenge was demanding but the satisfaction levels were high. The reverberations went beyond the product and marketing departments. Expectations of quality and innovation from the factories [were] raised and the buying office was expected to become much more pro-active. Product was everything – the focus was on excellence and the challenge for a product range manager was somehow to know when to insist that we sacrifice that ‘little bit more’ so that we could get the shoes ready, at a commercial price, in time for the new back-to-school season.

Children’s shoes were central to Clarks’ business and to its standing in the minds of consumers. Other initiatives were more peripheral, more questionable – such as the decision to pay some £2 million for a majority interest in Rohan Designs plc. Rohan made outdoor clothing popular with walkers. It was started in 1975 by Paul and Sarah Howcroft, who lived in North Yorkshire, and by 1987 it had thirteen shops and was turning over £5 million a year. When the idea of buying Rohan was first raised, the Specialist Research Unit – the market research company headed by Peter Wallis – warned against it. One of Wallis’s partners, Colin Fisher, recalls a conversation when John Clothier told him that Clarks understood brands and that was why it would make a success of Rohan.

‘I told Clothier that Clarks did not understand brands – but it did understand Clarks,’ says Fisher, who in a remarkable turn of events is now executive chairman of Rohan. Clothier pushed on with his plan, telling the Courier that he considered the ‘Rohan brand as having the potential to be an exciting complementary business to the mainstream Clarks and K Shoe brands in the UK’. The press picked up on the story with The Times quoting Paul Howcroft as saying, in August 1988: ‘This will be a big leap forward for Rohan although there is a limit to how big you can get without compromising quality … I would like to see Rohan doing in its sector what Laura Ashley has done in theirs.’

David Hawkes, managing director of K Shoes, was an enthusiastic walker who already had several Rohan items in his wardrobe. He was made chairman of the company, but it wasn’t long before Rohan was wandering around Clarks like an orphan looking for a proper home. In 1996, it was sold on, but changed hands again in 2001, by which time Hugh Clark, Daniel’s son, and Fisher had joined Rohan. They found new backers in 2007 and today Rohan has 61 shops in the UK and turns over some £28 million a year. Hugh Clark is no longer involved with Rohan, but sits on the C. & J. Clark Ltd board as a non-executive director, representing family shareholders.

![]()

George Probert retired on 30 September 1987, the same year as James (Jim) Power was appointed a non-executive director. Power, who within five years would find himself in the thick of an escalating boardroom feud, had spent ten years with the Burton Group and eight years with British Home Stores, and was the director of finance and planning at Storehouse plc. Probert was replaced as group managing director by John Clothier, leading to another structural tinkering and some short-lived new appointments.

Lance Clark left the company in 1987, but remained a non-executive director. Neville Gillibrand, a popular figure with significant expertise in manufacturing and marketing, became managing director of Clarks Shoes and a director of C. & J. Clark International at the age of 43. Among his responsibilities was to strengthen the retail side of the business by expanding the number of dedicated Clarks shops.

‘The problem was that I had no experience of retail,’ says Gillibrand, ‘and this became quite obvious after a few months.’ And, so, in July 1988, Malcolm Cotton returned from Australia – where his responsibilities had expanded to include North America and Avalon – and was given back his old job as managing director of Clarks Shoes, with Gillibrand working for him as head of the Men’s and International Division (except for North America).

A K Shoes shopfront in 1989 – a familiar high-street sight throughout Britain until the brand disappeared in 2000.

In Australia, Cotton had gained considerable knowledge of retailing, but was at heart a manufacturer. Interviewed by the Courier shortly before assuming his new role, he hinted at the endemic problems between manufacturing and retail and said:

It seems to me that this complex process of changes associated with integrating our manufacturing, resourcing, wholesaling and retailing businesses has, not surprisingly, brought about some problems of control and balance. This has been affecting the company’s results and hence morale.

Morale took a further dive when Tindale announced the company’s results for the year ending 31 January 1988, which showed no improvement on the previous year, a set of figures saved only from further embarrassment by profits from the property side of the business. ‘This is the fourth year of static turnover, which obviously implies a down-turn in real activity,’ admitted Tindale. Operating profits for Clarks in the UK were down from £15.3 million the previous year to £7.1 million– although C. & J. Retail showed some gains. Tindale said the outcome was ‘well below’ what it should have been and promised to ‘undertake a major review of strategy’, drawing on the recommendations of McKinsey & Co., who, along with the Boston Consultancy Group, had been hired yet again as outside business consultants.

Central to that plan was concentrating efforts on three branded chains: Clarks, K Shoes and Ravel, with Peter Lord gradually being rebranded as Clarks. Lord & Farmer would confine itself to multi-brand retailing, and UK manufacturing would continue, but with the proviso that underperforming factories would close. Avalon Industries would cease trading, apart from some core activities directly affecting shoemaking in the West Country – a bitter blow given the historic links with Avalon going back more than a century. On the continent, France Arno would be disposed of and a close eye kept on North America, where profits were ‘unacceptably low’.

The worse-than-imagined results fuelled more bad blood between some family shareholders and the board. This forced Tindale to reassess his earlier position regarding a possible flotation of the company, something that had been discussed privately for many years and which caused concern among many family member shareholders who feared it would lead to a full-scale hostile bid.

As Tindale put it:

Although it should still be possible to obtain a listing for the ordinary shares in the spring of next year [1989], I do not think that it would be in the shareholders’ or the company’s interests so to do. It would mean going to the general public before the outcome of the major reorganisation had been fully proven and well before the benefits could be demonstrated in terms of earnings per share. The result might well be that the company would get off to a bad start as a listed company, not only in relation to the immediate price of its shares, but also in market understanding. If this were to happen, it would do a substantial disservice to both company and shareholders. I suggest, therefore, that the question of a public listing should be reconsidered when the successful results of the strategy are clear to see.

Tindale received a letter in January 1989 from the Street Family Shareholder Association, a grouping of like-minded shareholders. ‘This is the time for plain speaking,’ it began, before expressing grave fears for the future of the company. ‘We are not saying the value of the whole business will necessarily continue to drop. But we are saying that our members’ wealth is at risk. Furthermore we think our members are being asked to take too much on trust.’

Times were hard across the established UK footwear industry as the recession of the late 1980s took hold. Sears Holdings, the high street giant that had some 13,000 shops under the umbrella of its British Shoe Corporation subsidiary, was preparing to close 200 outlets, with the loss of 1,000 jobs, while opting to drop Curtess and Trueform altogether. Meanwhile, the likes of Marks & Spencer, Tesco and other supermarkets were showing a more determined interest in shoes, with Marks & Spencer claiming 6 per cent of the market in 1989, sourcing its entire range from overseas. By the end of 1989, two-thirds of shoes sold in Britain were imported.

‘I doubt there are any such firms that would not sooner make more rather than less in the UK, if it was commercially viable to do so,’ lamented Geoffrey Marshall, president of the British Footwear Manufacturers Federation, in a letter to Shoe and Leather News. But it was evidently not commercially viable to do so.

The board agreed that it was no longer possible to keep open Redgate 2, a Clarks closing factory in Street, or Isca, the company’s Exmouth factory, which produced women’s shoes. Both were phased out in 1988. Nevertheless, there was still no overall policy to stop production in Clarks factories. In fact, some – known internally as Centres of Excellence – were expanding. St Peters added an additional 66,000 sq ft of production capacity to its existing unit, at a cost of £6 million, but never managed to live up to the expectations that followed such a big investment, producing 300,000 fewer pairs than anticipated. St Peters, at one time spoken of in the same breath as the successful Bushacre factory in Weston-super-Mare and the Plymouth factories, closed in 1995.

Closures led to a greater reliance on buying in, something the company had been doing quietly – perhaps too quietly – since the early 1960s. In fact, back in 1975, the men’s division had appointed a manager to oversee the importing of formal shoes from Italy, canvas shoes from Korea and slippers from other manufacturers in the UK. By 1990, a third of all shoes – around 6.5 million – sold by Clarks were bought in, mainly from other manufacturers in the UK, Brazil, Portugal, Italy, South Korea and Taiwan. One factory in Italy was producing 600,000 pairs of men’s formal shoes for Clarks each year alone. Another Italian company was sourcing shoes from Romania and the Ukraine. Added to that list of supply countries were Spain, France, Hungary, Greece and Hong Kong. At that time, resourcing managers were organised geographically, with one person typically responsible for three or four countries, and Clarks had three offshore offices for this purpose – in Portugal, Taiwan and Hong Kong.

The experience in Portugal was different – or at least it became different. Clarks had seen how German footwear companies such as Ara and Elefanten had pioneered factories near Oporto, following the lead taken by Ecco and Mephisto. With labour costs lower than in the UK and with the Portuguese government encouraging inward investment after it joined the European Union in 1985, there was a strong argument for Clarks setting up a factory on a greenfield site in Portugal, but the board was not prepared to release the necessary capital or increase its borrowings in order to do so. Instead, in 1986, closer links were forged with Pinto de Oliveira, a shoemaking company which was already supplying 8,000 leather uppers to the Bushacre factory at an annual saving of £600,000 a year. This led to a joint venture – with each party having 50 per cent equity – through the formation of a new company called Pintosomerset Limitada, operating from a 14,000 sq ft factory at Arouca, a hilly farming area about 40 miles north of Oporto.

Two years later, when both Pinto de Oliveira and Clarks needed more capacity, Clarks opted to build a second factory for the sole use of Pinto de Oliveira and K Shoes – and did so to a roll of drums. At a ceremony on 3 December 1988, Mario Soares, Portugal’s president, officially opened the new plant at Castelo de Paiva, to the east of Oporto, and a period of training began, with the aim of supplying 30,000 pairs of uppers a week for the factories at St Peters, Barnstaple, Bushacre and K Shoes in Kendal. By June 1990, the factory was employing 600 people, of whom 85 per cent were women and 95 per cent were under the age of 25.

This was a big commitment for Clarks – and for Portugal. Certainly the powers that be in Portugal must have assumed that Clarks was in Portugal for the long haul. Clarks employees learned Portuguese, the local Portuguese learned English – and the mayor of Castelo de Paiva, Anteiro Gaspargas, clearly had high hopes of an enduring relationship with C. & J. Clark, announcing during a visit in the summer of 1990:

Clarks came to our region at an important time. Before the factory was built there was work here, but not enough. Many people travelled to Oporto, or even moved abroad to find jobs, but now, since the factory opened, more industry has been attracted to the area, bringing prosperity to what was a very agricultural part of Portugal.

The Clarks general manager in Portugal, Alf Turner, recognised the company’s responsibilities towards the region and its people. Speaking to the Courier, he said:

It is important for us to convince all of our employees as well as the community in general that we are serious and committed to our business in Portugal and that in the long run, both they and Clarks will benefit as a result of our work here.

But the Portuguese adventure failed to last. By 2001, it was over and Clarks was sourcing shoes made more cheaply elsewhere, notably from Vietnam.

Back home, by 1989 there had been ten further factory closures and it became clear that a new factory system was needed if young people were to be recruited in the way their parents and grandparents had been during Clarks earlier years. Piecework had helped workers earn good money, but there was a Dickensian whiff about it, encouraging output rather than quality. In its place, in 1989, Factory 2000 was launched and billed as a whole new system that introduced a flat rate of pay and concentrated more on quality than speed. It aimed to get the product right first time, with minimum waste – a leaner operation to compete more favourably with foreign competition.

Martin Peakman, Factory 2000’s project manager, assured employees that the new system would be ‘rewarding’, referring to both pay and working conditions. Something similar, known as the Toyota Sewing System, was introduced at K Shoes; this came from Japan, where the car colossus Toyota revolutionised the way it cut and stitched the leather seats on quality models. K Shoes discovered the Japanese system through its association with the US Shoe Corporation in Cincinnati and adapted it to its own factories in Kendal. One of its core principles was a move towards self-managed teams of four or five people producing an entire upper, with machinery reorganised into a horseshoe configuration.

‘Factory 2000 encouraged people to work in teams, but it turned out to be more expensive and did not improve the quality enough,’ says Paul Harris, who from 1988 to 1995 was in charge of the Barnstaple factory, where 20,000 pairs of women’s casuals were made each week. As Harris explains:

It was a desperate move in reaction to the recruitment pressures and the quality pressures, but it was not a magic formula. There was no disguising that manufacturing was becoming very difficult. We were fighting the tide and people sensed that more factories would close, but we also knew that the family had invested so much in those communities. And in any case, buying in shoes from abroad was not as easy as it sounds. Resourcing was not a tap you could turn on overnight.

Nor was restoring order between shareholders and the board. Tindale again stressed in January 1990 that a public quotation would be ‘fairer to the majority of shareholders’, but everyone knew that since it required a 75 per cent majority, it would never be achieved given the distribution of shares among key family members. Twelve months later, after the company bought in 561,007 ordinary shares at a price of 180 pence per share, Tindale changed his tune. In the Annual Reports and Accounts for the year ending 31 January 1991 he said:

The success of the buy-in dealt in large measure with the shareholders’ requests for liquidity, and market and general trading conditions would in any event prevent a successful share flotation in the near future. In view of the strongly held and expressed views of a substantial minority of shareholders, your Board has decided to postpone indefinitely moves to float the company and the existing method of twice-yearly opportunities to sell and buy shares will be continued.

Tindale also informed shareholders that Lord & Farmer was to close, with most of its shops reverting to either Clarks or K Shoes, and he warned that Ravel was experiencing turbulence. Looking ahead, he warned that things would become ‘very tough indeed’ for C. & J. Clark Ltd.

He was right – but he would not be around to witness it. By the summer of 1991, he had resigned, a decision taken in part because he was not in the best of health, although those close to him intimated that he was ground down by the wrangling between the board and shareholders, demoralised by the recession and fearful for the future of shoe manufacturing in Britain. He wanted out.

Before his departure, a group of family shareholders including Caroline Pym, Lance Clark, Caroline Gould, Harriet Hall, Nathan Clark and Roger and Sibella Pedder wrote a joint letter to Tindale telling him that it was

… in the interests of the management, employees and shareholders of C. & J. Clark that it remains a private family company … your successor should be someone who has the support of the majority of shareholders.

It went further, leaving him with a plan for the future, which they wished him to recommend to the board prior to his departure.

The proposal has the full support of ourselves and our Family shareholdings, representing an effective majority of the shareholding in C. & J. Clark. If required we will vote to support them at a shareholders meeting.

It was a radical plan. The proposal called for Lance Clark to be appointed chairman on 26 April 1991 at the Annual General Meeting; Roger Pedder would become vice chairman and John Clothier would be given ‘full support’ as chief executive, subject to achieving certain fiscal goals by 1993 – ‘a profit after interest representing 20 per cent of capital employed’. There were eleven points in total. Under the heading ‘Policy’ it said, with no apparent irony: ‘There is no intention behind these changes to interfere with operational management of the company.’

A record of Tindale’s response does not exist. But this audacious manoeuvre came to nothing. Instead, headhunters were deployed to find a successor to Tindale from outside Clarks and they identified Walter Dickson as the man for the job.

Dickson, who was of Scottish descent, might not have known one end of a shoe from another, but he was well versed in the vagaries of working for a family firm with a long history and proud tradition. He was known as ‘the man from Mars’. And for good reason, since he had worked for the American-owned confectionery company for 25 years, joining in 1962 from Procter & Gamble as national sales manager and ending up as president of Mars Europe. Along the way, he was variously sales director and then managing director of Pedigree Pet Foods, a subsidiary of Mars, and managing director of Mars Confectionery.