Clarks Village, the first retail outlet centre of its kind in Britain, was opened in August 1993 and is now one of Somerset’s most popular tourist attractions, containing nearly 100 high-quality stores.

THERE WERE NO RECRIMINATIONS. No gloating from the winners, no sulking from the losers. Polite handshakes were exchanged between rivals on the board. Barings, the merchant bank representing Berisford, issued a short statement expressing its regrets, and Alan Bowkett said he was ‘saddened’ by events. Walter Dickson promised that the board would ‘work towards achieving agreement on how best to take advantage of the great strengths of its [Clarks] brands’. On a personal level, he would consider his position.

Hugh Pym’s wife, Susan, was in tears. Harriet Hall simply turned to Alan Bracher, the SHOES group’s legal adviser, and said, ‘I’m going to give you a kiss, Alan.’

At the time of the vote, Clarks was over two thirds owned by the family, with the remainder owned by outside institutions, the Clarks pension fund, employees and ex-employees. A comfortable majority of the family had voted against selling the company, while the vast majority of the non-family had voted in favour of selling.

An agreement had been made that whatever the result both sides would observe a two-week cooling-off period. The less said the better was the implication – although those involved in what would become a new corporate governance structure began work immediately. Even the media seemed subdued, but perhaps that was simply because a long-standing Quaker family company being sold would have made a better story.

On 18 June 1993, Dickson wrote his final letter to the Clarks shareholders, confirming that an independent chairman would be appointed in due course as his successor, plus two non-executive directors. In accordance with the SHOES commitments, he said a family shareholder council would be established by 31 October, and that this council would appoint two family members to sit on the main board as non-executive directors by the end of the year at the latest. It was agreed that the board of C. & J. Clark Ltd would not only have fewer family members but would be smaller in general. He confirmed that Harriet Hall was to serve as the shareholder council’s first chairman.

In addition, and as promised, the company would prepare itself in ‘an orderly way’ for a Stock Exchange listing within five years ‘dependent on a range of factors’.

Two days later, Dickson announced his resignation.

Roger Pedder was made non-executive chairman while a new chairman was recruited. Norman Broadbent, the firm of City headhunters, was commissioned to find suitable candidates and arrived at a shortlist of names drawn from the City. None met with the approval of family members on the appointments committee. They did not want a Walter Dickson Mark II and argued strongly in favour of their preferred candidate, Roger Pedder. Then, on 6 November, it was announced that Pedder, who was 52, had been offered the job – and had accepted. Upon his appointment, Pedder stood down as managing director of Pet City, the company he had jointly founded and which went on to be bought by the US group, PetSmart, for £150 million in 1997.

‘We knew he had experience as a chief executive and was good at running things, but he had never been a chairman and so it was a risk – a risk we were willing to take,’ says Richard Clark.

Shortly after Pedder’s appointment, Daniel Clark stood down as a non-executive director after 26 years on the board. He went on to pursue his interests in academia, deriving great pleasure from his research and writing. He gained a Masters in Archaeology (Environment) from London University (Birkbeck) and followed up with a doctorate at Bristol University, where the title of his thesis was ‘Insular Monument Building: A cause of social stress? The case of pre-history Malta’.

Earlier in 1993, on 23 July, Daniel’s father, Bancroft Clark, had died at the age of 91. Bancroft had always said he hoped there would be no obituaries in the national press following his death, but obituaries duly appeared. The Times called him ‘the Grand Old Man of the British Shoe Industry’ and a ‘giant of a man in all respects’ who would wander the factory floor in a white coat ‘pouncing on the smallest error and ripping up defective shoes with his bare hands’. The Financial Times credited him with developing the famous Clarks foot gauge and said ‘if the shoe fits, wear it’ would be a suitable epitaph for the man who led the company for 25 years.

Meanwhile, there were no major changes to Clarks’ senior management – not yet, at any rate. John Clothier remained group managing director and Malcolm Cotton was made deputy managing director. In his first Annual General Report, for the year ending 31 January 1994, Pedder announced that despite the ructions earlier in the year, results were an improvement on 1992, with profits before tax of a little over £20 million compared with a virtually break-even position for the previous year.

Clarks was still a shoe manufacturer, wholesaler and retailer. It had fourteen factories in the UK, five in Australia, three in North America and two in Portugal, and in the UK it had shops trading under the Clarks, K Shoes and Ravel names. But no one was under any illusion that the structure of the company could continue much longer in its current form. Indeed, there was a question mark over Clarks’ whole raison d’être, not least because in Britain there were 25 per cent fewer shoe retailers than five years earlier and the buzz word was ‘discounting’. UK discount stores were claiming a 4 per cent market share, a frightening figure for a quality shoemaker such as Clarks with high overheads, and which itself could only boast 5 per cent of the market, the same percentage at the time as one of its main rivals, Marks & Spencer. But this was nothing compared with what was going on in the USA, where discount and outlet stores were growing at an alarming rate, seizing 8 per cent of the overall shoe market. No wonder, then, that Bostonian, the US business owned by Clarks, recorded profits of under $5 million on sales of $110 million for the year ending January 1993.

‘We simply were not competitive,’ says Pedder. ‘It was obvious that the whole notion of the company had to change and become retail-marketing led.’

But there was one area in which the company was competitive: Clarks Village, the outlet store in Street that was opened in August 1993. John Clothier was the driving force behind this venture – the first of its kind in Britain – assisted on the ground by Chris Pleeth, who worked for Clarks Properties. K Shoes had opened factory shops in Kendal and Doncaster in 1992 and everyone had been pleasantly surprised by the results. This was confirmed when Clarks commissioned a survey of holidaymakers in Cumbria, showing that 66 per cent of those polled put shopping at the top of their list of preferred activities, way above fell walking.

The factory outlet experience in Street was to be on a bigger scale than in Kendal, and Clothier says his determination to push it through was born, in part, from a moment of frustration.

‘I came out of a board meeting one day in a rage over something or other that had been said. I thought the best thing to do was light a cigarette and go for a walk around the block. I passed by the abandoned factories and it was clear we should use them to sell certain lines at discount prices.’

Both Clothier and Pleeth went on fact-finding tours to the USA, where factory outlet villages often occupied up to 300,000 sq ft of space in vast business parks or dedicated malls. During one of these trips, Pleeth attended what was billed as an ‘Outlet Conference’ in New Orleans, after which he recommended that Clarks Village in Street should have more of a rural atmosphere about it, replete with a sit-down restaurant, outdoor play area and various picnic spots. Shopping at Clarks Village offered a family day out in a rustic environment. The number of visitors predicted for the first year was 850,000 – but this target was reached within just four months.

Plans were then immediately put in train to expand Clarks Village. The Next to Nothing store was joined soon afterwards by Laura Ashley, Benetton, Thornton’s and Black & Decker, paying no ground rent but giving Clarks a percentage of their takings. In 1995, Clarks Village won an Award for Innovation from the British Council of Shopping Centres.

Such was its success that the board realised it needed to be run by a management that specialised in such businesses. And it was also agreed that selling the village made financial sense. MEPC, a publicly quoted property company, was the favoured buyer, but the disposal of what was officially called The Factory Outlet Centre Business required an EGM of shareholders. This was held on 21 May 1997 at the Wessex Hotel, within walking distance of Clarks headquarters. In the past, Clarks EGMs had not always been happy events, and on this occasion too there was some opposition to the sale, but in the end it went through with a 75 per cent majority. MEPC paid £80 million for the three factory outlets in Street, Kendal and Doncaster.

Clarks Village, the first retail outlet centre of its kind in Britain, was opened in August 1993 and is now one of Somerset’s most popular tourist attractions, containing nearly 100 high-quality stores.

Some commentators speculated that the sale was part of a Clarks strategy leading up to a stock market flotation, given the commitment to float within five years of the 1993 EGM if conditions were right. However, during an interview with the Financial Times a month earlier, Pedder had said Clarks would continue to concentrate on its core business and was not focused on going public:

The family shareholders are happy, and it is not a subject of debate. We would consider it if market conditions came right and if we felt it was the right time to raise funds for expansion. At the moment we don’t need to.

Today, Clarks Village is visited by four million people a year and is one of Somerset’s most popular ‘free’ tourist attractions. Marks & Spencer was a new addition to the village in 2002, occupying the former Grove factory, since when the number of stores housed in various buildings just off the High Street has reached nearly 100, with parking for 1,400 cars and 10 coaches. The village is now owned by Hermes and managed by Realm Ltd.

The sale of Clarks Village was a good example of the newly formed family shareholder council – known officially as the Street Trustee Family Company (STFC) – working effectively. The council takes the form of a company limited by guarantee. Joining involves giving the council power of attorney to vote on behalf of the shareholder’s shares – a block vote, in effect, subject to various safeguards, rather than family shareholders voting individually. Before using the proxies it holds, the council informs all members of the way in which it intends to vote on any issue, allowing members to withdraw their proxy if they so wish.

Members of the STFC board are elected every four years by the shareholders, with each member of that board requiring the support of shareholders owning 4.5 per cent or more of the equity of C. & J. Clark Ltd. The council’s two nominees on the board of C. & J. Clark Ltd serve as non-executive directors, and communication between the boards of C. & J. Clark Ltd and STFC is channelled through the Clarks chairman, with meetings held four times a year. The shareholder council has its own secretariat paid for by the company.

‘I saw my job as keeping the shareholders united and off the management’s back, but at the same time the shareholder council was and is a way of holding the management to account,’ says Harriet Hall, STFC’s first chairman.

There were family members at the time, however, who feared the shareholder council would be a licence for the different factions to carry on squabbling. This did not happen. Hall says it was ‘immediately encouraging that all those who wanted to sell the company opted to join the council rather than staying outside and sniping. Some people thought that once things had settled down councillors would stop attending, but this has never been the case. In fact, numbers have increased through allowing younger family members to attend so they can gain experience of looking at the company’s performance.’

The family shareholder council held its first meeting on 5 February 1994. Back row (left to right): Jan Gillett, Tom Clark, Adrian Little, Hugh Clark, Sibella Pedder, Gloria Clark, Ben Messer Bennetts. Front row (left to right): John Aram (secretary), William Johnston, Charles Robertson, Harriet Hall (chairman), Ben Lovell, Sarah Clark, Caroline Pym, Nathan Clark, Cyrus Clark.

Indeed, in a 2012 survey of family shareholders, one question asked was ‘How long do you intend to be a shareholder of Clarks for?’ The response of 89 per cent of those polled was ‘My lifetime.’

Hall brought to the role knowledge of family members and a clear focus honed by her legal training. She had been a key figure in the group that had kept the company independent, and so had a lot to lose if the council did not do its job.

John Aram, who had worked at Clarks for more than twenty years, was chosen as the STFC’s first secretary. He is unstinting in his praise for Hall, saying that ‘many people thought the council was doomed to fragment’, but that she ‘somehow kept all the factions working harmoniously together – an extraordinary achievement’.

From the council’s inception, it was important that the past bickering among and interference from family members did not obscure the fact that serious and legitimate concerns about the future of the company had to be addressed – and quickly. ‘I knew that the board and management must be clear that shareholders as a united force required action to restore the company to profitability,’ says Hall.

Family firms on the scale of Clarks were thin on the ground in Britain by the mid-1990s – a theme that had been picked up by BBC Radio 4’s In Business programme on 1 May 1994. Pedder was invited to the studio and was asked by the presenter, Peter Day, ‘Don’t you find this family company a difficult one to manage?’

Pedder replied, ‘I think it obviously can be because of the troubles we’ve had. But if you look on the positive side, it has tremendous dedication, both from the family and from the workforce, and has an identity of many years of dedication which other companies probably don’t enjoy.’

‘Yes, but if you’re trying to manage a company like this then the family tends to get in the way,’ suggested Day.

‘Not necessarily,’ replied Pedder. ‘I think it is a misapprehension to think the family’s always in the way … I think the difficulty is to both own and manage directly. And it’s that which we’ve sorted out over the last year.’

Sir John Harvey Jones, the businessman well known at the time for his Troubleshooter TV series, was asked to contribute to the programme and pronounced that ‘the transformation of family firms in this country is the key to our economic revival’.

In the case of Clarks that transformation was still to come, and perceptions of the company remained unflattering. For example, Janet Street-Porter, then head of the BBC’s youth programming, was quoted as saying that the corporation for which she worked was in danger of becoming the ‘Clarks shoes of the multimedia world, something that your mother would buy for you but you’d never choose for yourself’.

Meanwhile, Pedder, who had always taken the view that poor management was as much to blame for the Clarks slump as rising costs and general market conditions, found himself telling shareholders that 1994 had been a ‘real disappointment’, with net profits before tax down on 1993. But he was also able to assure them of moves that were aimed at arresting the slide.

Two factories – St Peters in Radstock, Somerset, and Marlinton, in West Virginia, USA – were to be closed, and further cuts were planned in 1995 to make the company ‘better focused and highly cost effective’. The St Peters factory had been the largest single employer in the town (population 5,000) for almost forty years, its closure representing a dark day for the local community. The decision was also taken to close the K Shoes offices in Kendal and merge the operations of Clarks and K in Somerset. This meant the arrival in Street of Peter Bolliger, who had been appointed managing director of K Shoes in the summer of 1994.

Bolliger was a big beast in the shoe jungle. Born and raised in Basel, Switzerland, his CV included a period with the respected Swiss shoe business Bally, before he moved to South Africa to join a footwear company associated with Carvela shoes, now part of the Kurt Geiger stable. It was while in South Africa that he crossed paths with Mohamed Al-Fayed, the owner of Harrods, who wanted to bring him to London as his new managing director.

‘He told me he liked the Swiss and that a lot of his money was in Switzerland,’ says Bolliger. ‘He also said he liked shoe retailers.’

Bolliger stayed at Harrods five years, eventually falling out with Al-Fayed in spectacular, but not unusual fashion. When he announced he was leaving, Al-Fayed’s then director of public affairs, Michael Cole, put out a statement stressing that Bolliger’s departure was ‘not voluntary’. Then, referring to Al-Fayed’s unique proprietorial style, Bolliger was quoted by the Mail on Sunday on 24 April 1994 as saying: ‘You simply can’t have two kings in an organisation like Harrods … I’m confident I will get another job … I know President de Klerk [of South Africa] and he’d be grateful for my skills.’

When he came to Street from Kendal, Bolliger was initially put in charge of the women’s division and was ‘quite anxious because nothing in Street seemed to have changed,’ he says. ‘The old guard was still there and there was a lot of talk about what we should do but not a great deal about how to go about it.’

Pedder was about to make moves to change that. He realised only too well that the issue of Clarks’ competitiveness had still not been properly addressed – and he knew that tinkering at the edges was not the answer. He was well aware that the wage gap between Clarks’ employees and their Third World counterparts could not be bridged. A Clarks factory worker in the West Country made on average £15,000 a year; a worker in India made £300. This glaring disparity became all too evident when Pedder and Dudley Cheeseman, the Clarks production manager, flew to India towards the end of 1994 looking at factories in Ambur, the capital of India’s shoemaking, in the south of the country. In one factory, they noticed men’s shoes with Marks & Spencer labels in the footbeds. Pedder asked what was the factory price for the shoes and quickly worked out that if Clarks were to produce something similar in the UK, it would have to charge customers £34.99 a pair to stand any chance of covering its costs and making a small profit. M&S was selling them at £29.99. The owner of the factory then asked if they wanted to see another factory nearby, which was using equipment inspired, as it happened, by machinery used by Clarks back at home.

‘Who are you making these for?’ asked Pedder, on seeing rows of wellmade casual shoes.

‘Marks & Spencer, of course,’ said the owner.

![]()

The Indian trip convinced Pedder of the need for change at the top of Clarks, and so, with a view to bringing in a new CEO, he stood Clothier down as chief executive with effect from January 1995, bringing to an end the Clothier family’s long day-to-day association with the company.

‘I had been in the thick of it for seven years and I knew what was coming,’ says Clothier. ‘Some people can take the task of sacking large numbers of people lightly. I wasn’t one of those. I did not want to sack the people my father [Peter Clothier] had hired – even though I knew it was necessary. In the circumstances, it was the right time for me to go.’

He was replaced by Malcolm Cotton on an interim basis, who was given the title of Managing Director (operations). Pedder became executive chairman.

The search for a new CEO gained impetus when Pedder was reading a magazine on board a flight to Boston. The article was about up-and-coming British managers who were all under 40. One of these was Tim Parker, who by then had led Kenwood’s management buy-out from Thorn EMI before grooming the company for a flotation in 1992. He was described as ‘young, brash, well-educated and known to stick his neck out’.

Contact was established and he was appointed on 29 September 1995, although he would not start until January 1996. Kenwood’s shares fell 10p on the announcement.

‘I met Tim in Salisbury and he said there was not going to be room for both of us at Clarks and I accepted that,’ says Cotton. ‘I realised the advantages of bringing someone in from outside.’

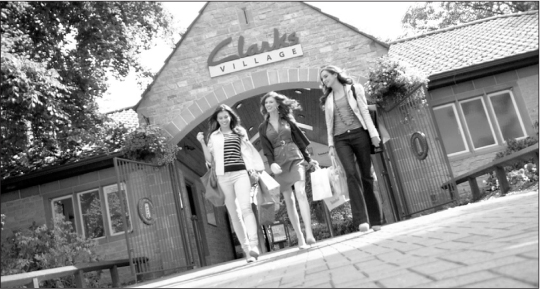

Parker was still only forty when he eventually got his feet under the desk at Clarks. But he had packed those years with experience. Educated at Abingdon School and Pembroke College, Oxford, where his degree was in philosophy, politics and economics, he had toyed briefly with the idea of a career in politics, chairing the Oxford University Labour Club and later working at the Treasury as a junior economist when Denis Healey was chancellor. But it was not long before he swapped the public for the private sector, taking an MBA and moving seamlessly towards supporting the Conservatives.

As part of the 2011 Harvard Business School case study, Parker said:

I was looking around for a new challenge. I felt this was a really interesting opportunity, not least because I quite liked shoes and I thought, well, if I can go and work in this company and help them to make more shoes that I would actually like to buy, then that would be good.

Regarding the task at hand, he said:

Clarks had market share. There are two key determinants for room to manoeuvre. One is scale and the other is relative scale. So, if it’s big, it means there’s a lot you can change. If it’s bigger than its nearest competitor, it means that you’re in an even stronger position. And Clarks had both of these things in retail.

Tim Parker, recruited from outside the company by Roger Pedder, radically restructured the business as chief executive from 1995 to 2002.

Pedder said in the same Harvard study that Parker’s personal situation was ideally suited to a family firm such as Clarks:

He wasn’t of the family, wasn’t of the area, didn’t come from the shoe business. He didn’t have any alliances. He didn’t have any people to protect. He wasn’t in debt to anybody. All positives, because he didn’t bring any baggage with him. What he brought was an objective mind about what needed to happen in an economic situation.

Parker had done his homework, and within six weeks presented his first report, ‘Strategy, Structure and Management’. It was a plain-speaking, no-nonsense critique of the company with some far-reaching conclusions. And not always easy reading:

The main reason for Clarks failure in recent years has been, frankly, management incompetence on a massive scale, leading to, at best, inertia and, at worst, bad decisions. The answers to these problems are to be found in the culture of the company and its personnel policies … the location of the business in a relatively isolated part of the West Country, with a very pleasant lifestyle for those of middle-class income, has fostered a comfortableness and a cloister-like sense of detachment reminiscent of an Oxbridge college.

Parker railed against what he called the ‘civil service mentality’, whereby pay and benefits continued to rise and ‘incompetence’ was rarely tackled. He admonished the company for the way it had allowed parts of the business to ‘deteriorate into baronies’, fostering a culture whereby ‘high individual interests’ had ranked above those of the business. ‘Compromises over control mean that no one is really responsible for anything: marketing can always blame the factories; the factories can always blame Indian uppers and retail can always blame poor results on non-delivery,’ he said.

What must have stung the management and the workforce most was how he used the company’s values as a stick with which to beat it.

What is quite incredible is to hear the well-intoned mantra of ‘integrity’. What integrity is there in a management which looks after its own, fails to grapple with the key strategic issues facing the business, and, as a result, saddles the company with a huge cost burden and horrendous results?

Parker laid out some key strategic goals and outlined what would be required to achieve them. Clarks must become a retailer for ‘middle England’ at home but a premium casual brand overseas. This would require a lot more ‘sparkle’ going into the research and design side of the company and then, once the product had improved, there would be an investment in advertising, focusing on one or two specific markets. Some ‘really original thinking’ was required to address the ‘pedestrian’ children’s business, with a view to making it a creditable international brand.

On manufacturing, he said it was not clear how many factories were viable but he stopped short of calling for their complete closure. ‘If alternative sources are available at considerably lower cost we must consider closure. It is doubtful whether we will end up with anything other than a handful of plants in the UK.’

Within ten years of Parker taking over as CEO, every single Clarksowned factory in the world was to be closed.

Parker’s changes were comprehensive. He issued a decree that jackets and ties were not strictly necessary in Street and he pressed for more flexible working hours, keen that staff should not always feel duty bound to clock off at 5 pm precisely.

Putting his new management team in place, he made Bolliger his most senior lieutenant as UK operations director. Among others in key roles were Neville Gillibrand, who became international brands director, and Royston Colman, who was made manufacturing director.

For many long-serving managers, Parker’s withering indictment of the past was hard to swallow. Those who found it hardest were the professional shoemakers who had risen through the ranks; in many cases they had been employed by Clarks all their working lives and they took pride in the product.

Kevin Crumplin, who, as director of personnel and a member of the main board, had been keen to recruit Parker, experienced mixed emotions. ‘I did not like Parker personally. I did not care for his arrogance and lack of respect for what the shoemakers had achieved,’ he says. ‘But I accepted that the transformation had to happen. Sadly, you sometimes need a person like him to do what is required. My position was that I had helped deliver what the board and the shareholders wanted, but I didn’t want to stick around any longer.’

Crumplin resigned in February 1996, just days after Parker produced his damning report.

Royston Colman’s appointment as manufacturing director effectively meant he was in charge of closing down the factories – and by the end of the process had made himself redundant.

‘Tim used to tell me that I had the worst job because everyone else was building while I was destroying,’ says Colman, adding:

And the speed with which we stopped manufacturing increased as confidence in resourcing grew. It wasn’t always pleasant, but I hope I did it with as much sensitivity as possible. I suppose over the years I helped to get rid of 5,000 people, many of whom I knew personally.

Colman was one of those who went with Parker to inspect shoe factories in China during 1997. Pedder, Bolliger and Mark McMenemy, who was hired from Marks & Spencer to succeed Alan Mackay as finance director, were among others on that trip.

‘We saw some state-of-the-art machinery and some very professionally made shoes produced at a fraction of the cost,’ says Colman. ‘It was obvious to me from that moment that my role was to tick off our factories by closing them down as fast as possible.’

Colman himself left in 2000, although Parker brought him back briefly on a part-time basis to shut one of the Portugal factories in 2001. After that, he threw himself into charity work.

The first factory to close under the Parker regime was in Bridgwater, followed by those in Shepton Mallet, Plymouth and Askam, Cumbria, in July 1996. In Australia, the factory in Preston was shut down, along with Marlinton in the USA, where profits for the year ending 31 January 1996 had ‘effectively collapsed’ due to a ‘combination of over-optimism, poor marketing and a failure to control the sales function’, as Pedder put it in the annual report.

The situation in North America was dire. To address this, Bob Infantino, who had been recruited in 1992 from Rockport, the Boston-based footwear company, was put in charge of the whole North America operation – Clarks of England, Bostonian and Hanover – and slowly the business on that side of the Atlantic started to improve. The entire North American operation now came under the title of Clarks Companies North America (CCNA). In the USA, more so than anywhere else, consumers perceived the Clarks brand differently from their British counterparts. Parker was happy to allow this, and he gave Infantino considerable freedom to manage the North American operation in his own way.

Encouragingly, a year later, in 1996, Clarks of England was named winner of the Company of the Year award by Footwear News, a specialist industry publication in the USA, and twelve months later the North American operation posted trading profits of $16.7 million, more than double what was achieved in the previous year. This was mainly as a result of improvements in the wholesale side of the business, and although retail was still disappointing, Parker felt the prospects in North America ‘had never been stronger’. He was proved right. From 1995 to 2001, sales increased by 57 per cent, with operating profits up five-fold, achieved in part by introducing highly competitive discounts to attract new consumers, a strategy that caused difficulties for some of Clarks’ weaker competitors.

Back home in Street, a quarter of the Clarks workforce in the town (more than 500 people) lost their jobs, largely as a result of the brand and retailing buying teams working as one unit. Parker was unequivocal:

If you want to make things happen in a business with problems, you have to accentuate the sense of crisis. Stress that there is no alternative. It is fear that normally drives people to take action and to change things. There was a hope [on the board and in the Council] that you might be able to retain a portion of the business in the United Kingdom, but slowly it dawned on everybody that it wasn’t commercial. Our pricing was completely wrong. But more critically, we couldn’t make the shoes the market really demanded.

Old perceptions of Clarks persisted. In September 1996, the Independent ran a feature with the unfortunate headline: ‘Do we need Clarks shoes?’ To which the answer, some 1,500 words later, came as a resounding ‘no’. Perhaps in a spirit of mischief, the journalist, Jonathan Glancey, then the paper’s architecture and design editor, wrote:

To my eye, most Clarks shoes are ugly, bland and unstylish. Clarks are not to be taken seriously by adults. And what about the sort of schoolteacher who used to wear Clarks Polyveldts? How could any schoolboy aspiring to zip-up leather boots from Elliots, Toppers or Kensington Market take seriously a teacher who wore omelettes for shoes?

He had some ammunition left strictly for Parker:

Clarks may well survive and even prosper with new professional, business-school-educated management, and good luck to it. But, if you are a grown up, save up for a decent pair of leather shoes (wear bin-liners tied with string if you have to whilst doing so), learn to polish them and enjoy their patina and comforting natural smell.

His advice went largely unheeded, as results for 1997 across the whole group finally began to reflect Parker’s restructuring of the business. Profits were up to £39.4 million from £33.6 million the previous year, the best figures since 1987.

Parker called it a turning point, and said a crucial difference was that Clarks was making shoes its customers wanted to buy rather than the shoes ‘we wanted to make them’. It was also abundantly clear that Clarks shoes were too expensive to make in England. Cost-cutting not only affected the production process but meant there was less money to create new styles. This cemented Parker’s objective to change the company from being a manufacturer and wholesaler with some retailing to becoming a retail-led business with some wholesaling. Never knowingly understated, Parker told shareholders at the start of 1998:

We have three very clear objectives: to be the No. 1 shoe retailer in the UK; to be the No. 1 children’s shoe brand in the UK by a factor of at least two over our nearest competitor; and to be the world’s No. 1 shoe brand outside the athletics arena.

His cause was helped by the collapse of the British Shoe Corporation. Ten years earlier, one in four pairs of shoes bought in Britain was sold in a BSC store. By 1997, that figure was less than one in ten as the late Sir Charles Clore’s chain of high street shops began to unravel. Freeman, Hardy & Willis, Mansfield and Saxone were all no more. In fact, the only recognised BSC names still trading were Dolcis and Stead & Simpson.

Parker’s commitment to increased advertising paid dividends – despite a tricky episode in April 1997 when the company was forced to abandon a campaign showing children walking on a railway track and then sitting on the lines. There had been several recent deaths involving children and trains, and the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents took a dim view of the posters. Clarks claimed that the line in question was disused because weeds were growing through the sleepers, but admitted an ‘error of judgement’ and withdrew them.

In the autumn of 1997, Clarks’ cutting-edge advertising agency, St Luke’s, came up with the strapline ‘Act your shoe size, not your age’ for a series of TV ads that ran for six weeks. Sections of the media immediately picked up on Clarks’ efforts to shed its old-fashioned image, with the Financial Times making the point, correctly, that Clarks was regarded as considerably smarter and more fashionable overseas than it was in the UK.

Parker told the paper:

If you go for a conventional campaign attempting to look younger, you’re in danger of losing a large chunk of people at the older end of the market. We wanted something with broader appeal that says you can buy our products without any residual feeling of buying into something institutional.

A stroke of good fortune came Clarks’ way when Richard Ashcroft, frontman of The Verve and not exactly the institutional type, wore a pair of Wallabees – first launched in 1966 – on the cover of the band’s massiveselling 1997 album, Urban Hymns. And it could have done no harm that Parker, with his shock of curly hair and propensity for wearing jeans and no tie – and who played the flute in his spare time, and drove a Porsche – was something of a dashing figure.

![]()

Profits rose and factories closed. By the end of 1999, there were only four UK manufacturing plants left – Ilminster, Barnstaple and Weston-super-Mare in the West Country, and one in Kendal in the Lake District. By 2005, there would be none.

Re-organisation continued apace. Ravel, which had been struggling, was incorporated into the main retailing division based in Street, and more than 40 per cent of Clarks and K Shoes stores were fitted out in new designs aimed at dealing with what Parker called the ‘dowdy image’. He felt there was too much green associated with the Clarks logo and its shops. The idea was to introduce white and beige, a brighter, cleaner and sharper presence in the High Street.

At board level, Harriet Hall, who had been central in establishing the new governance structure following the Berisford bid fall-out, became a non-executive director of the board in 1999, replacing Caroline Gould. Lance Clark, meanwhile, one of the longest-serving C. & J. Clark Ltd board members, was replaced as the second family director by Ben Lovell, Roger Clark’s grandson. William Johnston, a former director and family member, took over from Hall as STFC chairman.

A year later, in 2000, it was announced that all K shops would close, marking another end of an era. On some high streets, K and Clarks were practically neighbours and, more to the point, were selling almost the same kinds of footwear. This duplication clearly was absurd, involving two separate advertising campaigns, two sets of accounts and two similar shop fronts. But for K to cease trading in its own right was still a blow for a brand with such an illustrious history. Some K shops became Clarks, others were sold off, and the K Women’s shoe range was incorporated into the Clarks shops.

During 2000, the issue of whether Clarks should be floated was discussed once more. The board had held consultations a year earlier with Dresdner Kleinwort Benson, resulting in the strong advice that it was not in the best interests of the company to float. It was thought that stock market conditions weren’t right and that the company would not command its true value. This recommendation was duly passed on to the shareholder council, which had already agreed that in the event of the board opting to float the council would vote on it. No such ballot was required – and as of 2012 the flotation issue has not been aired again.

Parker produced another of his strategy documents in 2000, this time for general circulation among the workforce. Although it was called ‘The Road Ahead’, much of it concentrated on the changes that had already been made both culturally and commercially. It stressed how 75 per cent of the 38.6 million pairs of Clarks shoes sold each year were now sourced rather than manufactured by the company, and he predicted that turnover would reach £1.1 billion by 2004, with profits in excess of £100 million. In fact, this landmark wasn’t achieved until 2010.

‘The key in the long term is product,’ he said. And he continued:

The shoes that we create for our customers are what will make or break our business … globalisation is the force that shapes the shoe industry and we must make the transition from what is essentially still a British company, to a global business … in order to succeed we must search relentlessly for the best creative and technical skills around the world … change is not just part of life these days. Change is life.

Results for 2001 were particularly heartening – a fourth consecutive year of record returns. Even Ravel, which had been flat for those four years, increased sales by 6 per cent, against an industry average of 1.5 per cent. Overseas, Clarks saw a drop in business in the USA following the 11 September terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center, but still saw operating profits for the year as a whole rise 31 per cent to $30 million.

Much of this success was down to more than £5 million spent on advertising. In addition, a new range for crawling babies performed well, and so too did Clarks winter boots on the back of a return to fashion for footwear of this style. A particularly strong poster ad targeted the young and the young at heart, with the copy saying: ‘Feel like an adrenalin charged finely tuned trained to the max pumped up top level athlete. On his day off.’

Towards the end of 2001, Parker gave an interview to the Daily Telegraph during which he reflected on some of the changes he had introduced:

One of the things I don’t like is people feeling they are entering an institution [in Street headquarters] … When I turned up here, everyone was in cubbyholes, and we’ve pulled down the partitions. Some people don’t like open-plan, but you can never please everyone.

Asked about Clarks’ growing international reach, he said,

Half a million people in Hong Kong buy a pair of Clarks – that’s one in ten. And we make 25 per cent of our sales in America, where they call it ‘Euro comfort’. Apart from Reebok and Nike we are the biggest shoe brand in the world.

The interviewer noticed Parker was wearing a pair of Clarks Desert Boot Originals, the famous range that had reinvented itself over and over again. Then came a question about his future, especially since it was now unlikely there would be a public flotation.

‘Aren’t you bored?’ he was asked.

‘When I was young I thought a great objective would be to retire early,’ replied Parker, ‘but the question is: retire to what? Who wants a husband at home?’

Parker didn’t retire, but when it became clear that Clarks was indeed not going to float – not now and not even sometime in the near future – he took himself off in August 2002 to join Kwik-Fit, which three years later he sold to a private equity firm, PAI Partners, for £800 million. He subsequently ran the Automobile Association and oversaw its merger with Saga. At the time of writing he is chief executive of Samsonite, the luggage company, after a brief three-month stint in 2008 working as a deputy to the London mayor, Boris Johnson.

He is quoted in the Harvard case study saying:

There are points in a business career when you go in to work in the morning, and it’s all fresh and you’re really getting traction. If you have strong esprit de corps on the team, you’re having fun, everybody’s making a bit more money and it’s a positive vibe. Post-restructuring, those early days are exhilarating because you can see things really taking off. And of course they can’t stay that way for ever. In shoes, you’re only as good as your last season. I tend to get a bit bored, and that’s not good for anyone.

Parker was replaced by Peter Bolliger. This amounted to a ‘handing over of the keys’, as Bolliger puts it, because he and Parker had worked closely to forge a powerful partnership. The only other serious candidate to succeed Parker was Bob Infantino, but he ruled himself out and remained in charge of CCNA.

Building on Parker’s achievements, Bolliger concentrated on developing Clarks as a global brand rather than, as he describes it, overseeing a ‘collection of shoes’. Under Bolliger, the company finally completed the transition from being a manufacturing company to being a wholesale and retail branded business, sourcing its shoes from abroad. He set the goal of doubling the business in the USA and substantially strengthening the workforce in the Far East, where by now some 30 million pairs of shoes were made a year, primarily in China and Vietnam. In his first annual report, for the year ending 31 January 2003, he was able to tell shareholders that operating profits in North America were up just over 40 per cent on the previous year. This trend continued during 2003, with Clarks going through the 10 million pairs a year sales barrier in North America for the first time.

The business in North America was primarily a wholesale operation, but there were now 143 Clark-owned stores. Sales of Bostonian ‘dress shoes’ had slowed – in keeping with a trend away from formal footwear in the USA – but there was excitement and anticipation about the launch of two new brands developed jointly by CCNA and the Clarks design team in Street. Privo was a range of men’s and women’s sporty casuals, and Indigo was a collection of contemporary ladies’ fashion shoes. Both were aimed at filling a gap between formal shoes at one end of the spectrum and trainers at the other. Privo was targeted at the unisex athletic and leisure markets, while Indigo was seeking to attract young, stylish American women. These two sub-brands exceeded expectation in their first full year of trading, with combined sales of more than half a million pairs.

Closer to home, Bolliger – with the full support of the board and the shareholder council – moved to close the Elefanten children’s shoe business that was based in Germany. Clarks had bought this firm in February 2001 for £23 million, making it the first acquisition that the company had made for 20 years. Elefanten was the leading children’s shoe brand in Germany, with a strong reach in both the Benelux countries and in the USA. In 2000, it recorded sales of just under £56 million, but with a profit of only £600,000. At the time, Tim Parker justified the takeover by saying the Elefanten brand had ‘exciting prospects for growth’, but he also conceded that some people might find the acquisition ‘surprising’. He said the alternative – pushing the Clarks name in Germany – was not feasible: it ‘would take a long time and considerable expenditure to convince mothers of young children [in Germany] to try a new brand, even Clarks’. Elefanten would provide the ‘critical mass immediately on which to build an exciting business in the future’. This did not prove to be the case, however, and Elefanten ceased trading in the autumn of 2004.

In the UK, planning for the new Westway Distribution Centre, next to the Bullmead Warehouse site in Street, followed Bolliger’s appointment. This extraordinary £50 million building would be fully functional within three years of its ground-breaking, capable of receiving and shipping some one million pairs of shoes a week and with capacity to stock five million pairs at any one time. There was some resistance to the building from people living near it and because of related traffic issues, but the employment it offered was welcomed locally.

For those not used to seeing a 21st-century warehouse where computerised cranes fetch and carry stock with unfailing accuracy and astonishing speed, it’s a revelation. Containers arrive from the docks at Southampton or Felixstowe, whereupon bar codes on each box are read and the goods whisked to their allotted place before later being dispatched.

The Westway Distribution Centre, completed in 2005, is packed with state-of-the-art technology and dispatches Clarks shoes all around the world.

Knapp, an Austrian logistics company, was responsible for the equipment (stacker cranes, rollers, conveyors and a Beumer double-stack sorter), while Arup was hired as the building engineers, and the computerised warehouse management system was created by Manhattan Associates.

The Westway building has a clever aesthetic. It looks a great deal lower and leaner than it really is because of its gentle curves and metallic grey/ blue colour scheme that blends with the sky above and the busy Street bypass below. There are nearly two miles of aisles inside, but retrieving a carton from the furthest location takes less than sixty seconds, with the cranes accelerating faster than a Ferrari. Westway dispatches Clarks shoes via 600 chutes to everywhere in the world except North America, where construction is under way on an even more advanced warehouse than the one in Street.

![]()

Roger Pedder always made it clear he would step down when he reached the age of 65. This he duly did in May 2006, after twelve years as chairman.

Circumstances dictated that the man who did so much to rebuild Clarks after the travails of 1993 found himself presiding over a difficult last year as chairman. Increased competition from discount stores and supermarkets, plus the launch of new fashion outlets such as Oasis and New Look, both of which added shoes to their product list, saw Clarks’ core UK market fall by 3.8 per cent. Then, shortly after Pedder’s retirement, Ravel was closed, with some but not all of its shops taken over by Clarks.

Pedder was characteristically upbeat. ‘Look how far we have come,’ he said in his final annual report. ‘Look how we have grown and how profitable our business has become. The platform we have and are building for the future delivers even in a bad year an operating profit of £82.4 million.’

There is no doubt that Pedder over this period oversaw a remarkable turnaround in the company’s fortunes. During his chairmanship, his team had to cope with the £80 million cost of closing factories in the UK and North America, and the £28 million cost of writing off Elefanten, partially offset by the sale of assets worth £70 million, including Clarks Village. However, annual turnover increased 40 per cent from £655 million in 1994 to £921 million in 2006, and pretax profits were up nearly three and a half times, from £20.8 million to £71.9 million.

Pedder, a member of the family by marriage, was replaced by Peter Davies, previously chief executive of Rubicon Retail Ltd and the non-executive chairman of Crew Clothing. Davies had held senior finance positions at Avis RentaCar and Grand Metropolitan before joining the Burton Group in 1986. For the first time in its history, Clarks had a non-family-member chairman in Davies, and a non-family-member chief executive in Bolliger. Not long afterwards, Charles Robertson replaced William Johnston as chairman of the shareholder council.

Bolliger’s goal of transforming Clarks into what he called a ‘genuine global brand’ coincided with the so-called ‘credit crunch’ that led to a global financial crisis. Even so, results for the year ending 31 January 2008 showed growth of more than 8 per cent, amounting to sales of just over £1 billion for the first time. Vindicating the company’s strategy to raise Clarks’ profile in Asia, sales across China, Hong Kong and Korea increased by 19.6 per cent, and Japan enjoyed substantial growth, up by 25.1 per cent. In North America, turnover reached a new record during a year when department stores and independent retailers were having a torrid time. Clarks increased its retail outlets by eleven in the USA, making a total of 221. And Privo was the star performer.

The global financial crisis that kicked off in 2007 and gathered steam in 2008 hit consumer spending hard. Nevertheless, Clarks opened a further 68 stores worldwide during 2008 and launched a new multi-channel, retail capability via its website. This new site – offering consumers a choice of direct next-day home delivery or a ‘click and collect’ option at any shop or Clarks franchise – made an encouraging start, generating £3.4 million of additional sales, a figure that would rise to £20.7 million a year later and £32.2 million in 2010.

![]()

Bolliger retired on 31 March 2010, after sixteen years with the company. During that time, Clarks had become the market leader on the High Street, with more than 400 own-brand shops. But his achievement went far beyond that. Peter Davies, Clarks chairman, told shareholders that Bolliger had ‘overseen the transfer of manufacturing operations from the UK; the transformation of our UK retail operation; the investment in the modernisation of our infrastructure and systems and the launch of the vision for Clarks to become a global brand’. Davies added something else – that Bolliger had been ‘instrumental in helping develop a strong internal candidate as his successor’.

That successor was Melissa Potter, who had joined the company as a graduate trainee in 1989 after reading English at Cardiff University. Her appointment was made following a global search using Egon Zendor, a firm of headhunters, but no outside candidates were felt to be her equal. As tradition dictated, Potter spent her first week learning to make a pair of shoes and then a year working in retail, notably in Clarks shops in Marble Arch in central London and in Kingston upon Thames. She had risen to be managing director of Clarks UK division and then of Clarks International, and had joined the board in June 2006.

A Clarks web page from the new retail website that was launched in 2008.

Potter became chief executive of C. & J. Clark Ltd in March 2010, aged 42. The following year, Clarks recorded its highest-ever results. Total sales grew 9.2 per cent to £1.28 billion, with operating profits increasing by 13.9 per cent to £110.9 million, the first time profits had ever exceeded £100 million. The North American business was especially successful, with profits jumping spectacularly by 82.7 per cent to $85 million, ‘well in excess of our best expectations and almost a third more than the previous highest result of $64.7 million recorded in the year ending January 2008,’ Potter told shareholders.

There was a change of command in North America. Bob Infantino left the company at the end of 2010 and was replaced as president of CCNA by Jim Salzano, an internal appointee. Since then, business there has continued to flourish, with Clarks selling 20 million pairs for the first time during 2011, with a record turnover of $839 million, representing a rise of more than 14 per cent over 2010. There are currently 290 stores in the USA and Canada, with a further 130 planned to open by 2016. As part of Potter’s integrated worldwide strategy, they are to be fitted out almost exactly like Clarks shops in the UK and the rest of the world.

Melissa Potter, appointed chief executive of Clarks in 2010, has worked for the company since joining as a graduate trainee in 1989.

Meanwhile, Clarks has established a joint venture in India with the Future Group, one of the country’s largest retail businesses, divided 51 per cent/49 per cent in Clarks favour. A new company was formed for this purpose, Clarks Future Footwear Ltd, based at Gurgaon, near Delhi, and there are now 20 dedicated Clarks stores in India. Clarks shoes are also sold widely in third-party shops and department stores in India.

Worldwide, Clarks sells more than 52 million pairs of shoes a year from a total of 1,156 shops – which include its wholly owned stores, concessions, factory outlets and franchises. There are some 15,000 employees, of whom 12,000 are based in the UK. In the financial year ending 31 January 2012, turnover for the whole group was nearly £1.4 billion, with operating profits of £115.8 million. The regional breakdown of turnover was £601 million in the UK, £536 million in North America, £162 million in Europe and £99 million in the rest of the world.

During 2012, Potter set about establishing Clarks as a global business with four regional divisions: the UK and Republic of Ireland; the Americas; Europe, including Russia; and Asia Pacific.

In seeking to develop a universal image for the brand, Potter says there are two crucial components. First, that some things never change – such as the ‘integral values’ of the company. And, second, that the company will thrive only by continually adapting to change.

It is certainly true that Clarks has remained remarkably aligned with the values of its Quaker foundations. Clarks talks openly about ‘caring for people’ both within and outside the company, and in 2012 launched the Clarks Code of Business Ethics, the aim of which is to highlight the company’s ethical values and principles, ensuring the highest standards of behaviour and integrity wherever Clarks has a presence and in everything that it does. To support this, an independent Speak Up service was launched at the same time, which enables employees worldwide to voice concerns about inappropriate activity in strict confidence.

In addition, and underpinning the company’s commitment to integrity, the Clarks Code of Practice sets standards for the company’s suppliers. This code requires full compliance with all local and regulatory requirements and supports the core principles of the International Labour Organization, the United Nations agency responsible for developing and overseeing international labour standards.

Charitable giving by Clarks amounts to some £500,000 each year, through a combination of cash donation and value of goods donated. The company supports a range of organisations, including UNICEF education projects funded from worn shoe returns, and Soul of Africa, which trains unemployed and unskilled women to hand-stitch footwear. Each sale of a pair of Soul of Africa shoes helps provide sustainable employment, with the profits from these sales being donated to initiatives aimed at children affected by Aids. In 2012, the company started to support projects by Miraclefeet in India, where children with clubfoot are treated without surgery, using plaster casting and bracing.

Over the years, various members of the Clark family have set up trusts, which also own shares. Together with the Clark Foundation, these support wide-ranging interests such as education, international aid, historic building repair, conservation and the empowerment of women in the developing world, particularly in the Middle East and Africa, and also support present or former employees experiencing hardship. Clarks’ First Step Programme in the USA provides six-month paid internships to people with disabilities. The scheme involves challenging work and is aimed at giving the internees confidence to find full-time employment.

True to its commitment to housing in Street, when the warehouses on the old Houndwood site became redundant on the completion of the new Westway distribution centre, the company, encouraged by family members Tom Clark, Caroline Gould and Richard Clark, who are all Street residents, and with the support of the shareholder council, developed an imaginative proposal.

The shareholders worked with Chris Pleeth of the company’s property department to commission architects Feilden Clegg Bradley to develop a layout for the site and a design for the first phase of building, which was then adhered to by the developers, Crest Nicholson. The layout aimed to improve the balance between cars and people and to provide a variety of open spaces occupying 40 per cent of the site, including public squares and boulevards.

All of the first phase houses and flats, completed in 2010, were built to EcoHomes ‘Excellent’ standard to achieve a substantial reduction in carbon emissions. A sustainable urban drainage system created a network of swales and reed beds. This both deals with surface water run-off and provides a habitat for native species. Mechanical heat recovery units were also incorporated.

Historically, these unchanging values have sat comfortably with Clarks’ ability to change, on which the company’s very survival has depended. As has been described earlier, the company has changed dramatically over the years: it is now strictly a wholesaling and retailing business, sourcing shoes mainly from China, Vietnam, Cambodia and Brazil, and it is governed in a very different way to how it was before the rejected Berisford bid in 1993.

Clarks’ track record in pioneering innovation goes back to William Clark’s introduction of machinery into the manufacturing process during the second half of the nineteenth century. Later, the company was quick to experiment with soling made from artificial materials; it exploited the idea of width-fittings to acclaimed commercial success and became universally recognised for measuring children’s feet properly; and it was quick to adopt computer technology.

A long way from hand-stitched sheepskin slippers: a resin model of a classic shoe produced by 3D printing technology direct from CAD data.

Today, true to its heritage of embracing modern technology, Clarks has added digital 3D additive prototyping to its shoemaking armoury. This technique, more widely known as 3D printing, creates a physical form direct from CAD data produced by a designer. A prototype model of a shoe can now be produced and assessed without the need for costly moulds, and in a tenth of the time taken by previous methods. And as well as allowing design ideas to be developed faster, this innovation also makes it possible to evaluate a wider range of variations within each style. Alongside this new 3D technology, Clarks has also pioneered the use of digital data to improve its service to customers by creating a fitting gauge for use on digital tablets and touchscreen devices – a whole new way for consumers to connect and interact with a familiar brand.

Any shoe business has to be adept at responding to fashion and seeking to shape it. Clarks’ record for this has been patchy over the years, at times taking a lead in determining fashions, at others trailing and appearing old-fashioned. Not so long ago, many consumers regarded Clarks as dowdy – safe, good value but still dowdy – but today those same consumers increasingly have a different view of Clarks.

Potter acknowledges as much:

It’s true that in the past we became polarised between young people and older people, rather than appealing to the 30–45 bracket. But that has changed. We are all about real fashion for real people with a sense of energy and fun about it. And the commonality between the average 65-year-old and 30-year-old is closer than ever before. Everyone wants to look stylish, whatever their age.

In Street, there are 60–70 shoe designers, who work up to two years in advance of any particular sales season. There is also a ‘Trend Department’ consisting of four people who look even further ahead at socio-economic developments on the one hand, and colour, form and texture on the other. A shoe spends 3–6 months in the product development stage before samples are made, and in any season Clarks produces some 80,000 pairs of samples.

Some sections of the media have picked up on the changing profile of Clarks customers.

‘Suddenly, the 186-year-old business [Clarks] has acquired street cred,’ announced The Times towards the end of 2011. The paper reached this conclusion by reporting that there were waiting lists for the company’s mid-calf suede boots, known as the Majorca Villa range, and that the Neeve Ella boot, a cross between a Spanish riding boot and a traditional British Wellington boot, was selling out in Clarks stores across the UK.

Clarks has been working in collaboration with Mary Portas, the so-called ‘Queen of Shops’, who first worked as a consultant to Clarks during Tim Parker’s time as chief executive. Since then, she and her agency, Yellow Door, have produced a series of magazine ad campaigns, culminating in 2011 with ‘Where our heart is: the spirit of Clarks’, featuring images set in the Somerset countryside against a backdrop of honey-coloured Georgian houses with honey-skinned young male and female models.

‘I wanted to bring the brand back to where it belonged,’ says Portas, who was commissioned in 2011 by the prime minister, David Cameron, to conduct an independent review into the state of the British high street. ‘Everyone steals heritage, but Clarks oozes it from every pore, and then when you add that to something modern and sexy you’ve really got reason to shout about it. To me, Clarks represents the best practice of British quality and comfort at a decent price.’

The ‘street cred’ reference in The Times touched on Clarks’ ongoing involvement in the music scene through its Clarks Originals association with live bands such as Little Dragon, Bo Ningen, The Rassle and Louise and the Pins. ‘Clarks Originals are of the moment. Always have been. Always will be’, reads the copy in the Clarks Original Live magazine that supports bands starting out on their quest for success.

Towards the end of 2012, a book called Clarks in Jamaica chronicled the perhaps surprising association between Clarks and the reggae scene on the Caribbean island. Written by Al Newman (aka Al Fingers), the book waxes lyrical about singers such as Dillinger, Ranking Joe, Little John, Super Cat and, more recently, Vybz Kartel, all of whom have incorporated Clarks into their music. It was the Desert Boot which began this love affair, finding favour in the late 1960s with Jamaica’s so-called ‘rude boys’. Newman quotes a Jamaican producer as saying, ‘The original gangster rude boy dem, a Clarks dem wear. And in Jamaica a rude boy him nah wear cheap ting.’

Historically Clarks has tended to have its greatest influence on fashion at the times when it has advertised most effectively and creatively. Its early showcards – often endorsed by stars of stage and screen – had a homely, comical edge to them. And its first national campaign in 1933 employed the services of the American artist Edward McKnight Kauffer, who at the time was regarded as an avant-garde figure and who quickly gained a reputation for elevating advertising to a high art.

Investment in advertising continues. The successful ‘Act your shoe size not your age’ campaign from the Tim Parker era was followed by ‘Life’s a long catwalk’ and then ‘New shoes’. More recently, ‘Stand Tall. Walk Clarks’ tapped into a younger, more fashion-conscious market. ‘Kids love the look and parents appreciate the quality that means (good) value for money,’ read the copy in an advertisement feature that ran in the Sunday Times in July 2012.

The importance of advertising is now ingrained. Similarly, the Clarks hold on the children’s market remains as strong as ever. ‘First shoes’ and ‘Back to school’ options are displayed prominently, supported by reminders that ‘little feet need the best of care,’ a consistent theme going back many decades. Much is made of a toddler’s first pair of shoes, with staff on hand to catch the moment in a photograph which is then presented in its own cardboard wallet. The back-to-school market is as important to the company as Christmas is to many other retailers. The abiding policy is still based around the idea of attracting the child to the brand as much as his or her parent. In the UK, out of a total of almost 29 million sales by Clarks, 10 million are children’s shoes.

Because Clarks has always stressed the importance of children having their feet properly measured and their shoes properly fitted, until 2012 the company did not sell any children’s shoes via its online channels (which in 2011 accounted for nearly 11 per cent of total retail sales). But the demand was there, prompting the company to offer customers the chance to buy either a Toddler Gauge (for £6) or Junior Gauge (for £8) for themselves so they could measure their children’s feet at home, order online and then choose between home delivery or collection at a store of their choice. Both gauges come with a set of guidelines, and there is an online video instruction.

Having put the design flair back into shoes, the company is now making sure they are displayed to best advantage, and so the stores themselves are changing. Over the next few years, the ‘white global format’, as it is known, is being phased out and replaced by the C7 format, which is warmer and more welcoming, with brown and green as the dominant colours. C7 takes inspiration from Clarks history, with shoes sitting on top of upturned wooden crates with ‘Street, Somerset 1825’ printed on them, and in many branches five lasts are secured to a panel above the main cash desk, with ‘Master shoemakers since 1825’ written underneath.

Well-designed shoes and well-appointed shops need good staff. Engaging with customers is central to Clarks retail and marketing imperatives. During 2012, a team of Clarks’ best and most experienced store managers travelled the country carrying out what the company calls ‘Leap Training’, designed to give shop assistants greater confidence on the sales floor.

‘The best people we have are those with strong outside interests who like to talk to customers,’ says Richard Houlton, Clarks Director of Channels, whose responsibilities include retail shops, franchise stores, the wholesale business and online sales. ‘We are trying to reinvigorate the shopping experience, which means you are properly greeted and feel that someone understands your needs. And a good sales person will always bring out a second choice for the consumer.’

Visitors to Clarks get a taste of the company’s purposeful informality, particularly if they are invited to the Cowshed café on the first floor. Office workers and department heads dress casually and conduct meetings at tables scattered about the room. Talking and listening are encouraged.

In the wider business world, the Clarks shareholder council is seen as a model for other family firms, with the Institute for Family Business (UK) habitually using the company to demonstrate proper family governance. The structure allows for longer-term thinking and balances profit reinvestment with dividend pay-outs.

‘The Clarks board has a clear understanding of what the owners want and in turn the owners leave it to professional managers to run the business,’ says Grant Gordon, director general of the Institute for Family Business. ‘Crucially, the owners are putting the interest of the business before their own liquidity and this sense of long-term responsibility is bound to trickle down throughout the workforce.’

Harriet Hall, the first chairman of the shareholder council following the failed Berisford bid, says that the three non-family chief executives of Clarks since that time have all ‘recognised that as a family we have an attachment to how the company is progressing that goes way beyond an interest in the figures’.

Explaining the relationship between family and management further, she continues:

If we were shareholders in a public company we would not get anything like the detail of information we are given. Questions about the minutiae of what is going on in Street are answered. There are times when we may get close to stepping over the line in trying to influence management, but on the whole I believe that they take this in the spirit in which it is meant – as an expression of our commitment to the future of Clarks.

Peter Davies, the Clarks chairman, regards the family council as an ‘effective bridge’ between the shareholders and the board. He says:

When I joined the company I was told that one of the strengths of Clarks was its passionate shareholders – and that one of its weaknesses was its passionate shareholders. In a company that has evolved as far as Clarks has in separating ownership from management, it would be easy for the lines to get blurred. The council is well informed on the company’s strategy and performance, and has regular opportunities to question the chairman, chief executive and finance director on any issues that concern them. In parallel, the shareholders can channel queries and concerns effectively through the council.

Clarks goes about its business in its own determined but quiet way and does not seek media exposure. Potter, with Davies’s backing, declines interviews with the financial press, and the Clark family – several of whom still live in Street – recoils from publicity. They come together once a year at the AGM to hear Potter and the board explain the latest set of figures and outline plans for the future, after which sandwiches and soft drinks are served in the former canteen at the back of the main headquarters building overlooking the Quaker burial ground.

Around 80 per cent of shareholders are family members or family trusts, including charitable trusts. The remainder are mainly employees, ex-employees and trusts associated with the company, including the Clarks Foundation. The total dividend paid for the year ending in January 2012 was £21.7 million.

![]()

The woollen slippers created from off-cuts by James Clark soon after 1828 were a clever idea. James was not content to live in the past and, crucially, he came up with something people wanted to buy. Today, the growth of the business still depends entirely on people wanting to buy Clarks shoes. Potter likens a brand to a promise. And the promise is that comfortable shoes can be stylish, and stylish shoes can be comfortable – and stylish and comfortable shoes can be bought at affordable prices. It must help that Clarks enjoys a brand awareness of which many of its competitors can only dream, and implicit in that awareness is a sense of trust, even though many consumers may know little about the company itself.

An insurance company recently carried out a survey to identify the profiles of what it called ‘Mr and Mrs Made It’. It found that they have an average of four bedrooms, off-street parking, a power shower, and they go on holiday abroad most years, often to far-flung destinations. They eat out at restaurants at least once a fortnight. And they wear Clarks shoes.

Surveys, like opinion polls, aren’t always reliable. What they conceal can be just as interesting as what they reveal – but you don’t need a survey or an opinion poll to determine that C. & J. Clark Ltd is a redoubtable British institution striding purposefully towards its 200th anniversary.