Chapter 1

Hendon, Pageantry in the Air

The precedent for military air displays began, arguably, with the RAF Hendon Air Pageant, the first being held on 3rd July 1920. The air pageant was the creation of Lord Trenchard, the first Marshal of the Royal Air Force and Chief of the Air Staff (CAS), who as controller of the then RAF Memorial Fund thought this a most imaginative and attractive way of raising funds and improving perception of the RAF by the public which in these early post-war years was being led to believe the service’s role was now little more than superfluous, or in any case that its continued existence as an independent service was difficult to justify. The minute sheet to the Secretary of State for Air from Lord Trenchard when requesting permission for the 1921 pageant, referred to the grounds for approval for the 1920 event stating that approval was based on the fact that this display was entirely analogous to Naval and Military assaults at arms, Regattas, Regimental sports and the like and was a necessary and important part of the training of the RAF. Therefore, presenting the case for the pageant became an annual event.

Apart from training being the most important, a subsidiary consideration in favour of holding the pageant was that the RAF were precluded from taking any but a very minor part indeed in the Royal Tournament owing to the total unsuitability of Olympia for any essentially Air Force display.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, what has become the air show industry of today grew, with both civil and military (predominantly RAF) air display organisers striving to introduce original and ever more spectacular demonstrations. Aerobatics, time over distance, height-and-speed judging competitions, and from the military side in particular, set battle scenes, mock dogfights, precision flour bombing or attacking a small fort were standard fare for the period. But the real test of skill of airmanship determining the discipline and co-ordination which has always been essential to display flying, and which would face the application of increasingly stringent regulations in later years, is aerobatics.

Either in formation, by pair or solo, aerobatics is today, as it was in 1920, the key aspect of display flying. With everything constantly changing (and often hair-raisingly close to the ground) while an aircraft is being put through its aerobatic paces, speed, height, attitude, engine throttle and the amount of g force acting against the aircraft’s surface, the demands on the pilot’s ability to control any aircraft under such circumstances and yet present a polished performance before an audience have never been in doubt. However, the amount of responsibility and trust in the individual pilot has changed beyond comparison over the years and most dramatically so during the last forty.

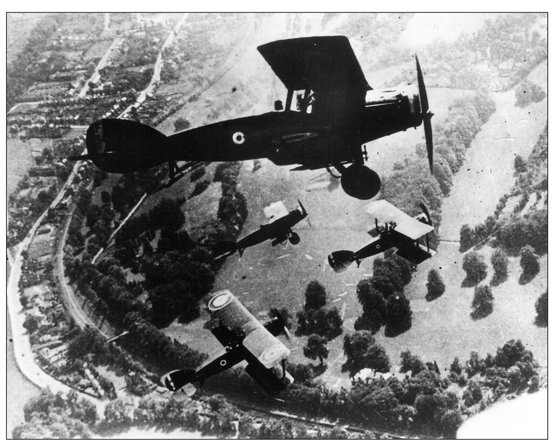

Bristol FB2s of 24 Squadron, formation rehearsal for the second Hendon Air Pageant in 1921. (Air Historical Branch)

In 1920 safety regulations were in place but were like nothing in comparison with those to come. The first Hendon pageant also bore no social resemblance to the RAF air shows of more recent years, although even more recently, corporate-style influence has gently turned the clock back a little. Tickets were sold at £2.10s for a six-seat box and 5s to park a car on the aerodrome; by comparison with the prices one would expect to pay now, this was expensive to say the least. Nevertheless 40,000 people jammed the roads leading towards the airfield. A list of dignitaries were present at this, the first official RAF air display, they included HRH Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, who watched the day’s flying from the Royal Box. Also present was Winston Churchill MP who would in years to come find immortal words to praise the endeavours of the RAF during the Battle of Britain.

The aircraft contributing to the 12-item flying programme included what was billed as ‘trick flying’ by a Royal Aircraft Factory SE5b, making its first public appearance and flown by a Flight Lieutenant Noakes, AFC, MM; a formation drill demonstration by five Bristol F2B fighters; a formation of five Sopwith Snipes and an air race by Avro 504Ks, which took off overhead the crowd line. Even for those far less constrained times, this item provoked a less than praiseworthy observation in one of the few aviation journals available at the time. The Aeroplane, if not the only, then perhaps the leading aviation journal, was reasonably impressed, commenting, ‘The most striking feature of the whole performance was the military precision with which the events were run.’

However, the magazine’s review of this first official Royal Air Force Display went on to list five separate grouses, the first of which was to helpfully suggest that the event should ‘move to Croydon as it is a more pleasant airfield and easier reached by rail and tram, and expects to have an electric railway to its gates in less than a year.’

The biggest grouse, however, if not the first in the list, was concern over ‘machines’ being allowed to take off towards the crowd. Again not unlike today’s commentators the review was at pains to ensure that it would not be misunderstood and made the point of praising ‘the wonderful RAF mechanics’. The main thrust of concern was over the likelihood of an engine failing ‘just when it was coming up to the crowd, either it would have to land in the middle of the people, or do a flat spin and crash itself.’ There was also concern in the article about the emotional effect on those watching from just a few feet below: ‘Only the uninitiated or the foolhardy are completely unmoved.’

Furthermore, concern at the wisdom of allowing a young lady parachutist, who was also described as an amateur, to participate. This referred to Miss Sylvia Boyden, who jumped from a Handley Page V/1500. The article claimed,

If a parachute drop had to be done it should have been done by a RAF officer or airman. At the Naval and Military Tournament one does not witness the sight of a young Beauteous Lady pirouetting gracefully on the fat back of a cavalry charger as it canters round Olympia.

As far as maintaining the published programme was concerned, only two items were missed, these being airships R.34 and NS.7, cause for one more grouse from The Aeroplane, which was calling the event a ‘pageant’ instead of a ‘tournament’.

Financially the pageant was successful, the money raised coming to £7,267.19s.2d, which was donated to the then RAF Memorial Fund, the forerunner of what became the RAF Benevolent Fund and is today the RAF Charitable Trust.

The following year, the event was held on Saturday, 2nd July, with the gates opening to the public at 11.00am. Again the entry prices were high, ranging from two shillings to ten shillings. Once again an impressive line-up of RAF current types was made available, this time solo aerobatics by a Sopwith Camel, formation flying by five Sopwith Snipes, nine Bristol fighters and a BAT Bantam, a rare machine. A number of set-piece items were billed, including a dogfight between five Snipes and three Handley Page V/1500s, from one of which, Miss Sylvia Boyden descended again; the destruction of a balloon followed by a dummy observer parachuting to the ground; a handycap air race involving a Vickers Vimy, Bristol Fighter and DH9a, and a relay race event, involving different RAF units equipped with thirteen aircraft each of the following types, Avro 504, Bristol Fighter and Sopwith Snipe. Each event was introduced by a trumpet call, and as many as four bands would be on parade to provide music through out the day. That year The Aeroplane reviewed the pageant again, but contented itself with just one grouse, that cars were parked at right angles to, rather than facing, the crowd line. This was fair comment as was further observed; those arriving early did so to no advantage, finding themselves stuck at the end furthermost from the action while the late-comers found themselves along the crowd line, albeit facing the wrong way.

One of the first and shortest-lived commercial ventures which the RAF made available at the 1921 and 1922 pageants was the opportunity for members of the public to purchase a jump-seat ride in the air races and formation flying. The tariff was £3.3s to fly in a multi-engined aircraft and £5.5s for a single.

Without being provoked by any tragic turn of events, the idea of allowing paying customers to participate as passengers in the flying display was discontinued from the 1923 event onwards, and can be regarded as an early indication that regulation and even the fear of possible litigation was already starting to cast a shadow in the direction of display flying. Since the end of the First World War, the RAF had encouraged and was now officially sanctioning aerobatics teams. Naturally the fighter squadrons were turned to for the provision of the services’ representative aerobatics teams. The principal display team type at the 1920 and 1921 Hendons was the Sopwith Snipe, in 1922 and 1923 it was the SE5a and it was back to Snipes again in 1924. Other display teams used the more recent front-line types of the day including the Gloster Grebe, Armstrong-Whitworth Siskin and Gloster Gamecock.

There came a break with tradition in 1927 which in a sense prophesied the future with regard to the role of the aircraft type chosen as an aerobatics team mount. The service fielded a team of five DH60 Moths. The Moth was only a light training aircraft; indeed, it was not even in regular service with the Royal Air Force, its application being as a civil trainer. I make the point that this was in some way a premonition of the future, as military display teams from the mid-1960s largely moved from using current front-line types to lighter, less awesome training aircraft. However, the choice of the de Havilland Moths powered by Armstrong-Siddeley Genet 5-cylinder radial engines for the Central Flying School (CFS) team proved to be worthwhile, much the same, one may think, of the choice in the 1960s to select aircraft such as the Folland Gnat and the Jet Provost in place of the operational Lightnings and Hunters. Through the years the annual Hendon Pageant drew many notable VIPs among its spectators, the appearance of royalty each year set a precedent that made Hendon a fashion highlight of the social calendar. King George V in 1925 was invited to give control orders over the wireless to a squadron of Grebes. A number of pilots whose names would in time become legends in RAF history were, in this era of peace across Europe, making names for themselves as aerobatics entrepreneurs at Hendon. They included Douglas Bader and Jeffrey Quill, whose name became synonymous with test-flying the Spitfire.

As the twenties gave way to the thirties a new generation of fighter aircraft were being delivered to the squadrons. Among these was the Hawker Fury, widely regarded as the finest fighter of its generation. Like the new fighters built at the turn of the 1930s it was fitted with an inline Rolls-Royce Kestrel engine and sported a nose cone to complete the bullet-shaped forward fuselage. From 1931, the Hawker Fury was the RAF’s principal interceptor and became the most prestigious aircraft to equip any of the services aerobatics teams during the 1930s. No. 43 Squadron flew a team of three Furies at the 1931 Hendon pageant, providing one of the most scintillating displays yet. It may have been the appearance of its sleek inline engine providing a bullet-like nose (state-of-the-art for 1931) or the comparative step forward in power, but either way, the Fury remained the preferred mount of RAF operational aerobatics teams, for the remainder of the Hendon pageants, at least. During this period, among the civilian-organised air pageants were the air circuses and pageants at Doncaster, the scene of one of the first air displays. The air pageants here included a night-flying display at the Doncaster race course, which included a Vickers Virginia taking off decorated with hundreds of light bulbs, as if it were an airborne adornment to the Blackpool or Las Vegas illuminations. The post-First-World-War Doncaster shows ran from 1932 until 1st July 1936.

Early Aerobatics team in about 1933. (Air Historical Branch)

In 1937 No. 1 Squadron, then the sister squadron of 43, at RAF Tangmere, was selected to field its display team of four Furies at that year’s Hendon display. The team, led by Flight Lieutenant Teddy Donaldson, flew a sequence of loops, rolls and stall turns in close formation. Later that year they took part in the international aerobatics competition at Zurich in Switzerland. The No. 1 Squadron team astonished the Swiss, French, Italians and Germans by taking to the air in dismally poor weather conditions, which forced the other teams to stay on the ground, and fly their full display sequence while the cloud base remained at 200 feet. Elsewhere overseas, at Villacoublay in France, 87 Squadron flew Gloster Gladiators, which despite their radial engines represented a step forward in performance over the Fury once again, tied, or rather connected, with rope from wingtip to wingtip. This last imaginative airborne stunt has relatively recently been reprised by the Moroccan Air Force’s premier display team, Green March, flying Cap 230s and, again, connected wingtip to wingtip.

The pageant held on 26th June 1937 marked the last of the annual Hendon pageants. The following year the Air Ministry announced, on 30th January, the end of the display, as the airfield was too small for the latest type of aircraft. Over the years since the first one in 1920, it is claimed that more than 4,000,000 spectators had visited the display and more than £150,000 had been raised for the RAF charities. The last event attracted 186,000 visitors, of which 70,000 were admitted free and 60,000 at half price. The money raised by these events appears to have been free of aircraft operating costs; certainly Treasury authority was not required for the Hendon displays as they were considered a part of the training requirement. It could also be said that Trenchard’s hoped-for generation of public support for the RAF through the air pageant had paid off, that the RAF still existed by 1937 and had not been devolved into individual arms of the other services, could be in no small part due to the annual spectacular at Hendon.

The RAF continued to organise a number of air shows in 1938 and 1939 to celebrate Empire Day. The first of these displays, the forerunners of the post-war Battle of Britain ‘At Home’ days, were held on 24th May 1934. The Empire Day displays saw the appearance of Hurricanes and Spitfires. Previously these two significant fighters had appeared in the latter couple of Hendon shows in prototype form only, but the Empire Day displays saw participation by operational aircraft. During this period, needless to say, the political situation in Europe was looking ever more bleak, and the RAF was, of course, having to turn its efforts towards more pressing concerns.

Dummy Fort being bombed during simulated air attack at Hendon in the early 1930s. (Air Historical Branch)

Hendon ‘New Types’ park circa June 1932. Note the early WWII Bomber the Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley at the left end of the enclosure and also dominating the enclosure is the prewar Handley Page Heyford. (Air Historical Branch)