Chapter 3

Battle of Britain ‘At Home’ Day

The Second World War had seen the production of some outstanding aircraft in Britain, with many great names; Spitfire, Hurricane, Mosquito, Lancaster, Halifax, Typhoon, Tempest and a number of types from across the Atlantic, which also served in the RAF; Mustang, Mitchell, Liberator, Flying Fortress, Thunderbolt and so on all represented a quantum leap in technology from the years just before the war.

The list of aircraft types is considerable; however, few of these aircraft would continue their operational service for long into the early post-war years. From the point of view of anyone who harbours the most remote enthusiasm for aviation and air displays in particular, this was very much a pity, although the war years, if nothing else, provided many young lads living in the country with a non-stop airborne extravaganza. Some of the wartime types were truly world-beaters at the quite specialised roles they had been primarily designed for.

The Hawker Typhoon, for example, was arguably the finest ground-attack aircraft of the war years, but sadly its service lasted only for that time. After the war, the numbers of Typhoons and other classic military aircraft which appeared and served during the war were quickly run down and their role was transferred to the next generation of more versatile types. The post-Second-World-War years, like the post-First-World-War years, while seeing a great reduction in number of aircraft types, on the other hand saw new changes in aircraft design and technology. The new revolutionary powerplant, the jet engine, was being developed, its potential being abundantly evident to the military mindset.

Although the Second-World-War generation of aircraft generally had comparatively short-lived operational careers, some have come to be familiar types on the post-war air-show circuit in the hands of either private collectors or specially maintained by service memorial and historic flights. Indeed, today, we are far more likely to see a Spitfire flying than more recent obsolete types, particularly in Britain, where the Civil Aviation Authority has invariably demonstrated a phobia about granting display-flying licences to even the most reliable and trustworthy private groups who have set themselves the often-unrewarding endeavour of putting retired high-performance jets back in the air before a public audience.

Saviours of the Free World, Spitfire, Hurricane and Lancaster, an early photograph of the trio together over Gaydon on 20th September 1969. (Warwickshire County)

In any case, the first public air displays to be organised by the RAF after the war took place within two weeks of the official end of hostilities in the Far East, when, as previously mentioned, 100 RAF stations opened their gates to the British public on 15th September1945 to commemorate and celebrate the victory of the Battle of Britain. Most presented flying and static displays of some current aircraft types for the visitors, as well as various other amusements and exhibits. At the time, needless to say, there were no official aerobatics teams or dedicated display pilots, but a large number of aircraft moved around the country on the day to take part in the various flying displays. In addition a large flypast, consisting of twenty-two squadrons from Fighter Command and two drawn from Coastal Command, took place over London and other parts of the country. Flypasts were mostly the order of the day at the open stations with aerobatics displays being provided, usually by the locally based units or aircraft from a nearby station. In this early period of military air displays, the British public were, not surprisingly, still war-weary, which told in the early attendance figures at some stations.

The apathy would grow before it would start to recede, and is well illustrated by the attendance at one station. RAF Finningley, an airfield the name of which would in time symbolise the RAF Air Display, attracted no more than 15,000 visitors at the 1945 ‘At Home’ Day. The following year the attendance dropped to 3,000. Even though this was a typical attendance figure for the majority of the great number of RAF units which were open to the public during the early post-war years, Finningley did not hold another Battle of Britain Display until 1960, although the participation list for the 1953 ‘At Home’ Day did have Finningley among the stations recommended by Flying Training Command to open.

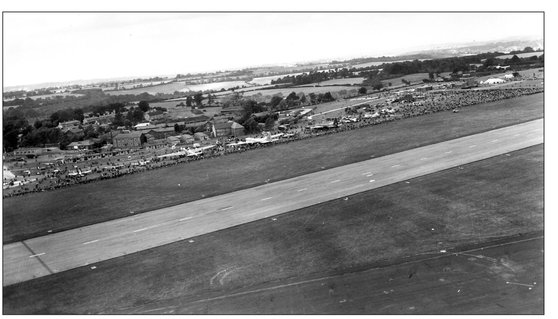

This aerial photograph shows the static and crowd line at Biggin Hill on 17th September 1955, in recent times, visitors to Biggin Hill to see the International Air Fair may note that the public area of the ground on this occasion is on the station/North side. The picture below shows the showground from within with members of the Girls Venture Corps selling programmes. (Air Historical Branch)

Nevertheless, the RAF had re-entered the arena of public display flying, and commemoration of the Battle of Britain was from virtually the outset the official focal point. This became the policy of the Air Council, the RAF’s management board, presided over by the Secretary of State for Air and including on its standing committee the Under-Secretary. In 1945 the Air Council invited a senior officer, Air Marshal Sir Richard Peck, to form a committee to review and report on the future of the service’s public commemoration of its past endeavours. Air Marshal Peck had been the Wartime Air Ministry Spokesman and from 1946 to 1949 he was Governor of the BBC. His team looked at many dates and points in the RAF’s history, including Empire Day. The revival of this, the forerunner of the ‘At Home’ Day, was supported, naturally enough, by the Air League of the Empire. Also considered was the date of the formation of the Royal Air Force, 1st April 1918, but Air Marshal Peck’s committee found that the anniversary date of the Battle of Britain, 15th September, was the most appropriate subject for public commemoration and celebration. It was officially accepted by the Air Council’s standing committee in October 1945. The report from the committee stated;

We recommend that Battle of Britain celebrations should take place during the week containing 15th September and should comprise a colour hoisting parade 15th September, RAF ‘At Homes’ on the Saturday following, or if the 15th September falls on a Saturday, on that day.

With the Air Council in agreement, it was settled then that 15th September, having become established in the public mind as the turning point of not just Britain’s but the free world’s fortunes in the war, should be adopted as the key date for annual service ceremony and public celebrations.

Still keen to secure Empire Day as the principal day for public air events, the Air League of the British Empire, in 1946, renewed their attempts to persuade the Air Council to reconsider and devote substantial resources to future events held on and around this occasion. This organisation had been instrumental in founding the forerunner of the ‘At Home’ days, Empire Day. The Air League’s recommendation was supported by the leading aviation publication of the time, The Aeroplane, which found itself again, as during the Hendon years, at odds with the Air Council. The Air Council, which now devolved the responsibility for allocating RAF assets for public display to the RAF’s Central Participation Committee, explained that owing to the heavy commitments of the RAF Commands in that year’s Victory Celebration, which was set to take place on 8th June, a date near to when Empire Day would have been staged, it was found impossible to co-operate in Empire celebrations as well and still make plans for the Victory celebrations and then prepare for Battle of Britain Week during the forthcoming September. After this the Air League, presumably accepting this point, never renewed their request for RAF participation in the revival of Empire Day.

All the same, the Air League was considered as an independent sponsor who would also take responsibility for administrative arrangements of future RAF displays. The Hendon displays had been run by a committee headed by the Air Officer Commanding in Chief (AOC in C) Fighter Command with AOCs 11 and 12 Groups as deputies and the Head of the Air Ministry’s Press and Publicity Branch with a permanent secretary, a post held by a retired Air Commodore and paid from display funds and it was the Air Ministry’s desire that future displays should be organised broadly following the Hendon precedent.

As the RAF set so much store by reaching out to the taxpayers during the early years, the Air Council initially urged all commands to open as many RAF stations as could possibly be accommodated on this one day, and that admission other than parking of private vehicles should be free. At the time this meant figures typically in the region of 80 or more stations granting free admission to the general public on one day a year, the primary aim of which was not necessarily to treat the public at every venue to a large air show but to allow a behind-the-scenes glimpse of an active RAF station. For this purpose, flying and aeroplanes were not seen as an imperative to the day’s proceedings, but to educate the punters about what the ‘local’ station did in order to contribute to the greater picture of RAF commitments and responsibilities, with flying and static displays being treated as little more than sideline attractions. It appeared to have been lost on the air chiefs, who perhaps had different priorities at the time, that Joe public was less spellbound at being invited to look round at what a ground-training school got up to, albeit with the added attraction of a small flying display, than those whose nearest RAF station was an operational airfield with plenty more in the way of interesting kit to show off, not to mention the ability to accommodate far more in the way of spectacular flying, making for a much more worthwhile day out. This particular point did increasingly concern more pragmatic thinkers before too many years rolled by.

Thanksgiving Battle of Britain service at Biggin Hill, 19th September 1954. (Air Historical Branch)

However, the main concerns, in the earlier stages, over the level of service involvement were with Operational Training Units and the disruption to their training programmes, together with a fuel shortage, noticeably in 1948, which led to calls for display flying to be as closely linked to operational flying as possible. Also the stretch of resources meant that there was heavy dependence upon the then Auxiliary flying units. At one station, North Weald, in 1950, locally based Auxilliary Squadrons, 601 and 604 and both operating Vampires, made up 10 out of 25 items on the flying programme with a further four items being provided by the resident regular Squadron, No. 72, with all units providing both formation and solo demonstrations for displays at Hendon and Hornchurch and six-ship flypasts for East Anglian ‘At Homes’. Such a level of individual unit participation would be unthinkable now. Even so, such was the strain on resources, flying displays during the 1940s were often sparse, sometimes limited to only a handful of flypasts book-ended or punctuated by an aerobatics display, hopefully provided by the likes of Fighter Command.

The entire approach, even after the experiences gained during the Hendon and Empire displays, was somewhat surprisingly misunderstanding of what exactly attracted people to an RAF station on ‘At Home’ Day, although, after the initial slump in attendance figures in 1946, a dramatic rise from a total attendance in 1947 of 129,000 to 588,000 in 1948 was sufficient evidence that the ‘At Home’ Day was a growing success, then figures dipped again during the early 1950s. Despite the obvious growing public enthusiasm, the Participation Committee was sanctioning the opening of too many units, many of which were hardly suitable for the purpose and certainly not suitable with respect to future ‘At Home’ days, a point which in due course would have to be addressed, but which was encouraged for the present due to the committee’s wish to be as comprehensive as possible in reaching out to every corner of the country so that the British people could meet their Air Force and appreciate how their taxes were being spent in this particular segment of the defence budget.

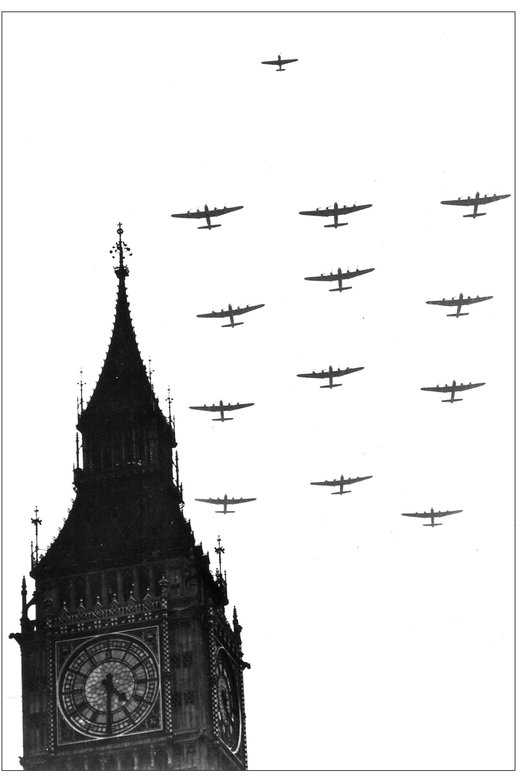

A formation flypast over London on 15th September 1951, which also fell on a Saturday that year. The formation is led by a Hurricane with this first section made up of Avro Lincolns of Bomber Command. (Air Historical Branch)

In 1948 the Participation Committee allocated RAF aircraft to take part in two air displays on the continent, and in 1949 eleven displays overseas were authorised. Also, in 1949 the very first request to make a television broadcast of one of the RAF stations on ‘At Home’ Day was made by the BBC.

The company approached the RAF regarding the televising of a 90-minute broadcast from one of the stations open on 17th September that year. For what were given as technical reasons, the BBC limited the choice to just 3 stations out of a list of 84, and all in the London area. These were; Hendon, Hornchurch and North Weald. It was proposed that the programme should consist of extracts from Battle of Britain films, interviews with Battle of Britain pilots and the ground staff in workshops, together with a comprehensive air and ground display.

The Participation Committee suggested that of the limited choice of RAF stations only North Weald would be at all suitable for the type of display required. To meet the BBC’s requirements, it was also agreed that every effort should be made to ensure that a display impressive enough, indeed, appropriate for television, should be arranged but that this should not be at the expense of the other stations. As such the Reserve Command were asked to investigate, in consultation with other commands, how far the BBC’s proposals could be met by suitable building-up of the ‘At Home’ programme at North Weald. From the arrival of ITN in 1957 it would become typical for most events to be televised by regional broadcast companies; in the meantime Biggin Hill became the station which was regularly used for television broadcasts.

A number of formative changes were brought in as policy in 1949, one such change being to the limit of detail on station plans which appeared as part of the contents of the programmes. The publication of detailed information such as station buildings and their functions was deemed undesirable on security grounds. It was agreed that in future, station plan diagrams should appear giving only sufficient information to allow the public to find their way around to those buildings open to them. Another aspect of what was probably overkill with regard to security was the banning of private cameras and other recording equipment; this policy was maintained until 1956. One station, sensitive to the security climate of the period, deliberately published in advance misleading information regarding the contents of those hangars to be opened to the public, correcting it in the programme on the day, together with an explanation for the deliberate confusion.

The standard and size of event into which the ‘At Home’ days grew, in terms of length and content of display, by the end of the 1950s, was sufficiently ambitious and substantive as to render the term ‘At Home’ somewhat misleadingly low-key, sounding for all the world like the sort of reference one would give to a village fete-style of affair.

The early Battle of Britain displays were but for some of the flying, organised locally at station-level but there was centralised organisation through the commands to the Air Council’s Central Participation Committee. The Committee would approach the commands at the start of each year and ask them to present a list of proposed stations to be open to the public. Some of the stations opening their gates to the public, as has been suggested, were wholly dependent upon participation and contributions from other nearby stations and would benefit especially where a particular rapport existed between one station and another. Otherwise co-operation on a greater scale between the various commands to which the stations reported through their groups was encouraged. The flying participants at the time continued without any reasonable level of formal training for displaying aircraft in public, and while allocation of resources was spread thin by the time it got to some stations, the proportion of RAF aircrew and aircraft engaged in formation displays and individual aerobatics on ‘At Home’ Day across the country was perhaps dangerously high. The early aerobatics teams were usually locally formed and virtually self-regulating with the ultimate sanction being the prerogative of the Station Commander, which was invariably delegated to the Officer Commanding Operations Wing. It wasn’t until 1947 that the RAF fielded its first post-war official aerobatics team, which was also the service’s first jet team, consisting of three de Havilland Vampires, led by Squadron Leader M. Lyne and drawn from the fighter wing at RAF Odiham.

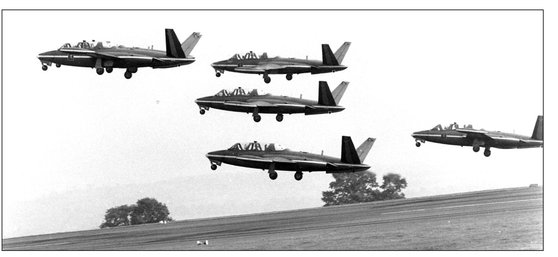

In 1948, a team of six de Havilland Vampires were drawn from No. 54 Squadron and led by Squadron Leader R.W. Oxspring. The RAF was now entering into its most prolific era in terms of aerobatics teams; forget the Hendon years, the 1950s saw RAF Fighter and Training Command aerobatics teams grow like amateur football teams. Every squadron had one, it seemed, with a solo artist or two to boot. Despite the growing proliferation of aerobatics teams throughout the RAF the majority of the items listed on any flying display remained for many years a list of types representing the various commands, carrying out formation and individual flypasts. However, with so many events on Battle of Britain Day each year to cater for, it did mean that even the most unlikely location stood a fair chance of receiving an aerobatics display by current fighter types, without which the cherry was missing from the cake.

The highlight of the day, still for some, in the early years, was a solo aerobatics sequence flown by a current fighter, which pre-1956 would be a Meteor and or a Vampire and perhaps a formation drill (not to be confused with a full aerobatics display) by such aircraft. As time passed and experience was gained, many stations would try to be imaginative and in addition to the more regular display items, would stage set-pieces and role demonstrations, which at the time would include the likes of a set scenario whereby something like a mock train would be strafed, and dive-bombed, by fighters and tactical aircraft, or if they weren’t available, training types would take on this role in such demonstrations. Indeed, if nothing else, a great deal of imagination was clearly evident in the early display years, which may have been brought about by the thinly spread resources and a desire to utilise what was available as effectively as possible. In addition to those staged at the Battle of Britain stations each September, a number of displays by the other UK-based military air arms, the Royal Navy, USAF, and the local air days staged by the Royal Air Force Association (RAFA) and various flying clubs, and events organised by the Royal Aero Club, were being held throughout the summer months. As the number of ‘At Home’ stations shrank over the years, the comprehensive standard of their flying displays and static line-ups improved as resources consequently became more abundantly available. Even so, it seems acquiring participants from anywhere has remained a constant headache for those RAF officers tasked each year with overseeing local arrangements as well as chasing the Central Participation Committee, and from 1957 the Fighter Command project team, who controlled the bulk of participating aircraft. Meanwhile, the first truly premier military and RAF air show of the post-war period came on 7th and 8th July 1950. This is dealt with in the next chapter.

Despite the obvious attraction of aircraft and flying displays, the Air Council was still keen to make the ‘At Home’ Day more of a commemorative occasion – the one official day of each year when the RAF’s supreme effort would be staged for the general public, which of course they were getting to see for free in terms of admission price. The opportunity for the greater public to get to attend any such events demanded that the number of stations ‘at home’ continue to be as widespread as possible. No doubt the still-very-rooted lifestyle of most people, for whom travel beyond a few miles was not easy, had a great deal of influence on the format of opening to the public as much as could be accommodated. The reduction of the number of stations open on Battle of Britain Saturday each year had as much to do with the increase in personal mobility as with an ever decreasing number of RAF stations and squadrons.

Also the service’s focus on demonstrating every facet of service endeavour, flying or otherwise, meant that however mundane and no matter how far removed from the principal theme of flying, the public were being asked to appreciate a behind-the-scenes look at the role of a vehicle maintenance unit equally as much as a demonstration by the most impressive aircraft of the operational commands. The result was that many stations unsuitable for holding an air display continued to be placed on the tasking list issued by the commands to the Participation Committee each year. These increasingly had to vie with operational stations, which had a head start with the locally based units, for aircraft which were being provided by other operational stations, who could be expected to be quite tribal when it came to individual station-to-station arrangements. The Participation Committee was supposed to ensure that matters were handled in such a way that there wasn’t too much of a lack in parity, but they only had a degree of control over an amount of the available resources, again the greater premium being on what could be provided by the operational commands: Bomber, Fighter, Coastal and Transport. This then had to be balanced against operational commitments and, to exacerbate the situation further, the overall size of attendance expected at one station versus another was also used to justify allocation of resources. Again the operational commands with control of large airfields with vast infrastructure, more room to accommodate and more opportunity to fill up space with ground exhibits, for which the Participation Committee and familiarity with other similar stations that weren’t open to the public, could be called upon to assist. The likes of Technical and Flying Training Commands, with little in the way of resources, represented the less spectacular end of the equation. This was especially true of Technical Training Command. Even though the Participation Committee did what they could to foster closer liaison between the commands to ensure as equal a balance of resources as possible to all stations, with so many to cater for, such was the demand on those commands with more impressive aircraft to hand, that Fighter Command in 1950 advised its Group Commanders to allocate aircraft to participate only in those ‘At Homes’ that fell within the group boundary, unless for economical reasons it was prudent to include a station inside the zone of a neighbouring Group. Vetting the list of those stations recommended by the commands, to ensure their suitability for reasons of appearance and proximity to other stations also open to the public, seems to have been loosely applied; again a desire to be not too particular when trying to reach as many taxpayers as possible may well have been a driving consideration here. The sort of stations which the Training Commands had to pick and choose between in order to be as regionally representative as possible were, as often as not, typical of the wholly inadequate variety. All the same, the 1953 ‘At Home’ was the first one to exceed 1,000,000 in public attendance throughout the UK and with the hitherto smallest number of stations open with the exception of 1951.

That year also brought, perhaps long overdue, criticism by the Commanders of the two Training Commands. In letters to the Air Council they expressed their dissatisfaction with the general policy concerning the conduct of running the ‘At Home’ days, their concerns generally being with the unsuitability of most Training Command stations for such events. Their concerns were frustrated further when at the start of 1954 requests for recommended stations for that year’s ‘At Home’ Day were received before any attempt was made to reply to the points put forward. Air Marshal Victor Groom, the Commander in Chief, Technical Training Command, again requested a response to their earlier concerns about inviting members of the public to units which did not really lend themselves to the kind of event that the Air Council looked to provide, or at least should have been looking to provide, or indeed, a letter in reply to say that their recommendations had at least been considered. The subsequent reply sent by the Deputy Chief of the Air Staff, Air Marshal Sir Thomas Pike, on 19th May 1954, was conciliatory but still held strong the belief that ‘At Home’ Day should be as much, if not more, to do with public education about the RAF as to do with entertainment;

It has always been our aim and policy to show all aspects of RAF life to the public, who, we are sure, appreciate that the less attractive or non-flying stations are an essential part of the service. Some stations of nonpermanent construction offer some of the most attractive and interesting ‘At Home’ Day programmes, and it would clearly be inadvisable not to open them simply because of the nature of their construction or function. It is therefore the intention that the maximum number of well kept and efficient stations capable of presenting interesting programmes should continue to be opened regardless of their function and construction. I would add that the approved list of stations to be opened has its origin in Commands’ own recommendations, and that careful consideration is always given to the views of Commands on whether particular stations should not open, whenever the question arises of an addition to, or a deletion from, the list.

We do, of course, fully appreciate your point concerning aircraft. While in the past we have always kept this in mind when allocating resources between Commands it has been decided that this year, and in future years, more detailed and direct control should be exercised by the Participation Committee over allocation of flying items available from other Commands. Therefore, if your representatives will attend the Committee’s annual meeting fully briefed as to the requirements of your stations, you can rest assured that every consideration will be given to your Command’s special position in this matter.

The recommendation you make about holding ‘At Homes’ on different dates during the summer has been considered by the Air Council on more than one occasion since 1945. When the dates of the Battle of Britain Week were originally decided upon; and the conclusion has invariably been that the RAF would stand to lose rather than gain from the disassociation of ‘At Home’ Day from Battle of Britain Week. The ‘At Homes’ have become a traditional part of the week’s celebrations, and the date has become widely known outside the service. Thus the number of counter attractions is kept at a minimum and, in general, September is an excellent month from this point of view as very few other important public events take place at this time.

Also, we think it would tend to confuse the public even further if ‘At Homes’ were spread over several Saturdays. The advantages to be gained from a greater spread of flying effort over a smaller number of stations would be offset by the harm which would be done to the now well-established tradition of one nation-wide day on which the public may visit their Air Force.

Moreover, there would be far less significance in merely opening a few stations on dates without any particular appeal, and there is no other anniversary comparable with Battle of Britain Week with which the ‘At Homes’ could be linked. Indeed, I would go so far as to say that Battle of Britain Week, including ‘At Home’ Day, is the envy of the other 2 services, as for once each year we definitely steal the limelight.’

Both Air Marshal Groom and the C in C Flying Training Command, Air Vice-Marshal E.B. Addison, might have been happier with tightened control over the allocation of resources. But reservations remained, in particular; ‘disruption and disorganisation of their training programme caused by the arrangements for Battle of Britain Day, particular concern being for two stations under Air Marshal Groom’s Command, Melksham and Henlow’. Further, in reply to the letter from the DCAS he requested that;

Sutton on Hull be left out because it is a small station with very little of interest to display. I consider that Cardington is not a suitable station to open because it has a very small permanent staff and the recruits there are in their first week of service, they have received no disciplinary training and are unlikely to make a favourable impression on the public. I very much hope that at the meeting of the Participation Committee you will see that I am not pressed to open these stations.

This last comment might have been prompted by more than usual concern with this being the era of National Service, meaning a considerable number of less than eager recruits in uniform. Such was the demand for ‘peacetime’ conscription to meet the demands of the Cold War and policing Britain’s remaining imperial outposts.

One aspect of the modern air displays which was an absent feature of the early ‘At Home’ days, was the participation of aircraft from foreign air arms. Initially the United States and Royal Canadian air forces were regular if not comprehensive contributors to both the Battle of Britain flypast over London and to the following open day. However, contributions from other NATO countries were until the end of the 1950s non-existent although the suggestion that continental countries should be approached was proposed initially in 1954. The idea of inviting foreign air arms to contribute to what was at the very least essentially the Royal Air Force’s one official annual public day centred purely on what was at least in the public perception the RAF’s greatest heroic endeavour of all, received very little support for and a range of reservations against it, regardless of the obvious merits. The following detailed report, at the time confidential, on proposed participation by NATO air forces in Royal Air Force ‘At Home’ Day, 1955 was issued by the chairman of the RAF Participation Committee in August 1954;

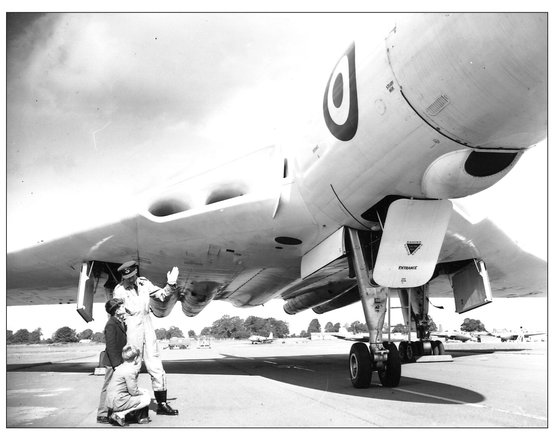

The overriding aim of the Battle of Britain “At Home” day was to invite the public to see behind the scenes of a working RAF Station. Here two school boys get close to a Vulcan and speak to one of the aircrew. This picture was taken at Gaydon on 20th September 1958; the Canberras in the background are believed to belong to one of the rare display teams of the day to have flown this type. (Air Historical Branch)

- In accordance with the Air Council’s direction, the RAF Participation Committee has examined the suggestion that other NATO Air Forces should be invited to take part on a significant scale in next year’s Battle of Britain celebrations.

- In the first place, the Committee felt bound to consider whether such an association of events was desirable in principle. The institution of RAF ‘At Home’ Day as an integral part of Battle of Britain Week followed the Air Council’s acceptance in 1945 of the report of a special Committee, under the Chairmanship of Air Marshal Peck, which was appointed ‘to consider and report on the question of a fixed date for Battle of Britain Day or any other day of RAF commemoration.’ The report of this committee says ‘We feel that the celebrations which have taken place during the past three years on the anniversary of the Battle of Britain have already linked the Royal Air Force so closely with the thanksgiving for victory in the battle, that no more appropriate date could be selected and that as the Royal Navy is indissolubly linked with Trafalgar Day, so will the Royal Air Force be linked with Battle of Britain Day’.

‘Nor do we feel that the association of AA Command, Civil Defence Services and the aircraft industry with the Royal Air Force is likely to lessen the significance of the Battle of Britain as a RAF victory.’

- The present problem, therefore, is to reconcile two entirely different ideas; on the one hand Battle of Britain Week, a national occasion, commemorating a historic battle of the past, and already a tradition of the Service, and on the other an international organisation concerned with the security of the future. The majority of the Committee feel most strongly that these two concepts are so far apart that no satisfactory compromise between them could be achieved.

- The Committee are also agreed that the association of NATO Air Force Displays with RAF ‘At Home’ Day in Battle of Britain Week would give rise to a number of difficulties. There is likely to be criticism, or at least embarrassing consequences, in the following quarters:-

- (a) The Governments of some NATO countries might find it embarrassing if their Air Forces were invited to take part in Battle of Britain celebrations.

- (i) Those who were neutral, or not actively participating in the War in 1940.

- (ii) Italy, which was then an enemy country.

The precedent might also lead to an almost impossible situation if, at some time in the future, a German Air Force were formed and included in some Western defence organisation. It would be quite impossible to invite some NATO countries and not others.

- (b) The NATO Air Forces themselves might well be reluctant to employ their star demonstration teams in an event whose original purpose is to commemorate a British wartime operation.

- (c) Some sections at least of the British public and press (particularly bereaved parents and ex-service organisations) might be expected to voice strong criticism at the introduction of an alien element into the Battle of Britain commemoration. Some criticism is already received each year at the inclusion of a USAF formation in the Battle of Britain Fly-past. These feelings would undoubtedly be inflamed by a significant participation by foreign Air Forces (and especially ex-enemy ones) into the RAF commemoration of the Battle of Britain.

- (d) Arising from (c), there may be some difficulty in securing the right type of publicity for the NATO Displays, at least without resource to expensive advertising. Also, any publicity which may be given to the NATO Displays may be expected to be at the expense of the quota of space normally devoted by the Press to ‘At Home’ Day and other annual Battle of Britain Week activities.

- (a) The Governments of some NATO countries might find it embarrassing if their Air Forces were invited to take part in Battle of Britain celebrations.

- Apart from the above considerations, the Committee feel that attention should be drawn to certain practical difficulties which are inherent in the proposal. These difficulties are dealt with in more detail in later sections of this report, but may be referred to briefly as follows:-

- (a) The question of whether Members of the Royal Family should be invited to one or more of the Displays, or are likely to be able to attend.

- (b) The many questions of protocol which will have to be decided - e.g. the allocation of participating Air Forces to individual ‘At Homes’; and the allocation of distinguished foreign guests and RAF hosts of suitable standing to the Displays.

- (c) The considerable difficulty which would be experienced, in view of the nature of normal ‘At Home’ Day arrangements, of arriving at a formula for the financial conditions which would be acceptable to all the parties concerned including RAF charities and to the Treasury.

- The Committee recognise that some practical advantages might be gained if the NATO Displays are combined with a well-established annual event, e.g. the advent of the foreign Air Forces would give an added attraction, for one year at least, to some of the ‘At Home’ flying programmes. The Committee are aware that some Station Commanders take the view that the commemoration of Battle of Britain Day may deteriorate as time goes on. They appreciate also that it would be unwise to adhere too closely to the traditions of the past if, by doing so, we were to prejudice the claims of the future. They are also impressed by the need for stimulating interest in NATO affairs by giving a public demonstration of Western solidarity. Nevertheless, after taking account of all these factors, the majority of the Committee are convinced that the balance of argument lies against the association of such a demonstration with Battle of Britain Week, and they feel it would be advisable to seek some alternative means of achieving this objective.

- Should the Air Council decide, however, that the disadvantages of the proposal should be accepted, the Participation Committee’s views and recommendations as to its implementation are set out under the following headings.

Number of Stations to be selected for NATO Displays

- 8. The Committee feel there are certain advantages to be gained by holding a NATO Display at one RAF ‘At Home’ instead of several, e.g. the organisation problems would in general be simplified: the problems of allocating visiting Air Forces and distinguished guests to different airfields without giving offence would be avoided. (These advantages could, of course, be derived equally from a single NATO theme; this could best be achieved by holding a number of displays in various parts of the country.) Multiple displays would also have the advantages:-

- (a) That the RAF should be able to put up a comparable performance to that of the visiting Air Force at each of these displays, whereas our own effort would otherwise have to compete with the best of say half-a-dozen other Air Forces.

- (b) Spreading the effort geographically might have the effect of allaying some of the criticism which might otherwise be received from within the Service that a NATO Display at one ‘At Home’ would detract from the success of all the others.

- 9. The Committee consider further that the number of NATO Displays should not be so large that having regard to the resources available, anything less than a first-class programme can be arranged at each. The ideal number would, they feel, be in the neighbourhood of six, but the exact number should preferably be decided later, in the light of:-

- (a) The experience gained from an experiment with the 1954 ‘At Home’ (see paragraph 11 below) ;

- (b) The number of foreign Air Forces which accept invitations to participate (see paragraph 10 following).

Method of allocating visiting Air Forces to Stations

- 10. It is a matter of speculation as to how many foreign Air Forces would accept invitations to participate, and consequently whether they could be allocated on a basis of, say, one or two per Station. The Committee feel, however, that the principle should be established, to avoid any diplomatic complications that allocation should be strictly on an equal basis to each of the selected Stations, and the number of Stations, should if necessary, be adjusted to achieve this end.

Method of selecting Stations for NATO Displays

- 11.In an endeavour to improve the standard of flying displays at RAF ‘At Homes’ the Participation Committee has, as an experimental measure, selected six stations which will be given preferential treatment as regards the allocation of resources for ‘At Home’ Day, 1954. These special Stations have been selected on a geographical basis, i.e. one in each of the main areas of the country, and having regard to their proximity to large centres of population.

Biggin Hill

Thornaby

Castle Bromwich

Turnhouse

St Athan

Horsham St Faith

The Committee recommend that, subject to a review of the results of this experiment, the Stations for NATO Displays in 1955 should be selected in a similar way.

Selection of main centre for Air Council Guests

- 12.While it would clearly simplify entertainment arrangements to have only one centre for guests, if it is accepted that there should be a number of displays, the Committee feel it would be contrary to the principle of equality stated above to select one of the number as a main centre. If, for instance, a Dutch Squadron were allocated to a Display other than the main centre, any distinguished Dutch guests would have to be entertained either away from their own Squadron or away from the main centre.

Organisation

- 13. The Committee consider that without difficulty the present arrangements for the organisation of RAF ‘At Homes’ could be adapted to the proposed NATO Displays, i.e. the detailed arrangements for the display programme, spectator accommodation and general administration would be exercised by the Air Ministry, by means of instructions issued through the usual channels of Command. As in the case of normal Battle of Britain Week arrangements, some central co-ordinating authority would be necessary, and it is felt that the Participation Committee itself would be in the best position to exercise this function. In addition, certain special features of the NATO Displays would have to be dealt with departmentally, e.g. the issue of invitations to the NATO Air Forces, general arrangements for their arrival and reception in the United Kingdom, invitations to distinguished guests, national publicity, etc.

Entertainment of Distinguished Guests

- 14. The Participation Committee have noted that it would be the Air Council’s intention to invite distinguished guests, but since the arrangements would depend on decisions on some of the points raised earlier in this report, and also on the Air Council’s views as to the scale which such entertainment might appropriately take, they feel unable to make any recommendations on this subject. They would, however, invite the Air Council to consider the following aspects:-

- (a) Members of the Royal Family

The King of Belgium and the Queen of the Netherlands respectively attended in person the first two NATO Air Displays held on the Continent, and precedent therefore suggests that consideration should be given to inviting Members of the Royal Family to attend NATO Air Displays in this country. The Displays in Belgium and Holland were, of course, single events, and if NATO Displays in this country were held simultaneously at six RAF stations it might be argued that no one of these would be of sufficient importance to warrant the presence of Members of the Royal Family. The following points were, however, noted by the Committee:-

- (i) The Royal Family are customarily in Scotland in September, and it cannot be expected that any Members would accept public engagements elsewhere.

- (ii) If, exceptionally, Members of the Royal Family are able to attend some of the Displays, there is the possibility of incurring complaints by visitors on the grounds that there was discrimination between Displays by the different Air Forces, e.g. a Member of the Royal Family might be watching the Dutch but not the Belgians.

- (b) Similarly it is felt that careful consideration would have to be given to an equitable allocation between Displays of distinguished guests (particularly foreign visitors) and senior RAF officers to act as hosts.

- (a) Members of the Royal Family

Finance

- 15. The financial arrangements appertaining to RAF ‘At Homes’ are governed by the Air Council’s policy laid down in 1945 that the public should be admitted free; no expenses arising from the ‘At Homes’ are admissible as charges to public funds, but the net proceeds from collections, sale of programmes, car-park charges, etc, are handed over to RAF charities. The introduction of NATO Displays into the ‘At Homes’ would mean that, according to precedent, substantial charges would arise, e.g. for the supply of fuel and oil, messing, transport, etc, for visiting Air Forces. It would be necessary to seek Treasury authority for the acceptance of these charges to public funds, and the suggestion might be made that public funds should be compensated from the proceeds of the Displays in which NATO elements take part. In such a case the amount available for distribution to RAF charities would be considerably reduced. The Committee does not feel competent to offer a definitive opinion as to the overall financial conditions for NATO Displays, but they strongly recommend, on two aspects:-

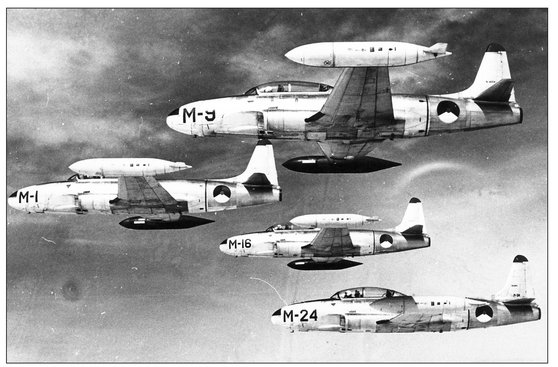

The first displays by foreign participants at RAF displays, on 15th September 1962, included this Dutch Air Force Aerobatics team, Whisky Four, which operated these Lockheed T33A Shooting Stars and displayed at Leuchars this year. In 1966, the team adopted a new colour scheme of White with Mint Green stripes and gave their final UK displays at Coltishall and Gaydon on 17th September the same year. (Sectie Luchtmachthistorie)

Theses pictures taken at Benson on 15th September 1962, show a Franch Air Force Vautour and MS760 Paris in the static line up. (Peter March)

- (a) That there should be no departure from the principle that the public should not be charged for admission to ‘At Homes’.

- (b) That the RAF charities which customarily benefit from the proceeds of ‘At Homes’ should not suffer by the diversion of all or part of these proceeds to meet the expenses arising out of the NATO Air Displays.

Initial Action

- 16. If the Air Council decide that NATO Displays are to be held in association with Battle of Britain Week 1955, the Participation Committee recommend that the following action should be taken:-

- (a) Immediate steps should be taken to notify the NATO authorities, through SHAPE, of the proposal in order that any other NATO countries who may be considering similar displays will have warning of our intentions.

- (b) At a later date, and after consultation with SHAPE invitations should be sent in the name of the RAF to the individual NATO Air Forces asking if they will participate in the Displays. (This procedure conforms with that adopted by the Belgian Air Force in 1952, when the original invitation to the RAF was sent by General Leboutte to CAS.)

- (c) Early in the new year and after reviewing the results of RAF ‘At Home’ Day, 1954, the RAF Participation Committee should initiate the necessary action for the organisation of the Displays.’

Referring to the contents of the above report at an Air Council meeting on 5th August 1954, the then Vice Chief of the Air Staff, Air Marshal Sir Ronald Ivelaw-Chapman, said he found the objections set out in the first four paragraphs of the Participation Committee’s report, with little opposition from within the council, conclusive. That the RAF would be experiencing too much turbulence to be able to put on a purely RAF display in 1955 or 1956 and that time was now too short to organise a joint NATO display for 1955 if the highest standard of planning and execution was to be achieved. His own feeling was that the era of precision flying within sight of crowds on the ground was coming to an end, because modern aircraft were too fast and were designed to operate at great heights and because modern operational techniques did not call for formation flying of the traditional kind. He would shortly be submitting a paper on that general subject. Certainly, it was becoming difficult for any Air Force, without a serious loss of training time, to stage a lengthy air display. He felt that the council should decide firmly against holding a display in 1955 or 1956, leaving for consideration the possibility of a NATO display in 1957, and should maintain their decision even if, as was not unlikely, the Supreme Allied Commander Europe suggested in the course of the next few months that the United Kingdom should act as host nation for a NATO display in 1955 or 1956. Earlier, before the report on NATO participation on ‘At Home’ Day, the VCAS stated, ‘Personally I feel that the partly political and partly psychological reasons against combining a NATO display with our Battle of Britain Week are so strong that I consider we should drop the idea altogether.’

Despite the attitude of many senior officers of the day to foreign participants outside of the United States and Canada, circumstances changed thinking again, as the RAF would forever have to cut its cloth over the next three or more decades it wouldn’t be too long before the refusal to invite foreign aircraft to participate would be reversed in order to flesh out the programmes at each station, resulting in the arrival for the first time of NATO European aircraft in the 1962 ‘At Home’ Day. As was reported that year in the aviation journal Air Pictorial, the attitude that celebrating the Battle of Britain was meant to be an exclusively National event was clearly evident. The magazine commented;

This year saw a noticeable change in the make-up of the various displays at the sixteen RAF airfields open to the public. As the RAF has been hammered by successive Ministers and Ministries over the past five years or so, its remaining units were boosted in their efforts to put on full-scale displays by a strong NATO contingent, thus destroying much of the ‘Battle of Britain’ flavour that has been so evident in the past. However, visitors from the Continental air forces all provided good fare for the enthusiast.

The premier Belgian Air Force aerobatics team, Diables Rouges seen here at Gaydon on the 20th September 1969. (Warwickshire County Records)