Chapter 4

A Good Reason for an Air Display?

F rom 1947 until 1950 the Air Council continued to be lobbied to provide an official annual Royal Air Force Display to be held mid-summer, either in addition to or in place of the Battle of Britain Week ‘At Home’. However, other commitments and the fuel shortage in 1948 were among reasons given for why such an event could not possibly be supported. That said, the RAF did provide considerable support to other major air events staged in 1947, 1948 and 1949. In 1947 a large air display organised by the Air League at Blackpool drew heavy support from the service and again in 1948 and 1949 the RAF was the most prominent contributor to the Daily Express-sponsored air show held in each of these years at Gatwick. At the start of 1950, however, the Participation Committee, at a meeting on 25th January agreed the staging of an official RAF display for that year in addition to the ‘At Home’ Day. These would be the two major events in the public display calendar that year. The airfield at Farnborough was chosen for the main display while on ‘At Home’ Day, the commands had recommended a total of 70 stations to be open. In addition, 125 branches of the Royal Air Forces Association had requested direct service support during their own events to be held during Battle of Britain Week. On top of all this, approximately 250 requests had been made to the Participation Committee from other display organisers throughout the year, these variously included country agricultural shows, civic and municipal events, athletic and sports meetings, aero club displays and events promoted by RAF Home Command in connection with recruiting. These last included Air Training Corps rallies and reserve flying schools ‘At Homes’ held outside Battle of Britain Week.

Naturally, the scale of effort in the different events was varied, and in cases where participation by aircraft or an established display team was not practicable, RAF representation was arranged from the resources of the recruiting organisation (i.e. recruiting vans, mobile classrooms, cinemas and sectioned engines). The service was also providing a range of ground displays by 1950, including gymnastics teams, RAF police dog display teams and on one occasion a display by a Bofors gun team was given, but this was not generally available, although such a display was also seen the following year.

In any event, the Participation Committee pressed ahead with the RAF’s first such event not connected with the Battle of Britain, which turned out to be the largest organised air show to date at Farnborough on 7th and 8th July 1950. Not to be confused with the now bi-annual SBAC exhibition and flying display, this event was unquestionably the most ambitious so far. It was perhaps a forerunner of the RAF Waddington International Air Show which, as such, first took place in July 1995 as a continuation/replacement event for the hitherto Battle of Britain display held annually at nearby Finningley, but with the idea of moving the event further into summer and extending it to two days, thus like the Farnborough display in 1950, marking the Waddington show out, whether intentionally or not, as the premier public event staged by the RAF each year. The RAF organised the Farnborough event and set a new standard for future military air displays. The show provided a range of ground exhibitions including; mass bands, tactical displays which included a mortar demonstration by the RAF Regiment, massed PT displays, a continuity drill, police dog displays and other service related demonstrations. The flying display was impressively comprehensive with all in-service types represented. An item on the flying programme which is not seen at present-day air shows was aerobatics ‘on request’. This involved, on this occasion, two Boulton Paul Balliol light training aircraft. A roving microphone was passed through the spectators’ enclosure, and individual members of the public were invited to test the ability of the two pilots by passing aerobatic manoeuvre requests.

The rest of the display included an aerial closed-circuit race course of 72 miles flown by Meteors, Vampires and Spitfires of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force on the 7th, and an Air Drill by R. Aux. AF Vampires and Spitfires on the 8th. Air Drill is another military flying display event which is seldom seen in the present-day display format. This is the flying equivalent of the precision movements of the parade ground, with orders being passed from the leader to the other aircraft, essentially a non-aerobatic display of precision formation flying. Solo aerobatics by each of these types were seen each day. Formation aerobatics were performed by teams of Meteors from No. 263 Squadron and Vampires of No. 54 Squadron. This team was the first of the post-war teams to trail smoke. Set-piece demonstrations included an attack on a fortified position by twelve Vampires (which fired live rockets!), and twelve Meteors scrambled to intercept incoming raids of Mosquitoes and Hornets; all this took place each day. Prototypes of future designs appeared on the flying programme as well, including the English Electric Canberra and de Havilland Venom, billed as the RAF’s new high-altitude interceptor. A well-detailed souvenir programme was published, giving a full account of what to expect from each event, the participants and the contributing units as well as a timetable. The next time the RAF sanctioned an official two-day air show was the 1995 show at Waddington.

There was, nevertheless, some continued enthusiasm for staging the official air display as an annual event especially immediately following the 1950 event. However, on 7th September 1950 the Air Council’s decision was that there would be no repeat show in 1951. The reasons being set out in the Council’s major displays policy for 1951;

The scale of effort involved in RAF participation in displays of the magnitude of the Gatwick shows, although not equal to that employed in the RAF display was considerable, and, taking into account preliminary planning and rehearsals, the effect in the critical quarter of operational training may have been quite serious. The Committee may therefore feel that while the idea of continuing the sequence of annual major displays was attractive, the RAF should not participate on a large scale in any in 1951. The customary observance (with Flypasts, ‘At Homes’ and other events) of Battle of Britain Week in September should/would, however, continue to provide widespread and beneficial publicity to the service. Considerations could be given to smaller displays (such as aero clubs etc) where RAF participation appropriately took the form of one or two items or (in a few special cases) as many as three or four (i.e. showing the Flag).

The decision was not made public at the time despite expectations in this domain. As such the Daily Express and other likely air show promoters initially made no arrangements towards the organisation of a major air display themselves in 1951. This was quite possibly due to a mistaken assumption that there would have been another large mid-summer RAF display. However, the Daily Express did sponsor the ‘50 years of Flying Exhibition & Display’, held to mark the Golden Jubilee anniversary of the Royal Aero Club on 19th, 20th and 21st July that year at Hendon, and although the RAF Benevolent Fund was one of the two beneficiaries of the proceeds from this event, which was also held on an active RAF airfield, the RAF contribution to the flying programme stretched to no more than an aerobatics display by de Havilland Vampire Mk 5s from No. 72 Squadron based at RAF North Weald. On the ground a marquee exhibition and displays by a Bofors gun drill team from No. 16 (Light Anti-Aircraft) Squadron from RAF Wattisham, a police dog display team, gymnastics team from RAF West Drayton and the Central Band of the RAF made up the bulk of the ground displays.

There is evidence, however, that there was initial enthusiasm for restaging the event in 1951 but finding a suitable airfield instantly became a problem as the Ministry of Supply was, to say the least, reluctant to acquiesce to allowing the RAF to commandeer Farnborough again, especially so near to their own SBAC display. The following letter, sent on 22nd August 1950, was the ministry’s response to a request from the Air Secretary at the time, Arthur Henderson, to stage the official RAF display at Farnborough in 1951;

My Dear Arthur,

You ask in your letter of 2nd August whether I would agree that the RAF Display should be held at Farnborough again next year.

If it were simply a matter of helping the RAF we should, of course, be only too glad to accede to your wish. But there is another side to the picture, as you evidently appreciate, namely the interference with the work of the RAE this year, on the airfield itself, the establishment lost 5 per cent of a full year’s flying time in consequence of the display. There was also an inevitable disturbance of the work of Scientists and Technicians. The total loss of research and development effort was evidently quite serious (we are trying to make a quantitative assessment of it).

The length of time it takes to develop new equipment is frequently criticised by your department. We are anxious to do everything possible to reduce it, especially with the International situation as it is at present, but the holding of the RAF display at Farnborough works in exactly the opposite direction.

I appreciate, however, that there are benefits of another kind to be secured for the RAF in holding the display.

The subject of a separate official RAF display was continually reviewed throughout the early 1950s but reasons either against it entirely or at least for putting it off until later prevailed each time.

In the meantime the annual ‘At Home’ Day continued as the RAF’s principal annual public event, combining celebration with remembrance of the battle as the main cause, with the money raised being divided between the RAFA and RAF Benevolent Fund. Throughout the early-to-mid-1950s, despite the fact that the ‘At Home’ stations were officially tasked and therefore to some degree, centrally controlled as to the number taking part, the number of events staged continued to run at an incredible figure by any comparable standards. Typically during the 1940s the number of ‘At Home’ stations would rarely be below, and were more likely to be in excess of, 80. In 1951 due to a fall in attendance figures, the number of stations was cut down to 66 but was the following year brought back up to 76 as a result of improved attendance and therefore remuneration for the principal charities. But this would be the last time that the list of open stations would be increased. On 18th September 1954, 58 RAF stations opened their gates to the public; they included 6 stations in Scotland, a region otherwise for the most part free from the air-show scene apart from the irony of the longevity of the Leuchars show, which continues as the venue for the RAF’s sole remaining Battle of Britain commemorative ‘At Home’ display. Some think this rather odd as the station is in the north-east of the country, whereas the the south-east of England was at the centre of all the action. However, that’s another story.

Despite the still-widespread number of events staged each September, from 1953 the number of events approved each year was contracting steadily. This helped the content of static and flying displays, which each year steadily improved as a result of improved organisation and co-operation as much as of the lesser demand. The difference between what to expect at the most prominent and at the most low-key event was shrinking and programmes were getting longer and more substantial. Up until and including 1954, the staple content of any flying programme continued to be dominated by Vampires and Meteors. These aircraft usually made a heavy contribution to any display at the time; other aircraft of the period from the other commands which were staple items included Lincolns and occasionally Canberras of Bomber Command, Marathons and Hastings from Transport Command and a large assortment of types from Flying Training Command including Varsities, Valettas, Balliols, Chipmunks and Harvards. When these were added together with whatever contributions from the Fleet Air Arm, USAF and RCAF could be made available, at least now sufficient resources allowed a respectable size of flying display at the majority of stations. Despite the vast number of aircraft and the number of aircrew available to fly them, the standards of discipline and qualification expected of a display pilot at the time remained rather less subject to management supervision and scrutiny when compared to more recent times, with far greater reliance and trust still being placed on the accepted skills of the individual display pilot. The situation well into the 1950s was quite alarming, as a considerable number of participating pilots were, after all, not professional display pilots and possibly may not have been afforded much time to practise any kind of display flying sequence in time for an event, much less have it properly evaluated. That’s not to say that control of display flying was reckless, or indeed, lacking concern from the top brass, but the attrition of man and machine on that one day in September each year through the 1950s was, to comment mildly, quite jaw-dropping. As recently as 1967, a young squadron pilot was tasked with working up a solo aerobatics sequence in the English Electric Lightning as late in the year as August, with the intention of displaying before the public that month and at subsequent displays in September, including two Battle of Britain ‘At Homes’. It was perhaps with not just a little luck, and despite the weather not being at its grandest, that Flying Officer Richard Rhodes saw the remainder of the display season out without incident.

It may indeed have been assumed in earlier times and with display flying still an endeavour to be defined as a separate discipline in its own right, that sufficient experience of operational and instructional flying was essentially all that was needed. But any amount of experience of flying, military or otherwise, still means a pilot is starting more or less at square one when putting together an aerobatics sequence. He may have flown all or most of the individual manoeuvres over the years, but putting them together in a set sequence and below a given flight level within a comparatively tiny laterally restrictive space as well, takes skill and rehearsal, however carefree it all may seem. Accidents happened, during the early post-war years, unfortunately more than seldom, but were perhaps somewhat inevitable given the number of events taking place simultaneously. At one early display, a Wellington was dispensing paratroopers, when a chute got caught on the tail; attempts to rectify the situation were not successful and the crew were lost with the aircraft. The most tragic occasion (apart from the John Derry incident at Farnborough.) was the 1948 ‘At Home’ Day, when no fewer than three Mosquitoes and a Spitfire crashed during aerobatics displays at four different stations. In all cases the crew were killed, with wreckage from one Mosquito falling into the public area resulting in more fatalities including a child of three.

However, in terms of separate incidents perhaps the most prolific year was 1953, Coronation year, when four Meteors (all Mk 8s) again at three different locations, each started to fall apart in flight: two were able to land at a diversionary airfield, each having lost the leading edge of the right wing; the other two disintegrated completely with the loss of each pilot. Elsewhere, a Tiger Moth was lost and a Canberra suffered damage by falling wreckage from one of the ill-fated Meteors, and another Tiger Moth and a Valetta finished the day not exactly incident-free; all this at six locations across the country in a single day. Interestingly, one of the pilots who were killed was only 21 years of age and with an average assessment rating. A further indication of the times is given by the press reaction. National newspaper coverage the next day was very matter-of-fact and in an age when as many as ten different stories could occupy the front page of any one newspaper, the most space given to the previous day’s events was a double column down the left-hand side of the News of the World and surprisingly devoid of any sensationalism. The story also concentrated on only those incidents where fatalities had occurred and in the News of the World’s coverage the double column was shared equally with news of Neville Duke’s recent record-breaking activities in a the prototype Hawker Hunter. Elsewhere, a local paper in whose area of coverage were the stations at Binbrook and Coningsby, which saw the loss of one of the Tiger Moths and one of the fatal Meteor accidents, provided a front-page column covering the day’s events at all or most of the open stations in the region in its first following edition, but leading with a more in-depth report on the reaction of the punters to the incident-free programme of events at Scampton. This was followed by an article recording a complaint by the Superintendent of the Saxondale Hospital, which treated people with nervous diseases, that jet noise from the display held at RAF Newton, 3 miles away, had distressed the patients. The column got around to mentioning the accidents at Binbrook and Coningsby in its page 3 continuation.

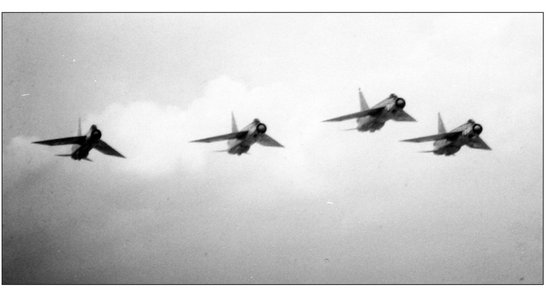

Meteor F8s of 74 Squadron, in the early 1950s, being the standard mount of Fighter Command, along with the de Havilland Vampire. (Mick Jennings)

74 Squadron Meteors seen in 1956. By this time the aircraft were camouflaged and are seen here at the top of a loop. (RAF Museum Hendon)

Such was the propensity towards accidents in the first ten years after the Second World War that it was not uncommon, during these formative years, for the CAS to congratulate his aircrew following that year’s ‘At Home’ Day on managing to keep the number of accidents to something like no more than one or perhaps two. So far have we come from those days that today’s RAF display pilot will have an above-average rating and in all probability an instructor’s rating, hence Operational Conversion Units today are, save for the odd rare exception, the usual stables from which individual display pilots and crews are sought. Once picked, usually some six months or so before the first likely public display date, pilot and crew put together an agreed and vetted display sequence on paper from a range of manoeuvres approved for the aircraft they wil be displaying. From here the sequence is practised routinely beginning at high altitude and gradually lowering the base height to the display minimum. Throughout this there is constant mentoring from the pilot and crew’s line management including a safety test flight usually carried out by an evaluation officer from the Central Flying School or from within the pilot’s own aircraft type Conversion or Evaluation Unit. From here, the budding display pilot’s Squadron Commander decides whether or not the display is worth risking before the Station Commander who in turn will decide whether or not there is any chance of embarrassment to be risked by inviting the AOC in C Group (Officer of Air Rank commanding the Operational or Training Group to which the display pilot belongs) to exercise his right of veto. It’s not unprecedented for the veto to be exercised and in times when perhaps operational commitments were fewer and funding greater, some units have fielded two competing displays with the intention of selecting only one in a fly-off. Furthermore, given the need to be constant, especially in this particular role, today’s display pilot and crew must fly the entire sequence no fewer than eight days apart. If this rule is breached, the display sequence and the crew need to be evaluated and approved again before the next public performance. This can present problems in cases where prolonged bad weather does its worst or illness intervenes; the RAF has long since stopped the practice of simply pulling another name out of the hat.

Incidents such as accidents and other more inescapable problems such as the hit-and-miss situation with the weather in September over the years gave greater credibility to those RAF station Commanders who were more in tune with the public expectations, and recommended spreading a number of station open days and air days throughout the summer. Commanders of stations regularly selected to open on Battle of Britain Day especially were in favour a changing the original post-war format, if only to get a chance of better weather or, more pressingly, stand a fair chance of attracting the top display teams. This latter point became more significant in later years when despite fewer teams to choose from, the era of the premier display team had arrived, particularly following a Battle of Britain display which had been marred by bad weather. Again as before, the suggestion was to place less emphasis on the month of September when ‘At Homes’ could be held in earlier summer months and still retain some significance with the battle.

Group Captain T.C. Gledhill, the Station Commander at Finningley in 1967, in his post-‘At Home’ Day (wash-up) report that year concentrated his comments on recommending the move of the official ‘At Home’ to a number of dates thoughout the summer. His main concerns were of course the weather, which had been particularly bad in1967 forcing the cancellation of a considerable amount of the flying programme, including most of the more impressive items: a Bristol F2B, a display team of four English Electric Lightnings, the home-based solo Vulcan, a battle set-piece and a rare performance from a French Air Force Super Mystere B2. Once again the point was made; the public turned up to see an air display rather than to commemorate the Battle of Britain, however much emphasis was placed on that aspect, and as time went on, the public would feel less empathy with commemoration, again echoing the thoughts of those who had earlier foreseen such a time. His observations and recommendations were very much mirrored in the wash-up report by the Station Commander at RAF Acklington that same year, who was concerned about the image of the RAF being damaged by the fact that his station’s display had been allocated resources which he considered to be altogether inadequate, and all the more noticeable when the nearby Sunderland Flying Club had earlier in the summer attracted the Red Arrows to their display. As it was, the nine ‘At Home’ Day stations that year had each been allocated a comprehensive list of aircraft representing all the commands as usual. Although it must be said the number of leading aerobatics teams at the time was already very much in decline and The Red Arrows had once again been allocated to the southern region stations. Indeed, as the 1960s continued to see a draw-down in the number of Battle of Britain displays, the number of Station Commanders seeking approval to arrange their own open days through the summer was on the increase as were the number allowed to pick their own date in the calendar. The station air days, one or two of which became standing annual events themselves, while not receiving the same priority status, did always receive substantial support from the RAF’s Participation Committee. However, the priority of participating aircraft allocation including diplomatic assistance with securing foreign aircraft as would be more the case in later years, was clearly afforded to the remaining official ‘At Home’ stations. This, combined with the usually more comprehensive presence of RAF aircraft, enabled the annual September events, in military terms at least, to maintain their status as ‘the official events’.

A wet start to the Leuchars Battle of Britain ‘At Home’ as crowds arrive, 17th September 1966. (National Archives)

Interestingly, a report by the central participation committee in 1964 expressed concern that the diminishing resources available meant that Fighter Command Headquarters, the body responsible for organising the annual Battle of Britain displays, found that with all these events being held simultaneously, no more than about two of the usually minimum of three hours of flying could be made available to each of what was, at the time, proposed to be 12 stations the following September, which would be marking the 25th anniversary of the battle. Then, as now, the RAF were dealing with contracting resources, which it was said, were contracting faster than the number of stations listed for each at home day. The report stated three policy consideration points for 1965. The previous October, following the 1963 display season, the committee had taken note of the considerable difficulties which had arisen during 1963 in the sphere of flying participation. These were due to three main factors:

- The increasing operational demands upon a slowly shrinking force.

- Flying units tailored to their exact flying tasks, thus leaving very few spare flying hours available for participation purposes.

- The increasing number of air displays (and various other events unconnected with flying) to which the RAF was invited to appear in the flying role, and the scale of participation requested.

The Participation Committee, although fully aware that RAF participation in public functions had a favourable influence on recruiting and kept the RAF in the public eye, agreed that it would be necessary in future to be even more selective in choosing events to receive flying participation. The Committee recommended to the Air Council (as it was then called) that the RAF should continue to participate in air displays at home and abroad to an extent compatible with the overriding requirements of operations and training. This was accepted by the Air Council on 16th January 1964. The post-1964 report stated that commands had been hard put to find aircraft for the 68 events which received RAF participation during 1964 and would also almost certainly welcome a significant reduction in calls from the Participation Committee on their slender resources.

However, it was also suggested by the Committee that commands had not been unduly over-burdened with requests for participation items and that the considerations leading to the Committee’s recommendation for 1964 apply equally for 1965, the 25th anniversary of the Battle of Britain.

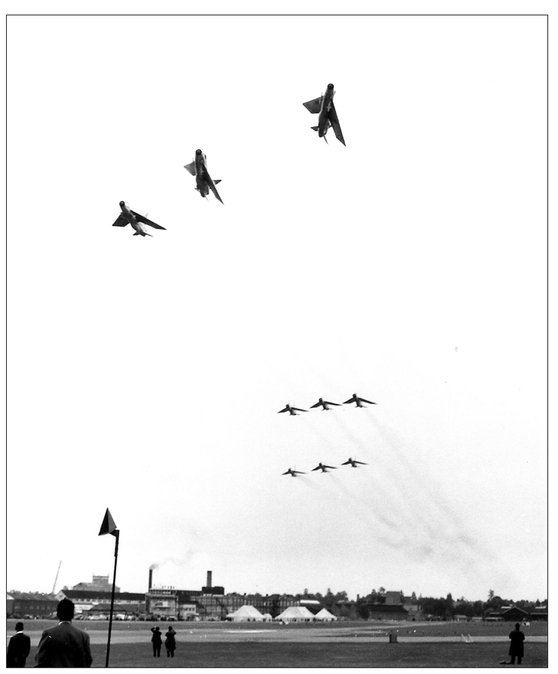

Adhoc display teams were common place at Battle of Britain displays in particular up until the 1970s. Here 23 Sqn Lightnings display over Acklington, 18th September 1965. (The National Archives)

The Lightnings seen here come from 19 Squadron and are photographed displaying over RAF Finningley on 18th September 1965. They were not an official display team but in order to spread as much flying over the various display stations on the occasion of Battle of Britain Saturday, at a time when standing aerobatics teams had been much reduced, formation air drill teams such as this were authorised just for the occasion. (John Wharam)

On future policy beyond 1965, the report suggested that 1965 may be the last year that Biggin Hill could be made available for a service-organised ‘At Home’ display. (In fact the last such event was held here on 4th September 1976.) The report further recommended a change in the future pattern, that these events should undergo a radical change but at the same time providing a vehicle whereby a good RAF image could still be projected to the public. The general feeling favoured the organising of RAF Open days at selected stations over a period, for instance, from June to September, instead of continuing to endeavour to mount major displays at a number of stations all on the same day in Battle of Britain Week.

Despite these recommendations, the report’s author, Air Commodore James Wallace, concluded:

Apart from these comments on the minutes I hope you will agree that we should do something rather more than usual for the 25th anniversary. After all our next opportunity for a ‘special’ will not occur until the 50th anniversary in 1990 and on these grounds alone I feel we should not be too worried about over-playing our hand a little. Given half a chance the other services would not hesitate for a second!

In 1952 the RAF fielded its first aerobatics team to carry a name; this was the Meteorites, who not surprisingly flew Meteors. These aircraft were Meteor T7s which were drawn from the CFS base at RAF Little Rissington and displayed a formation of three aircraft for the 1952 season only. It may not have seemed so obvious at the time, but just like the arrival of the first official Jet team in 1947, this was a less than obvious step in the direction of slowly stiffening regulation and increasing rationalisation, in other words, trying to place emphasis on one particular team with a view to that team becoming more widely identified publicly and in turn given greater official support. As the air force became leaner, fewer display teams were accommodated but the ones which remained by the end of the 1950s were carrying authorised new non-operational colour schemes and the squadron in question would forego the better part of its operational commitments for the period during which it would be on display flying duties. The idea of special colour schemes was popular among the public and media alike. The Red Arrows from early on became a household name with press visits to their base, and during the first season a documentary was made which introduced each of the pilots in the team, the problem being, especially in the early years, that there was probably an expectation that they would turn up anywhere, anytime. But more often than not, most people would have to settle for one of the other Training Command teams. Meanwhile, before The Red Arrows began their unbroken reign, operational teams were still in vogue. Through the 1950s the RAF continued to allow front-line squadrons to field their own teams with the approval of Squadron and Station commanders, but by 1961 The front-line fighter was a very different beast from 1951. In just 10 years a new generation of aircraft started to enter squadron service with the RAF and, like the previous generation, they represented a substantive step forward in technological improvement which of course also meant a substantial increase in airframe and engine performance.

74 Squadron flying their nine-strong Lightning aerobatics team at Farnborough in September 1961. (Crown Copyright)

The 1990 Red Arrows caught in the light of a descending sun over Mildenhall. (Author’s Collection)