Chapter 5

Days of Thunder

The next generation of combat aircraft starting to appear on the RAF’s inventory during the mid-fifties had much improved performance over their predecessors. The new fighters were typically 100 mph faster; these were the second-generation jets. Again the British aircraft industry was turning out classic aircraft which continued to impress. Although the United States and the Soviet Union were now developing new types and designs at a pace which eventually left Britain’s aviation industry behind. Britain’s efforts in new aircraft design were not in question, but perhaps Government support for the industry was. A catalogue of cancelled projects is probable testimony to this.

Common to the new breed of fighters and bombers was the introduction of the swept-wing concept. Aircraft such as the Hawker Hunter, Supermarine Swift and Gloster Javelin among the fighters, and the Vickers Valiant, Avro Vulcan and Handley Page Victor among the bombers would all enter service between 1953 and 1958.

All of these outstanding aircraft were at the cutting edge of their generation, as were their predecessors in their day, but the new aircraft, when they reached the public domain of the air show, would bring their own style of holding the attention of the audience. With thunderous noise and performance to match, high-performance jets would become a key ingredient of military air shows. The irony of the new breed was increasing concern or in some cases expectation that the very sophistication and high level of performance of the new-generation jet fighters and aircraft of the V Force would place them outside of the limits for display flying in sight and sound of the public. While the Meteor and Vampire continued to hold sway during the early fifties, the next generation of jets were being put through their paces at the Farnborough SBAC shows. Development types were very much sought after to appear at the RAF’s displays and when possible they were made available, though appearances were rare. The programme covers at the time usually depicted the new aircraft despite their unavailability to the majority of air displays.

The new generation of fighters and bombers started to make regular appearances at service and other displays from 1955. That year the first team of Hawker Hunters appeared courtesy of No. 54 Squadron, which fielded a team of four aircraft. In the latter part of the 1950s, solo displays by the Hunter and other new types were near enough guaranteed to appear on display programmes. The Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy also operated a number of front-line jets which were now making their way onto the flying and static line-ups at RAF displays. Among the Navy’s charges in the mid-fifties were the de Havilland Sea Venom and the Supermarine Sea Hawk, which were due for replacement by de Havilland Sea Vixens and Supermarine Scimitars (second generation) from 1957.

At about the same time as the RAF was fielding its first Hunter-equipped aerobatics teams the Royal Navy was starting to field its first jet teams, which were equipped with the earlier Sea Hawks, which from 1954 to 1956 were drawn from Nos 800 and 898 Squadrons.

In 1956, only two years into the type’s operational service, the RAF already fielded three official Hunter aerobatics teams, operating formations of four or five aircraft, which were 43 Squadron’s ‘Fighting Cocks’ led by Flight Lieutenant P Bairsto, 54 Squadron’s ‘Black Knights’ led by Captain R G Immig, a USAF exchange officer, and a hitherto unnamed team from 111 Squadron led by Squadron Leader R L Topp. A number of ad hoc teams continued to exist; however, the officially recognised teams were afforded greater latitude to work up display sequences which were often longer and more imaginative, and as a result were naturally in demand. As far as individual displays by front-line fighters and tactical aircraft were concerned, the level of commitment for the ‘At Home’ Day during this period was considerable. To ensure a comprehensive representation of the RAF’s more potent aircraft types as many as sixteen solo display pilots or crews for a single type could be allocated from within Fighter Command alone.

If there was a year which marked the start of the official Super teams, of the present-day Red Arrows style, as far as the UK was concerned, it was 1957. While a number of official and unofficial aerobatics teams proliferated throughout the 1950s, 1957 became the first year that the RAF fielded a premier aerobatics team which would represent the country. The Black Arrows of No. 111 Squadron flew an unprecedented nine Hunters. In due course this number would rise to sixteen. It would be something of a coup for any of the display stations on Battle of Britain Day to boast them on the flying programme. A number of other official Hunter teams were formed during the later part of the 1950s; these were the Group teams, one of which would be the next in line to the official Fighter Command team and was known simply as the reserve team. So, the RAF in 1958 had time for aerobatics teams league tables. Among other notable Hunter aerobatics teams were those from: No. 43 Squadron, 56 Squadron, 74 Squadron, 92 Squadron, 208 Squadron and 229 OCU.

The Black Arrows of 111 Squadron can be regarded as the RAF’s first aerobatics team run along the lines of the Red Arrows. Equipped with the Hunter F6, as the official Fighter Command team and therefore premier service display team, they reigned from 1957 to 1960 and flew a variety of display formats with varying numbers of aircraft between 5 and 16. Here the 1959 team are seen looping and rolling over Biggin Hill on 19th September. (Air Historical Branch)

The successors to the Black Arrows were the Blue Diamonds of 92 Squadron also equipped with the Hunter F6. The team flew a similar variety of display formats from 9 to as many as 18 aircraft. They were the principal Fighter Command team in 1961 and 1962 are seen here with 16 aircraft rehearsing near the Yorkshire coast and their home base Leconfield. (Crown Copyright)

The Black Arrows reigned supreme until 1960, after which the Blue Diamonds of 92 Squadron took centre stage in 1961 and 1962 expanding the team to as many as 18 aircraft for the second year. Due to the great demand for the principal teams, in order to accommodate as many of the Battle of Britain stations as possible, these larger teams would give perhaps one or two displays with their full complement, then split into two still substantial nine or five-ship aerobatics formations to display at other stations. During this time the United States Air Force European Command also operated an officially representative aerobatics team, which had first appeared in 1950, equipped with F84G Thunderjets. The American team, the Skyblazers, made their debut performance equipped with a new fighter in 1957, which they continued with until their disbandment at the end of 1961. Their new fighter, the North American F100 Super Sabre, gave the Skyblazers, the accolade of being the first aerobatics team to use a truly supersonic aircraft. Being equipped with afterburner, a facility not yet available to British fighters, their new mount gave the Skyblazers’ four-strong team an impact at air displays hitherto not seen or heard.

By now it could be argued that ‘At Home’ Day presented all the biggest and most comprehensive military air shows, certainly within Europe. For whatever reason, the time allotted for the overall flying display was not being increased in line with the increased number of participating aircraft. By the beginning of the 1960s a typical air display, generally speaking, would normally have a flying programme lasting not much more than two hours. The RAF’s ‘At Home’ Day programmes usually stretched to three hours or more, but with so many items squeezed in that the level of congestion left little time for changeover between each display. Needless to say, it was ensured that there was always something going on in the air during the three-hour period of the afternoon.

In 1957, a larger than usual representation of aircraft from the Ministry of Supply was made available to a select number of ‘At Home’ stations including a Fairey Delta FD2 assigned to give displays at Duxford and Upwood, a Boulton Paul BP Delta for Upwood, North Luffenham and Hendon, an SB5 allocated to Castle Bromwich and Hendon and a DH110 to displays at Little Rissington, Gaydon, Castle Bromwich, Cosford, Tern Hill, St Athan and Colerne. All these aircraft were provided by RAE Bedford while A & AEE Boscombe Down sent N.113s to Horsham St Faith, Honington, Duxford, Upwood, North Luffenham, Halton and Benson.

The aircraft being brought on charge were getting bigger, heavier, faster, noisier, more sophisticated, more expensive to purchase and more costly to run and commensurately, the reduction of operational RAF units notwithstanding, the number of RAF stations allocated to be ‘at home’ to the general public each year was continually reduced. Furthermore, as accidents in the earlier years were not uncommon and the blame for this attributed, it would seem, quite rightly, to the lack of expertise in the disciplines in display flying of a good many of those pilots appointed such tasks. Selection some time prior to any public displays and time given to work up a display sequence had to be approved by the Officer Commanding Operations Wing and then by the Station Commander. The same discipline was applied to the work-up of aerobatics teams. The solo display pilots were given generous latitude to work up their own display sequences; however, there was no room for debate should any reservations be held by OC Squadron over any particular manoeuvre in the sequence. This was quite lenient compared with the way things would be some 15 years hence when the AOC would sanction a single solo display of a single type. Certainly by the early 1950s there were set flying display orders and limitations for all aircraft displaying over RAF airfields which were included in both Command and Station Operation Orders. Indeed, contrary to popular belief, set rules were relaxed between the beginning of the 1950s and the early 1960s. A Fighter Command Air Staff instruction issued on 10th August 1953 stated that all aerobatic manoeuvres for both solo and formation aerobatics teams were to be completed not below 1500 ft above ground level although this limitation could be reduced on special occasions, such as the RAF display, referring to the display at Farnborough previously held in 1950, or a similar function, but only on the authority of and the extent agreed to by the AOC in C. By 1963, with regard to aerobatic manoeuvreing, the following more relaxed limitations applied:

- Manoeuvres Prohibited

- Flick manoeuvres

- Manoeuvres involving heavy loading when inverted (e.g. bunts)

- Inverted flying, other than for short periods in performing authorised aerobatics

- Crazy flying

- Spinning

- Limitations

- No formation is to fly below 500 ft AGL.

- No single aircraft is to fly below 200 ft AGL, except when demonstrating take-offs or landings.

- Aerobatic manoeuvres are not to be continued below 1,000 ft AGL.

- No aircraft which is operating at an altitude lower than 1,000 ft AGL is to fly closer than 200 yards to the public enclosure.

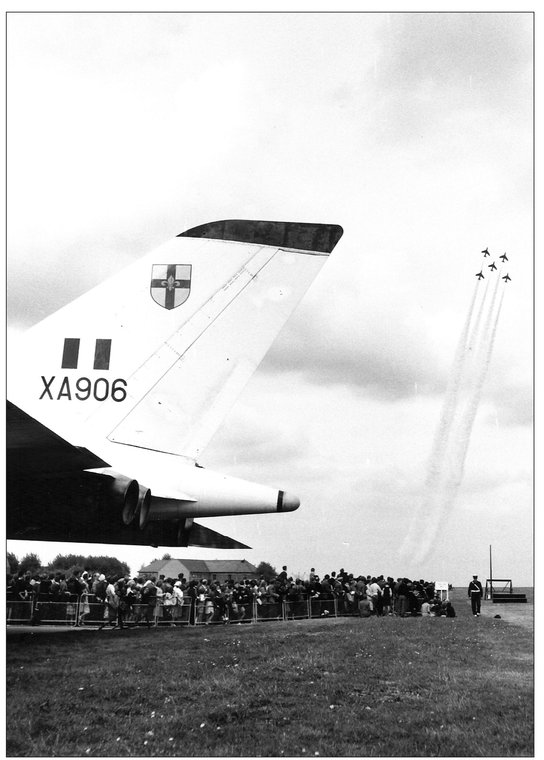

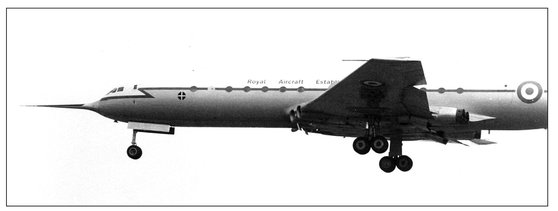

A Comet 3B, XP915 from the Royal Aircraft Establishment making an auto-land approach to Gaydon on 20th September 1969. (Warwickshire County Records)

The above restrictions may seem in some instances to be somewhat excessive even by today’s standards; however, exactly how rigidly they were applied given the apparent proximity of certain display aircraft to the public at displays over the years certainly indicates a degree of official tolerance. Nevertheless, the increase in regulation reversed the trend of ever increasing numbers of display teams and solo pilots. However, there remained a rich variety of teams within both Fighter and Flying Training Commands throughout the period of the late-fifties and early sixties. The RAF’s official aerobatics teams in 1960 numbered fifteen. There were six teams of Hunters including the legendary Black Arrows, five of Vampires, one of Meteors and at least three of Jet Provosts. All this together with a number of unofficial squadron air drill and other demonstration teams which included those operating types from other commands, such as Javelins and Canberras, provided a reasonable showcase to be drawn on.

The Red Arrows performing one of their opposition manœuvres at Abingdon on 15th September 1973. (Crown Copyright)

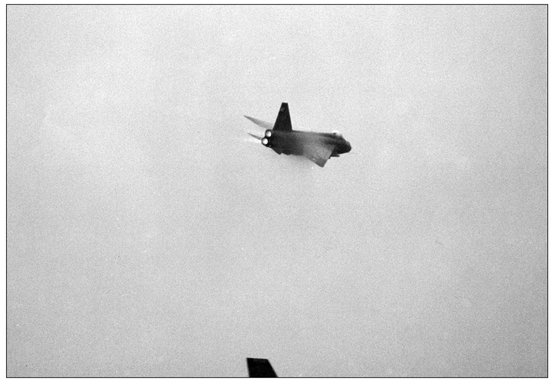

This Lightning is seen making a low high-speed run in bleak, but therefore all the more dramatic, weather conditions at Binbrook on 22nd August 1987. The event was the station’s last Air Day, held to mark the final full year of service of the type which was withdrawn from operations the following year. (Author’s Collection)

1960 was also the year which heralded the operational service of the RAF’s first truly supersonic fighter, the English Electric Lightning, an aircraft which would be in popular demand at many air shows and an almost constant participant at Battle of Britain displays throughout the next 27 years. A mean machine by any comparison, the Lightning, affectionately nicknamed the ‘Frightning’ was powered by two afterburning Rolls-Royce Avon engines and had an incomparable performance. With its 60-degree wing sweep combined with the enormous push from its twin Avon engines, this monster of a fighter would make a flying display seem incomplete for many, by its occasional absence over the next nearly three decades. In this time, contemporary front-line aircraft from foreign air forces grew in demand at displays. Formation teams of F100s, F104s and F5s from other NATO countries appeared increasingly from the mid-sixties, adding to the noise and thunder which has now become the key attraction of any predominantly military air show.

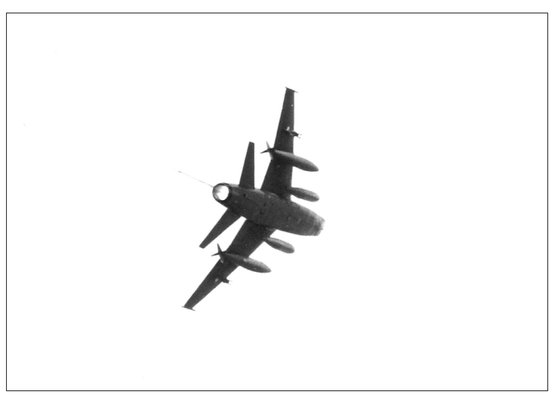

Hunter F6 of 63 squadron during simulated low level strike at Gaydon on 20th September 1969. (Warwickshire County Records)

Phantom XT872 from 892 Squadron Fleet Air Arm opening reheat over Gaydon on 20th September 1969. (Warwickshire County Press)

A rare sight by the end of the seventies, a single F100 of the Royal Danish Air Force in a reheat turn over Abingdon on 15th September 1979. (Crown Copyright)