Chapter 6

Organising the ‘At Home’

In July 1963, the Minister of Defence presented a White Paper describing the new system of defence management, whereby the old defence policy management structure was centralised, replacing the First Lord of the Admiralty and the individual Secretaries of State for War and Air with the Secretary of State for Defence, who in turn became Chairman of the new Defence Council. Under this umbrella, the Board of Admiralty, Army Council and the Air Council were now respectively replaced by the Navy Board, Army Board and the Air Force Board, each headed by a Minister of State, all under the Chairmanship of the Defence Secretary. The White Paper became effective on 1 April 1964.

The Air Force Board of the Defence Council, having replaced the Air Council, consequently took over the responsibility for allocating those RAF stations selected each year to be open to the public, with respect to commemorating the Battle of Britain. The Air Council had over the years increasingly sanctioned a smaller annual list of proposed Battle of Britain stations. Those stations proposed which clearly did not have the facilities to show off the service comprehensively, or were in such close proximity to each other that there could be no serious justification for all opening their gates, were by the end of the fifties extinct from the annual list of Battle of Britain stations. Furthermore, the Central Participation Committee, with firmer control over allocating resources from both the RAF and other military air arms, including from 1962, continental air forces, could ensure an outstanding line-up of military hardware at each display.

To closely co-ordinate and oversee planning of the movements of all the aircraft taking part in the flying displays and allocate the resources made available to which stations became the responsibility of Fighter Command from 1957. Fighter Command in turn detailed a project team each year to deal with this task and was until the end of the 1960s based at the Fighter Command Headquarters at Bentley Priory.

The more prestigious events such as the Biggin Hill BOB ‘At Home’, can expect to receive a number of V.I.P. guests. Here at the 1966 show Air Marshal Sir Augustus Walker is met on arrival by the Commandant of the aircrew selection centre Air Commodore Hugh Connolly. (The National Archives)

In any typical year during this period, planning, as for today, would start a year previous, when participating stations would receive the Air Council’s Air Force Board Instruction on station participation. This tasking list would detail the general requirements concerning what was expected to be made available and presented to the public. This would include the mandatory provisions of a static display and flying display, the minimum length of the flying display would be specified and the duration for which the airfield would be expected to remain open to the public. Six months from the day, a conference of representative officers from each of the selected stations would take place with the Central Participation Committee at the Air Ministry. The broad outline of policy would be drawn up and the basic planning of aircraft provision and touring routes made known, the responsibility for planning the touring routes and liaison with civilian air traffic was Fighter Command’s.

The local end of planning would fall to those station personnel appointed to form the local ‘At Home’ Day management committee.

The officers, NCOs and airmen appointed therefore to organise the ‘At Home’ Day at each station were doubling up; they would still have to carry out their normal operational tasks. There would be no dedicated home-based air-show staff of the kind responsible for the year-round planning of the present-day displays at Waddington and Leuchars.

The local management committee would arrange everything from liaising with Fighter Command Headquarters and making their own flying and static aircraft acquisitions to tackling all the mundane but vital requirements of the day: catering, police liaison, traffic route planning, emergency facilites, marking the crowd line and arranging car parking.

Printing the programme of events and selecting which of the station’s buildings would be made accessible to the public would also fall to the local committee. Outside the core organisation team, every other officer on the station would be tasked with overseeing everything else from accommodation for visiting air- and ground-crew down to conservation and litter-bin provision. All would be assigned responsibility for at least one or more aspects of the entire event organisation. Each station was different in how they arranged certain facilities on the ground; however, there were a number of standard provisions. Every station would typically provide at least one hangar set aside for technical exhibitions and a second hangar for refreshments, bandstand and so on. It’s the availability of infrastructure like this and the room to accommodate more inside and out that helped set RAF and often other military air shows apart from the rest as more impressive events. Usually the station cinema would be open with free admission, to show films giving an insight into service life and operations or other subject-related films. Some stations went as far as preparing a junior ranks accommodation block and the airman’s mess for public inspection. Another aspect of ground entertainment more particular to the 1950s displays was selling tickets for the opportunity to climb into the cockpit of a static fighter and fire cannon-rounds at the range butts. Also visitors could test their marksmanship skills on the station rifle range. These latter attractions seemed to disappear as the focus shifted away from providing a general picture of day-to-day military life and concentrated more on what was undeniably the main feature of the day, the flying display.

Sunset ceremony with resident pipes and drums at the close of the Leuchars Battle of Britain display, 17th September 1966. (The National Archives)

Most of the crash gates on the airfield would be open for entry and exit. As was always the case at an ‘At Home’ station, it would be the station side of the airfield which would be used as the central point of the public area, making use of the various facilities such as hangars. Until 1958, most stations printed their own glossy souvenir magazine containing the programme. From 1959 to 1962 a general publication, The Battle of Britain Souvenir Book, was printed, standard copies of which went on sale at most retail outlets across the country, but a local edition would go on sale at each of the open stations on the day, topped and tailed with relevant information for visitors including local information, station plan and Station Commander’s foreword. Quite often a provisional flying programme would be included on the back page in addition to the more up-to-date and detailed programme insert.

From 1963 onwards, a standard souvenir book was published and each respective station would have a locally produced programme insert containing all relevant information, which was provided free with the purchase of the book.

The static display and flying display, the main attractions of the ‘At Home’ Day, would be jointly arranged by both the local committee and the Central Participation Committee at the Air Ministry. Each station would depend upon its own aircraft and equipment to form the nucleus of both the static and technical displays and the flying display.

Usually each station would be able to rely upon the home-based aircraft making up to as many as four or five items on the flying programme and forming the central part of the static display. Participation by aircraft outside the station would still, as in earlier times, be acquired in some cases through local liaison, such as the nearby flying club, private owner of a vintage aircraft or through negotiation with another RAF station. The bulk, and for many stations, often the more impressive items of both the flying and static displays, would be provided by the Central Participation Committee through the FCHQ project team.

On the point of flying and static display content, the list of participants per station was very much governed by the airfield operating limits in respect of each type, and any station allocated for either static or flying, something which they had for example locally based, this was to be reported back to the Project team so resources could be sent elsewhere or indeed stood down from taking part. Of all the problems that beset most ‘At Home’ stations, especially since the first arrival of foreign participants, was providing facilities and accommodation for visiting aircraft and their crews, a task no doubt requiring an extra special effort towards decorum and hospitality if hosting the premier aerobatics team of a foreign air force. The French Air Force team Patrouille de France are notoriously particular, as many an air show organiser has found. This has come to mean, in more recent times, searching out hotels in the area. It’s been a long time since on-base messing facilities would suffice, if indeed they ever did.

Shackleton MR3 in the static line at Colerne on 19th September 1959. (Peter March)

An F100 Super Sabre sits on static at Gaydon on 17th September 1966. (Peter March)

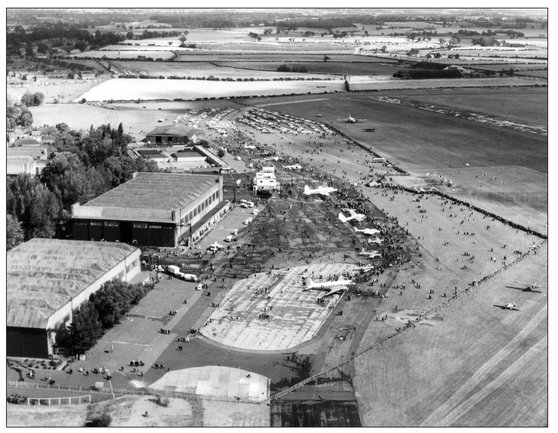

Aerial view at mid-morning at RAF Ternhill, 18th September 1965. (National Archives)

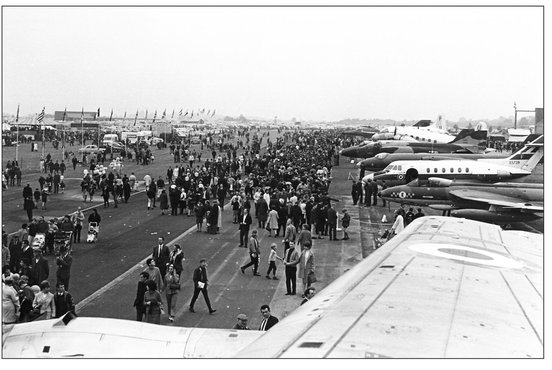

Main static park and crowd line at Biggin Hill, 17th September 1966, probably late afternoon. Note Kestrel (Prototype Harrier) in static display (The National Archives)

Not that the typical RAF Officer’s Mess has anything but first-class facilities to offer, but when, and increasingly so in more recent times, trying to find accommodation for well over a hundred additional personnel including a mix of officers and airmen from possibly six or more different countries, space to house everyone within the confines of the host base soon runs out. In recent times, the organisers of the RAF’s current premier air show at RAF Waddington have had the ability to choose the dates for holding the air show here restricted each year, in order to tie in with the availability of student accommodation at the nearby Lincoln University. The knock-on effect of this means restrictions then on the availability of participating overseas air arms, who of course will despite their willingness to take part, naturally afford the lowest priority to any overseas air show contributions. Back when the first ever International Air Tattoo was being put together, the organisers had secured the attendance of the Patrouille de France. However, matters were a little different in 1971 to the present. For a start the location of the debut IAT wasn’t Fairford, the current location, it was North Weald, just along the M11 near Epping. Unlike Fairford, a strategic deployment base for the USAF Air Combat Command, North Weald was a former wartime airfield, albeit with some structural upgrade to take early jet fighters. In the early 1960s, however, the RAF abandoned the field which became used for general aviation, the main military infrastucture remaining pretty much as it was and doubtless not too well maintained. It was in these circumstances that the French team were expected to make themselves at home. Apparently a Nissen hut was made available, but the team said they would not board their dogs in such conditions and that unless more ‘appropriate accommodation’ was found in the shortest of time, well let’s say there would have been a 30-minute gap left to fill in the flying programme.

While it was very much the case by the early 1960s that display participation was reasonably well balanced between all stations, the rule of thumb remained that priority in resource allocation go to those locations where the larger concentrations of population were. This largely explains why Biggin Hill always had priority allocation of flying display items. Furthermore, the station was the most synonymous with the Battle of Britain as well as having the whole of Greater London and the surrounding Home Counties as its catchment area, which quite often attracted a crowd of nearly 250,000. That said, owing to airfield size restrictions, the same could never be said for the allocation of static exhibits at the flagship event. Usually Biggin Hill also had a morning flying display to complement the afternoon show. Finningley, in the north, also increasingly attracted a better-than-average flying line-up, after it opened its gates to the public on 17th September 1960, and attracting an attendance of 70,000, which was larger than anticipated. The crowd doubled the following year to 140,000, becoming the typical attendance figure, and owed its success to a combination of the station’s easy accessibility, being close to a mainline rail station, and having a better catchment area (Doncaster, Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds) than most stations. This undoubtedly influenced the decision to allocate a more favourable line-up here each year and to make Finningley the representative ‘At Home’ station for the north of England in later years when the Battle of Britain displays declined.

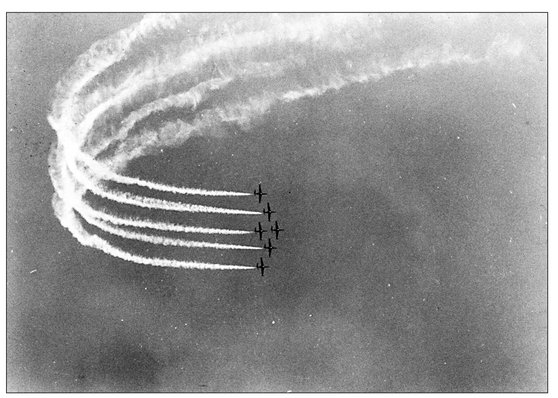

56 Squadron’s Lightning F1As, The Fire Birds during a practise session in 1963. (Crown Copyright)

Since the late fifties any mainstream air show has been able to call upon at least one jet formation team for top billing in the flying display. At the time, this invariably meant one of the various Fighter Command teams.

By the early sixties a number of foreign display teams were becoming regular items on the display circuit. On 14th September 1963, teams from the Royal Belgian Air Force, Royal Netherlands Air Force, Royal Norwegian Air Force, and the French Air Force, together with those from the RAF and Fleet Air Arm covered 15 stations across the British Isles. The allocation ensured at least one recognisable aerobatics team worthy of the description was allocated to all stations. Those stations with less assistance from the Fighter Command headquarters Battle of Britain project team were more often now those in a position to make good any gaps through self-reliance. That year Abingdon organised a lengthy set-piece tactical display involving an assortment of aircraft from Transport Command which included Hunter FGA9 close-support aircraft, Blackburn Beverley transports, Handley Page Hastings and a number of helicopters; the programme didn’t state which type, but they were probably Belvederes. Furthermore, a number of display teams made regular annual appearances at the same station; in the 1960s the Royal Navy operated a formation team of Hawker Hunters, the Rough Diamonds, which seemed to routinely find themselves a regular fixture at St Athan and St Mawgan, handy for their base at Brawdy. The Belgian Air Force supplied Leuchars with a team of two Starfighters each year through the early seventies. The Slivers weren’t a premier team, but anyone seeing their rather scary sequence of ‘opposition aerobatics’ would not have been disappointed.

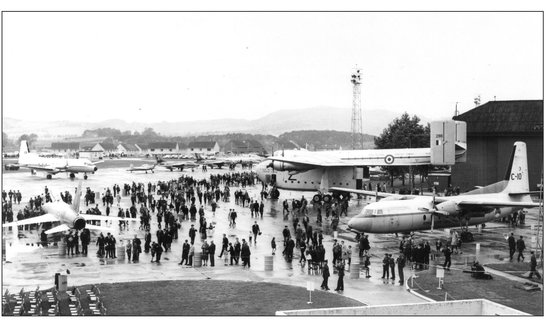

Static park and flightline mid-morning at Leuchars, 17th September 1966. (The National Archives)

The Belgian Air Force aerobatics team, Diables Rouges seen here at Gaydon on 20th September 1969. (Warwickshire County Records)

A Blackburn Beverley seen on the flightline at Colerne, 19th September 1959. (Peter March)

The number of displays that a solo or formation aerobatics pilot or crew could be allocated throughout the afternoon varied depending on the number of aircraft of the same type touring the stations, but anywhere from one to as many as three display venues would not be unusual and as many as four or more display allocations to a single aircraft. Provisional allocation in 1963 billed the last official RAF Hunter team, the ‘Black Dragons’, from 229 OCU, at no less than five displays throughout the afternoon This was most rare for an aerobatics team; the strain of precision aerobatics at low altitude, on man and machine, together with the need to land and refuel several times would normally preclude a such a heavy itinerary. As it was, the team flew their full display each at Aldergrove, Colerne, St Athan and at the home base, Chivenor, which was not open to the public but holding its own Battle of Britain memorial service that evening. Naturally with less demand on crew, aircraft and fuel consumption, those aircraft tasked to carry out flypasts would be able to take in far more stations on tour.

To confirm the routes of the participating aircraft, Fighter Command’s planning staff would consult with the Ministry of Civil Aviation. During the period 1961 to 1963 with the number of stations selected to be ‘At Home’ so far reduced to 15 or 16, the number of participating aircraft which would cover all these destinations was in the region of 750. The standard arrangement was to have three separate transit routes covering the country. The movement of aircraft around these routes was co-ordinated with the relevant air traffic agencies and where an ‘At Home’ station was situated in the vicinity of controlled airspace, dispensation would be obtained through liaison with the United Kingdom Air Traffic Services. Aircraft involved would vary in number and size, from the solo to large formation, from single-engined light trainer to heavy four-engined transport. Their role on the display circuit would vary from a full aerobatics sequence to a single flypast. A minimum separation height of 500 feet between aircraft flying under different callsigns was applied.

Departure times for touring participants would be staggered throughout the day from early morning until the latter part of the afternoon, when the last display items would make probably the third or fourth take-off that day to make the closing slot at one of the later-running flying displays. Most flying displays would finish at 5.00pm or shortly thereafter. However, depending on the size of the display some would run on later; this was more so the case in later years. In 1968 (the RAF Golden Jubilee year) Finningley’s then unprecedented five-hour flying display was billed to run until 6.30pm.

Some aircraft would be getting airborne from airfields otherwise not participating, in the morning before the display stations opened their gates and would not land again until the late evening. These would be the touring long-range aircraft, transports, maritime, long-range reconnaissance aircraft and V-bombers which would be tasked to carry out individual flypasts at several stations each along whichever route or combination thereof before returning home. Other aircraft would make their way along one route, landing to refuel between destinations. These would normally be the aerobatics teams and individual display aircraft. For all touring aircraft, punctuality was of the essence; time accuracy at the start of the run in was restricted to plus or minus one minute, and any aircraft or formation failing to meet this window had to miss their slot and continue to the next station unless they received authorisation from the relevent station’s Air Traffic Control, bearing in mind that this could cause further problems for time-on-target at the other stations on route.

The whole flying circus would therefore have to be closely monitored and guided to ensure safety to other airspace users. Indeed, many aircraft would be planned to overtake others en route to the same next airfield, which naturally required the most meticulous care in arranging slot times. Everything would for all the world take on the level of effort that would be expended if the country was going to war, as was once observed by a USAF officer when drawing comparison with the heavier controls, restrictions and much thinner programme content at the American Armed Forces days and Open Houses. (‘We have air shows, you guys go to war!’)

Bristol Britannia XM498 Hadar flying over Gaydon on 20th September 1969. (Warwickshire County Records)

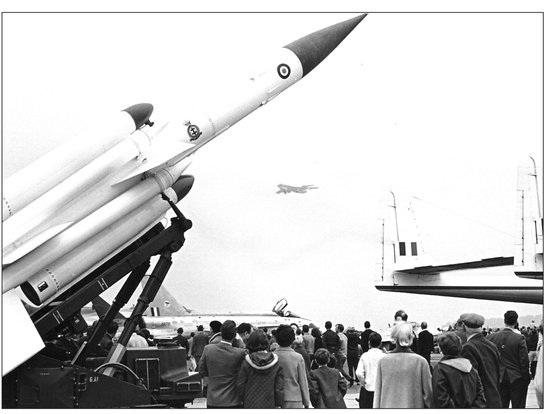

Naturally the weather has always presented the greatest uncertainty over UK air shows. Most of the events held by the RAF on 16th September 1967 had to contend with low cloud and mist as seen in these pictures from Gaydon show with this Victor disappearing in and out of the murk behind the Bloodhound missile and the scene of the static line. (Warwickshire County Records Office)