Chapter 8

Less is More?

By 1966 all of the RAF’s official display teams were provided by Training Command. The cost of maintaining front-line teams on a regular basis was now deemed to be prohibitive, largely due to the heavy fuel consumption of the immensely more powerful fighters now in service, and of course the increased maintenance cost. Furthermore, the demands on operational squadrons which hitherto had been tasked with fielding aerobatics teams made it increasingly difficult to justify the core reason for their existence when so much time and resource was expended practising close-formation aerobatics at low altitude. Other changes to the RAF display scene included the yet further decline in the number of ‘At Home’ stations appointed annually. In 1960 twenty-five stations were open and in 1974 just four stations were officially ‘At Home’ to commemorate the Battle of Britain. With a much more mobile population, fewer airfields and an increase in the number of locally organised air days during the summer, the Battle of Britain was fading from the public conscience. A move towards streamlining the RAF further began to take shape from 1967 with Transport Command being renamed Air Support Command. Next year, 1968 Bomber and Fighter Commands were gristed into one, Strike Command. Coastal was absorbed in 1969. Flying and Technical Training Commands became Training Command, also in 1968. The new structure of the Air Force naturally meant a leaner one with fewer resources to meet demands of a widespread number of air shows. Indeed, a number of hitherto front-line operational roles were reviewed. The run-down included the transfer of the strategic deterrence role to the Royal Navy which all but rendered superfluous the V-bomber force and any replacement that might have been envisaged at the time. The result of this change meant re-rolling the remaining V-bombers as follows; the tanker and strategic reconnaissance roles for the Victor, the loss of the Valiant (though this was due to the early onset of metal fatigue) and the Vulcan to continue as a tactical bomber with the standby deterrent role. The next major defence rationalisation/cut came in 1974 and 1975 when Air Support Command in particular bore the brunt of rationalisation of resources, which included the running down and closure of some of the command’s substantial infrastructure including the large bases at Colerne and Thorney Island. The result of this meant the loss from service of a range of transport aircraft. The Britannia, Comet, Belfast and the Andover, with the exception of those Andovers serving the VIP units, were all withdrawn.

Consequently the commitment to air displays by the RAF was considerably reduced, and more significantly than the cut in assets required. From now on the allocation of resources for air displays would be tailored to accommodate no more than three events on a single day, which would require only one or two representative display pilots or crews for each aircraft type. The affect of this on squadron operational diaries was, to say the least, welcomed by Commanding Officers. It’s usually the Operational Conversion Units which are called upon to provide the sole annual display aircraft, because it is believed they are best suited on the grounds that the OCU typically has more aircraft and are more given to the 9-to-5 working practice, therefore allowing some scope for a designated display pilot to practise his display sequence. In earlier times with more widespread unit involvement, at least, in the annual September list of ‘At Home’ stations, there was what can only be described as mixed feelings among those Station, Wing and Squadron Commanders who were called upon to fit such a commitment into their operational shedules, especially at a time when resources were getting comparatively much thinner and demands for operational training increased through increased NATO exercises as cohesion and operational preparedness became an increasing priority. While operational commanders no doubt accepted the principals and gains of open days and ‘At Homes’, and certainly would have been keen to honour the sacrifice of the Battle of Britain, especially as a good many of them for a good many years after the war belonged to the generation of ‘The Few’, the widespread demand on operational units each year in particular around the month of September could at times be seen as an added burden. Such remarks as were entered in respective unit operational records made it clear that the effect on operational and training syllabuses was taxing, to say the least, regarding it as somewhat remarkable when a pressing operational schedule for the month of September was fulfilled successfully. One Squadron Commander recorded his remarks in the squadron’s operational record as follows;

September is always a difficult month being the height of the ‘silly season’. Although the display flying may have reaped good publicity, it certainly did not reap valuable operational training. The flying achieved was also reduced by an abnormally high number of restrictions on flying due to weather, close proximity Royal Flights, and other factors.

The extra demanding workload placed on the ground crew rarely passed without comment also; their contribution was often commended for the mundane overtime spent preparing enough aircraft for display and spares, seemingly with little or no recognition save the CO’s references, which were nevertheless sincere. There can be no doubt that the separate demands of display flying could not be justified on too big a scale indefinitely, regardless of the public sympathy payback, and have not entirely had their passing mourned by those upon whom the business of keeping the RAF in a ready for war condition rests.

The RAF still operated a number of official display teams through the first half of the 1970s from Training Command, including four Jet Provost teams and a helicopter team in addition to The Red Arrows. The allocation of solo display aircraft became easier to manage. Again with only a couple of stations to find aircraft for at any one time, with just one or two solo display pilots/crews per type, it was possible by the end of the 1970s to ensure a full display sequence by each available aircraft type at each of the service’s main events. Much rarer by now was the single flypast in order for some type or other to manage an appearance; furthermore, and this was a real coup in terms of public expectations, everyone, whichever display they attended stood a better than even chance of seeing the service’s by-now world-leading aerobatics team, The Red Arrows.

It may come as a surprise also that while the post-war years have generally seen a continuous run-down of military infrastructure, the RAF had from 1975 to 1992 more high-performance fighter and tactical aircraft types, paraffin burners, to use colloquial reference, on its inventory than ever before or since, all of which were likely to be represented at each of the four remaining ‘At Home’ displays. In the 1960s the Lightning and Hunter were the only operational fighters that the RAF could allocate for display, albeit often presented in a variety of display formats. The less familiar Javelin was impressive enough, but no aerobatics performer compared to the other two and increasingly less available being consigned nearly exclusively to the annual Battle of Britain display circuit. From 1965 to 1968 all remaining operational squadrons were deployed overseas until the Javelin’s out-of-service date in April 1968. By the 1980s the flagship events organised by the RAF at least could expect to attract a representative solo performer from each of its now most varied front-line fighter stock. Lightning, Phantom, Harrier, Jaguar, Buccaneer and Tornado GR1 and F2 were all represented on the display circuit by at least one solo demonstrator. The last 22 years have seen a drastic change for various reasons, as is explained later. As the presence in the air at a display of any high-performance jet has always been guaranteed to bring a bored crowd to their feet, out of the beer tent and halt them on their way back to the car halfway through the flying display. It’s probably fair to say that in this respect the 1980s saw the best selection of RAF solo displays. The nadir of RAF front-line contributions to air displays generally, indeed, was probably reached during this period, save for 1985 when for reasons not entirely clear, very few individual aircraft displays were sanctioned by the RAF.

Lightning F1A, XM216 makes a fast low-level run over Gaydon on 20th September 1969. (Warwickshire County Records)

The United States Air Force, which provided the Skyblazers team until 1961, remained a constant contributor to all UK air shows with whatever was to hand, but flypasts only until the arrival of aircraft of the F15, F16 class. The USAF European Command fielded individual displays by the new operational types routinely in the pre-Ramstein tragedy era.

At the 1988 USAFE Air Day at Ramstein Air Base in Germany, the Italian Air Force’s premier aerobatics team, the Frecce Tricolori were involved, in terms of carnage, in the worst ever accident at an air show. During a particularly delicate manoeuvre unique to them, tragedy struck. The manoeuvre required two formations of four and five aircraft to fly opposing loops along the crowd line, followed by a solo to fly through the bottom of the loop towards the crowd line just before the two formations crossed at that point completing the loop. That’s where it all went wrong.

Whatever the circumstances regarding timing and calculation, it was at this point in the manoeuvre that two of the aircraft made contact with each other. The subsequent loss of control meant that a third aircraft was hit by wreckage or an out-of-control aircraft, the end result being that all three aircraft involved in the mid-air collision came down into the immediate crowd area, aviation fuel broke free and was ignited. Consequently some 67 people were incinerated instantly or died later from the most horrendous burns injuries.

This inevitably provoked a heavy-handed reaction from some countries and at least a review of display flying policy in others. The German and Danish Governments banned public display flying, although both countries have since rescinded and the Germans have changed their minds again. The Luftwaffe’s Chief of the Air Staff in 2004, a man apparently not given to air shows, particularly where military aircraft were concerned, is said to have had his mind made by an incident involving a display carried out by one of his MiG 29s, which had a narrow escape. Evidently there was a significant delay between the event and his finding out about it, and while he was prepared to allow more staid aircraft to fly at displays at home and abroad, for example the C160 Transall was allowed to continue on the display circuit, appearing at Leuchars that year, planned displays by the service’s F4 and Tornado for that year were cancelled, evidently to the disappointment by the selected display crews as much as anyone else. There has been a change of office at the head of the Luftwaffe since, but there remains no indication as yet that this air arm’s fast jets will make a comeback to the display scene. Participation by the United States Air Force in overseas flying displays sharply declined after the incident, and has never really recovered since (although this can also be explained by the withdrawal since the early 1990s of a considerable chunk of the American Armed Forces). Other countries reacted to the tragedy with a greater degree of balance and objectivity, and settled for the introduction of tighter display flying regulations, which involved the increase of the minimum safety distance, the banning of overhead display arrivals and departures (for a while dispensation was granted to certain military teams, but no more) and greater restriction on manoeuvring towards the crowd line. Furthermore, the recent cuts in the defence budget under ‘options for change’ and three subsequent reviews has also reduced the scope for presenting many display items, such as large formations, role demonstrations and set-piece scenarios.

The most significant change in the format of flying displays came towards the end of the 1970s. Then, it was possible to cram as many as 35 or more display items into three hours; in the 1990s as few as 25 items can be spread over seven hours.

Since the latter part of the 1970s, with the greater spacing of flying display timings and the much reduced number of ‘At Home’ stations meaning only one or two stations holding displays simultaneously, the organisational demand has diminished considerably, allowing a greater degree of autonomy for the respective air show office at the station end, or as it is still called at Leuchars, Battle of Britain Office. As mentioned, the introduction of greater spacing between items has also become possible, indeed, necessary due to the greater number of display items operating from the host airfield rather than touring around the country to several locations. Today time has to be allocated throughout the flying display to more aircraft movements, take-offs and landings of display aircraft together with gaps of several minutes between movements and display sequences. Lengthier periods between the end and start of flying display items came about following suggestions for improvements in successive post-display reports; one minute was an insufficient gap between the end and start of each item. However, the post-display report from Gaydon in 1960 stated that the unprecedented flying display of four hours and a start time of 13:40hrs was too long and too early for the 43 items expected and that in future a start time of 14:15 with the programme compressed into three hours would be more advantageous. At a time when several programme items were flypasts, consuming just one or two minutes, then possibly three to four hours is long enough. A number of Battle of Britain displays did try to make as much use of available daylight, extending the latter end of the schedule to in some cases as late as 18:30hrs. This in September would always mean people in cars queueing in the dark just to get to an airfield exit.

Throughout the last decade military air displays became cavalcades of fighter solo demonstrations, which typically are afforded 7 to 10 minutes per slot and with the longer gaps in between, the average flying time at such displays can easily exceed 6 hours with, if anything, fewer display items. But as observed earlier, fast jets are for most people the true crowd pullers and for many air forces, including now the RAF, fast jets make up the bulk of the front-line strength, large heavy bombers being scarce outside the USA and Russia. The imagination which provided the mix of massed formations, ad hoc operational display teams, stream take-offs, role demonstrations and set-piece scenarios seemed to become virtually non-existent in the 1990s outside of the Royal International Air Tattoo (RIAT), which has become without argument the largest military air show in Europe and arguably the largest worldwide. Because the paraffin burners are by far the biggest crowd-pullers it is alas typical that their presence on the air show circuit is at odds with the reason they exist at all. In addition they carry with them the greatest concerns from all around as regards operating costs, safety limits and still then potential for disaster. As it is, the safety record of military front-line aircraft at public events is, to say the least, most acceptable.

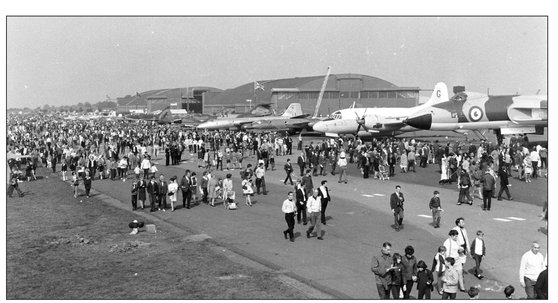

Early morning crowd building up at Gaydon along the main static display, 20th September 1969. (Warwickshire County Records Office)

Major aerobatics teams have increasingly consumed more time to fit their display sequences in. Add to this the fact that more often than not an aerobatics team will operate from the display venue. Time allocated to a premier military aerobatics team has stretched from between 12 and 15 minutes to as much as three-quarters of an hour when take-off, landing and positioning are factored in. Indeed, more time was allocated to displays in the early 1950s than was during the tight scheduling of the sixties and seventies. The length of time for which the public are allowed access to the airfield has widened considerably also, which has been prompted no doubt by the greater level of attendance by visitors in their own cars. The need to open the gates earlier in order to avoid lengthy traffic queues has forced opening times from 12.00pm in some cases in the early years to 8.00am or even earlier in the 21st century.

Special bus routes, train services and the gates opening earlier each year has never made any significant change to the relentless problem of traffic, which may have reached saturation level at the annual Royal International Air Tattoo, where off-field parking has since been introduced. At this event public vehicles no longer park on the airfield itself, but in the surrounding fields.

Security reasons have also played a major part in the quite recent decision to park private vehicles off-field for reasons which are all too clear. However, this doesn’t seem to have concerned the RAF, which surely must face the same concerns.

For the time being, however, the remaining RAF-organised/sponsored displays have continued to allow for the more traditional on-field parking, thereby allowing the kind of scene reminiscent of the 1950s and 1960s of families picnicking around the family car, able to come and go. Recent prolonged spells of wet weather through the summer have prompted the organisers of the Royal International Air Tattoo to return to on-site parking, the logic of this being that the airfield at Fairford has a considerable expanse of concreted track and pan. This hardstanding is very much the answer to the previous years’ problems of waterlogged off-site fields which got so bad that unprecedented decisions were taken to cancel RIAT in 2008 and the second day of the RAF air show at Waddington the year before. Naturally other measures are in place to see this does not happen again but what is for sure in lean times is that it’s doubtful whether any event, no matter how big or small, can withstand the impact of more than one cancellation in a straight run. So with terrorists, weather, credit crunch and the occasional misplaced press report, here’s good luck to one and all for the future.