{131} Spirit-Path Stele for His Honor Yelü, Director of the Secretariat

By Song Zizhen of the Great Mongol Empire

This “Spirit-Path Stele” for Yelü Chucai is a classic example of the Chinese biographical genre. In Chinese practice, when a distinguished official passed away, the family would be expected to produce several different descriptions of his life. An “account of conduct” (xíngzhuàng) for the deceased would be submitted to the government; on it would be based any posthumous honors for the deceased, honors that could also substantially benefit his descendants. A “funerary epitaph” (mùzhì) would be carved on a stone block to be placed in the deceased’s tomb. A “spirit-path stele” (shéndào bēi) would be erected above ground near the approach to the tomb of the deceased. Finally, a “sacrificial address” (jìwén) would be recited to honor the deceased during the rituals of ancestor worship.

These genres have been called “social biographies,” because they were commissioned by the deceased’s family and were authored by persons in their private capacity as friends, family, or admirers of the deceased. Commissioning and writing such social biographies was a chance for prominent scholar-officials to express their friendship and admiration for deceased members of their ranks, but also to maintain connections with his family. Some highly regarded writers would even be paid to write such biographies. Texts in these genres were proudly included in the authors’ collected works, and the “accounts of conduct” were also preserved by the government. Thus preserved, these “social biographies” would become first drafts for later “historical biographies,” which would be commissioned for historical projects such as biographical collections, dynastic histories, and local gazetteers.1

Given the origin of these works in circles of mutual esteem, one might question how reliable they are as historical sources. Certainly, social biographies were written on the assumption that the object of the biography was an admirable man. Moreover, the dominant role of public service in validating social status meant that such admiration was directed above all toward the performance of particular roles in public service. The authors thus aimed more at providing a portrait of an ideal man of affairs, censor, financial specialist, military officer, or academician than at highlighting that man’s individual personality. Yet modern historians have noted countervailing forces that encouraged accuracy as well. The existence of government records against which the biographies could be checked, the embeddedness of these biographies in social networks, the concern of the authors for their own reputations as truthful writers, and the {132} general congruence between the authors’ categories of judgement and the subjects’ own ideals of conduct all worked to keep the biographies from departing too far from the consensus on a subject’s life. The problem was not so much that any one biography would be full of fictitious praise as it was that only certain categories of people, that is, those participating in the circles of social esteem created by a Confucian education, would likely receive biographies at all.2

Ila (Yelü) Chucai (1190–1244) was the kind of person whose virtues the “social biography” genre was ideally poised to capture. By origin, he was a scion of the former imperial Kitan lineage, but his family served the Jurchen Jin for three generations. After he entered Mongol service with the fall of the Jin’s Central Capital or Yanjing (present-day Beijing) in 1215, all the Song border officials noted his abilities; even the rather hostile Xu Ting admitted that he was tall, impressive, and a master of astronomy, poetry, the zither, and Buddhist meditation. But as the title of this stele inscription indicates, its focus is on his life and work as director of the Secretariat, that is, as the top civil official in North China under the Mongols. Portraying him as an impressive embodiment of the Chinese scholar-official ideal thus did not involve any great distortion of reality. One may notice, however, that this spirit-path stele completely ignores the likelihood, underlined by Xu Ting, that the Mongols themselves did not really pay much attention to his attempts to rebuild the government on Confucian lines.

The text for this spirit-path stele was written in 1268 by Song Zizhen (1188–1268), a scholar from Zhangzi County in southeastern Shanxi.3 His birthplace was part of Jin-ruled North China and, like many scholar-officials, he followed the Jin court south to Henan, but unusually, he soon returned to his war-torn homeland north of the Yellow River. He joined the pro-Song dynasty rebel Peng Yibin but then passed into the entourage of the pro-Mongol warlord Yan Shi when Peng Yibin was defeated and killed in 1225. Song Zizhen stayed in the service of Yan Shi and his sons until the enthronement of Qubilai Khan in 1260, when he was first appointed to office in the Mongol central government. Although he served briefly as Manager in the Secretariat before his retirement in 1265, his role was always more advisory than executive. As a local official, Song Zizhen had little contact with Ila Chucai during the heyday of his power in the 1230s, although Song did urge his warlord patron, Yan Shi, to cooperate with Chucai’s demilitarizing measures. After joining the central government, Song became a close associate of Chucai’s son, Yelü Zhu, however; they served together briefly in the local administration of Shandong in 1264.

Song Zizhen’s ties to Yelü Zhu were undoubtedly why he was chosen to write the spirit-path stele for Zhu’s father, Chucai. The latter had passed away in Qara-Qorum in Mongolia in 1244, and in 1261, after Qubilai moved the capital from Mongolia {133} to North China, he was interred according to his wishes in the Wengshan Hill cemetery north of Yanjing, on the outskirts of present-day Beijing. Probably in that year, Zhao Yan, a scholar in Zhu’s entourage, compiled an “Account of Conduct” for Chucai, while Li Wei compiled his funerary epitaph. Unfortunately, neither of these two works is preserved, but from surviving citations of them, it seems that Song Zizhen drew heavily on Li Wei’s previous social biography and likely on Zhao Yan’s as well.

Ila Chucai was of the former imperial Kitan lineage, which, as is explained in more detail in the Introduction, p. 44, had two alternative surnames, Ila (Ch. Yila) and Yêrud (Ch. Yelü). We know from his writings that Chucai used the form “Ila” throughout his life. However, after his death, his son Zhu preferred the form “Yelü” and had that used in all of his father’s social biographies.

Spirit-path steles were bound by many conventions, visible in this example. The title, carved in large graphs in the actual inscription, gave the subject’s surname, highest office, and honorific title, if any, but omitted his given name.4 The impersonal tone was preserved by referring to the subject throughout as gōng, which we translate as “His Honor.”5 The text begins with some general comments, then covers the subject’s ancestry, his birth and education, and then his official career chronologically, with most events dated to the year or to the year and moon. The biographical account finishes with his death (dated to the day) and a few anecdotes particularly illustrative of the subject’s personality. Then follows a description of the occasion for the spirit-path stele to be written, a prose summary of the person’s significance, and an ode extolling his character and public service.

The text of this spirit-path stele was printed in the Yuan wenlei, an anthology of the most distinguished writings of the Yuan dynasty, compiled by Su Tianjue in 1334 and blockprinted two years later. Since it was published during the Mongol Yuan dynasty, it observes the conventions protecting the sanctity of that dynasty. The personal names of the Yuan emperors are uniformly tabooed and replaced with the titles used in the ancestral temple, even though all the events took place long before any ancestral temples were created. References to emperors and to the dynasty itself are set off either by starting on a new line or by leaving a blank space above the name. Precisely because this is such a characteristic part of imperial rhetoric and of this genre, and because it is preserved only in this text among the five,6 we have tried in our translation to re-create it by placing such emphasized words in small capitals.

Song Zizhen’s text was intended to be an honest portrait of a widely admired man, who in his life had encountered much opposition. Yet it was also undoubtedly intended to speak to the time in which it was written. In 1268, the early hopes of Chinese {134} literati for Qubilai Khan were already withering, as the khan tired of their rigidity (as he saw it) and had begun to turn toward immigrant officials from the West. Chucai’s son, Yelü Zhu, had just been reinstated as “Grand Councilor”—by 1271 he would be dismissed again—and Song Zizhen himself was in the last year of his life. The spirit-path stele was thus both a public exposition of the Confucian program for the peaceful evolution of the Mongol dynasty and a warning against the malignant forces already at work to derail that evolution.

Spirit-Path Stele for His Honor Yelü, Director of the Secretariat

In the rise of our dynasty, its foundations were laid in the North. Because the Emperor Great Founder7 received the mandate with law-giving efficacy and reverently executed the heavenly chastisements, no kingdom could stand when his horse’s head turned against it. The Great Ancestor8 succeeded him and embraced all eight directions before stabilizing the Central Plains;9 on this side and beyond the Bars Lake,10 none did not yield humble vassalage. Thereupon he established the great government and ascended the imperial throne, building a new palace to call the regional lords11 to court. His intent was to plant a foundation that could not be uprooted and pass down a unity that could be continued.

And His Honor, a man of talents that commanded the age, met with the trend of the sovereign’s rise, serving as his mainstay among the ablest men of the court,12 and assisting him with his comprehensive learning. He assured the continuity of two reigns, aiding the establishment of two courts. He approved guidelines for the emerging age and unified institutions for the aftermath of pacification. He took {135} upon himself the weight of the civilized world (tiānxià), towering like a mountainous pillar in the midstream flow. For using all possible means to save living beings, he was inferior to no man in all past time.

His Honor’s personal name was Chucai, his courtesy name was Jinqing, and his surname was of the Yelü clan; he was an eighth-generation descendant of Tuyu, the Prince of Dongdan under the Liao dynasty.13 The prince begat Louguo, Viceroy and Director of Administration in Yanjing,14 the Viceroy begat the general Guin, the general begat Grand Preceptor Qalu, Qalu begat Grand Preceptor Qudugh, Qudugh begat Dingyuan General Nuilgha, and the Dingyuan General begat Deyuan, Grand Master for Glorious Happiness and the Military Commissioner for the Xingping Army; he was the first of his lineage to give his allegiance to the Jin dynasty.

Deyuan’s younger brother Yulu begat Lü, whom the commissioner for the Xingping Army took as a foster son and later treated as his own descendant.15 Emperor Shizong16 recognized Lü’s literary ability and righteous conduct, and he was thus appointed first as Academician Awaiting Instruction before being transferred to serve as Vice Director in the Board of Rites. When Emperor Zhangzong17 ascended the throne, Lü won merit for his strategies that stabilized the situation and was promoted to Vice Grand Councilor for the Board of Rites in the Department of State Affairs, passing away as Assistant Director of the Right in the Department of State Affairs, with the posthumous title “Duke of Civil Preferment.”18 He was His Honor’s father. His mother’s surname was Yang; she was posthumously enfeoffed as Lady of the Qishui Fief.19

His Honor was born on Mingchang 1, VI, 20 [July 24, 1190]. His father was a master of numerology and was especially advanced in the Supreme Mystery.20 {136} He privately told those who were intimate with him, “I am sixty years old, yet now I have begotten this boy, who is a fleet-footed foal of our family able to run a thousand lǐ.21 Someday he certainly will become a man of great ability; moreover, I predict he will serve a different dynasty.” Therefore, he chose the personal and courtesy names for this son based on a quotation from Master Zuo: “The talents are Chu’s but the use of them is Jìn’s.”22

Three years after His Honor was born, he was orphaned. His mother, the lady née Yang, was thorough in rearing and educating him, and by the time he was a little older, he knew to study diligently. At seventeen, there was no book he did not read, and in writing he already had an authorial style.

Under the Jin system, the grand councilors’ sons had the privilege of taking examinations for supplementary appointments as secretarial clerks.23 His Honor did not do this, so Emperor Zhangzong specially ordered him to sit without prior qualification for the regular exam, in which he received the highest ranking. Having passed a performance review,24 he was appointed as Vice-Prefect in Kaizhou Prefecture. In Zhenyou’s jiǎ/xū year [1214], Emperor Xuanzong25 left and crossed south over the Yellow River while the Grand Councilor, Wongian Chenghui,26 remained as viceroy in Yanjing. As the man handling the Department of State Affairs, he recommended His Honor to be Vice Director of that department’s Left and Right Offices. The next year the capital city fell, and so he became subject to Our Dynasty.

The Great Founder27 always had the ambition to swallow up the civilized world. At one point he sought out the surviving kinsmen of the Liao imperial family and summoned them to his traveling camp. At the audience, His Majesty said to His Honor, “The Liao and the Jin were rivals for generations. I have just taken vengeance on the Jin for you!” His Honor said, “Since the passing of my father {137} and grandfather, in all things your servant has borne allegiance to28 and served the Jin. As the son of a Jin vassal, how could I dare repay him by harboring divided loyalties and regard his ruler-father as my enemy?” His Majesty respected his words and kept him by his side, available for any consultation or inquiry.

Thus, in the summer, moon VI, of year jǐ/mǎo [1219], the imperial army launched an expedition to the west. On occasion of the sacrifices to the battle-standards, snow fell to a depth of three feet. His Majesty was worried by it, but His Honor said, “This is a sign that the enemy will be conquered.” And in the winter of gēng/chén [1220–1221] there was a great thunder. His Majesty asked His Honor about it, and he said, “It should mean that a soltan has died in the middle of a wilderness,” and indeed it turned out to be so. “Soltan” is a title of Turkestani kings.29

A man of the Xia, Chang Bajin, became well-known for his bow-making. So, surprised at His Honor’s non-martial role, he spoke to him, saying, “Our dynasty esteems the military, yet Your Honor, an enlightened man, wishes to advance with civil skills. Is not that the wrong way to go about it?” His Honor said, “Even assembling a bow properly requires a bowyer. How can one assemble the civilized world without a craftsman skilled in assembling the civilized world?”30 His Majesty, hearing this, was extremely pleased and from then on employed His Honor at increasingly confidential tasks.

At the beginning of the dynasty, there was no calendrical science. The Turkestanis memorialized31 that on the night of the fifteenth day of moon V there would be a lunar eclipse. His Honor said there would not be an eclipse, and indeed, at the time indicated there was no eclipse. The next year, His Honor memorialized that on the night of the fifteenth day of moon X there would be a lunar eclipse, {138} and the Turkestanis said there would not be. That night, the moon was eclipsed by 80 percent. His Majesty was greatly amazed by this and said, “There is nothing you do not understand about affairs in the heavens. How much more must you understand about affairs among men!”

In the summer of year rén/wǔ, moon V [June 1222], a comet was seen in the western quarter. His Majesty asked His Honor about this, and His Honor said, “It should mean that the Jurchen kingdom will change its ruler!” Over the course of the year, the Jin ruler died. From this point, whenever generals went out on campaign, His Honor was always ordered to divine omens of fortune and misfortune beforehand. His Majesty also burned sheep’s thigh bones32 to corroborate them.

Pitching camp at Iron Gate Pass in the country of East India,33 men in the imperial guard saw a beast with the form of a deer and the tail of a horse, green in color with a single horn. It could speak like a man, and said, “Your lord should return soon.” His Majesty thought this was uncanny and asked His Honor who said, “This beast is called jiǎoduān (“horn-end”). In one day it can travel 18,000 lǐ and can understand the languages of the barbarians in all four directions. This is a sign of the abhorrence of killing; Heaven must have sent it to warn Your Highness. Would that by taking up Heaven’s heart and sparing human lives in these several countries, Your Highness’s boundless blessings could be fulfilled!” That very day His Majesty issued an edict to withdraw the armies.

In the winter of year bǐng/xū, moon XI [November–December 1226], when Lingwu fell, the generals all vied with one another to capture lads, lasses, goods, and money.34 His Honor took only several volumes of books and two camel-loads of rhubarb, nothing more. Later, when the officers and soldiers fell victim to an epidemic, only those who obtained rhubarb recovered. Those whom he kept alive numbered several ten-thousand.

{139} After that, Yanjing had many bandits, who even drove carts to conduct their robberies; the local authorities could not stop them. The Perceptive Ancestor,35 who then was serving as Regent,36 ordered an imperial commissioner to accompany His Honor to go there posthaste particularly to settle the issue. After arriving, they made separate arrests and found that the robbers were all sons of influential families. Sundry family members came to give bribes and have them pardoned. The imperial commissioner was misled by them and wanted to memorialize against their punishment, but His Honor staunchly held that to do so would be unacceptable, saying, “Xin’an37 is not far away and still has not fallen. If we do not enforce discipline, I fear anarchy could result.” Sixteen men were then executed. The capital city became calm, and everyone could sleep securely.38

In the year of jǐ/chǒu [1229], the Great Ancestor39 ascended the throne, and His Honor planned the proceedings and set up rules of propriety. The order was for the imperial clansmen and honored commanders to all form into ranks and prostrate themselves. Indeed, the honored commanders’ practice of the ceremony of prostration began from this time. Most of those who came to the court from the tributary states ended up liable to death due to violating taboos, but His Honor said, “Your Highness has newly ascended the throne. May he not stain the white path.” His opinion was approved. Now, the reason for this expression is that the dynastic customs exalt white and treat white as auspicious.

At the time, the civilized world had just been settled and was still without regulations. The senior clerks40 in office all had the power to spare or kill entirely on their own authority. If anyone had defiant thoughts, then swords and rasps {140} followed, such that whole households were massacred without even babes in arms being spared. And in this prefecture or that district soldiers rose on the slightest pretext and attacked each other. His Honor was the first to raise this issue; all such actions were prohibited and eliminated.

From the Great Founder’s western campaign onward, the granaries and public storehouses had not a peck of grain or a roll of silk. Thus, the imperial commissioner Bekter41 and others all said, “Although we have conquered the Han men, they are really of no use. It would be better to get rid of them all and let the vegetation flourish to make pasture grounds.” His Honor promptly came forward and said, “So large is the civilized world, and so rich are the lands within the four seas, that there is nothing you might seek that you cannot obtain. But you simply do not seek it. On what grounds do you call them useless?” Thereupon, he memorialized about how the land tax, the commercial tax, and profits from monopolies on liquor, vinegar, salt, iron, and products of the mountains and swamps could raise 500,000 taels of silver,42 80,000 bolts of raw silk, and 400,000 piculs43 of grain annually. His Majesty said, “If it is truly as Our liege says, then this would be more than enough for the empire’s use. Our liege, try to make it happen.” Subsequently he memorialized to set up tax offices on ten routes, each with a commissioner and a vice-commissioner. He filled all the positions with Confucians,44 such as Chen Shike in Yanjing and Liu Zhong on the Xuandezhou Route, all of whom were the pick of the civilized world. Following on this, from time to time he would advance the teachings of the Zhou dynasty and of Confucius,45 stating, moreover, that “although the world may be won on horseback, it cannot be governed on horseback.”46 His Majesty concurred deeply. The dynasty’s use of civil ministers was thus due to His Honor’s initiative.

{141} Before this, the senior clerks on the routes concurrently held command over both the armies and the civilian land tax. They often relied on their wealth and power to arbitraily act lawlessly. His Honor memorialized that the senior clerks should exclusively administer civilian affairs, the myriarchs manage the armies, and the land taxes should be managed by the tax offices, with none of them exercising control over the other. This was then made the official system.47

Yet certain influential officials could not accept this. Šimei Hiêmdêibu48 stirred the Imperial Uncles49 into a rage, such that they sent a special messenger with a memorial claiming that His Honor “is entirely employing men formerly of the Southern dynasty;50 moreover, many of his kinsmen are among them, so we fear that he has subversive intent. He should not be employed in important positions.” Beyond that, they played on dynastic sensitivities to falsely accuse him in a hundred ways, determined to have him put to death. The issues came to implicate the executive administrators.

At the time, Chinqai and Niêmha Cungšai held the same rank as His Honor;51 put in a cold sweat by the accusations, they said, “Why was it necessary to change things so forcefully? We thought something like today’s controversy would happen!” His Honor said, “From the founding of the dynastic court until now, every {142} issue has been handled by me. What have you, sirs, had to do with it? If there are to be any criminal charges, I alone will bear them, and I certainly will not involve you.” His Majesty investigated the slanders and angrily drove away the messengers who had come to the court.

Within a few months, it happened that someone made an accusation against Hiêmdêibu. His Majesty, knowing that there was no collusion with His Honor, specially ordered him to handle the interrogation. His Honor memorialized, “This man [Hiêmdêibu] is haughty, without manners, and consorts with a petty-minded crowd; he easily invites defamation. But just now there is business with the South, so if this could be handled some other day, it would still not be too late.” His Majesty was a little unhappy but later said to his attendant officials, “This is a real gentleman; you all ought to imitate him.”

In the autumn of year xīn/mǎo, moon VIII [September 1231], His Majesty arrived in Yunzhong.52 The registers for the scheduled taxes in silver and cloth as well as grain stored in the granaries were all set out before him, and they completely matched the numbers His Honor had originally proposed. His Majesty laughed and said, “Our liege never left Our side, so how was he able he get money and grain to flow in like this? I wonder if the southern kingdom has a minister who can compare?” His Honor said, “Very many of my colleagues are more worthy. It is because your liege has no talent that he was left behind at Yanjing.”53 His Majesty personally poured him a great goblet of wine54 to honor him. That very day, he granted him the Secretariat seal and authorized him to administer its affairs. All, whether large or small, were entrusted to him alone.55

The senior official of Xuandezhou Route, Grand Mentor Tugha, let more than 10,000 piculs56 of official grain disappear. Relying on his past accomplishments, he secretly memorialized the throne seeking a pardon. His Majesty asked Tugha whether the Secretariat knew about this or not, and he replied, “They do not know.” His Majesty grabbed a whistling arrow and several times made as though to shoot Tugha before finally, after some time, yelling at him to get out. He ordered Tugha to report the matter to the Secretariat and make restitution. Further, he issued an imperial order that, from then on, all business be first reported to the Secretariat and only afterward memorialized for the attention of the throne.

{143} The eunuch Kümüs-Buqa57 memorialized to set aside a full 10,000 households for mining and smelting precious metals and growing grapes. His Honor said, “The Great Founder decreed that there would be no difference between the common folk behind the mountains and the people of our dynasty58 in that the soldiers and taxes they produce should be reserved for emergencies. It would be better to substitute for these tasks the remnant civilians of Henan,59 and not execute them. Moreover, the region beyond the mountains could be solidified.”60 His Majesty said, “What Our liege says is right.” He also memorialized that the civilian households in the routes had been depleted by a pestilence, so the Mongols, Turkestanis, and Hexi people dwelling locally should pay taxes and perform corvée the same as the other civilians living there.61 These proposals were all put into practice.

In the spring of year rén/chén [1232],62 the emperor proceeded to Henan. An imperial decree was issued to people in Shanzhou, Luoyang, Qinzhou, and Guozhou who had fled into hiding in the mountain forests and caverns, that if they welcomed the army and came to surrender, they would be spared from massacre. Some said that this sort only came to allegiance when compelled, that if pressure were lessened they would just go back to helping the enemy. His Honor memorialized that several hundred banners calling all refugees to return home should be deployed in the districts that had already surrendered. The number whose lives he saved was incalculable.

According to the institutions of the dynasty, enemies who resisted the command to surrender and cast so much as a single arrow or stone would then be killed without pardon. When Bianjing63 was about to surrender, the chief general {144} Subu’edei dispatched a man to come and report, adding that since this city’s defenders had resisted for many days and had killed or wounded many officers and soldiers, he intended to massacre them all. His Honor hastily forwarded a memorial saying, “The generals and soldiers, in exposing themselves to hardship for these many decades, have been fighting simply for land and people. If they get land without people, then what use will it be?” His Majesty was in doubt and made no decision, so His Honor again memorialized, saying, “All the craftsmen of bows, arrows, armor, weapons, gold, jade, and the rest, along with the wealthy families, both officials and commoners, have crowded into that city. If you kill them, then you get nothing from them, and your effort will be all in vain.” His Majesty then began to agree. He issued an edict that, apart from the whole Wongian clan,64 all the rest should be spared. At the time, those in Bianjing who had fled there from the warfare numbered 1,470,000 households. His Honor further memorialized that those in the classes of artisans, craftsmen, Confucian scholars, Buddhist monks, Daoist priests, physicians, and diviners should be resettled throughout Hebei with assistance from official funds. Thereafter, when the cities along the Huaihe and Hanjiang rivers were seized, this procedure was followed as an established precedent.

Previously, when Bianjing had not yet fallen, His Honor memorialized to dispatch a messenger into the city to search for and find the fifty-first generation descendant of Confucius, Kong Yuancuo, and reaffirm his enfeoffment as Duke Who Propagates the Sage.65 He ordered ritualists and musicians who were scattered as refugees to be gathered together and many famous Confucian scholars such as Liang Zhi to be taken into protective custody. In Yanjing he set up an editorial office and in Pingyangfu66 a canonical texts office in order to initiate civil administration.67

When Henan had first been conquered, the number of those taken prisoner was incalculable, but then when they heard that the great army was returning north, 80 to 90 percent of them fled away. An imperial edict was issued that anyone who took in or helped fugitive civilians by giving them food or drink would be killed. Whether in a walled city or a rural village, if one family violated this order, then the others, too, would all be implicated in the guilt. As a result, the common folk were dreadfully afraid, and even fathers and sons or elder and younger brothers, once any had become prisoners, did not dare to look each other in the {145} eye. The fugitives had no way to get food and collapsed and died on the roads, one upon another. His Honor calmly entered the audience hall and, explaining the situation, said, “The reason why we have spared and succored the common people for over a decade is so they can be useful to us. When victory and defeat are undecided, one must consider that people may ally with the enemy. But now the rival empire has been destroyed. If its people run away, where can they go? How can several hundred people be faulted on account of a single escaped prisoner?” His Majesty realized the wisdom of this and suspended the order.

Though the Jin dynasty had fallen, a mere twenty or so prefectures in the Qinzhou-Gongzhou region still had not submitted for several years. His Honor memorialized, “Our people who fell afoul of the law and fled to the Jin kingdom have all congregated there. They fight so hard simply because they fear death. If you grant that they not be killed, then they will surrender on their own without any attack.” The edict was issued, and all opened their city gates and surrendered. Within a month, everywhere west of the mountains68 was pacified.

In the year jiǎ/wǔ [1234], by imperial edict, there was a census of households and the powerful vassal Qutughu was put in charge of it. At the beginning of the dynasty, the focus was on capturing territory, so any place that surrendered was simply left to those who surrendered. Each single hamlet and person had its own ruler with no general administration over them. It was only from this period that they came under the jurisdictions of prefectures and counties.

The court ministers as a body wanted to count every adult male as head of a separate household. His Honor alone thought this was unacceptable. Everyone said, “Whether it be our dynasty or the kingdoms in the West,69 there is none that does not take each adult male as head of a separate household. How can you reject the great dynasty’s laws and instead follow the policies of the fallen dynasty?” His Honor said, “Since ancient times, those in possession of the Central Plains have never once taken each adult male as head of a separate household. If you actually do that, then you could collect a single year of taxes, but afterward people will scatter in flight!” In the end, His Honor’s opinion was adopted.

At that time, the slaves that the great princes and vassals, as well as the generals and officers, had taken as prisoners were usually lodged in the various districts, making up almost half of the whole population (tiānxià). His Honor therefore memorialized that in conducting the census of households they all be classified as registered civilians.70

{146} In the year yǐ/wèi [1235], the court proposed that Turkestanis go on campaign against the South while Han men campaign in the West. This was thought to be a winning strategy.71 His Honor absolutely opposed it, saying “The Han lands and the Western regions are several thousand lǐ distant from each other. By the time the units would get to the land of the enemy, the transferred horses and men would be exhausted and unfit for service. Moreover, the living environment is different from what they are adapted to and would certainly breed epidemic diseases. It would be better for each to be sent on campaign in their own lands, which would seem to have double benefits.” The debate lasted more than ten days before the original proposal finally was put to rest.

In year bǐng/shēn [1236], His Majesty assembled the princes and honored vassals and, personally offering a goblet of wine, toasted His Honor, “The reason why We have so sincerely trusted Our liege is that the Late Emperor commanded it. Without Our liege, then the civilized world would not have seen this day. We rest high and peaceful on Our pillow due to the efforts of Our liege.” It is the case that in the Great Founder’s last years he several times instructed72 His Majesty, saying, “This man is Heaven’s gift to our family; some day, you should entrust all the affairs of the empire to him.”73

That autumn, in moon VII, Qutughu came to present the census results to the throne. He proposed that the prefectures be divided up and bestowed on the princes and aristocratic families as appanages for their household expenses.74 His Honor said, “Big tails can’t be wagged; this could easily produce conflict. It would be better to give them additional gold and silk, enough to show your benevolence.” His Majesty said, “Patrimonies have already been conferred on them.” His Honor went on, “If civil officials are set up and always follow orders from the court, and if they are not allowed to arbitrarily levy taxes apart from the regular quotas, the difference [for the court’s interests] would be sustainable in the long term.” This was approved. That year, the civilized world’s taxes were fixed for the first time. Every two households would pay one catty of silk to supply official needs, while every five households would pay one catty of silk for the family to whom they had been granted. For each mǔ,75 high-grade fields would pay a grain {147} tax of three and one-half dǒu,76 middle-grade fields would pay three dǒu, low-grade fields two and one-half dǒu, and irrigated fields five dǒu.77 Commercial taxes were set at one part per thirty, and salt was set at forty catties per tael of silver. All the above were made perpetual rates. The dynasty’s ministers all said the taxes were too light, but His Honor said, “In the future, interest certainly will be collected [on tax arrears],78 and then the exactions already will be heavy.”

At the beginning of the dynasty, robbers and bandits were so rife that merchants and traders could not travel. Thus, an order was issued that wherever there were losses due to robbers who escaped, if the main culprits were not apprehended within a full year, then the civilians of that route would have to pay compensation for the stolen goods. Over time, the accumulated fines reached a vast number. As for the local civil officials, they would have to borrow silver from Turkestanis, and the amount owed each year would double.79 The next year, with the interest added, it would double again. This was called the “lamb profit.” Such debts accumulated without end, often destroying families and scattering clans, to the point where wives and children had to be pawned; yet in the end they could not be paid off. His Honor made a request of His Majesty, and all the debts were repaid in silver with official funds, totaling 76,000 dìng. He memorialized as well that, from then on, no matter how many months or years have passed, when the interest on a loan has come to equal the principal, then the loan will no longer bear interest. This then became a set rule.80

The aide Toghan memorialized about the selection of virgins,81 and by imperial order the Secretariat was to promulgate an edict for circulation. His Honor {148} received the order but did not send it on downward. His Majesty was angry and summoned him to explain. His Honor said, “There are still twenty-eight virgins in Yanjing from the previous round of elimination, more than enough to meet orders from the northern palace. Yet Toghan has transmitted a decree wishing to implement yet another general selection. Your liege fears that this will be a severe disturbance for the common folk and was just about to memorialize advocating reversal.” His Majesty thought about this for a long while and said, “All right.” The decree was then canceled.

[Toghan] also wanted to requisition selected mares from the Han lands. His Honor said, “What the Han lands have is only silkworm threads and the five grains; it is not a place that produces horses. If this is carried out today, then later it certainly will become a precedent. This would be to burden the civilized world for no good reason.” So his request to stop the requisition was followed.

In the year of dīng/yǒu [1237], there was a vetting of specialists in the Three Teachings. Buddhist monks and Daoist priests were examined in the scriptures. Those who were proficient were given certificates of ordination and permission to dwell in monasteries or temples. The selected Confucian scholars were returned to their homes.82 Previously His Honor had said, “Among Buddhist monks and Daoist priests many are just evading corvée; a qualifying examination should be held.” At this point it was first implemented.

At the time,83 the princes and aristocratic in-laws could use the post-road horses as they pleased, and the envoys were awfully numerous. Horses everywhere were in short supply, so civilians’ horses would be seized high-handedly as mounts, raising commotions on the the roads between cities. When such travelers reached the next station, they would demand a hundred things, and if the food service were a little slow, then the staff would be horsewhipped; the people working in the hostels could not stand it.84 His Honor memorialized that paizas and authorization {149} letters85 should be given together with regulations on rations of food and drink to be established, so that the evils of the system were first reformed.

He followed up by setting forth ten proposals for tasks of the time,86 to wit: 1) making rewards and punishments reliable; 2) correcting divisions of status; 3) issuing official salaries; 4) enfeoffing meritorious vassals;87 5) judging censures and commendations; 6) determining material resources;88 7) testing craftsmen; 8) promoting agriculture and sericulture; 9) fixing local tribute gifts; and 10) setting up water transport. Although His Majesty could not implement them all, still he made use of them at times.

A Turkestani man, Asan-Amish,89 charged His Honor with using 1,000 dìng90 of official silver for private purposes. His Majesty summoned His Honor and asked him about this. His Honor said, “Your Highness, try to think carefully about this. Has there been an edict to pay out some silver?” His Majesty answered, “We too recall that there was an order for repairs to this palace that used 1,000 dìng of silver.” His Honor said, “That was it.” Several days later, His Majesty held an audience at Wan’an Hall91 and summoned Asan-Amish for questioning. He admitted making a false accusation.

An indictment of the tax clerks of Taiyuanfu Route for embezzlement was reported to the throne, and His Majesty chided His Honor: “Our liege says that the teachings of Confucius can be put into practice and that Confucian scholars are all good men, so how do we have this sort?” His Honor replied, “This vassal-son hardly would wish to defame as unrighteous the teaching of [subjects’ honor to] the ruler-father. Yet sometimes there are unrighteous people. Wherever there is a kingdom or a family, all have followed the teaching of the Three Fundamental Bonds and Five Constant Virtues without exception, 92 just as Heaven has the sun, moon, and stars. How could the Way that has been continuously practiced in all {150} ages be abandoned by our dynasty alone simply on account of one man’s fault?” His Majesty’s misgivings were thus allayed.

In the year of wù/xū [1238] there were severe drought and locust losses in the civilized world. His Majesty asked His Honor about methods to protect against these. His Honor said, “Your liege begs that this year’s tax collections be temporarily stopped.” His Majesty said, “We fear that there will not be enough for the needs of the state.” His Honor said, “At present the granaries have enough to sustain us for ten years.” It was permitted.

At the start, registration of the households in the civilized world yielded 1,040,000, but by this time, 40 to 50 percent had absconded. Still, taxes were levied by the old quotas, and the whole society was plagued by this. His Honor memorialized to remove 350,000 fugitive households from the rolls. The people depended on this for their peace.

Yanjing’s Liu Quduma93 secretly linked up with powerful personages and bought the commission on the civilized world’s household requisitions94 with a bid of 500,000 taels. Sheref ad-Din bought the commission on [collecting of rents from] the civilized world’s government-owned corridor housing,95 land foundations, irrigation systems, and pigs and chickens with a bid of 250,000 taels. Liu Tingyu bought the commission to manage the liquor monopoly in Yanjing with a bid of 50,000 taels. There was also a Turkestani who bought the commission to manage the civilized world’s salt monopoly with a bid of 1,000,000 taels. It got to the point where even the civilized world’s river moorages, bridges, and fords were all sold on commission. His Honor said, “These men are all crooks, swindling those below them and deceiving those above them. The damage they are doing is very great.” He memorialized to get rid of all of them.96 He once said, “Initiating one advantage is not as good as eliminating one harm; generating some measure is not {151} as good as eliminating some measure. Men today all think Ban Chao’s words are just clichés, but since earliest antiquity this has been the final word.”97

His Majesty was always fond of liquor, and in his later years this was especially the case, as he spent his days drinking his fill with the great vassals. His Honor repeatedly remonstrated with him but was not heeded. So, he held the metal mouth of the liquor spout and said, “This iron has been corroded by the liquor. If that is the effect even on this, how indeed could a man’s internal organs not be damaged?” His Majesty was pleased and bestowed on him gold and silks, while also ordering that his attendants send in no more than three zhōng a day.98 At this time, there were no worries in any direction, and His Majesty became rather negligent in attending to government affairs. Corrupt and twisted men took advantage of this interval to gain entry.

From the year gēng/yín [1230], His Honor had fixed the tax quota at 10,000 dìng; once Henan had fallen and the number of households had multiplied, then it was increased to 22,000 dìng. But the Turkestani translator An Tianhe arrived from Bianliang99 and spared no effort to serve His Honor, hoping to be recommended employment. Although His Honor praised and encouraged him, in the end his ambitions were not satisfied. So he ran to visit Chinqai and used a hundred strategems to play one man against the other.

The first thing he did was to induce the Turkestani Abduraqman100 to bid for the commission on scheduled taxes to be increased to 44,000 dìng. His Honor {152} said, “Even though 440,000 could actually be raised, it would only be by applying strict laws and restrictions and would just be a covert seizure of the people’s gain. Desperate people becoming robbers would not be good fortune for the state.” Yet the intimate attendants and aides were enticed. His Majesty, too, was rather beguiled by the group opinion and wanted to order that the increase be implemented on a trial basis. His Honor contested it, arguing this way and that, his voice and expression both growing stern. His Majesty said, “Do you really want a fistfight over this?” His Honor’s efforts could not carry the day, and with a great sigh he said, “Since the auctioning of tax profits has become ascendant, there certainly will be people who follow in these men’s footsteps and arrogate their powers. Poverty and misery for the people will originate in this, and government authority will become diffused among many parties.”101

His Honor stood firm at court with a serious countenance and was unbending in any way, as he desired to sacrifice his own body for the civilized world. Whenever he expounded on what brought advantage or disadvantage to the dynasty or joy or sorrow to the people, his manner of expression was sincere and his diligence ceaseless. His Majesty would say, “Are you going to start crying for the common folk again?” Nonetheless, he treated His Honor with ever greater respect. His Honor managed the state for a long time, and whatever salary or bonus he received, he distributed among his clansmen, never using his office or title for private advantage.

Someone urged him to take present opportunities to “widely spread the family tree”102 as a method to secure his own base.103 His Honor said, “Giving them money is enough to make their lives happy. Supposing I put them in government posts, then if there were unworthy ones who violated the regular statutes, I could not abandon the public laws and succumb to private feeling for them. ‘A crafty rabbit has three burrows’—that is not a motto I live by.”

In the spring of year xīn/chǒu, moon II [March/April 1241], His Majesty became seriously ill, such that his pulse stopped. Medicines were not able to cure him.104 The Empress did not know the reason and summoned His Honor and asked him about it. At the time, the corrupt ministers had usurped the government, peddling justice and selling office. They had ordered that all the kingdoms {153} be put under the control of Turkestanis.105 So His Honor replied to the Empress, “The imperial court now employs the wrong men, and the civilized world’s prisoners certainly include many who have been falsely charged. Therefore disturbances in the heavens frequently occur. An amnesty should be proclaimed throughout the civilized world.” When he drew for proof on how Duke Jǐng of the ancient Song state had gotten the planet Mars to leave his state’s constellation,106 the Empress became anxious to implement the measure. His Honor said, “Without the lord’s command it cannot be done.” Shortly afterwards, His Majesty revived a bit and the Empress memorialized about it. Unable to speak, His Majesty simply nodded his approval. When the amnesty was issued, his pulse again became active.

By moon XI (December 1241), His Majesty had long stopped taking medicine. His Honor several times divined by the Great Monad107 that he should not hunt game, memorializing about it several times. His attendants all said, “If he does not ride and shoot, how will he enjoy himself?” His Majesty went hunting for five days and passed away.108

{154} In the year gǔi/mǎo [1243], the Empress asked His Honor about an heir and the succession. His Honor said, “This is not something which a minister of a different lineage should discuss. Of course, there is the testamentary edict of the Late Emperor. Following it would be a great blessing to the altars of state.”109

As Abduraqman had just seized power at court through bribery, everyone else with power toadied to him. He feared only that His Honor would block his doings. So he tried to bribe His Honor with 50,000 taels of silver. But His Honor would not accept it, and whenever Abduraqman’s policies were harmful to the people, he immediately put a stop to them.

At the time, the Empress had already assumed the regency and she delivered to Abduraqman blank sheets with the imperial seal affixed, with the order to have them filled in with writing, as he liked. His Honor memorialized, saying, “The civilized world is the Late Emperor’s world.110 Laws and institutions, rules and regulations: all issued from the Late Emperor. One must hope that it will continue to be thus, so your liege dares not receive this directive.” Soon after there was another edict ordering that, since Abduraqman’s memorials accord with reason, any scribe who would not write in his views on those sheets would have a hand cut off. His Honor said, “The Late Emperor entrusted all affairs of army and state to this old vassal. What is the point of giving orders to scribes? If the policies are reasonable, then naturally I will honor them, but if they are unreasonable, then I will not hide even from death in my resistance. How could I care about a severed hand?” He thereupon said in a severe tone, “This old vassal served the Great Founder and the Great Ancestor for more than thirty years and has certainly never turned his back on this dynasty. Even an Empress Dowager cannot kill a minister who has been without fault.” Although the Empress resented his defiance of her, because he was a senior meritorious minister from the previous reigns, she bent to him out of respect and awe.

{155} In that year, His Honor grew sick and passed away in office on V, 14 [June 20, 1244], after enjoying fifty-five years of life.111 All Mongols cried for him as if they were mourning a relative, the Qorum markets closed in respect for him, and music and entertainment ceased for several days. Among the scholar-officials of the civilized world, there were none who did not weep sorely and mutually mourn him. On Zhongtong 2, X, 20 [November 14, 1261], he was interred on the sunlit side of Wengshan Hill, east of Yuquan,112 in accord with his last testament.

He was buried with his deceased wife, the lady née Su, of the Qishui Fief.113 He had previously married a lady of the Liang family, from whom he was separated by the chaos of war, and who died in Fangcheng, Henan.114 She had given birth to a son, Xuan, who was supervisor of the granaries in Kaipingfu before he passed away.115 The lady née Su was the daughter of Su Gongbi, the prefect of Wēizhou and a fourth-generation descendant of Master Su Dongpo.116 Her son was Zhu, who is now serving as the Grand Councilor on the Left of the Central Secretariat. There are eleven grandsons, named Xizhi, Xibo, Xiliang, Xikuan, Xisu, Xizhou, {156} Xiguang, Xiyi, and so on.117 There are five granddaughters, who have been married into noble families.

His Honor’s natural endowment was exceedingly gallant, in every way going beyond the ordinary human measure. Though official correspondence filled his desk, he would grant this and reply to that on left and right, in everything fitting the case at hand. Also he was able to discipline himself with loyal dedication, once calculating the civilized world’s nine-year tax revenue without a hair’s breadth of discrepancy by staying up all night working on it sleeplessly.

Ordinarily he would not laugh or talk nonsense, and one might suspect he was cool and aloof, yet once he engaged with someone, his warm cordiality was unforgettable. He was not a regular drinker, and while only occasionally gathering for entertainment with friends and guests, he went from morning to evening sitting upright.118 Throughout his life he paid no attention to making a living119 and never once asked about the income and expenditures of his family finances. When he died, someone slandered him, saying “His Honor served as Grand Councilor for twenty years, during which the tribute and presents of the civilized world flowed into his private coffers.” The Empress dispatched a man of the imperial bodyguard120 to inspect his place. Only a few fine zithers121 and a few hundred rubbings of old inscriptions were found.122

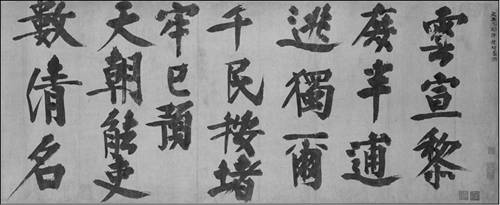

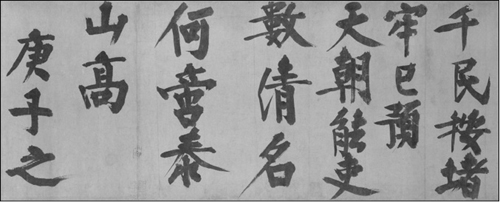

{157} Poem by Ila Chucai in his own calligraphy, addressed to the local official Liu Man upon the official’s departure from office.

He was zealous in his love of study, which he did not dispense with morning or night. He once admonished his children, saying, “No matter how numerous your official duties, the days may belong to the office, but the nights belong to yourselves and you can always study then.” In his learning, he aimed for comprehensiveness. Astronomy and calendrics, medicine and divination, mathematics and mental computation,123 musical pitch, Confucianism and Buddhism, and the scripts of various countries—there was none he did not grasp thoroughly. Once he said that the understanding of the five planets is more precise in the Western calendar than in the Chinese one,124 and so he made the Martabah Calendar, which should be the Turkestani name for calendar.125 Moreover, when he found that their {158} measurements of solar eclipse progression differed from the Chinese because of accumulated discrepancies in the Daming Calendar,126 he set the “Duke of Civil Preferment’s Yǐ/wèi [1235] Almanac”127 and promulgated it throughout the world.

His Honor having been interred for seven years,128 the Grand Councilor129 brought to me the “Account of Conduct” composed by the Presented Scholar Zhao Yan130 and entrusted me with writing a stele inscription and ode based on it. The dynasty inherited a state of great chaos, in which Heaven’s bonds were ruptured, Earth’s axis was broken, and human principles were eclipsed. What is called re-creating the bonds of husband and wife and reestablishing the relation of father and son—truly there was such a need!131 In addition, the regimes of the North and South132 in all things were recalcitrant toward each other. Those who came and went making use of the situation were all from different countries, with mutually unintelligible languages and incongruent aims. Yet just at that time, His {159} Honor, as a single student standing alone at the head of the court, still desired to practice what he had learned—how impossibly difficult it was! Fortunately, relying on an enlightened Son of Heaven ascending the throne, his admonitions were heeded and his words were heard. He shook out his sleeves and strode straight ahead, vigorously pressing on with no regrets. Even though not more than two or three out of ten of his policies saw implementation, nonetheless the men of the civilized world have all shared equally in the blessings they conferred. If, at a time like this, His Honor had not existed, then no one knows indeed what would have become of the human race.

The ode reads:133

The rise of noble kings

Depends on worthy men.

But who will take that role

Cannot be known ahead.

Aheng came back to Shang,134

Shangfu returned to Zhou:135

They rose like clouds in just a day,

And hist’ry made for endless years.

The scarlet mists announced his rise;

A dragon flew in wint’ry steppes.

Commanders marshaled righteous troops

To pacify the civ’lized world.

Confucians came in their due time

And stitched again opposing sides.

In earnest effort he excelled—

Just him, Director in the Court.

And what would be His Honor’s way?

To harmonize his ruler’s realm.

The foal of royal tutor’s line,

{160} The duke who honored culture’s son.

The flawless jade was grand, how grand,

A splendor that secured the state!

The monarch said, “Behold the man

Bestowed by Heav’n upon our clan!”

A double fire cohering flashed:136

The Mandate now has been transferred.137

The Heavens spin and Earth will turn138

As though to start all things anew.

In court and country all affairs

Entrusted were to his wise care

Our state, our people all as one.

“You effect and you shall act!”139

His Honor knelt and bowed his head,

“How dare I not to try?” he said.

Beginning with the thearchs’ texts,

He raised up humane principles.140

The mighty men across the realm,

Took killing as their wanton sport.

Covertly they robbed the folk,

And played with soldiers all around.141

{161} But once his noble cry went out,

It traveled faster than a gale.

He took command of summoned braves

To pen and cage the bloody beasts.

The wise and good had hidden well,

Behind stout passes, holding out.142

In deep disguise went noble men

To seek to live amongst the weeds.

Yet choosing each to fit the task

He richly built the house of state.

He cast his net in every clime

To snare the rarest treasured game.143

To fill the stores with good supply

And issue wide the silk and grain,

His Honor was for just this time

Like Xiao He in the keep of Han.144

To form anew the halls of power145

And burnish bright the legal norms,

His Honor was for just this time

Like Xuanling of the halcyon Tang.146

{162} With captives chained in endless lines,

The lands were strewn with corpses stiff.147

We had been warm but now were cold;

We had been full but now were starved.

In cities tense with dreadful siege

Each breath was breathed on borrowed time.

The captives’ bonds we then untied,

And brought the dying back to life.

The living multiplied and thrived,

Instructed well on nurturance.

And to today, each family

Receives the blessings of his care.

While Heaven high above us lies

What happens here is clearly known.

So bless’d is now the primal heir148

To grasp again the hinge of state.

His Honor’s merit’s well archived;

His name lights up dynastic tales.

The mighty, rich, and full of years

Will mourn and celebrate him here.

How lush, how lush this new grave-path

With surge, with surge will flow the spring.149

Immortal is his noble name,

For myriad years his verdant fame.

1. The distinction of “social” and “historical” biographies was first drawn in a seminal article by Peter Olbricht (1957).

2. In addition to Olbricht above, see Schneewind (2009) and Twitchett (1992, 62–83; and 1962) on the strengths and weaknesses of Chinese social biographies and the historical biographies based on them.

3. Details of his life, as summarized in his own social biographies, are given in Su Tianjue (1996, 10.199–203), and YS 159.3735–37. The date of his death is often given as Zhiyuan 3 (1266) because that is the last year mentioned in his Yuanshi biography. Su Tianjue’s biography, however, explicitly states that he died in Zhiyuan 5 (1268), the only death-date that is compatible with his known authorship of the Chucai memorial inscription in 1268.

4. Since Mongols and Uyghurs did not use their family or clan names in the Chinese fashion, their surnames were simply omitted and only their title given.

5. For those of princely rank, the title wáng, “prince,” would be substituted.

6. Since Zhao Gong’s “Memorandum” and Peng and Xu’s “Sketch” were entirely about foreign, non-Song rulers, there would, of course, be no occasion for them to show such respect. Li Xinchuan’s history and Zhang Dehui’s “Notes” in their original form presumably followed such conventions for their own Song and Mongol rulers, respectively. However, the oldest surviving texts of both of them postdate their original dynasty and, as commonly occurred when such works were reprinted in later dynasties, eliminated all such honorific features.

7. Ch. Tàizǔ, the posthumous temple name of Chinggis Khan (r. 1206–1227).

8. Ch. Tàizōng, the posthumous temple name of Chinggis Khan’s second son, Öködei or Ögedei Khan (r. 1229–1241).

9. Ch. Zhōngyuán; these are the plains along both sides of the Yellow River in the Henan area and by extension the entire heartland of North China.

10. Ch. Púlèi. This is the modern Barsköl or “Leopard Lake” in the Barköl Kazakh Autonomous County in Xinjiang. The Chinese name used here dates from the Han dynasty’s campaigns in the region over a millennium before the Mongol era.

11. The “new palace to call the regional lords to court” evidently refers to Öködei building Qara-Qorum. “Regional lords” translates Ch. zhūhóu 諸侯, lit., “the many lords.” Often translated as “feudal lords,” this phrase stems from China’s classical age, the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BC), when the Zhou king ruled their newly conquered dominions through a system of autonomous, hereditary lordships; Li 2003; Pines 2020. As it broke down into “Warring States” in fifth to third centuries BC, this decentralized but peaceful early Zhou system was viewed nostalgically as a time of perfect sage rule. Even after China transitioned into an enduring system of bureaucratic rule through appointed functionaries, the idea of the emperor ruling through zhūhóu or hereditary regional lords continued from time to time to be part of both the idealized image and the reality of rulership. Here it has been repurposed to give an air of classical antiquity to the Mongol system of princely appanages.

12. Ch. kuòmiào 廓廟, understood here as a synonym of, or perhaps an error for, lángmiào 廊廟.

13. On Tuyu (Ch. Bei; 900–937), see his biography in LS 72.1209–11.

14. On Louguo (d. 952), see the brief biographical notice in LS 102.1501.

15. On Ila Lü (1131–1191), see his biography in JS 95.2099–101.

16. The Jin emperor Yong (Jurchen name Uru); his posthumous temple title Shizong means “Renovating Ancestor” (r. 1161–1189). Note that by using these temple names, Song Zizhen was implicitly agreeing with Ila Chucai’s own sentiment that the Jin dynasty had been the legitimate dynasty in its own time, until it was superseded by the Mongol Empire.

17. The Jin emperor Jǐng (Jurchen name Madaka); his posthumous temple title Zhangzong means “Model Ancestor” (r. 1189–1208).

18. “Civil Preferment” is Chinese wénxiàn 文獻. This title was later used by Chucai himself. On the bureaucratic and hereditary titles mentioned here, see the Introduction, pp. 32–33, 34.

19. Qishui is a river in present-day Shaanxi province, west of Xi’an. However, such titles were purely honorary and did not necessarily have anything to do with the place. Indeed, the title Prince of Qishui was quite common in the Liao dynasty, which never ruled that area at all.

20. Ch. Tàixuán 太玄, referring both to the book, Taixuan jing (“Canon of the Supreme Mystery”), by the Han-period Confucian Yang Xiong (53 BC–AD 18), and to the method of divination expounded in that work. This divination was modeled on the more ancient divination text, the Yijing (or I Ching), the “Classic of Changes.” It organized the possible outcomes of divination according to stacks of four lines, each either unbroken, broken once, or broken twice. See the translation and study of the work in Nylan 1993.

21. A lǐ is a little over half a kilometer or a third of a mile.

22. From the “Zuo Commentary” or Zuozhuan, Xianggong chapter, year 26; cf. Legge [1872] 1991, 521 (text), 526 (translation). Yelü Chucai’s name, Chǔcái, means “talent (or material) of Chu,” and his courtesy name, Jìnqīng, means “liege of Jìn.” Chu (modern Hunan and Hubei along the Middle Yangtze) and Jìn (modern Shanxi) were two rival states in the Springs and Autumns period (722–484 BC); the Zuozhuan is the main source for the history of that period.

23. Such examinations were not as competitive as the regular exams and thus provided an easy way to get a first step into the official ranks.

24. Regular performance reviews were conducted for those holding office every three years. This implies that Ila Chucai held some minor post, in which he did well, before being appointed as vice-prefect.

25. The Jin emperor Xun (Jurchen name, Udubu); his posthumous temple title Xuanzong means “Comprehensive Ancestor” (r. 1213–1224).

26. Chenghui’s Jurchen name was Fuking; he appears in Li Xinchuan’s history exclusively as Wongian Fuking. Yelü Chucai’s biography in the Yuanshi adds that the one handling the Department of State Affairs was Wongian Chenghui/Fuking; see YS 146.3455.

27. That is, Chinggis Khan.

28. Lit., “faced north.” Rulers in China always held court facing south; to face north was thus to show submission and allegiance.

29. Based on differing Arabic or Persian dialectal forms, Chinese sources transcribe this title sometimes as sultan and sometimes as soltan. “Turkestani” here is Ch. Húihú. Originally meaning the Uyghur Empire in Mongolia, it later evolved into Húihúi, meaning “Muslim.” Here we translate it as “Turkestani”; see the Introduction, p. 27.

30. The Chinese here uses the same verb (zhì 治) for assembling or “governing” a bow, as a bowyer or bow-maker would do, and “assembling” or governing the civilized world. Our English translation follows the need to find a single verb that would make the analogy plain. Analogies of Confucian governance with craftsmanship or medical practice were common in the Mongol Empire; see “Notes,” p. 172; Shinno 2016, 30. These analogies were particularly apt because in the Mongol administrative system artisans and physicians had high-level tax exemptions that exemplified the Mongol rulers’ appreciation of their skills. On this system of tax exemptions and Confucians’ role within it, see Shinno 2016, 40–41; Atwood 2016, 279; Atwood 2004, 249–50, 281–82; Endicott-West 1999; Allsen 1987, 120, 159, 210–16; Dardess 1983, 14–19.

31. In the Chinese bureaucratic system, all policy initiatives were supposed to be first submitted in writing by high officials to the emperor, who would then accept, modify, or reject them, again in writing. Such “formal policy statements submitted to the ruler” (Kroll 2015, s.v. zòu, 632b) and the process of submitting them were both designated in Chinese as zòu 奏, conventionally translated as “memorial” or “to memorialize.” This term is thus used for all of Chucai’s communications with the Mongol emperors.

32. As was described by Peng Daya and Xu Ting (“Sketch,” p. 108), Mongolian diviners usually used shoulder blades of sheep and not thighbones. It is unclear if this is just Song Zizhen’s mistake or if other bones were also sometimes used.

33. The background and subsequent history of this famous incident in later Chinese and Mongolian histories is explored in de Rachewiltz 2018 and Ho 2010. One should note, however, that its geography was confused by a misunderstanding of the originally Mongolian indications of direction. In Mongolian, the most common directional system is based on facing south, so that “left” also means “east.” However, there is another directional system attested in the Mongol Empire based on facing east. In this system, “left” means “north.” Based on the historical context, Chinggis Khan must have been attempting to return home via the mountain route along the Indus River up to Khotan in the Tarim Basin, and thence back to Mongolia. Thus, he camped in the “left” or “northern” part of India, not the eastern part. It is also worth noting that there are many passes called “Iron Gates” in Chinese and Mongolian sources; this must be one in what is now northern Pakistan, where rhinoceroses were found until the Mughal era.

34. This was the final campaign against the Tangut kingdom, the Western Xia. Chinggis Khan died in 1227 during this campaign.

35. Ch. Ruizong, the posthumous temple title of Chinggis Khan’s youngest son, Tolui.

36. “Regent” translates the Chinese title jiānguó 監國. It is unclear, however, what Tolui’s actual title, if any, was at the time. After Tolui’s sons, first Möngke and then Qubilai, seized power from Öködei’s family and ascended the throne, Tolui’s role in the period between Chinggis Khan’s death and Öködei’s enthronement was exaggerated as a way of supplying a precedent for their own seizure of power.

37. A county town in Bazhou Prefecture, about ninety kilometers south of Yanjing; it was situated along the Juma River and suppliable by boat from the ocean. As is mentioned by Li Xinchuan, this town still remained under Jin dynasty control throughout the reign of Chinggis Khan; in fact it did not surrender to Mongol control until 1230.

38. In the Yuashi, the biographies of Yelü Chucai, Prince Tolui, and the imperial commissioner, Ta’achar, all discuss this incident. Ta’achar, of the Hüüshin surname, was an officer of the quiver-bearers (qorchi) in the imperial guard and a grandnephew of Boroghul (who had been one of Chinggis Khan’s “four steeds”). After the conquest of North China, Ta’achar was given new pasturelands at Guanshan Mountain in Inner Mongolia. See YS 146.3457, 115.2885, and 119.2952.

39. Öködei or Ögedei Khan (r. 1229–1241).

40. Ch. zhǎnglì 長吏. In Chinese, “clerk” was both a neutral term for any official who was not part of the regular, centrally appointed officialdom, and a derogatory name for those officials who had not received Confucian training, and hence were not Yelü Chucai’s “craftsman skilled in assembling [i.e., governing] the civilized world.” Since the officials of the Mongol Empire before Qubilai had neither a regular process of selection nor widespread Confucian training, they were all mere clerks in Confucian eyes. As we will see, these “senior clerks” actually included powerful officials like the Kitan Šimei Hiêmdêibu. He was far from a mere “clerk” and referring to him as such reflects Yelü Chucai (and Song Zizhen’s) Confucian professional pride rather than an accurate view of his actual power.

41. This official’s name is not securely identified, but he may be the same as the Tuqluq-Bekter who appears as a darughachi, or overseer, of the Yanjing area eleven years hence in late 1240; see Zhao and Yu [1330] 2020, 446.

42. A tael measured 1.4 ounces; 500,000 taels equaled 10,000 dìng or balish, the standard ingot of the empire. See the tables of weights and measures in Appendix §2.7 (p. 192).

43. The Chinese picul or dàn as a dry measure of grain was variously standardized at 1.9 bushels under the Song, and at 2.7 under the Yuan. It is unclear which measure is in use here.

44. “Confucians” (Ch. rúzhě 儒者) were officially recognized in the Mongol period, but as an administrative profession, not as the clergy of a religion like Buddhism or Daoism.

45. The Confucian classics consisted of two parts. The first was the Five Canons (Canon of Changes, Exalted Documents, The Canon of Odes, Records of Rituals, and Springs and Autumns Annals), said to have been composed or edited under the Zhou dynasty (founded in 1046 BC). The second comprised the works of Confucius (551–479 BC) and his disciples (particularly the Analects of Confucius, and the Mencius, by his disciple of that name). Thus, Confucian doctrines may be summed up as the teachings of the Zhou and Confucius.

46. Yelü Chucai is here quoting from the biography of Lu Jia in chapter 97 of the Shiji, the Records of the Grand Historian written by Sima Qian (ca. 190–145 BC) of the Former Han dynasty. When Lu Jia began to expound the Canon of Odes and the Exalted Documents, the “Supreme Founder” of the Han (Han Gaozu, r. 202–194 BC) began to shout:

“All I possess I have won on horseback! Why should I bother with the Odes and the Documents?”

“Your Majesty may have won it on horseback, but can you rule it on horseback?” asked Master Lu. “Kings Tang and Wu in ancient times won possession of the empire through the principle of revolt, but it was by the principle of obedience that they assured the continuance of their dynasties. To pay due attention to both civil and military matters is the way for a dynasty to achieve long life. In the past, King Fuchai of Wu and Zhi Bo, minister of Jin, both perished because they paid too much attention to military affairs. Qin [the dynasty just before the Han] entrusted its future solely to punishments and laws, without changing with the times, and thus eventually brought about the destruction of its ruling family. If after it had united the world under its rule, Qin had practiced benevolence and righteousness and modeled its ways upon the sages of antiquity, how would Your Majesty ever have been able to win possession of the empire?” The emperor grew embarrassed and uneasy.

See Sima Qian/Watson 1993, 226–27, with a few modifications for consistency.

47. In fact, this division of civil, military, and fiscal offices was not fully implemented until decades later under Qubilai Khan.

48. Šimei Hiêmdêibu was the son of one of the first Kitans to go over to Chinggis Khan’s cause, Šimei Ming’an. (See Zhao, “Memorandum,” p. 80 and n. 58; Peng and Xu, “Sketch,” p. 124.) The latter became the chief official in Yanjing after its fall to the Mongols in 1215, and he passed that authority onto his son Hiêmdêibu.

49. That is, Chinggis Khan’s younger brothers (the uncles of Öködei), who held important fiefs in North China and Manchuria.

50. At this point, “the Southern dynasty” refers to the Jin, who were still holding out in Henan. Only after the annihilation of the Jin in 1234 would “the South” begin to mean the Southern Song dynasty.

51. As is mentioned by Peng Daya and Xu Ting (“Sketch,” pp. 94–95), these were the three chief administrators in the Secretariat in Yanjing with roughly equal rank.

52. The county-seat name of modern Datong, in northern Shanxi. In the early Mongol era, it was also known as the Western Capital, or Xijing, from its Liao and Jin designation.

53. That is, in 1214–1215, when the Jin court fled to Henan, and Yanjing was taken by the Mongol armies.

54. Ch. jiǔ 酒. This would be a grain-based brew, similar to Japanese sake. See Zhao Gong’s “Memorandum,” p. 87 n. 54.

55. As may be seen from Peng Daya and Xu Ting’s account, the reality was rather more complicated.

56. Ch. dàn. A dàn was a measure of weight. For dry grain, a picul in the Yuan was roughly 76 kilograms or 95 liters under Mongol rule; 10,000 dàn thus equaled about 760 metric tons or over 25,000 bushels of grain.

57. Eunuch here is zhōnggùi 中貴, lit., “[one] honored in the central [palace].” However, Kümüs-Buqa (“silver bull”) is a Turkic name and there is no other reference to Turkic eunuchs in the Mongol court, so it is possible that here the term is to be taken literally as meaning simply an honored palace attendant and not as a eunuch.

58. “Common folk behind the mountains” refers to Han, that is, ethnic Chinese, civilians living in the Datong-Zhangjiakou area and the adjacent areas of Inner Mongolia; these areas were so-called because they were north of mountain ranges shielding Beijing to the northwest. The “people of our dynasty” are ethnic Mongols. The biography of Yelü Chucai in the Yuanshi adds that initially the emperor Öködei ordered that men from Yunzhong and Xuandezhou be chosen for these special households. It also notes that the cultivation of grapes was a still-recent import from “the West” (Xīyù), that is, the Middle East. See YS 146.3458.

59. Henan or “South of the (Yellow) River,” was the last redoubt of the Jin dynasty. It was conquered in 1232–1234 and its inhabitants deported north of the Yellow River. It is unclear if this exchange took place after Henan had already been conquered, or if Yelü Chucai is looking forward to the future disposition of the Henan people after they were conquered.

60. Silver mines in the mountains northwest of Beijing are mentioned by Marco Polo (2016, §74, 63) and in the Yuanshi, in the area of Yúnzhou: See YS 5.86, 16.335, 352–53, 18.391; Schurmann 1967, 149.

61. This sentence is excerpted from an eighteen-item memorial which Yelü Chucai had presented to Öködei. See YS 146.3457. Hexi people are the Tanguts of Western Xia.

62. Adding chūn 春, “spring,” following the text in Yuanchao mingchen shilue (Su 1996, 5.78).

63. This is modern Kaifeng, the Southern Capital of the Jurchen Jin dynasty.

64. The Wongian clan was the imperial family of the Jin dynasty.

65. Ch. Yansheng Gong. This title had been regularly granted to the most senior descendant of Confucius and the senior of his descendants clan living in Qufu (Shandong Province) since the Song dynasty in 1055. The title continued to be granted until 1935.

66. Present-day Linfen, in south-central Shanxi Province. It had been a center of high-quality printing of popular texts, especially drama, under the Jin dynasty; see Zhang 2014.

67. These offices are said to have primarily compiled histories and canonical texts; Ila (Yelü) Chucai staffed them with Confucians (YS 2.34). However, it is a testament to the power of Daoists at this time that the main project of the Pingyangfu office was actually an edition of the Daoist canon. See Wang 2014; Wang 2018, 74–77. “Civil administration” (Ch. wénzhì 文治) here could also be understood as “literary or cultural administration.”

68. These are the Longshan Mountains marking the border between present-day Shaanxi and Gansu Province. “West of the mountains” is thus present-day southern Gansu.

69. As always in Mongol-era texts, the West (Xīyù) here indicates Central Asia and the Middle East, i.e., all those sedentary kingdoms accessible to Chinese through caravan trade to the West.

70. As Matsuda Kōichi (2014) has shown, this estimate that almost half of the population of North China had been made prisoners of war to private commanders is confirmed in the surviving records of Dongpingfu in Shandong, where 113,000 households of “new civilians,” that is, former enslaved prisoners, were added into the 115,000 households of “old civilians.”

71. “The South” here refers to the Southern Song dynasty in South China, while the “West” refers to the Qipchaq, Ruthenian, and other Eastern European kingdoms.

72. Ch. zhǔ 屬.

73. The very formal phrasing here and the departure from narrative order in referring to Chinggis Khan’s legacy is rather unusual and suggests an apocryphal glorification of Chucai. It is notable that Su Tianjue, in excerpting the spirit-path stele for his own biography of Chucai, omits this passage. Perhaps he doubted its authenticity.

74. “Appanages for household expenses” is Chinese tāngmù yì 湯沐邑, lit., “town for hot bathing water.” This traditional phrase designates a district set aside for the private expenses of a member of the imperial family. See Hucker 1985, §6301; Farquhar 1981, 46 n. 167.