Ever wonder how hackers are able to get into a secure network and be in the network for months and sometimes years without being caught? Well, these are some of the big tricks for staying inside once you are there. Not only will we discuss maintaining access to a local machine you have owned, but also how to use a Dropbox inside a network, and have it phone home.

In this chapter, we will be covering the following topics:

- Using Netcat on a compromised Windows server

- Putting a shared folder into a compromised server

- Using Metasploit to set a malware agent

- Using a Dropbox to trace a network

- Defeating a NAC in two easy steps

- Creating a spear-phishing e-mail with the Social Engineering Toolkit

Persistent connections, in the hacker world, are called Phoning Home. Persistence gives the attacker the ability to leave a connection back to the attacking machine and have a full command line or desktop connection to the victim machine.

Why do this? Your network is normally protected by a firewall and the port connections to the internal machines are controlled by the firewall and not by the local machine. Sure, if you're in a box you could turn on telnet and you could access the telnet port from the local network. It is unlikely that you would be able to get to this port from the public network. Any local firewall may block this port, and a network scan would reveal that telnet is running on the victim machine. This would alert the target organization's Network Security team. So instead of having a port to call on the compromised server, it is safer and more effective to have your victim machine call out to your attacking machine.

In this chapter, we will use HTTPS reverse shells, for the most part. The reason for this is that you could have your compromised machine call to any port on your attacking machine, but a good IDS/IPS system could pick this connection up if it was sent out to an unusual destination, such as port 4444 on the attacking machine. Most IDS/IPS systems will whitelist outbound connections to HTTPS ports because system updates for most systems work over the HTTPS protocol. Your outbound connection to the attacking machine will look more like an update or regular user Internet browsing than an outbound hacked port.

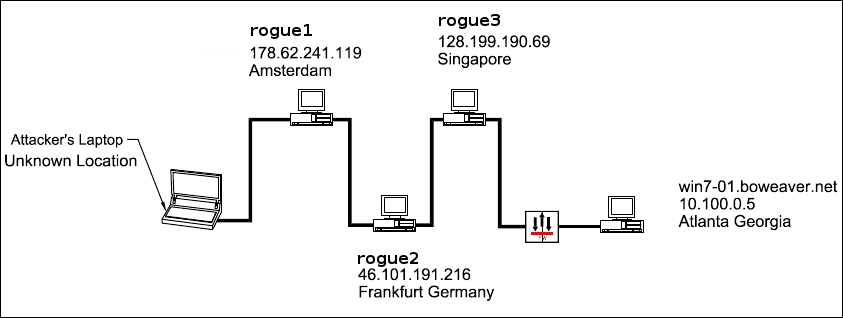

A persistent connection does have to go back directly to the attacker's machine. You can pivot this type of connection off of one or more machines to cover your tracks. Pivoting off one machine inside the target network, and a couple outside the target network, makes it more difficult for the defenders to see what is happening.

Yes, you can pivot this type of attack off of a machine in North Korea or China, and it will look like the attack is coming from there. Every time we hear in the media that a "cyber attack" is coming from some dastardly foreign attacker, we roll our eyes. There is no way to be sure of the original source of an attack, unless you have access to the attacking machine and its logs. Even with access to this attacking machine, you still don't know how many pivots the attacker made to get to that machine. You still don't know without a full back-trace to the last connection. Use something such as Tor in the process and there is no way anyone can be sure exactly where the hack came from.

In this demo, we will be doing an attack from a four-way pivot going across the world, and through four different countries to show you how this is done. Yes, we are doing this for real!

One problem with persistent connections is that they can be seen. One can never underestimate the careful eye of a paranoid sysadmin ("Why has server 192.168.202.4 had a HTTP connection to a Chinese IP address for 4 days?"). A real attacker will use this method to cover his tracks in case he gets caught and the attacking server is checked for evidence of the intruder. A good clearing of the logs after you back out of each machine, and tracing back the connection is almost impossible. This first box to which the persistent connection is made will be viewed as hostile in the eyes of the attacker and they will remove traces of connecting to this machine after each time they connect.

Notice in the following diagram that the victim machine has an internal address. Since the victim machine is calling out, we are bypassing the inbound protection of NAT and inbound firewall rules. The victim machine will be calling out to a server in Singapore. The attacker is interacting with the compromised machine in the US, but is pivoting through two hops before logging into the evil server in Singapore. We are only using four hops here for this demo, but you can use as many hops as you want. The more hops, the more confusing the back-trace. A good attacker will also mix up the hops the next time he comes in, changing his route and the IP address of the inbound connection:

For our first hop, we are going to Amsterdam 178.62.241.119! If we run whois we can see the following:

whois 178.62.241.119 inetnum: 178.62.128.0 - 178.62.255.255 netname: DIGITALOCEAN-AMS-5 descr: DigitalOcean Amsterdam country: NL admin-c: BU332-RIPE tech-c: BU332-RIPE status: ASSIGNED PA mnt-by: digitalocean mnt-lower: digitalocean mnt-routes: digitalocean created: 2014-05-01T16:43:59Z last-modified: 2014-05-01T16:43:59Z source: RIPE # Filtered

Tip

Hacker Tip

A good investigator, seeing this information, would just subpoena DigitalOcean to find out who was renting that IP when the victim phoned home, but it could just as likely be a machine belonging to a little old lady in Leningrad. The infrastructure of a BotNet is developed from a group of compromised boxes. This chapter describes a small do-it-yourself botnet.

We will now pivot to the host in Frankfurt Germany 46.101.191.216. Again, if we run whois, we can see the following:

whois 46.101.191.216 inetnum: 46.101.128.0 - 46.101.255.255 netname: EU-DIGITALOCEAN-DE1 descr: Digital Ocean, Inc. country: DE org: ORG-DOI2-RIPE admin-c: BU332-RIPE tech-c: BU332-RIPE status: ASSIGNED PA mnt-by: digitalocean mnt-lower: digitalocean mnt-routes: digitalocean mnt-domains: digitalocean created: 2015-06-03T01:15:35Z last-modified: 2015-06-03T01:15:35Z source: RIPE # Filtered

Now on to the pivot host in Singapore 128.199.190.69, and do a whois:

whois 128.199.190.69 inetnum: 128.199.0.0 - 128.199.255.255 netname: DOPI1 descr: DigitalOcean Cloud country: SG admin-c: BU332-RIPE tech-c: BU332-RIPE status: LEGACY mnt-by: digitalocean mnt-domains: digitalocean mnt-routes: digitalocean created: 2004-07-20T10:29:14Z last-modified: 2015-05-05T01:52:51Z source: RIPE # Filtered org: ORG-DOI2-RIPE

We are now set up to attack from Singapore. We are only a few miles from our target machine, but to the unsuspecting IT systems security administrator, it will appear that the attack is coming from half a world away.

If we have either root or sudo access to these machines, we can cleanly back out by running the following commands. This removes the traces of our login. Since this is our attacking machine, we will be running as root. The file that contains the login information for the SSH service is /var/log/auth.log. If we delete it and then make a new file, the logs of us logging in are now gone:

- Go into the

/var/logdirectory:cd /var/log - Delete the

auth.logfile:rm auth.log - Make a new empty file:

touch auth.log - Drop the terminal session:

exit

Now exit from the server and you're out clean. If you do this on every machine as you back out of your connections, then you can't be found. Since this is all text based, there isn't really any lag that you will notice when running commands through this many pivots. Also, all this traffic is encrypted by SSH, so no one can see what you are doing or where you are going.