CHAPTER 1

“I’m transgender.”

Growing up, the TV was always on in my house.

So it was fitting that the first time I heard the word “transgender,” I was ten years old and watching television.

The den on the second floor of our home was totally dark except for the light from Just Shoot Me!, a weekly television show about a women’s fashion magazine, when a guest character named Brandi—played by the beautiful Jenny McCarthy—appeared on the screen. Brandi had been the best friend of one of the show’s main characters, played by David Spade, in elementary school. But the story came with a twist: Spade had known Brandi only as a boy, but now here she was, a beautiful woman.

Cue the laugh track.

I turned to my mom, a warm and friendly woman around the age of fifty at the time, who was sitting across from me in a recliner. I gulped and asked her, “Can people really change their gender?”

I worried that even asking the question would raise questions about me. In the moments since Brandi’s twist was revealed, I had quickly convinced myself that this was a possibility that existed only in the world of television.

My mom responded nonchalantly, still focused on the show. “Yes, they’re called transgender. Or something like that.”

Oh my God, that’s me, I thought. The show wasn’t particularly disrespectful by the standards of late-1990s/early-2000s television, but the joke was clearly that Brandi, a transgender woman, was of even passing interest to other human beings. It was hilarious that people were attracted to her. The audience’s laughter built up every time someone commented on her looks, not knowing that she was really trans.

Representation in popular culture is key. It is often the first way many of us learn about different identities, cultures, and ideas. That evening’s episode had offered me the life-affirming revelation that there are other people like me and that there was a way for me to live my truth. But it did so in a way that made clear that, should I take that path, I’d be risking pretty much everything, from finding someone who would love me as me to being taken seriously by the broader world.

Ten-year-olds don’t know a lot, but they know that they don’t want to be a joke. Looking at my mom, that realization sank in. I’m going to have to tell her this someday, and she is going to be so disappointed.

Watching this sitcom wasn’t the beginning of this struggle for me. For as long as I can remember, I’ve known who I am. For the first ten years of my life, I didn’t know there was anything I could do about it or that there were other people like me, but I knew who I was. It wasn’t that I knew I was different. I knew, specifically, that I was a girl.

When the boys and girls would line up separately in kindergarten, I’d find myself longing to be in the other line. The rigid and binary gender lines are made abundantly clear to all of us at a young age, from the color-coded clothing to “boy’s toys” and “girl’s toys.” For a five-year-old, the distance between the two gendered lines in kindergarten might as well be a mile apart. It was clear: There was no crossing of the divide, under any circumstances.

I grew up on a picturesque block of large homes in west Wilmington, Delaware, a beautiful tree-lined street of three-story, symmetrical houses built in the 1920s. The neighborhood was filled with young families of lawyers, doctors, and accountants. The kids, all roughly my age, would meet every night for a game of tag or capture the flag. While it was the 1990s, the atmosphere could have been the 1950s. It could have been Leave It to Beaver.

Just across the street from us was the home of two girls, Courtney and Stephanie, a year younger and a year older than me. Their house became my escape. In the playroom, located away from all the parents, they’d let me put on their different Disney princess dresses. My favorite was a shiny blue Cinderella dress. Putting it on and looking down, I felt the longing go away. A completeness instantly came over me, and a dull pain that I didn’t fully understand was gone.

But every time, as I’d play in the Cinderella dress, the proverbial stroke of midnight would arrive. I’d have to take it off and return to playing the part that I’d already learned was more than just expected of me—it was “me” to everyone else in my life. I was playing an extended game of dress-up, a part society had thrust on me that, it seemed, I had no choice but to follow.

All of this was four or five years before I saw that sitcom with my mom. Convinced that there was no way out, I’d dream of the universe intervening. I’d lie in bed each night and pray that I’d wake up the next day and be myself, for my closet to be filled with dresses, and for my family to still love me and be proud of me.

By the time I had “officially” learned about transgender people at the age of ten, I’d already grown a deep interest in politics. As a young kid, I loved building blocks and constructing elaborate houses out of them. By six, I’d spend nights and weekends building detailed re-creations of the White House in my bedroom. Nerdy, I know.

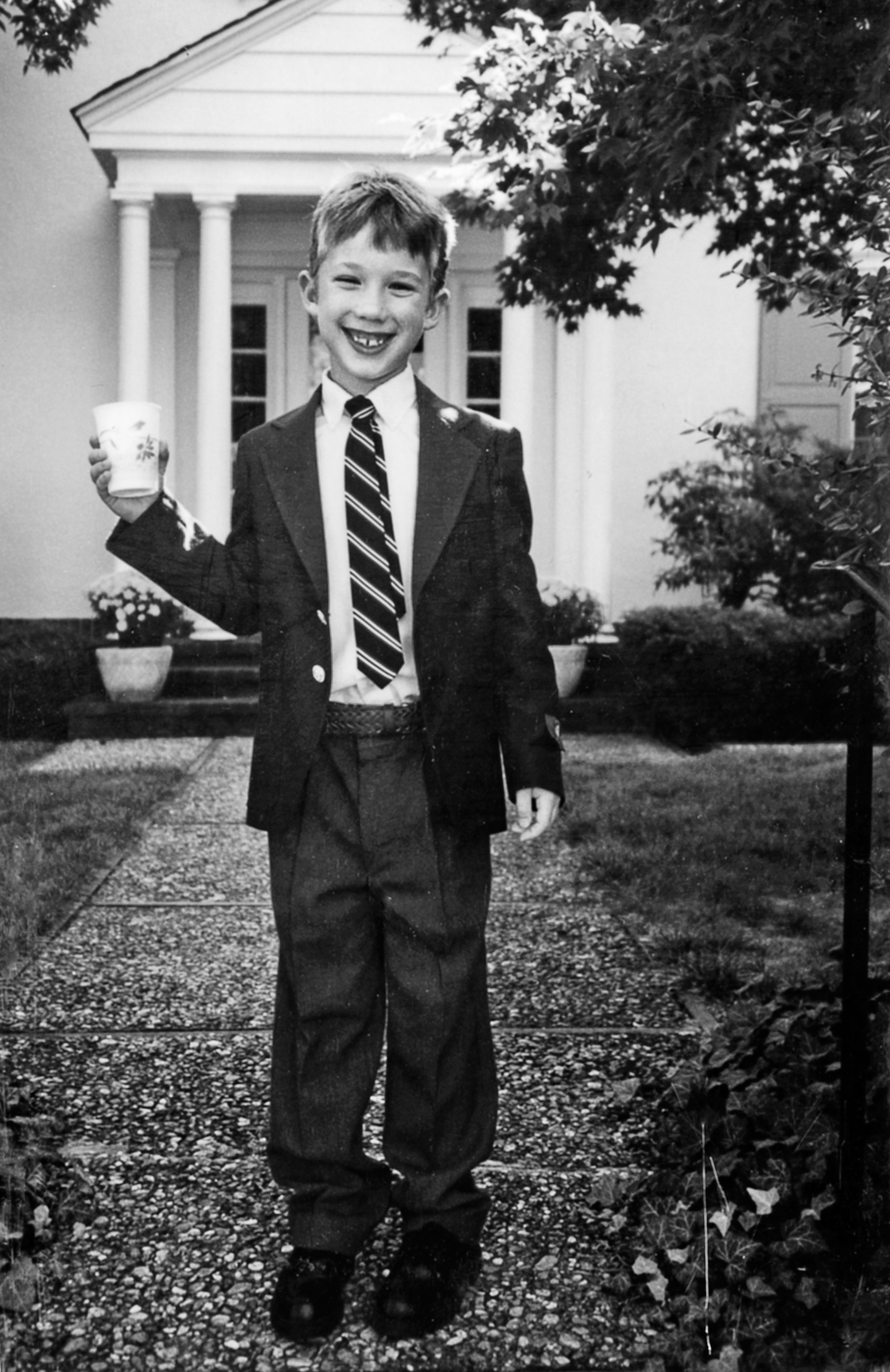

The first books I started to read were, naturally, about the building and the history within it. Soon, I was voraciously reading about the presidents and gaining a profound love of history. In elementary school, my teachers and other parents had already started calling me “the little president.”

Me, my endless smile, and the best blue-blazer imitation suit jacket a seven-year-old could muster.

As a young person first gaining a fuller perspective on the size of the world, the scope of the social change I read about fascinated me. I devoured books about Franklin Roosevelt, his New Deal, and World War II. I became obsessed with Lincoln.

But nothing inspired me more than the fights for equal rights at the center of our history. Each generation, it became clear, was defined by whether they expanded equality, welcoming and including people who had once been excluded or rejected.

And as I began to understand that there was something about me that society disapproved of, I became drawn not just to the history, but also to the possibility of politics as a means of fixing society. Of creating a world that was a little more loving and inclusive. Even if I couldn’t fix it for myself, I thought that fixing it for others could make my life worthwhile.

Being me appeared so impossible that changing the world seemed like the more realistic bet. And the thought of doing both at the same time was, in a word, incomprehensible. Something became abundantly clear to me as I read my history books: No one like me had ever made it very far. Or, at least, no one who had come out and lived their truth.

At an early age, I was very aware of just how lucky I was. As we drove across town to my elementary school, the privilege that my family enjoyed was clear. I knew just how fortunate I was to have the opportunities that I did, but I still felt alone. And more than anything else, I felt resigned to a life that required me to choose between who I am and the kind of life I hoped for.

Politics seemed, comparatively, so attainable and tangible. Growing up, I personally knew more U.S. senators than transgender people. With Delaware as small as it is, a state of less than a million people, we’d routinely see our elected officials at the grocery store or the gym. And to any young person remotely interested in politics in Delaware in the early 2000s, one man stood above the rest. At eleven years old, I met my political idol.

Joe Biden was a towering figure to me. Even before he was selected as Barack Obama’s running mate, he was the hometown kid who had made it big, the Delawarean who had become a national figure with presidential ambition and buzz. When I first met him at a local pizza shop while eating with my parents, I was star-struck. Here was the guy I had seen on the news—right in front of me.

He had just gotten off the Amtrak from D.C. and was meeting his wife, Jill, for dinner. They sat right next to our table. And knowing how much it would mean to me, my parents introduced me as he walked over.

I was speechless. I just stared up at him, barely able to introduce myself.

He kneeled down, ripped out his schedule for the day from his briefing book, and pulled out a pen.

“Remember me when you are president,” he wrote, followed by his signature.

I stared at the page for the remainder of dinner and, when we got home that night, promptly hung it in my bedroom next to my Little League trophies. The February 1, 2002, Joe Biden schedule became my prized possession as a kid.

And in early 2004 I got my first real taste of Delaware politics. My dad, a compassionate, intellectually curious, and hardworking attorney, told me that his colleague Matt Denn had decided to run for insurance commissioner, a statewide position charged with overseeing the insurance industry in Delaware that, for some reason, is elected in our state.

Perhaps doing my father a favor because he knew how much I loved politics, Matt graciously allowed me and my friends, some of whom were equally interested in politics, to travel around with him as he campaigned. Most of the time, we’d hand out campaign literature or make phone calls on his behalf, but since we had started developing a strong interest in film as well, we also trailed the candidate with a big video camera for a documentary on his race.

It was on the trail in 2004 that I met an elected official named Jack Markell. Jack was in his early forties and serving his second term as Delaware’s state treasurer. Prior to entering politics, Jack had been a successful businessman, helping to lead the cell-phone company Nextel and working as an executive at Comcast. In 1998, he dove into politics and was elected state treasurer. To an intimidated thirteen-year-old, he was one of the most approachable of the statewide politicians, almost always sporting a big, warm smile.

In a crowded lobby of a hotel hosting the state Democratic Party convention, my friends and I approached Jack and asked him for an interview for our documentary. Either because we sensed that he was going to run for higher office someday or because we didn’t know what we were doing (as much as I still wish it was the former, it was probably the latter), we started lobbing controversial policy questions at him that were totally unrelated to his role and our film: “What’s your position on marriage equality?” “Where do you stand on the death penalty?”

He probably thought, Who the hell are these kids and why are they asking me questions when I just sign the damn checks for the state? Either way, he was gracious, and at each campaign event that year he would always come up to us and seemed genuinely interested in how we were doing. He made an impression on me; he was an adult politician who cared about what I was doing and what I thought. Like the Joe Biden note, Jack made me feel like I mattered in politics, even though I was only thirteen.

I was excited when I learned that Jack was rumored to be considering running for governor in 2008, when the sitting governor would be term-limited. Before he could do that, though, Jack would need to win reelection as state treasurer in 2006. And when my parents hosted a small campaign event for him two years after we had first met, I had the chance to introduce the man who had become my friend on the trail.

After doing a good enough job with the speech at my parents’ house, Jack asked me to introduce him at an event where he would officially launch his reelection campaign as state treasurer. It was just fifty people in the back of a restaurant, but to my sixteen-year-old self, it felt like I had made the big time.

Soon, I was introducing Jack everywhere, beginning a three-year ride of opening for him at various events and functions as he sought and eventually won the governor’s office. Speaking as a fifteen-, sixteen-, seventeen-, and eventually eighteen-year-old about what Jack Markell meant to me, I would frequently say that “whenever I’m asked who my role models are, after my parents, but before presidents, I always say Jack Markell.”

After he announced his candidacy for governor in the spring of 2007, I went to work for his campaign, first as an intern and then, during the summer of 2008, as a field organizer, my first paid job in politics. I spent the lead-up to the primary organizing volunteers in the state representative district where I grew up, knocking on doors and registering voters. It was a tough race. Jack was the underdog as he battled it out with the heir apparent, the sitting lieutenant governor, John Carney.

Throughout the campaign, the speeches continued. At fund-raisers and campaign events across the state, I’d be Jack’s opening act, speaking about his intelligence, accomplishments, and, most of all, his heart. It was a routine that, following a monumental wave of door knocking, phone banks, canvass organizing, volunteer calls, and speeches, culminated in Jack and his wife, Carla, asking me to introduce him on primary night, effectively the general election in our deeply blue state.

The vast majority of elected officials had endorsed our opponent, and the party machine was out in force for its preferred candidate. But in the end Jack would triumph by fewer than two thousand votes. A close margin to be sure, but even winning an election by one vote feels like a massive victory.

It was one of the best nights of my life. I believed in Jack and he believed in me. Standing in front of a big blue curtain and before news cameras, reporters, and hundreds of cheering supporters, I introduced the soon-to-be-governor on the biggest night of his political life. It was surreal.

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen a presumptive governor introduced on his victory night by an eighteen-year-old,” observed a radio reporter covering the results as they carried my introduction live.

Jack and Carla had become like a second family to me. I was with them on Jack’s inauguration day in 2009, they would attend my high school graduation with my family in June, and that summer, just before I went off to college, I would travel around the state with Jack as his personal aide, the Charlie Young to his Jed Bartlet (for fans of The West Wing). I’d stay with them at the governor’s mansion, Woodburn, sometimes as a family friend and sometimes as a staffer.

He genuinely believed that I could be governor and would give me pointers along the way. He had already fulfilled his dream but was committed to lifting others up behind him. He gave me the confidence to think big and to fight for what I know is right.

If he was struggling with a speech, he’d call me into his ornate office, step out from behind his desk, and motion for me to sit at it.

“I don’t know what to say here,” he’d instruct me. “Would you mind giving it a try?”

He’d walk out of the room to go to another meeting, leaving me sitting at the governor’s desk to finish his speech, an overwhelming assignment for an eighteen-year-old kid. He’d frequently say things to me like “when this is your desk,” “when this is your home,” “when you’re governor.” Jack made me believe that my dreams were possible. But I still knew there was a trade-off. I had known it since childhood: I needed to hide and conform. I feared that if I deviated from the norm too much, my world would come crashing down.

But I never let that impact my values. I tried to be an ally to the LGBTQ community when so many think that the only way to prove they aren’t queer is with bullying and machismo. Outwardly, I presented as a straight, cisgender—the term for people who are not transgender—boy. I dated girls throughout high school and the first part of college. I had short hair and wore traditional masculine clothing. I did all of this out of a sense of obligation that I needed to play the part that others assigned to me. I just didn’t want to let anyone down. And I didn’t want to let myself down.

While I appeared happy to everyone else, perpetually sporting a large smile I had become known for, I continued to carry with me the struggle of that five-year-old in her neighbor’s Cinderella dress. And just as I had done as a young kid, every night as a teenager I would hope and pray that I would wake up the next day as myself.

Unable to go over to friends’ houses and play “dress-up” anymore, I’d find any excuse to wear a dress or makeup. I attended an arts middle and high school, where I focused on cinema studies. Films were an escape. They allowed me to develop plots where I would play a girl.

But they weren’t the only outlet. Halloween was one of the few opportunities when it became remotely socially acceptable for me to express myself. So while every other kid was going out as someone or something else, it was one of the few opportunities that I had the chance to go out as me. Nothing fancy. In fact, pretty boring: jeans, a cute top, and a cheap wig I’d purchase at a costume store.

It wasn’t until I got a computer of my own in middle school that I opened a window into trans lives. I learned that transgender people have existed throughout time and cultures. We didn’t always use the same words to describe them, but there they were transgressing gender lines.

I read about the six gender identities that existed in ancient Jewish culture, including Saris, a person who was assigned male at birth but developed female characteristics later in life, either biologically or through human intervention. I found out that many Native American cultures affirmed and celebrated individuals they called Two-Spirit.

I learned about the diversity of the trans community. That it does not just include trans women and trans men, but also gender nonconforming, genderqueer, or gender-expansive people. Gender identities beyond the binary of men and women have existed and, in many cases, have been rightly celebrated throughout cultures.

I learned about our history. I came across the story of Lili Elbe, one of the first trans women to undergo gender affirmation surgery, whose story was told in the book and film The Danish Girl. Europe in the 1920s saw pioneering efforts in expanding the culture’s understanding of sexuality and gender, progress largely wiped out with the Nazis’ rise to power in Germany. I read articles from newspapers in the fifties about Christine Jorgensen, the “blond GI bombshell.”

And I first learned the names Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, the transgender women of color who threw the first bricks launching riots protesting anti-LGBTQ police violence in New York City at a bar called the Stonewall Inn. That uprising, known as the Stonewall Riots, helped launch the modern movement for LGBTQ rights and dignity.

Late at night, I’d hop online and read about our identities. I’d look at pictures of those who had come out. I’d surf the Myspace and, later, Facebook pages of everyday trans people. I’d read their stories and find that many of the things they wrote about were things I was feeling or experiencing in my own life.

I knew who I was, but I still couldn’t fully accept it. I’d stand in my bathroom, staring at myself in the mirror, just daring myself to say it out loud.

Say it. Say it. Say it. Say it. You know it’s true, I’d think to myself.

“I’m transgender,” I’d finally say into my mirror. “I’m a girl.”

Instantly, shame would run over me. It couldn’t be true. Incapable of accepting that fact, I kept trying to convince myself that it would diminish with age. Or, at the very least, that I could compensate for it. At eighteen and nineteen, I’d still try to convince myself with the same arguments I made ten years earlier.

Maybe I don’t have to live my truth if I can spend my life making the world a little fairer, if I can have a hand in making more space for other people—and future generations—to live their lives more fully.

With the support of people like Jack Markell and others, this goal seemed within reach. At the very least, it certainly seemed possible.

But with each professional advancement, I carried with me the sinking feeling I felt when I first learned, sitting with my mom, the word “transgender.” Each step forward increased the disappointment that I knew I’d be if—and, really, when—I’d come out.

I worried about disappointing people like Jack, who had invested so much time and energy in mentoring me. But most of all, I feared disappointing my parents.

I lucked out in the parent lottery. My mom, Sally, is a former guidance counselor turned stay-at-home mom, or as she refers to herself, a domestic engineer. My dad is a former antiwar protester turned corporate attorney in the capital of corporate law: Delaware. They had me eight and ten years after my brothers, Sean and Dan, and are the type of warm, generous, and intelligent parents that friends frequently adopt as their own surrogate family.

I never once heard my parents disparage a person for who they were, and I watched them seamlessly and lovingly greet the news that my brother Sean is gay with compassion and unending support.

“We all just want Sean to be happy and healthy,” my parents told me when Sean sat me down in eighth grade to tell me he was dating Blake, the man who would eventually become his husband.

But even for my progressive parents, I feared my news would be too much. After all, at that point, it was still too much for me.

I also knew that if I confided in anyone, it would force me to admit it fully to myself, and I wasn’t ready for that. So I kept it inside, as best I could. Increasingly, it was something I thought about every single waking hour of every single day.

In 2009, I moved down to Washington, D.C., to continue pursuing politics. I started at American University, a college consistently ranked one of the most, if not the most, politically active in the country.

During my sophomore year, after serving in the Student Senate, I decided, at the urging of the sitting student body president, to run for president of the AU student government. So I ran. And I ran hard. At our hyperpolitical campus, it was a coveted position.

I became the first candidate for student body president to knock on every single door in every single residence hall on the main campus: thousands of doors. I worked night and day and, in the end, won by about ten percentage points in a four-person field—a decent margin, given the number of people in the race.

It was the first time I had tested my skills outside Delaware—and outside of Jack’s mentorship. I promised my parents that I would call them the moment I found out the results, which were expected to be in at about eight p.m. on a Wednesday night. I was delayed in calling them due to celebrations in the dining hall and interviews with campus media.

“Mom! Dad! I won!” I yelled into the phone when they picked up.

Ever the crier, my mom broke down and said, “Why did it take so long for you to call?! We were convinced you had lost!”

They were ecstatic when they got the news, and shortly after getting off the phone with them, I got a call from Jack.

“You kicked ass,” he said, clearly having checked the results online. Jack and I had frequently talked about his own run for student body president at Brown University, which he lost. Fifth place out of five candidates.

“Thank you, but winning your student government race is a bad omen for things to come,” I said, reminding him of his, and Bill Clinton’s, early losses in college campaigns.

He laughed and shot back, “Well, I have a feeling you’ll turn out differently than the folks who beat us.”

To my surprise, the role was a full-time job and then some. It was a job you could never escape. Sitting in class on the first day of school during my term, everyone’s heads would turn when the professor called out my name on the roster. People, particularly freshmen, would explode with excitement if they had a drink next to me at a party. I was a “campus celebrity,” as my friends would mockingly say.

At the start, I thought I would enjoy that part, but it got old quickly. The introvert in me enjoyed my anonymity, and even the coolest parts still felt like I was living someone else’s life.

The theme of my term continued my long-standing passion for inclusion and equality that I had developed as a precocious reader of history. Everything I did was about “making AU as inclusive, accessible, and open as possible.” Every initiative, every policy, every speech fell within that theme, including our robust work on LGBTQ equality.

It was through this work that I gained my first experience in trans-specific advocacy by offering the student government’s support to a Transgender Day of Remembrance event, a commemoration of those who had lost their lives throughout the previous year. Beyond the 41 percent of transgender people who report attempting suicide are the countless, and often unknown, individuals who take their own lives, as well as the dozens in the United States who lose their lives to violence committed at the hands of someone else.

I worked with the school administration to secure gender-inclusive housing, which would allow students of all gender identities to room with the student or students of their choice. The old policy, automatic segregation based on someone’s legal gender, was rooted in the assumption that two people of different genders could never comfortably live together and that doing so would inevitably lead to attraction and, potentially, drama.

That policy, however, completely erases the reality of gay students and harkens back to a period when men and women could never just be friends. It also limited options for students who were transgender but had not yet legally changed their gender. With surprising support from the school administration, we succeeded in expanding options and creating more choice for students.

The substance of the job felt good. From big-scale issues like combating sexual assault to smaller quality-of-life issues like the construction of speed bumps in highly foot-trafficked parts of campus, getting things done and making life a little easier for others was truly just as professionally fulfilling as I imagined. But even that satisfaction could not distract me from my identity. And I finally became convinced that the reasons I used to rationalize staying in the closet wouldn’t actually bring me the wholeness I hoped for. It was becoming clear that as rewarding as making a difference in my community was, it wouldn’t compensate for a life in the closet. Far from it.

One day, while I was sitting in the office of our friendly director of student housing, he asked me where my passion for LGBTQ equality came from. I had been pushing gender-inclusive housing pretty hard, and people were curious where the interest originated. After all, at that point, I identified as your typical straight boy. Everyone, including straight, cisgender people, should be able to care about LGBTQ equality without others questioning their motivation, but I knew the director of student housing understood that. He was letting me know that others were curious.

“Well, it’s the right thing, for one. But I think personally…” I paused. I wanted to say it. I wanted to say, “because I’m transgender.”

But I couldn’t.

“One of my brothers is gay,” I told him. “And I want to make sure people like my brother have the same opportunities to feel safe and welcomed as every other student.”

The answer was half true, of course, but it was the closest I had ever gotten to confiding in someone.

I left his office feeling like I was about to explode. By now, I had gone from thinking about my gender identity every hour to thinking about it every single minute. I could no longer compartmentalize. The only way I could get through anything was to imagine myself redoing it as a girl. Even the simplest action, like walking between classes, became unbearable unless I relived it in my own head, imagining a life that resembled my own but with one big difference: I was myself.

But even then, I was increasingly miserable. I’d still put on the smile I’d become known for, but it wasn’t really there. I was lost. My aspirations had been my distraction for so long, but they no longer provided me with the hope that things would get better.

And so I gave up on them. I gave up on politics. I was so exhausted by my own internal struggle that it was clear I wouldn’t have the strength for it. The tension between my dreams and my identity had always resulted in my dreams winning out.

But that wasn’t the case anymore. The pain had become too much. But in a twisted way, giving up allowed me to begin to come to terms with my identity.

Sitting in a biology class one day, I started to GChat one of my best friends, Helen, who was studying abroad in South Africa at the time. I had become close friends with her in high school. We worked on Jack Markell’s campaign together and started Delaware’s high school Young Democrats chapter. A year after she went on to American University, I followed suit. Helen is a social activist to her core, someone our friends describe as a walking bleeding heart.

Somehow, with her in South Africa, confiding in her felt a little less real, the distance amplified by an impersonal computer screen. I told her, in a series of online conversations, that I was struggling with my gender identity, that I thought I might be transgender, and that I wasn’t sure if I wanted to transition but that I had been thinking about it more and more.

Helen was nothing but supportive. She affirmed me at every step, and when I made the request that she try calling me by a different name and female pronouns, she obliged. Even in just telling Helen, I began to feel a little better.

Had she responded in any other way, I might have been scared back into the closet, confirmed in my suspicion that my world would come crashing down. Instead, her love and support made the impossible finally seem possible.

Maybe my world won’t fall apart.

A month later, while on winter break, Helen and I sat in my parents’ living room. The room was decked out for Christmas, my family’s favorite holiday. My mom has perfected the excessive holiday decorations that fall just on the funky side of tacky. Over hot chocolate, curled up on an oversized chair by our fireplace, I told Helen, “I think it’s only a matter of time before I come out as transgender.”

Baby step by baby step, I was slowly going from hiding, to confiding, to accepting. I was still frightened. I didn’t know how people would react. I feared I would be giving up the possibility of finding love—the first thing I learned about trans people was that loving us was a joke. But even with that fear, I could start to admit the reality and inevitability of my identity.

Two days later, on Christmas Eve, I sat next to my parents at a candlelight service in the beautiful stone sanctuary of our longtime Presbyterian church. The choir was singing “O Holy Night,” one of my favorite Christmas hymns. And as I stared at the stained-glass window on the final night of Epiphany, I had my own realization.

I can’t do this anymore. I cannot continue to miss this beauty. My life is passing me by, and I am done wasting it as someone I am not.

I took my cell phone out of my pocket and texted Helen. “I’m transgender and I’m going to tell my parents after Christmas.”

I tossed and turned that night, unable to sleep because I knew I would be shattering my parents’ sense of comfort and security for my future in just a matter of days.

Christmas morning started like all previous Christmases. I woke up and descended the stairs to see my parents ready for my brother Dan and me to open our presents. My oldest brother, Sean, was up in New York with his husband, Blake, for the holiday.

As the youngest, I usually got to open a present first, probably a vestige of my days as an impatient little kid in our family of five. This year was no different.

With my parents watching, I unwrapped what I knew was going to be clothes. I opened the box, and there, just as I had initially asked for, was a button-down shirt and a tie. As if I needed another reminder. As if I wasn’t nervous enough.

The shirt and tie felt like a symbol of the stark contrast between where I was and where I wanted to be, between how I was perceived and who I knew I was, and between my parents’ hopes for the future—a happy, successful child—and what I knew they would fear with my news: rejection. Rejection by friends, by neighbors, and, most certainly, by jobs.

I finished opening presents and retreated upstairs to my bedroom. About thirty minutes later, my mom walked in and sat on the edge of my bed. She’s an incredibly empathetic person and could sense something was off.

“What’s wrong? You’ve seemed down, and you never seem down,” she asked me.

“It’s nothing. I’m just overwhelmed at school,” I responded.

I could tell she didn’t believe me, but she didn’t press the subject. She left and went back downstairs to begin preparing the stuffing for our traditional Christmas dinner.

She just asked you. You have the courage to say it right now. Just do it.

I walked downstairs and into the small sitting room, where my mom was waiting for the oven to preheat. I sat down on the other end of our large, overstuffed couch and took a very deep breath.

There was no turning back at this point. I knew that once I told them, they would ask every question and latch onto any glimmer of hope that I was mistaken. I needed to present a completely even-keeled, thoughtful, and determined certainty. I had to be as firm in my resolve to them as I was in my knowledge of who I am.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about my sexual orientation and gender identity,” I began, throwing in “sexual orientation” because I knew she wouldn’t have the slightest idea what gender identity meant, and I wanted her to know that I was about to come out as something. “And I’ve come to the conclusion that I’m transgender.”

I paused, and she put her hand up to her now-shocked face. Through her fingers and already on the verge of tears, she asked, “So you want to be a girl?”

I was prepared for them to use inaccurate terminology and phrasing. I didn’t want to be a girl. I was a girl. And I wanted to be seen as me. But now wasn’t the time for those types of clarifications.

“Yes,” I said as confidently as I could, knowing that I had just destroyed so much of her world.

She burst into tears. “I can’t handle this! I can’t handle this!” she started screaming. “I need your dad!”

She ran up to my father’s third-floor study, where my dad and my brother Dan had gathered to set up his new TV. I chased after her and could see my dad’s confusion and fear as she came in bawling.

“Go ahead! Tell him what you just told me!”

I repeated the same sentence to him that I had said to my mom. My dad, sitting in his desk chair, put his arms on his head and let out a long sigh of disbelief.

I stared down at the carpet, waiting for his response. He sat there for another few seconds, thinking. I knew I needed to remain calm, almost like a therapist who was helping them through their emotional processing.

Dan, a slender state prosecutor with dark hair and a closely trimmed beard, broke the silence. “Well, I have an announcement, too. I’m heterosexual,” he jokingly declared, referencing the fact that he was now the only one of the three kids who was not LGBTQ.

As my parents continued to take in my announcement, Dan cut through the silence once again: “I always thought you were gay, but I guess this makes sense.”

I chuckled, but I’m not sure the comment registered with my parents. Seeing my mom uncontrollably sad and confused, my dad went into calm-attorney mode and began asking questions.

Obviously the first ten questions were some version of “Are you sure?”

The answer to that question was simple.

“I’ve never been more certain about anything in my life. I know this as much as I know that I love you two.” After all, I had spent my whole life thinking about it.

“I feel like my life is over. I feel like you are dying,” my mom repeatedly cried.

I had read during my years of research online that my parents would likely feel this way. After all, I was telling them that someone they loved might soon look very different, and they must have felt as if the life they’d imagined for their child was in peril. I’d never find a partner. I’d never find a job. I’d never be welcomed back in our home state.

“I’m still the same person with the same interests, intelligence, sense of humor, and the same smile,” I said, referencing my nearly constant trademark expression.

My dad asked about hormones. Not the hormone I was hoping to start taking, estrogen, but rather testosterone. What if they pumped me with testosterone, he asked, searching for a solution.

I assured him that would, frankly, make matters much worse.

As the questions went on, it became clear that my parents were struggling with the same empathy gap that I later would realize was one of the main barriers to trans equality among progressive voters: They couldn’t wrap their minds around how it might feel to have a gender identity that differs from one’s assigned sex at birth.

With sexual orientation it’s a bit easier. Most people can extrapolate from their own experiences with love and lust, but they don’t have an analogous experience with being transgender.

“The best way I can describe it for myself,” I told them, “is a constant feeling of homesickness. An unwavering ache in the pit of my stomach that only goes away when I can be seen and affirmed in the gender I’ve always felt myself to be. And unlike homesickness with location, which eventually diminishes as you get used to the new home, this homesickness only grows with time and separation.”

My dad, a longtime progressive, also said that he didn’t understand how one could feel like something that is a social construct. Wasn’t gender, and all the things associated with it, just a creation of society? Wasn’t that what feminism had taught us?

I explained to him that, for me, gender is a lot like language. Language, too, is a social construct, but one that expresses very real things. The word “happiness” was created by humans, but that doesn’t diminish the fact that happiness is a very real feeling. People can have a deeply held sense of their own gender even if the descriptions, characteristics, attributes, and expressions of that gender are made up by society.

And just as with happiness—for which there are varying words, expressions, and actions that demonstrate that same feeling—gender can have an infinite number of expressions. We can respect that people can have a very real gender identity while also acknowledging that gender is fluid and that gender-based stereotypes are not an accurate representation of the rich diversity within any gender identity.

All of these answers helped them intellectualize my news but did little to assuage their fears. What would come of my future? The only reference point my parents had for transgender people were punch lines in comedies or dead bodies in dramas. They had no references for success, something that had provided them significant comfort when my brother came out as gay.

After I went back down to my bedroom, my dad did what I had done for years: He Googled “transgender.”

Over the course of his research, he came across the report that had become all too familiar to me, “Injustice at Every Turn.” He saw the discrimination and violence faced by the community.

And then there was the suicide number. Forty-one percent of transgender respondents had reported attempting suicide in their lives. Forty-one percent.

I had never worried that I would be rejected by my parents or kicked out of the house. Like a lot of children, my biggest fear was much simpler. I didn’t want to disappoint them. Statistically speaking, that made me very lucky.

While 41 percent of transgender people had attempted suicide, that number dropped by half when the transgender person was supported by their family. And it dropped even further when they were also embraced by their community. My parents made clear from the start that they would support me, but “Injustice at Every Turn” reinforced just how important that support would be in their child’s life.

I awoke the next day at seven a.m. to my parents opening my door. As soon as I opened my eyes and saw them, I could tell that neither had slept, and that the crying, which had subsided by evening, had returned. This time, though, both of them were sobbing.

My parents walked to either side of my bed and got in with me, still crying. They both held me and pleaded again and again: “Please don’t do this. Please don’t do this. Please don’t do this.”

I let them cry and tried to tell them that it would be okay, but I couldn’t provide them with the response they hoped for. I hated to see my parents cry. Nothing I had ever done had caused them so much pain, and it ate at me to know that my life was making their lives harder. But there wasn’t a choice here, and I knew the alternative was far worse for all of us. I knew I had made the right choice. The only choice.

But for the next few days, I witnessed my parents mourn the “death” of their son, alternating between the different stages of grief, as my mom stared at pictures of me as a child. It was surreal, and all I could do was continue to tell them I wasn’t going anywhere. I told them over and over again that they were keeping me, while gaining a daughter.

But it took my oldest brother, Sean, ten years my senior, to put things into perspective for them.

Sean had called to wish us a merry Christmas, and when my mom told him my news, he hopped in the car with his husband and made his way straight down to Delaware, frantically searching everything and anything about “transgender” along the way. Sean was always a calm voice of reason in our family and, as an openly gay man, felt like an ally in the back-and-forth with my parents.

Sitting downstairs with my mom, Sean took some of the load off me and answered some of their questions. I think he also knew that my news was so shocking that having a second person to validate what I had said would help my parents digest the reality of the situation.

“What are the chances? I mean, what are the chances I have both a gay son and a transgender child?” my mom asked Sean.

“Mom, what are the chances a parent finds out that their child has terminal cancer?” Sean, a radiation oncologist, replied. “Your child isn’t going anywhere. No one is dying.”

It was the response she needed. She needed someone to push back and not feel sorry for her. She needed someone to put things into perspective.

Soon enough, I hoped we would all come to the place where she could ask that same question, “What are the chances?,” out of awe and not out of self-pity—a place where my parents could see that they had raised children who were confident and strong enough to live their truths and whose different perspectives enhanced our family’s beauty.

But that was for another day. This was a start, and I considered myself very fortunate.