A MEMORY IS what is left behind when something happens and does not completely unhappen. This trace does not have to be in a special place, and it does not have to tell much about what has happened.

If you walk through a swing door and it swings to behind you there is no memory of what has happened. If you walk through an ordinary door and leave it open behind you then the open door is a memory of your passage. The door is not the same as it was before – as other people in the room will be quick to point out.

If a dog walks across the carpet and out of the room there is no memory of its presence except to sensitive nostrils. If the dog had had muddy paws then the memory-trace would be more obvious.

It may be that in Indian restaurants the plates are made deliberately small in order to make the portions seem bigger, or it may be that the portions really are big, for you do not have to be a particularly messy eater to leave curry stains on the table-cloth. The curry stains are a memory. Anything that remains after the action causing it has ceased is a memory of the action.

The curry stains on the table-cloth are an example of the most familiar form of memory, that is, marks upon a surface. Writing, drawing or photographs are all instances of this type of memory-trace.

From a door which has been left open, from muddy marks on the carpet, from curry stains on the table-cloth, one cannot tell much about what has happened. The door may have been opened by the wind. The marks on the carpet may have been made by a cat or may even be a modern interior-decorating joke. The curry stains may have been made by a chimpanzee. This does not stop the open door, the muddy marks and the curry stains from being memories, for a memory does not have to be particularly informative about what has caused it. The interpretation or read-back of the memory may be difficult, misleading or even impossible. But as long as there is something to try and read back then there is a memory.

A photograph is an arrangement of silver particles on a piece of paper. The arrangement forms a memory of whatever was photographed. Usually a photograph is a good memory-trace and is not difficult to interpret. Even so, the interpretation of photographs does require experience. If photographs are shown to primitive people who have never seen any pictorial representation, then they are quite unable to make anything of the blobs of light and shade that make up a photograph.

A perfect memory-trace is one which requires no effort of interpretation at all. This is because the memory actually recreates the event which caused it. A good example is the recording of sounds. This recording process converts patterns in time into patterns in space. Patterns in time would be impossible to store; patterns in space are very easy to store. Apart from the pattern, there is no physical resemblance between a sound and the arrangement of tiny bumps on a plastic disc or the distribution of magnetization along a tape. Yet a gramophone or a tape-recorder will convert these arrangements back into the actual sound that produced them. No memory system could be more perfect.

When one is short of perfection one is guessing at what might have happened from what has been left behind. With a reasonable photograph one does not have to be very good at guessing. With the open door, the muddy marks on the carpet, the curry stains on the table-cloth, one has to guess rather harder.

Experience makes guessing easier, and so do other clues. Your knowledge of the door catch and its usual behaviour would probably exclude the likelihood of its having been opened by the wind. Your knowledge of restaurants and the scarcity of chimpanzees would make you guess that it was more likely to have been a person eating the curry even if the table-manners were not all that different. The muddy stains on the carpet arranged in certain groupings would suggest an animal. If you were to find another sort of mess in the corner the interpretation of the marks would be that much easier. And if you had some experience in tracking you might be able to distinguish a cat’s prints from a dog’s. In each case, things quite apart from the memory-trace itself make it easier and easier to read back.

Thus a memory-trace does not have to be particularly informative in itself in order to be useful. It may be useless on its own, but very useful when fitted into a general picture – as the great detective writers show all the time. It is enough that a memory is what is left behind when something happens and does not completely unhappen.

One usually thinks of memories as being recorded on blank sheets, just as a fresh piece of film is used for a new photograph. That sort of memory is easy to notice. But a memory may only alter something that is going on anyway.

A painter is painting a portrait. His child jogs his elbow. What happens on the canvas is a memory of that jog. The result may be an obvious squiggle or it may be no more than an alteration in the shape of one of the ears in the portrait. It would be easy to notice the squiggle and try and interpret it. The alteration in the shape of the ear is just as real a memory but much more difficult to interpret. Yet most memories are modifications in a process that is going on already rather than marks set apart by themselves.

Another sort of memory is even less obvious. One does not always expect a memory to play back the events of which it is a record, but one does expect a memory to give some indication of these events. There are, however, memories which do not have a tangible form that can be examined. Such memories simply make it easier for something that has happened to happen again.

If you were to dislocate your shoulder there might be nothing to show for it after it had healed up. Nor would an X-ray show anything. Nevertheless, it would be slightly easier for the shoulder to be dislocated again. A second dislocation would make a third one more likely, and so on. Memory of the dislocations would accumulate as an increasing tendency to dislocation until in the end you might have to have an operation which would really put it right. This facilitating effect is a hidden memory which is not manifest as itself but only as a tendency for something that has happened to happen again.

In a way this facilitating memory is an active memory, for instead of just being a passive indication of what has happened it actually helps to re-create the event.

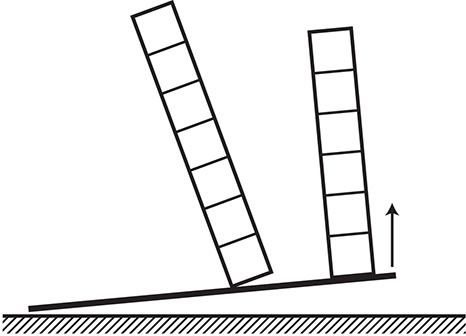

A simple model of this type of memory can be made with children’s building blocks of the plastic snap-together variety. Some of these blocks are fitted together to make small columns which are stood on a board as shown in the picture here. If you gradually tilt the board by lifting up one end then there will come a point when one or more of the columns will topple over. Since this is an artificial model one can now add an artificial rule of behaviour. This special rule decrees that each time a column topples over another block is added on to that column to make it taller. The columns are then stood up again and the tilting repeated. This time some of the columns are taller than the others and it is these taller columns which will topple over first. So you add more blocks to these columns and that makes them taller still and even more likely to topple over. The short columns, on the other hand, get less and less chance to topple over, for the tall columns now topple over when the board has hardly been tilted at all. According to the rules of this model, something that happens makes it easier for that thing to happen again. There are other very interesting principles illustrated in this model, but they will be discussed later.

Fig. 7

If you eat a sticky bun, your fingers remain sticky after you have finished eating. That is a short-lasting memory of the bun. Your appetite may be satisfied for some hours. That is a longer-lasting memory. Your gain in weight may be all too permanent.

A short-term memory is but a small extension of an event along the dimension of time. Yet even this small extension may be useful if it allows the interaction between two things which would otherwise have been quite separate.

Footprints in the sand on the edge of the sea fade pretty quickly. If you were late for a holiday rendezvous on the beach and when you got there the beach was empty, you would not be able to tell whether the girl had come and gone or never come at all. But if there were footprints on the sand by the edge of the sea then you would know, and perhaps even how long she had waited. A summer tan is another short-term memory that fades all too quickly. Even so, a girl returning from holiday beautiful with tan may attract the attention of an admirer who becomes a long-term event. A short-term memory is just a way of extending the influence of an event beyond the real time of its occurrence.

What we really require of a memory-trace is that it should tell us what happened, what caused it. Where possible, we actually force the memory-trace to re-create the event of which it is a memory. We attack the gramophone record with the pick-up head in order to make it re-create for our amusement the sounds that it holds as a memory arranged in patterns of plastic bumps. It is a selfish need on our part because we are standing outside the record.

If the gramophone record had a soul and consciousness it would not bother about playing out the music. The pattern of bumps would itself re-create the music without any need to play it out. The soul of the record would only become conscious of the music as the bumps formed in the first place. This would be its sole reaction to the music. Once the bumps had been formed, then going over them again would re-create the music, and the record could mutter to itself, ‘Ah yes, this is Beethoven’s Fifth’, or, ‘This is the Beatles’, as it recognized the different pattern of bumps. But because we have no regard for the ‘consciousness’ of the record we use it as a passive source of our pleasure.

A friend who has come back from an interesting trip abroad is pumped with questions and required to play back the experiences for our benefit. As far as the friend is concerned his memory of the events does not depend on the sound he makes when he talks about them.

If a table-cloth were a consciousness surface then the curry stains would be that table-cloth’s way of being aware of what was happening above it. It would be a limited sort of consciousness, capable of only a few perceptions: nothing happening, small curry stains, large curry stains, curry stains in several different areas. Yet the pattern would be repeatable. Whenever a curry stain appeared on the table-cloth its consciousness would recognize a curry-stain-producing situation. If a fake curry stain were produced then the table-cloth would mistakenly identify the situation as a curry-stain-producing one.

Memories constitute their own consciousness and their own perception. There is no need to play back to something outside of themselves.

A blind man may know that a certain person is in the room by the sound of that person’s voice. If that same pattern of sound could be produced in another way (for instance by a very good tape-recorder) then the blind man would know that the person was in the room even when he was not. He would not just think it but actually know it, since what he received would be the same in each case.

The total reaction of a photographic plate to a camel which is photographed onto it is the pattern of light and shade upon its surface. If exactly the same pattern could be produced in some other way than by having a camel present, then as far as the plate was concerned there would be no difference. If the appropriate pattern of light and shade were copied from another photograph, the plate would still have the complete camel experience. If the pattern on the plate gradually changed from some other image to the camel image, then the plate would suddenly come to have the camel experience.

If an event causes a particular pattern to form on a memory-surface, then reactivation of that same pattern will re-create the event as far as the memory-surface is concerned. One can forget about the need for play-back and the need for some outside agent to make use of what is on a memory-surface.

Different memories are different patterns left behind by different things. If one wants to be able to recognize the different things, then the memory-traces must be kept separate from each other in such a way that they can be made use of on their own. What sort of system would one need in order to store thousands and thousands of different memory-traces? Each memory-trace is a unique pattern on the memory-surface. How large a surface would one need to store so many patterns?

Here is shown a single box. With such a box you can represent two patterns: the box with a cross in it and the box without a cross. If you had two boxes you could have four different patterns. If you had three boxes you could have eight different patterns. Each time you add a box you double the number of patterns that can be shown. With nine boxes (as in a noughts-and-crosses grid) the total number of different patterns would be 512. That means that there are 512 distinguishable ways of distributing crosses over the nine boxes.

If you had a grid made up of ten boxes along one side and ten along the other, then the total number of different patterns that could be shown would be about 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000. In visual terms that would mean that if each pattern were given a separate name, and a thousand such names were written on each piece of paper, and these pieces of paper were piled up, then they would reach to the moon – and back. Not once but several million times. That is the size of the number of patterns which could be represented in this manner with just 100 units. In the brain there are of the order of a trillion units.

Suppose a grid of fine lines transferred to the surface of a photographic plate. Suppose that each of the grid boxes on the surface of the plate was classified as either light or dark (in-between shades would be judged as either one or the other) according to how the photograph had come out. Then by specifying the state of each box one could recognize several billion different objects, provided they were always photographed from the same point of view and distance. That is, provided the image fell on the same part of the plate. If a camel were photographed there would be on the plate a certain pattern of light and dark boxes which would make up the image of the camel. The same would be true for any other image on the photographic plate. Each picture image could be described as a pattern of light or dark boxes. If there are a sufficient number of separate, identifiable boxes on the surface then a vast number of different patterns can be received.

But all this is no more than a long-winded way of saying that a photograph may be taken of a vast number of things, each of which will give a distinct image. Any photograph can be imagined to be made up of tiny boxes or not, without its capacity for receiving images being altered. The box idea is really a way of showing that any surface capable of receiving a recognizable image pattern is capable of receiving a multitude of such patterns.

Dividing the surface of the photograph into boxes does not make it capable of receiving more images, but it is a convenient device for considering what happens at each point on the surface. Any memory-surface that is capable of registering an impression may be considered as being made up of boxes or dots or units. It is enough that each of these units should be capable of change. The minimum requirement for change is that there should be two states which can be distinguished one from the other. These two states might be a cross or no cross, as in the grid pattern, dark or light, as in the photograph boxes, on or off, as with a switch or light bulb.

As soon as there are a sufficient number of such units, each capable of being in one of two states (that is to say capable of change), then there is a surface which can record a huge number of distinct patterns, just as an ordinary photographic plate can.

How the patterns are stored as separate memories will be considered later. It is for convenience in describing this process that the surface is divided into individual units. For the convenience of one’s imagination the units are considered to be spread over a flat surface. Such a flat surface, made up of units each of which is capable of indicating a change, can be called a memory-surface.

Each unit on the memory-surface has a special position, and if the units were lights then a picture would be given if the units in specified positions lit up. In two-dimensional space the position of each unit is given by its relationship to the neighbours which surround it.

It is this fixed relationship in space that allows the memory-surface to record and keep images. If the units kept wandering about after the image had been received then the image would literally go to pieces.

Any one unit is most closely related to the units which are nearest to it in space. Instead of nearness in space one could substitute nearness in sympathy. Nearness in sympathy is another way of saying functional connection.

If you go with your friends to a football match but get split up by the rush of the crowd, you might find yourself standing on your own. The people around you are your neighbours in space, but your friends scattered throughout the crowd are nearest to you in sympathy.

When you use an underground station in London you are surrounded by masses of people who are your neighbours in space. Yet each one of those people is functionally connected to a completely different set of people who are not at that moment spatial neighbours at all. The functional connection of these people is a communication one. They are not actually connected by wires all the time but they are connected by the functional equivalent of communication wires, that is to say, knowledge of telephone numbers, addresses, names, familiarity.

On the flat photographic surface each unit has a spatial neighbour. In the underground station or the football crowd each unit has functional neighbours who differ from the spatial neighbours.

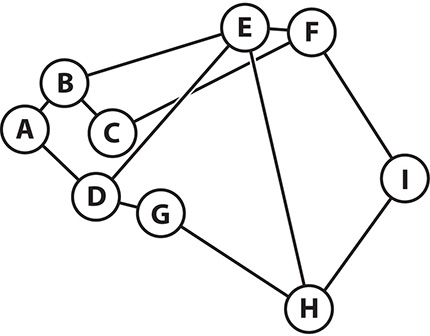

Take nine points as shown in a simple pattern – (a) here – and then for these nine points use nine solid objects like cups. You now connect elastic bands to the handles of the cups as shown. The elastic bands represent lines of communication or a functional relationship. For the moment this functional relationship is exactly the same as the spatial one. Next jumble the cups up as much as you like. The elastic stretches and the positions alter – (b) also here. The spatial relationships are all upset. But the functional relationships are exactly the same.

Suppose you started off the other way round with the jumbled mess, but then sorted it out so that the functional relationships coincided with the spatial ones. You could then forget about the functional relationships and deal only with the much more convenient spatial ones.

Throughout this book all the models and descriptions refer to the memory-surface as a flat one with spatial relationships. Everything that is said in this context can be applied just as well to functional relationships. And by functional relationships is simply meant a communication line. And by communication line is simply meant sympathy, so that when something happens at one unit any other functionally connected unit will feel something of that happening.

Fig. 9b

We can now forget about functional relationships and go back to memory-surfaces with simple spatial relationships, in which each unit is related to its neighbours.

When you take a photograph you expect to get a good picture, to find on the film a true representation of whatever you have photographed. Suppose you came back from a trip abroad and found that there had been something wrong with the film in your camera; the film had been wrinkled in some way and this wrinkling had distorted all your pictures. Or there was something wrong with the emulsion on the film and only part of each photograph had come out. You would be very annoyed. A photographic film is expected to be a good memory-surface. Up to this point it has been assumed that memory-surfaces are good memory-surfaces, and that they faithfully record the image as it is presented to them. It has been supposed that the memory-surfaces are passive and just receive images in a neutral fashion without altering the image.

The wrinkled or blotchy film, however, is a different sort of memory-surface. It is a memory-surface with characteristics of its own which result in an alteration of the received image, so that it is no longer pure and exact.

Fig. 10b

Fig. 10c

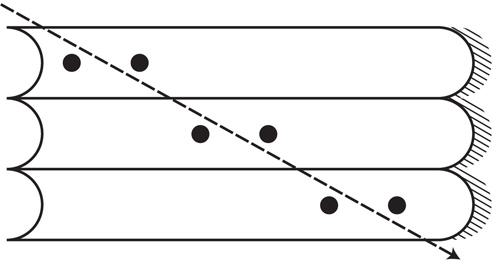

If you walk across a patch of sand and drop marbles at one-second intervals, these marbles will come to form a pattern on the sand. The sand acts as a memory-surface, and the dropped marbles are the memory-trace. From this memory-trace one could tell the direction of your walk and also its speed (from the distance apart of the marbles). The pattern that might result is shown in picture (a) here. Now suppose that instead of the sand there was a special corrugated surface, as shown in cross-section in picture (b). If you were to walk across this corrugated surface at an angle (as shown by the dotted line) and drop the marbles as before, a rather different pattern would result. Neither your walk nor the way you dropped the marbles is any different from what it had been before. The difference in pattern is due to the memory-surface which has done something to the marbles instead of just accepting them where they fell. It has altered the pattern presented to it and comes to show something rather different. This is rather like the wretched film that spoiled the holiday photographs. If you did not know anything about the nature of the corrugated surface and just looked at the position of the marbles, you might suppose that the path of the walk had been zig-zag instead of straight – picture (c).

Suppose the surface was neither sand nor corrugated, but concrete. The dropped marbles would then jump about and roll all over the place in a random manner from which one would not be able to tell anything about the walk.

Here are shown the patterns that would result in all three cases. The first pattern is made by a true memory-surface. The second pattern is made by a memory-surface which does something to the material received. The third pattern is also made by a memory-surface which does something to the material received, but in a completely random manner.

A good memory-surface gives back exactly what has been put onto that surface. A bad memory-surface gives back something different. The difference between what is put onto the surface and what is given back (or stays there) is what the memory-surface does to the material. The material is changed and processed by the memory-surface. This processing is not necessarily an active or a worthwhile business, but just the way a bad memory-surface works even when it is trying to do its best.

The extraordinary thing is that a bad memory-surface can be more useful than a good memory-surface when it comes to handling information. A good memory-surface does nothing but store information, and a separate system is required to sort it out and process it. A bad memory-surface actually processes the material itself and so is a complete computer.

The two ways in which a bad memory-surface can be bad are distortion and incompleteness. Distortion means that things are shoved around, emphasis is changed, relationships may be altered. Incompleteness means that some things are just left out. Paradoxically, this is a tremendously important deficiency, for when some things are left out there must be some things which are left in. This implies a selecting process. And a selecting process is the most powerful of all information-handling tools.

It is quite likely that the great efficiency of the brain is not due to its being a brilliant computer. The efficiency of the brain is probably due to its being a bad memory-surface. One could almost say that the function of mind is mistake.