THERE ARE TWO convenient models of the insight situation. The first model involves what might be called short-circuiting. A long and tedious way of carrying out some task suddenly gives way to a quick and neat way of doing it. Once this has come about it is so obvious that everyone exclaims, ‘Of course, why didn’t we think of that before?’ It is rather like driving to a favourite restaurant by a long, roundabout route. Suddenly you realize that if you go through a side street the restaurant is within walking distance of your home anyway. The second model is the eureka situation. A problem has been impossible to solve. Then suddenly in a flash of insight and without any further information the solution becomes clear. Both these examples could occur quite easily on the special memory-surface.

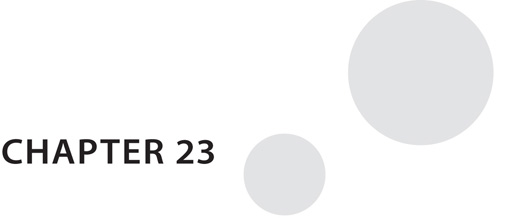

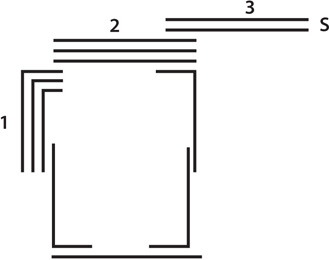

The short-circuiting situation is shown in a d-line diagram here. The sequence of attention areas is shown starting at position (A) and following all round the circuit to reach the completed task at position (B). There are nine steps from start to completion. This sequence is inevitable, since the flow of attention must always be towards the better established d-line fragment. Thus from (A), flow must go towards (C), and once at (C) it must proceed around the whole circuit. (It cannot just flow back again because of the tiring factor, without which there would never be any flow at all.)

In the second d-line diagram here the layout is exactly the same, but this time the sequence is only three steps long instead of nine. A short circuit has occurred. Exactly the same d-line fragments are present, with exactly the same degree of emphasis. How has this short circuit, or flash of insight, come about? The explanation is surprisingly simple. If the first attention area is (C), then flow has to be towards (A), since this is better established; and once at (A), flow continues directly to (B). It is all a matter of the first attention area.

In the above example a flash of insight has come about simply as a result of looking at one part of the problem before another. A very slight shift in attention can make this huge difference. The emphasis is on slight. How then does this slight shift in attention come about?

The d-line diagram shown here would never stand in isolation, it would follow on from flow along some other d-line pattern, and this flow would then lead in to the pattern shown. Depending on what the previous patterns were, the flow might lead into the pattern shown at either (A) or (C). The usual entry point would be (A), but if one day because one had been thinking of something quite different the entry point were (C), then the flash of insight would occur. It would be inconceivable that the whole sequence of thought before the problem was arrived at should be absolutely identical on every occasion. On the other hand, insight is not frequent because a dominant entry point may remain the same even though the preceding patterns are different.

Fig. 73

The change in entry point to the d-line diagram of the problem could also come about through a change in internal patterns. Some mood or motivation change could emphasize some part of a preceding pattern more than usual, and this would lead to an unusual entry point. An external object present at the time, or before, could also affect the entry point. Archimedes splashing around in his bath had the entry point altered by the idea of water. Newton walking in the garden had the entry point changed by the apple that dropped on his head. These are trivial things in themselves, but if they serve to change the entry point into the problem sequence then they can set off a flash of insight.

The three important points about the insight phenomenon are as follows:

1. The problem sequence itself (i.e. the information available) remains completely unchanged.

2. A different entry point into this sequence can change the outcome markedly.

3. The change in entry point can come about for trivial unconnected reasons that affect not the problem itself but what has gone before.

Once the solution has been reached on one occasion why should it remain permanent? Here one might consider the peculiar pleasure that accompanies a ‘snap’ or insight type solution. Once the answer is known, then attention shifts from the starting-point of the problem to the end point. Starting at the end point one works backwards, and then there is no difficulty about sequences. One could also say that every slight initial difference which brought about the different entry point could be slightly reinforced by the pleasure of solution, and so become the usual entry point. With time, the pathway would become established as the dominant one. It is important to remember that insight solutions can be forgotten, just as jokes can. One is left with a vague feeling that it can be done, but does not quite remember how.

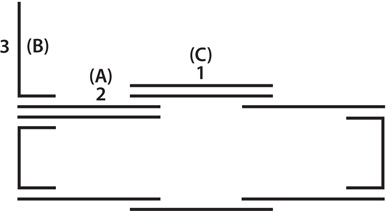

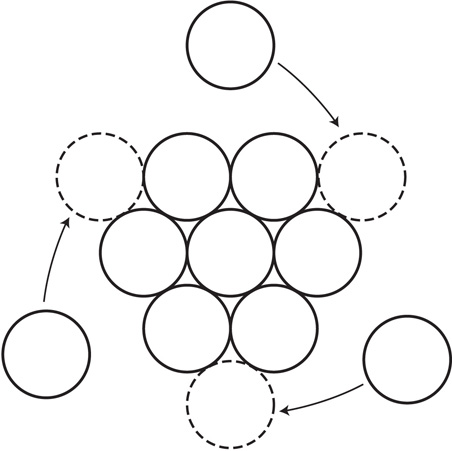

Another insight situation is shown as a d-line diagram on this page. In the top diagram the thought flow chases round and round in a circle. By the time the flow returns to the starting-point the tiring factor has worn off so it can take that path again. Without any change in the d-line pattern, but with a change in the entry point to the sequence, the flow escapes from the circular trap and quickly reaches (S), which is the solution point. This is not an example of short-circuiting but of a problem which did not have a solution. A slight change in the entry point into the sequence suddenly produces a solution.

Fig. 74

Fig. 75

If you give a person a postcard and a pair of scissors and ask him to cut a hole in the postcard big enough to put his head through, a curious thing often happens. You explain to him that a hole is space surrounded by continuous postcard without any joins. (Those who wish to try it for themselves could pause here.)

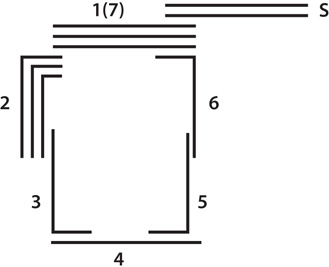

Most people start to cut into the postcard and then around it to make a spiral as shown here. They either finish the spiral or give up as soon as they realize that they will end up with something that has two ends. They then discard the spiral and start again on a fresh postcard.

The fascinating point is that they were so near to solution with the spiral but could not get there. All one needs to do is to regard it not as a spiral but as a long strip. If one were asked to make a hole in a long strip one would at once cut it down the middle. This is shown for the postcard spiral here. The hole that results is easily big enough to put one’s head through.

This postcard situation is shown in d-line form here. One starts off with the postcard and then has some vague notion of a thin rim of postcard. This leads on to the spiral effort. Once the spiral is achieved this leads very strongly to the two-end realization and the path is blocked. When it is pointed out that a spiral is also a strip then solution follows. In remembering the solution one then works back from the slit in the strip to the spiral as a strip-producing method.

If one were to put down the spiral cut postcard and then pick it up again later one might be more able to see it as a strip than as a spiral. The interesting thing is that onlookers who have not been concerned in cutting out the spiral are more apt to see it as a strip and to reach the solution.

It might be suggested that there was a switch point at the d-line fragment marked ‘spiral’, and that there was a choice of two paths, one leading to the ‘two-end’ difficulty and the other leading to the ‘strip’. Some emphasis at this point might have been sufficient to cause the ‘strip’ path to be chosen and the problem solved.

Undoubtedly this type of problem-solving does also occur on the special memory-surface. Whenever there is a choice point and the difference in emphasis between the two alternative routes is slight, then a slight change in emphasis may suddenly make solution possible. This very slight change in emphasis may come about for a variety of reasons, including emotional changes or use of that d-line segment by another pattern recently enough for the short-term memory facilitation to be still active. Once the switch over has come about on just one occasion then the sequence of attention in the problem is changed, and this is what preserves the solution. There does not have to be a permanent change of emphasis at the switch point.

The insight phenomenon is not only possible on the special memory surface but is inevitable, since the actual sequence in which patterns are activated determines the outcome as much as the nature of the patterns themselves. Thus the special memory-surface is capable of both the gradual type of learning and also the sudden insight type.

The insight type of learning is extremely valuable because a certain pattern sequence, which has been built up that way because of chance encounters with information, can suddenly be restructured to make maximum use of that information. The other important point is that if insight is due to a change in the entry point into a sequence, then one can deliberately increase the possibility of insight solutions. This would be done by attention not to the problem itself but to the surroundings or antecedents of the problem, so that the entry point might be changed. It could also be done by deliberately starting attention at different points, or even by using random disrupting stimuli from outside. All this is dealt with later under lateral thinking.

In humour there is a sudden switch over from one way of looking at things to another. This is exactly similar to the insight process. Both processes indicate the type of system that must be operating. Neither insight nor humour could occur in a system that proceeded in a linear fashion as does a computer. In a linear system the best possible state would always be the current one, and there would be no question of suddenly snapping over to an insight solution.

It is interesting to suppose that the pleasure of humour is related to the sudden pleasure of insight solutions. Indeed, when people are suddenly shown an insight solution to a problem they often burst out laughing. This pleasure may well be an essential part of the insight mechanism because the pleasure of solution enables the solution point to become the starting-point in the problem sequence, and in this way the solution is retained.

On the whole the insight mechanism is an extremely valuable one for information-processing, because it enables the maximum value to be obtained from information which has had to organize itself according to the time of arrival on the memory-surface. The insight mechanism compensates to some extent for this deficiency. Effective though insight may be, it is a haphazard and unreliable process.

The reality of the insight switch over from one way of looking at a situation to another is shown by an arrangement of ten coins in the form of a triangle, as here. The triangle points to the top of the page and the problem is to get the triangle to point to the bottom of the page by moving only three coins.

There are several ways of doing this, but many people find it rather difficult, perhaps because they get confused by the number of different approaches that can be tried. Here is shown what is probably the most elegant solution. Instead of being regarded as a triangle, the pattern is regarded as a rosette with three extra points. If each point is moved round to the next position the triangle is reversed. The interesting thing here is that once the solution has been seen and seen to be effective it becomes permanent at once.

In all these problem-solving situations one probably ought not to ignore the fact that there is a definite starting situation and a desired end situation, and that a solution does link the two up so creating one coherent pattern out of two separate ones. In itself this physical change on the memory-surface might account for the way in which in a problem situation a single occurrence leads to a permanent record, whereas on other occasions the basic pattern may only be changed by repetition. It may be a matter of the absence of competing pathways. Problem solutions which require the addition of some last bit of information that completes the circuit often give the impression of an insight solution.

When a particular pattern of thought-flow leads to some action, then the result of that action can lead to further activity on the special memory-surface. If you feel hungry you might pick an apple, and then the sight of the apple will suggest the use of a knife to peel it, and so on. It could of course all be planned beforehand, but obviously there are situations where an action results in a new pattern being presented to the memory-surface. There is nothing particularly special about this, and as far as the memory-surface is concerned there is just a change in the environment. It cannot matter whether this change occurred on its own or as a result of some action. If as a result the basic pattern is changed, then this will be changed by one of the processes described before.

Fig. 81

It might, however, be worth considering here a rather special type of behaviour which can facilitate change on the memory-surface. This behaviour is only a special example of any other action that changes the environment. The action here is that of writing, or notation, in the course of thinking.

The importance of the sequence in the natural flow of thought has been stressed repeatedly. Notation takes some pattern out of the sequence and freezes it in time by transferring it to paper. That pattern can then come back into the sequence at another time. Thus new sequences can be set up and the benefits of a change in sequence can be considerable. It is not, however, much use leaving the feature in notation form on a piece of paper, for then it will only be attended to when its natural turn comes round in the flow of attention. And that way the sequence will be maintained. There has to be some deliberate or artificial time for re-entry, paying attention to the feature. This could be as simple as arranging the notation in a spatial sequence that had nothing to do with the natural flow sequence and then just going over the notation according to the spatial sequence. In ordinary discussion a new idea may often be set off by another person putting back into your mind an idea out of its natural sequence. In argument this is exactly what one tries to do in order to change the other person’s viewpoint.

All the methods described so far are ways in which the natural development of a pattern can be improved. Each special memory-surface has its own unique experience and from this develops its own established patterns. This unique experience can be so structured by education that the established patterns end up as being rather similar.

One can improve on the unique experience of a single memory-surface by pooling the experience of several, through communication. This ought to give more effective organization of the information available, because idiosyncrasies of experience would be ironed out. In practice this system does not work as well as it might. Very often the idea that results is not formed from common experience but from the unique experience of one individual, and is then accepted by the others. Also, pooling of information can just as firmly establish an erroneous pattern, if this arises from common experience; for instance, the idea that the sun goes round the world.

On the whole, communication probably does improve the established patterns by freeing the information available for self-organization from the chance nature of individual experience. For the same reason it might make difficult those new ideas that arise precisely from the chance nature of individual experience.

One striking thing emerges from consideration of how the established patterns on the special memory-surface can come to be changed, and this follows directly from the way the surface is organized. On some occasions the slightest change at a sensitive point can lead to a huge over-all change. On other occasions no amount of effort at an insensitive point will lead to the slightest over-all change.