BOTANICAL NAME

Pinus longaeva (Great Basin bristlecone pine); Pinus aristata (Rocky Mountain bristlecone pine)

DISTRIBUTION

California, Nevada and Utah, USA.

OLDEST KNOWN LIVING

SPECIMEN

The Methuselah Tree in California: over 4,600 years old.

HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE

Known as the ‘tree that rewrote history’ because it provided wood with a tree-ring chronology spanning 8,000 years, allowing the carbon-14 dating technique to be accurately calibrated.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Classified on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2011 as of ‘least concern’.

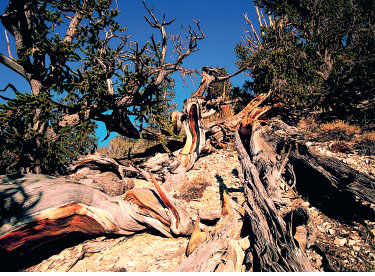

Bristlecone pines growing on south-facing slopes of the White Mountains in California.

On a barren mountainside in eastern California’s White Mountains, a grove of ancient pine trees clings to life. Bleached by the sun, smoothed by the corrosive force of fierce winds bearing sand and ice, these Great Basin bristlecone pines (Pinus longaeva) have been moulded into grotesque natural sculptures by their inhospitable environment. Undistinguished by size or beauty, these strange trees are, however, incredibly old, and are thought to be able to reach ages of over 5,000 years. Here stand the Schulman Grove and the famous Methuselah Tree, which has a verifiable age of over 4,600 years according to carbon-dating research. It was named by Dr Edward Schulman in 1957, after the Hebrew patriarch of the Old Testament whose long lifespan has made him a byword for longevity.

Looking out across an environment that has remained almost unchanged for more than 10,000 years, it seems possible to step outside time and share a moment of silence with these living organisms, which began their lives before the great pyramids of Egypt were constructed. Even before the rise of the great empires of the Greeks, Mayans and Romans, the Methuselah Tree was already one of Earth’s elder statesmen.

Two species of bristlecone pine exist. Though growing only 260km (160 miles) apart, those found on the high ridges of the Great Basin country (extending from the eastern border of California across Nevada to Utah) reach the greatest age. The Rocky Mountain bristlecone pines (Pinus aristata), which reach ages of up to 1,500 years, are to be found in an area that extends from the eastern slopes of the southern Rocky Mountains in Wyoming through Colorado and down into New Mexico. The environment in which the bristlecone pines live seems an unlikely place in which to find trees of such antiquity. In fact, it is the very harshness of this environment, and the bristlecone’s response to it, that have enabled the tree to achieve such a great age.

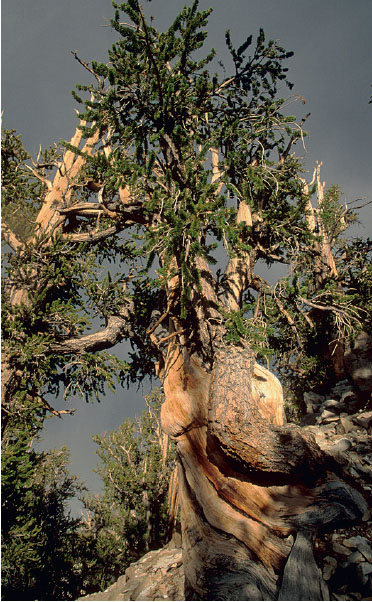

The oldest bristlecone pines are found on the north-facing slopes of California’s White Mountains, where extremely harsh conditions prevail.

The Great Basin bristlecone pines grow on steep, rocky slopes at an altitude of 2,750–3,500m (9,000–11,500ft) above sea level. Between November and April each year, temperatures plummet to well below freezing and the area may receive 2.7m (9ft) of snow. These conditions are exacerbated by the ferocious winds that scour the mountainsides. The bristlecone pine has adapted by lengthening its growing season and by putting on new growth when temperatures are much too cold for other plants.

The arid conditions in which bristlecone pines live means that timber from fallen trees can lie on the ground without decomposing for thousands of years.

Most of the trees are under 9m (30ft) tall, and much of their wood – on the windward side, at least – is dead. The sparse crowns of twisted and contorted branches are supported only by narrow strips of living wood. The ability of the bristlecone to live in nutrient-poor soils and to conserve water has been vital to the survival of the species. The tree has developed special waxy leaves (needles), which may not be shed for over 20 years, thus helping to reduce evaporation and conserve moisture; it also contains high levels of resin, which acts as a wood preservative and which is exuded to form a waterproof layer over any exposed branches. To maximize water absorption, the tree also has an extensive network of shallow roots.

Evidence that the great longevity of the trees is directly related to the harshness of their environment is provided by the fact that the average age of bristlecone pines on south-facing slopes in the White Mountains is typically around 1,000 years, whereas on north-facing slopes, the average age rises to over 2,000 years. Entire groves of trees that are over 4,000 years old stand on the north-facing slopes, and it is amid one of these groves that the ancient Methuselah Tree is found. The appearance of bristlecone forest on north- and south-facing slopes is markedly different. While the southern slopes have many healthy-looking trees, covering the hillside in quite dense forests, north-facing slopes contain trees that are much more widely spaced, squat and gnarled, with many dead branches. The severity of the environment on the north-facing slopes causes the growth rings to be more tightly packed, which in turn makes the timber more durable and the trees longer-lived. The durability of the timber is so exceptional that scientists have found dead wood, which, amazingly, has been shown to be over 8,000 years old, lying intact close to living trees.

A forest consisting of trees that are thousands of years old can afford to regenerate at a leisurely pace. Only a handful of new seedlings need to germinate successfully each century to ensure the forest’s survival. Bristlecone pines are found in pure stands but often form communities with limber pines (Pinus flexilis) and other tree species, as well as understorey plants such as sage brushes (Artemisia spp.), wax currant (Ribes cereum) and curl-leaf mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus ledifolius). Birds such as the mountain bluebird, the chickadee and Clark’s nutcracker feed on their seeds. The latter is most important for the bristlecone pine’s regeneration, because it collects seeds and buries them in caches in the soil, thus helping the seedlings to gain a foothold in the inhospitable terrain.

The Prometheus Tree

In 1964 Donald R. Currey, an undergraduate researcher, asked the US Forest Service if he could cut down one tree – to study the annual growth rings of bristlecone pines growing in a grove beneath Wheeler Peak. The Forest Service agreed, but unfortunately the tree he cut down revealed later that it had no fewer than 4,862 rings and a hollow core, which meant that it had probably been growing for over 5,000 years and was several hundred years older than the oldest still growing today. It became known as the Prometheus Tree, a name from Ancient Greek myth: Prometheus brought fire (symbolic of knowledge) to humans.

Despite the tragedy of the felling of the world’s oldest verifiable living organism, the knowledge gained from studying it has added to the scientific understanding of carbon dating and climate change over the past 11,000 years.

The wind-sculpted trunk of a living Bristlecone pine in the Methuselah Grove high in the White Mountains. Over time, the harsh climatic conditions turn many ancient trees into striking organic sculptures.

Because bristlecone pine wood is extremely durable and can survive intact for thousands of years, scientists have been able to look not only at the ring sequences of living trees, but at those of dead trees that have remained preserved on the ground. This fact enabled a highly significant breakthrough to be made in the science of radiocarbon-dating archaeological artefacts. During the late 1950s, the study of tree rings, using wood that was dated to the exact year of its formation, enabled scientists to confirm the discrepancy between the radiocarbon ages and actual calendar ages of objects containing carbon, and recalibrate their method of measurement. It was found that many objects were 1,000 years older than previously thought.

In the 1960s, the overlapping of living ring sequences with those of dead trees enabled the first calibration curve based on a continuous tree-ring sequence stretching back more than 8,000 years to be constructed. This research also revealed valuable information about the climatic conditions of the past. Tree rings are still used today to calibrate radiocarbon measurements and tree-ring libraries representing different calendar ages are now available, providing records that go back over 11,000 years. While trees such as the waterlogged oak (Quercus spp.) are also used, the enormous significance of data obtained from the bristlecone pine has justified its name as the ‘tree that rewrote history’.

Bristlecones are able to reduce their energy requirements for living to a very low level by shedding their branches and allowing parts of the tree to die back. They rarely exceed 9m (30ft) in height but their timber is remarkably dense and durable.