BOTANICAL NAME

Taxodium mucronatum

DISTRIBUTION

Often near rivers, springs, marshes or former swampland: widespread and locally common in Mexico; rare and localized in Guatemala; a few examples in Texas, USA, where it is in danger of extinction.

OLDEST KNOWN LIVING SPECIMEN

The tree known as El Tule, growing at Santa Maria del Tule, near Oaxaca, Mexico: 36.3m (119ft) in girth, or 53.7m (176ft) including irregularities at 1m (3¼ft) from the ground; estimated age: 1,200–3,000 years old.

RELIGIOUS SIGNIFICANCE

Sacred to the ancient peoples of Mexico.

MYTHICAL ASSOCIATIONS

Linked to Zapotec origin myths.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Classified on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2011 as of ‘least concern’.

El Tule is considered to be one of the world’s stoutest trees, measuring 36.3m (119ft) in girth.

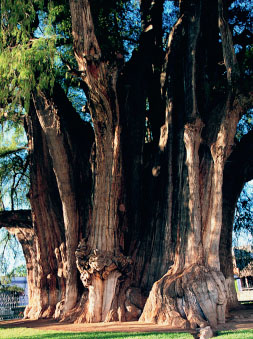

The Montezuma bald cypress known as El Tule is an astonishing tree. To stand before it and look up into its crown is like looking at a living version of Notre Dame Cathedral. Its fluted bole is reminiscent of the flying buttresses that support this architectural masterpiece. Both are immense; both demand the same degree of reverence and awe. El Tule is to be found near the village that has taken its name from the tree: Santa Maria del Tule, some 14km (9 miles) from the town of Oaxaca, in southern Mexico. Also known as the ahuehuete, the Montezuma bald cypress (Taxodium mucronatum) is a species that grows almost exclusively in Mexico.

Some botanists consider this to be the same species as the tree known as the swamp, southern or bald cypress (classified as Taxodium distichum), which is found in the south-eastern United States and grows in a similar habitat. Recognition of its colossal size, beauty and longevity led to its official recognition as the National Tree of Mexico in 1921 and various ancient individual specimens are protected as ‘monuments’.

Montezuma bald cypresses generally grow to a height of 20–30m (65–100ft), but can exceed 35m (115ft). El Tule is the largest individual in Mexico, but it is not actually the tallest; other giant trees also exist. A tree standing in Mexico City’s Chapultepec Park was recorded, using a laser, as being 37.8m (124ft) high, making it the tallest.

The magnificent crown of El Tule is supported by many boughs that are reminiscent of flying buttresses.

The tree is an evergreen, but in the winter and spring months the foliage can appear a rusty-red colour as the new leaf buds develop. An interesting feature of these slow-growing giants is the apparent tendency of their massive, fluted and burr-covered boles to split as they grow, giving the impression, in old age, that they are not one but several trees joined together. This can be a complicating factor when trying to estimate the age of ancient trees. The distinguished Mexican botanist Maximíno Martinez, founder of Mexico’s Botanical Society, who made a detailed study of the country’s Montezuma bald cypresses, concluded in the 1950s that trees such as El Tule were not the result of a fusion of separate individuals, but of the division of the main trunk at its base. DNA studies undertaken in 1996 also confirmed that it is in fact a single tree.

The Montezuma bald cypress produces new foliage that is a rusty-red in colour.

In his Historia Natural y Moral de las Indias of 1586, the Spanish chronicler José Acosta noted that according to the local Zapotec Indians, El Tule was a truly colossal tree some 100 years earlier, able to provide shade for 1,000 people. Though the exact date is not known, at some point during the fifteenth century it was struck by lightning, which ripped the tree asunder leaving a huge hollow, while reducing the magnificent crown to a mass of splintered branches and tattered foliage.

When the first Europeans arrived in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, where El Tule stands, it was still an impressive sight. Acosta, who provided the first written record of it, described it as a huge shell of a tree, which measured 16 arm’s lengths (a little under 27m/89ft) near its base, which was split into three sections. In a letter written on 7 March 1630, the Spanish priest Bernabé Cobo described the tree as follows:

‘Amongst the ruins of the old village, there is a hollow tree so wide at its base, that it looks as if it would make a very capacious dwelling; it has three entrances that are so huge that you can ride through them on horseback, and there is room inside for 12 horsemen; four of us who came rode in on our horses and there was still room for another eight, I measured it outside having brought with me a ball of thread for the purpose, and it measured round its base 26 varas [17.5m/57ft]; … it is alive, still with many branches and leaves, although years ago a lightning strike damaged most of its branches. From here to the town of Oaxaca it is three leagues …’

Almost 400 years later, the tree has risen again. The gaping hollow – estimated to have been some 12–18 sq. m (129–93 sq. ft) in size – has been filled with new timber, and the regenerating branches have become mighty boughs that support a dome of foliage some 44m (144ft) across, rising to a height of almost 35m (114ft). It is now one of the world’s greatest trees, with a bole measuring 36.3m (119ft) round at breast height or 53.7m (176ft), including all the irregularities of the gnarled and buttressed trunk.

During the seventeenth century the hollow inside El Tule was reputed to have been large enough to be able to hold twelve men on horseback.

All was darkness when the Zapotecs were born. They burst forth from the old trees, like the ceiba (and El Tule) from the stomachs of the wild beasts they were born, like the jaguar and the lizard.

ZAPOTEC ORIGIN MYTH

The exact age of El Tule is unknown, with estimates ranging from between 1,200 and 3,000 years old. The best scientific estimate, based on growth rates, is 1,433–1,600 years old. Interestingly, there is a local Zapotec legend that states that it was planted about 1,400 years ago by Pechocha, a priest of Ehecatl, the Aztec wind god, which is very much in line with the scientific estimate. Further north, near San Luis Potosi, is a group of ahuehutes, the largest of which is just 22m (72ft) tall and 2m (6½ft) in diameter. Core sample analysis has shown that one of the trees in this group has a confirmed age of 1,140 years. El Tule has a diameter approximately five times greater than this 1,000-year-old tree, which is why some people are tempted to suggest that it is one of the oldest trees on Earth.

The native Zapotec Indians who were living in the vicinity of El Tule when the Spanish conquistadores arrived in the early sixteenth century called the site Luguiaga (later renamed Santa María by the Spanish), which has been roughly translated as ‘amongst the reeds’. This name provides evidence to support the descriptions made by early Spanish observers of the local environment: that it was a large, reed-filled swamp, or certainly flooded for much of the time.

Before the arrival of the Spanish in Mexico the lingua franca in Mesoamerica was Nahuatl – the language of the ruling Aztecs, whose last emperor was the distinguished warrior Montezuma II (1466–1520), from whom the Montezuma bald cypress takes its name. Luguiaga was also known, more widely, by its Nahuatl name of Tollin or Tullin. This is a generic term for aquatic plants, and it evolved into the hispanicized word tule. The term still used today for all Montezuma bald cypresses, ahuehuete, is also a Nahuatl word meaning, in Spanish, viejos de agua – literally, ‘ancients of the water’. Indeed, the trees naturally occur next to rivers, streams, springs or swampy ground and the roots have adapted by producing pneumatophores or ‘breathing roots’.

It is interesting then, to note that El Tule and other large Montezuma bald cypresses are now found in locations that are distinctly arid, bearing testament to the fact that much of Mexico has become desertified over the last 2,000 years. That El Tule began its life in a swamp or on the edge of a lake or river seems certain, but it has had to depend upon water drawn from very deep down, by its network of roots, in order to survive. Since 1952, to help compensate for the increasing scarcity of underground water, the survival of the tree has been assisted by the installation of an underground irrigation system designed to water its roots.

As is recorded at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, the ancient Aztec people, the Mexica, took advantage of the Montezuma bald cypress’s demand for large amounts of water and the ability of its roots to bind rocks and soil together, and put it to very practical use. By planting trees in the form of palisades within shallow lakes and filling the spaces in between with earth, wetlands could gradually be drained and turned into land suitable for growing crops. This was done around the once extensive Lake Texcoco, on which the Aztec city of Tenochtitlán was built – now the site of the vast Mexico City.

El Tule was a great tree during the period in which one of the most advanced empires in the world, that of the Aztecs, was at its peak; in some ways it is symbolic of the history of Mexico’s native peoples who have, despite adversity, managed to survive. Today El Tule stands proud: not just as part of Mexico’s history, but as an integral part of its future.

This burr on El Tule is known by local people as ‘El Leon’ because of its resemblance to a lion’s mane.