BOTANICAL NAME

Quercus robur (the common, English or pedunculate oak) Quercus petraea (sessile or durmast oak)

DISTRIBUTION

Across Europe, from Ireland in the west to Asia Minor in the east, and south to the Mediterranean coast of western North Africa. Quercus robur and Q. petraea are just two of over 600 species of oak that occur right across the northern hemisphere from Asia to North America, with the area of highest species diversity being Mexico.

OLDEST KNOWN LIVING SPECIMEN

Quercus robur: The oldest living specimen is believed to be the Kongeegen or King’s Oak growing in the forest at Jaegerspris Nordskov in Denmark. It is currently 10.38m (34ft) in girth, but was measured at over 14m (46ft) in 1976, before part of the trunk broke off. The largest-trunked oak is the great Rumskalla or Kvill Eken in Sweden, which is currently 14.75m (46ft) in girth.

Quercus petraea: The largest and possibly oldest sessile oak is thought to be either the Pontfadog Oak in Wales, which has a girth of 13.38m (44ft), or the Marton Oak in Cheshire, England, which is 13.4m (44ft) in girth.

RELIGIOUS SIGNIFICANCE

Sacred to the ancient Norse, Germanic and Celtic peoples, and to the Greeks and Romans; some individual trees have become shrines.

MYTHICAL ASSOCIATIONS

Associated with the gods of thunder and lightning among ancient European peoples, and with fertility; individual trees have also become associated with figures of legend such as Robin Hood.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Q. robur classified as ‘of least concern’; Q. petraea classified as ‘vulnerable’ on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2001.

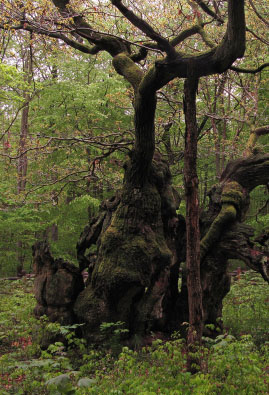

One of several hundred great oaks that can be found in Windsor Great Park, UK.

Of all the native trees of Europe, the mighty oak has held a special fascination since the earliest times. With its distinctive broad crown, supported by a massive trunk in old age, this handsome tree has become an enduring symbol of strength, protection, durability, courage and truth.

When the Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus (1707–78) used the term robur (from the Latin word for strength) to describe the common oak (Quercus robur), he was referring to two features that set it apart from many other trees: the robustness of the living tree and the great strength of its timber.

Oak timber is indeed synonymous with strength and durability. For thousands of years it has been used for construction purposes wherever permanence is required. Tree-ring evidence has proved that oak wood was being used in Germany some 9,000 years ago, and in Ireland 7,200 years ago. In Scandinavia, archaeologists have found that early Bronze Age coffins were hollowed out of oak trunks (or made use of naturally hollow ones), in order to give safe passage to the dead during their long journey to the next world. In Britain, King Arthur’s Round Table was reputedly made from an enormous piece of oak, and the oak coffin (made from a hollowed-out tree) that rests in Somerset’s Glastonbury Abbey is said to contain his remains.

Both the common and the sessile oak are very hardy and have co-evolved to be able to withstand attacks by pests and diseases, as well as exposure to extremes of temperature and drought. Even during the longest and most severe droughts, oaks seem to show few signs of suffering. This is true both of those that commonly grow in clay soils, which hold water well, and those found in drier, sandy regions. The vast edifice of trunk and crown is anchored to the ground by a network of tenacious roots. For the first few years of its life, the oak sends a large tap root into the soil, but other lateral roots soon develop into buttress roots, which stabilize the tree as well as drawing up water (around 90 litres/20 gallons a day).

While it is impossible to state with certainty which tree is the oldest oak in Europe, we can say that there are a number of great trees dotted across the continent, some of which have probably lived for more than 1,000 years.

There is much debate about just how old the most ancient oaks of Europe really are. The noted British dendrologist and co-founder of the Tree Register of the British Isles, Alan Mitchell (1922–95), felt that claims about the great ages of some oaks were often misguided. By plotting girth against age, he showed that in their early years oaks actually grow quite fast, on average about 2.5cm (1in) per year, and that maturity is reached by about the age of 250 years, after which time the tree will slowly begin to die. ‘The only open question’, he wrote, ‘is how much and for how long an oak over 25ft [7.6m] round can decrease in vigour, and so how much older than, say, 250 years it can be … to be 1,000 years old, it should be around 40ft [12m] round.’

One of the magnificent ‘Dodders’ in Windsor Great Park.

Oak trees have always been synonymous with strength and durability.

The dating technique refined by dendrologist John White disagrees with the assumption that the trunk of an oak (and other ancient trees) will grow fairly constantly at about 2.5cm (1in.) per annum, and showed many ancient trees to be twice as old as previously thought. White’s method is based on measurements of a tree’s girth, and comparison of this data with other trees of the same species, size and, wherever possible, known planting dates on comparable sites. It also recognizes that trees grow at different rates during the different phases of their lives: formative, middle and old age.

King Offa’s Oak at Windsor in the third and final stage of its life – a collapsing giant over 1,000 years old.

The life of an oak is perfectly summed up by this anonymous quote: ‘An oak tree grows for 300 years, rests for 300 years and then spends 300 years gracefully expiring.’ Traditionally it has been considered that the biggest oaks in terms of girth are the oldest oaks. While this may be true, research has shown that trees growing in challenging environments, such as those that are waterlogged, those growing at high altitudes or subject to severe cold, have much smaller trunk sizes relative to their age. It is possible that in the future the oldest oak in Europe may have only a modest girth compared to those colossal oaks that are considered ancient today. Many of the largest-trunked trees in the UK have been pollarded in the past, or have undergone a natural process similar to that of pollarding.

A mature oak in bluebell woodland.

From medieval times until about 1800, pollarding was standard practice in many woodlands: it involved cutting off the trunk about 2.4m (8ft) up when the tree had reached a suitable height and at intervals thereafter, so that successive crops of smallwood (wood of a smaller diameter than the trunk, and useful for a variety of purposes) could be harvested later. The tree would re-sprout rapidly, and within a few years put on a much greater volume of foliage – often on about six spreading branches – than would a ‘maiden’, or uncut, tree. While a maiden tree depends on its original trunk, and dies when this does, a pollarded tree can continue to put out new shoots into old age, long after the original trunk has become hollow. In the UK, the discontinuation of pollarding may well be catastrophic for some of the most ancient oaks.

Oak leaves and bark provide food or habitat for more insect species than any other European tree: at least 280 insect species are associated with oaks.

Ageing oaks is a very complicated business and there are a number of differing views on the subject. Guidelines recently produced for the Ancient Tree Hunt, for example, drawn from current research, stipulate that a 400-year-old oak could measure between 3–8m (10–26¼ft) in girth at a height of 1.3m (4½ft) depending on a variety of factors such as tree form (whether a pollarded or coppiced tree, for example), historic management and location. There are a number of other influences that affect the growth of an oak, such as soil type, altitude and exposure, but their influence is much more difficult to quantify. Interestingly, managed pollards are frequently found to be much older than their girth size might otherwise suggest, wherever they are, while pollards growing in woodland and on poor soil can be twice the age of a maiden tree that has grown in the open.

Another potential complication is whether a tree is a single trunk or was once a twin stem, as in the case of the Queen Elizabeth I Oak at Cowdray Park in southern England. It, like many of the UK’s oaks with a girth of over 10m (33ft), formerly had two distinct main stems. However, the tree is still likely to be 600–700 years old. A good indication that a tree may have had two stems is given by its overall ‘footprint’, which will be more oval than round. This is also the case for the Major Oak in Sherwood Forest, Nottinghamshire, which is now considered to be nearer to 600 years old rather than 1,000 years old, as had previously been thought.

The ages given in the section below are estimations that have been made by taking into account the current scientific understanding of the ages of Europe’s great oaks. Much research is now suggesting that the ages of the UK’s and Europe’s oaks should be reduced from previous estimates. Some researchers in the Netherlands and Germany believe that very few oaks live to over 500–600 years old, with perhaps a few examples living beyond 850 years. It is generally agreed, though, that some trees, such as the King’s Oak in Jaegerspris Nordskov in Denmark and the Pontfadog Oak in Pontfadog, Wales have the potential to be over 1,000 years old. Whether their real ages are 500, 600, 850 or even 1,000 years old, the oaks described in this chapter are immensely old organisms that we should celebrate and protect as best we can for forthcoming generations as reservoirs of biological continuity, gene banks and as part of our living and cultural heritage.

The UK is richer in ancient oak trees than almost any other European country. Indeed, the Royal Parks at Windsor and Richmond near London contain more oak veterans than some entire European countries. However, this is not to say that there are not some truly magnificent ancient oaks to be found across Europe, or that the oldest oak is British.

The fact that so many ancient oaks are to be found in the UK is attributed partly to the land-tenure system that has prevailed since 1066, the absence of any large land-based wars (unlike the Napoleonic wars, for example, which led to the felling of hundreds of thousands of trees in Continental Europe) and the discovery of vast deposits of coal, which reduced the demand for timber. According to the Ancient Tree Hunt – a project that has recorded over 100,000 ancient and notable trees throughout the UK – in 2012 the UK had at least 43 oaks that exceeded 10m (33ft) in girth, and nine which were larger than 12m (40ft). These comprised an almost equal number of common and sessile oaks.

The Queen Elizabeth I Oak at Cowdray Park in Sussex, UK, showing all the signs of being ancient with a hollow, broad trunk and reduced canopy.

One of the largest oaks in the British Isles (and possibly in Europe), measuring 13.16m (43ft) in girth, is at Bowthorpe, near Bourne, on the flat Lincolnshire fens. With a hollow inside that measures 2.7 x 1.8m (9 x 6ft), it has been described by tree enthusiast Thomas Pakenham as ‘a cave with branches growing from the roof’. It was apparently hollow nearly 200 years ago, when it was described thus: ‘Ever since the memory of older inhabitants or their ancestors [it has] been in the same state of decay. The inside of the body is hollow and the upper is used as a pigeon-house.’ A floor was installed in 1768 and benches added around the inside, so that the squire of Bowthorpe Park could dine inside with 20 guests. Estimates of its age vary widely from 500 to over 1,000 years old.

The vast hollow trunk of the Bowthorpe Oak. In the eighteenth century a door was cut into it and a floor and benches installed.

In Moccas Park in Herefordshire, the ancient pollarded oaks, fondly called the ‘crusty old men of Moccas’, were described in 1876 by the clergyman and diarist Francis Kilvert (1840–79) as ‘grey, gnarled, low-browed, knock-kneed, bowed, bent, huge, strange, long-armed, deformed, hunch-backed, misshapen oak men’. A number of these trees are also believed to be approaching 1,000 years old, especially the hunched and squat Old Man of Moccas. This park is home to the extremely rare Moccas beetle (Hypebaeus flavipes), which needs the presence of oaks that are at least 600 years old, and flowering hawthorns, to complete its life cycle.

The Pontfadog Oak in Wales is one of Europe’s oldest and largest sessile oaks.

Probably the most famous ancient oak in the British Isles, however, is the Major Oak, which stands in Sherwood Forest and takes its name from the local antiquary Major Hayman Rooke. Although neither the biggest nor the oldest oak, local people feel that it is very special indeed. Possibly the result of pollarding, and with some of its widest branches supported by 3m (10ft) posts, it is a very grand old tree, measuring 3.37m (11ft) in diameter. Alan Mitchell believed it to be only 480 years old, and it may well be that this is close to its true age. It now appears that it grew for much of its life in the open, away from other competing woodland species, which may have allowed it to reach a larger girth in less time than would have been the case had it been in deep woodland. It was beneath – some people say inside – this tree that the legendary Robin Hood (c.1250–c.1350), defender of the poor, is said to have met with his ‘merry men’. This is unlikely, however, as the Major Oak is now considered to be 500–700 years old by most oak experts.

The tree commonly known as William the Conqueror’s Oak, meanwhile, is one of several hundred ancient pollarded oaks known affectionately by their traditional name of ‘dodders’, which still stand in the Great Park of Windsor Castle and date from the Middle Ages. Today it has a circumference of 8.2m (27ft) and an enormous hollow in its trunk, which is said to have been large enough, in 1829, for 20 people to stand in, or 12 to ‘sit comfortably down to dinner’. A tree known as Herne the Hunter’s Oak, also in Windsor Great Park and dating from the thirteenth century, was mourned by Queen Victoria when it was blown down in 1863. Herne the Hunter was an oak god of southern Britain, whose spirit, with horns like antlers, was said to haunt Windsor Forest.

As when, upon a trancèd summer-night, Those green-robed senators of mighty woods, Tall oaks, branch-charmèd by the earnest stars, Dream, and so dream all night without a stir.

JOHN KEATS (1795–1821), ‘HYPERION’

Possibly the oldest oak tree in the park and in the UK is King Offa’s Oak, which also stands in Windsor Great Park. It is a magnificent crumbling ruin of a tree with a massive hollow and a colossal fallen branch stretching away from the trunk. The bark and exposed timber provide surfaces on which mosses and lichens now grow, adding to the combination of browns, russets and copper-greens that light up this very beautiful tree. Ted Green of the Ancient Tree Forum, who has spent years working among the ancient oaks at Windsor, refers to this tree as ‘the mother of all British oaks’ and believes it is probably 1,300 or maybe even 1,500 years old.

The Major Oak in Sherwood Forest is one of the most visited oaks in Europe because of its associations with Robin Hood.

Words of strength and truth

In many different languages, the word for ‘oak’ sounds remarkably similar. In Scottish Gaelic, for example, the oak is ‘dharaich’, while in Manx it is ‘daragh’. In Old Irish it is ‘darach’, in Welsh it is ‘derwen’ and in Greek it is ‘drys’ or ‘dru’. The words are all related, linked by the ‘d…r…’ sound. They appear to come from the same root and to be linked to the ancient Indo-European (Sanskrit) word base ‘deru’, which means ‘oak’ and ‘tree’ as well as ‘firm and steadfast’.

The English word ‘tree’ is related also to this word ‘deru’. So indeed is the word ‘Druid’; for Druids, oaks were magical and a source of wisdom. ‘Deru’ also gave rise to the words ‘trust’, ‘tryst’, ‘troth’, ‘betrothe’, ‘truce’, ‘trow’, ‘durable’ and ‘endure’. We use words that have their roots in ancient proto-languages, unwittingly it seems, when there is something profound – such as trust, strength, or endurance – to talk about.

This thousand-year-old oak, the Judge Wyndham Oak, stands behind the church in Silton, Dorset,

Other ancient oaks in Britain include the Marton Oak in Cheshire, still flourishing but with a gap (formerly containing a calf shed) of 2.4m (8ft) separating the two remaining fragments of trunk, and measuring some 13.4m (44ft) in girth; the Billy Wilkins Oak in Dorset, said to measure 12m (39½ft) around its trunk, which is covered with burrs; the Judge Wyndham Oak, also in Dorset, which is a fraction under 10m (just over 33ft) round; the Old Man of Calke in Derbyshire which is one centimetre over 10m round (at 1.5m), and the giant sessile oak at Pontfadog in Wales, which has a knobbly circumference of 13.38m (44ft). This is possibly Europe’s largest sessile oak.

The remains of the Cowthorpe Oak in South Yorkshire, UK, are still visible nearly 100 years after its demise.

Some giant British oaks were so remarkable while they were alive that they are still remembered long after their demise. The Cowthorpe Oak, for example, which stood in South Yorkshire, was recorded as being larger than any living sessile or common oak today. Langdale’s Topographical Dictionary of Yorkshire (1822) records: ‘This oak in Yorkshire attracted many visitors on account of its age, its girth and its history … the circumference of which, close by the ground, is 60 feet.’ Although the tree collapsed nearly 100 years ago, the local people decided to leave the fallen timber to weather gracefully and serve as a reminder to this once colossal tree. The nearby church contains many words written in appreciation of the tree, including: ‘Still let this massy ruin, like the bones of some majestic hero be preserved unviolated and revered’ (J. G. Strutt, Sylva Britannica, 1822).

Many other great oaks are remembered in place and pub names, such as the Damory Oak in Blandford Forum, Dorset. It was reported that after the great fire of Blandford Forum in 1731, two families lived inside the hollow of this giant. Recorded as 20.7m (68ft) in circumference and with ‘room for 20 men inside’, it was eventually chopped down for firewood in 1755, which raised the sum of £14 (around £1,200 today). The Damory Oak pub sign shows children playing around this great tree.

The Ivenack Oak in Germany is possibly the largest oak in volume in Europe and is estimated to be around 800 years old.

Still let the massy ruin, like the bones of some majestic hero be preserved unviolated and revered.

J. G. STRUTT, SYLVA BRITANNICA, 1822

Many of the oldest examples of particular species of trees live in stressed conditions and/or at the very limit of their range. The largest baobab tree, for example, is also almost the most southerly baobab in Africa, and the bristlecone pines on north-facing slopes have been shown to be able to live for 2,000 years longer than those enjoying the longer, warmer growing seasons of the south-facing slopes. With this in mind, it is not unreasonable to assume that a large oak growing almost at its most northerly extreme, exposed to bitterly cold conditions, could be extremely old.

The tree believed to be the largest oak in Europe is the Kvill Eken or Rumskulla Oak growing near the village of Vimmerby in Sweden. It has a huge girth of 14m (46ft) when the tree’s many burrs are included and is still living today, with a maximum estimated age of over 1,000 years old. However, two great oaks in Denmark may be even older. The largest is the Kongeegen, or King’s Oak, which has a diameter of 3.6m (12ft) and a girth of 14m (46ft) but is in an advanced state of decline with only sparse foliage on top of its vast trunk. It stands in the forest of Jaegerspris Nordskoven and is estimated, even by the more conservative of tree experts, to be between 1,000 and 1,400 years old, making it probably Europe’s oldest living oak. Another oak found in the far north is the Stelmužė Oak in Lithuania, which was thought to be 1,500 years old but it is now considered much more likely that it is less than 1,000 years old.

The Kongeegen (King’s Oak) in Denmark is believed to be the oldest oak in Europe.

Some truly fantastic oaks with fascinating histories can be found in many other European countries, including France and Germany. In France we find the Chêne de Tronjoly, said to be nearly 1,000 years old, which stands on a farm in Brittany. It has a magnificent spreading crown and a bole that has split into two parts, and measures 3.9m (12¾ft) in diameter (or a combined circumference of 12.6m (41¼ft). Possibly contemporaneous with it, the exact age of the Allouville-Bellefosse Oak, near Yvetot, is not known. However, it has been a place of devotion for about 300 years – its massive hollow trunk (which measures 3.8m/12½ft across) having had a chapel and a hermit’s refuge cut into it. Two other large pedunculate oaks are found close to the church in Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, one of which has a girth of 12.5m (41ft).

Possibly the oldest oak in Germany (still alive, though very decayed) is to be found in the village of Erie, near Raesfeld in Westphalia. It is known as the Feme Eiche, or Trial Oak, since public meetings and trials were at one time held beneath it. This oak’s age has been put, by some, at 1,500 years old, but is more likely to be between 600 and 850 years old. Near the village of Ivenack, north of Berlin, however, a grove of majestic oaks still stands. The trunk of the largest tree ascends for 7.6m (25ft) before the first branch occurs, and measures 12.4m (40½ft) in girth at 1m (3¼ft) from the ground. A sign nearby claims that it is 1,200 years old. Experts now believe it to be closer to 800 years old, but what is not in doubt is that it is the largest oak in volume in Europe, dwarfing many other ancient oaks including the UK’s colossal Fredville Oak in Kent.

The more ancient the oak, the more species of insects, fungi and lichens it can support.

Many tree-lovers have a romantic notion of a time when Britain and much of Europe was covered by a vast, almost continuous closed-canopy forest dominated by majestic oak trees. However, recent research suggests that the history of British forests is much more complex. ‘The Holocene forest was probably patchier than we thought: open areas were of local significance and an important feature of the landscape’ says Dr Nicki Whitehouse, a palaeoecologist at Queen’s University Belfast, who examines fossils to reconstruct past ecosystems.

Together with Dr David Smith, a specialist in environmental archaeology at the University of Birmingham, Dr Whitehouse has been looking at ancient beetle remains in an attempt to get a better understanding of the past. Beetles are useful because their remains are quite distinct from one another and many species have associations with very specific habitats. Some beetles, such as dung beetles, are indicative of open areas because they require the dung of grazing animals to survive, whereas others are dependent on rotting wood found in dense, closed-canopy forest.

By studying beetle remains, they found that the insect fossils from between 9500 and 6000 BC were mostly from beetle species associated with open woodland and pasture. There is evidence to support the theory that at this time the presence of large ungulates such as aurochs, wild horses and tarpans led to a dynamic mosaic of forest and open areas. And it is possible that the over-predation of the large grazers by humans then led to a subsequent expansion of forest areas. This may be why, between 6000 and 4000 BC, the beetle fossils changed to those species more associated with closed-canopy woodland. Perhaps this was the golden age of trees that is set so deeply in the psyche of modern people.

One of the theories suggested for this wood temple is ‘excarnation’, during which bodies of the dead may have been exposed on the central upturned oak trunk.

However, by 4000 BC, it is thought that a huge change started to take place as humans began to develop an agricultural way of life, particularly with regard to the keeping of livestock. Neolithic people and their grazing animals helped return the landscape to a mosaic of pasture and woodland again by using grazing regimes and a land-management system that is known as ‘wood pasture’. These open and closed areas provided good grazing as well as timber and non-timber products. This was a bonus for oaks, which prefer to grow on the edge of dense forest or in the open: the openings would have allowed more light in and the grazing animals would also have restricted the competition of the shade-tolerant species in the understorey. Unfortunately, with the expansion of the human population in Europe, agricultural practices lead increasingly to forest reduction and serious fragmentation, a process that has continued to the present day.

Ancient oak mystery

The theory that the oak was a special tree to our ancestors, connected with the supernatural, was strengthened in Britain in 1998. On the north Norfolk coast an extraordinary, mysterious structure was revealed by the shifting sands: an enormous oak tree stuck into the ground, with the stumps of its roots pointing upwards, surrounded by an oval ring of 54 oak trunks. This unique find, which may be the remains of an early Bronze Age tree temple, has been carbon-dated at 4,000 years old, making it as old as Stonehenge.

A patchwork of woodland and open areas, as well as dense forests dominated by oaks, once stretched across large areas of Western Europe, shaping the lives of prehistoric peoples. To Norse and Germanic peoples and to the Celts, the oak was a sacred tree, and it was among holy oak groves that they made contact with their powerful gods.

A connection between the oak and ancient European storm gods developed long ago. Oaks are in fact more likely to be struck by lightning than most other European woodland trees, because of their size and because their electrical resistance is low. Belief in such a connection appears to have been common to the Aryan peoples who came to inhabit much of Europe and parts of Asia before the birth of Christ. To these people, the mighty oak formed a channel through which the power of the sky gods could reach the mortals on Earth – visibly demonstrated when a tree was struck by lightning and caught fire.

The kindling of fire from an oak log on midsummer’s eve was a Celtic practice associated with fertility and probably accompanied by human sacrifice. Oak was also traditionally used for the Yule log that was burnt at the winter solstice, in the hope of drawing back the sun to warm the Earth. (In Rome, the Vestal Virgins – priestesses of Vesta, the Roman goddess of the hearth – also used oak wood for their perpetual fires.)

The oak tree occupied a central position in the religious practices of the Celtic priests, the Druids. Though other interpretations are possible, the name ‘Druid’ has been translated as ‘oak wisdom’ and is said to derive from the Greek and Sanskrit words for oak, deru. The Druids revered the tree, as they believed it embodied the strength, power and energy of their mighty god Esus, and ritual sacrifices in his honour were performed amid their sacred groves. Mistletoe, a semi-parasitic shrub that can cling to the oak’s branches under the right conditions, was also regarded as sacred, since it was thought to be a guardian of the tree.

A carved representation of the ‘Green Man’ garlanded with oak leaves, inside Sutton Benger Church, Wiltshire, England.

Germanic tribes dedicated the oak to Donar, while in Norse mythology, the oak was sacred to Thor, who drove his chariot across the heavens and controlled the weather. Both were gods of thunder, and if a tree was struck by lightning, pieces of the splintered wood were kept as protective charms. At the end of the first century AD the Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus (c.55–120) mentions oak groves in north-west Europe that were especially sacred to Thor, many of which were subsequently destroyed by Christian missionaries. Belief in this deity was so strong that ‘Thor’s day’ – now Thursday – was dedicated to him right across the Germanic world and regarded as a holy day.

The oak was likewise revered by the Ancient Greeks and Romans. The tree became sacred to the Greek god Zeus, the supreme being associated with the sky and weather, and to the principal Roman god Jupiter – the oak’s association with lightning strikes, which were the special weapons of both these deities, was particularly significant.

To the ancients, the oak tree’s special presence and powers included those of an oracle. In Homer’s Iliad, Odysseus travelled to the famous oak that grew at Dodona to find out from its ‘lofty foliage’ the plans of Zeus. And according to the Greek poet Hesiod’s Catalogues, the priestesses, who took the form of doves and lived in the tree’s hollow trunk, imparted ‘all kinds of prophecy’ to those who travelled there.