BOTANICAL NAME

Castanea sativa

DISTRIBUTION

Southern Europe, western Asia, North Africa.

OLDEST KNOWN LIVING SPECIMEN

The Tree of One Hundred Horses, Sicily: recorded in 1770 to have a bole measuring 62m (204ft) in girth. Today, the two largest remaining pieces measure 6m (18ft) in diameter at 1m (3ft) from the ground. Estimated age: 2,000–4,000 years.

MYTHICAL SIGNIFICANCE

The Tree of One Hundred Horses is believed to have sheltered the Queen of Aragon and her retinue of 100 cavaliers from a rainstorm in 1308.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not classified on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Part of an avenue of ancient sweet chestnuts at Croft Castle, Herefordshire, England.

In 1308 Giovanna, Queen of Aragon, was on her way to view Mount Etna, Sicily’s famous volcano, when she was surprised by a sudden rainstorm. Luckily for her and her escort of 100 cavaliers, they found themselves in the vicinity of a most extraordinary tree – one that was already famous for its colossal proportions and was apparently old at the time of Plato, the Greek philosopher (c.428–348 BC), some 1,700 years previously. The tree was a sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa), and so huge was its canopy of leaves and branches that Queen Giovanna and her entire retinue – so the legend goes – were able to shelter beneath it. This incident gave rise to the name by which this tree (which still survives in part) is known today: Castagno dei Cento Cavalli, or Tree of One Hundred Horses.

Situated near the village of Sant’Alfio, on the eastern slopes of Mount Etna, at about 550m (1,800ft) above sea level, the Tree of One Hundred Horses is considered to be the largest tree – in stoutness at least – ever recorded. In 1770 its bole was found to be an astonishing 68m (204ft) in girth. Like Europe’s most ancient limes, oaks and yews, this chestnut had also become hollow in extreme old age. In 1670 the hollow was apparently so large that flocks of sheep were penned inside it. Some time later, a local family was also reported to be living inside the massive tree. Although by this time the chestnut had the appearance of a group of trees growing together, excavations carried out over 200 years ago showed that all the parts were joined to a single root. By 1865, the tree had split into five distinct sections, of which today three separate pieces survive, 3.5–4.5m (12–15ft) apart. Though damaged, this once gargantuan chestnut – when in full leaf – still looks very much alive.

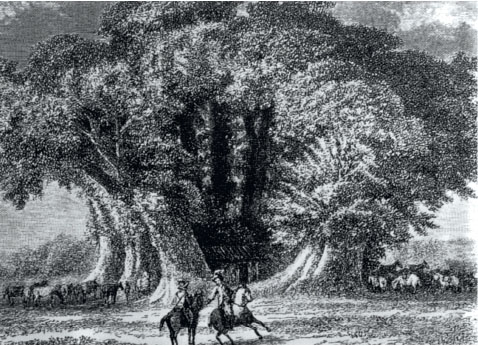

The Tree of One Hundred Horses (Castagno dei Cento Cavalli) as depicted in 1784.

It would appear that the sweet chestnut’s general decline (over the last few hundred years) has been provoked largely by the activities of people, within or around it. While the Tree of One Hundred Horses has recently been fenced to protect what remains, an engraving dated 1784 clearly shows a dwelling of some sort inside the tree, with pack animals tethered outside. One such hut was fitted with a kiln for drying the sweet chestnuts produced by the tree – an activity that cannot have been beneficial either to the roots or the living wood. Firewood was also apparently chopped from the tree.

The true age of the Tree of One Hundred Horses is difficult to establish, but it is generally considered to be 2,000–4,000 years old. That it should have survived the volcanic activity of the island for so long (it is only 8km [5 miles] from Mount Etna’s crater) is indeed remarkable.

Early in the twentieth century, the slopes of Mount Etna were still graced by large numbers of sweet chestnuts, which formed ‘dense forests’, according to Mrs Grieve, whose famous herbal was published in 1931. Though none may be as old as the Tree of One Hundred Horses, other ancient sweet chestnuts survive nearby. The largest, with a diameter of 6.2m (20½ft), is located about 0.8km (½mile) away at Mascali, and is known as the Castagno della Nave or Ship Chestnut, because of its sheer size.

The Tree of One Hundred Horses today. Although the tree has split and now consists of three large separate trunks, it still produces large quantities of nuts each year.

Herbal remedies

Medicine has long made use of extracts from the toothed, leathery leaves of the sweet chestnut, especially for coughs, catarrh and whooping cough, and also for diarrhoea. The famous English herbalist, physician and astrologer Nicholas Culpeper (1616–54) recommended taking chestnuts to thicken the blood. Throughout Europe the nuts themselves were traditionally carried as medicinal charms and were viewed as being therapeutic for many aches and pains, including rheumatism.

The Chestnut of the Green Lizard in Calabria is considered to be Italy’s largest intact sweet chestnut today.

Possibly first domesticated in western Asia, sweet chestnuts are native to the deciduous woodlands of southern Europe ( south of the Alps), and trees of great age and size, with girths of around 12m (39½ft), are to be found across the continent.

On the Italian mainland there are a number of enormous ancient chestnut trees. The one considered to be the largest complete tree in Italy today – in terms of its overall dimensions – is growing at Il Monte, near the village of Grisolia in northern Calabria. The survivor (along with two other smaller trees) of a grove of ancient chestnuts, it measures 4.3m (14¼ft) in diameter and is called, in the Calabrian dialect, the Castagna del Salavrone or Chestnut of the Green Lizard.

Possibly the largest tree in France – regarding the width of its bole at least – grows near the town of Pont l’Abbé in Brittany. This ancient tree, said to be 1,000 years old, measures just over 4.8m (16ft) in diameter at its base. Another vast French chestnut, standing on the southern shore of Lake Geneva near the town of Maxilly, close to the castle of Neuve Celle, is said to have sheltered a hermitage in 1408. The island of Corsica also has many ancient chestnuts, including the tree believed to be 1,000 years old still growing at Levie.

In Spain, the striking Castaño Santo or Holy Chestnut in the Sierra de las Nieves near Ronda in Andalucia, which has a girth of some 13m (42½ft) and an estimated age in excess of 800 years, has been declared a national monument and is a popular tourist attraction.

According to the Woodland Trust’s Ancient Tree Hunt, completed in 2011, there are 19 enormous sweet chestnuts in the United Kingdom that are over 10m (33ft) in girth. Some of these can be discounted because they are multi-stemmed trees, but the Canford Chestnut, which stands in the grounds of Canford School in Dorset, the fourth largest chestnut in the UK, is a fraction over 13m (42½ft) around the trunk at breast height, while the largest surviving tree of what are known locally as the Three Sisters, in North Wales, is 12.7m (41½ft). However, the Tortworth Chestnut in Gloucestershire is probably the oldest in the UK today. Records show that this veteran was a prominent tree and boundary-marker as long ago as the twelfth century, and a legend suggests that it may have been planted around 800 AD during the reign of King Egbert. A plaque near the tree, dating back to 1800, reads:

May man still guard thy venerable form, From the rude blasts and tempestuous storm, Still mayest thou flourish through succeeding time, And last, long last the wonder of the clime.

The Tortworth Chestnut is believed to have been planted in 800ad. Written records of the tree go back as far as the twelfth century.

The largest of the ‘Three Sisters’ in North Wales with a girth of 12.7m (41½ft).

Uses of chestnut wood

In Britain today the sweet chestnut is grown commercially only for its timber. A vigorous, fast-growing tree, it responds well to coppicing, producing a good crop every 12–30 years.

In the past, sweet chestnuts were planted and coppiced in south-east England for charcoal manufacture, which was used extensively in metalworking. Kent and Sussex are the major areas for chestnut coppices today, and thousands of hectares are managed commercially.

Young sweet chestnut wood is hard, strong and rich in tannins, making it suitable for outdoor use. It is much valued for stakes, gateposts and paling fencing, which will last for 20 years or more, and for outdoor cladding (shingles) on buildings.

Sweet chestnut bark has been an important source of the vegetable tannin used for tanning leather in many European countries, including the UK, for many years. Italy is a major exporter.

In Italy, chestnut wood is also used to make barrels for ageing balsamic vinegar.

Chestnut coppice is a familiar sight across parts of Europe. Trees are cut every few years to produce poles and timber for fencing and charcoal.

Today, though only a relic of its former self, with three huge branches resting on the ground, parts of the Tortworth Chestnut are still alive and flourishing.

The Romans are generally credited with introducing sweet chestnut trees to the British Isles, largely because of the finds of husks and nuts that have been made in a number of locations, including Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland. However, this may indicate only that chestnuts were one of the foodstuffs much favoured by the Romans, which were imported from Italy during the time of their occupation of Britain.

The sweet chestnut is well known for its vigorous growth and is therefore particularly suitable for growing as a coppiced tree. Its bark, purplish-grey in early life, becomes dark brown and deeply fissured with age, forming angled spirals of heavy ridges, or a network of ridges, when it is several hundred years old. Throughout its long life the glossy, dark green leaves of the tree are a characteristic feature, with their prominent parallel veins, each ending in a spiny ‘tooth’. The fruits are also distinctive: sharp-spined, yellow-green husks that split open in the autumn, usually to reveal two shiny red-brown nuts.

Unlike most other commercial nuts, which contain relatively large quantities of protein, sweet chestnuts consist of up to 70% starch, 5% fat and 4% protein.

‘Delicacies for princes and a lusty and masculine food for rusticks, and able to make women well-complexioned.’ This is how the British writer John Evelyn (1620–1706) described the noble fruit of the sweet chestnut. Evelyn lamented the fact that in England sweet chestnuts were chiefly fed to pigs, whereas they had been much loved by the Romans and were widely consumed across southern Europe and into Asia. In parts of Italy and on the island of Corsica, sweet chestnuts were a staple food for millennia, largely replacing cereals. They were in fact once used as a currency in Corsica and still form an important part of the local cuisine. They appear in a great variety of foods – from a type of polenta to local beer, soup and ice cream.

Sweet chestnuts are generally eaten roasted or boiled, but can also be processed to produce flour, bread, porridge, stuffing for poultry, fritters and delicacies such as the famous marrons glacés of France. They contain relatively low levels of protein and fat, but very large quantities of starch. For this reason, they were once widely used for whitening cloth.

Chestnuts remain an important part of people’s diets across southern Europe, and it is still a popular weekend pastime in the autumn to collect them.