BOTANICAL NAME

Adansonia digitata and other species.

DISTRIBUTION

A. digitata: most of the African continent and Madagascar. Madagascar only: A. grandidieri, A. madagascariensis, A. perrieri, A. rubrostipa, A. suarezensis, A. za. Northern Australia only: A. gregorii.

OLDEST KNOWN LIVING SPECIMEN

The baobab with the largest diameter was the Glencoe Baobab in South Africa until 2009, when it measured 15.9m (52ft) in diameter at breast height. It was estimated to be at least 3,000 years old. The largest living baobab in volume today, and probably the oldest, is at Sagole in northern South Africa, and is 13.7m (45ft) in diameter and 47m (154ft) in circumference.

RELIGIOUS SIGNIFICANCE

Considered holy in some places, and also to be the home of important spirits.

MYTHICAL ASSOCIATIONS

Numerous, relating to its origin (how it came to be the upside-down tree) and its powers.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Classified on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as follows: A. digitata: not classified; A. grandidieri: endangered (2006); A. madagascariensis: threatened (2011); A. perrieri: threatened (2011); A. rubrostipa: near threatened (2011); A. suarezensis: endangered (2011);

A. za: near threatened (2011).

Adansonia grandidieri is the largest and most striking of all the baobab species in Madagascar.

Rising out of the savannah grasses with its broad, grotesque trunk and squat stature, Africa’s most famous and distinctive tree – the baobab – is a magnificently arresting sight. Often wider than it is high, and with root-like branches that are devoid of leaves for large parts of the year, the ‘upside-down tree’, as it is sometimes affectionately known, seems an entirely appropriate name for this curiosity.

First described by a European in 1592, in Prospero Alpini’s De plantis Aegypti liber (Natural History of Egypt), the most common species of baobab, Adansonia digitata, astonished viewers over 400 years ago. Growing over a large proportion of the African continent, this baobab – which is also known as Judas’s bag and the monkey-bread tree – occurs as far north as Sudan and as far south as Northern Cape province in South Africa, and from the Cape Verde Islands in the west to Ethiopia and Madagascar in the east. Altogether there are eight species of baobab: six of them occur only on the island of Madagascar, while one other species grows only in northern Australia.

It is easy to see why baobabs in Africa are sometimes referred to as ‘vegetable elephants’.

A Caliban of a tree, a grizzled, distorted old goblin with the girth of a giant, the hide of a rhinoceros, twiggy fingers clutching at empty air.

HILARY BRADT, GUIDE TO MADAGASCAR

The largest authenticated baobab alive today in total volume stands at Sagole in the Northern Cape province and measures an astounding 13.7m (45ft) in diameter. However, the record for the largest diameter was held by the Glencoe Baobab, which had a vast trunk measuring 15.9m (52ft) until it split in 2009. The current record holder for diameter, according to the South African Dendrological Society, is the Sunland Baobab, located in Limpopo province, which has a diameter of 10.64m (35ft). At 22m (72ft) high, and with a circumference of some 47m (154ft), this baobab is slightly smaller, overall, than the Sagole tree. Radiocarbon dating has suggested that this giant may be up to 6,000 years old, and that there have been regular fires in its hollow trunk at least as far back as the year 1650. The enormous hollow inside the Sunland Baobab was turned into a pub and wine cellar in 1993 and has since become a popular tourist destination.

Some experts now believe that it is entirely possible that even larger trees existed in the past. An interesting feature of the baobab, which can make the precise recording of its dimensions more challenging, is that its trunk may fluctuate in size between seasons, as water is stored or used up.

The French botanist Michel Adanson (1727–1806) ascribed ages to some of the trees he had seen that were considered by many to be sacrilegious. His greatest estimate for an individual tree was 6,000 years. This implied that it must have begun life before the great flood of the Old Testament, then commonly believed to have taken place only 4,000 years before. Most scientists of the time disagreed with Adanson’s calculations, but recent studies of tree rings and carbon-dated material taken from living trees have demonstrated that baobabs can indeed live to very great ages. A tree with a girth of just 4.5m (14¾ft), for example, has been shown to be over 1,000 years old. While the exact ages of most of the greatest baobabs of Africa have not been calculated, estimates based on the above information point to ages of more than 4,000 years for some. Research into the ages of the boab tree of Australia (A. gregorii) suggests that it too can reach ages in excess of 2,000 years. In the absence of scientific studies, the true ages of most of Madagascar’s baobabs can only be guessed at. However, we know – from studies of the great ages reached by bristlecone pines and yew trees, for instance – that challenging growing conditions can produce trees of great age, if not great size, and thus some relatively small baobabs could still be immensely old.

A large double-trunked baobab standing in the savannah grasslands of Namibia.

The botany of Africa’s most common baobab (A. digitata) is fascinating. It is not usually a tall tree, reaching only 14–23m (45–75ft) in height, but it is famous for its gigantic girth. The main trunk is generally cylindrical in shape and suddenly tapers into a number of comparatively small, thin, spreading branches. Baobabs are deciduous trees and new foliage usually appears in late spring or early summer. The leaves of A. digitata take the form of five to seven leaflets, which look like fingers on a hand, giving rise to its botanical term ‘digitata’. They produce large, sweet-scented white flowers, some 13–18cm (5–7in) wide, which are pollinated by a variety of nocturnal creatures, including bats and bushbabies. The egg-shaped fruits that form are covered with a green velvety skin, which makes them look rather like velvet purses dangling from the branches. The thick, woody shell of the fruit encases a pulpy white flesh in which a number of black seeds are set. This edible fruit is particularly relished by baboons, giving rise to one of the baobab’s popular names: monkey-bread tree.

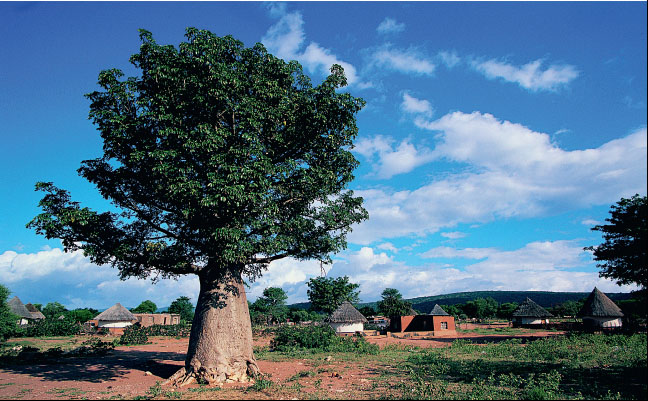

Baobab trees are a feature of many African villages, where they provide shade, fibre for rope and fruit rich in vitamin C.

To many of the native peoples of Africa the baobab has not simply been a familiar feature of the savannah landscape but, literally, a ‘tree of life’. Its special ability to store water during droughts has enabled many settled communities and nomadic peoples to survive, even though they may be far from any river system. Over thousands of years, the distribution of these strange trees has facilitated the expansion of great African nations such as the Bantu.

The baobab’s enormous trunk acts as a water-storage organ: the largest baobabs can contain more than 136,000 litres (30,000 gallons) of water. Many African peoples learnt long ago how to make use of this all-important feature. The Kalahari bushmen, for example, have traditionally used the hollow stems of grasses joined together, like straws, to reach the water inside the trunk, from where it can be sucked out. In Sudan, however, some large baobab trunks are deliberately hollowed out so that they will collect rainwater during the rainy season.

Baobab trees like these in Mali are distinctive in that they have no leaves for much of the year, which is why they are sometimes called ‘the upside down tree’.

The baobab is remarkable not only for its water-storing properties: it also provides a number of very useful products that have become central to the way of life of numerous people. Once the bark has been cut away from the trunk, an inner bast layer is revealed that yields a strong fibre used for making ropes, sacks and nets, and which is even woven to make cloth. Other uses include the strings for musical instruments and waterproof hats. Fortunately, baobabs have a remarkable ability to regenerate and can survive the removal of large areas of bark.

The vast hollows that develop inside the trunks of many ancient baobab trees have been put to many uses including prisons, grain stores and even a bar.

The egg-shaped fruits of the baobab have been a traditional source of nutrition. The woody shell encloses seeds set in a fleshy pulp, both of which can be eaten. The pulp has a pleasant, tart flavour and, when dried, can be mixed with water to make a refreshing drink. The fruit contains citric and tartaric acids, which are important to the diet of nomadic peoples. These acids have also been used by herding peoples in Africa to coagulate milk, and commercially to coagulate rubber.

‘We were lost in amazement, truly, at the stupendous grandeur of this mighty monarch of the forest … The dimensions of which we took with a measuring tape proved its circumference at its base to be twenty-nine yards. It had shed all its leaves (this was winter), but bore fruit from five to nine inches long, containing inside a brittle shell seeds and fibres like those of the tamarind, enclosed in a white acetic powder … which mixed with water makes a very pleasant drink.’

JAMES CHAPMAN, TRAVELS IN THE INTERIOR OF SOUTH AFRICA (1868)

The baobab’s seeds – which are high in protein and oil – are generally either eaten on their own or mixed with millet to form a kind of gruel. They may also be pounded into a paste, like peanut butter, or traded for the extraction of their oil. Other parts of the tree that are edible include the young shoots put out by germinating seedlings, which are eaten like asparagus. Young leaves are also sometimes used in salads and provide important fodder for domesticated and wild animals alike. In Northern Cape province, in South Africa, caterpillars that live on the baobabs are also gathered as a food by the local people.

The trunk of the baobab tends to become hollow with old age, but in some areas people have assisted nature by hollowing out the trees themselves. Many ancient trees have considerable cavities of this kind inside them and, over the centuries, some extraordinary and ingenious uses have been made of this feature. The hollow inside the tree has proved to be an ideal place to store grain, water or even livestock, while people have even been known to set up home in larger baobabs. In Senegal, many hollows have been used as municipal buildings, sometimes with the badges of office carved into the outer trunk.

Large baobab trees near villages are considered important by local people, who often believe that they provide a meeting place for the ancestors and other spirits.

A tree that fights fevers

Baobabs have a long history of use, over thousands of years, for medicinal purposes. In some parts of Africa their bark is still used for the treatment of fevers and, for a time in Europe, it was used in place of cinchona bark (the source of quinine) in order to fight malaria. Because they are rich in vitamin C and calcium, the leaves and fruit also act in a preventative capacity against certain illnesses. Baobab pulp is burnt in some areas so that the smoke will fumigate the insects that live on domestic cattle.

It is not surprising that a tree of such imposing stature as the baobab, and one that has become so important to so many different cultures, should have become the focus of numerous myths, legends and superstitions. A large number of beliefs about the baobab were collected by anthropologists and explorers at the beginning of the twentieth century. In both East and West Africa it was noted that mischievous spirits were believed to reside in the trees. In the Northern Cape province of South Africa, for example, it is still believed by some that spirits inhabit the large, white flowers and that anyone who plucks them will be eaten by a lion. In Senegal and Gambia, a tradition of placing the dead bodies of poets, musicians and ‘buffoons’ inside baobabs was also recorded. These people were believed to be possessed by demons and could therefore cause bad luck to befall crops or fisheries if they were buried in the ground or at sea. In Burkina Faso, the West African writer Seydou Dramé witnessed and wrote about the funeral of a baobab, noting that: ‘Not all trees have a right to such treatment. The only ones are those that have played an important role in the life of the village, providing a resting place for local gods and a secret meeting place for the ancestors.’

The following legend, of which there are numerous variations, comes from the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro in Kenya. It explains how the baobab came to look as it does today.

A long, long time ago, a baobab stood beside a small pond and raised up its branches towards the sky. It looked at the other trees, whose crowns were covered in flowers, delicate bark and leaves. They shimmered with colour and the baobab saw all of this in the surface of the pond – like a mirror – and became angry. His own leaves were very small and his flowers scarcely visible. He was fat and his bark resembled the wrinkled skin of an old elephant. The tree called up to God and pleaded with him.

However, God had created the baobab and was satisfied with his work because this tree was unlike the other trees. He liked diversity. But he couldn’t bear criticism. He asked the tree if it found the hippopotamus beautiful, and if it liked the cry of the hyena. Then God went back up into the sky to reflect in peace.

The baobab didn’t stop looking at himself in the mirror, or complaining. So God came down again, seized the baobab, lifted him up and replanted him upside down in the earth. After this the baobab no longer looked at himself in the mirror, or complained again. Everything was restored to order.

The giant baobab tree at Sagole in South Africa is probably the widest-trunked living tree, with a girth of 47m (154ft).

Madagascan mystery

It is a curious fact that only one baobab species, A. digitata, is found across the entire continent of Africa, but that this species and six others are found on the island of Madagascar, with a separate species only in Australia. It has been suggested that after Madagascar separated from mainland Africa 150 million years ago, either unusual evolutionary conditions gave rise to the additional five species or that all six species were able to survive because of the lack of large herbivores. Another theory is proposed by Dr A. Baum, Professor of Botany at the University of Wisconsin, who studied the chromosomes and the structure of the flowers of the different species. The results suggested that the genus Adansonia evolved relatively recently – between 7 and 17 million years ago, long after the continents had separated. His theory is that the large seeds, with their waterproof shells, sailed west to mainland Africa and east to Australia on ocean currents. However, the seed pod of A. gregorii (the Australian species) is unique in not having a waterproof shell. Baum explains this as a recent evolutionary change.

The magnificent avenue of Adansonia grandidieri baobab trees in Morondava, Madagascar.