BOTANICAL NAME

Ginkgo biloba

DISTRIBUTION

Some trees surviving in the wild in the mountains of south-western China; now widely cultivated throughout the world as an ornamental.

OLDEST KNOWN LIVING SPECIMEN

Li Jiawan Grand Ginkgo King, near Guiyang, the capital of Guizhou province, China, is around 3,000 years old. It measures about 15.6m (51ft) in girth at breast height.

RELIGIOUS SIGNIFICANCE

Revered by Buddhists in China and Korea, and by followers of Shinto in Japan, the ginkgo was planted as a temple tree in antiquity.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Classified on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2011 as ‘endangered’.

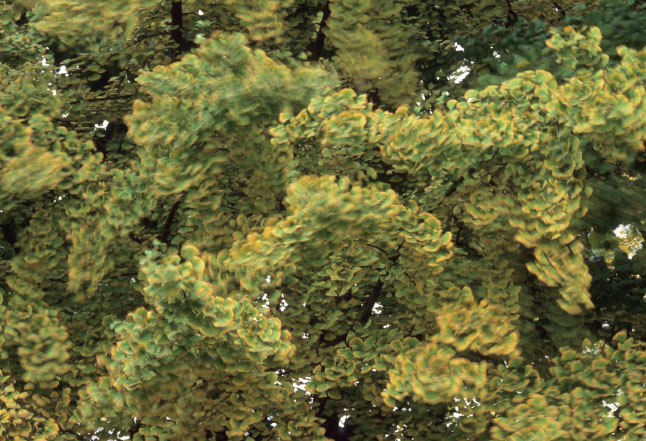

The distinctive two-lobed, primitive leaves of the ginkgo from which the tree takes its scientific name – Ginkgo biloba.

An ancient ginkgo tree is a spectacular sight in autumn. The tallest individuals can reach heights of over 60m (200ft), and in autumn their leaves turn from apple green to a brilliant golden yellow. Against a deep blue Asian sky, this is an awe-inspiring sight, and it is not difficult to understand why the tree was revered by Buddhists in antiquity.

The ginkgo is not only a strikingly beautiful tree, but also unlike any other tree on Earth. It falls into neither of the two main categories of trees – conifer and broad-leaved – but belongs to its very own order (Ginkgoales), of which it is now the only surviving member. The ginkgo is believed by many scientists to have been the very first tree to evolve, as it has just as many similarities with ferns as it does with trees. Western botanists often call it the maidenhair tree because of the striking resemblance of its leaves to those of the maidenhair fern.

The tree has been given various other names, however. In ancient Chinese it was called I-cho (duck’s foot tree) since the shape of its leaves is reminiscent of a duck’s webbed foot. It was also known by the Chinese as the godfather–godson tree, because a tree planted by one generation would begin to produce fruit one or two generations later. However, its most popular name, ginkgo, is the Japanese version of the Chinese ideogram which is pronounced yin-kuo, meaning ‘silver fruit’.

A mature ginkgo in Seoul displaying yellow autumn foliage.

The oldest ginkgo trees are to be found in China, such as this one, the Lengji Ginkgo in Sichuan.

The ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) is a deciduous tree with a graceful grey trunk, which becomes deeply fissured with age. The tree’s small leaves soften its shape, without disguising the elegant branches that rise stiffly from the main trunk. Its leaves are fan-shaped and generally have a small cleft in between the two lobes. The ginkgo is so ancient that its system of leaf veins pre-dates those found in any other living tree.

Another unique feature of the ginkgos – which like most primitive plants can be either male or female – is their method of reproduction. In 1896, as he looked down his microscope at the female ginkgo tree’s ovule, the Japanese botanist Sakugoro Hirase observed for the first time the presence of a motile sperm swimming towards the waiting egg cells. From a scientific point of view, this was a remarkable discovery because motile sperm was considered to be a trait associated with evolutionarily primitive non-seed plants such as mosses and ferns. Ginkgos are clearly seed-producing trees, but here was a feature that linked it more closely to ancient non-seed plants than to the conifers and broad-leaved trees that populate the planet today.

Ginkgo leaves are highly distinctive: their system of leaf veins pre-dates those found in any other tree species.

The order to which the ginkgo belongs – Ginkgoales – can be traced back to the Permian era, almost 250 million years ago, while the genus Ginkgo first appears in the fossil record some 170 million years ago. To date, at least four different species of ginkgo are known to have shared the planet with the dinosaurs, making the tree a true living fossil. It has survived virtually unmodified for the last 150 million years, and it is possible that it was the very first tree to rise from the prehistoric landscape and tower over tree ferns and cycads, the ancient palm-like plants that are native to tropical and subtropical regions. Fossil records show that it was once widespread throughout the world, from China to California and from southern Europe to the island of Spitsbergen in the Arctic Circle; 30 million years ago it still formed extensive stands in the London basin.

In evolutionary terms, the ginkgo has been able to survive the many great changes that have occurred over millions of years – including the attentions of herbivorous dinosaurs and a myriad of other plant-eating organisms that evolved and later became extinct – until relatively recently. The ginkgos that once covered vast areas of the Earth for millions of years have gradually been overtaken by other competing types of tree and by the time the first humans arrived in Asia about 500,000 years ago, its range had shrunk to the Chekiang region of easternmost China and Sichuan in the far west.

For many years it was thought that ginkgos had become extinct in the wild and were only to be found in temple gardens. In the last decade, wild ginkgo trees have been located in remote parts of south-west China.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, and following other plant hunters who had begun to descend upon countries in Asia, Ernest H. ‘Chinese’ Wilson, as he became known, was lured to China by stories of extraordinary plants, such as 1,000-year-old ginkgo trees that were 30.5m (100ft) tall and had girths of 15.25m (50ft). He made two expeditions to China, in 1907 and 1911, amassing 65,000 botanical specimens for Harvard’s arboretum. In 1930, not long before his death, Wilson declared that: ‘[Ginkgo] no longer exists [in Asia] in a wild state, and there is no authentic record of its ever having been seen growing spontaneously … In Japan, Korea, southern Manchuria, and in China proper it is known as a planted tree only, and usually in association with religious buildings, palaces, tombs, and old historic or geomantic sites.’

A giant ginkgo tree in South Korea that is believed to be more than 1,000 years old.

In 1989, nearly 60 years after Wilson’s last expedition, three researchers – Peter Del Tredici from Harvard, Yang Guang, director of Nanjing Botanical Garden, and Ling Hsieh, a Chinese forester – began looking for wild ginkgos on Tian Mu Mountain in China. As they carried out their search in a forest containing a number of large ginkgo trees, it soon became apparent that there were few, if any, young trees. However, what the three did notice was that many of the large old trees were reproducing vigorously from suckers. Aerial roots known as chichi had been observed in ginkgo trees before, but on Tian Mu Mountain they witnessed lignotubers emerging from the base of trees for the first time. Their presence helps to explain how ginkgos can live so for so long, outliving pests and diseases and sending out new sprouts when damaged or stressed.

Recent DNA analyses also support the theory that there are indeed wild populations still surviving in China. Research has shown that isolated ginkgo populations in south-western China, especially around the southern slopes of Jinfo Mountain, have a significantly higher degree of genetic diversity than populations in other parts of the country. It is believed that south-western China may have provided a glacial refuge for ginkgo populations in the wild.

Trees such as the giant ginkgo at Yon Mun temple in South Korea attract thousands of visitors each year.

The largest Ginkgo biloba in the world, the Li Jiawan Grand Ginkgo King, is located about 100 km (62 miles) west of Guiyang, the capital of Guizhou province in China. It stands about 30m (98ft) tall, with a girth of 15.6m (51ft) at breast height. At its widest, the trunk is 5.8m (19ft) wide. The trunk is largely hollow, enclosing an area of around 10–12 sq. m (108–130 sq. ft), which is said to be large enough to seat a dinner party of ten!

The memory tree

In parts of China, the ginkgo is known to traditional doctors as the memory tree because of compounds in the leaves that are believed to enhance brain activity. One of the oldest Chinese medical texts, dating back to 3000 BC, states that ginkgo leaves benefit the brain. Research has shown that a number of terpenes, components of essential oils, which occur naturally in ginkgo leaves, can increase arterial blood supply to the brain.

Chinese researchers have described this giant as a ‘five-generations-in-one-tree’ complex. Such trees occur when a seedling takes root as a tree and then over the course of hundreds, possibly thousands of years – as a result of repeated sprouting in places where a trunk has been damaged or died – a new trunk forms and continues the tree’s growth and development. In the case of the Ginkgo King there are five distinct, partly fused trunks visible. Researchers believe that first-generation trunks may reach up to 1,200 years of age, that second generation stems live for about 1,000 years, and that subsequent trunks decrease in age by 200 years per generation. Using this formula, the maximum age for the Ginkgo King would be around 4,000 to 4,500 years old.

There are a number of other large ginkgos in China, including the Ginkgo Queen, which is reputed to be 2,500 years old. A tree in Lengji, Luding Xian, in the province of Sichuan, is 30m (98ft) tall and has a girth of 12.4m (40½ft) at breast height. It is said to have been planted when Zhu Geliang went on an expedition to southern Sichuan during the period known as the Three Kingdoms, which would make it more than 1,700 years old. Another specimen in Lijiawan, Guizhou province in China is 40m (131ft) tall and has a diameter of 4.71m (15¾ft).

Set in a dramatic mountain landscape, the tallest ginkgo today stands in the grounds of the much-visited Yon Mun temple in South Korea, about 96 km (60 miles) north of Seoul. It is a magnificent and very healthy tree, over 60m (200ft) tall, and displays the ginkgo’s classic conical shape. The trunk is 4.5m (15ft) thick at breast height and the tree is reputed to be 1,100 years old.

Another of the largest ginkgo trees in South Korea measures 13m (42½ft) around the trunk, and is estimated to be at least 800 years old. Local legend records that the tree grew from a stick dropped by a Buddhist priest who stopped to drink the water from a stream. Local people revere this tree, as legend has it that a huge white snake lives inside. Some also believe that there will be a bumper harvest if the tree’s leaves all turn yellow at once. Some large trees also occur in Japan, in Shinto temple grounds, although it is believed that these trees were introduced less than 1,000 years ago. The magnificent Tenjinsama no ichou, for example, which is to be found in Aomori, North Honshu, Japan, has a girth of around 10m (33ft) and is spectacularly festooned with chichi or aerial roots. Today 11.5 per cent of Japan’s street trees are ginkgos. They make ideal urban trees because they are resistant to pollution and disease, and at 100 years old are still flourishing when many other street trees have long since died of old age or disease.

The distinctive shape of the ginkgo leaf has given rise to one of the tree’s popular Chinese names – ‘duck’s foot tree’.

The German naturalist and physician Engelbert Kaempfer provided the Western world with its first description of the ginkgo at the end of the seventeenth century. Ginkgos were then introduced from Japan to Europe in about 1730. Large trees of over 200 years of age can be seen in Britain – the oldest is at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, just outside London, having been transferred there in 1761 from the Duke of Argyll’s estate not far away in Twickenham. After an absence of 30 million years, the ginkgo is once more thriving in the London basin.

Ginkgo biloba is very hardy and will thrive in a wide range of conditions. It is able to tolerate the polluted air of major cities and is highly resistant to pests and diseases. Horticulturalists have been quick to exploit the natural variations that exist, in order to select and breed many ornamental forms. In autumn, the falling fruit of the female tree tends to make the area beneath the tree malodorous, so it is male trees that are generally planted as ornamentals in large cities.

The ginkgo’s leaves and seeds have a very long history of use in traditional Chinese medicine for the treatment of a variety of ailments, including asthma and lung complaints. Stewed ginkgo seeds (the seeds are toxic when raw) are prescribed by modern Chinese practitioners as a general lung tonic and for the treatment of asthma and bronchitis.

Ginkgo leaves blowing in the wind make shapes reminiscent of the frills that decorate the ‘dragons’ that parade in the streets for the Chinese New Year.

While the seeds feature most prominently in the ancient Chinese materia medica, it is the active compounds contained within the leaves that have given rise to ginkgo’s fame in more recent times as a possible treatment for several medical conditions. Ginkgo extracts are now worth millions of dollars annually, and, in the form of supplements, are among the best-selling herbal medicines in Europe. Much recent research has been prompted by the discovery that ginkgo improves blood circulation by dilating blood vessels and reducing the stickiness of blood platelets, and can therefore improve the flow of blood to the brain. As a result, ginkgo has been widely prescribed in Europe for a whole range of ailments that might benefit from increased blood flow, from senile dementia, tinnitus and memory loss to chilblains and Raynaud’s disease. Opinion is divided, however, as to the real benefit of ginkgo in this regard. While some studies have shown that ginkgo may have a positive effect on memory in people with Alzheimer’s disease, several studies have found that ginkgo was no better than a placebo in reducing the symptoms of Alzheimer’s or actually preventing it, and no better than a placebo in relieving tinnitus.

To meet the world demand for ginkgo products for the pharmaceutical industry, China has promoted the cultivation of ginkgos by farmers. Millions of trees are also being raised on plantations in the United States, France, South Korea and Japan for the export of their leaves to Europe.

Temple gardens

The saviours of the ginkgo are the religious orders – Buddhists in China and Korea, and followers of Shinto in Japan – who cultivated them in early times. Today, the very finest examples of the ginkgo are to be found growing in temple gardens in these three countries. It is not clear exactly why ginkgos were adopted as temple trees, but their re-emergence as ornamentals was noted as far back as the eighth century.

The pinkish-yellow fruits that develop are small, plum-like and hang in pairs. They are, however, notorious for their unpleasant smell. Harvard ginkgo expert Peter Del Tredici was curious about why the fruits smelled so bad. However, once he learned that nocturnal hunters such as Chinese leopard cats and masked palm civets, attracted by the smell of rotting flesh, ate the fruits, he postulated that the seeds needed to pass through the gut of animals to aid germination. His experiments revealed that after passing through the gut, germination rates increased from 15–71 per cent. Ginkgos have existed for so long that it is interesting to speculate on the kind of primitive mammals or dinosaurs that might have eaten these fruit 150 million years ago.

Despite the toxic outer coating of the ginkgo fruit, the seeds inside have long been prized as a food. The whitish or silvery nuts are cracked open to reveal the kernel, which – after roasting – is eaten as a delicacy in the Far East.

Koreans collect the fruits for both food and medicine. Roasted ginkgo kernels are sold on the streets of large cities such as Seoul, while the fruits are used to make remedies for coughs, bladder complaints and asthma. In modern China, alongside their medicinal uses, the fruit are still served at wedding feasts as a symbol of fertility. Other uses include a detergent for washing clothes and a cosmetics ingredient.