TWENTY-FIVE

THE ASPHALT ROAD NOW ENDED, and we climbed a hill that was covered by tall trees. We were traveling to Afrin, to the border where people gathered to smuggle themselves through the fence separating Syria from Turkey. Turkish border guards, jandarma, would be patiently awaiting them, and when they caught the border-hoppers they allowed themselves the relief of shooting into the air or at the ground near their feet, or simply running after infiltrators who were slowed down by heavy bags.

Perhaps the infiltrator had just escaped his mandatory Syrian military service, like eighteen-year-old Saleem from Damascus—who had spent nearly a week in a transportation truck, hiding under a bed each time the driver sighted a government checkpoint. Saleem finally arrived in Raqqa, where his father paid the truck driver good money for his service. Saleem then sat next to me in a different vehicle all the way to Afrin. Perhaps, like Hamza al-Ojaili and his beautiful wife, Wafaa, a veteran high school teacher, they just wanted to visit their families in Turkey for Eid. Saleem and I carried Wafaa’s bags all through the smuggling route, jumping and climbing. Hamza and Wafaa must have packed every manner of foodstuff they had in their kitchens, figuring that their son in Şanlıurfa probably missed Syrian cuisine. Their bags were bursting, and our arms were aching under the weight.

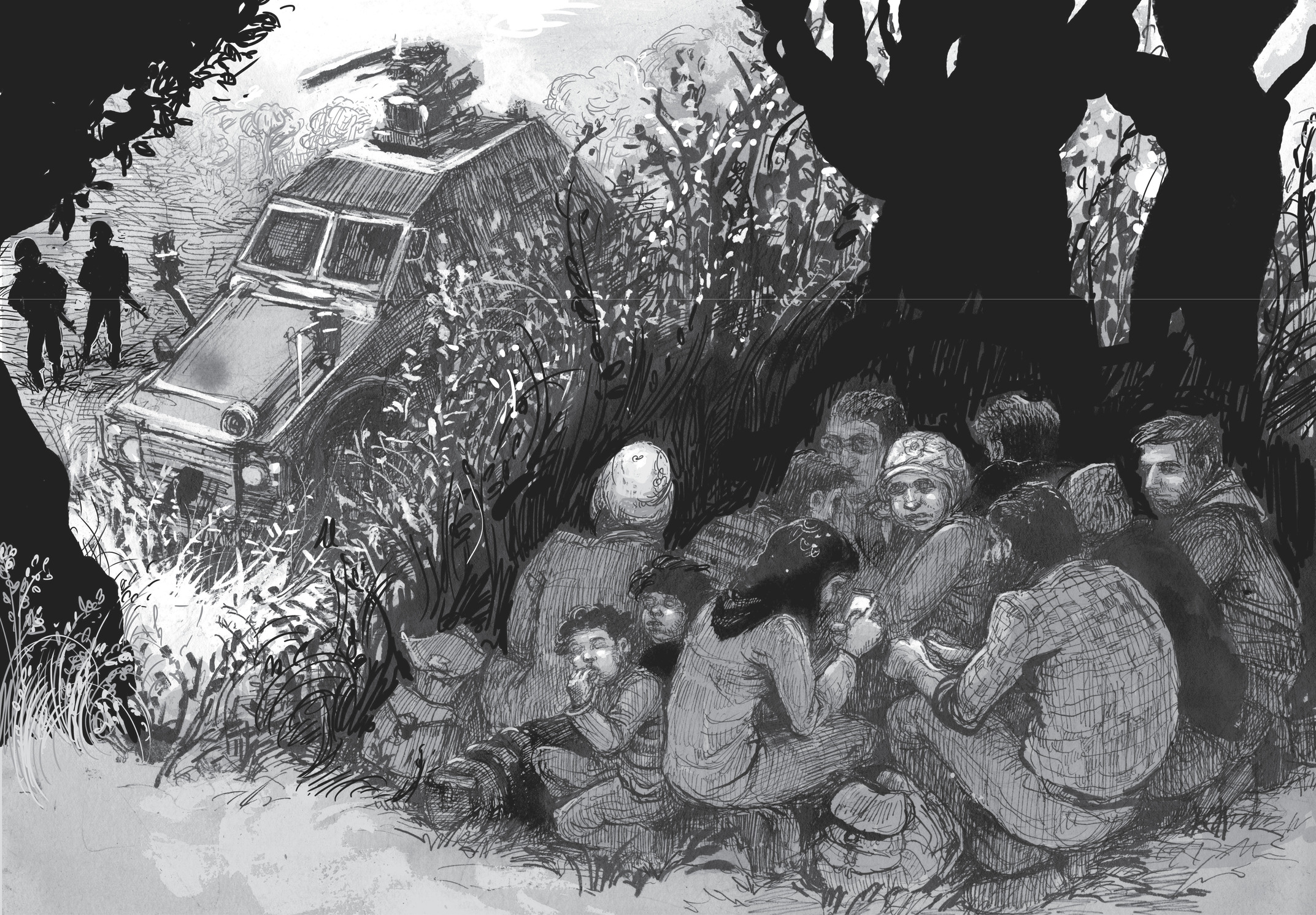

As we drew closer to the border, the trees disappeared, replaced by shoulder-high bushes; across the plains, the jandarma’s fatigues flickered into sight. We knelt with the crowd under the bushes. We spoke in low hisses. We were spotted anyway. So proudly, so confidently did those khaki uniforms approach, striding across the bosky hill. When our eyes met, they whooped in triumph. It was their moment to assert supremacy over us, desperate humans whom the Turkish government had named guests—lacking the regular status of refugees perhaps, but still welcome in the country—but whom they, the border guards, had been ordered to relentlessly chase, even shoot, to prevent from crossing into their country. The lively hunters flocked around their prey. Their insults fell upon anyone who attempted courtesy—especially the one among us who was serving as a tercüman—a translator. Compounding his bad luck, he was also a Kurd. The border guards slapped him each time he translated a sentence, and you, dear reader, needn’t wonder why. An old man, in his seventies perhaps, traveling alone, cried that he had fled his house in the Sukkari neighborhood of Aleppo after the barrel bombs fell. Almost fainting but still refusing to break his Ramadan fast, he said that he wished he had stayed home to die. A border guard slapped him across the face. A guard pushed a young lady so that she fell on her back. Luggage was searched, painfully preserved possessions thrown away. One jandarma roared words that sounded like prayers. He carried a little girl in his arms and kissed her playfully—right after insulting her father. Another guard’s eyes rested on an Iraqi Kurdish man’s watch. He asked to take it as “a gift.”

“It was a present from my wife,” the man said. The soldier laughed and gestured cryptically, but I didn’t get a chance to see the watch’s fate.

DEEP IN THE WEST, high on green cliffs embroidered with generous olive trees, in territory delineated by a dotted line on a map featuring the end of Syria, live Kurds. Behind their backs, their eternal enemies—the Turks—exist as armored vehicles, as camouflage-coated shapes who point guns from the cracks of their outposts. The jandarma who guard the border with the YPG-held canton of Afrin are less murderous if you are an Arab trying to cross, but it does them no harm to send inferior Syrians back to their homeland.

If you are a Kurd…well, the mere fact that you’re crossing next to me might cause me a problem, more humiliation to be exact, at the hands of the soldiers who guard this line. But I’ll forgive you. Because the farther we are from home, the more similar we become. The thing is: Once we cross this damn wire and the trench behind it—assuming we aren’t blown up by mines or shot in the head—we become Syrians, and barely anything else matters. Miraculously, one step back inside and we return to our roles as “Arabs” and “Kurds.”

In Raqqa, Kurds made up perhaps a third of my neighbors. Every March, Kurds threw a massive party on the outskirts of the city to celebrate Newroz. Newroz is the Persian New Year, but for Kurds it had a different meaning. According to the myth, thousands of years ago a blacksmith named Kaveh defeated the serpent-wielding, brain-eating Assyrian tyrant and then set the hillside aflame in celebration. The story speaks of Kurds’ centuries-long repression at the hands of non-Kurdish rulers. The Assad regime feared that these celebrations were calls for separatism, and every year security forces sent patrols to drag off and interrogate any Kurd who dared utter a nationalist slogan. My Kurdish neighbor, an elderly man from a village near Kobane, had a midsized truck he would use to pick up his people and drive to the space the government assigned to Newroz celebrations. There, Kurds gathered in their bright traditional costumes and danced encircling the fire. Then the police encircled them.

If most Kurds didn’t join in our revolution in 2011, it might have been because, in their minds, the Kurdish revolution had started in 2004. It kicked off at a soccer match in Qamishlo—the predominantly Kurdish town in Syria’s northeast that would later become the de facto capital of Rojava, the Syrian Kurdistan—where al-Futuwah, a team from Deir ez-Zor, was playing al-Jihad, the home team. Before the match, fans shouted at each other. Ugly chants. The words turned to punches, and soon clashes consumed the town. Security services fired live ammo at the Kurdish protesters, killing dozens—then arrested and tortured many more. When Kurds kept pouring into the streets in large numbers, the regime sent Division 17 of the army, which remained stationed in Raqqa ever since, to crack down on them. Kurds accused the army and the security services of taking the Arabs’ side. Despite this history, many Arabs couldn’t understand why in 2011 so many Kurds preferred to make their own Kurdish revolution rather than join the anti-Assad revolt. As a result, Arabs demonized Kurds as supporters of the very security forces who had spent decades brutalizing them—or as separatists only out for themselves.

What could unite Syrians, I wondered? Repression seemed the only practical answer. But weren’t these divisions vestiges of repression in the first place?

Who was the enemy, and who was the friend? Well, isn’t this a tangle of a question! The answer for both is everyone. The enemy could be the military service dodger or the traitor to the armed revolution—someone like me. He could be Tareq, who could reconcile himself to the fact that his enemies were other Syrians. He could be the pilot, who dropped bombs on humans of the same nationality as him. She could be that blogger. They could be the separatists, the nationalists, the Islamists, or simply the children behind the front line. The same confusion applies to the word friend. Syria’s real loss wasn’t the millions of displaced civilians, nor the hundreds of thousands of casualties. It was the practical side of identity, real or fake. That illusory identity, bounded by a line drawn on paper, was never really shared but instead was enforced by the de facto world system. Later, the more certain you were of your “real,” which is to say nonnational ethnic, religious, or tribal, identity, the more you reflexively clung to the war. And war is an ugly word.

I remember every time I was forced to leave my religious school during a holiday, wearing a gallabiyah and white skullcap. People stared at me, a scary and scared teenager, as if I were an alien, rudely assaulting their eyes with my presence, and, oh, I was ashamed. I knew, and hated, the way they identified me—I was a religious larva hatching inside its shell, a parasite in an already unproductive society. What Syria needed then, I thought, was economists and talented change-makers to improve our impoverished lives. What Syria needed then, I was taught, was more memorization of religious texts and sayings. Five years after I took the decision—my dearest—to leave this religiosity once and for all, there came a generation that attached ammo to those garments and masculinity to those beards. They hijacked not only the uprising but my life as well, and then they looked down on me, as if I was the one who was supposed to be ashamed. I had counted on the majority to defy such aggression, but instead they remained silent at best and complicit at worst. I watched my society lurch backwards with agony and despair. And I was furious at my people for being so politically ignorant that they couldn’t see what was deteriorating and at the outside world for denying me the choice of how I would be identified. And now here I was, on the border, leaving at last.

If the war gave me anything, it was a visceral knowledge of how empty humans can be, and how wretched. When you are a programmed machine with a gun, all that is left in you that is human is the feeling that you are invincible; when you are not, you know exactly how weak you are. I watched a young man held tight by those Turkish soldiers. One of the soldiers drew his hand across the young man’s throat, in the unmistakable gesture of a knife slit. “We’ll send you back to Daesh to have your heads chopped off,” he seemed to mean, and exactly so the tercüman translated.

“Why did I come?” I asked myself.

NOW, ALLOW ME TO tell you the story of Haj Mahmoud.

Haj Mahmoud was my family’s neighbor, who worked hard throughout his life. From Saudi Arabia to Jordan, he spent years striving for the good of his family. Exhausted and growing old, he took his reward for decades of toil: a rusty 1970s Mercedes truck, which he loaded with gravel for construction projects, charging three thousand Syrian pounds for each transport. He resembled the bulk of his generation, who exerted themselves for the family and the family alone. To me, the goal of having a family and then spending the rest of one’s life caring for them had begun to seem meaningless. But not to Haj Mahmoud, and not to the majority who were like him.

Years passed. War settled in to Raqqa, and so did foreign fighters. Haj Mahmoud wasn’t fond of the regime at all, but he hoped for peaceful days. When Raqqa fell to the rebels, he anticipated frightful consequences. He had already gone through troubled times in his pursuit of money. It was as the poet Ilyas Farhat described: “I head west, chasing after a livelihood while it is heading east…And I swear, had I headed east, that livelihood would have been heading west.”

But the war drums were beating, and Haj Mahmoud did his best to keep his sons deaf to their boom. The war defeated him. Its eyes fell on his youngest son, Hamid.

When Hamid joined ISIS, Haj Mahmoud knew that he could do nothing. One of the basic principles taught to young ISIS recruits is this: Jihad is an obligation. Parental consultation, not to say consent, is completely unnecessary. Despite this, he tried his best and went to visit the training camp to cleanse the brain of his youngest son of ISIS brainwash. When he returned, his wife, Maryam, was waiting.

“What happened? Did you find him? Where is he?” She fired her questions at once, but the old man didn’t move his lips. He entered the room and closed the door. He was weeping. “Back in the days before, he would never cry,” Maryam told me when she visited me later, “not even when his mother and father died.” Haj Mahmoud had realized the depths of his own helplessness—gutters of nullity that his years of work, of fatherhood, had never prepared him to imagine he might inhabit. With his rebellion, Hamid had torn his father’s heart apart, then devoured what was left of his energy.

You might think that this story is about ISIS. It is not.

Maryam wearily approached Haj Mahmoud and asked, almost voicelessly, “Did anything happen to Hamid?”

“He’s okay,” he answered firmly.

She sighed heavily, then silence overwhelmed them both.

A minute passed. Another sigh, this time from Haj Mahmoud. Burdened, he finally succumbed to the desire to share his puzzlement. Maybe it would console her. His confession delicately broke the silence. “I saw doctors, engineers, and other well-educated people. And those from other countries, who had left their homes and come all this way to fight for ISIS. I closed my mouth and returned. How can I convince him while he’s among those people?”

By that time, it was September 2015. ISIS was deep in war with the YPG, and the corpses of nine neighbors’ sons had arrived from Kobane. Countless others had been buried where they fell, some as far away as the Kurdish town’s outskirts. All that was known about some was that they had been ripped to pieces by coalition bombs.

One afternoon, a few days before the blood clot stopped his brain, Haj Mahmoud came to his wife, inhaling deeply. “I’m tired, Maryam,” he whispered, in a way that she could barely hear. He held his grandson’s hand. “The kid is tiring me,” he added. “Which one?” she asked knowingly. “This kid,” he replied, as if referring to the grandson. She understood that he meant Hamid. She kept silent, deep in her own sorrow.

Every time a new body arrived, Maryam was waiting for her son’s. Like Haj Mahmoud, she wished to die before that moment came. Each time, she wondered, unanswerably, about the purpose of this war against the Kurds.

The last time Maryam visited me, she hugged me as if I were her son, “even if it’s not permitted by Islam,” she said, smiling faintly. Haj Mahmoud had died and found peace. He left all the burden to her. Every once in a while, her eyes traced the edges of her husband’s grave. Tears do not bring back the dead. They are too salty. Not even flowers grow where they fall. “Hamid killed him,” Maryam told me. Her friend Um Nofal nodded at everything Maryam said. At last, she said everything that came into her mind: “Syrians have become soil.” At the time, it sounded to me like a meaningless sentence, until I figured it out later; she probably meant that we were already dead.

THE BORDER GUARDS TURNED the crowd back toward Syria. In the chaos, Saleem and I lost track of Hamza and Wafaa, but their bags were still with us. Twilight had just started to fall. Once it was dark, we had another chance to cross. We had to take it. There was no time to look for the others. War is harsh on the compassionate and the weak. I did one of the many terrible things I’ve done in my life.

I left them and their bags behind.