Written sources for the tumultuous events that were to follow are surprisingly few in number. A long account from the Mongol side appears in the Yuan Shi, the official history of the Yuan dynasty. This parallels in several important points a Japanese source called Hachiman Gudokun, a work concerned with the efficacy of prayers offered to Hachiman, the deified Emperor Ojin who was the kami of war. Hachiman Gudokun is believed to date from not long after the invasions as it was intended to be used as a lever to obtain reward from Kamakura. The earliest copy of the text to survive is dated 1483. As the prayers noted include individual ones uttered by samurai on the battlefield as well as one requesting the divine help that was to be provided in the form of the kamikaze, it is very valuable for its brief accounts of the military tactics used by both sides.

Hachiman Gudokun is complemented by the text and illustrations of the famous Moko Shurai Ekotoba (Mongol Invasion Scrolls), the painted scrolls with accompanying narrative commissioned by an ambitious samurai called Takezaki Suenaga who sought reward for his services. Taken together, the two documents enable us to reconstruct the nature of the fighting at both a macro and a micro level, yet these sources are almost all we have. There are no long narrative epics of the Mongol invasions comparable to Heike Monogatari for the Gempei War or Taiheiki for the wars of the 14th century. Nichiren Shonin Chu-gassan is concerned with the influence of the priest Nichiren and contains some useful information, and there are in addition shorter references in family histories concerned with certain ancestors’ exploits during the Mongol wars, and numerous official documents. Many of these latter sources, together with the text and captions of the Mongol Invasion Scrolls, are usefully presented in Thomas Conlan’s book In Little Need of Divine Intervention.

The Mongol invasions of Japan pitted against each other two types of warriors who differed considerably from each other in appearance, armament and tactical method. Both the samurai and the Mongol warriors traditionally prided themselves on their abilities as mounted archers, although the ways through which they approached the art of horseback archery were very different. Many centuries before the famous samurai sword was being lauded as the ‘soul of the samurai’, the Japanese warrior was being praised for his skills in kyuba no michi (the way of bow and horse), and some of the most glorious episodes in the accounts of the Mongol invasions tell of samurai killing Mongol commanders with arrows from horseback. It is a skill maintained to this day through the martial art of yabusame (horseback archery) although the amazing prowess demonstrated at festivals such as those in Nikko and Kamakura may be a little misleading. Yabusame is now practised by men wearing light hunting costume riding modern horses, while during the 13th century arrows were delivered by samurai wearing suits of armour and riding much smaller horses.

The samurai who fought against the Mongols in 1274 and 1281 were essentially mounted archers who preferred to seek out an honourable opponent to fight. The unfamiliar tactics of the Mongols required several changes to be made to Japanese warfare, although the individual samurai spirit still managed to assert itself successfully on many occasions.

The Mongols too fired arrows from galloping horses, but in a much looser ‘light cavalry’ style, although there also existed Mongol ‘heavy cavalry’ who were armoured and could deliver a devastating charge. However, the conditions pertaining to the Mongol invasions of Japan meant that both sides had to do a considerable amount of fighting on foot, either on dry land or from the deck of a boat, although organized infantry operations were confined to the Mongol side, where Chinese and Korean footsoldiers were controlled by drums and gongs that indicated the performance of simple tactical movements in which they had clearly been drilled. The short arrows delivered from within these ranks came in huge volleys, unlike the preferred Japanese method which was to deliver a single arrow against a chosen and, hopefully, worthy target whose death would earn the warrior considerable individual glory. The tactical formations adopted by the Japanese therefore consisted of a series of small warrior bands led by a prominent samurai with a handful of followers and the support of anonymous footsoldiers armed with naginata (curved-bladed polearms). This pattern was to be repeated in the raids the Japanese conducted against the Mongol ships in 1281, when similar small warrior bands united by kinship or long service were taken out in small boats and attacked the Mongols with bows and swords.

Archery also played a key religious role in the way a Japanese battle traditionally began. The first arrow loosed by either side at the start of a samurai battle would have been a signalling arrow shot high into the air over the enemy lines. Each signal arrow had a large, turnip-shaped perforated wooden head which whistled as it flew through the air. The sound was a call to the kami to draw their attention to the great deeds of bravery that were about to be performed by rival warriors. This was done when the Mongols landed at Hakata but provoked only raucous laughter among the ranks of the invaders. It was an omen of what was to follow, because supposedly the two armies would then clash in a series of small-group or individual combats between worthy opponents. Again by tradition, these worthy opponents sought out each other by issuing a verbal challenge that involved shouting one’s name as a war cry. Epic chronicles such as Heike Monogatari regularly exaggerate this process so that the challenging samurai is made to relate an account of his exploits and the fine pedigree of his family. The challenge would supposedly be answered from within the opposing army, thus providing a recognized mechanism whereby only worthy opponents would meet in combat. Leaving aside the obvious difficulties of being able to conduct verbal negotiations among the din of battle, there are in fact very few examples in the chronicles where very elaborate declarations are recorded. Instead a more likely scenario is that samurai, when entering a battle situation, shouted out their names as war cries in general, rather than specific challenges. But even if that had been the expected way to fight, surely in 1274 no samurai would have been so stupid as to think that the Mongols spoke Japanese. Instead the seeking of worthy opponents, when it did happen, consisted of targeting anyone mounted on horseback, wearing a fine suit of armour and with an accompanying standard-bearer. The clouds of Mongol arrows, some of which were poisoned, that were loosed in return from within the invading squads must have caused further problems, but once the fight developed into hand-to-hand combat there was no opportunity for such haphazard archery.

For centuries there was only literary evidence for the nature of the Mongols’ ‘secret weapons’ – the exploding bombs thrown by catapult against the Japanese defenders. They are now known to be identical to the Chinese zhen tian lei, which were of iron or ceramic material and were filled with gunpowder and shards. Paper-cased bombs were also used against Japan. These examples are among the bombs brought to the surface as a result of the underwater archaeological investigation off the coast of Takashima, and are on display in the museum on Takashima.

The most interesting weapons used by the Mongols during the Japanese invasions were the exploding bombs, which were the single most important innovation of the war. They provided the first examples of gunpowder explosions ever heard in Japan and caused considerable surprise to men and horses alike. For many years no one was exactly sure what these bombs were. Earlier scholars suggested cannon, and put them forwards as evidence that the Mongols used gunpowder as a propellant in the later 13th century. This was not the case, because the bombs were in fact delivered by catapult and the explosions heard were the missiles themselves breaking apart. Underwater archaeology over the past 30 years has added greatly to our knowledge of the Mongol invasions in general and the exploding bombs in particular, although physical evidence of the latter has taken years to acquire. Several have now been found, and they are now known to be identical to the weapons known to the Chinese as zhen tian lei (thunder crash bombs or, more literally ‘heaven shaking thunder’), that killed people by the shattering of their metal cases and destroyed objects by the force of the explosion that is implied by the dramatic name. Their invention is credited to the Jin dynasty, and their first recorded use in war dates from 1221. The fragments produced when the bombs exploded caused great personal injury, and one Southern Song officer was blinded in an explosion which wounded half a dozen other men. The Mongols had acquired the use of exploding bombs by the time of the beginning of the siege of Xiangyang in 1267, but they also suffered casualties from them, including a certain Mongol officer who led the attack up scaling ladders. A bomb fired from a trebuchet exploded beside him causing a serious wound in his left thigh.

Throughout samurai history the greatest proof of duty done was the presentation of the severed heads of one’s enemy to one’s commanding officer. In this section of the Mongol Invasion Scrolls, Takezaki Suenaga (on the viewer’s left) proudly displays two such trophies in front of the acting shugo of Suenaga’s native Higo province, Adachi Morimune. In front of them sits a scribe to record the achievement. (From a hand-coloured, woodblock-printed book based on the Mongol Invasion Scrolls)

When used during the Mongol invasion of 1274 their novelty produced a further level of terror among the Japanese. One account notes how these ‘mighty iron balls’ were flung, and ‘rolled down the hills like cartwheels, sounded like thunder, and looked like bolts of lightning’. Different types of bombs having a soft case made from successive layers of paper also appear to have been used during the Mongol invasions, a conclusion suggested by the Hachiman Gudokun reference to ‘paper bombs’ in addition to ‘iron bombs’.

Nevertheless, in spite of bombs, poisoned arrows and dense ranks of infantry, the accounts that exist of the actual fighting that took place on Tsushima, and afterwards on Iki Island and the mainland of Kyushu, show that the samurai were far from being stunned into inaction by the novelties of Mongol warfare. Language difficulties, of course, precluded the conventional name-shouting for any audience other than the samurai’s own comrades, but in terms of making a name for oneself that domestic audience was vital, and we will see how the presence of witnesses to brave deeds was absolutely central to the reward process. An additional proof of duty done was to return with the severed head of one’s opponent, and if the goal was simply to take the largest number of heads, the Mongol armies provided numerous targets for the mounted samurai archers. Head-collecting, however, was a tradition often misused throughout samurai history and the Mongol invasions are no exception. During the invasion of 1281 a certain Kikuchi Jiro went a little too far, and roamed among the Mongol dead, decapitating corpses and bringing back a large number of supposed trophies to add to his own tally.

This blade from a nagamaki (a polearm with a long slightly curved blade) was used in battle against the Mongols by the Japanese hero Kono (Kawano) Michiari. Kono then presented it to the Oyamazumi Shrine on the island of Omishima, where it is on display.

The samurai and the Mongols also provided a considerable contrast in terms of physical appearance. By the 13th century most samurai were wearing armour of a characteristic box-like design known as a yoroi on top of a fine robe and trousers. Yoroi armour was made from small scales tied together and lacquered, then combined into armour plates by binding them together with silk or leather cords. The result was a flexible defence whose efficiency lay in its ability to absorb the energy of a blow in the lacing sandwiched between the rows of scales before penetration could begin. Each scale was of iron or leather. A suit made entirely from iron was far too heavy to wear, so the iron scales were concentrated on the areas that needed most protection, and otherwise alternated with leather. The separate parts formed the classic samurai armour, which provided good protection for the body for a weight of about 30kg. In fact the main disadvantage of the yoroi was not its weight but its rigid and inflexible boxlike structure, which restricted the samurai’s movement when he was dismounted or using hand weapons from the saddle. If the samurai stayed as a ‘gun platform’ on his horse then the yoroi was ideal.

The body of the yoroi armour, the do, consisted of four sections. Two large shoulder plates, the sode, were also worn, which were fastened at the rear of the armour by a large ornamental bow called the agemaki. The agemaki allowed the arms free movement while keeping the body always covered. Two guards were attached to the shoulder straps to prevent the tying cords from being cut, and a sheet of ornamented leather was fastened across the front like a breastplate to stop the bowstring from catching on any projection. The kabuto (helmet) bowl was made from iron plates fastened together with large projecting conical rivets. A peak was riveted on to the front and covered with patterned leather. The neck was protected with a heavy five-piece neck guard called a shikoro, which hung from the bowl. The top four plates were folded back at the front to form the fukigayeshi, which stopped downward cuts aimed at the horizontal lacing of the shikoro. Normally an eboshi (cap) was worn under the helmet, but if the samurai’s hair was very long the tied-up queue of hair was allowed to pass through the hole in the centre of the helmet’s crown where the plates met. Some illustrations show samurai wearing a primitive face mask called a happuri, which covered the brow and cheeks only. No armour was worn on the right arm, to leave the arm free for drawing the bow, but a simple bag-like sleeve with sewn-on plates was worn on the left arm.

A samurai armed with a naginata and wearing yoroi armour – a typical appearance from the wars against the Mongols.

No samurai would ever be without a sword, and a sword forged by a celebrated master was one of the most prized gifts that a warrior could receive from an appreciative leader. Yet much of the lore surrounding Japanese swords is of a comparatively late origin. At the time of the first Mongol invasion the primary weapon of choice for the battlefield was still the bow. Matters were to change somewhat over the course of the two invasions, and during the raids by boats against the Mongol fleet in 1281 the samurai sword finally came into its own. By the time of the Mongol invasions the creation, design and function of the Japanese sword was reaching its point of perfection, and the opportunities for hand-to-hand combat rather than arrow exchange at a distance provided the perfect test. The long, curved and razor sharp blades cut deeply into the brigandine-like coats of the Mongol invaders, whose short swords were much inferior. This contrast was to be noted during the ‘little ships’ raids.

The samurai in this woodblock print is dressed in the costume and armour typical of the time of the Mongol invasions.

The design of the traditional Japanese bow which the samurai wielded was very similar to that used today in the martial art of kyudo. To limit the stress on the bow when drawn the weapon had to be long, and because of its use from horseback it was fired from one third of the way up its length. The bows were of deciduous wood backed with bamboo on the side furthest from the archer, lacquered to weatherproof it. The arrows were of bamboo. The nock was cut just above a node for strength, and three feathers fitted. Techniques of drawing the bow were based on those needed when the bow was fired from the back of a horse. In this traditional way the archer held the bow above his head to clear the horse, and then moved his hands apart as the bow was brought down, to end with the left arm straight and the right hand near the right ear.

The inside of an armoured coat of a Mongol warrior, showing overlapping sections of leather that provided a light protection. (Genko Shiryokan, Fukuoka)

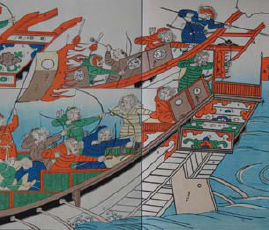

Mongol spearmen and archers are shown in action here from the stern sections of two Mongol ships. A standard-bearer hangs on bravely to his flag, while one unfortunate soldier clutches at a Japanese arrow protruding from his head. (From a hand-coloured, woodblock-printed book based on the Mongol Invasion Scrolls)

Descriptions of the physical appearance of Mongol warriors during the 13th century have much in common and stress their short and stocky appearance, accentuated by their heavy coats, boots and hats. By contrast, accounts of their prowess tend to differ only in the degree of exaggeration. For centuries the main sources of information were the descriptions left by visiting ambassadors, travellers and the like, who provided accounts that are often highly detailed but which were not written by military men. As a result it was often assumed that the typical Mongol warrior was very simply and lightly attired, perhaps wearing no more than a sheepskin coat and fur hat over his ordinary clothes. This may have been true for many light Mongol horse archers in the armies, but recent research, including some very valuable archaeological finds, has demonstrated that a Mongol army would have included a large number of heavy cavalrymen in addition to light cavalrymen. Heavy Mongol cavalrymen in armour appear on the Moko Shurai Ekotoba (Mongol Invasion Scrolls), the most important pictorial sources for the Mongol invasions of Japan. The basic costume of both types of warrior was essentially the normal daily wear of the Mongol. It consisted of a simple heavy coat fastened by a leather belt at the waist. The sword hung from this belt. A dagger was also carried, and perhaps an axe. In a pocket of the coat would be carried, wrapped in a cloth, some dried meat and dried curds, together with a stone for sharpening his arrowheads. His boots were stout and comfortable, being made from felt and leather. On his head he wore the characteristic hat of felt and fur.

A miniature suit of armour in the style that would have been worn by Mongol heavy cavalrymen.

The armour that the heavy horseman wore over his coat was made in the common Asiatic style of lamellar armour, whereby small scales of iron or leather were pierced with holes and sewn together with leather thongs to make a composite armour plate. A leather cuirass of this type weighed about 9kg. Alternatively a heavy coat could be reinforced using metal plates. The coat was worn under the suit of armour, and the same heavy leather boots were worn on the feet. The helmet, which was made from a number of larger iron pieces, was roughly in the shape of a rounded cone, and had the added protective feature of a neck guard of iron plates. The Mongol heavy cavalry rode horses that also enjoyed the protection of lamellar armour. Beneath their armour and coat the Mongol wore a silk shirt, the fibres of which acted as a cushion for a spent arrowhead that had been slowed by the armour but had nevertheless punctured the skin. As armies had discovered centuries before, an arrow does its worst harm when it is removed from the wound and its barbed head tears the flesh. The silk shirt was not punctured. Instead its fibres twisted around the arrowhead. It could then more easily be removed with safety.

A Mongol helmet; it takes the form of a conical iron bowl with a neck guard of reinforced cloth on leather studded with iron rivets.

Many chronicles suggest that Mongol archery was often a decisive factor in a battle. Their bows, which were much shorter than the Japanese ones, were composite reflex bows made from yak horn, sinew and bamboo glued together then bound until they set into a single piece. When the bow was strung it was stressed against the natural curve, giving a strong pull. It was loosed from the saddle with great accuracy. Each mounted archer had two or three bows, kept within protective bow cases when on the march. Quivers contained arrows with several different types of arrowhead, and poisoned arrows are known to have been used in 1274.

A round wooden shield provided personal protection. The shield would be most useful during individual combat, when a Mongol archer would have replaced his bow within its case and turned to his sword. The sword had a slight curve like a sabre. Axes and spears were alternative hand weapons, and rounded maces also appear in the written accounts. Mongol heavy cavalrymen also carried spears. The other field equipment of a Mongol warrior included a light axe, a file, a lasso, a coil of rope, an iron cooking pot, two leather bottles and a leather bag closed by a thong to keep clothes and equipment dry.

The Mongol Invasion Scrolls also show numerous footsoldiers, most of whom are Korean, arranged in formations with spears and shields. They wore long, heavy coats and stout, leather boots, with their helmets fastened tightly round their faces like veils. The shields are large and appear to be made from some sort of interwoven wood, probably bamboo. Japanese shields, used only by footsoldiers to create a barrier, were of solid wood.