Early in my paddling career, when I got into moving water that was at the frontier of my limited ability, my first impulse was to paddle harder, as if speed and power were the antidote to the absence of skill and control. It was the “ramming speed” phase of my evolution, which I count myself lucky to have survived, when paddling through rapids had more in common with driving bumper cars at the amusement park than with navigating current with any semblance of grace.

It happens that greater speed is called for about 10 percent of the time. The other 90 percent, more speed just makes bad things happen sooner and more emphatically.

Most of the time it pays to be going about the same speed as the river, or slower. Coasting along at the speed of the current, the canoe will glide over small standing waves without slapping and taking on water, and paddlers can “sideslip” past obstacles (see this page). When you’re going slower than the current, backpaddling gently, the challenges of the river unfold in slow motion and paddlers can control the action by “ferrying” (see this page–this page) across the current and picking the best course.

About the only time more speed is called for is when the canoe is going through large standing waves, or when paddlers identify a general line to follow from well above and can afford to simply paddle forward into position.

On trips, when the canoe is loaded down with gear and a capsize is inconvenient at best and life threatening at worst, whitewater is a challenge to take cautiously. Save the rodeo moves for outings with empty boats and a road nearby.

In moving water with moderate current and well-spaced obstacles, sideslip left and right of obstacles by coordinating draw strokes and pry strokes. The stern paddler needs to time strokes in synch with the bow person to get a smooth slide across the current and to avoid a rocking motion. When the bow person does a cross-bow draw, the stern paddler draws on the same side. When the bow paddler draws, the stern paddler pries on the opposite side. The result is a simple slide left or right. The bow paddler is the one calling the shots, since he or she is in the best position to see the next obstacle.

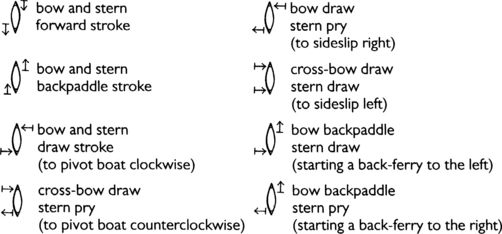

The key to the following canoe stroke scenario diagrams; bow generally faces in direction of current (top here).

Ferrying allows you to move sideways in current by paddling against the flow while angling the canoe to expose the hull to the force of the river, which pushes the boat left or right. It’s exactly the way a river ferry motors across current without losing ground. The stern person is responsible for maintaining the boat’s angle in the current (the slower the flow, the greater the angle you can get away with). Occasionally the angle will be too great and the river will push you broadside, and then the bow person can help regain the angle. Once the angle is achieved, the bow paddler strokes backward, against the current. The canoe will migrate across the river in the direction the stern is pointing. In really strong current, it’s sometimes best to pivot the canoe upstream, establish an angle, and then forward paddle, in which case the canoe will move across current in the direction the bow points. The forward ferry is a more powerful maneuver than the back ferry. Ferrying is an ideal way to run big water, since it slows the action and allows paddlers to pick their way down through ledges and tight obstacles.

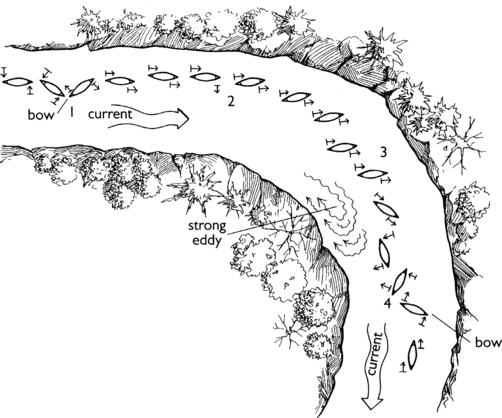

Series of three sideslip moves to avoid well-spaced rocks.

1. Bow draw—stern pry.

2. Cross-bow draw-stern draw.

3. Bow draw—stern pry.

Sideslipping works best in moderate current with well-spaced obstacles.

Canoeists back-ferry to skirt two ledges.

Bow backpaddles while stern adjusts the boat angle and backpaddles when possible. Bow helps adjust boat angle at the end of the ferry.

The back-ferry may be the most important technique in a paddler’s repertoire.

On sharp corners (those approaching a right angle) the strongest current flows forcefully into the bank on the outside of the bend, sometimes even undercutting that bank or cliff. The outsides of bends are almost never where paddlers want to be. The flow becomes more moderate toward the inside of the curve, and at the very inside the river is often eddying back on itself, sometimes powerfully. The trick is to ride that line between the eddy current and the downstream flow, avoiding both the outside bank and the clutches of the eddy. In very strong current that runs hard into a wall, an upstream or forward ferry may be the best way to avoid the wall and slip around the bend (see this page). In these cases paddlers may want to tuck right into the eddy to avoid the wall and then paddle out the bottom of the eddy. Generally speaking it’s prudent to approach bends on the inside of the curve until you can see around and assess the best strategy.

A healthy percentage of capsizes are, more accurately, “swamps.” They happen when a canoe goes crashing through a set of standing waves, taking on dollops of river with each one and filling to the gunwales. They happen pretty regularly during the ramming-speed phase of a canoeist’s life. In a loaded canoe, big waves are best appreciated from a distance, preferably as you sneak past in more moderate flow. Spray decks (see this page–this page) are good protection from swamping in waves. Smaller waves (under two feet) are easy to negotiate by slowing the boat’s speed to that of the river. A gentle backpaddle allows you to coast over waves at the river’s pace without taking on any water. If you feel the boat starting to wallow and turn sideways, you’ve slowed too much. If you can’t avoid large standing waves, it’s best to paddle forward through them, maintaining headway, while bracing for stability (see this page). Usually the bow paddler strokes forward while the stern person leans out on a brace to stabilize the canoe. Without a spray deck, it’s almost impossible not to ship some water in large waves.

Any expedition paddler worth his gorp is practiced in the art of sneaking down big water. Many rapids, especially on larger rivers, are famous for huge waves, rocks, and ledges in the main flow, obstacles most tripping paddlers want nothing to do with. More often than not, however, you can get past those pitfalls simply by hugging the shoreline and working carefully through the shallower, slower current (see this page). I’ve worked down miles of big water by leapfrogging along, stopping to scout, paddling ahead, stopping again, slipping blithely past all the big stuff, and avoiding the work of a portage.

Canoeists forward ferry to avoid sharp bend.

1. They turn canoe around well upstream.

2. They establish a ferry angle.

3. They forward paddle away from outside of bend, while avoiding the powerful eddy on the inside.

4. They turn the canoe back around.

Sharp corners on rivers always warrant a cautious approach.

Canoe going down V, then hitting large standing waves. I. Bow paddles forward while stern holds onto a high brace—draw stroke. 2. In smaller waves, paddlers gently backpaddle and coast through.

Slow to the river’s pace in moderate waves, but paddle forward and brace through really large ones.

Bouldery rapid with strong current and little room to maneuver.

1. Canoe sideslips to the left bank.

2. Canoeists set up a slight ferry angle to hug the shore.

3. They backpaddle gently along shoreline.

4. They sideslip slightly out to avoid a rock protruding from the left bank.

5. Canoeists regain ferry angle and back into the bottom of the eddy at the end of the rapid.

upstream stop to scout first

A good sneak has its own exhilaration, one made up of mastering technique.

On expeditions, I rarely do much in the way of eddy turns unless I’m playing around in a safe stretch of water or coming to shore into a big swirl. Eddy turns are more appropriate for whitewater days with empty boats. When turning abruptly into a powerful eddy the boat is inherently unstable. With a loaded boat I much prefer backing into eddies stern first (see the “sneaking” illustration). By doing so, you avoid the moment when you cross out of the main river current into the upstream flow of an eddy.

Still, eddy turns are fun, kind of like playing crack the whip on ice skates. You sweep around as if the bow rope has caught in a tree, the stern making that dizzying turn, and suddenly you’re stopped in the middle of the river, current rushing past, and looking upstream. So an eddy turn is a heady moment, when done right, and it’s worth practicing for the times you really need one.

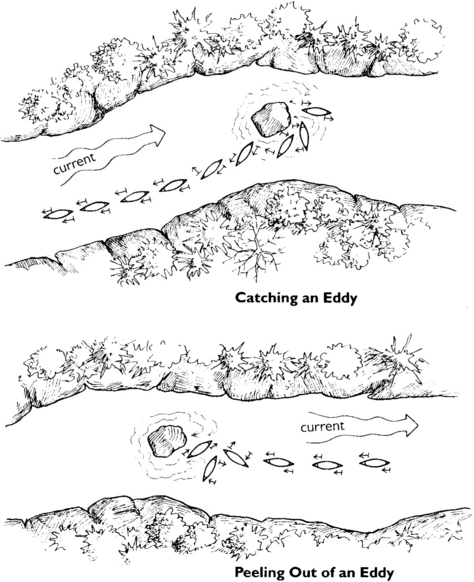

Eddies are the places in river current where the flow circles back upstream, sometimes with almost as much force as the main current. Usually eddies occur behind boulders or on the insides of sharp corners. Here’s how to catch one.

Identify the target from as far upstream as possible, and start angling the bow slightly toward the upstream end of the swirl (just past the boulder in the illustration on this page). As you come closer, broaden the angle of the canoe and paddle forward to have some momentum as the boat enters the eddy. At the top of the eddy, the bow paddler reaches into the swirl (with a cross-bow draw in the illustration) while the stern paddler helps pivot the stern (using a pry in the illustration). As the canoe enters the eddy, lean into the turn. This ensures that you’ll be leaning away from the upstream eddy current as the boat gets captured. (Always lean away from the force of current on a turn.) In the illustration, the bow paddler hangs on to the cross-bow draw, making it a high brace as well as a draw, while the stern paddler finishes off the pry with a low brace for stability. If you’ve done it right, you won’t even need to paddle forward to the top of the eddy. Usually it takes a forward stroke or two to finish off the move.

Coming out of the eddy is called “peeling out.” In strong river current, nose the bow back into the main flow at a narrow angle (too wide and you’ll be broadside and vulnerable). Again, the bow paddler crossbow draws and braces while the stern paddler pries. Both paddlers lean into the turn, or downstream to the main current.

Eddy turns are an essential skill to master, though they’re also inherently unstable.