Kamilikuak Lake, Northwest Territories: an out-of-the-way place in an out-of-the-way quadrant of the globe, where we have been windbound for a day and a half. Our canoes lie like colorful beached whales at the margin between rock shore and tundra moss. A dazzling chunk of shorefast ice is visible on a distant island, even at the end of July. Waves have been crashing in, hour after hour, a maddening percussion section played by the wind.

We go to the tents vowing to get up very early to check conditions. No one has a watch, and the sun is above the horizon twenty hours a day, so early is a relative thing.

A short night later the wind has died, the sun is astride the horizon again, and we are poised for escape. Silence is so complete it’s eerie. Our strokes puncture the stillness. We’ve lost the wind, but now fog lies against the frigid water in a quilt so thick we can only dimly make out the shoreline a few canoe lengths away. Relatively warm air condensing against cold water produces the ground-hugging cloud conditions, and we’re paddling through the pea soup variety.

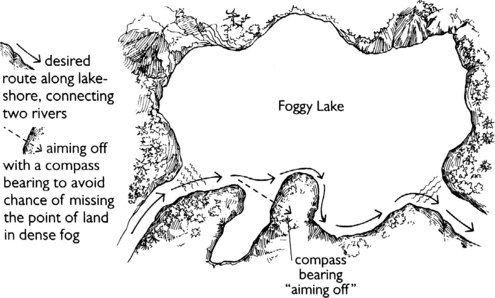

Around a point we have one of those “one mile across or six miles around” decisions to make. Through the fog, a mile away, lies the far side of a deep bay. To cut across saves us two hours of travel time. It’s calm, but we might as well be blindfolded. If we wander off course, we could paddle blithely into the middle of this big, cold lake.

We succumb to temptation and huddle with map and compass. Declination is a major correction. If we add when we should subtract, we’ll be wrong by thirty-five degrees. When we’re confident of the bearing (see this page–this page), we lay the compass at the feet of one bow paddler, get the arrows lined up, and strike off. The shore disappears in twenty strokes. We’re encased in a gauzy bubble. It’s the paddler’s version of vertigo, as if we’re balanced at the edge of the world.

We say nothing. Two boats slapping through small waves on a subarctic morning, blind as bats. The bow paddler points left or right when we slip off course. The canoes stay close. Everything is contained in this muffled, embracing, disorienting room. The crossing seems to go on for a long time, long enough that our minds start to play tricks and we doubt the flickering compass needle.

When land finally comes looming up out of the mist, we laugh out loud, babble with relief. Tension escapes like a breath held too long. But in another mile the fog has burned off and the wind starts to build again. Before lunch we’re surfing down wavefronts and have to make for land.

Another bit of cobble beach, another patch of tundra. We unpack only enough to boil up some coffee and soup, find books and journals, and pull out wind jackets. To while away time we take naps with our heads pillowed on life jackets, make short exploratory jaunts inland, eat snacks, talk.

It isn’t until after dinner that the wind dies again. It takes five minutes to pack and get on the water. Then we paddle for miles in the lambent light to a camp at the beginning of a short portage that will take us into the next large lake.

Take a bearing on a crossing to ensure landfall, even if it adds a little distance.

At first light the wind is gusty and cold. The portage has no trail, simply a marshy slog between lakes. Wind torques the canoes like weather vanes, grinds them against our neck vertebrae. We skitter across, stumbling over hummocks. On the far side the next lake is lathered like meringue. We hunker down in a hollow, wearing gloves and wool hats, and play euchre using a flat, lichen-encrusted rock for a table. The wind doesn’t quit until evening. We unbend, settle into boats, and paddle a dozen miles through a twilight that lingers half the night.

Where we stop there are tent rings left from an old Inuit summer camp. We lie on the same lumpy ground as they did. Our dreams hum with air tugging across the barren miles, but by morning it’s quiet as a cave, sun washed.

So it goes, day after day.

Weather is a compelling factor on any outdoor journey. In paddling boats across open water, weather is arguably the only significant factor. In thousands of paddling miles it has invariably been the stretches of open water that have proved my greatest obstacles and have served up the most vivid moments of danger. Moving water has its own set of challenges, some of them daunting enough, but when things go awry on a big watery expanse, it opens up the pores of fear like nothing else.

Wind is the breathing of the earth, and the bane of paddlers. It is caused by the interplay of cold and warm temperatures. On a global scale, for example, warm air rising at the equator produces a vacuum that pulls in cooler air from the north and south to create prevailing winds. On a local level the differences in heat between land and water, peaks and valleys, forest and rock produce smaller wind patterns. Onshore and offshore breezes. Upslope and downslope winds. Chinooks. All are the result of air flowing from cold to warm.

Large bodies of water are often significantly colder than the surrounding land, especially during the heat of the day. They are also flat, exposed topographic plains where winds gather over unimpeded miles, building waves as they come. Although there is no strict formula for safe travel in windy conditions, some guidelines are worth considering.

Islands and points offer cover from wind and often allow for travel on gusty days.

Angle the canoe into the wind and paddle with moderate strength against it. The net effect will be to move the boat sideways along the shore at a safer angle to the waves and with less need to correct course constantly.

Angling a canoe into a wind to move sideways down a shore.

Take advantage of the calm times of day—most likely early in the morning and again in the evening. Make miles early and then enjoy lazy afternoons in camp.

Take advantage of the calm times of day—most likely early in the morning and again in the evening. Make miles early and then enjoy lazy afternoons in camp.

Plan trips to capitalize on the least windy blocks of summer weather. In the Canadian subarctic, and on long trips on Lake Superior, July has invariably been the quietest month, while spring and fall trips are almost always plagued with wind.

Plan trips to capitalize on the least windy blocks of summer weather. In the Canadian subarctic, and on long trips on Lake Superior, July has invariably been the quietest month, while spring and fall trips are almost always plagued with wind.

Given the choice, pick a convoluted shoreline dotted with islands and points over a straight, exposed coast. You can often use topographic windbreaks to your advantage and make headway when you’d be pinned down along an unprotected shore.

Given the choice, pick a convoluted shoreline dotted with islands and points over a straight, exposed coast. You can often use topographic windbreaks to your advantage and make headway when you’d be pinned down along an unprotected shore.

If possible, situate camps in sheltered bays or behind a point of land. Sometimes just getting off the beach with waves breaking in is the trickiest move of the day.

If possible, situate camps in sheltered bays or behind a point of land. Sometimes just getting off the beach with waves breaking in is the trickiest move of the day.

Stick close to land in breezy conditions. The waves are always bigger once you get out in the open, and a few extra miles won’t kill you, whereas a capsize very well might.

Stick close to land in breezy conditions. The waves are always bigger once you get out in the open, and a few extra miles won’t kill you, whereas a capsize very well might.

When paddling in waves, play around to find the best angle for your bow. Many experts suggest “quartering” waves, but that depends on the shape and size of your hull and the load you’re carrying. Hitting waves straight on can be as safe as angling into them and avoids the risk of broaching sideways.

When paddling in waves, play around to find the best angle for your bow. Many experts suggest “quartering” waves, but that depends on the shape and size of your hull and the load you’re carrying. Hitting waves straight on can be as safe as angling into them and avoids the risk of broaching sideways.

Shift your load toward the stern to ride bow light and minimize the tendency to ship water.

Shift your load toward the stern to ride bow light and minimize the tendency to ship water.

In the case of a side or quartering wind, you can sometimes angle a canoe crabwise and ferry, using wind against the boat hull to push you in a desired direction, the same way you’d use current on a ferry maneuver on moving water.

In the case of a side or quartering wind, you can sometimes angle a canoe crabwise and ferry, using wind against the boat hull to push you in a desired direction, the same way you’d use current on a ferry maneuver on moving water.

It’s best to keep boats moving in choppy water. Momentum is a stabilizing influence, and paddles in the water have some of the effect of outriggers. As soon as you stop, the boat will start to wallow.

It’s best to keep boats moving in choppy water. Momentum is a stabilizing influence, and paddles in the water have some of the effect of outriggers. As soon as you stop, the boat will start to wallow.

In rough weather the temptation is to cling right against shore. In some cases breaking surf or waves rebounding off of a coastline can create difficult wave patterns. Experiment to find the best compromise between exposure and tricky water.

In rough weather the temptation is to cling right against shore. In some cases breaking surf or waves rebounding off of a coastline can create difficult wave patterns. Experiment to find the best compromise between exposure and tricky water.

Just as in whitewater, paddlers should kneel to lower the center of gravity.

Just as in whitewater, paddlers should kneel to lower the center of gravity.

Fabric decks, or spray covers, add a tremendous margin of safety (see this page–this page). Waves won’t swamp you in a decked boat, and if you get ambushed by a sudden blow, you’ll be much more capable of reaching shore without mishap.

Fabric decks, or spray covers, add a tremendous margin of safety (see this page–this page). Waves won’t swamp you in a decked boat, and if you get ambushed by a sudden blow, you’ll be much more capable of reaching shore without mishap.

Finally, any trip with lots of open water on the itinerary should be planned with extra time for windbound delays. An average of twenty to thirty miles a day might be feasible on moving water, but on big lakes I figure on ten to fifteen miles a day. It won’t always come that hard, but there have been trips where I’ve been windbound five days straight and had to struggle to manage a ten-mile average. Bring cards, miniature Scrabble, books, and other diversions to fill those enforced layovers.

Finally, any trip with lots of open water on the itinerary should be planned with extra time for windbound delays. An average of twenty to thirty miles a day might be feasible on moving water, but on big lakes I figure on ten to fifteen miles a day. It won’t always come that hard, but there have been trips where I’ve been windbound five days straight and had to struggle to manage a ten-mile average. Bring cards, miniature Scrabble, books, and other diversions to fill those enforced layovers.

If thunderheads are building around you and the air grows gusty and turbulent, it’s not a good time to strike off into the open. When a storm cell pounces, it can hit in seconds and pummel you with the force of a mini-hurricane. In regions that are serviced by twenty-four-hour weather reports, it can be worth packing a weather cube radio, but don’t treat the predictions as gospel. There’s nothing as accurate or immediate as your own commonsense reading of conditions.

Stay close to land in this kind of weather, or find a sheltered place to wait it out. Unfortunately, land can sometimes be as dangerous as water if trees and branches start to break off. The most protected spot I’ve ever waited out a fierce squall was in a shallow bed of marsh grass along shore. The vegetation damped down the waves, and I was clear of falling debris. I cowered under the onslaught in my raingear, feeling damn puny but relatively safe.

If you are caught in the open, hang on for the ride and summon all your reserves. The only good news is that the episode probably won’t last more than twenty minutes. The bad news is that twenty minutes will be an eternity.

Face bow into the wind and paddle just enough to maintain your position. Lower your profile as much as possible and be ready with a high or low brace to counteract sudden gusts or breaking waves.

As we discovered on Kamilikuak Lake, cold water and relatively warm air often conspire to produce a smothering blanket of fog. On large, cold lakes fogs are common, and they can be as disorienting as a howling blizzard in Nebraska. We’ve all heard of farmers who perished between the barn and the house in a snowstorm. Exactly the same fate can befall paddlers.

Early morning is the most common time to encounter fogs. They’ll usually burn off before noon, but any time a front moves in to change air temperature, fog can quickly develop. You can generally keep paddling as long as you navigate cautiously and keep land in sight.

The most foolproof preparation for fog is to have a compass always handy and to know how to orient it off a topographic map (see this page–this page). Once you have your bearing set, stick with it. A global positioning system would help in fog too, but a compass is a lot cheaper and more satisfying to master.

Paddling an exposed stretch of water when a lightning storm comes up is like being the high point in a flat grassland, only more so. Getting to shore is the most prudent course of action. Once on land, pitch a shelter away from summits of rock and clear of the tallest trees.

The theory that aluminum canoes are somehow more dangerous in a lightning storm is the stuff of myth. If you get zapped, you’re fried, no matter whether the boat hull is Royalex, wood, or Kevlar.

If you must keep paddling despite the threat of lightning, the safest corridor is right against shore. There’s a “shadow zone” of protection that generally extends at about a forty-five-degree angle from the top of the bank or forest out over the water. It isn’t guaranteed protection, but it’s safer than out in the open.

On oceans and estuary waters, tides are an important factor to reckon with. Some places are noted for huge tidal swings of thirty or forty feet, enough to dramatically change the character of river rapids dozens of miles upstream. Other coasts are so flat that even a minor tidal shift can send the water miles offshore. Much of the Hudson Bay coastline, for example, is prone to significant tidal effects.

Canoeists stranded by low tide in Hudson Bay, near Churchill, Manitoba.

It pays to have a tidal chart for these areas and to adjust your daily regimen accordingly. It sometimes makes sense to paddle only at high tide. If you go far out with a low tide and the weather changes, you might be in big trouble when the water comes back in.

Tides can also set up strong currents through tight channels. The Inland Passage along the western coast of Canada and Alaska is full of necks and channels where if the tide is shoving you back you might as well give up. By the same token, intelligent use of tides can make paddling like riding an escalator.

In tidal zones, pitch camp and stow boats well above the high tide and storm line, which will be marked by wave wash and lines of debris. Tie boats to rocks or vegetation for good measure. Nothing induces that empty feeling in the pit of your stomach like waking up one morning to find your boat has floated off.

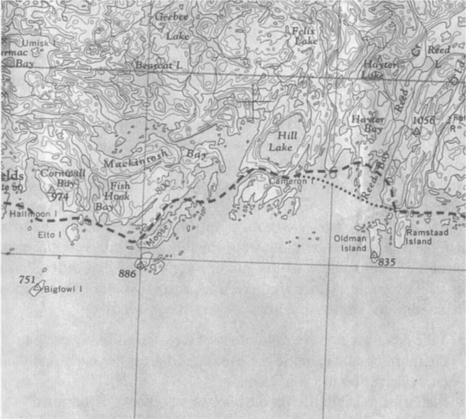

Extended crossings on lake and coastal trips are an inevitable temptation, and arguably the greatest paddling danger bar none. Time and again on these journeys the topography will tease you with shortcuts across bays and inlets. The temptation is tremendous, especially when the distance saved is significant.

Safe route adds only 2 to 3 miles, roughly an hour of paddling. Crossing the first, broad bay is particularly questionable.

Don’t assume distances are necessarily much longer along shore. Measure first to judge whether a crossing is really worth it.

Any crossing, even a mile or less, is potentially dangerous and deserves careful assessment. The shortcuts are often not as efficient as they first appear. Measure the actual map distances of a crossing against sticking near shore to see if the risk is worth it. If it seems to be but the wind is up, opt for the more rigorous, but safer, trip along shore. Even if the waves don’t seem bad near land, they are invariably larger and more dangerous out in the open.

Maximize the use of calm early morning and evening hours for larger crossings. I’ve made many a successful dash at first light that wouldn’t have been feasible two hours later.

In the Far North, and at the edges of summer, paddlers may encounter ice on large lakes. Before traveling to ice-prone country:

Research conditions by studying weather and climate charts to pinpoint the most ice-free windows for travel. July and August are usually safe months even at high latitudes, but don’t make rash assumptions. Stories of expeditions stymied by ice in any month of the year are common above sixty degrees north.

Research conditions by studying weather and climate charts to pinpoint the most ice-free windows for travel. July and August are usually safe months even at high latitudes, but don’t make rash assumptions. Stories of expeditions stymied by ice in any month of the year are common above sixty degrees north.

Contact guides, outfitters, aviation companies, and the like to find out about local conditions for a given year.

Contact guides, outfitters, aviation companies, and the like to find out about local conditions for a given year.

Look at maps to search out alternative routes around larger lakes, in case you encounter ice there.

Look at maps to search out alternative routes around larger lakes, in case you encounter ice there.

If, despite pretrip planning, you find yourself blocked by ice:

Wait a day or two to see if a change in wind direction will drive the ice pack away, at least temporarily.

Wait a day or two to see if a change in wind direction will drive the ice pack away, at least temporarily.

Remember that travel around an icy lake is usually best along the shore, because the rocks and land will hold heat and melt the ice margins.

Remember that travel around an icy lake is usually best along the shore, because the rocks and land will hold heat and melt the ice margins.

Sometimes paddlers have to haul boats across the obstruction, if the ice is firm enough to bear weight, or skate boats along with one foot inside the hull and the other pushing off the ice.

Sometimes paddlers have to haul boats across the obstruction, if the ice is firm enough to bear weight, or skate boats along with one foot inside the hull and the other pushing off the ice.

Confronted by impassable ice, pore over those maps to see if a portage over a neck of land, or into a parallel waterway, might bypass the icebound area.

Confronted by impassable ice, pore over those maps to see if a portage over a neck of land, or into a parallel waterway, might bypass the icebound area.

Keep in mind that the horizon from inside a boat is only two or three miles long. What appears like a heart-rending world of frozen pack may actually be pretty localized.

Keep in mind that the horizon from inside a boat is only two or three miles long. What appears like a heart-rending world of frozen pack may actually be pretty localized.

As a last resort, include a radio or emergency beacon in your outfit in case the ice is so bad you can’t complete the trip.

As a last resort, include a radio or emergency beacon in your outfit in case the ice is so bad you can’t complete the trip.

If you’ve seen the movie Titanic, you’ve been vividly reminded of just how lethal cold water is. That scene with hundreds of lifeless bodies bobbing around in the North Atlantic was literally chilling. Paddlers often dwell on the more exhilarating dangers posed by raging whitewater, but simple cold water is an equal, if not greater, threat.

HYPOTHERMIA SYMPTOMS AND TREATMENT

Mild to Moderate Hypothermia

(core temperature between 90° and 97°F)

Symptoms

• Awkward motor control (lighting a match, zipping zippers)

• Shivering

• Minor mental confusion

• Severe shivering

• More severe confusion, incoordination

Backcountry Treatment

• Adjust clothing layers (wind or rain gear, fleece)

• Eat some quick-energy food

• Exercise harder to produce heat

• Drink plenty of fluids

• Stop to build fire, boil water for hot drinks, change clothing, find shelter

Severe Hypothermia

(core temperature drops below 90°F)

Symptoms

• Mental status severely limited, loss of consciousness

• Shivering stops

• Pulse and blood pressure decreases

Backcountry Treatment

• Apply external sources of heat

• Get out of wet clothes

• Get in sleeping bags together to warm

• Rewarm slowly, then provide warm food and shelter, monitor for at least one day following

• Evacuate if possible

Even southern waters are colder than you’d expect. Unless the water is body temperature, lengthy immersion will inevitably sap heat from the body core, leading to hypothermia. Cold northern waters can be deadly in half an hour or less.

Practice self-rescue and group rescue techniques to avoid long immersions. If you can’t rescue yourself and have to wait for help, haul your body as far out of the water as possible on the hull of your boat and kick in toward the nearest landfall.

If a companion boat goes over, concentrate on rescuing people before gear, even if it means throwing some of your own outfit overboard. Canoe over canoe rescues seem neat on a calm pond but are often impractical, if not impossible, in big waves. Tie off packs and loose gear to bow and stern lines if necessary, but save people first and worry about gear later. The likelihood is that gear will eventually be driven up on shore.

Make sure everyone on a trip knows the basics for treating hypothermia. The most important thing to remember is that victims of hypothermia are not able to generate their own heat. External sources of warmth are critical. Far and away the best heat source is another warm body inside a sleeping bag. Other options include warm drinks (without caffeine) and food, fire, and warm sun. Keep close watch on victims of hypothermia for several days, since relapses can occur even after people appear fully recovered.

Well. By now you’re spooked enough that you won’t even venture out on the neighborhood pond. What I’ve neglected in all this fear-and-loathing diatribe is that open water travel is very rewarding, full of tranquil moments of beauty and exhilarating challenges. Prepare well, use good judgment, stay patient, and the benefits of paddling toward open horizons will overwhelm the risks.