GEORGE STEINMETZ

George Steinmetz is an exploration and science photographer who specializes in aerial photography. He is a frequent contributor to National Geographic and the New York Times. His latest work focuses on new developments in food science and technology and the issues associated with large-scale industrial food production.

Ounianga Sérir, a group of lakes in the Sahara Desert in northern Chad, is in the process of being cut into pieces by fingers of sand that blow through breaks in the surrounding cliffs. The heat and strong winds cause a high rate of evaporation that has caused the potable groundwater to become saltier than seawater and devoid of fish.

While I was on assignment for National Geographic magazine a few years ago, I got arrested for flying my paraglider over a cattle feedlot in Kansas, USA.

The arrest came as a bit of a shock to me. After taking photos around the world for the past forty years, I had run into my fair share of roadblocks: I was detained in Iran three times for spying while flying over the desert and in Yemen I was put under house arrest after taking photos of an archaeological site. But I found it really strange to be booked and put in jail in my own country for photographing agriculture. I was just flying over a rural area looking at patterns of cows and fences. What were they trying to hide? Then it dawned on me that there are parts of our food supply that the people who make it don’t want us to see. As a reporter you learn that when there is something that people really don’t want to talk about, you are getting close to a good story.

As a photojournalist, I have always been drawn to stories that are under-reported and difficult to tell. If someone tells me that I can’t do something, it only makes it more attractive. With pictures I try to show people things that they have never seen before. My goal has never been to tell others what to think or do, but to help people understand our world a little better through the photos I take.

Terraced crops climb the slopes of every mountain in northern Rwanda which is mainland Africa’s most densely populated nation. Nearly every speck of arable land is taken, so people are encroaching into protected forests. Land scarcity was a contributing factor to the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

I became interested in taking pictures somewhat by accident. I was finishing my third year at Stanford University, California, USA with a Geophysics major, but had no idea what I wanted to do for a living. So I decided to take a year off and go on a long hitch-hiking trip across Africa. I thought I would find wildlife and exotic tribes like I had seen in the pages of National Geographic, so I bought a camera from my brother and a lot of film. I soon found that taking pictures pushed me to meet strangers and put myself into unusual situations, whether it was the top of a water tower, or the inside of a hut with a medicine man. I liked the process. I also liked the pictures that I got; they told stories rather than being just pleasing to the eye.

Most of my rides in Africa were on the tops of trucks rolling down dirt roads. I sat on sacks of cargo, sharing kola nuts and learning French and Swahili from local traders and market women. Sitting up on top, I had this fantasy about what it would be like if I could fly over the African plains like a bird. I thought that if I could see it from above, I could decode the landscape. I could start to understand the geographic relationships and tell the story of a place. A lot of people don’t really think of landscapes as telling a story, but after studying geology and becoming interested in ecological relationships, I wanted to understand the forces that shape the land and make it the way it is. I wanted to take pictures that explained that.

Wheat crops on the Loess Plateau in central China. The fine, silty soil was deposited here by desert winds over thousands of years and the silt has been carved into terraces for agriculture. The wheat is mostly harvested by hand using a gasoline-powered disk saw mounted on a stick and the wheat stalks are then tied in bundles to dry before being threshed at home for family consumption. Farming on terraces like this is labour intensive and farmers are finding crops harder to maintain as their children migrate to the cities for higher paying jobs.

After returning to California, USA and refining my craft, I started getting work for magazines, eventually even top publications like National Geographic and the New York Times magazine. But that experience as a hitch-hiker stayed with me, especially the fantasy of flying over the vast tapestry of Africa, so I talked National Geographic into doing a big story on the Central Sahara. There were no planes or helicopters to hire in Niger or Chad, so I had to find another way and I learned how to fly a motorized paraglider, the lightest and slowest aircraft in the world. The motors are not so reliable, but in the desert I could make a running take-off or landing almost anywhere. In flight with a motor on my back, it was like a flying lawn chair, with unrestricted views one hundred and eighty degrees in horizontal and vertical dimensions. It was most interesting flying low and slow, from one hundred to five hundred feet [thirty to one hundred and fifty metres] above ground. That’s a height where you can see the world in three dimensions, but with a view of the dunes going all the way to the horizon. Nobody had been able to photograph such remote places that way before and I fell in love with these strangely surreal landscapes. After two trips in the Sahara, I decided to try the Atacama in Chile and Peru and then the Gobi in China and another and another. It took me fifteen years, but I eventually flew over every extreme desert in the world, in twenty-seven countries, plus Antarctica.

‘Over the years, my work has turned me into an accidental environmentalist. I never set out to be an advocate for our planet, but I think that if people know more about an issue, they can make choices that will lead to solutions. Our individual choices add up.’

An aerial view of Brookover Ranch Feedyard which is situated just across the Arkansas River from Garden City, Kansas, USA. The adjacent centre-pivot crop circles provide feed to fatten the cattle.

Approximately 3,300 hutches provide shelter for newborn calves at a large dairy operation in Wisconsin, USA.

‘I realized there are big parts of the food chain that consumers don’t really understand. I think if people understood more about what they were eating and how it’s made, they would make different choices.’

As I was finishing up my desert project, an editor at National Geographic asked me if I would be interested in using my paraglider to photograph farming for a series on meeting the future food demands of humanity. I realized that it could be most interesting to look at mega-farming, not the red barn with a cow under a tree. I knew from my time in Africa that from the air you need big herds to get interesting pictures of wildlife and for farming I would need to focus on mega-farms, with row upon row of repeating patterns. My editor liked the idea and sent me to Kansas.

The experience of getting arrested for flying over the feedlot made me want to look closely at other parts of our food supply and like the deserts, one kind of food has led to another. Most people want to see beautiful photos of the food they eat. If you look at food magazines, they like to show the latest restaurants with beautiful food and the cool chef with the tattoos. They don’t want to deal with the reality of where that food comes from.

But as I started documenting food production, I realized there are big parts of the food chain that consumers don’t really understand. I think if people understood more about what they were eating and how it’s made, they would make different choices. I don’t want to tell people what to do, but I hope my work can help them make more informed and responsible decisions.

A turkey farm in Clayton County, Iowa, USA, which houses 18,000 turkeys at different stages of growth. The birds are fed a mixture of corn and soybean meal, supplemented with minerals. They require just over two pounds [one kilogram] of feed per every pound of weight gained and grow from a chick to a twenty-four pound [ten kilogram] sell-weight bird in eighteen weeks.

The ancient oasis town of Chinguetti in northern Mauritania was founded in 1262 at a crossroads for caravans carrying salt. It has long had a struggle with being buried by mobile sand dunes.

‘We are entering an era of limited resources. We’re getting to the point where we’re running out of fish in the sea and virgin terrain – we’re consuming resources faster than they are replenished – and we have to start thinking about how we can reduce our impact on the world.’

For example, most consumers have no idea about the link between what they eat and the destruction of the Amazon rainforest. A few years ago, I chartered a small plane in the Amazon basin during the peak of the dry season, which is also the peak fire season that leads to deforestation. If you look at a timelapse of satellite data of the Amazon from the past few decades, you can see that it’s dissolving: It looks like it’s been nibbled to death by termites. I saw the same thing in other tropical forests in Indonesia and Malaysia. These areas are the greatest repositories of biodiversity on the planet, with an uncountable number of distinct life forms. We are chewing up these forests for hardwoods, paper pulp, palm oil, soybeans and cattle ranches. People in the developed world aren’t aware of their complicity in the process.

Likewise, people have no idea how their meat and dairy products are made. A few years ago I went to one of the largest dairy operations in the United States – a company called Milk Source in Wisconsin. They have six large dairies, with 30,000 cows in the region. They have one facility where they bring all of the calves that have been separated from their mothers but are not yet ready to start breeding. They call it Calf Source, and it’s a grid of a few thousand calf hutches, which looks almost like a Legos when seen from the air. If you talk to a dairyman, they would tell you that it’s a very healthy, sanitary and efficient way to raise cows. But when you look at it from above, it’s clear that we’re treating these animals like they are pieces of living plastic or something. To me it’s metaphorical for how we’ve come to make food on a large-scale, commodity basis.

Goats jostle for position at the water pump worked by De Quigigi, a woman in Ejinaqi, Mongolia. Decreasing rains combined with agricultural diversions placed on the river upstream, have turned what was once a desert oasis into a dust bowl.

These operations are called CAFOs – Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations – and can be quite disturbing to see. They are industrial scale operations where animals are genetically engineered or selected to be freaks of nature. These cows have udders down below their knees, they can hardly walk, let alone run from a predator. All their male offspring are being killed, mostly for veal. But it’s an incredibly efficient way to make food. We have bred chickens with super-sized bodies, so big that they can hardly walk. If you compare an American or European chicken to an African chicken, which are scrawny little things, the developed world chickens look like sumo wrestlers with feathers.

It seems really heartless, but if you’re trying to feed 9.7 billion people – which is the projected world population in 2050 – on a limited amount of land, that’s a logical solution. If you are going to preserve wild spaces, you want to limit the amount of food and land resources you use and CAFOs are an incredibly efficient way to do that. Most consumers are unaware of the fact that organic and free-range methods use a lot more resources and have higher rates of mortality.

Over the years, my work has turned me into an accidental environmentalist. I never set out to be an advocate for our planet, but I think that if people know more about an issue, they can make choices that will lead to solutions. Our individual choices add up. For example: Oreo cookies have a lot of palm oil in them and palm oil plantations have caused the loss of much of the natural forested areas in the world. The packages are labeled and if people stopped buying things with palm oil in them, there would be no palm oil plantations.

With only a small percentage of land suitable for agriculture, China makes intensive use of the sea. In the Fújiàn province most of the region’s wild fishery has been depleted so the shallow, muddy coastline has been divided into vast tracts of aquaculture for fish, seaweed and shellfish.

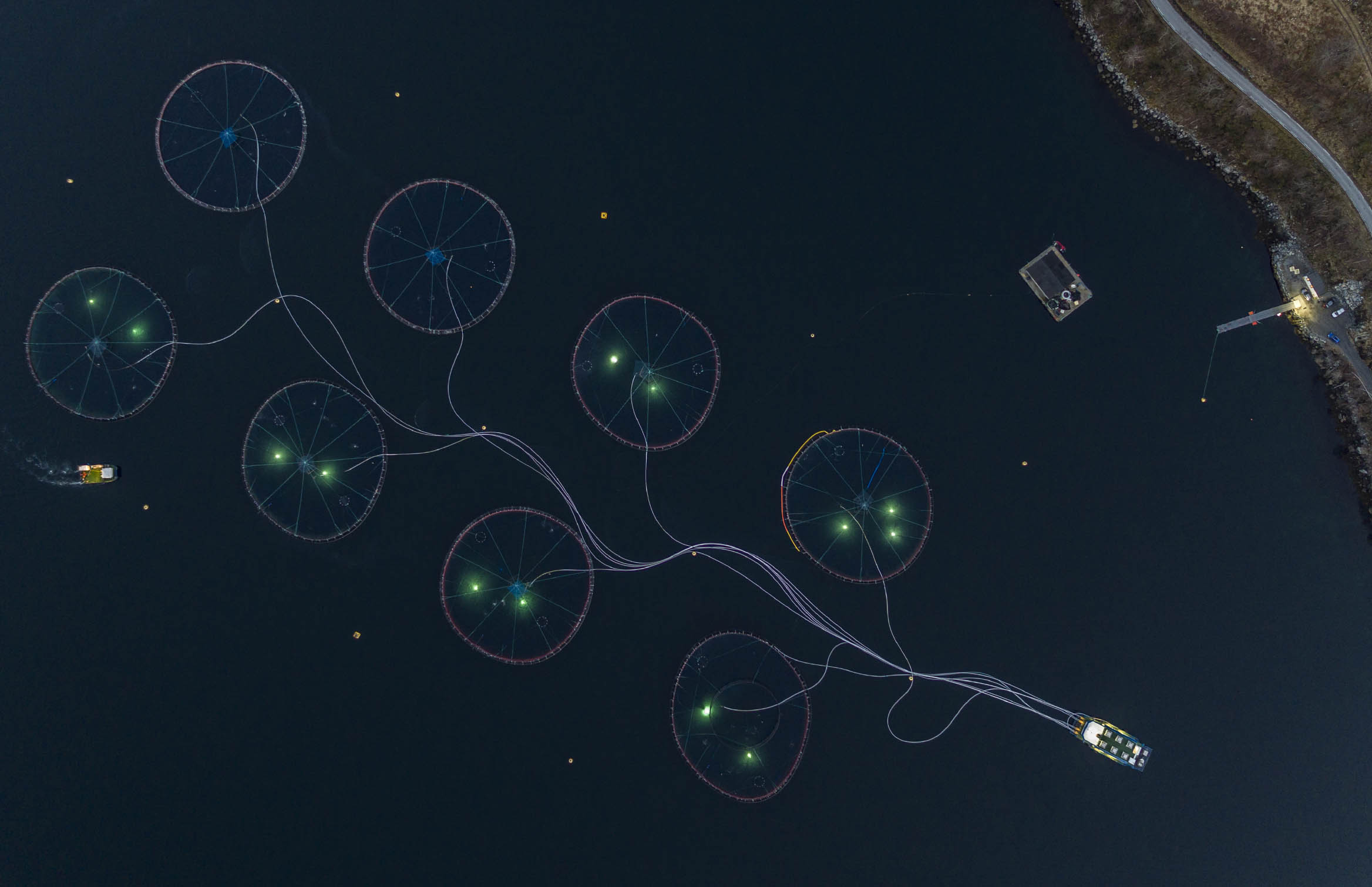

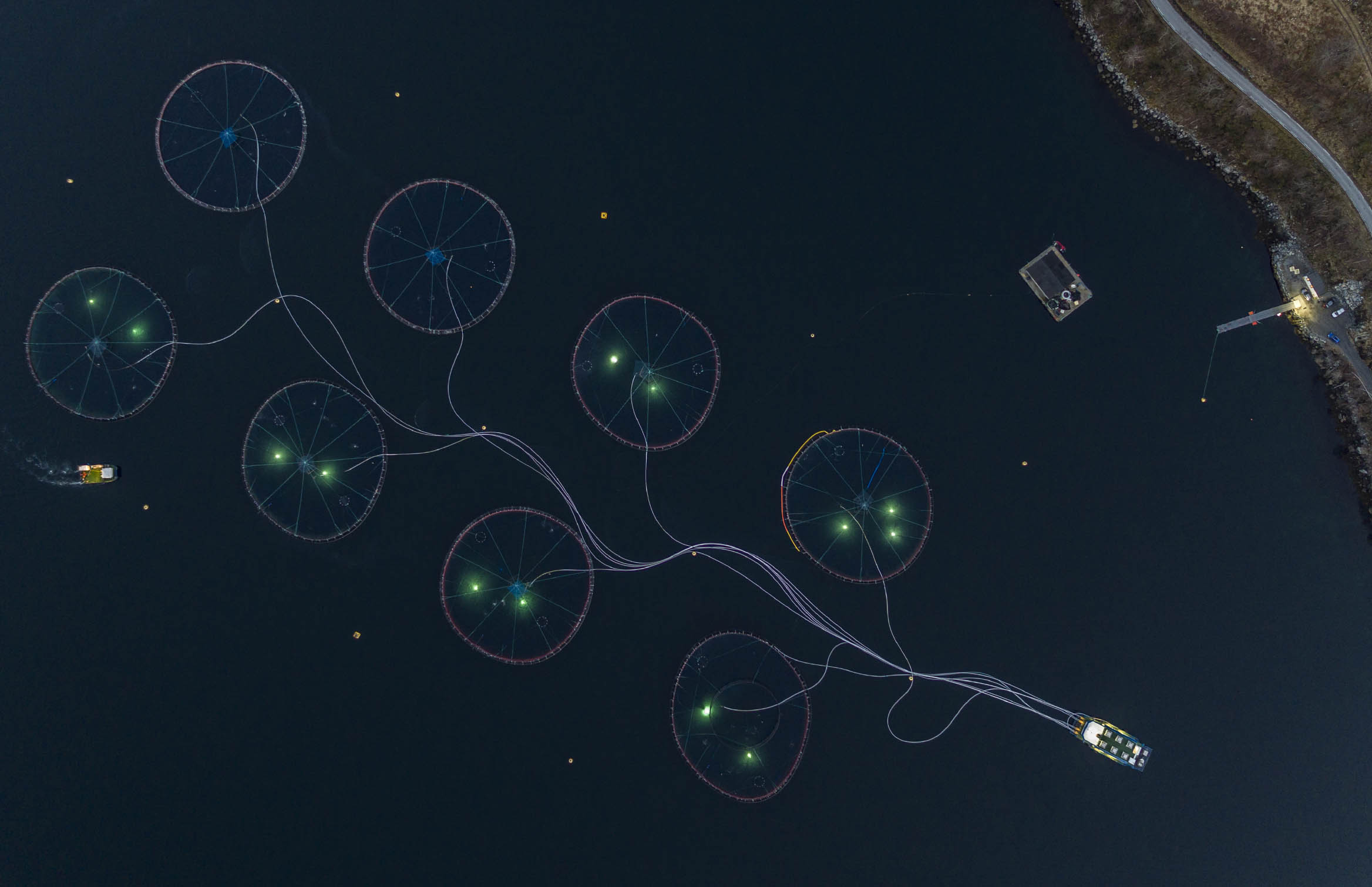

MOWI salmon farm in Sagelva, Hjørund Fjord, Norway, is the biggest grower of farmed salmon in the world. Each of the eight pens holds 200,000 Atlantic salmon.

A new generation of oil palms at the Sapi Plantation in Sabah, Malaysia. The green area on the left was planted a few months earlier – with ninety-eight inches [2,500 millimetres] of rainfall annually and abundant tropical sunlight, ground cover emerges rapidly

Same goes for shrimp. Every pound of shrimp you eat means taking two or more pounds of live fish out of the ocean. Is that really the best thing for our biosphere? We all vote with a fork, three times a day.

I realize that we don’t always have control of what we consume. At home my wife cooks most dinners and we have two teenage boys with us, so I live in a space that I don’t entirely control. We are all in that predicament to some extent, like when you travel on an airplane you are offered very limited choices with very little information. But even with small changes, the cumulative impacts can make a significant difference.

My work on food has led me to the conclusion that we are entering an era of limited resources. We’re getting to the point where we’re running out of fish in the sea and virgin terrain – we’re consuming resources faster than they are replenished – and we have to start thinking about how we can reduce our impact on the world.

The era that scientists are starting to call the Anthropocene started in my lifetime. It’s an apt description for how we’ve reached a point where humans have come to dominate the planet in a profound way. I think we have to rethink the ‘man versus nature’ narrative that dominated when I grew up and revise it to be more like ‘man with nature’. As I get older, I feel it’s my responsibility to try and make people aware of that. I’m sixty-two years old and that’s what I want to do with the time I have left – to be active and running around the world documenting things.

Pools of evaporating saltwater that look like a mosaic floor in the desert area of Teguidda In Tessoum, Agadez Region, Niger.

A lot of nature photography today is about capturing the last really beautiful, pristine, intact ecosystems. And I love seeing that stuff! But that’s not really the majority of the earth’s surface anymore. Even the most remote parts of the world’s deserts are being exploited and wild ocean life is being sucked out of the oceans by big factory trawlers that are removing key parts of the marine ecosystem. We have to tell these difficult untold stories so that people understand.

My friend Paul Nicklen (p. 86) was down in Antarctica and found krill boats that were basically stealing the food from the whales and the penguins, which is part of what is causing massive penguin mortality there. That’s the untold story. As a journalist, when something’s under-reported, that’s what we need to examine.

People love to see beautiful photos of coral reefs and colourful anemones, but to me that’s kind of like nature porn and except for some very remote areas it’s not the norm. I’ve been looking at big industrial tuna boats that hunt schools of fish with helicopters. These things are like James Bond boats going out looking for tuna. That hasn’t really been photographed before and it’s hard trying to get people to engage in these more difficult stories. Maybe I’m a negativist trying to photograph all these problems. It’s definitely easier to sell pictures of a polar bear jumping from one ice floe to another, than it is to sell one of a dying polar bear.

‘The Anthropocene started in my lifetime. It’s an apt description for how we’ve reached a point where humans have come to dominate the planet in a profound way. I think we have to rethink the “man versus nature” narrative that dominated when I grew up and revise it to be more like “man with nature”.’

Flooding in Beaumont, Texas, USA, the day after Hurricane Harvey dumped thirty inches [760 millimetres] of rain on the region in eighteen hours in 2017, causing catastrophic flooding.

‘You find fewer climate change deniers among younger generations. They’re very aware of how our planet is changing and they want to do something about it. That’s really encouraging.’

What I’ve seen has made me reconsider what I eat. When I’m invited to dinner in an Arab village, where they kill the goat behind the kitchen, I still go out and watch them kill the goat because I’m respectfully interested in the process. I think we all need to understand that process better.

Young people get it. You find fewer climate change deniers among younger generations. I think they’re very aware of how our planet is changing and they want to do something about it. That’s really encouraging. Older people get set in their ways and don’t really want to change. That’s one of the great things about humanity. Everybody dies and you have renewal, so our culture just keeps growing and innovating. I think the current challenge is to find ways that we can innovate to lessen the human footprint. Part of that solution is developing new techniques and improving food genetics. I don’t want people to feel guilt-tripped, but I think we should all be more mindful of the consequences of the choices we make.

Thirteen-year-old Rodello Coronel Jr. picks through trash looking for recyclable plastic in the river on the Parola Binondo side of Manila Harbor, home to over 20,000 squatters.

The Coffey Park neighbourhood of Santa Rosa, California, USA, after the 2017 Tubbs Fire. Fanned by strong winds, the fire was the second most destructive wildfire in California history, destroying more than 5,600 structures.