4

Presenting and scheduling activities

You cannot learn to ski by reading a book (or even a hundred books) about skiing. The first time you go on a ski slope you almost certainly will fall down. Similarly, reading this book will not instantly make you an expert at presenting activities for a person with dementia. However, I hope that after reading this chapter you will be able to present an activity successfully. There will be occasions when interactions will not work as well as you imagined they would, and you will learn from these experiences even more than you learn from your successes.

Talk less, watch more!

When communicating with people with dementia remember to talk less and watch more! This principle works well in any situation where communication is difficult, such as where there is a lot of noise and conversation can’t be heard well, when talking with very young children or even when trying to have a conversation with a teenager.

Watch the person with dementia more

Movement is the earliest form of communication we have. Seventy per cent of our communication is based on body language. We learn to rely on language in understanding others but sometimes we over-rely on it, focusing too much on the words and forgetting about body language. For instance, the wife of an unfaithful husband might have realized something was wrong earlier if she had been more aware of how his body language and tone reflected his feelings towards her, rather than just relying on his words.

Language enhances our ability to communicate information about the past and in the future; it lets us converse about more complex and metaphysical topics. Once we’ve developed physical speech, vocabulary and grammar between the ages of one and five, we assume that language is the key to communication. Language is a way of encoding the world, and many of our memories of the world are coded in words. Talking is the part of communication that requires the most conscious effort. Sometimes we struggle to find the right words to say when hearing bad news, when we could use our face and a hug or touch to convey our reaction.

There are many situations where ideas and feelings are conveyed without words. Mime artists and dancers convey complex stories through body language. People with dementia convey a great deal of information through their face and body, how they hold themselves and how they move. We need to watch and read this information, since people with dementia often have difficulty using words.

Tone and pitch are another important part of communication. Babies communicate their moods and needs using a range of sounds such as cries, gurgles and coos. Animals communicate in their social groups and hierarchies through body language and tone and pitch. We can tell if a dog is scared or is being aggressive or friendly through the tone of its bark or whine. When we listen to the person with dementia talk, listen not just to decipher the meaning of the words, but also for the feelings conveyed through tone.

Watch your own mood more

Our moods affect how we behave, and awareness of our own moods helps minimize the chance of inadvertently putting out negative vibes. You may have had a poor night’s sleep and be slightly impatient because of this. Perhaps you have a headache or toothache that is making you grumpy or irritable. You could be feeling sad or angry because of some personal event in your life. However, the person with dementia does not know why you are behaving impatiently, irritably or angrily. They may think your mood reflects your attitude towards them or their behaviour in some way.

Family carers often feel guilt, loss, sadness and even anger towards a person with dementia because of their condition and the stressors of the caregiving role. Professional carers may feel irritated, annoyed or frustrated towards the person with dementia because they see them as uncooperative, rude or ungrateful. These feelings are all understandable given the situation. However, negative feelings get in the way of good interactions with the person with dementia. The person with dementia will pick up on the emotion, even if they don’t realize the reason for it, and react to that emotion.

Another reason to be aware of and manage our own moods is that people with dementia mirror the emotions of those around them. We all do this to some extent, but this emotional contagion is much more pronounced in people with mild dementia than those without dementia. We don’t know exactly why this happens, but scientists think it could be because the person with dementia is trying to fit in socially, and since they are less able to understand the meaning of the words being spoken they compensate by responding to the emotions.

In order to manage my mood, I like to take in a deep breath and hold it, then exhale and relax my body before I enter a room or start an interaction or conversation with a person with dementia. I also find it helpful to stay present in the moment with the person I’m interacting with. If I know I’m in a mood I find difficult to ignore, then I try to choose an activity that is easier for me to present or that is dependent on objects the person with dementia looks at and manipulates, and is less dependent on my interaction with the person with dementia.

Throughout the encounter with the person with dementia, we also need to keep up our awareness of our moods. I find some people with dementia more difficult to be with than others, particularly those with very unpredictable behaviours or strong negative moods. I sometimes find myself getting bothered by repetitive yelling or constant demands for attention. In these cases I remind myself to be calm and that the person is not behaving that way to annoy me, but rather is most probably expressing a need for help, or attention, or company, or reassurance or some physical discomfort. I try to connect with the person in order to try to change their behaviour.

I sometimes feel frustrated or disappointed when an activity does not go as planned and I am unable to connect with someone or they do not seem to want my company or say negative things about me. However, I try not to take these occurrences as personal rejections or as a failure on my part. Rather, I remind myself that things cannot always go to plan and try to use the situation as a learning experience. I try to identify where things did not work so well and plan a new approach the next time.

I find it useful to debrief and talk about an interaction that has brought up an emotional reaction within me, usually with a colleague. If you are a family carer, try to find a relative or friend who will understand and debrief. Debriefing helps us process and deal with negative feelings, and helps us prepare for next time.

Watch your own behaviour more

We are often careful about choosing our words but sometimes we realize that we’ve said the wrong thing and want to take the words back. Occasionally we realize that even though the words were fine, our tone was not appropriate and we apologize: ‘Sorry I yelled at you, I was a bit stressed about getting the job done on time.’ However, we rarely reflect on our body language and what message it is sending. I have never heard anyone say, ‘Sorry I didn’t give you eye contact, but I really didn’t want to hear about your bowels again,’ or ‘Sorry my face looked so dour and stern, I didn’t know how to react to your news.’

People with dementia often forget the words you have said to them and sometimes cannot follow the meanings of the sentences. However, they can read your body language and tone as these are more basic forms of communication. We need to be much more aware of our bodies, faces and gestures and consciously use them to communicate in a relaxed and positive way with people with dementia.

If the person with dementia is sitting down, do not stand over them; this can sometimes seem threatening or suggest that you may not stay long. Ask her permission to sit next to her, and pull up a chair. If there is nowhere to sit I often kneel beside the person. I prefer to sit beside or at a right angle to the person with dementia rather than directly opposite, which can sometimes feel too intimate or intense. It is also easier to look at something together if we are sitting alongside each other.

I described earlier the way people with dementia subconsciously mirror the emotions of those around them, possibly in an effort to fit in socially. We can use this strategy consciously to connect better with the person with dementia by mirroring the speed and intensity of the person with dementia. Match your speed to the speed of the person with dementia. The speed at which they move and talk reflects the pace at which they are thinking, which is also the pace at which they can absorb and process information. This means that we need to slow down when interacting with most people with dementia—sometimes we need to slow right down.

It’s also important to match your intensity of pitch and movement to the intensity and mood of the person with dementia. When someone else is displaying the same mood that we are, or seems to be in emotional synchrony with us, we feel more rapport with and more positively towards that person. We find it easier to relate to them and feel more involved and compatible with people with whom we are sharing the same mood. This occurs irrespective of whether the shared mood is negative or positive. If the person with dementia is moving with a great deal of positive energy, I try to be high energy and happy too. If the person with dementia seems to have low energy and mood, I try to be calm, present and subdued, though not negative in my mood. It can be grating when we are feeling sad or low to interact with someone who is obnoxiously happy.

Obviously we do not mirror the person with dementia’s mood when they are displaying an intensely negative mood, such as anger, distress or extreme sadness. In that case, always model the mood you wish them to be in, i.e. calm and relaxed.

Talk less

Only about 10 per cent of communication is based on the words we use. But these words can be very useful! When communication is difficult we tend to talk more. If the person we are talking to doesn’t understand what we’re saying then we often say it again. Then we may rephrase it and elaborate, and sometimes in this elaboration we talk both faster and louder. And then we say it again ... and again! This strategy may work sometimes but it does not work for people with dementia.

Talk less when communicating with people with dementia. Choose your words carefully and use short sentences and simple phrases. Think before you speak, and make every word count (like a tweet!).

What to talk about with people with dementia

I have had many interesting and enjoyable conversations with people with dementia. However, many people struggle to have a conversation with a person with dementia. Many of our conversations with friends and family start with one person asking a question to which the person responds by reporting their news and there is some discussion around this. The other person then reciprocates by asking a question of the first person which generates more discussion. Both people get to talk about themselves or their lives or interests. This usually happens before the conversation progresses onto other topics.

Here is an example:

If we try to start a conversation following this usual pattern with a person with dementia it often does not succeed. People with dementia often cannot remember ‘news’ to report. They also often do not have the initiative to ask questions of the other person.

Case study

Joy

In the example below, Betty is talking to Joy, who has mild Alzheimer’s dementia. Joy has trouble responding and Betty finds the lack of input from Joy difficult, so she starts just talking about herself and dominating the conversation.

Here are some tips for having successful conversations with people with dementia.

- Don’t ask questions about recent events or questions on topics that require information from their short-term memory.

- Ask about broad topics in their past that they probably remember, but not about specific details of events.

- Ask about topics that you know they like talking about.

- If they bring up a topic, encourage them to talk more about it. Listen for little clues about topics towards which you can steer the conversation. For instance, in our next example with Betty and Joy (see section entitled “Joy”), after Joy talked about Bernie buying her roses when they were courting, Betty could have asked about how Bernie and Joy met, or what their courtship was like, or whether Bernie was a romantic person.

- Ask their advice. Ask their opinion on both small dilemmas and big problems. ‘What should I cook for dinner tonight?’ or ‘Should I let my sixteen-year-old daughter go on a date with a boy?’

- Talk about things in the present—things you can see, hear, smell and taste—the scene in front of you, the sound of the birds, the smell of the flowers or the taste of the cake you’re sharing.

- Don’t correct the person with dementia or argue about facts. If the person with dementia is talking about his past and says he has no grandchildren when he actually has three, it would be critical and disempowering to tell him he is wrong or has remembered that fact incorrectly.

- Remember that the person has difficulty with memory and other aspects of thinking, but they are not stupid! Don’t talk to them as if they are stupid.

- Don’t try to use absolute logic to convince them of something—though sometimes logic works if consistent with their world view. For instance, I was told a story about a man with dementia who was trying to leave home because he was convinced he was going to be late to work to meet the delivery truck. He wouldn’t believe his wife when she said that he no longer went to work. However, in keeping with his current world view, his wife told him the delivery truck driver had called, had explained they had broken down and were running late and would not arrive until the following morning. He consequently calmed down.

Case study

Joy

Here is an example of a conversation where Betty has taken a different approach to having a conversation with Joy. She does not rely on Joy’s memory and creates opportunities for Joy to talk about topics she is interested in. She also does not expect that Joy will invite her to talk about herself. Many of the meaningful conversations of people with dementia are based on their established knowledge either of facts or their personal history. This is elaborated on further in the section on reminiscence.

Here is another example of a conversation between Betty and Joy. Betty starts the conversation based on the weather, and asks Joy a general question not reliant on short-term memory.

It is okay to lie to a person with dementia?

The ethics of lying are complex. My opinion is that perfect honesty is less important than respect, compassion and empathy. I take the utilitarian philosophical perspective that lying is acceptable when the resulting consequences maximize benefit or minimize harm, though it can be often very difficult to foresee what the consequence of a lie is going to be, and in those circumstances it is difficult to decide whether or not it is acceptable to lie.

I believe that persons with dementia should be protected from the outside world if they cannot cope with it. My pragmatic experience is that sometimes telling the person with dementia the truth does not help them and can actually distress them more. Telling the person with dementia a falsehood consistent with their beliefs may be better for their wellbeing. But withholding knowledge from the person with dementia takes away choices from them, and takes away their human right of freedom of information. So I try to foresee the consequences of the lie.

Take, for example, the issue of whether to remind a woman with dementia that her husband has passed away if she has forgotten this fact. If told, she will have to relive the experience of the grief of the initial loss of her husband and may be happier and better off continuing to believe her spouse is still alive. So in this case I would not usually remind the person that their spouse has passed away. However, if the person with dementia needs to make decisions about their life or estate, and needs to know that her husband has passed away as part of these decisions, then I would remind her about her husband’s death.

There are some circumstances where, I feel, it is ethically acceptable to lie to a person with dementia, and in such cases you would need to balance protecting the feelings of the person with dementia with their right to know and any loss of freedom to make choices based on the information.

Status, choice and letting the person with dementia give back

Social status refers to the rank or position of a person within a group, where a group could be just two people. Social status can be ascribed based on age, wealth, sex or ethnic group. Status can also be achieved through accumulation of knowledge or achievements. Within any group interaction, different people may have different levels of status dictated either through formal roles (e.g. the boss or the nominated leader, the group chair, the parent) or roles constrained by the situation (e.g. irate customer in relation to customer service officer, bank manager in relation to loan applicant), past experience with the relationship (e.g. old friends where one person is more dominant, older brother in relation to younger sister) or ability in the situation (e.g. being knowledgeable about cars versus ignorant when a car breaks down). Sometime status is overtly awarded (e.g. when a guest of honour is announced) but more often status is implicitly conferred or claimed by the way people interact. Social status is often communicated through subtle behaviours: we establish an unconscious structure of deference and social value. Status reflects who is in charge, and acknowledging their order in the social hierarchy keeps social relations stable and harmonious.

Within any group the social status of a person may change depending on the situation. For instance, for the duration of a team-building exercise the social status of the boss may be lowered and he may have equal status to the other team members during the exercise. Similarly, during family games adults become equal with the children for the duration of the game. Friends and relationships often have a balanced shifting of status depending on the situation and activity.

People with dementia almost always experience a loss of social status. They stop working and lose status associated with their work role. Socially, because of their loss of cognitive abilities, they are less able to make a contribution through work or conversation and lose status this way. Sometimes people with dementia are talked over or talked about as if they are not there, which further diminishes their status. If you have an established relationship with the person with dementia then you would also have your usual status roles. This may have changed since the person developed dementia. Reflect on this status, and whether you want to give the person with dementia greater status during some of your interactions with them.

I try to confer the people with dementia I interact with equal or higher status during our interactions. There are several ways in which I do this. Firstly, I use body language, bringing myself to the person’s level, making eye contact, not taking up too much ‘space’. I am attentive rather than dismissive. People with high status often look past rather than at those with lower status, as if they are not worthy of their full attention. People with higher status also tend to look down on those with lower status (e.g. a king on a throne) and take up lots of physical room.

Secondly, I ask the person with dementia their opinion and give them choice. People with high status tend to tell those of lower status what to do—for instance managers give instructions to their staff, fathers reprimand their children and doctors advise their patients. Rather than telling the person to do an activity, I ask what she thinks and offer her choices. I ask for permission to sit down and talk with her, I invite her to do activities with me, I ask for her help. At the end of our interaction, I thank her for her time, tell her I enjoyed her company (if I did) and ask if I can talk with her again.

Thirdly, I give the person with dementia the chance to give back. Humans have evolved to be social creatures. Those of our ancestors who could cooperate better with their social group survived, possibly because they hunted better and defended themselves against predators better. Part of being social creatures is that we’re compelled both publically and internally to be reciprocal in our behaviour, meaning that we’re expected to help others who help us. Most of us feel that we need to repay favours, and failure to do so brings slight feelings of inadequacy or guilt. For instance, I feel guiltier forgetting the birthday of a friend who always remembers my birthday than forgetting the birthday of a friend who never remembers mine.

Some people with dementia feel they are a burden to their family and others, particularly because they are not contributing in any way. Giving people with dementia the chance to ‘give back’ evens up the social debt they may feel. To let the person with dementia give back, I may ask for their company for an activity, their advice during a conversation or their help in completing a task. This gives the activity/conversation/task added meaning because there is a social reason to do the task, i.e. fulfilling my request. I also acknowledge their contribution, listen to their advice, compliment their efforts, laugh at their jokes and enjoy their company. I appreciate what they have given back. We usually think of giving back as physically returning a favour, but giving back can also include returning positive energy and feelings and being generous in interactions with others.

Presenting activities for persons with dementia

There are a number of things you can do before beginning the activity to increase your chances of success.

Prepare

Before you start, make sure you have all the equipment you will need for the activity and mentally rehearse what you are going to do.

For instance if you are going on an outing, make sure that before you head out you have the address and location and have looked over a map, and you have keys and money, food and water if needed. It can also be useful to know whether there are toilets at your destination. If you are showing the person a book, look over the pages first and prepare some questions or comments to start the conversation. You may also have a back-up or alternative activity prepared.

Set the scene

Before trying to engage a person with dementia make sure he is comfortable. Is he hungry? Does he need to use the toilet? Is he in pain or feeling unwell? Make sure that his physical needs are attended to otherwise these concerns will reduce his ability to concentrate on you and the activity.

When you start talking to the person with dementia, make sure he can hear you and see you properly. Has he got his glasses or hearing aids on if he needs them? Sit on his ‘good’ side in terms of sight and hearing.

Minimize distractions. Switch off the television or radio. Clear the table if you are sitting at the table to do an activity. Make it easy for him to concentrate on you rather than spending energy blocking out competing information.

Connect with the person and invite them to participate in the activity

Make eye contact with the person with dementia, make sure you have their attention and say their name in greeting. Smile. I like to use the person’s name frequently during our interaction; this keeps their attention and helps maintain rapport.

Unless you are sure that the person with dementia knows who you are, introduce yourself. Give your name as well as your relationship. If you simply say ‘Hi Mum’ they may not remember which child you are, or your name. Whereas if you say ‘Hi Mum, it’s Julie’ then you’ve reoriented them to who you are.

Always give the person with dementia the choice to participate in the activity. In inviting the person to participate, think of why he might want to start the activity. Is the activity, at face value, of interest to him? Could he agree to start it because he likes doing something with another person? Could he agree to start it because he would like to help you?

Pitch your invitation based on the reason you think the person with dementia might participate in the activity. This may simply mean that you ask the person if they want to participate in the named activity, or if they want to participate in activity A or activity B (giving them choice at the same time). Alternatively you could ask the person for his help, or if he would like to do something together with you. Another approach is to engage him in conversation first to establish rapport and a relationship and then, when he seems to be in a receptive mood, invite him to participate in an activity together. Yet another approach is to start doing the activity where he can observe you and then invite him to join in after he has observed you—or he might even spontaneously join in. It is not usually a good tactic to ask the person to do the activity ‘because it is good for you’. Many of us don’t do things just because we have been told they are good for us.

If the person with dementia repeatedly refuses invitations to participate given through different approaches and for different activities, I would then reconsider the choice of activities, the invitation to participate and the person making the approach. Try to see if a different person, a different approach and different activities makes a difference and build from any small successes. A small success would be the person agreeing to participate in the activity, even if he quickly loses interest. In this context it would be worthwhile investigating and understanding any clinical causes of this resistance such as depression or chronic pain, or historical explanations such as a lifelong dislike of strangers.

Present the activity

During the activity provide appropriate support, monitor the person with dementia’s response and modify the activity if needed; additionally, provide consistent positive feedback and follow his lead.

During the activity remember to use the communication strategies described earlier. Talk less and watch more. Watch and assess the person’s reactions and interactions, and modify the activity accordingly. To modify the activity, use the principles of task analysis described in Chapter 3, such as taking away a step or providing more support. If you decide to abandon an activity, always offer an alternative activity that you can do together. You don’t want to leave the person with dementia feeling as if you’ve left because they failed at the activity.

Judging the success of an activity

Throughout your interactions with the person with dementia, observe her body language and facial expressions and let this guide your interactions. People with dementia have less control of their emotions and can be more unpredictable in their reactions, so we have to be extra aware of their mood when communicating with them.

The signs of engagement of someone with mild dementia may be obvious. However, I am often asked how to tell whether someone with severe dementia is engaged with and enjoying an activity. Below are some signs of interest and engagement for people with dementia.

Signs of engagement and interest

- Looking at you or the objects you are presenting—he or she may turn their head or lean forward or make eye contact.

- Nodding, clapping or responding in other ways.

- Talking—the words might not always be clear or make sense, but talking indicates they are responding to you.

- Touching, holding, approaching you or the object you are presenting.

The person with dementia may not follow an instruction or pick up an object but this does not mean they are not interested in interacting with you if the other signs of engagement are there. If you think the person has not attended to what you presented, you could either repeat it or try another approach.

Signs of disengagement, boredom or tiredness

- Looking away or down for a prolonged period.

- Getting up and moving away, leaning back, pulling away.

- Closing their eyes (except if appropriate, such as when listening to music or a story).

- Doing something else—the person may still want to interact with you but might not be interested in the activity or not understand what you want them to do.

- Talking about something else—the person may want to interact with you but might not be interested in the topic or might be unable to follow your conversation.

Signs of enjoyment

- Smiling, laughing.

- A peaceful or calm expression.

- An expression of concentration.

Signs of distress

Give regular, consistent, positive feedback

Activities sometimes have ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ responses or ways of doing things, but almost all the time it does not really matter whether the person with dementia’s response is right or wrong. Even in a task where the outcome could be affected if they do the activity incorrectly, such as when making a cup of tea, it does not matter if the end product is not ideal.

Give regular, ongoing praise. Useful phrases include ‘good work’, ‘well done’, ‘nice job’, ‘that’s great’, ‘super’ and ‘thank you’. If the person has done something incorrectly, continue to use the same phrases in your feedback. If the person knows they’ve done it incorrectly or cannot do it correctly and becomes frustrated, encourage them to try again and support them to succeed. Say, ‘That’s okay, it is difficult, so let’s do it together.’

Follow their lead

Sometimes when a person with dementia does something ‘wrong’, rather than ignoring it, this can be an opportunity to take the activity into a different direction than planned. For instance you may have dealt the cards for a simple card game such as snap, but the person with dementia might instead start sorting the cards or building a card tower with the cards. Instead of bringing them back to the task of snap, go along with what the person wants to do and support them arranging the cards into suits or building the tower.

Dealing with strong negative reactions

A risk we take in any interaction with another person is that they could react negatively. It can be hurtful and upsetting if I’ve put time and effort into coming up with an activity and the person with dementia yells abuse at me or is violent in response.

Even if I’ve been watching carefully for warning signs such as restlessness, anxiousness or agitated behaviour, I might not have been able to predict the person with dementia was going to have a strong negative reaction. Or I might have noticed the signs but not been able to calm the person down and their behaviour has escalated.

If this occurs, firstly I try to stay calm. If there is any chance that I or someone else is in danger of being hurt, I reduce that risk by removing myself or the other people present or by getting help. Listen to what the person with dementia is saying, and watch what she is doing, and try to figure out what has made the person upset. If possible I try to fix what has upset the person. Even if you can’t figure out the cause, reassure the person and distract her. If more appropriate I give her space. If this happens to you, don’t take it personally; remember that their reaction is not something you have control over, even if it directly occurred in reaction to your behaviour. It is really important to discuss the incident with someone else (debrief) afterwards. Reflect on what you would do differently in the future.

Often, the person with dementia will forget the incident and be happy to have your company again on another occasion. But be cautious when approaching the person the next time.

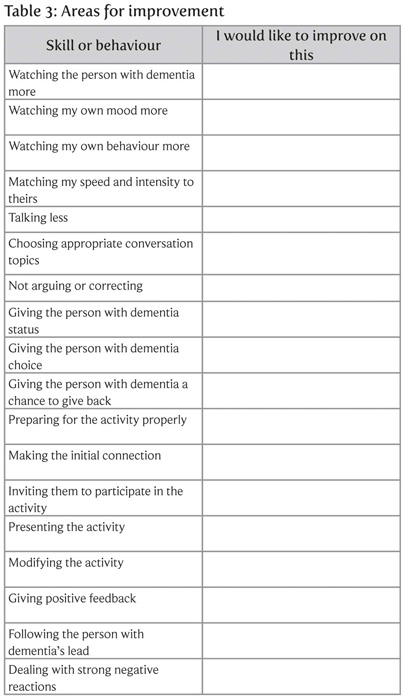

Self-reflection

Please think about your last few interactions with the person or people with dementia you care for. In the table opposite indicate the areas that you would like to improve, and then work on each skill until you are satisfied with your performance. Each time you present an activity it is also worthwhile briefly reflecting on how you have gone and what things you could improve the next time. Professional carers could include these reflections in their care notes.

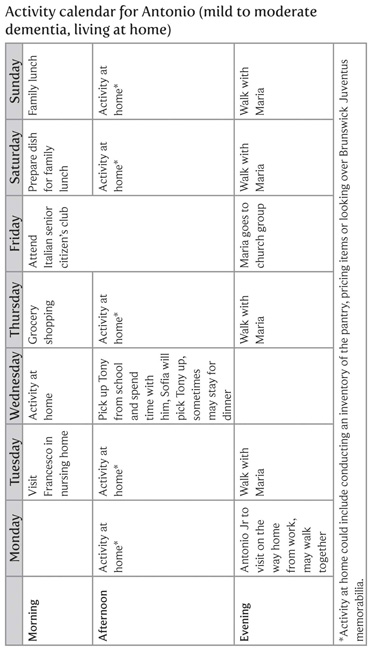

Scheduling activities

It is a good idea to plan when you’re going to present an activity. The timing may be based on certain times of the day when the person is likely to be in a better mood or have better attention or higher energy. You might also plan activities to meet the person’s needs, for example if he tends to feel lonely after a visit from a friend or relative you could have an activity prepared for after that visit. Or you might choose a time when the person with dementia seems to have excess energy and be pacing or doing repetitive things, and give him an activity that lets him channel that energy, such as singing songs or going for a walk. Some people with dementia can sometimes be unpredictable in public, so you might want to bring an activity to engage them in situations where they may be bored such as in a doctor’s waiting room.

Activity calendars

It would be great for people with dementia to do a meaningful activity every day, and even several times a day. An activity calendar will help you plan activities and can be written into the existing family calendar or diary, or specifically drawn up. If multiple people are involved in the person’s care, then an activity calendar will let everyone know what is happening, or has happened, for that person.

For family carers, writing out the calendar may seem like a lot of planning, however planning the activities means they are more likely to happen regularly and you don’t need to think ‘what next?’ all the time. You can also see if there is a ‘spread’ of different types of activities. If you have a friend or paid carer come to care for the person with dementia to give you a break, then you can plan some activities they can do together. Having a regular activity schedule also provides a stimulating routine for the person with dementia. Activity planning on a monthly basis also gives you an opportunity to brainstorm new ideas for activities the person would like, based on your experiences of the previous month. Make the plans as tailored and specific as possible, and try to get a mix of activities that are cognitively stimulating, involve socialization and physical activity. And of course they should all be meaningful and achievable!

For professional carers, activities should form part of care plans, although I have rarely seen individualized activity plans. Tailoring activity calendars as much as possible (with the input of family caregivers and the person with dementia) will maximize the chance that the person will participate willingly, successfully and frequently. Nursing homes have the challenge of limited staff hours and resources when trying to cater for every individual resident. Nursing homes usually have activity programs for the whole facility or different sections of the facility, however since it is unlikely that many activities on this program are appropriate for the person with dementia, a personalized activity calendar would provide much better recreational care.

Examples of personalized activity calendars

On the following pages are some examples of what personalized activity calendars might look like for three of the people we are following in our case studies: Joy, Antonio and Ruth. In keeping with taking into account the thinking abilities of the person with dementia, note that it is likely to be more possible to plan a greater number and diversity of activities for the person with mild dementia than for those with greater cognitive impairment. People with dementia usually do not mind repeating activities they like.