John Reid was born in Toronto on October 6, 1913, the only child of Olive Gibson Reid, a 28-year-old tailoress, and Harry Edgar Reid, a typesetter soon to turn 30.

Olive and Harry were the children and grandchildren of immigrants. Harry was born in the town of Innisfil, Ontario, on the west shore of Lake Simcoe, in 1883. His father, Joshua Reid, was an Ontario railway worker whose paternal grandparents were landed gentry in Borrisokane, Ireland, and whose parents, William and Margaret, fled the depression in Great Britain and Ireland following the Napoleonic Wars and were granted land in Weston, Upper Canada, in the 1830s. Harry’s mother, Mary Jane Killen, was of French Huguenot descent and the daughter of James Killen, a millwright from Dumdruff, Ireland, whose noteworthy grandfather, also James, fought under Britain’s Lord Nelson in the Battles of the Nile, Copenhagen, and Trafalgar. The Killen family immigrated to Canada in 1873 and settled in Innisfil, where Mary Jane Killen and Joshua Reid met and married in 1876. Harry was the fourth of their seven children.

John Reid’s mother, Olive Gibson, was born in 1885, the daughter of Thomas Gibson, a Toronto teamster, and his wife, Mary-Ann Thorogood. Thomas Gibson’s parents emigrated from England to Canada West in the late 1840s and opened a shop on Charles Street in Toronto. Mary-Ann Thorogood’s English father, Joseph, and her American mother, Theresa, emigrated from the United States to Toronto in the 1850s, where Mary-Ann was born in 1862 and married Thomas Gibson in 1881. Olive was the third of Thomas and Mary-Ann’s five children.

How Harry met Olive is unknown, though a possible connection is Joseph Gibson, one of Olive’s two older brothers. By 1908, Harry Reid, now 25, had moved from his first job setting type by hand at the Muskoka Herald, a small-town newspaper co-founded by his uncle in Bracebridge, Ontario, to the typesetting staff of a large Toronto daily. Joseph Gibson, a year older than Harry, worked as a machinist and may have been employed at the same newspaper, servicing its printing presses and Linotype machines.

Churchgoing was another way of meeting members of the opposite sex, and given their neighbourhood proximity this, too, could have been the case for Harry and Olive. By 1911, the entire Reid family had moved from Innisfil to Toronto and was living at 279 Dupont Street, just west of Spadina Road, a 15-minute walk from the Gibson household at 784 Euclid Avenue. One of the Annex neighbourhood churches was a possible point of contact.

However they met, Harry and Olive were married in Toronto on March 12, 1912, and set up house at 226 Margueretta Street in the city’s west end. A year and a half after the wedding, Olive gave birth at the new Toronto General Hospital on College Street, the institution where her son — christened John Anthony Gibson Reid, but almost always known as Jack — would train as a doctor in the 1930s.

Jack Reid, age three.

Jack Reid, 226 Margueretta Street, Toronto, circa 1918.

Jack Reid’s childhood was happy and secure. By the time he was born, his father had logged five years of experience operating Linotype machines, the ingenious keyboard-controlled type-setting device with an astonishing 5,000 moving parts that was revolutionizing the publishing industry worldwide. In August 1918, the summer before Jack turned five, Harry Reid left the newspaper and landed a job at Canadian Linotype Limited itself, the American company’s Toronto office, which sold and serviced Linotype machines across Canada. Here he would rise from novice salesman to sales manager within four years, then to branch manager in 1925 and in the 1930s to vice-president and manager for Canada. Even during the Great Depression, Harry Reid’s job was assured.

Shortly after the First World War, the family moved to 396 Durie Street, where Reid attended nearby Runnymede Public School, grades one through eight. From the beginning, he was a great reader. The Boy’s Own and CHUMS annuals were consumed with gusto, as were the many novels of G.A. Henty, featuring historical heroes from Britain and its empire. These yarns and later stories from the Great War likely inspired the battle stratagems the boy employed when he set up his ever-growing collection of lead soldiers — galloping cavalry, kilted Highlanders, Irish Guards in scarlet tunics and bearskin hats — later reinforced by First World War–vintage khaki-coloured infantry crouched behind machine guns or charging the enemy with fixed bayonets.

His literary bent appeared early on. At the opening of the new wing of the Art Gallery of Toronto in February 1926 (today the Art Gallery of Ontario), Reid, age 12, won first prize in Runnymede School’s writing competition for the best student essay on the painting entitled A Canadian Soldier (the prize itself was a picture — a small, poorly tinted reproduction of fields lined by poplars in a Flanders landscape still untouched by war).

Jack’s first salute.

Nourishing her son’s interest in cultural matters with her own was Olive, who encouraged Reid’s reading, writing, and musical talents, and took him to the public library and to stage shows and movies of the day. Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Joe E. Brown, and especially Harold Lloyd, the suave, bespectacled, stunningly athletic comedy star of the silent screen, were childhood preferences of young Jack.

Family outings were popular in Toronto in the 1920s, and on these forays, Harry Reid led the way. Toronto’s Sunnyside Amusement Park and the Toronto Islands were popular spots, and favourite days for the Reids were communal picnics with family and friends where races, games, and ragtag baseball were part of the fun. A natural organizer of such razzmatazz, Harry Reid was usually at the centre of things, including the softball diamond where, as pitcher, his underhand fastball was renowned. In later years, Harry embellished these exploits and entertained the young with tall tales of his prowess in the father-and-son competitions: chugging to victory in the egg and spoon and potato sack races, little Jack flying in his wake as they crossed the finish line in first place. Harry Reid also had his musical side, a Pied-Piperish pleasure in gathering children for singalongs of such ditties as “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” and “Bicycle Built for Two” — Harry conducting, the children chiming the beat on glass jars with old nails as they raggedly sang the tunes.

In the fall of 1926, Harry and Olive Reid enrolled their son at University of Toronto Schools (UTS), a special “laboratory” high school established on campus in 1910 by the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Education for teacher-training and curriculum-testing purposes. Here he excelled as a student and made the close friends — Doug Dadson, Frank Woods, and Leney Gage — he would keep throughout his university years and beyond. In the Class Notes section of the 1927 edition of the Twig, the UTS school magazine, Reid’s traits of independence and self-direction are wryly noted in the doggerel of a classmate:

A very fine student is Reid,

He comes of a ponderous breed,

He never hurries;

He never worries;

This ponderous student Reid.1

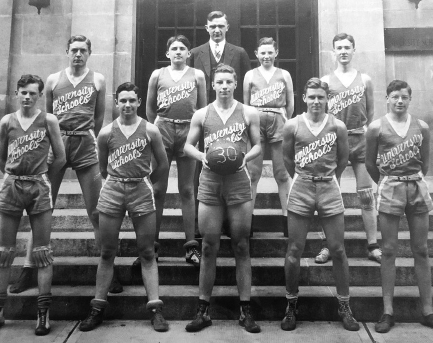

His extracurricular activities at UTS were basketball, track and field, and tennis, as well as working on and writing for the Twig. Due to preadolescent chubbiness (he weighed 148 pounds by the age of 11), Reid welcomed the growth spurts of teenage years (he would reach six feet in height) and committed himself to a physical regimen that in one form or another, even in prison camp, he kept up until his final illness in the 1970s. In 1930 and 1931, he captained the UTS basketball team, and in his last two years, he competed in singles and doubles tennis (partnered with Doug Dadson), advancing to the quarter- and semifinals, respectively.

His road to tennis mastery revealed Reid’s solo approach to new challenges. Taking up the game from scratch in his teens, he borrowed a book of tennis instruction from the library and spent the summer developing his strokes by volleying balls off a brick wall at Runnymede Public School for hours a day. Only after perfecting his shots did he take to the court against live opponents.

University of Toronto Schools (UTS) basketball team, 1930. Reid (front row, centre), Doug Dadson (front row, second from right), Leney Gage (back row, left).

With his strong literary interests, Reid continued his omnivorous reading throughout his high school years and approached this part of his self-education with similar practicality. Some of Charles Dickens’s more sentimental novels, for example, he was inclined to leave unopened. But Dickens was part of literature’s Western canon, so Reid dutifully read the complete works. When gripped by a story, he found it hard to put down. Preparation for a set of high school exams, he said, was almost sabotaged by John Galsworthy’s The Forsyte Saga. His taste in poetry was expansive, ranging from the Latin classics and 19th-century romanticism to contemporary works — Requiem, for example, a Great War– inspired collection composed by Humbert Wolfe, a now forgotten Italian-born British poet of the interwar period. Something of Reid’s quirky sense of humour and his ready appreciation of the lovable and ludicrous can be drawn from his early and enduring affection for Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy.

As well as reading widely, Reid was writing poetry and stories of his own during high school — clever if derivative juvenilia such as his Gothic-style poem entitled “A Slumbering Legend,” which begins:

Edged by the outflung brightness of the sky,

A blot, like some dark moon in strange eclipse,

Vines lingering o’er its skeleton like a sigh,

Bowed down with age, the ruined castle sits …2

Or his Wordsworthian rhapsody, “May She Return?”:

A fairy path I happ’t upon

That led me drowsily afield,

A trace that stretched into the dawn,

As if by wind-borne feet unreeled …3

Noteworthy is “Impulse,” a short story written and published in the Twig in 1929 when Reid was 16, which strangely foreshadows the nightmare he would experience as a prisoner of war in Hong Kong and Japan more than 10 years later.

“Impulse” tells the story of two newspaper reporters — the narrator and his associate Richard Roberts, whose assignment brings them to the dark, forbidding house of To Fang Chu, a prominent member of New York City’s Chinatown and a man reputed to hate white men “like poison.” The editor of the Daily Tribune wants his reporters to get Chu’s reaction to the elopement of Chu’s daughter, who has run off with “Renny Basil, idol of New York society.” The tone of the story is macabre. As the reporters knock on Chu’s door, the narrator thinks he glimpses a ghoulish face leering down from an outcrop of the gable. Once admitted (at their knock, the door swings silently open of its own accord), they make their way down dim corridors into a back room where they are confronted by a smirking To Fang Chu, who seems to be expecting them. Suddenly, the only light in the room crashes to the floor. The narrator hears his partner cry out in the darkness and in panic makes a run for the front door. He takes a wrong turn and by mistake shuts himself inside To Fang Chu’s security vault:

Instantaneously the world was cut off. Every sound ceased…. I felt for the door, its edge. A smooth wall greeted my shaking fingers. Turning, I started on, and stepped into another wall. Of course, the passage branched off. Two steps to the left and I was again halted. Panicky, I turned and ran madly to the right. And then my worst fears were realized. Four full paces and a glassy surface prohibited my further progress. In the next moment all the gruesome tales of Chinese tortures that I had ever heard flashed into my mind. Insanely I assailed those bare, defiant walls. Kicked and beat them until I was exhausted. It seemed hours since I had slammed that door. And then my frantic, strained nerves impressed upon me that it was becoming increasingly hard to breathe. This realization only urged me to greater efforts. But a few moments later I stopped, panting. Then remembering that warm air rose, I knelt down and breathed a bit easier. But only too soon it again became close, stifling. I was choking. One last assault on those unforgiving walls. Then — oblivion.4

Reid won the T.M. Porter Special Scholarship for English and History in 1930 and the Special James Harris Proficiency Scholarship upon graduation from UTS in 1931. That fall, Reid and his school friends, Doug Dadson, Frank Woods, Leney Gage, Alfredo Goggio, and Bruce Charles, entered the honours bachelor of arts program at University College, University of Toronto. For Reid and Charles, who had chosen to become doctors, this four-year undergraduate degree was part one of the University of Toronto’s biological and medical sciences courses, a seven-year program.

Thanks to Harry Reid’s position at Canadian Linotype, his son not only could afford tuition but drove to school from his home in the west end in a big blue Buick of his own. As far as his friends could tell, Reid always had money, or access to it. For others, the effects of the Great Depression were devastating. By 1931, Doug Dadson’s family was in such financial straits that the $100 university tuition fee was beyond their means. Reid, “a very kind man, without show,”5 said Dadson, gave him the money for first-year university.

Before the stock market crash of 1929, the Reids moved from Durie Street to a corner property at 79 Humber Trail, a spacious house a few minutes walk east of the Humber River and its forested valley. Here at 79 Humber Trail, the last house the Reids would share as a family, Doug Dadson, Frank Woods, and Leney Gage would visit for evenings of bridge, conversation, and cigar smoking. Dadson and Woods remembered the Reids as a close-knit family with little connection to neighbours on the street. Harry struck them as a positive, friendly, uncomplicated man, busy with his work at Canadian Linotype. They found Olive attractive, gentle, and welcoming, with a very close bond to her son. “She was quiet,” said Dadson, “but her warmth permeated the home.”6

As an only child, Reid matured early. He struck his friends, who had siblings, more like a close associate of his parents than a son. He dressed well. Already a skilled bridge player (he didn’t sort his hand — one glance and he was ready to bid), Reid excelled at all card games. He was an early devotee of the New Yorker, an admirer of its contributors, such as James Thurber and Ogden Nash, for their inventive whimsy, and of Noël Coward, that consummate sophisticate, for his stylishness, playwriting, and music (Reid played the piano and apparently wrote tunes of his own). Horse racing was another of Reid’s early interests, a visit to the track entertainment of a different sort.

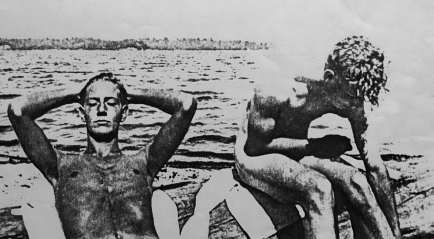

On the beach at Foot’s Bay, early 1930s. Leney Gage (left) and Jack.

Something of a loner, Reid could also be a receptive and reflective friend. Doug Dadson occasionally stayed at 79 Humber Trail when Olive accompanied Harry on his business trips and describes Reid as someone he could talk with intimately on any subject. Sometime during first-year university their conversation must have turned to summer holidays because it was Dadson who provided the entrée for Reid and their other friends to spend a string of summers at Foot’s Bay on the Muskoka Lakes — what would become golden interludes in their university lives. It was also where Reid met Jean Hodge in 1933, the woman he would marry just before the Second World War.

Foot’s Bay in the 1930s was a sparsely settled tourist community at the southwest corner of Lake Joseph in Ontario’s Muskoka region. One of the regular summer residents was Doug’s uncle, Dr. Thomas Dadson, a history professor at Acadia University in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, whose Baptist minister father, Ebenezer, had bought an extensive shoreline property before the First World War on which Thomas later built a huge summer home called Cranbrook, named after the market town in Kent, England, where Ebenezer was born.

Down the shore from Cranbrook stood a rambling, pleasantly shabby boarding house-cum-hotel called Staney Brae (“Stoney Hillside”). It was run by a wiry little Scottish spinster named Georgia MacKenzie with the help of her companion, Miss Ray, and Miss MacKenzie’s nephews, Alan and Dunny. In 1931, Doug Dadson, who often stayed at Cranbrook, heard from his uncle that a waterfront shack on Miss MacKenzie’s property was vacant and would be available the coming summer for a pittance. At this news, Reid must have pricked up his ears. Inquiries were made, the rental was arranged, and after the university year finished in June 1932, Harry and Olive Reid chauffeured their son and Frank Woods to Foot’s Bay. Several hundred yards along the lake from Miss MacKenzie’s hotel sat their tiny destination. Although to older eyes, Olive’s in particular, it looked disconcertingly primitive, Reid and Woods were delighted by the place and its surroundings.

About 10 feet square, shrouded by trees on three sides and steps from the water on the fourth, the shack was fronted by a narrow, roofless porch and furnished inside with a table, a few chairs, three cots lining the walls, and an old sheet iron stove. Over the ensuing five years, this would be home for Reid during the three-month summer break from university, while Dadson, Woods, Gage, and other friends came and went in changing combinations.

“They were marvellous summers,” said Frank Woods many years later. “We had a canoe and a rowboat. We ate well — steaks and chops from MacDonald’s Store, and the washing up was easy. We just left the dishes and utensils in the water by the shore and they were clean by the next meal, washed by sand and water motion.”7

Dark and cramped, the shack was mainly for sleeping. Days were spent on the water and at a splendid sand beach at the nearby entrance to Stills Bay. Photographs show Reid and his friends swimming in halcyon summer weather, sunbathing on the beach with an old log as bench and backrest, reading on the steps of their porch, or gathered around campfires during canoe trips they took to other parts of Muskoka.

For regular supplies, they paddled or rowed to the store at the Foot’s Bay public dock, 20 minutes away. Fish were plentiful. Lake trout were especially prized, and a favourite Reid pastime, especially when on his own, was to paddle out to deep water in the evening, drop a line, then stretch out on the floor of his drifting canoe, light a cigar, and watch the fading light and first stars appearing until a fish struck. Cooking the catch — or anything else — on the shack’s old sheet metal stove was always an adventure. If bumped, as easily happened in the close quarters, the stove had a tendency to collapse and could only be reassembled after cooling down.

More exotic foodstuffs were imported by the revolving cast of shack dwellers, not always with the intended outcome. One night, after leaving a large jar of pickles on the porch, the sleepers were awakened by strange knocking sounds. They found the jar stuck on the head of a staggering and very unhappy skunk — for whom Reid, Frank Woods remembered, expressed droll sympathy as it lurched away in the dark. Doug Dadson recalled a special burnt offering brought by Leney Gage. Impossible to miss, Leney — a six-foot-five blond Adonis, avid stamp collector, and member of the Gage publishing family, arrived for one visit bearing an enormous cooked ham. Even for this crew of hungry young men, it took days to consume. Hung in mosquito netting from the branch of a tree beside the shack (there was, of course, no refrigeration), the ham slowly darkened from pink to a sort of bluish colour, then from blue to black. “We gave up carving the ham by this time,” said Dadson. “It was so rotten we could pick delicious chunks off it till we finally worked our way down to the bone. I’m surprised Jack didn’t become nervous [of ptomaine poisoning], but he didn’t.”8

Occasionally, the young men made sorties by canoe down the Little Joe River to Port Carling on Lake Rosseau, nine miles south, to call on girls they knew at the country club or local cottages. Reid was a strong, skilled canoeist, and calm in trying circumstances, as Frank Woods described one of the Port Carling visits: “We were coming back to Foot’s Bay, just the two of us. It must have been three in the morning and we ran into some terrible winds. I wasn’t the strongest paddler in the world, but Jack was a very fine paddler. I was scared stiff, but he didn’t seem to be worried about it. It was pitch-dark and raining and blowing, but he knew every bend and turn in the river.”9

Woods had been diagnosed with a cardiac weakness following an illness during his final year at UTS, a condition not considered serious but a factor to keep in mind. During their times at Foot’s Bay, Reid always did.

“There was never anything remotely mawkish about Jack,” said Woods, “but he was always very kind and understanding of me. Jack, who never had a physical concern at all — I always appreciated the way he’d nudge me out of the way of the heavy lift or the heavy climb. There was a kindness in him that, frankly, not too many people might have seen.”10

Evenings, the young men often visited their neighbours. Georgia MacKenzie was a warm, welcoming landlady, and the door of Staney Brae was always open for card playing and radio listening. But it was at Cranbrook that they socialized most. Professor Dadson — “Uncle Tom,” as everyone called him — was an endearing character of the crusty, old-school variety. A bachelor, a Baptist, an eminent professor of medieval history, he was in person a short, plump, pipe-puffing gnome with huge shaggy eyebrows, dark, sombre eyes, and a dry sense of humour. When the young men learned that his doctorate at the University of Chicago had been on “Persistent Influence of Paganism in the Thirteenth Century,” he accepted with amused equanimity their referring to his thesis as “Pernicious Influence of Gasoline on the Lifespan of Sparrows.” Both Woods and Dadson roared with laughter as they recalled Uncle Tom’s story of visiting Toronto one winter and being conscripted as a human toboggan on the Avenue Road hill, the long, steep slope south of St. Clair Avenue that was once the north shore of prehistoric Lake Iroquois. Uncle Tom was waiting for a streetcar at the top of the hill the morning after a severe ice storm when an unknown woman lost her footing, fell against him, and clutching him for rescue, launched them on their tandem slide to the bottom. As Uncle Tom told it, once gravity brought them to a stop near the corner of Cottingham Street, a third of a mile south, he, winded and bruised from the crushing descent, addressed the weighty woman now perched atop him: “Excuse me, madame, but you have to get off here. This is as far as I go.”

In some ways a folly with its two-storey central portion, looming quadrangular tower, and offset wings, Cranbrook was a grand summer house with a veranda and a study full of books, easy chairs inside and out, places to write, and when night fell, ample lamplight. Typical were the evenings when Reid and his friends left the shack and made their way through the woods to Uncle Tom’s place for boisterous bouts of bridge and conversation. “It was eight hundred or nine hundred yards away,” said Woods, “but we knew the path so well that we could find our way to and fro on the darkest night without a light.”11

A feature of Cranbrook, usually resorted to on cooler, cloudy days when the bugs weren’t so bad, was the crazy, one-of-a-kind croquet course that Uncle Tom had laid out over several hundred yards of rough, hillocky terrain around his cottage. Because of the broken ground, rotting stumps, juniper bushes, protruding rocks, the hazards of scrub and scree at every turn, hooping the ball and pegging out was really a game of wild and woolly bush golf, a far cry from the genteel ball-tapping on manicured lawns the word croquet normally conjures up. By now a golfer as well as a tennis player, Reid excelled at hacking his way around the course.

That first summer at Miss MacKenzie’s shack established the relationships and pastimes of their Foot’s Bay life that Reid and his friends were to pursue and elaborate over their university years. By the time Reid left for the city in August 1932, plans were already laid to come back the following year. As it turned out, Reid did. But the summer of 1933 would be a momentous one: begun in mourning, ending in love.

Olive Reid had been experiencing bouts of fatigue and malaise unnatural for a woman in her midforties. The diagnosis was endocarditis, an infection that damages heart valves and for which medications and surgical procedures of the 1930s were helpless to correct. By the fall of 1932, the condition was taking its toll. One telling photograph shows Olive standing by herself in her garden appearing wan and tired. There are dark circles under her eyes, a look of sadness and resignation on her face, no trace of the beautiful smile that lights up earlier pictures.

She kept her medical condition to herself. A 1932 Christmas letter written to her Montreal sister-in-law, Grace Reid, wife of Clifford Reid, Harry’s youngest brother, is newsy and lighthearted. Olive declares Christmas “the children’s day” (Grace and Clifford would know — they had five kids to Olive’s one). She mentions the flu season as a reason to be careful. Harry’s nasty head cold is discussed in order to cluck over the impossibility of getting him to stay in and rest up properly. Olive tells Grace that she has taken up interior decorating: “I enjoy it very much and am acquiring a great deal of useful information.” She is about to start an advanced course in January and adds mock-seriously, “so perhaps when you want to do your house over you will require my services.” But worry about her health must have been circulating in the family, for Olive then lightly chides her sister-in-law for spreading rumours:

Olive Reid, 1932, the year before her death.

Grace, who told you I was taking treatments for my nerves? I have taken osteopath treatments for my intestinal trouble. But have not had any trouble with my nerves — so I guess you have been misinformed! I only take an occasional treatment now — in fact, have not had one since August.

Well, I guess this is about all the news for the present. I hope you are all well now, and will continue so through the winter.

Write me again soon. It is too bad we do not hear from each other more often. Love to you all from we three.

— Olive12

Grace Reid preserved the note, pencilling on the corner of its envelope, “Olive’s last letter.”

A danger of endocarditis is that a small clot can break off from a damaged valve and circulate to the brain, causing a stroke. On March 17, 1933 — St. Patrick’s Day — Olive felt unwell. She rested at home. But on Sunday afternoon, two days later, she suddenly lost consciousness while she was lying on the divan in the living room of 79 Humber Trail and died of a cerebral embolism within minutes. That evening, Doug Dadson got a phone call from Reid, who quietly told his friend the news and asked if Doug would come out to the house to keep him company.

Reid’s friends found 79 Humber Trail a much-changed place in the months after Olive’s death, the two men rattling around the house like lost souls, more brothers in their sorrow than father and son. Adding to the gloom were the effects of the Great Depression that Harry Reid faced daily at work. As economic conditions worsened and business dropped, he was forced to cut jobs at Canadian Linotype. Reid saw the impact on his father, who at the end of the day would come home and curl up on the living room couch too bereaved, glum, and exhausted to talk.

“Jack was always a bit mysterious,” said Doug Dadson. “Now he would disappear for a few days. Wouldn’t say where. And you didn’t ask him. Jack never broke down. He was always very controlled. But his mother’s death put him into a strange state for a while. He neglected his studies, drank a bit.”13

The memories of Jack Reid’s early years that Woods and Dadson provided were recorded at Dadson’s Toronto home in March 1983, half a century after Olive’s death and four years after Reid’s own. Dignified gentlemen approaching 70 at the time, Dadson and Woods were by then both retired. Frank Woods, who became a chartered accountant and never married, had ended his career as a vice-president of Moore Corporation, the business forms giant. Doug Dadson, a widower and father of two grown children, was an educator who became the first dean of the Faculty of Education at the University of Toronto. During an interview lasting several hours, Dadson and Woods reminisced about their old friend with warmth and humour, the comments of one prompting amendments by the other. After listening to Doug Dadson’s description of Reid’s rocky, unpredictable behaviour following the death of his mother, Frank Woods quickly added: “But when Jack met Jean and the rest of the Hodge family, he suddenly straightened out again.”14

Frank Woods (left) and Doug Dadson.