2

THE SETTING

The first American exhibition on the Bauhaus was mounted by the Museum of Modern Art in 1938 in a temporary gallery in Rockefeller Center, and it attracted record-breaking crowds—a news photograph shows Frank Lloyd Wright at the opening, chatting with Walter Gropius, who organized the show. What they said to each other is not recorded. The exhibit included photographs, graphics, textiles, furniture, and lighting fixtures produced by teachers and students of the famous German design school. At the entrance was a model of that icon of modernism, the Bauhaus building in Dessau. The large-scale model included details such as balconies and windows, but provided no information about its setting, and gave the impression that the pinwheeling building had been conceived as a huge Constructivist sculpture. In fact, Gropius, who had been formally trained at the Königliche Technische Hochschule in Berlin, designed the building to fit into the Dessau street grid: the long workshop faced the town square, a vertical block anchored the street corner, while the bridge-like administrative wing formed a gateway for the street that led from the train station into the square. In other words, although the Bauhaus building had abstract sculptural qualities, it also responded to its setting. This essential difference is clouded when a building is presented as if it were a freestanding artwork, as it was in the MoMA show.1

Architectural photography also treats buildings as objects. Like a studio portrait, an architectural photograph includes only as much of the background as is needed to flatter its subject; anything offensive—a telephone pole, a stop sign, or an overhead wire—is cropped out. As a result, if your first encounter with a building is on the printed page, seeing the real thing can come as something of a surprise. The first architecture book I owned as a student was Frank Lloyd Wright’s A Testament, a large album with a white cloth cover and the architect’s trademark red square in the top left-hand corner. Wright’s flowery prose didn’t make much of an impression, but I admired his work, particularly the Robie House, a photograph of whose long brick façade stretched over two pages. When I finally had the opportunity to see the building, I was disappointed to discover that this “prairie house” was actually in Hyde Park, an urban neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side. The house was on a shallow lot, very close to the sidewalk, with a walled service yard and virtually no garden, and it was surrounded by neighboring houses and apartment buildings, instead of by a natural landscape as in Richard Nickel’s lyrical photograph.

FITTING IN

Paintings and sculptures can be autonomous works of art, but architecture is always part of a particular place. It is difficult to fully appreciate Kahn’s design for the Yale Center for British Art, for example, without knowing that it stands across the street from the Yale University Art Gallery, a 1920s Gothic Revival building by Egerton Swartwout that includes a 1950s addition by Kahn himself. The Yale Center plays off Swartwout’s richly ornamented stone façade, and is a metallic counterpart to the blank brick wall of Kahn’s addition. Another important piece of information: Chapel Street forms a town/gown boundary, with the Yale campus on one side, and New Haven on the other. The center is part of the latter, which may explain why Kahn made the exterior so low-key (the ground floor contains shops). Or maybe he just chose to play David to Paul Rudolph’s nearby Yale School of Architecture Goliath.

The setting that presented itself to Kahn consists of thoughtfully designed college buildings on an orderly street animated by the bustle of university life. This is very different from the surroundings facing Frank Gehry when he was making his reputation as an architectural maverick in the 1980s in Los Angeles. His residential commissions were small houses on cramped lots in Venice Beach, not villas in Bel Air. His settings were a scruffy mixture of popular styles, garish colors, and humdrum materials, hardly the ideal backdrop for conventional modernist buildings. But Gehry was an unconventional modernist. He saw what the leading American architects, mostly Easterners—Richard Meier, Michael Graves, Peter Eisenman—were doing and he was intent on going his own way. His surprising, but in hindsight perfectly sensible, response to his surroundings was to join the party. “Anything you put in Venice is absorbed in about thirty seconds,” he said. “Nothing separates itself from that context. There’s so much going on—so much chaos.” Instead of elegant refinement and pristine design, Gehry’s early projects explore rough materials, vivid colors, and unruly forms. A beach house has a pergola made out of what appear to be pieces of a telephone pole; a family house in the San Fernando Valley is finished in tar-paper shingles; a twin house in Venice has sections of exposed wood framing and walls of galvanized corrugated metal and unpainted plywood. This was a matter of limited budgets, but it was also a way for Gehry to deal with the brassy environment of Los Angeles.

Frank O. Gehry & Associates, Chiat\Day Advertising, Venice, California, 1991

Even when the commissions were larger, such as a three-story office building for the Chiat\Day advertising agency, the setting—Venice’s Main Street—was a raucous mix of strip malls, garden apartments, and parking lots. Gehry responded to the small scale of the street by breaking his building into two parts, one almost banal, the other striking, with a projecting roof supported by a cluster of angled, copper-clad braces. The most unusual feature of the building came about by accident. As Gehry told the story, he was discussing a model of the project with his client, who said he wanted an art component in the building. Two years earlier, Gehry had worked with Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen on a tower in the form of a giant pair of binoculars, and he still had the maquette on his desk. “I pushed it in front of the central shape as I was describing to Jay Chiat the sculptural qualities the center needed,” Gehry said. “It worked.”

Surroundings can also be an inspiration instead of a constraint. Alvar Aalto’s Villa Mairea is one of several residences in a compound belonging to a prominent industrialist family, located in a dense pine forest in western Finland. The setting moved the architect to use wooden poles throughout the house. Poles support the entrance canopy, surround the staircase, and are used as balcony railings—at a time when modernist railings were always made out of steel pipes. Even the structural columns in the living room recall tree trunks in a forest. Rather than set the house in opposition to its natural setting, as Mies did with the Farnsworth House, Aalto used the surroundings to inform his architecture.

Another building that finds inspiration in its setting is the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, designed by Moshe Safdie. The site, a spit of land overlooking the Ottawa River, is dominated by nearby Parliament Hill and the federal parliament complex, a mid-nineteenth-century collection of Victorian High Gothic buildings with animated roofs, towers, and spires. The most striking structure on Parliament Hill that is visible from the National Gallery is the polygonal parliamentary library, which is modeled on a medieval chapter house, complete with flying buttresses, spiky finials, and a conical roof. Responding to this view, Safdie created a modern counterpart to the library, a tall, pinnacled steel-and-glass pavilion housing a combination lobby and gala space. This daring architectural gesture works on several levels. It provides a memorable image for the large, sprawling museum. It adds to the skyline of downtown Ottawa, which includes the parliament buildings, the nearby spires of Notre-Dame Basilica, the picturesque roofscape of the Château Laurier hotel, and the tall copper roof of Ernest Cormier’s Supreme Court. Most important, it provides a visual link between two national institutions, one political, the other cultural.

Moshe Safdie & Associates, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 1988

The surroundings of the proposed African American museum in Washington, D.C., include no obvious architectural touchstone, for while the national capital is often characterized as a white classical city, the museums that line the National Mall are a remarkably motley group. There are several classical buildings: the somewhat pompous Museum of Natural History, the ponderous Department of Agriculture, John Russell Pope’s magnificent National Gallery, and Charles Adams Platt’s graceful Freer Gallery. On the other hand, James Renwick Jr.’s red-sandstone Smithsonian Castle is Gothic Revival, and Adolf Cluss’s eccentric polychrome brick Arts and Industries Building defies easy classification. The modern buildings are no less varied: Pei’s minimalist East Building stands opposite Cardinal’s Gaudiesque American Indian museum; Bunshaft’s drumlike Hirshhorn is next to the generic glass boxes of Obata’s Air and Space Museum, and the neighbor of the future African American museum is the Museum of American History, one of the last projects of the venerable McKim, Mead & White firm, trying to be modern and not succeeding very well.

How did the architects in the competition for the African American museum deal with this variety? Antoine Predock obviously decided that the architectural potpourri gave him license to add his own voice to the mix, so did Diller Scofidio + Renfro. Norman Foster opted for a distinctive circular form, echoing the Hirshhorn. Moshe Safdie and Henry Cobb related the general mass of their buildings to the boxy Museum of American History. David Adjaye described his design as a “hinge” between the informal grounds of the Washington Monument and the formal Mall landscape. He responded to his immediate surroundings by designing a square monumental form; at the same time he ensured a distinctive presence by making the corona bronze rather than marble or limestone. He also did something rather cunning; the angle of the beveled corona matches the angle of the capstone of the Washington Monument, establishing what architects call a “conversation” between the two structures.

* * *

Few buildings are as difficult to insert into an urban setting as a concert hall. Unlike a museum, which is a collection of rooms of various sizes that can be arranged in different ways, the shape of a concert hall is dictated by acoustics, sight lines, and, in the case of an opera house, extensive backstage facilities. Nevertheless, the architect must fit what is essentially a very large windowless box into its surroundings.

Gehry’s 1988 competition-winning design for the Walt Disney Concert Hall created a memorable image of the building, which stood in a relatively nondescript part of downtown Los Angeles, by breaking down the hall into a series of giant alcove-like rooms focused on the orchestra. This neatly solved the problem of the exterior by creating an irregular form. At this point in his career, Gehry tended to design buildings that looked like jumbled collections of disparate volumes, and Disney Hall was no exception: the auditorium stood next to a domed greenhouse-like lobby and several smaller shapes. While the competition unfolded, the orchestra’s building committee toured the world’s leading concert halls. The committee, and the conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen, were particularly taken by Tokyo’s Suntory Hall and its vineyard style of seating in which the audience occupies “terraces” that surround the orchestra. The acoustician who had worked on Suntory, Yasuhisa Toyota, was invited to join the Disney team. Gehry set aside his competition design and, working with Toyota, started over from scratch. They concluded that, for acoustical reasons, a vineyard-style hall should reside in a concrete box approximately 130 by 200 feet, with angled walls and roof. To soften the external visual impact of the ten-story-tall volume, Gehry wrapped it with sail-like shapes. Wrapping the building camouflaged the auditorium, and the space between the wrapping and the box accommodated the lobby, a café, an informal performance space, and outdoor terraces. The loose wrapping also left space for skylights, bringing natural light into the lobby as well as into the hall itself. The architect’s early sketches show the wrapping as a flurry of wavy lines, lending credence to the story that he designed the hall by crumpling a piece of paper.2 “That’s mythology. I wish I could do that, but it’s not true,” he told an interviewer. “If only it were that easy. The Disney Hall was never a crumpled piece of paper. The fact is I’m an opportunist. I’ll take materials around me, materials on my table, and work with them as I’m searching for an idea that works.” Sometimes the opportunism backfires. The Experience Music Project museum in Seattle, which opened in 2000, is a motley collection of multicolored forms that are said by Gehry to have been inspired by the bodies of Stratocaster guitars. But when I saw the building twelve years later, the crowd streaming to visit the neighboring Space Needle hardly gave the idiosyncratic museum a second glance.

One of the stated purposes of Disney Hall was to galvanize the long-awaited development of downtown Los Angeles. Toronto already has a thriving downtown with dynamic street life, cultural institutions, and a large residential population. Thus, the challenge for the local architect Jack Diamond in designing a new ballet-opera house was to make sure that the building fit happily into the surrounding city rather than to create an urban magnet or a tourist attraction. Completed in 2006, the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts occupies a full city block on University Avenue, the city’s most prestigious thoroughfare. Diamond’s design is basically a collection of boxes: the largest box contains the auditorium, a tall box houses the fly tower; lower boxes accommodate backstage functions; and a glazed box overlooking University Avenue contains the lobby. The interior of the building is warm: light-colored wood, Venetian plaster, ocher-colored tones. The auditorium has been highly praised for its acoustics, its excellent sight lines, and its intimacy—three-quarters of the two thousand seats are within a hundred feet of the stage.

Gehry Partners, Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, 2003

Diamond Schmitt, Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts, Toronto, 2006

Diamond studied under Louis Kahn, and while his style is different, he shares Kahn’s belief that architectural form is the result of analyzing a building’s essence. “You arrive at the sublime or poetic not by metaphor,” Diamond has said, “but by making virtues out of necessity. That’s the secret of design.” The necessities of the Four Seasons Centre included a cramped site, the stringent requirements of the hall, and a restricted budget.3 The building was designed from the inside out, just like Disney Hall, but Diamond wrapped the opera house in a distinctly less glamorous material than stainless steel: dark, chocolate-colored brick. Only the large front façade that looks out on University Avenue is glass.

“A touch of the spectacular on all four sides of the centre would have gone a long way to argue the noble cause of culture,” wrote one dissatisfied Toronto critic. Another complained of the building’s “earnest stolidity.” The Toronto Star went further, listing the Four Seasons Centre as “the fifth-worst building in Toronto.” The reason for this dissatisfaction was the recent construction of several prominent new buildings in the city: an in-your-face university student residence by Thom Mayne, an art school raised on angled stilts by the British architect Will Alsop, and Daniel Libeskind’s lopsided addition to the Royal Ontario Museum. By the inflated standard of these self-conscious signature buildings, the understated architecture of the Four Seasons Centre was a definite letdown.

The Toronto critics carped, but Valery Gergiev, artistic director of the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, saw understatement as a good thing. Two successive high-profile international architectural competitions for a new opera house for his theater had produced no satisfactory result. The first competition had been won by the Los Angeles firebrand Eric Owen Moss, whose radical design resembled an iceberg. Moss’s project, as well as his revision, were rejected by the Russian government (which was footing the bill), and a second competition was held, this one won by Dominique Perrault, architect of the ill-starred Bibliothèque Nationale. The Frenchman enclosed the opera house in a multifaceted dome of gold-tinted glass. Gergiev called the design “very flamboyant, very fractured and not easy to build”—St. Petersburgers called it “the golden potato.” Costs spiraled, technical problems multiplied, and Perrault was fired. During a North American tour, Gergiev visited Toronto’s Four Seasons Centre. He was struck, as he put it, “by its beauty, its practicality and friendliness with neighboring buildings, its superb acoustics,” and he invited Diamond’s firm, Diamond Schmitt, to St. Petersburg. A third competition followed, which the Canadians won.

The construction site of what is called Mariinsky II fills a city block across a canal from the original nineteenth-century Mariinsky Theater, designed by Alberto Cavos, a Russian architect of Italian descent. Italian and French architects had built the new city for Peter the Great in the eighteenth century, and over the years the center of St. Petersburg, then the capital, developed into a remarkably coherent architectural ensemble, a northern version of Venice. The Russian city is distinguished by canals and beautiful architecture in a variety of styles: colorful Baroque, sturdy neoclassical, delicate Empire, and romantic nineteenth-century eclecticism. The difficult but unavoidable question for an architect is how to add a new building to such surroundings: Should it stick out, fit in, or be something in between?

Moss and Perrault had opted to stick out. Their glassy designs were to be light beacons during the long, dark Russian winters, but they were also intended, in every way possible, to contrast with their surroundings—in material, form, and relation to the street. This worked for Gehry in Los Angeles but it seems wrong for St. Petersburg, a city where architects have been building for several hundred years, not necessarily in a consistent style, but in a manner that produced consistent results. Modernist architects argue that new architecture should contrast with old, although that is often merely an excuse for artistic license. That, at least, is how it seemed to many people in St. Petersburg, where public opposition to “sticking out” accounted, in part, for the government’s decision to abandon the two earlier projects.

Diamond Schmitt, Mariinsky II, St. Petersburg, 2013

Diamond took the middle road. He had experience building in historic cities, having designed a new city hall for Jerusalem, near the Jaffa Gate, a modern building that successfully fits into its ancient surroundings. His concept for the Mariinsky opera house, unlike Perrault’s glass crystal, is exceedingly simple—a box housing a traditional horseshoe-shaped hall. Cities, as Diamond often points out, are composed of boxes. The St. Petersburg box—stone rather than brick, as in Toronto—is intended to harmonize with the surrounding nineteenth-century buildings, although the style of the architecture is modernist, with simple details and large expanses of glass. The opera house, which opened in 2013, also adds to the St. Petersburg skyline with a dramatic roof form and a roof terrace with curving glass canopies.

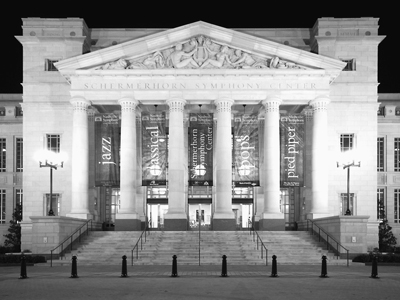

David M. Schwarz Architectural Services, Schermerhorn Symphony Hall, Nashville, 2006

All good concert halls are designed from the inside out. In a book written before Walt Disney Hall and the Four Seasons Centre were built, the eminent acoustician Leo Beranek ranked the world’s best concert halls—seventy-six of them—according to a survey of conductors, musicians, and music critics. The top tier included only three halls: the Grosser Musikvereinssaal in Vienna, the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, and Symphony Hall in Boston. All three, built in the late nineteenth century, are so-called shoeboxes: long, rectangular rooms with high ceilings and wraparound balconies. When the architect David M. Schwarz was commissioned to design a new concert hall for the Nashville Symphony Orchestra, he took the Musikvereinssaal as a model, added a balcony to increase the seating capacity, but preserved one of the old hall’s attractive features, high windows in the two long sides.

The interior of Nashville’s Schermerhorn Symphony Hall has less gilt than the Musikvereinssaal but it is designed in a similar neoclassical style. On the exterior, the entrance is identified by a portico in the shape of an ancient temple, although the Corinthian columns appear more Egyptian than Greek. The statues in the pediment of the temple front, sculpted by Raymond Kaskey, represent the musician Orpheus and his wife, Eurydice. Bernard Holland, the music critic of The New York Times, objected to the ancient symbolism, and found the building too tame. “It doesn’t argue with the neighbors,” he complained. “Originality, it has been decided, is not only bad policy but bad manners.” But getting on with the neighbors is the whole point. Nashville has been long known as the “Athens of the South,” and its downtown has many Greek Revival buildings, notably William Strickland’s nineteenth-century Tennessee State Capitol, a 1920s replica of the Parthenon, McKim Mead & White’s War Memorial Auditorium, and Robert A. M. Stern’s recent Public Library. So Schwarz was merely adding another chapter to what was already a long classical story.

William Rawn Associates, Seiji Ozawa Hall, Tanglewood, 1994

Seiji Ozawa Hall in Tanglewood is another shoebox. Unlike most concert halls, the summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in the Berkshires is in a rural setting, so how did the architect William Rawn design a largely windowless boxy structure in a grassy field? His solution was to give the box an industrial character, with heavy brick walls and a vaulted metal roof, which vaguely recall a New England textile mill. The somewhat stern effect is softened by barnlike wooden porches, and the hall fits very well into its bucolic surroundings. The interior is wood. In an updated version of his earlier study, Leo Beranek ranked Ozawa Hall the fourth-best American hall, after Boston’s Symphony Hall, Carnegie Hall, and the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center in Dallas, designed by I. M. Pei.

Of course, concert halls are about more than acoustics, sight lines, and fitting a building into its setting. The German architect Erich Mendelsohn once wrote that architects are remembered best for their one-room buildings. In a one-room building like the Pantheon, you are immediately there, at its heart, in its reason for being. Opera houses and concert halls have an added dimension: they are also places of public assembly. They encompass a shared experience and, like cathedrals, they are places whose architecture contributes to that experience. Once the curtain goes up, the hall belongs to the performers, but until then the architect is free to pull out all the stops.

ADDING ON

At thirty-six, Edwin Lutyens was already an experienced architect, having been in practice for sixteen years, and thanks to his talent, his satisfied clients, and the support of Country Life magazine, he had become the most fashionable country-house architect in Britain.4 In 1905, he was commissioned to enlarge a seventeenth-century farmhouse at Folly Farm in Sulhamstead, Berkshire. He added a two-story hall, and a kitchen wing in the rear, and created a perfectly symmetrical garden façade. The new house combined delicate Queen Anne with simple Arts and Crafts details—silver-gray brick and red-brick trim—a style that Lutyens jokingly called “Wrennaissance.” The pride of Folly Farm was an extraordinary garden, laid out by Gertrude Jeckyll, Lutyens’s longtime collaborator and friend.

In 1912, Folly Farm was bought by Zachary Merton, an elderly industrialist whose new German bride was a friend of Lutyens’s wife. The Mertons commissioned Lutyens to enlarge the house—they wanted a grander dining room, more bedrooms, and a larger kitchen. Even though the addition would more than double the size of the house, Lutyens chose neither to harmonize with his original design nor to upset its symmetry with an overpowering extension. Instead, he reverted to the style of his earliest houses, which had been based on English rural architecture. The new red-brick addition, which he called a “cowshed,” has an immense tiled roof that almost touches the ground, massive chimneys, and heavy brick buttresses that form a cloister beside a shallow fishpond that Lutyens referred to as a “water tank.” The overall effect is to make the original graceful house appear to be a later addition to a medieval barn, rather than the other way around.

The story of Folly Farm underlines another way in which architecture differs from the other arts—buildings are never really finished; new owners have new functional requirements, technology evolves, fashions change, life intervenes. In the past, the construction of a large building such as a cathedral or a palazzo could take many decades and it was assumed that the design would be modified by successive architects. King’s College Chapel, for example, which was begun in 1446, was completed, three monarchs, one War of the Roses, and seventy years later. The work is generally attributed to four master masons, while an independent team of Flemish craftsmen is credited with the stained-glass windows. By the time that an oak rood screen was added to the chapel—in 1536—Gothic was out of fashion and the design of the celebrated screen is an example of early Renaissance classicism. Each builder observed the precedent set by the previous generation, but followed no strict predetermined plan.

Modern buildings take less time to construct, but they, too, are subject to change. When Fallingwater was completed, it must have seemed perfect, a finished work of art. Yet only three years after it was designed, with more visitors coming to the increasingly celebrated house, the Kaufmanns asked Wright to add a guesthouse, rooms for more servants, and a four-car carport. Wright, of course, obliged. He did not hide the uphill addition, which is linked to the main house by a striking curved canopy that steps down the slope.

Architects are rarely given the opportunity to enlarge a building more than once. In the late 1950s, a pair of young Danish architects, Vilhelm Wohlert and Jørgen Bo, were approached by Knud W. Jensen, a wealthy art collector who wanted to convert a nineteenth-century country house into a private museum. The site was a twenty-five-acre estate named Louisiana, overlooking the Øresund strait, just north of Copenhagen. Wohlert and Bo renovated the old house and added two freestanding galleries, which were connected to the house—and each other—by glazed corridors. The new wood-and-brick buildings were low-key, unpretentious, human in scale, and designed in the style that became known as Danish Modern. Jensen’s collection grew, and his museum expanded accordingly. On four separate occasions during the next thirty-three years, the architects added more galleries, a small concert hall, a café, a children’s wing, a museum shop, and a sculpture court. As a result, the Louisiana Museum has an unusual layout: a loose circle of connected pavilions in a spacious old park beside the sea. While the architects’ style developed over the years, they stayed true to their understated modernist roots, and their remarkably consistent meandering architecture has produced a much-admired museum.

Consistency was not one of Philip Johnson’s virtues. In 1961, he was commissioned to design a memorial to Amon G. Carter, a Fort Worth, Texas, newspaper publisher. The building, located in a park, took the form of a small art gallery housing Carter’s collection of Frederic Remingtons, and resembled a little temple with a portico supported by delicate arches of smooth Texas shellstone. This was Johnson’s first building in a style that one critic called “ballet classicism,” referring to the tapered columns that resembled a dancer en pointe. The Carter Museum was hardly more than a garden pavilion, and two years later Johnson was called back to add a discreet addition in the rear. Fourteen years after that, the museum undertook a major expansion, and Johnson, who was no longer interested in classicism, added a large wing in a heavy geometrical style. The result was hardly as felicitous as Folly Farm, however, and in 2009, when the museum needed to expand a third time, Johnson demolished both earlier additions and replaced them with a two-story granite-faced block that forms a sedate backdrop to his perfect little jewel box of a pavilion.

Vilhelm Wohlert & Jørgen Bo, Louisiana Museum of Art, Humlebæk, 1958–91

Philip Johnson, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, 1961

Neither Johnson nor Wohlert and Bo anticipated expansion, but buildings are sometimes designed with future growth in mind. When the Philadelphia architect Frank Furness designed the main library of the University of Pennsylvania at the end of the nineteenth century, he made it a “head-and-tail” building: the head housed a soaring reading room, while the iron-and-glass tail contained the book stacks. The stacks, which held a hundred thousand books, were designed to expand, bay by bay, from three bays to nine. But in 1915, the university thoughtlessly erected a building next to the library, effectively blocking any future expansion. Furness had died a few years earlier, so he had no say in the matter.

Furness’s story is not unusual. A building may be designed to grow, but by the time that the need to expand occurs, several decades have passed and the original architect’s intentions are often forgotten, or merely ignored. Moreover, it is likely that the new architect has his own ideas. That is what happened at Scarborough College, a suburban satellite of the University of Toronto, built in the early 1960s. The Australian architect John Andrews designed the entire campus as a linear concrete building, a so-called megastructure. Scarborough College was considered a cutting-edge design and a harbinger of the future; however, as the campus grew, later architects ignored Andrews’s restrictive linear model. Instead, a library, student center, athletic facilities, and a school of management were each housed in separate freestanding buildings. Another Brutalist megastructure campus of the 1960s, this one in Britain, suffered a similar fate. Denys Lasdun designed the campus for the new University of East Anglia in Norwich as a linear megastructure incorporating raised pedestrian decks. Within a decade, the raised-deck concept was set aside, and soon even the contrived forty-five-degree diagonal geometry of the original plan was ignored. The first architect to detach himself from Lasdun’s megastructure was Norman Foster when he built the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts. Fourteen years later, he was called back to extend the building. He knew exactly how to do it, since his linear plan could be extended at either end. However, his clients wanted the original building to remain unaltered. Accordingly, Foster designed an underground addition that left the shed intact.

No one can add to a Foster-designed building as confidently as Norman Foster, but at some future time, fifty years hence, say, the Sainsbury Centre may need to grow again, and some architect will have to decide how. In that case, he or she will have several options. Underground extensions are one alternative; another is to extend a building in the same way you lengthen a skirt or a pair of trousers—seamlessly. When Eero Saarinen planned Washington’s Dulles International Airport in the early 1960s, he designed a building that could be extended at either end. Thirty-three years later, the airport needed to grow to accommodate more traffic, just as he had anticipated. The architect, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, doubled the length of the terminal, replicating the original scheme of a draped concrete roof supported by catenary cables tensioned by outward-slanting piers. The building today looks much as before, except that instead of fifteen bays, there are now thirty.

When Romaldo Giurgola was commissioned to expand the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, he chose seamlessness. His longtime colleague and friend Louis Kahn had completed the building seventeen years earlier, but he was no longer alive. The museum consists of a series of parallel vaults, which Giurgola proposed to simply extend, increasing the building’s length from three hundred to five hundred feet. His rationale was that Kahn had originally designed a longer building, but had been obliged to build a shorter version for budgetary reasons. However, most admirers of Kahn considered his building to be inviolable, and there was an international outcry. “Why ruin the masterwork of Kahn’s life with such an ill-considered extension?” asked a letter to The New York Times. “To put it bluntly, we find this addition to be a mimicry of the most simple-minded character.” The signatories included Philip Johnson, Richard Meier, Frank Gehry, and James Stirling. The museum balked, and Giurgola’s reasonable attempt to add to a famous building by imitating its architecture was shelved.

One man’s mimicry is another man’s respect. In 2006, Allan Greenberg was commissioned to design an addition to Princeton’s Aaron Burr Hall, a late work by one of America’s most distinguished nineteenth-century architects, Richard Morris Hunt. Hunt built extravagant mansions in Newport, Rhode Island, as well as the Metropolitan Museum in New York and Biltmore House in North Carolina, but at Princeton he kept his usual flamboyance in check, perhaps because this was a workaday laboratory. He designed a straightforward brick box with carefully proportioned windows trimmed in sandstone; the only whimsical touches are a battered-stone base and crenellated battlements at the roofline. Greenberg dispensed with the battlements in his addition, but maintained the sturdy, almost military bearing of the building, matching the red Haverstraw brick, red mortar, Trenton sandstone trim, and battered-stone base. He carefully lined up the windows, cornice lines, and rooftop parapets with the original. At the same time he did not slavishly imitate his predecessor, and introduced contrasting bands of sandstone. He turned one corner with an octagonal tower containing a staircase, and added two decorative touches: rosettes with a bull’s-eye pattern, and a discreet plaque with the university crest. In all, he managed to tease something original—albeit quite modest—out of Hunt’s vocabulary. The addition, against all odds, is neither a pastiche nor a facsimile. It is more like a dialogue between two architects across the years.

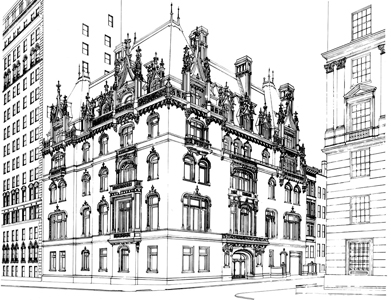

Kevin Roche was even more circumspect at the Jewish Museum on New York’s Fifth Avenue. The museum is housed in the former Warburg Mansion, designed in 1908 by Charles P. H. Gilbert in the French Renaissance style. The museum moved into the mansion in 1947, and in 1963 added a bland annex on the Fifth Avenue side. In 1993, Roche was commissioned to further expand the building. He had been Saarinen’s right-hand man and with John Dinkeloo had taken over the practice after Saarinen’s death, and designed such modernist landmarks as the Oakland Museum of California and the Ford Foundation headquarters building. Roche might have been expected to design a contrasting addition to the Jewish Museum; instead, he hid the 1963 annex behind a new French Renaissance façade of Indiana limestone with pinnacled dormers and a mansard roof. The exquisitely detailed addition extends Gilbert’s architecture in such a way that it is impossible to tell where the latter stops and the former begins. Instead of a conversation it is more like a séance—Roche channeling Gilbert from the grave.

Allan Greenberg Architect, Aaron Burr Hall, Princeton University, 2005

Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo & Associates, Jewish Museum, New York, 1993

Herbert Muschamp, the architecture critic of The New York Times, acknowledged that the new addition to the Jewish Museum respected the old architecture—which he mislabeled as “Gothic”—but he was uncomfortable with the contemporary use of a period style. “Though the expansion means to honor history, it ends up sacrificing history to taste,” he wrote. “Mr. Roche has enlarged a chateau but not our view of its place in time.” It is unclear how a different addition would have enlarged our view of the mansion’s “place in time,” but evidently Muschamp preferred the more conventional practice of contrasting the new with the old.

Contrast was the theme of the glass atrium designed by Bartholomew Voorsanger and Edward Mills in 1991 for the Morgan Library in New York. The original library, designed in 1906 by Charles Follen McKim, is a severe marble box, modeled on Baldassare Peruzzi’s sixteenth-century Palazzo Pietro Massimi in Rome. There are only four rooms in the Morgan Library: two large chambers flanking a domed entrance hall, and a small office. The building shared the block with J. P. Morgan’s pre–Civil War family mansion and a 1928 annex built by his son; Voorsanger & Mills’s atrium linked all three. I recall eating in the atrium café and thinking that the curved glass roof was more suitable for a discotheque. Instead of a contrast, a clash.

When Renzo Piano was commissioned to extend the Morgan in 2006, he demolished the offensive addition and replaced it with a tall all-glass lobby, a handsome and exceptionally well-built space, so cool as to be almost diffident, carefully allowing McKim’s palazzo to remain the star. The only loss in the new building—and it is a major one—is that the entrance to McKim’s library is no longer the front door on Thirty-Sixth Street. Instead, one slinks ingloriously into the palazzo through an improvised corner entrance at the rear.

Piano is a master of the contrasting addition—he has to be, since it is impossible to blend his light, precisely detailed steel-and-glass architecture with older masonry buildings. His work is in evidence at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, and he is designing a steel-and-glass pavilion for the Kimbell Art Museum, which is intended to contrast with Kahn’s concrete-and-travertine building. It remains to be seen if this proves a superior solution to Giurgola’s aborted extension.

Richard Rogers, too, is a master of contrast, as he demonstrates in 300 New Jersey Avenue, an addition to an office building in Washington, D.C. The older building, originally the headquarters of the venerable Acacia Life Insurance Company, was designed in 1935 by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, the architects of the Empire State Building. Like the Empire State, the six-story Acacia Building is an example of early American modernism: a blend of Beaux-Arts planning, practical engineering, and an Art Deco sensibility. Rogers demolished a parking garage on the north edge of the site, replacing it with a new ten-story office wing, and turned the triangular courtyard between the new and old buildings into a roofed atrium. A similar strategy to Piano’s at the Morgan, but executed in a very different way. A jungle-gym tower stands in the center of the atrium. The tower contains glass elevators and supports the atrium roof, which looks like a giant glass umbrella. Glass-floored footbridges connect the tower to the new and old buildings. Precision is a hallmark of Rogers’s architecture, but here precision is accompanied by a kind of rough-and-ready brashness that recalls the heroic architectural modernism of the 1920s. Painted steel, bare concrete, structural struts, and exposed plumbing are blended into one kinetic whole.

Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, 300 New Jersey Avenue, Washington, D.C., 2010

Such structural high jinks are light-years away from Shreve, Lamb & Harmon’s orderly design. “That was then, this is now” is Rogers’s message. Contrasting new and old is an architectural cliché that often leaves the old in its dust, but that’s not the case here. One comes away admiring both buildings. Much has changed in seventy-five years, except the sense of conviction that is the accomplished architect’s hallmark.

Rogers was a runner-up in a 1982 competition for an extension to the National Gallery in London. The unbuilt winning scheme, by Ahrends Burton & Koralek, occasioned the famous remark by Prince Charles, who described it as a “monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend,” and set off a firestorm of public debate about modern architecture. The result was a new competition, with six firms being invited to submit designs. The contestants were instructed that while the new wing should be “a building of outstanding architectural distinction,” it should also fit into the setting of Trafalgar Square, and be a sympathetic neighbor to William Wilkins’s neo-Grecian National Gallery, which, while not a great work of architecture, is an important feature of the Trafalgar Square setting.

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown’s winning scheme is an unusual combination of knowing seamlessness and gentle—and not-so-gentle—contrast; sometimes a reflection of its surroundings, sometimes a counterpoint to them. The façade on the square begins with what Venturi called a “crescendo of columns,” an exact copy of Wilkins’s giant Corinthian pilasters, blank attic windows, dentilated cornice, and rooftop balustrade. In Venturi’s hands, these classical elements seem to fade—literally—into the new façade, until they disappear altogether. In contrast to this scenographic tour-de-force, the rest of the building contains no architectural allusions to the old building, except for maintaining the same roofline and using the same Portland stone. A single giant fluted Corinthian column stands at the corner, and seems to have wandered over from the gallery’s portico. Or is it a reference to Nelson’s Column in the square?

The critic Paul Goldberger observed about Venturi’s design that “this is the late twentieth century trying not so much to abandon classicism as to make its own comment on it.” Throughout, the new building alternates between respecting the architecture of its older neighbor and reminding us that it is, indeed, a modern building. The new wing is pulled away from the National Gallery, leaving a pedestrian passage and a glimpse of the interior grand staircase, visible through a steel-and-glass curtain wall that is harshly juxtaposed with the old building. The entrance to the new wing is through an aperture that appears to have been cut out of the façade with a sharp knife—Venturi has said that the size of the opening is based on the dimensions of a London double-decker bus. The rear wall of the wing is blank except for two large ventilating grilles and the name of the building carved into the stone in six-foot-high letters. Venturi explained how the setting influenced the design. “Each of the four façades is different—involving the Miesian glass curtain wall to the east, the severe brick-faced ‘back’ walls to the north and west, and the limestone façade to the south.” He referred to the limestone façade as a “mannerist billboard.”

Venturi, Scott Brown & Associates, Sainsbury Wing, National Gallery, London, 1991

Venturi, perhaps more than any architect of his generation, consciously founded his architecture on a theory. Most architectural ideas emerge from an architect’s confrontation with a particular program, site, or client, and are refined in subsequent projects; Venturi’s theory was presented first in a book. “In the medium of architecture, if you can’t do it, you have to write about it,” he observed, describing the situation of a neophyte exploring as-yet-unrealized architectural ideas through the medium of the written word. His 1966 manifesto, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, was a reaction to what Venturi considered the oversimplified sculptural and monumental forms of orthodox modernist architecture. He used historical examples to illustrate his thesis that great architecture had frequently been inconsistent, complex, and contradictory. In a later book, Architecture as Signs and Systems, written with Denise Scott Brown, he examined how buildings could communicate specific messages through iconographic decoration rather than through their form. This is what drove the design of the extension to the National Gallery.

The front façade as sign is independent of the other three façades of the wing, as it acknowledges its context: the original historical building, which it is a continuation of, and Trafalgar Square, which it faces.

This façade as billboard relates to the façade of the original building through analogy and contrast—that is, its Classical elements are exact replications of those of the original façade, but their positions relative to one another vary significantly to create compositional inflection of the new façade toward the old façade, while at the same time maintaining a unified monumental face toward the grand square.

Do we really need the architect’s explanation to appreciate a building? The complicated visual games that architects such as Venturi play often leave the viewer in a swamp of literary and historical allusions; I doubt that the casual passerby really perceives the façade of the Sainsbury Wing as a “billboard.” If Venturi were a purely cerebral theoretician, his architecture would be stillborn, but he isn’t and it isn’t. Twenty years have passed since the Sainsbury Wing was built, and the weathered and stained Portland stone of the new building blends nicely with the old. The “crescendo of columns” is much less conspicuous than when the stone was new, and now appears merely amiably eccentric. From Trafalgar Square, the wing looks exactly right, a small addition to a large building, quietly asserting itself in quixotic and sometimes cheeky ways, but paying close attention to its larger neighbor.