4

PLAN

One of Le Corbusier’s frequently quoted maxims is “The plan is the generator.” What does that mean? In his Swiss Calvinist way, Le Corbusier saw planning as nothing less than the basis of civilization. “Without plan we have the sensation, so insupportable to man, of shapelessness, of poverty, of disorder, of willfulness,” he wrote in his 1923 manifesto, Towards a New Architecture.

The eye observes, in a large interior, the multiple surfaces of walls and vaults; the cupolas determine the large spaces; the vaults display their own surfaces; the pillars and the walls adjust themselves in accordance with comprehensible reason. The whole structure rises from its base and is developed in accordance with a rule which is written on the ground in the plan.

He included drawings of ancient buildings—the Temple at Thebes, the Acropolis, Hagia Sophia in Istanbul—to demonstrate how a three-dimensional form is the vertical projection of a floor plan, and that the plan is a timeless feature of architecture, irrespective of culture or epoch. He underlined its continued relevance by including his own plans for a so-called Radiant City, a city of geometrically laid-out towers.

Le Corbusier suggested that in designing a building, the most important thing was to decide on the plan—the rest would follow. Like many early modern architects, he had no formal training; nevertheless, his emphasis on planning followed accepted École des Beaux-Arts practice.1 The École stressed three-dimensional design as well as details, but it was the plan that was considered the key to a good building. “You can put forty good façades on a good plan,” Victor Laloux, a famous teacher, advised his students, “but without a good plan you can’t have a good façade.”

A Beaux-Arts drawing is a beautiful thing. I have a French friend whose grandfather, Léopold Bévière, attended the École in the 1880s, its glory days, and was accepted into the Atelier André, where Laloux had earlier studied. Several of his grandfather’s student drawings hung in my friend’s dining room, immense watercolor renderings showing in delicate detail a Class A (or final) project. I think it was a spa. I still have my first student watercolor rendering—a sculptors’ camp in a forest—but it is a crude, coarse effort compared with these exquisite creations.

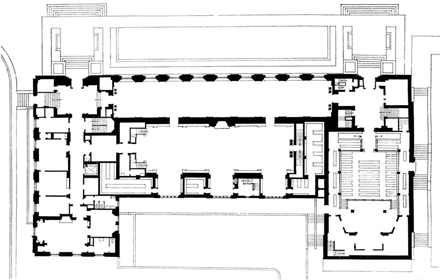

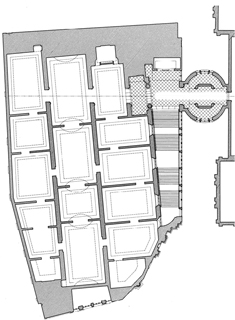

A Beaux-Arts plan may look like an exercise in accomplished draftsmanship, but its composition reflects careful study of the way that a building actually functions. In the late 1920s, Henry Clay Folger commissioned the French-born Philadelphia architect Paul Philippe Cret, a distinguished ancien élève, to design a building to house his remarkable collection of Shakespeareana. The prominent site in Washington, D.C., was on Capitol Hill, behind the Library of Congress. Cret had to accommodate a reading room, an exhibition gallery, and a lecture theater, as well as administrative offices. The theater and the exhibition gallery were for the general public, while the reading room was to be used exclusively by scholars. Since the library was both a museum and a place of study, Cret consciously—and inventively—broke with the Beaux-Arts convention that required plans to have a single central axis, and created a biaxial plan in the form of an elongated U. The central bar houses the gallery in the front, facing north, and the reading room behind it, while the shorter flanking wings contains the theater on one side and the administrative offices on the other. There are two identical entrances, one for the public and one for scholars.2 Since the reading room was the symbolic heart of the building, Cret wanted to express this difference by making it taller, but Folger insisted on a uniform roof parapet. Cret’s solution is better, but his client, who had been chairman of Standard Oil, was used to getting his own way.

Paul Philippe Cret, Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, D.C., 1932

The Folger Shakespeare Library abounds with symmetries, inside and out. The two entrances mirror each other on the long main façade. Although functionally different, the east wing containing the theater mirrors the west wing in its overall dimensions. The entrances to the exhibition gallery face each other at the two ends of the vaulted room. A large fireplace occupies the precise center of the long wall in the reading room. At the same time, Cret was hardly a slave to symmetry. At Folger’s suggestion, he made the elevation of the office wing more elaborate than its function demanded, since it is the first thing you see as you approach the building down East Capitol Street.

SYMMETRY AND AXES

Beaux-Arts-trained architects took symmetry so much for granted that John Harbeson, Cret’s protégé and partner and the author of a famous teaching handbook, felt obliged to add a chapter titled “The ‘Unsymmetrical’ Plan.” He pointed out that unbalanced programmatic requirements, or odd-shaped sites, sometimes called for unsymmetrical plans, but observed that such plans were more difficult to compose, and should not be undertaken lightly. It was very clear from his description that the “unsymmetrical” plan—the word always in quotation marks—was a rare bird.

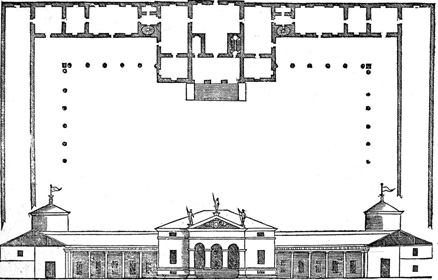

The source of Beaux-Arts architects’ interest in symmetry was the architecture of the Renaissance, which they either visited in person or studied in historical treatises. One of the most influential authors was Andrea Palladio, whose Four Books on Architecture was widely consulted by architects, since it was heavily illustrated. An edition by the eighteenth-century British architect Isaac Ware was for long the most authoritative English translation. To achieve maximum accuracy, Ware traced the original woodcuts, which meant that his engravings were actually mirror images of Palladio’s drawings. The reader hardly notices, however, since the buildings illustrated are all strictly symmetrical.

“Rooms must be distributed at either side of the entrance and the hall, and one must ensure that those on the right correspond and are equal to those on the left so that the building will be the same on one side as on the other,” wrote Palladio, although his stated logic for this arrangement—that “the walls will take the weight of the roof equally”—is dubious. An earlier architect, the Florentine Leon Battista Alberti, provided a more compelling rationale: “Look at Nature’s own works … if someone had one huge foot, or one hand vast and the other tiny, he would look deformed.”

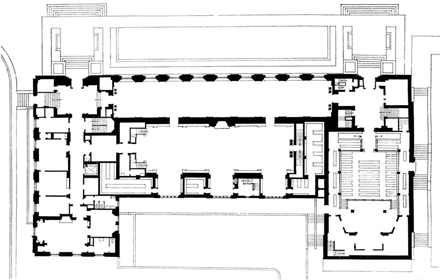

My wife and I and two friends once spent eight days in a Palladio villa in Finale di Agugliaro in the Veneto. The sixteenth-century Villa Saraceno, designed relatively early in the architect’s career, is one of his smallest houses, only five rooms. The grand courtyard shown in Palladio’s drawing was never built, although a small portion on the east side was completed in the nineteenth century, giving the villa an endearingly lopsided appearance. Palladio would have disapproved, for his plan is perfectly symmetrical. The east side of the house mirrors the west, an imaginary line bisecting the wide entrance stair, the loggia, and the T-shaped sala, or reception room. Palladio’s villas have only servants’ stairs, never grand staircases, and this one is no exception. The stair is carved out of the sala, balanced by a camerino, or small room, on the opposite side. Another line crosses the length of the sala, runs through the two side rooms, and extends into the two arms of the barchesse, or agricultural outbuildings. The two side rooms have smaller adjoining chambers, and each is lined up along a minor axis.

Andrea Palladio, Villa Saraceno, Finale de Agugliaro, c. 1550

Palladio’s axes were the lines of an idealized geometrical diagram, but they also governed the locations of the doors and windows. As a result, when we opened the large front and back doors, we could see straight through the house. Moving from room to room, we were always following one of Palladio’s axes. Lining up the doors and windows creates long views through the house, and also brings the outside indoors in a way that is curiously modern. In addition to the many symmetries, small and large, inside and out, the villa has beautiful proportions, grand scale, and a sturdy simplicity. Together, these produce a palpable feeling of order and calm, pleasing to both the mind and the eye.

Palladio’s strict adherence to axial geometry was based on ancient precedents such as the Pantheon, which he studied on several visits to Rome. The Romans derived the idea of symmetry—like the word itself—from the Greeks. The Oxford mathematician Marcus du Sautoy writes that the ancient Greek symmetros meant “with equal measure,” and referred to the five Platonic solids—the tetrahedron, cube, icosahedron, octahedron, and dodedecahedron. To the Greeks, symmetry was a precise concept that could be demonstrated by geometry. But an interest in symmetry is hardly confined to the ancient Greeks, for symmetry is found in the plans of buildings of diverse civilizations: the Temple of Thebes at Luxor, the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, Angkor Wat in Cambodia, the Forbidden City in Beijing, and Shinto shrines in Ise. In all these examples, symmetry in plan is allied to ritual and ceremony, and also produces an aesthetic experience, a sense of harmony and balance reflecting beauty or perfection. Indeed, the desire for symmetry in our surroundings, whether it is placing a bowl of flowers in the center of a table or candlesticks on each side of a mantelpiece, appears to be universal.

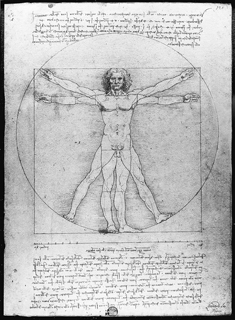

Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, c. 1487

Why is architectural symmetry so satisfying? As Leonardo da Vinci’s famous drawing demonstrates, the human body incorporates many mirroring symmetries, it has a right side and a left, a back and a front, the navel in the center. Du Sautoy writes that the human mind seems constantly drawn to anything that embodies some aspect of symmetry: “Artwork, architecture and music from ancient times to the present day play on the idea of things which mirror each other in interesting ways.” Architectural symmetry may involve geometrical patterns in floor tiles or panels on a door, but it can also be palpable. When we are inside a Gothic cathedral, for example, we experience many changing views, but when we walk down the main aisle—the line where the mirror images of the left and right sides meet—we know that we are in a special relationship to our surroundings. And when we reach the intersection of the transepts and the choir and stand below the crossing under the spire, we know we have arrived.

The architects whom Nikolaus Pevsner called the “pioneers of modern design”—Henry van de Velde, Otto Wagner, Josef Hoffmann, Peter Behrens, Adolf Loos—explored new, unhistorical shapes and forms but they did not reject symmetry. That fell to the succeeding generation, which thumbed its nose at tradition, especially Beaux-Arts tradition. “Modern life demands, and is waiting for, a new kind of plan both for the house and for the city,” wrote Le Corbusier. To him “new” meant unsymmetrical; like historical ornament and old-fashioned craftsmanship, symmetry had to go. The plans of representative modern buildings of the 1920s and 1930s are all determinedly unsymmetrical. Although the eight columns supporting the roof of Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion are arranged on a regular three-square grid, you can hardly tell, since the walls that surround them are so unevenly positioned. The wings of the Bauhaus building pinwheel in different directions and at different heights, and nothing in Fallingwater mirrors anything else. Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, considered an exemplar of the International Style, looks symmetrical but isn’t—it is not a perfect square, and while its grid of structural columns is more or less regular, the regularity is frequently undermined. “The house must not have a front,” Le Corbusier wrote, so the front door is not on the arrival side but on the opposite side of the house. The door is in the center of the façade, but its location is intentionally compromised since there is a column directly in front of it. Classical buildings always have an even number of columns, to ensure that a space falls in the center opposite the entrance; the Villa Savoye, by contrast, has five columns a side.

Mies van der Rohe made the plan of the Farnsworth House unsymmetrical, as we have seen, but this turned out to be one of the last buildings he so designed. At the Illinois Institute of Technology, which he planned, and where he was campus architect for twenty years, all the buildings that he designed are symmetrical in plan—the boiler plant as well as the chapel. Crown Hall, the school of architecture, is the most celebrated building at IIT, a clear-span, single-room design whose left and right sides mirror each other. The Seagram Building is likewise planned on an axis, which is emphasized by the flanking reflecting pools of the plaza and the four elevator cores of the lobby. Mies’s biographer Franz Schulze has pointed out the similarity in axial planning between the Seagram Building and the building it faces across Park Avenue, the venerable Racquet and Tennis Club, designed by the Beaux-Arts graduate Charles McKim. The implication is that Mies planned his building to fit into its surroundings. This is true, but it is also true that by then he had rediscovered the power of symmetry, and used it in all his projects.

Eero Saarinen started his career as a follower of Mies, and his first major commission, the General Motors Technical Center, was inspired by the Illinois Institute of Technology. Although a few of Saarinen’s later designs were unsymmetrical, like Morse and Stiles Colleges at Yale, which have been compared to an Italian hill town, symmetrical plans became his trademark. Symmetry came naturally to Saarinen, since he had studied architecture at Yale at a time when the curriculum was still organized along Beaux-Arts lines.

Louis Kahn was another second-generation modernist who rediscovered symmetry. The plans of early projects such as the Yale University Art Gallery and the Richards Medical Building are both resolutely unsymmetrical. But in later buildings, Kahn returned to the Beaux-Arts planning principles he had absorbed as a student under Paul Cret. Indeed, his most admired buildings—the Salk Institute, the Kimbell Museum of Art, the library at Phillips Exeter Academy—while modern in conception and design, gain much of their timeless quality precisely from their symmetrical plans.

READING THE PLAN

Architectural plans may puzzle the layman, but once mastered, they are a rich source of information. Plan drawings follow a few simple conventions. An architectural plan is conceived as a horizontal cut through the building at approximately waist height. Walls are indicated by two thick lines, sometimes filled in with a solid tone or cross-hatching, a technique that Beaux-Arts architects called poché; columns appear as circular or square black dots; windows are thin solid lines. Doors are sometimes shown and sometimes not; if they are drawn they are usually fully open, sometimes a quarter arc represents the swing. Dotted lines indicate something above the horizontal cut, such as a soffit, a beam, or a skylight. Plans may include flooring patterns, such as wooden decks or stone paving, and may use stylized patterns to denote special areas such as vestibules or lobbies; gridded tile patterns identify bathrooms, kitchens, and service rooms. Built-in furniture, such as bookshelves or window seats, is always shown. Sometimes movable furniture such as beds, desks, tables and chairs, and sitting arrangements is indicated, but more often rooms are empty. North is always up the page, unless otherwise indicated.

A floor plan represents the arrangement of walls in a building, but because it includes door openings it also describes movement. By tracing a line from the front door to the auditorium of a concert hall, for example, one can get an impression of the sequence of vestibules, lobbies, staircases, and twists and turns that form the processional experience. Since a plan also shows the location of windows, it is possible to see the sources of light, the views, and whether a room is sunny. “Reading” a plan involves imagining the space. Is the room a simple square, or is it lined with niches, say, or bookshelves, or surrounded by a colonnade? If the space is long and narrow, what does one see at the far end, and if it is circular, what is in the middle?

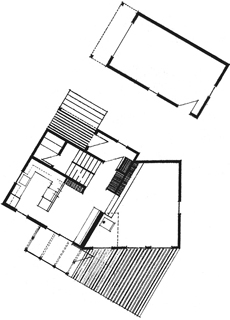

Most people are familiar with domestic plans, which are often reproduced in the real estate sections of newspapers and in magazine advertisements. The plan of the Ferrero House in rural Quebec, which was discussed at the end of the previous chapter, is skewed, since the lower portion of the dogleg is oriented due south, while the front of the house faces the angled road. The freestanding garage creates a partially enclosed court. The house is entered through a small porch with oversized steps, wide enough to sit on and hold flowerpots. The mudroom has a deep cupboard for umbrellas, walking sticks, and other outdoor paraphernalia. In this drawing, cupboards and closets are cross-hatched to distinguish them from habitable spaces. From the front door you get a long view—the longest in the house—through the hall, dining area, and sunroom to the exterior. The tiny hall is the heart of the house. From here you can take the stair to a sauna on the upper landing, and continue to the bedroom floor; you can go down to a powder room on the lower landing, and continue to the basement; or you can go straight through to the dining area. Dining and kitchen are in one room, separated by a low wall; sliding doors lead into the sunroom, which connects to a deck outside. Three steps lead down to the living room. The steps are necessary, since the concrete living room floor (which provides the thermal mass of this passively heated solar house) rests directly on the ground. The steps are wider here, too, and one of them extends across the front of the bookcase.

Witold Rybczynski, Ferrero House, St. Marc, Quebec, 1980

There are only two windows on the north side of the house: one in the mudroom and one in the kitchen, giving a view down the driveway to the road. Most of the windows face due south or south-southwest, to get the maximum benefit of the sun during winter days. That is achieved by the dogleg plan, which also makes a small and compact house feel more lively, creating odd and unexpected views such as the diagonal view from the kitchen to the living room, and interesting spaces such as the partially enclosed entrance court. The challenge was not to make the house imposing—it is much too small for that—but to keep it from feeling mean and cramped. Hence the ten-foot-wide porch steps, the long vista from the front door, and the lowered living room floor, which creates a ten-foot ceiling. The dotted line in the living room indicates an opening up to the second floor; the wood-burning stove stands against a thick brick wall (more thermal mass), and a tall window rises the full height of the house. Taking a page from Robert Venturi, this is a small building with a large scale.

The plan of the Ferrero House is solid and compressed, the compactness reflecting its windblown site in a northern climate. The plan of the Villa Pacifica in sunny Southern California, on the other hand, is expansive. The architect, Marc Appleton, was approached by a television and Broadway producer who owned a beautiful site overlooking the Pacific, and wanted a house that would remind him of his native Greece. The result is a house that resembles a Greek village with thick walls, small windows, outdoor staircases, and vaulted roofs; even the view is eerily Cycladic, with the blue Pacific standing in for the Aegean.

Appleton & Associates, Villa Pacifica, California, 1996

The house encloses several shaded courtyards and some of the movement between rooms takes place out of doors. The plan looks like a casual arrangement of volumes, but it incorporates a strong axis. This axis begins at the entrance gate to the compound, moves along an outdoor walk under a trellis beside the kitchen courtyard, arrives at the front door, and continues into the hall, terminating in a loggia, an outdoor room that overlooks a terrace high above the Pacific. All the spaces fall on one side or the other of this imaginary north–south line: the garage, kitchen courtyard, kitchen, and dining room on the west; a guest cottage, the garden courtyard, and the living room and study on the east. Obviously, one is drawn to the terrace with its spectacular view, but in some ways the key space of the house is the loggia, which also serves as an outdoor eating area. With its central position at the head of the axis it firmly anchors the rest of the rooms.

The plan of the Villa Pacifica minimizes western exposure and opens the courtyards up to the morning sun. Most of the house is orthogonally planned, to make the best use of the narrow lot, with the exception of the living room, which is cranked slightly to the west, to give a better view of the sunset and a distant landfall on the coast. As in the Ferrero House, the angle creates some unexpected views and interesting spaces, and it also undermines what might have been a staidly symmetrical plan—the loggia too neatly sandwiched between the dining and living rooms. “If the geometry had all been orthogonally organized, it would have looked overly planned, like an architect did it, rather than slightly accidental,” explains Appleton. “We were at self-conscious pains to create spaces and details that did not in the end look self-conscious.” Appleton’s approach to the design of the villa is unusual in that he largely removes himself from the end result. “I’ve always admired Billy Wilder’s movie direction, because you’re not aware of it, only of the story he’s telling,” he observes.

MOVEMENT

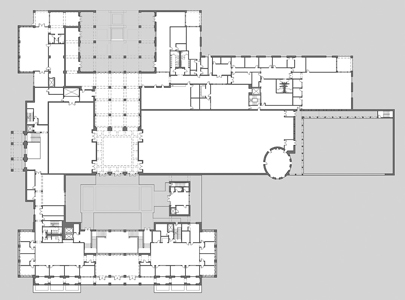

Plans reveal a lot about an architect’s intentions. At first glance, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown’s plan of the Sainsbury Wing’s main gallery floor appears unremarkable. The wing was specifically intended to hold the National Gallery’s early Renaissance collection of paintings, and the curators requested a variety of rooms of different sizes to provide an intimate setting for the collection. The challenge for the architects was to lay out the rooms without creating a labyrinth—or odd-shaped galleries that would distract from the art.

Venturi made one decision early on that had an important effect on the plan. The site of the Sainsbury Wing is an irregular shape, thanks to surrounding angled streets. Instead of squaring off the building to create an orthogonal plan—as most architects would have done—Venturi exploited the irregularity. He explained his reasoning:

When it came to the plans, I thought a lot about the way Lutyens in London had fitted his great Midlands Bank building onto an awkwardly shaped City site. Look, too, at the way Wren’s classical churches were made to fit old medieval sites. In Rome, the great palaces are placed into a much older city plan and sometimes they are not as regular as they appear, in fact their regular rectangular grids are often quite distorted.

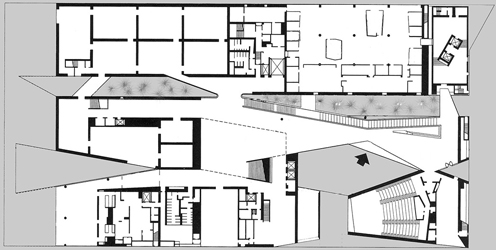

In the Sainsbury Wing, the rooms are arranged in three rows, running north–south the length of the building. The four enfiladed rooms of the central row form a kind of spine. They are the largest and tallest galleries, and are given additional importance by their architectural treatment. The rooms in the east row are slightly smaller and lower, and have windows that look down into the staircase; the rooms in the west row are the smallest and lowest—and the least rectangular, since they absorb the irregular angle of Whitcomb Street. The dotted lines indicate clerestories that introduce daylight from above.

Venturi, Scott Brown & Associates, Sainsbury Wing, National Gallery, London, 1991

The galleries are reached by climbing the wedge-shaped stair from the entrance lobby; the glass wall on the right overlooks Jubilee Walk and Wilkins’s National Gallery. The stair ends at a landing opposite a bank of elevators; on the right, a bridge in the form of a circular room connects to the old building, on the left is the entrance to the new galleries. From here, through four door openings, the visitor has a view of Cima’s Incredulity of St. Thomas on the far wall. The distance appears greater than it is, since the openings are made progressively narrower, an example of so-called forced perspective. The visitor is pulled in this direction to the central gallery, where another visual axis, down the central spine of rooms, terminates in the Demidoff Altarpiece, a fifteenth-century polyptych. The two axes—and the varying heights of the rooms—create a hierarchy within the space and give a subtle sense of organization to the sixteen galleries. Once the visitor enters the rooms, there are only walls with paintings, no architectural distractions.

Axes on plans are imaginary, yet they are among the architect’s most powerful tools. A good example of how axes can help to organize a large and complicated program is the George W. Bush Presidential Center, designed by Robert A. M. Stern. The site is at the edge of the campus of Southern Methodist University in Dallas. Like all presidential libraries, the center contains a museum and presidential archives, but it also houses a policy institute, which will be used by students and faculty as well as visiting scholars. To distinguish the different functions, Stern created two separate entrances, one on the north (facing the arrival road) for the presidential library, and one on the west (facing the campus) for the policy institute. The entrance to the library follows a north–south axis that begins in the parking lot, arrives in a colonnaded entrance court, and continues through a vestibule until it terminates in a tall square space—Freedom Hall. The hall ends the entry sequence and provides access to the museum, and to a large space for temporary exhibitions; directly ahead is an outdoor terrace. A second axis, east–west, aligns with the entrance portico of the institute, which faces the end of Binkley Avenue, an important campus thoroughfare. The two axes cross in Freedom Hall, a tall space topped by a limestone lantern that functions as a sort of beacon. The lantern is visible as one approaches the library from the parking lot, and also terminates the vista down Binkley Avenue. According to Stern’s partner, Graham S. Wyatt, “Axiality and symmetry are formative principles that everyday people understand as they experience them in three dimensions, and for a lot of people they imply formality, maybe even a degree of gravitas.” Wyatt points out that secondary uses such as the security screening area and the gift shop were intentionally located “off axis” so as not to compromise the sense of occasion as one enters and leaves the building.

Robert A. M. Stern Architects, George W. Bush Presidential Center, Dallas, 2013

The presidential library, which was designed with the landscape architect Michael van Valkenburgh, includes several memorable outdoor spaces, which further structure the plan—two anchoring the north–south axis, and two anchoring the east–west. A colonnaded entrance court with a fountain is balanced by the outdoor terrace—an important amenity in Texas, which has mild springs and autumns. The terrace is accessible both from the library and from the institute. On the west side, a circular drive creates a formal arrival space in front of the institute entrance, while at the other end of the east–west axis is a reproduction of the White House Rose Garden. The Rose Garden is immediately adjacent to a replica of the Oval Office, a staple of presidential libraries, but here oriented in the southeast corner of the building, exactly as it is in the White House.

Although portions of the Bush Library, such as the entry court, and the west and south façades of the institute, rely on symmetry, this is not really an unsymmetrical Beaux-Arts plan in John Harbeson’s sense. Rather, it recalls the plans of a first-generation modernist such as Eliel Saarinen, who loosened up Beaux-Arts planning without altogether giving up its principles. While the Bush Library relies on axiality, the Stern office has elsewhere explored combining axiality with informal planning. “The residential colleges we are currently designing for Yale are a good example,” says Wyatt. “The main axis of the plan is a walkway that ends in a square where a new axis re-centers and redirects the movement in a way that is picturesque rather than formal.”

ORIENTATION AND DISORIENTATION

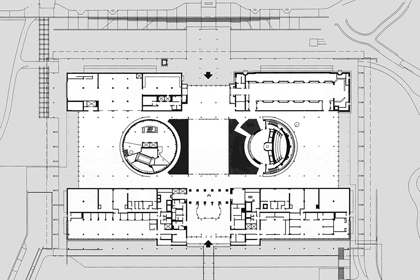

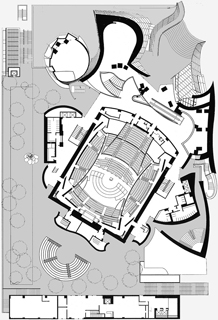

Two recent museums face each other in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park: the California Academy of Sciences, designed by Renzo Piano, and the de Young Museum, designed by Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron. Both plans generate the architecture—in Le Corbusier’s sense—but they do so in different ways. The California Academy, a museum of natural history, is a large rectangular building. The public entrance is on the north side, precisely in the center; the staff entrance is opposite, on the south. A line between the entrances divides the plan in two equal halves. The two symmetrical rectangles flanking the main entrance on the north side are slightly different: one contains a replica of the African Hall that had been part of the neoclassical building that once stood on this site but was irreparably damaged in a 1989 earthquake; the other houses a café and museum shop. The two blocks on the south side contain offices, research spaces, and classrooms. The space in the center contains exhibits and two ninety-foot-diameter spheres, one opaque and enclosing a planetarium, the other transparent and containing a rain forest exhibit. The darkly shaded areas on the drawing are a saltwater tidal pool and an artificial coral reef. The coral reef is deep enough to be visible from the museum’s basement, which also houses aquariums. The rectangle in the precise center of the plan, where the two axes cross, is what Piano calls the Piazza, a glass-roofed atrium that is used for receptions and social events.

Traditional science museums are rabbit warrens of dark rooms, one for insects, one for fish, another for rocks, and so on. The chief impression of the California Academy is of a large exhibition hall that, thanks to the glazed end walls and many skylights, is brightly lit. Although Piano’s axial plan demonstrates Beaux-Arts planning rigor, his architecture is the antithesis of the Beaux-Arts—steel and glass rather than masonry, lightweight rather than heavy, inspired by technology rather than history. Yet the axial symmetry and the mirroring of forms—the two spheres—provide a clear and simple sense of orientation. This is important, for the huge hangar-like space is filled with an array of exhibits and displays crowding in upon one another. The discipline of the plan binds the whole thing together.

Facing the California Academy of Sciences across a wide landscaped concourse is the de Young Museum, which likewise replaced a predecessor damaged in the same earthquake. The art museum’s plan is rectangular and roughly the same overall dimensions as the Academy, but the interior is organized differently. Architects have sometimes used triangular modules to structure a plan—I. M. Pei often used isosceles triangles (notably in the plan of the East Building of the National Gallery)—but there is nothing modular about Herzog and de Meuron’s triangulated plan. Irregular wedges are cut out of the building to create penetrating spaces and trapezoidal courtyards, walls do not line up, nothing mirrors anything else, there are no axes.

Renzo Piano Building Workshop, California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, 2008

Jacques Herzog & Pierre de Meuron, de Young Museum, San Francisco, 2005

The entrance is through a pinched tunnel that leads into a polygonal-shaped open-air courtyard. The unmarked, uncanopied front door is located almost haphazardly on one side. The backdrop to the odd-shaped lobby is a glass wall looking into a fern garden. To get to the museum you turn left and walk through another bottle-necked space until you reach a trapezoidal two-story atrium, dominated by a large painting by Gerhard Richter. On the left is a wide stair going up to the second floor, on the right is a long—extremely long—stair that descends to the lower level. A diagonal path, next to another court, leads to the galleries; another diagonal takes you to the café.

What are Herzog and de Meuron up to? Nothing in their plan takes precedence, there is no right way or wrong way to move through the building, any route that you choose is all right. For example, you can enter through the distinctly ungrand front door, or else via the café terrace, under a dramatic overhanging roof. Herzog and de Meuron’s approach is different from the clear hierarchy suggested by traditional plans. It is also different from the idealized universal space of Renzo Piano’s Academy of Sciences. The de Young doesn’t have an obvious structure, but it has character, and the fractured spaces evoke earthquakes and shifting tectonic plates. Was this allusion intended by the architects? Maybe. “Architecture is like nature—it tells you something about yourself,” Jacques Herzog said in an interview. “Nature is very empty—it confronts you with yourself and your experience of it and what you know about yourself in the context of a landscape, river, a rock, a forest, a shadow, the rain.” In other words, their architecture is something of a blank slate.

The lack of visual axes and hierarchy in the de Young is only slightly disorienting; this is not a maze. The one place where the architecture quiets down is in the galleries themselves. The rooms in the northwest corner of the ground floor, for example, contain twentieth-century art. The visitor slides in at an angle, but from then on continues in a conventional fashion from one rectangular room to the next. Upstairs, a series of enfiladed top-lit rooms provides an appropriate setting for the museum’s collection of nineteenth-century American art. In the galleries, the old rules prevail.

Gehry Partners, Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, 2003

The plan of the de Young is consistent in its use of trapezoidal spaces and diagonal movement. But what is one to make of the plan of Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles? The walls gyrate and swivel according to mysterious hidden rhythms, the shapes defy logic, the forms seem to lack rhyme or reason. Yet Disney Hall is the result of a simple idea. “You have to have a nice room,” Gehry said in an onstage interview at an Aspen conference, referring to the concert hall. “Forget the exterior. It starts with that inside. That inside was the key issue.” The architect and acoustician Yasuhisa Toyota explored many shapes for the auditorium—some of them highly irregular—building large-scale models before settling on an arrangement with curving tiers of seats facing each other on all sides of the orchestra. For acoustical reasons, the auditorium was surrounded by a concrete enclosure. “That’s a box,” Gehry explained. “And on either side of the box are toilets and stairs. And you’ve got to join those toilets and stairs on either side with a foyer. That’s the plan.” When he said this, the Aspen audience laughed. He made it sound so simple, while the built result is obviously so complicated. Yet the underlying principle of Gehry’s plan is as simple as he described: box, toilets, stairs, a foyer, a front door.

How is it possible for five distinguished architectural firms to have such different approaches to planning a building?3 Asked whether he took the de Young Museum, which was built first, into account when he designed the California Academy of Sciences, Renzo Piano’s tactful response was that he didn’t think much about it. “This is what you get when you are yourself and they are themselves,” he said. A good answer. The differences between the California Academy and the de Young Museum, like those among the Sainsbury Wing, the Bush Library, and Disney Hall, are less the result of different functions, settings, or sites than of different architects being themselves. Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown are interested in adapting history to modern needs, but they also delight in exploiting the quirky and even awkward disjunctions that sometimes arise in the process. Theirs is a modern reinterpretation of old ideas, often keeping those old ideas at arm’s length. Robert A. M. Stern, on the other hand, embraces history. “Our firm welcomes new ideas, and we cherish ideas from the past,” he has written. “We believe that everything is possible, but that not everything is right.” A concern for continuity is evident in the plan of the Bush Library, which does not strive for novelty but is satisfied with the old architectural verities: clarity, order, balance.

The plan of the California Academy, on the other hand, suggests that Renzo Piano is only slightly interested in the past. The plan has a neoclassical simplicity, but it is merely a starting point for his real passion, which is building. This plan is less a generator than a sort of armature. It is as if he said, “We have to have a plan, so let’s keep it very simple, and let’s focus on how the building is constructed.” Not for nothing does he call his office the Renzo Piano Building Workshop.

Herzog and de Meuron’s plan for the de Young Museum is the most conventionally modernist of the group—that is, it rejects tradition and history and is designed without recourse to axes, symmetry, lines of movement, vistas, or any perceived geometrical order. The result can be appreciated in purely graphic terms, as if it were a sculpture or a large woodcut. It is no coincidence that in the early years of his architectural practice, Jacques Herzog pursued a parallel career as a conceptual artist.

While Herzog and de Meuron seem interested in pushing the plan in a new, aesthetic direction, the plan drawing of Disney Hall seems almost like an afterthought. Modern architecture’s greatest iconoclast (after Le Corbusier), Gehry has upended one of its long-standing tenets; for him, the plan is not the generator. His preliminary sketches are never plans; instead the squiggly ink lines portray a three-dimensional image of the building. Then come the crude paper study models, more elaborate wooden models, the shapes mapped by computer software, and only at the end the floor plan.

So, is the plan the generator? In many cases, it remains primary. An ordered plan provides an image in the mind’s eye that guides us through a building. It helps us find our way. In that regard, symmetry, especially axial symmetry, remains a useful tool. At the same time, having broken free of the conventions of symmetrical planning, there is no easy return. Architects no longer feel obliged to present the public with a simple diagram. Sometimes, as in the de Young, a sense of adventure is required to learn what is around the corner. The master of this approach is Gehry. In Disney Hall, the sense of excitement in the chaotic lobby spaces heightens the experience of concertgoing. Yet, in the hall itself, Gehry reverts to tradition and designs a serene space for listening to music, axially planned and perfectly symmetrical.