III

THE ALEXANDRIAN LIBRARY

300 BC—40 BC

A FRAGMENTARY PIECE of papyrus of the second to third century AD describes the city of Alexandria as ‘a universal nurse’, harbouring soldiers from Macedonia, settlers from mainland Greece, Arabs, Babylonians, Assyrians, Medes, Persians, Carthaginians, Italians, Gauls, Iberians and a large and cultured Jewish population. Protected as it was by the island of Pharos lying offshore, the site had many natural advantages. When Alexander the Great sailed past it on 20 January 331 BC, he immediately recognised its potential and ordered Dinocrates, the architect accompanying him on his Egyptian adventure, to lay out a grand new city there. Alexander, who died in 323 BC, a year before Aristotle, never saw his namesake; in the distribution of empire that followed Alexander’s death, his half-brother, Ptolemy Soter (see plate 13) got Egypt. But Dinocrates laid out a powerfully triumphant city: two great intersecting avenues divided it into four unequal parts; shady colonnades of marble lined the streets; the stone houses were built over vaulted cellars to keep cool the underground cisterns filled with fresh water; huge docks and warehouses rose along the harbour front. In The Thirty-Second Discourse, Dio Chrysostom marvelled at the grandeur and power of the new metropolis: ‘Not only have you a monopoly of the shipping of the entire Mediterranean by reason of the beauty of your harbours, the magnitude of your fleet, and the abundance and the marketing of the products of every land, but also the outer waters that lie beyond are in your grasp, both the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean whose name was rarely heard in former days.’1 The Macedonian, Ptolemy Soter, ruled supreme in the former ancient empire of the Pharaohs. He too inspired a renaissance - nothing to equal the Royal Museum or the Alexandrian Library had ever been seen in the ancient world. The Museum, part of the royal palace in the Greek quarter of the city, had a public walk, a curved exedra with marble seats, a common room and a refectory. It was connected to the Library by a covered marble colonnade; inside the Library were ten great halls, lined with shelves and cupboards, all numbered and titled, housing a vast collection of manuscripts. Another, smaller, library was built near the Temple of Serapis in the Rhakotis, the Egyptian quarter.

Plate 13: Ptolemy Soter, who founded the great library at Alexandria and was the first of a dynasty of Macedonian emperors who ruled in Egypt from 323 BC

Each of the Library’s halls was dedicated to a separate subject. Where is my man Theophrastus in this huge place, I am wondering? Who is reaching to pull Enquiry into Plants down from its numbered shelf? Aristotle’s death marked the end of the great classic period in Greek literature but just as he and the great tradition of which he was part perished, a new age began in Alexandria. When Aristotle had first started to collect books for the Lyceum’s library, he was considered a pioneer, an innovator. Now Ptolemy Soter began to put together something far more ambitious, employing perhaps a hundred scholars to seek out and translate texts for its shelves. He gathered together poets, philosophers, scientists, mathematicians (Euclid was one of them), as well as men of letters to build a new civilisation here in Alexandria, inspired by Hellenic ideals. But though the city he brought into being was new, the country in which it stood had seen a culture very much more advanced than the Hellenic civilisation that Ptolemy now imposed on it. At the time of the Pharaohs, long before Theophrastus embarked on his great work, the Egyptians had already created hieroglyphics for 202 different plants including opium poppy, fennel, acacia and reed.2 They had learned how to make paper from papyrus as Theophrastus describes in his Enquiry into Plants;3 they knew how to embalm bodies using plant extracts. Knowledge in ancient Egypt, though, was largely bound up with the priesthood, not secular as it had been at the Lyceum and the Academy in Athens.

Among those who went to Alexandria was Demetrios of Phaleron. It was he who first suggested that Alexandria should have a museum and a library and he who gathered in the first manuscripts for Ptolemy Soter’s collection. Exiled from Athens, he wanted to make Alexandria into an Athens across the sea. An orator and a statesman as well as a philosopher, Demetrios was a follower of Aristotle, a pupil and friend of Theophrastus. So it seems quite likely that Athanaeus was right and that at least some of the Peripatetics’ books came to Alexandria. Demetrios would have been the perfect intermediary. But, with a patron as cultured as Ptolemy to please, he would also have wanted only the best. So perhaps he acquired the most original of the manuscripts, leaving the rest with Neleus and his heirs to be consigned later to the pit, the moths and the worms. Both accounts could be true. The Library was most probably founded soon after Demetrios’s arrival in Alexandria around 307 BC, when he secured large grants of public money to augment the collection. Contemporary accounts suggest that in the first ten or twelve years, he could have brought in as many as 200,000 separate works, transcribed on rolls of papyrus. Like the American collectors, Pierpont Morgan, Huntington and Paul Getty, all of whom gathered cocoons of old culture around them in a new country, Ptolemy Soter cast his net wide. When he ran out of Greek texts to collect, he brought in foreign ones, particularly those of the two great empires of the ancient Eastern world - Assyria in the east and Egypt in the south.

Demetrios of Phaleron was the first of a long list of distinguished librarians: Zenodotus of Ephesus (282-C.260 BC), Callimachus of Cyrene (c.260-c.240 BC), Apollonius of Rhodes (c.240-c.230 BC), Eratosthenes of Cyrene (c.230-195 BC), Aristophanes of Byzantium (195-180 BC), Apollonius the Eidograph (180-C.160 BC), Aristarchus of Samothrace (c. 160-131 BC). Unfortunately, when Ptolemy’s son took over the city, Demetrios fell out with him (overspending? Or just yesterday’s man?) and was banished to Busiris in Upper Egypt. He died in 282 BC, bitten by an asp; some said he had been murdered. With his death, the direct link with Theophrastus came to an end.

The Ptolemys’ empire lasted for 300 years, the city more than twice as long. It was a treasury of learning and science, preserving all the hard-won knowledge of the Greeks, as well as a great deal of learning from the empires that Alexander had conquered. There was a strict embargo on imported books. All vessels coming into the port were searched and if any books were found aboard, they were confiscated. Copies of the confiscated volumes were made for their owners, while the originals were kept for the Alexandrian Library.

The second Ptolemy also commissioned the most ancient translation of the Old Testament. He brought in seventy-two Jewish translators and kept them cooped up on the island of Pharos until they had finished the job. The Preface to the King James Bible (1611) acknowledges his primacy: ‘It pleased the Lord to stirre up the spirit of a Greeke Prince (Greeke for dicent and language), even of Ptoleme Philadelph, King of Egypt, to procure the translating of the Booke of God out of Hebrew into Greeke … Therefore the word of God, being set foorth in Greeke, becometh hereby like a candle set upon a candlesticke, which giveth light to all that are in the house …’ Dragged regularly as a child to the small thirteenth-century church that crouches at Llanddewi Rhydderch in Wales, I sometimes read that passage during tedious sermons. As a word, Philadelph took my fancy, as sop-or-if-ic did in Beatrix Potter’s tale of Peter Rabbit. Then, in my first garden, I met the man again as a shrub, the syringa or mock orange (Philadelphus coronariusj, sweet-smelling, white-flowered, and introduced from Turkey into Europe by the Flemish ambassador Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, in 1562. But syringa (it comes from the Greek word syrinx or pan pipe) was also the common name given to lilac because both shrubs have wood that is hollow and pithy and both were used by the Turks to make musical pipes. It was a muddle, having two completely different shrubs sharing the same common name. The French botanist Jean Bauhin resolved it in 1623 by giving the king’s name, Philadelphus, to Gerard’s ‘white pipe tree’.

Philadelphus the king died in 246 BC so did not witness the cataclysmic destruction of his city, sacked by the Roman dictator Caesar in 47 BC. By then more than half a million rolls and scrolls were piled upon the labelled shelves of the ten great halls. Some (the greatest treasures) had already been given to Caesar by Cleopatra. Some were destroyed when the citizens of Alexandria, under a military commander called Achillas, rose up against Caesar and marched on the city. Caesar deliberately set fire to the Egyptian fleet in Alexandria’s harbour, but the wind, blowing onshore, set alight the buildings of the waterfront too. Did the Library burn? No, not then. Later, religion accomplished what war had left alone. The gaps on the Library shelves left by Clepatra’s ‘gift’ to Caesar, were conveniently filled by Antony, who gave Cleopatra 200,000 rolls from the library sacked at Pergamum. Tough skins joined Egypt’s brittle, frail paper. Knowledge fragmented came together again. And was Theophrastus still there in that great repository? No catalogue survives. It can’t be known for sure. But the work he produced was the kind of work in which the Library specialised. Unlike the Athenian schools, the Alexandrian Museum and Library were not places of philosophical controversy; they were academies of technical knowledge, especially that relating to medicine and the natural sciences. The work that Theophrastus started in Athens was central to what mattered in Alexandria, though they did not build on what he had done. While the Peripatetics had written as natural scientists, the Alexandrian scholars wrote as encyclopaedists, one step removed from the actual subject matter. Commentary was their forte. They explained the classical texts but did not, in Theophrastus’s field at least, initiate new work. In human anatomy and physiology it was different.4

’I shall not recapitulate the disasters of the Alexandrian Library,’ wrote Edward Gibbon, ‘the involuntary flame that was kindled by Caesar in his own defence, or the mischievous bigotry of the Christians who studied to destroy the monuments of idolatry’5 But the survival of knowledge, the thread that connects us, now, with them, then, was jeopardised by enemies more insidious than fire and war, less dramatic perhaps but just as threatening. Water trickles through the roof of the Library, damp pervades the parchment and papyrus, mould slowly spreads over the seminal words, mice scrabble among the scrolls, shredding the soft paper for their babies’ nests, moths lay their eggs between the undisturbed layers of skin. Nearly 700 years, the space between us and the medieval scribes of the fourteenth century, stretches between Theophrastus’s death and the destruction in AD 391 of the Temple of Serapis at Alexandria by the Christian emperor Theodosius I. What state was the Library in then? Theodosius was the last ruler to govern an undivided Roman Empire and during the twenty years (AD 375-395) of his reign, the new Christian Church sent out tough edicts. Paganism, in all its forms, must be destroyed. The temple dedicated to the Egyptian divinity Serapis, god of healing, was rebuilt as a Christian church and monastery. Did the small library, built at the portals of the old temple, survive this radical metamorphosis? If it did, it was not for long. After Theodosius came the Saracens. They attacked the city in the seventh century AD, and it was said that when the first camel entered the gates of Medina, bringing the spoils of war from Alexandria, the last, in an unbroken line, had not yet left Egyptian soil. Omar, the Saracens’ leader, was a fanatic convert to the cause of Islam. ‘No other book but the book of God,’ was his edict. Writing c.1227 in his Histoire des Savants, Ibn al Kifti describes the fate of the books. The Arab scholar Yahya al Nahawi tells Amr ibn al-As, the conquering Arab general of Egypt, about the extraordinary treasures contained in the Alexandrian Library. The soldier, who has never heard of the books, says he can do nothing until he has received instructions from the caliph Omar. He sends a message to Omar, telling him about the books and asking what he is to do about them. With cool fundamentalist logic, Omar replies, ‘If the books contain any thing which conforms to the Book of God (the Koran), the Book of God permits us to eradicate them. If they contain any thing which is contrary, they are useless. Proceed then to destroy them.’ Amr ibn al-As piled the books up in carts and distributed them among the 400 public baths of Alexandria. There, they were burned in the furnaces that heated the warming rooms. There were said to be enough of them to keep the fires going for six whole months.6

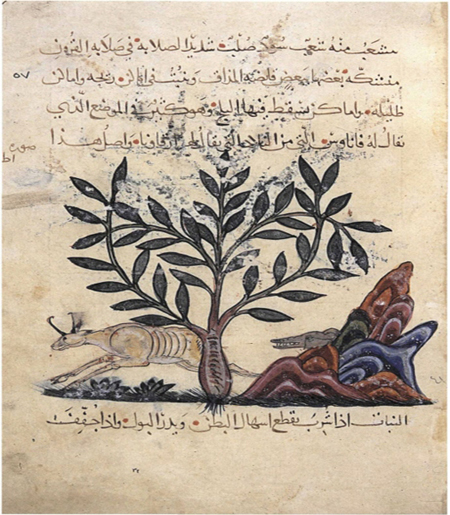

Plate 14: ‘Astragalus’ (commonly known as goat’s thorn or milk vetch) from a Dioscorides manuscript made and illustrated in the Islamic style in the middle of the thirteenth century

The Alexandrian Library was the first great library. And the first to be destroyed, though many were after that great bonfire of ideas in Alexandria. When, ten years later, Hulako conquered Baghdad, he ordered all the books of learning to be thrown into the River Tigris. The libraries of that unfortunate, cultured city were again destroyed by Mongols in the thirteenth century and by Tamerlane 200 years later. When European invaders conquered Tripoli in Syria during the Wars of the Crusades, Count Bertram Saint Jeal ordered its libraries to be burned; an estimated three million books disappeared in that purging. The Spaniards did the same with the ancient libraries of Andalusia when they reclaimed the region from the Arabs in the latter part of the fifteenth century. It seemed almost a prerequisite to establishing a new order. But somewhow, the ideas survived. And grew in importance.