THE ARAB INFLUENCE

AD 600—1200

JULIANA’S BOOK IS the earliest and most beautiful of Greek herbals. Although it was made at the beginning of the sixth century, nothing better emerged in Western Europe for almost a thousand years. But as learning plunged into an ever deeper black hole in Europe, there was a renewal of intellectual life in the East, centred at first in Edessa, Syria. Originally founded as a Macedonian colony, Edessa was well placed on the northern edge of the Syrian plateau both for those travelling on the north-south trade route and the east-west route, the Silk Road to China. Its position at the limit of the Roman Empire fostered an unusual degree of independence and prosperity. Syrian merchants travelled widely in Europe and North Africa; via the Red Sea, they also financed trade to South-West Arabia, India and Ceylon. The city’s position at the centre of a vast trade crossroads favoured the growth of an established group of cultured merchants, who by nature were against the domination of Rome and so for the Greeks (and their scholarship). There had been a medical school at Edessa since the fourth century. When, in 489, the Emperor Zeno declared it a hotbed of heretics and closed it down, the school’s Nestorian teachers moved to Nisibis, and then on to Djundishapur in Persia, 500 miles to the south. Djundishapur had also welcomed the neo-Platonists expelled from Athens in 529, and the method and content of their teaching had a powerful influence on Islamic philosophy. Nestorian doctors came to control the famous medical school at Djundishapur; cultures converged as Greek, Jewish, Persian and Hindu thinkers all met and exchanged ideas through the common language, Syriac.1 With the enthusiastic support of the Persian Emperor, a hospital and a medical school headed by Abu Zakariya Yuhana ibn-Masawaih (777-857), the son of an apothecary, were established in the city. It flourished for 300 years, until the Arabs conquered Persia and Baghdad became the principal centre of learning.

The Nestorian scholars2 are important because they translated Greek scientific works which might otherwise have remained in oblivion in Byzantine libraries. They had first fled east to Syria when the Roman Emperor Constantine conquered Byzantium and from their Syriac treatises translations were made into Arabic and Persian. The work begun in Edessa continued in Djundishapur. but came to a peak in Baghdad in the ninth century when Abu Yusuf Yaqub ibn-Ishaq al-Kindi (c.800-866) was head of the city’s medical school. Between 819 and 825, many books, especially medical texts, were taken from Constantinople to Baghdad, which meant that Islam had complete (and accurate) versions of original texts (including Theophrastus), already lost to the West. The delegation sent by Abbasid Caliph al-Ma’mun to Constantinople reported that the Byzantine Emperor had absolutely no knowledge of or interest in the fate of the ancient manuscripts; he did not even know where they were kept. But a scholarly monk did, and, perhaps feeling that they were likely to have a more secure future in Baghdad than Constantinople, revealed their hiding place. In AD 832, the Caliph set up a library and meeting place for scholars in Baghdad called the Bayt al-Hikma, the House of Wisdom, where the scholar-physician Hunayn ibn Ishak was head of a department wholly devoted to collating and translating foreign texts.

So, around 854, the first Arabic version of Dioscorides was produced by one of Hunayn’s translators, Stephanos, a Christian living in Baghdad. Stephanos translated as many Greek plant names as he could but when he didn’t know them, simply turned the Greek characters into Arabic ones, saying ‘God will raise up someone who might translate them.’ Stephanos’s translation from Greek to Arabic was widely circulated in Arabic countries until 948. Hunayn himself, an Arab Christian whose father was a pharmacist, also made translations from Greek into Arabic. He was equally fluent in Arabic and Syriac and before settling in Baghdad had spent two years travelling, perfecting his Greek and collecting books. Writing in 987, the Cordoban physician, Ibn Djuldjul. said that without Hunayn the Greek Dioscorides texts would never have reached the Arabs in Baghdad. Of the dozen or so illustrated medieval manuscripts that still exist of the Arabic version of Dioscorides, five use the words of Hunayn’s and Stephanos’s translation, picked over in the House of Wisdom in Baghdad.

In 948, the Byzantine Emperor Romanos II3 sent the Caliph of Cordoba, ‘Abd al-Rahman III (912-961), a present: a Greek manuscript of Dioscorides, superbly illustrated with Byzantine pictures. In his letter to the Caliph, Romanos said that the book, though itself a great treasure, could only be useful if the Greek was translated into Arabic by someone who knew about plants and the medicines made from them. By that stage, none of the Christians of Cordoba4 could read Ancient Greek, so for three years, the beautiful book lay in the Caliph’s library, unread. Then the Caliph asked Romanos if he could provide an interpreter. A Byzantine monk, Nicolas, was sent to Spain to join the team of scholars assembled in Cordoba. With the help of a Jewish doctor, Hasday b. Shaprut, and a Sicilian who spoke Greek and knew about medicinal plants, Nicolas gathered in another bunch of Dioscoridean plants, correlating them, not always successfully, with the flowers and shrubs that grew in Moorish Spain.5

Plate 25: An Arabian pharmacy from a manuscript made in Baghdad AD 1224

Despite the magnificent cross-culturalism of Arab scholarship (and in terms of the body of knowledge I’m interested in, the Arabs are the only people that matter at this time in the Western world), the central problem remained. It was easier to translate a text about a plant than it was to understand what the plant itself might be. Every country, every region of every country, had a different common name for the plants that they used for magic and medicine. Folio 98r of Juliana’s book shows a plant with dramatic arrow-shaped leaves, the plant we know as wild arum. Its official name is Arum maculatum, a name - thanks to the International Code of Nomenclature - now recognised in Europe as easily as in America, Japan, Australia or India. But when Dioscorides first wrote about this plant6 it may have been called ‘aron’, ‘aris’, ‘eparis’, ‘ephialton’, ‘kynozolon’, ‘onokephalon’, ‘parnopogonon’ or ‘phoinikeon’. If you were Egyptian, you’d have called it ‘ebron’; the Romans knew it as ‘beta leporina’, the Etruscans as ‘gigarum’, the Daker as ‘kurionnekum’, the North Africans as ‘ateirnochlam’, the Syrians as lupha’. If you could not be absolutely sure that this Greek plant was that Spanish (or Italian, or French, or Czech, or Polish or German or English) plant, none of the directions for preparing it or using it to quell fevers, heal wounds, knit bones, ward off monsters, was of the slightest use. A good proportion of those plants did not grow any further west than Greece, the limit of their natural habitat. Conversely, many of Dioscorides’s examples could also be found growing in countries further east than Greece. So Arabic scholars, though they struggled to equate the native flora of southern Spain with Dioscorides’s Eastern Mediterranean plants, did not have to struggle quite so frantically as those who emerged later in northern Europe.

Plate 26: ‘Dracontea’ (our dragon arum, Dracunculus vulgaris) in a manuscript made in the second half of the sixth century. The artist has shown the plant in berry rather than with its spooky dark spathe and has captured with great exactness the semi-circular arc of the leaflets that make up each leaf

The way that Dioscorides chose to describe plants also increased the difficulties. Like Theophrastus, Dioscorides often used analogy: this plant was like that plant but with bigger leaves, smaller flowers. While Theophrastus used a limited number of exemplars as his ‘standards’ - bay, laurel, pear - Dioscorides used many more. The probability of error was compounded. If you could not correctly translate the name of the standard plant used as a basis for comparison, you were even more unlikely to identify correctly the plant to which it was being likened. The body of plant knowledge embedded in the translations so carefully made from Greek into Arabic and Syriac by Hunayn and Stephanos remained tantalisingly obscure.

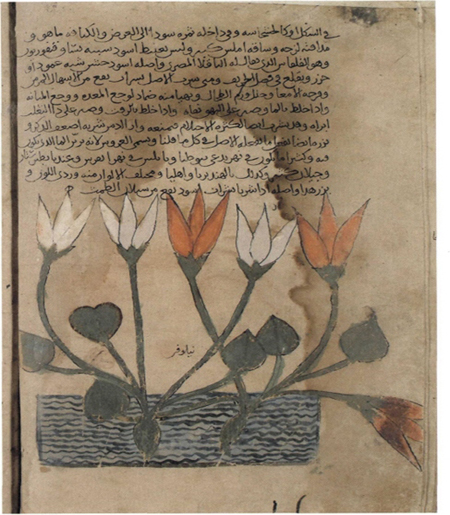

From the seventh century onwards, Arab conquests had fostered a revival of scientific learning throughout Islam, which contrasted vividly with the general stagnation in Christian Europe. Arabs controlled the main trade routes; prosperity created room for learning. By 976, the university at Cordoba, enlarged and endowed by Al-Hakim, was the best in Europe, the best in the whole of the Islamic Empire. In Baghdad the building of ‘Adud ad-Dawla’s teaching hospital, the al-Bimaristan al-’Adudi, was finished by 978 and the two dozen doctors who worked there set up a medical faculty, the first in the world. Islamic rulers supported scholarship and, at this time at least, showed an enlightened tolerance of other creeds, which compared rather favourably with the heresy-hunters of Christendom. ‘Read in the name of Allah,’ said the Koran. That was interpreted as a call to knowledge as well as a call to prayer. Study was a form of worship, and provided that scholarship could be shown to benefit humanity, few restraints were placed upon it. The Arabs excelled in the exact sciences - things that could be measured, research that was empirical rather than theoretical. Through the pursuit of knowledge lay salvation. Hunayn’s work was gradually revised and refined, culminating in the eleventh century in a text written in neat naskhi script on 228 paper pages, the oldest surviving Arabic herbal in the world.7 More than 600 illustrations decorate the pages, painted mainly in discreet shades of green, brown, orange and red, with much rarer touches of blue and yellow.8 The plants are those familiar to Dioscorides: rose, water lily, balsam (shown with two dramatic daggers plunged into the trunk to open up the supply of sap), orchids, the forked rooted mandrake. They are neat, but fairly crude drawings. You can recognise them, but only if you already know the plant. The water lily (five of them actually, three white, two red, elegantly interwined; see plate 27) is shown rising from a blue rippled sheet of water. Economically, the rose shows a selection of different blooms - red, white and a dark-rimmed pink - all flowering on the same bush. But you would be hard pressed to identify an orchid in the field from the sketchy, two-dimensional image on folio 32. The image of sap being bled from the balsam tree does not re-appear until the Tractatus de herbis made in the early fourteenth century, by which time there had been an important shift in the type of images being made. Instead of copying, almost superstitiously, the images carried down from antiquity (as if by changing them you might diminish the effect of their magical properties), artists began to draw plants as if they had them there in front of their eyes. Perhaps they did. However, it was the knowledge contained in Dioscorides that was further diffused by later Arab scholars such as Abu All al-Husayn b. ‘Abd Allah b. Sina (980-1037). Avicenna, as he was known in Western Europe, was born at Afshana near Bukhara and became personal physician to many rulers in the East, travelling over huge areas. His Qanun, translated into Latin by Gerard of Cremona in the twelfth century, remained a standard medical textbook for the next 500 years. It was a huge medical encyclopaedia, with details of 650 plants used in recipes for preparing 758 different medicines. Later, the celebrated Baghdad physician, ‘Abd al Latif (1160-1231) travelled throughout the East specifically to meet the greatest scholars of his generation. He taught both philosophy and medicine at Damascus and Cairo. That versatility, that curiosity was typical of this age of Arab scholars.

Plate 27: Red and white water lilies, entwined on the page of a manuscript made in northern Islam AD 1083

Though ideas travelled, became widely dispersed and understood, plant names did not. The Arab scholars, doctors and pharmacists intent on recapturing and preserving the plant knowledge of that Greek army doctor of the first century AD, relied to a great extent for their ingredients on herb-gatherers who only needed to recognise particular ‘simples’ which they knew to be in demand for particular prescriptions. It was not their business to be able to name that herb in any other language but their own. Though this conundrum remained, and was only slowly unpicked, Dioscorides’s treatise remained a prime source for Arab authors. Arab writers preferred to sort and order the material they gathered in the alphabetical order Dioscorides deplored; although, as a source, they treated him with great deference, reverence even, they did not agree that Dioscorides’s own way of arranging his material was the most practical one. And gradually, under the influence of these Arab scholars, Persian, Indian, and Arab plants completely unknown to Dioscorides were brought into the pharmacopoeia.

Though Islam encouraged scientific study - great progress was made in both medicine and agriculture - the making of realistic images was forbidden. Books on plants were beautifully illustrated, but the illustrations are stylised, flattened, almost as though they have been prepared as motifs for wallpaper or fabric (see plate 28). In the Süleymaniye Mosque Library at Ayasofia in Istanbul is an extravagantly illustrated Arabian version of Dioscorides.9 Using the original translation made by Hunayn’s assistant Stephanos, it was created in 1224, probably in Baghdad, then under the enlightened patronage of the Caliph Al-Nasir. Under his rule, Arab culture in the city reached a zenith, crushed and fractured only thirty-four years later when it was conquered by Mongol invaders. But even this manuscript, produced when Arab scholarship was at its peak, provides pictures of plants that are as fanciful as any in Edward Lear’s Nonsense Botany. Momentarily, the picture on folio 21 intrigues me (see plate 29). Shown alongside the central image (supposedly representing the plant the Arabs called bantafullun - our cinquefoil) are two details, as schematic as the central portrait. To the left of the main image is a shape like a cupped flower with seven small bobble-headed stems sticking out of it. On the right is a similar image that at first looks like a stylised bloom (three pointed petals), with the same bobbly lollipops sticking up from it. Stamens, I think. This man is actually trying to show stamens. Someone has finally grasped what a vital role they play in the life of a flowering plant. He’s giving us a detail, a close-up, to draw our attention to them. This is a breakthrough. And then I get out my magnifying glass and the theory crumbles almost as soon as it is born. Enlarged, the bobbles I’ve interpreted as stamens turn into miniature red and blue flowers, each with four petals. We are still hundreds of years away from any knowledge of the stamens and ovaries which will eventually play such a seminal part in the final naming of names.

Plate 28: A vine, springing from a curiously bulbous root, from a manuscript made in Baghdad AD 1224

The civilised, intellectually advanced Arab scholars of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries developed and elaborated the study of medicine far beyond the point where their Greek mentors had left it. They travelled widely, they drew on their own observations as Theophrastus had done, they organised expeditions specifically to look at and identify plants (in the early thirteenth century, the Muslim scholar Ibn al-Suri went plant-hunting in the Lebanon; it was a long time before any European botanist set out on a similar mission). But though they criticised, corrected, and added to the ancient Dioscorides text, they never abandoned it, never developed an entirely new cycle of treatises fuelled entirely from their own wisdom and experience. Why? This is what I wonder, as I sit in the poundingly silent rare book room at the University Library, Cambridge, looking at a fine Arab manuscript, probably made in the sixteenth century.10 The collection of plant drawings, brought to England from Smyrna in 1682, is now bound in a fat book, covered with heavy, dark, stamped leather. I want to sniff the leather like a dog (but I daren’t - the invigilator on his raised dais is a daunting figure) to catch a whiff of the manuscript’s past life. Who created it? Who owned it? Where has it travelled? Each of the 372 folios shows a single plant: sempervivum, artemisia, camomile, pimpernel, many beautiful umbellifers, elder, cranesbills, a turnip. An elegantly drawn teasel shows the prickly stems and the big boat-shaped bracts from which the flowering stems emerge, the whole coloured in a dull olive green overpainted with ochre-yellow highlights. There’s horsetail, iris, madonna lily, cyclamen, euphorbia (labelled with its old Greek name - ‘tithymalos’), and lesser celandine with distinctive long seed pods. At the back is a whimsical image of coral, shown growing in two horns out of the head of a Neptune figure, who sits on the seabed with fishes swimming around him and a serpent coiled uncomfortably in his lap.

Plate 29: ‘Bantafullun’ (supposedly our cinquefoil, Potentilla reptansj from a manuscript made in Baghdad AD 1224

Occasionally, on the reverse of one of the pages is a block of Arabic text, but this is chiefly a picture book. On the top right-hand corner of each page is a gathering of different names for the plant shown below. The University Library’s Handlist of Muhammadan MSS. (Cambridge, 1900) notes that these inscriptions are in Hebrew, Greek, Arabic and in some cases Turkish. Later research suggests that the Hebrew is written in a sixteenth-century Sephardi hand. Although the handlist doesn’t say so, the manuscript at some stage must also have belonged to an Italian, who added his own synonyms ‘geranio picolo’, ‘regolizi’, ‘eleboro’. I’m looking at the crazed tunnellings that bookworms have made across the pages, remembering that pit, dug before Christ was born, where Theophrastus’s great and original work on plants was buried and nearly perished. The pictures in the Cambridge manuscript are familiar, for the pages have been copied from Juliana’s book. Here is her absinth, though the plumes of red berries, so elegant in the original Greek manuscript, are lumpier here, not drawn out so gracefully, and the foliage is not so airy. Here is her asphodel, though the Cambridge manuscript does not show the turn of the leaf so well, nor is the flower head so well placed and balanced. Dioscorides first wrote about absinth in the second book of his De materia medica. Five hundred years later, he was the main source for the material in Juliana’s book. Another thousand years passes before this manuscript is made. Why, I’m wondering, were men still gazing at images of plants first made in the sixth century, still struggling to correlate names, still juggling synonyms? Why didn’t those clever Arabs push the story on further? Why didn’t they abandon the Greek script and write one of their own, more closely involving the cast of their own plant characters? Perhaps the gradual, but constant retailoring of Dioscorides was a sufficient shift in perspective for them. Perhaps, given their deep interest in medicine, they were content to extend the practical applications of the ancient text by continuing to tease out the likely identities of Dioscorides’s plants. Nowhere did they show any interest in engaging in the debate started by Theophrastus. Where are the relationships between these plants? What are the similarities, the differences between them? Where could the key be found to unlock the gate, to reveal why things were as they were, to see for the first time plants not dotted randomly around the pages of a herbal, subservient to the needs of medicine, but arranged according to a huge, beautiful and orderly system, answerable only to its own internal logic? But a mind, however highly refined, can only move to the unknown from the known. Theophrastus had asked the questions. The answers could emerge only when a great deal more was known about the plants themselves. Arranging a system remained the key difficulty. And there, Dioscorides did not help. He was more 104 interested in the medicinal possibilities of a plant than in the plant itself. So plants remained yoked to a drug list, and weren’t examined in a wider perspective.

Compared, though, to the stagnation in Europe, the burst of intellectual activity in Western Islam between the tenth and the thirteenth centuries is a miracle. Christianity had not had a liberating effect on the medieval mind in Europe. St Augustine taught that knowledge (which included, of course, all the sciences) was the reflection of the divine mind in human intelligence. It encouraged a kind of passivity. Illumination, clarification, could only be brought about by divine authority, either direct or interpreted by the intermediary of the church. Nature was ‘an empty vessel’ as Charles Raven calls it,11 a vacuum which the church filled with its own ideas. It did not foster or encourage individual observation and experiment. In the Middle Ages in Europe, interpreting the natural world was not so much a matter of teasing out the truth, as littering it with superstition, signs and portents. When the Arabs had completely assimilated all the knowledge that Western texts had to teach them, they re-exported that knowledge back into Europe. Through Arab infiltration, European scholars became acquainted again with the roots of their own culture. And learned a great deal else which had a profound effect on the way they subsequently viewed the world around them.

As slowly as Islam itself had assimilated the knowledge of the ancient Greeks, the fruits of Arab scholarship percolated to the West, often through Jewish intermediaries. They were scholarly, able to communicate in Greek and Arabic as well as Hebrew, multicultural before the word was even invented, men such as Sabbatai ben Abraham ben Joel (913-82), better known as Donnolo. He was a Jew of Otranto; when he was only twelve, he and his family were captured by Saracen raiders and taken to Palermo. By the time the family was ransomed by relatives in Italy, ben Joel was fluent in Arabic, which he had learned from his Saracen captors. He studied medicine and practised at Rossano in southern Italy. Like Constantine the African, who came after him, he claimed in his Book of Creation (c.946) to have studied ‘the sciences of the Greeks, Arabs, Babylonians and Indians’. He travelled all over Italy in search of fresh knowledge, spreading Arabic erudition as he went. Constantine the African (c. 1020-1087) was a native of Carthage, an Arabic-speaking Muslim who had travelled for many years in India and Persia. About 1065, he came via Sicily to Salerno, on the south-west coast of Italy. There, he learned both Latin and Greek, entered the monastery at Montecassino and spent the rest of his life translating Greek and Arabic works on medicine and plants into Latin. Single-handedly, he drew attention to this Greek/Arab body of knowledge a hundred years before translations began en masse.

For the most part, European scholars had to depend on these intermediaries to bring them the fruits of Arab scholarship. Arabic was too impenetrable a language, even for the great polymath Roger Bacon to decipher. He had no problems in teaching himself Greek and Hebrew but the only way to learn Arabic was to live in a country where the language was spoken. A few outstanding scholars such as Adelard of Bath (c.1080-1145) and Gerard of Cremona (1114-87) went to Spain and prepared their own translations of Arabic treatises - when Western science first began to draw from Islam, Spain was an important point of contact. After 1085, when El Cid stormed Toledo with Alphonso VI of Leon, the city became an important meeting point for East and West. I see the body of knowledge I’m interested in swirling across continents, as if on a vast map of the world displayed in a Second World War operations room. First, the action is in Byzantium, then Edessa, then Djundishapur, then Baghdad. When the first medical school of medieval Europe is established in 985 at Salerno by four doctors - a Greek, a Jew, a Saracen and a local Salerno man - that becomes the focus of intellectual activity. I don’t want my plants still to be yoked to the medical men, but without them, I’ve got nothing. In this whole vast period from Dioscorides to the Middle Ages, nobody seems to be looking at plants with a dispassionate eye. Medicine is skewing the plot. There is so much more out there that nobody is drawing or describing, because they yield no medicine, no food, no magic. Dioscorides is still regarded as the master, but of the 4,300 wild plants that grow naturally in Greece, he mentions only a fraction.

Plate 30: A bird and a grasshopper investigating the leaves of a plant which may be Rumex aquaticus. The artist has clearly shown how the plant propagates itself, with ‘pups’ growing from the rootstock

So I have to go to that medical school at Salerno, closely connected with the Benedictine monastery at Monte Cassino, where the best texts about Greek plants and medicine are available. Why was the school set up at Salerno? For the same reason that, in the eighteenth century, physicians flocked to Bath. Salerno, on the coast south of Naples, was where wealthy people went to take the waters. In the seventh century BC, just forty kilometres to the south on the fertile coastal plain, the Greeks had founded the flourishing city of Poseidonia, later taken over by the Romans who called it Paestum. It was a part of Italy where the former Greek colonies still preserved Greek traditions. It was close to Sicily where, at Palermo, the island’s Saracen conquerors had set up a medical school a hundred years earlier. Gradually, the Salerno medical school established a reputation for producing the most reliable, the most practical treatises of the Middle Ages. Much of that was due to the influence of the Arabs and their knowledge. Sooner than any other seat of learning in Europe, the medical school at Salerno absorbed what Islam had to teach. But in 1224, Emperor Frederick II endowed a university at Naples which drew many of the best people away from the old school. By the time Napoleon closed the Salerno school down in 1811, it had become a place of bogus degrees.

Plate 31: An unlikely looking bramble (Rubus fruticosus) from a manuscript made in Baghdad AD 1224. The rootstock has been shown as a kind of bulb and a weird growth like a wolf’s tail rises from the centre of the plant